Abstract

Background

Gastrinomas are one of the neuroendocrine tumors with potential distant metastasis. Most gastrinomas are originated from pancreas and duodenum, but those of gastric origin have been much less reported. The aim of the study is to compare gastrinomas of gastric and non-gastric origins.

Methods

Four hundred twenty-four patients with neuroendocrine tumor by histological proof in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou branch in the past 10 years were included. A total of 109 (25.7 %) cases were identified of upper gastrointestinal origins, of which 20 (18.3 %) were proven gastrinomas. The clinical characteristics were collected and analyzed retrospectively.

Results

In our study, 21 tumors of the 20 cases were identified by pathologic proof, 11 (55 %) had resection or endoscopic mucosa resection, 9 of gastric origins, 9 of duodenal origins, 2 of pancreatic origins, and 1 of hepatic origins. One case had multiple lesions. Patients with gastric gastrinomas had older age, higher levels of gastrin, seemingly smaller tumor size (p = 0.024, 0.030, and 0.065, respectively), and usually lower grade in differentiation (p = 0.035). Though gastric gastrinomas had a high recurrent rate (80 %), the lymph node and liver involvement was less common. Gastrinomas with liver involvement/metastasis had a high mortality rate where 80 % died of liver dysfunction.

Conclusions

Gastrinomas originating from stomach had higher gastrin level and lower tumor grading and presented at older age. The long-term outcome was probably better than non-gastric origin because of lower grading and less lymph node and liver involvement.

Keywords: Gastrinoma, Lymph node metastasis, Liver metastasis, Prognosis

Background

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are differentiated from epithelial cells of gastrointestinal tract or pancreas. Even though less common than other gastrointestinal malignancy, the incidence of neuroendocrine tumors has significantly increased in the last three decades because of the advance in diagnosis [1–8]. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors can secrete different kinds of neuropeptides or hormones, leading to a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from completely asymptomatic to patient discomfort. The neuroendocrine tumors can be grouped into functional or nonfunctional by clinical presentations [2]. Gastrinomas, one of the common functional neuroendocrine tumors, can over-synthesize gastrin and are usually presented as recurrent peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, diarrhea, or abdominal pain and are referred to as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) [9–13].

More than 80 % of gastrinomas are found in the gastrinoma triangle, an important anatomic mark for localization [14–16]. Advances in imaging tools, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging with dynamic phases, help identify the location of gastrinomas. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy have provided better sensitivity for subcentimeter gastrinomas [10]. But the incidence of gastric gastrinomas was increased in the past 50 years [2]. Gastrinomas in the pancreas have higher malignancy rate as compared to those in the duodenum [17]. The therapeutic strategies for gastrinomas include surgical treatment, local endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), targeted therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and acid antisecretory medication [18]. Surgery and local resection, with an intent for curative treatment, still has more than 30 % of recurrence rate, where lymph nodes and livers are the most common metastatic sites for relapse (in 86 and 43 % of cases, respectively) [7, 14, 19–21]. Diffused liver tumor infiltration carries the worst survival rate, and multiple lymph node metastases are associated with rapid tumor relapse [18]. However, in one report, curative resection and regional lymph node dissection provided better prognosis [19].

In recent years, increasing incidence of subclinical gastric gastrinomas has been found by panendoscopic examination. Gastric NETs are divided into four groups [22]. Type 1 and type 2 are gastric gastrinomas, which cause hypergastrinemia and can be treated by local excision, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection or endoscopic polypectomy, but partial or total gastrectomy may be needed when recurrence occurs [23, 24]. Type 3 and 4 are rare and not associated with gastrin production. However, the difference of clinical pictures and outcomes among gastric, pancreaticoduodenal, and hepatic gastrinomas has not been well reviewed from the literature, except for a few studies of gastrinomas in eastern Asia [7, 23]. In this study, we performed a clinical cohort review of gastrinoma cases in a single institute, especially for these two different origins.

Methods

Patients

A retrospective cohort study from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2012 was approved by the Institutional Review Boards, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB 102-2975B). Four hundred twenty-four patients with pathologically proven neuroendocrine tumors from the Cancer Registry of Cancer Center, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou branch were checked of histology, and 109 (25.7 %) cases with tumors of upper gastrointestinal origins were selected. The diagnosis of gastrinomas was based on clinical symptoms as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, higher serum gastrin level, and pathology criteria [25, 26]. Of these, 20 patients (18.3 %) were enrolled, and the demographic data, peptic ulcer/GERD treatment, gastrin level, tumor size, tumor grading, and metastasis were recorded, in which 9 specimens were of gastric origin, 9 specimens of duodenal origin, 2 of pancreatic origins, and 1 of hepatic origin. One patient had multiple lesions. Most were sporadic gastrinomas, but two cases from the same family were MEN type 1. The treatment methods including resection, endoscopic mucosal resection, and adjuvant/salvage treatment were analyzed.

All patients had imaging studies, at diagnosis and follow-up, using endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients were divided into two groups according to their primary site of origin (gastric or non-gastric), and continuous and categorical data were analyzed by Student’s T test and chi-square methods. The overall survival was analyzed by log-rank test, and significant difference was defined as P value < 0.05. (IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0.)

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded resection specimens were sectioned to 4 μm in thickness and deparaffinized, rehydrated, and processed for antigen retrieval. The slides were further incubated with appropriate dilutions of the following antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, the slides were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated with a horse reddish peroxidase conjugated antibody polymer (Zymed) at room temperature for 10 min, and were then developed by treatment with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Roche) at room temperature for 10 min. The used monoclonal antibody for Immunohistochemistry (IHC) were against Ki-67 (1:1000, Dako) and chromogranin A (1:500, Dako). For gastrin staining we used polyclonal antibody against gastrin (LEICA biosystems) without antigen retrieval. Ki-67 staining and mitotic counts per 10 high power field were used for tumor grading [25]. In brief, more than 20 in mitotic index were classified as G3. Independent experienced pathologists blinded of patient characteristics and outcomes studied the results of immunohistochemical staining for diagnosis and classification [25].

Results

The details of 20 cases are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 47.2 years with equal gender distribution. The mean tumor size was 7.3 mm, and the mean gastrin level at diagnosis was 352.0 pg/ml. Seven cases (36.8 %) developed recurrence and most had metastasis to liver and lymph node. Four cases were lost for follow-up because of liver metastasis and dysfunction. The mean follow-up period was 73.2 months. The demographic data are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Personal characteristic data of twenty cases with gastrinoma

| Case no. | Age | Gender | Clinical presentation | Primary site | WHO grading | Gastrin (pg/ml) | Procedure | Tumor size (mm) | Outcome | F/u period (months) | LN meta | Liver meta | Other meta | Medical treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 51 | Male | GERD, Erythematous gastritis | Stomach | G1 | 641 | PES biopsy | 6.0 | Alive with regional tumor | 65.6 | Nil | Nil | Nil | H2 blocker |

| 02 | 52 | Male | Epigastralgia, Erythematous gastritis, Diarrhea | Stomach | G1 | 924 | PES biopsy | 2.0 | Alive with regional tumor | 111.5 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| 03 | 50 | Male | Epigastralgia | Stomach | G1 | 568 | EMR | 4.0 | Free | 127.8 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| 04 | 75 | Female | Epigastralgia, Erythematous gastritis | Stomach | G1 | 993 | PES biopsy | N/A | Alive with regional tumor | 27.6 | N/D | N/D | N/D | Nil |

| 05 | 74 | Female | GERD, Gastric erosions | Stomach | G1 | 2878 | PES biopsy | 6.0 | Alive with regional tumor | 32.6 | N/D | N/D | N/D | Nil |

| 06 | 48 | Female | Z-E syndrome, Diarrhea | Stomach | G1 | 671 | Total gastrectomy | N/A | Liver recurrent | 77.2 | Nil | 7 mm, S5/8 | Nil | Nil |

| 07 | 58 | Female | UGI bleeding | Stomach | G1 | 1690 | EMR | 4.8 | Recurrent, site unknown | 80.4 | Nil | Nil | Nil | H2 blocker |

| 08 | 56 | Female | GERD, Erythematous gastritis | Stomach | G1 | 1770 | EMR | 8.0 | Regional recurrent | 94.8 | Nil | Nil | Nil | H2 blocker |

| 09 | 43 | Female | Duodenal ulcer, GERD grade A | Stomach | G1 | 1817 | EMR | 5.2 | Regional recurrent | 112.3 | Nil | Nil | Nil | H2 blocker |

| 10 | 12 | Male | Diarrhea, Esophageal ulcers, Gastric ulcer | Duodenum | G3 | 8219 | Liver biopsy PES biopsy | N/A | Expired—liver failure | 9.44 | Yesa | Yes | Bone Lung | Octreotide LAR PPI Evolimus CTc |

| 11 | 35 | Male | Repeat peptic ulcer, Epigastralgia | Duodenum | G1 | 1179 | Antrectomy + Duodenectomy with lymph node resection | 15.0 | Alive with lymph node metastasis | 26.2 | Yes, Group 12 | Nil | Nil | Octreotide LAR PPI |

| 12 | 64 | Male | Chronic gastritis | Duodenum | G1 | 75 | EMR | 5.0 | Free | 42.9 | N/D | N/D | N/D | Nil |

| 13 | 32 | Male | GERD grade A Superficial gastritis, Duodenal erosions | Duodenum | G1 | 58 | PES biopsye | 5.0 | Alive with disease (MEN-1) | 48.2 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| 14 | 34 | Male | Epigastralgia | Duodenum and pancreas | G1 | 35 | Subtotal gastrectomy + distal pancreatectomyf | 6.0 | Alive with disease (MEN-1) | 53 | Yesb | Nil | Nil | Octreotide LAR Evolimus PPI |

| 15 | 39 | Male | Gastric ulcers | Duodenum | NA | 105 | PES biopsy | 8.0 | Alive with regional tumor | 127.3 | N/D | Nil | N/D | PPI |

| 16 | 25 | Male | Diarrhea | Pancreas | G2 | 359 | Liver biopsy | N/A | Expired | 64 | Yes | Yes | Nil | Octreotide LAR PPI Sunitinib |

| 17 | 55 | Female | UGI bleeding, Peptic ulcer | Duodenum | G2 | nil | Liver biopsy | N/A | Expired | 27.1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | PPI |

| 18 | 72 | Female | Diarrhea, Abdominal pain | Duodenum | NA | 1341 | EMR | 15.0 | Free | 80.3 | Nil | Nil | Nil | PPI |

| 19 | 36 | Female | GERD | Duodenum and lymph node | G1 | 217 | LN excision EMR | 60.0 | Free | 102.1 | Yes | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| 20 | 33 | Female | Peptic ulcer, UGI bleeding | Liver | G3 | 1570 | Hepatectomy | 150.0 | Expired—liver failure | 205.8 | Nil | Liver origin | Bone PC | Octreotide LAR HAICd PPI |

N/A not available, ND not done, PES panendoscopy, EMR endoscopic mucosal resection, LAR long-acting repeatable, PPI proton pump inhibitor, CT chemotherapy, HAIC hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, GERD Gastroesophageal reflux disease, PC Peritoneal carcinomatosis

aMediastinal and Porta hepatis lymph nodes

bMediastinal lymph nodes

cChemotherapy with VP-16/Etoposide + Cisplatin/CDDP

dHAIC with 5-FU + Cisplatin

eSpecimen positive of gastrin and somatostatin

fPositive of gastrin, glucagon, and insulin

Table 2.

Gastric origin compared with non-gastrin origin

| All | Gastric | Non-gastric | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 20 | n = 9 (45 %) | n = 11 (55 %) | ||

| Age (years) | 47.2 ± 16.8 | 56.3 ± 11.2 | 39.7 ± 17.4 | 0.024 |

| Gender (M/F) | 10/10 | 3/6 | 7/4 | 0.370 |

| Size (mm) | 7.3 ± 4.3 | 5.1 ± 1.9 | 9.1 ± 5.0 | 0.065 |

| Grading by WHO G1/G2/G3a | 14/2/2 (78 %/11 %/11 %) | 9/0/0 | 5/2/2 | 0.035 |

| Gastrin level (pg/ml) | 352.0 ± 313.7 | 512.3 ± 323.3 | 207.7 ± 234.7 | 0.030 |

| Treatment (Biopsy/resection) | 9/11 (45 %/55 %) | 4/5 (44 %/56 %) | 5/6 (45 %/55 %) | 1.000 |

| Metastasisb | 7 (36.8 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 5 (45.5 %) | 0.080 |

| Recurrencec | 7 (63.6 %) | 4 (80 %) | 3 (50 %) | 0.348 |

| Death, disease specific | 4 (20 %) | 0 (0 %) | 4 (36.4 %) | 0.068 |

aTwo cases of biopsy were not suitable for histology grading

bOne case has no enough follow-up

c9 cases had biopsy and no treatment

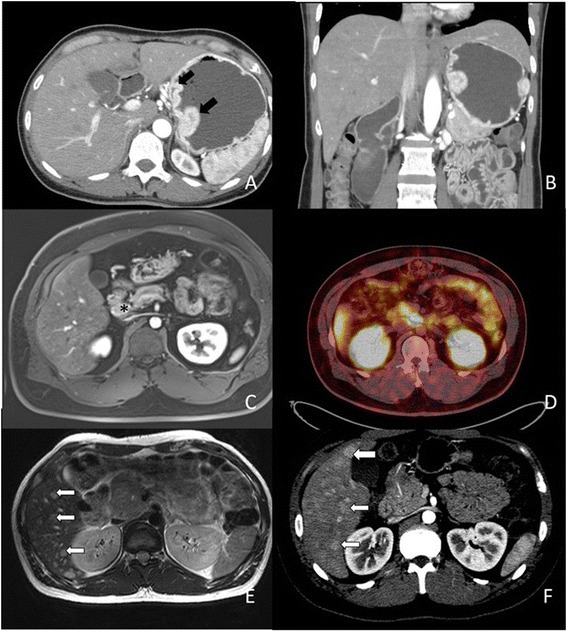

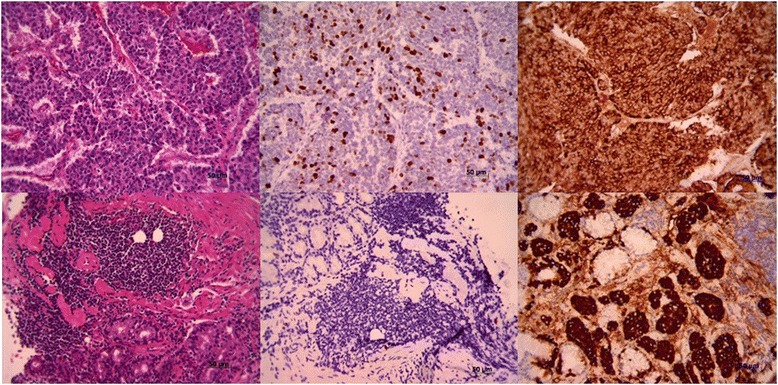

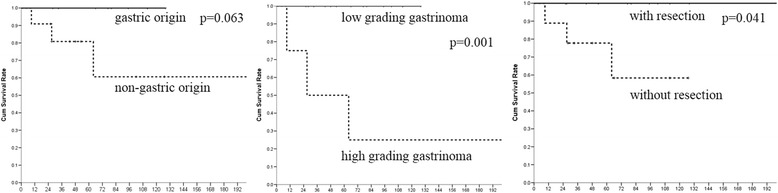

The CT imaging was shown in Fig. 1, with an emphasis on the presentation of lymph node metastasis. Compared with those of non-gastric origin, patients with gastric gastrinomas had significantly elder age (56.3 ± 11.2 vs. 39.7 ± 17.4, p = 0.024) and higher gastrin level (512.3 ± 323.3 vs. 207.7 ± 234.7 mg/ml, p = 0.030), however, smaller tumor size (7.3 mm vs. 5.1 mm, P = 0.065). Four gastrinomas of high or moderate tumor-grade (G2, 3) all had non-gastric origins (p = 0.035). The histology, Ki-67 staining, and chromogranin A staining are shown in Fig. 2. Overall survival rate was showed in Fig. 3. Patients with low grade gastrinoma and with resection treatment had better survival outcome. Besides, of those patients with tumor of gastric origin, although most received local treatment, seems to have less distant metastasis and better long-term survival; no statistically significant difference was found due to small case numbers.

Fig. 1.

Axial contrast enhanced CT scan of upper abdomen (arterial phase) shows a two enhanced polypoid mass (black arrow) at high gastric body along lesser curvature side. b Coronal multiplanar reformation image. (1) Axial dynamic fat-saturated T1-weighted image with gadolinium enhancement shows enlarged lymph node (*) at peripancreatic area (c). (2) Ga-68 DOTATOC-scan shows strong uptake at medial aspect of uncinate process of pancreas (d). (3) Infiltrative tumor at pancreatic head with diffuse liver metastases (white arrow) e Axial dynamic fat-saturated T2-weighted image with gadolinium enhancement. f Axial contrast CT scan in arterial phase

Fig. 2.

Histology and immunohistochemistry staining of gastrinomas. Upper panel represents high-grade non-gastric and lower panel is low-grade gastric gastrinoma. The image shows histology, Ki-67 staining, and chromogranin staining from left to right, (100× magnification)

Fig. 3.

The Kaplan-Meier overall survival rate between a gastric origin (solid line) and non-gastric origin (dotted line), b low and high grading gastrinoma (G1 vs. G2, G3 solid line vs. dotted line), and c with/without resection (solid line/dotted line). P = 0.063, 0.001, and 0.041, respectively. WHO grading was most important for prognosis, but gastric gastrinomas got better survival rate

Discussion

Most gastrinomas are well-differentiated endocrine tumors with benign or low-grade malignant behavior, whereas poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare (1–3 %) [25]. Early reports that have shown pancreatic NETs are usually larger than 1 cm and have higher risks for liver metastases [14, 27]. However, gastrinomas originating from stomach have seldom been studied [17, 23, 24]. In this study, 20 cases were identified with pathology proof, in which 9 were of gastric and 9 were of duodenal origins. One case with more than 10 years of follow-up was identified to have lesions only in the liver, and primary liver gastrinoma was classified. Comparing with those of hepatic-pancreatic-biliary origins, gastric gastrinomas had significantly higher gastrin levels but smaller tumor size, lower ki-67 proliferation index, and more well-differentiated tumors (G1). The long-term outcome seems better in gastric origin group that no cases had lymph node involvement and only one had liver metastasis.

All nine cases of gastric origin showed higher gastrin level, whereas three cases of non-gastric origin had normal gastrin level (<100 ng/ml) from our study. Though gastric gastrinomas type I and II had better long-term outcome, the recurrence rate was higher up to 80 % in this series. Regional recurrence was common and proton pump inhibitors were not administered because they all had good quality of life. Regional recurrence was possibly related to multicentricity or inadequate resection [28]. Patients would not like to have another following treatment, as the report from Li, et al [23]. However, gastric gastrinomas could be treated with repeated resection in selected conditions [24].

Until now, unknown primary origins and distal metastasis are of the greatest concern. The incidence of subcentimeter gastric origins was higher than that of reported by others, suggesting that upper gastrointestinal studies should be considered when unknown origins were encountered [29]. Delayed identification of tumor origin occurred in one of our patients. She underwent retroperitoneal lymph node resection initially, and the primary duodenal origin was found when routine endoscopy was done during follow-up. Identifying the primary origin is still of great challenge. The outcome analysis studies revealed that patients with lymph node involvement distant metastases had poorer outcomes. Though the use of long-acting octreotide has been the clinical practice, the satisfying outcome is still not supported by stronger evidence [10, 30]. One case of liver origin reported years ago received repeated resection for her liver tumors. She did not survive with LAR treatments because of liver dysfunction. In our series, liver metastasis presented the worst outcome and four out of five cases had mortality at follow-up. As reported in some studies, aggressive LN dissection/resection strategy improved patient’s outcome, and it was also compatible with our findings [31].

One special case in this study is a MEN-1 patient with duodenal and pancreatic gastrinoma. The patient’s histology and special staining were reviewed, and the duodenal lesion and one of four pancreatic NETs were positive for gastrin stain. But MEN-1 patients who had pancreatic gastrinoma were extremely rare, and metastasis should be considered [32]. Because we have no further study for tumor genetic heterogeneity, this case was assumed as duodenal and pancreatic gastrinoma.

Conclusions

In summary, patients with gastric gastrinomas usually have older age, higher gastrin level, more subcentimeter tumor size, and significantly lower tumor grading. Endoscopic mucosal resection usually helps minimize the need for medication need, but local recurrence can be common. The probability of distant metastasis is low, and long-term outcome is better than those of duodenum, pancreas, and liver origins.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all our colleagues and authors in the Department of Cancer Center and Chang Gung University for their technical assistance. This study was supported by the Chang Gung Memorial Foundation (CMRPG3C0711-2).

Footnotes

Song-Fong Huang and I-Ming Kuo contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HSF and KIM contributed to data collection, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and was the primary writer of the manuscript. LCW, PKT, CTC, LCJ, and HTL contributed to the acquisition of data. YMC contributed to the design of the study, manuscript review, and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Song-Fong Huang, Email: b9102059@cgmh.org.tw.

I-Ming Kuo, Email: m7017@cgmh.org.tw.

Chao-Wei Lee, Email: alanchaoweilee@hotmail.com.

Kuang-Tse Pan, Email: pan0803@cgmh.org.tw.

Tse-Ching Chen, Email: ctc323@cgmh.org.tw.

Chun-Jung Lin, Email: ma1249@cgmh.org.tw.

Tsann-Long Hwang, Email: hwangtl@cgmh.org.tw.

Ming-Chin Yu, Email: mingchin2000@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Fraenkel M, Kim MK, Faggiano A, Valk GD. Epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26(6):691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC, Jensen RT, de Herder WW, Thakker RV, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(1):61–72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The Epidemiology of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Carbonero R, Capdevila J, Crespo-Herrero G, Diaz-Perez JA, Martinez Del Prado MP, Alonso Orduna V, et al. Incidence, patterns of care and prognostic factors for outcome of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): results from the National Cancer Registry of Spain (RGETNE) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(9):1794–803. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mocellin S, Nitti D. Gastrointestinal carcinoid: epidemiological and survival evidence from a large population-based study (n = 25 531) Ann Oncol. 2013;24(12):3040–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito T, Igarashi H, Nakamura K, Sasano H, Okusaka T, Takano K, et al. Epidemiological trends of pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in Japan: a nationwide survey analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(1):58–64. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0934-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraenkel M, Kim M, Faggiano A, de Herder WW, Valk GD. Incidence of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review of the literature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(3):R153–63. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, Abou-Saif A, Peghini P, Doppman JL, et al. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Clinical presentation in 261 patients. Medicine. 2000;79(6):379–411. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epelboym I, Mazeh H. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: classical considerations and current controversies. Oncologist. 2014;19(1):44–50. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Feigenbaum KM, Koviack PD, Bashir S, Ojeaburu JV, et al. Gastric secretion in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Correlation with clinical expression, tumor extent and role in diagnosis--a prospective NIH study of 235 patients and a review of 984 cases in the literature. Medicine. 2001;80(3):189–222. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine. 2004;83(1):43–83. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000112297.72510.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zollinger RM, Ellison EH. Primary peptic ulcerations of the jejunum associated with islet cell tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1955;142(4):709–23. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195510000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zogakis TG, Gibril F, Libutti SK, Norton JA, White DE, Jensen RT, et al. Management and outcome of patients with sporadic gastrinoma arising in the duodenum. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):42–8. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000074963.87688.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cisco RM, Norton JA. Surgery for gastrinoma. Adv Surg. 2007;41:165–76. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stabile BE, Morrow DJ, Passaro E., Jr The gastrinoma triangle: operative implications. Am J Surg. 1984;147(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Toole D, Delle Fave G, Jensen RT. Gastric and duodenal neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26(6):719–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krampitz GW, Norton JA. Current management of the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Adv Surg. 2013;47:59–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovinazzo F, Butturini G, Monsellato D, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Bassi C. Lymph nodes metastasis and recurrences justify an aggressive treatment of gastrinoma. Updates Surg. 2013;65(1):19–24. doi: 10.1007/s13304-013-0201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veenendaal LM, et al. Liver metastases of neuroendocrine tumours; early reduction of tumour load to improve life expectancy. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maire F, Sauvanet A, Couvelard A, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Lebtahi R, et al. Recurrence after surgical resection of gastrinoma: who, when, where and why? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(4):368–74. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328350f816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basuroy R, Srirajaskanthan R, Prachalias A, Quaglia A, Ramage JK. Review article: the investigation and management of gastric neuroendocrine tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(10):1071–84. doi: 10.1111/apt.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li QL, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Ma LL, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for foregut neuroendocrine tumors: an initial study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(40):5799–806. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crosby DA, Donohoe CL, Fitzgerald L, Muldoon C, Hayes B, O'Toole D, et al. Gastric neuroendocrine tumours. Dig Surg. 2012;29(4):331–48. doi: 10.1159/000342988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosman F, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise N. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyons: IARC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berna MJ, Hoffmann KM, Serrano J, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Serum gastrin in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: I. Prospective study of fasting serum gastrin in 309 patients from the National Institutes of Health and comparison with 2229 cases from the literature. Medicine. 2006;85(6):295–330. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000236956.74128.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber HC, Venzon DJ, Lin JT, Fishbein VA, Orbuch M, Strader DB, et al. Determinants of metastatic rate and survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective long-term study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(6):1637–49. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donow C, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Schroder S, Stamm B, Heitz PU, Kloppel G. Surgical pathology of gastrinoma. Site, size, multicentricity, association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and malignancy. Cancer. 1991;68(6):1329–34. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910915)68:6<1329::AID-CNCR2820680624>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(1):23–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shojamanesh H, Gibril F, Louie A, Ojeaburu JV, Bashir S, Abou-Saif A, et al. Prospective study of the antitumor efficacy of long-term octreotide treatment in patients with progressive metastatic gastrinoma. Cancer. 2002;94(2):331–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartsch DK, Waldmann J, Fendrich V, Boninsegna L, Lopez CL, Partelli S, et al. Impact of lymphadenectomy on survival after surgery for sporadic gastrinoma. Br J Surg. 2012;99(9):1234–40. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloppel G, Perren A, Heitz PU. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: the WHO classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:13–27. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]