Abstract

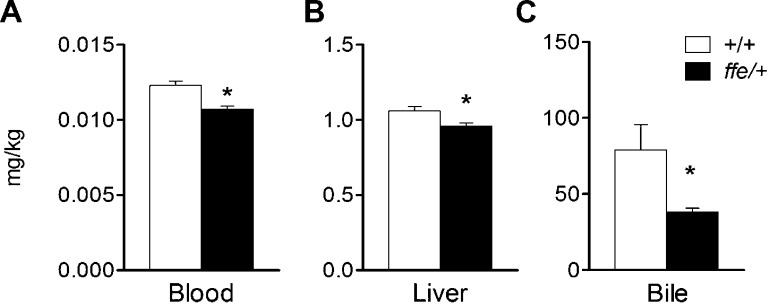

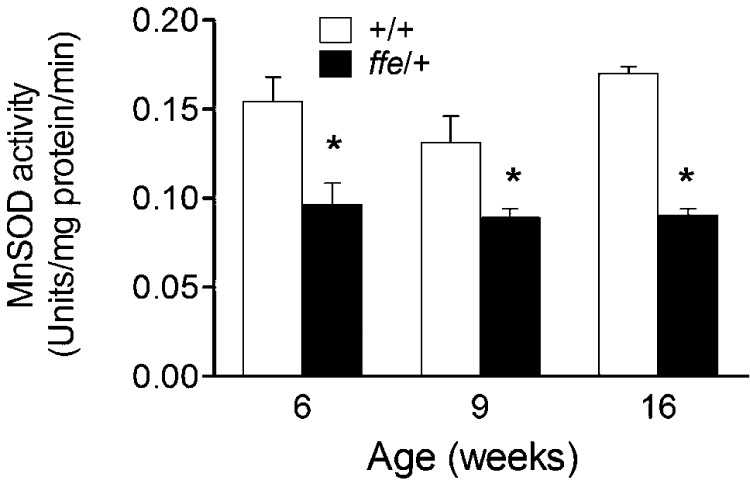

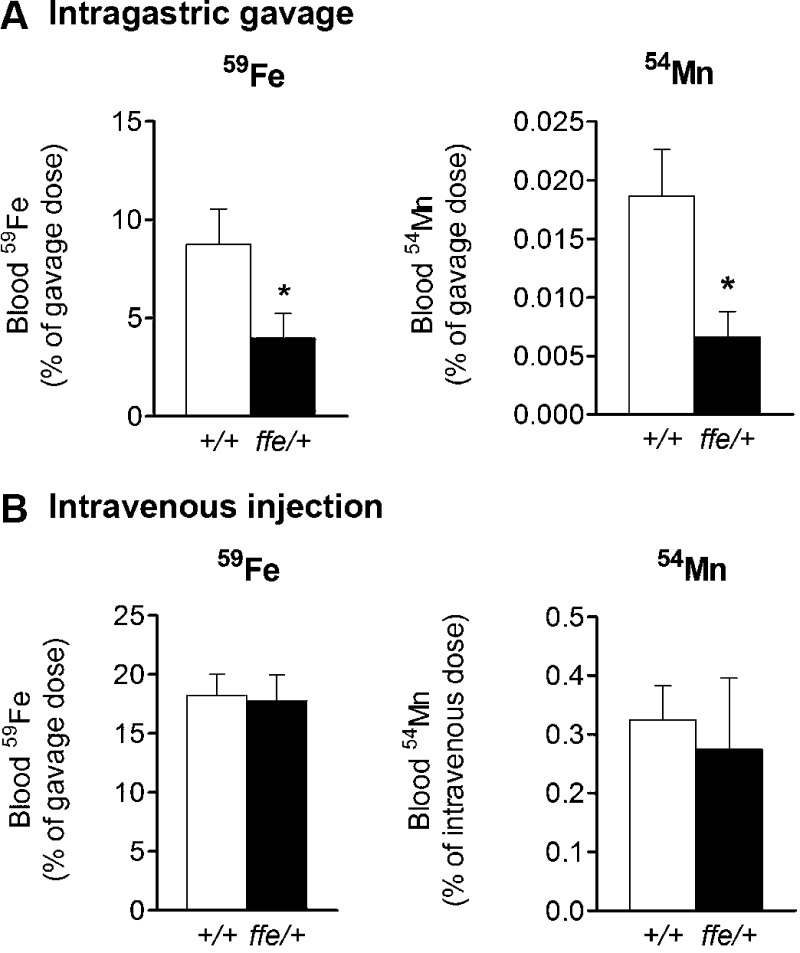

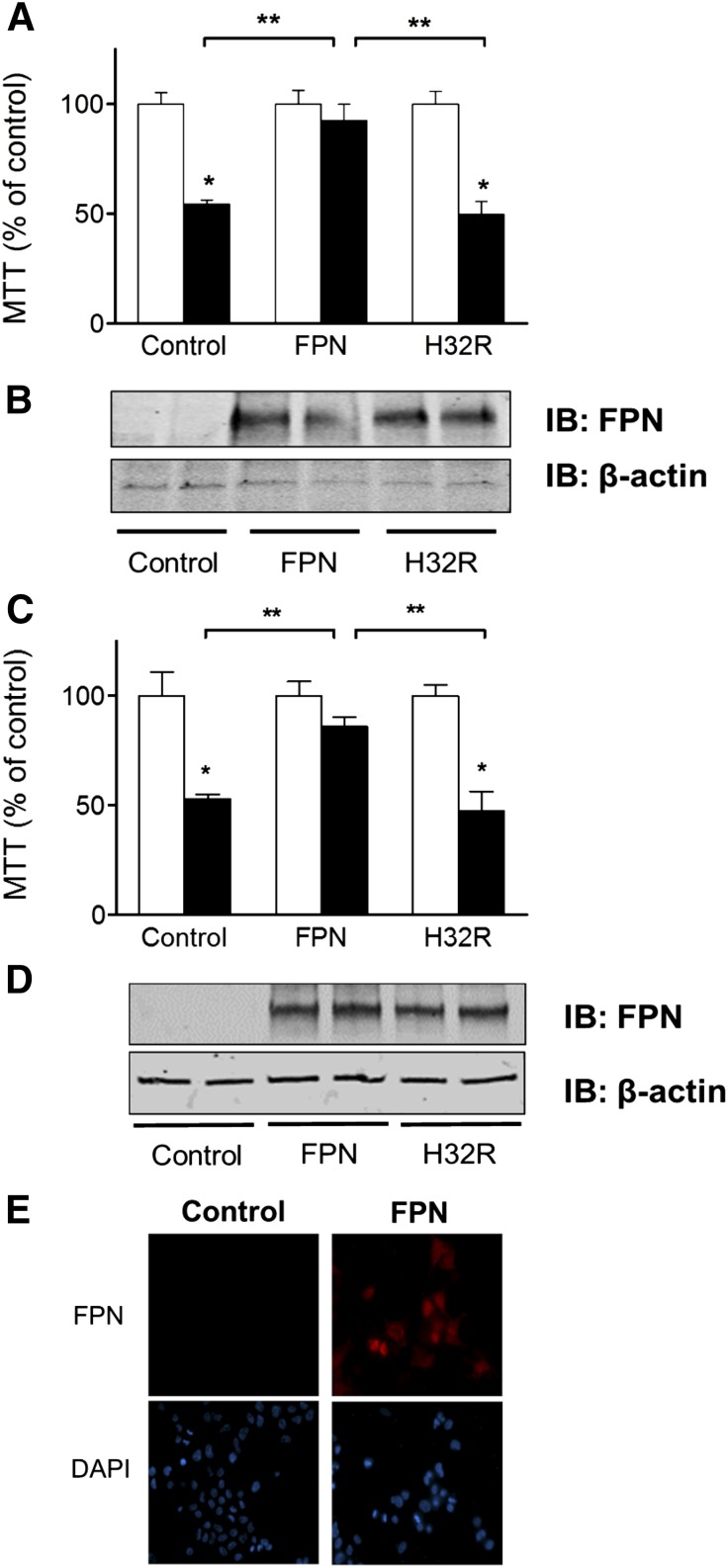

We examined the physiologic role of ferroportin (Fpn) in manganese (Mn) export using flatiron (ffe/+) mice, a genetic model of Fpn deficiency. Blood (0.0123 vs. 0.0107 mg/kg; P = 0.0003), hepatic (1.06 vs. 0.96 mg/kg; P = 0.0125), and bile Mn levels (79 vs. 38 mg/kg; P = 0.0204) were reduced in ffe/+ mice compared to +/+ controls. Erythrocyte Mn–superoxide dismutase was also reduced at 6 (0.154 vs. 0.096, P = 0.0101), 9 (0.131 vs. 0.089, P = 0.0162), and 16 weeks of age (0.170 vs. 0.090 units/mg protein/min; P < 0.0001). 54Mn uptake after intragastric gavage was markedly reduced in ffe/+ mice (0.0187 vs. 0.0066% dose; P = 0.0243), while clearance of injected isotope was similar in ffe/+ and +/+ mice. These values were compared to intestinal absorption of 59Fe, which was significantly reduced in ffe/+ mice (8.751 vs. 3.978% dose; P = 0.0458). The influence of the ffe mutation was examined in dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells and human embryonic HEK293T cells. While expression of wild-type Fpn reversed Mn-induced cytotoxicity, ffe mutant H32R failed to confer protection. These combined results demonstrate that Fpn plays a central role in Mn transport and that flatiron mice provide an excellent genetic model to explore the role of this exporter in Mn homeostasis.—Seo, Y. A., Wessling-Resnick, M. Ferroportin deficiency impairs manganese metabolism in flatiron mice.

Keywords: iron metabolism, hepcidin, manganese transport

Manganese (Mn) is an essential nutrient required for neurotransmitter synthesis and metabolism (1). It is critical for antioxidant functions because mitochondrial superoxide dismutase requires Mn as a cofactor (MnSOD) (2). Mn is also a cofactor for a number of enzymes involved in amino acid, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism, and it plays important roles in immune function, bone, and connective tissue growth (3).

Despite the importance for Mn in human health, Mn is toxic when accumulated at high levels, and chronic exposure impairs neurotransmitter systems (4) and neurobehavior (5–7). Excess Mn causes manganism, a Parkinsonlike neurologic disorder due to Mn accumulation in the brain (8, 9). High levels of Mn exposure are common in occupational settings of mining, welding, Mn ore processing, dry battery manufacture, and organochemical fungicide use (10, 11). Recent concerns about Mn exposure are raised from its use in the fuel additive methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (12, 13). In urban settings, multiple transition metals including Mn are found in particulate matter (14).

Mn homeostasis must be tightly controlled to guard against the neurotoxic effects of excess metal while providing sufficient nutrient for proper growth and development. For example, toxic effects of hypermanganesemia are seen in an inherited Mn overload syndrome associated with genetic defects in SLC30A10 (15, 16). Recent studies have shown that SLC30A10 is a cell surface-localized Mn efflux transporter that reduces cellular Mn levels and protects against Mn toxicity (17, 18). Other evidence points to close transport relationships between iron (Fe) and Mn (19). Mutations in divalent metal transporter-1 (DMT1), a known Fe importer, have been shown to disrupt Mn uptake from the diet (20) and through the olfactory pathway to the brain (21). However, the role of ferroportin (Fpn), the only known mammalian Fe exporter, in Mn efflux remains unknown. Fpn was first demonstrated as an Fe exporter in zebrafish embryos carrying Fpn1 mutations (22). Defects in this transporter were associated with the failure to move Fe from the yolk sac to embryo. Xenopus oocytes injected to express Fpn display increased Fe efflux (23), confirming its role in export. Similar studies suggest that oocytes expressing this transporter export more 54Mn than control oocytes (24); however, conflicting evidence has been reported in this system (25). In other studies, inducible expression of Fpn in HEK293T cells reduced Mn accumulation and toxicity (26). While these authors report the induction of Fpn protein by Mn exposure (26), other reports indicate treatment with Mn has no effect on gene expression (27). Thus, whether or not Fpn exports Mn and plays a role in the metabolism of this metal remain controversial.

Flatiron (ffe) mice provide a genetic model to assess the role for Fpn in Mn export. Fpn knockout mice are available, but homozygotes display embryonic lethality, and heterozygotes do not reproduce features of human Fe-loading disease caused by loss of Fpn function (28). Ffe mice heterozygous for a H32R missense mutation in Fpn are viable and show Fe loading in macrophages of reticuloendothelial system, with reduced hematocrit, high serum ferritin, and low transferrin saturation (29). These are known features of human ferroportin disease, a form of hereditary hemochromatosis (30). It has been shown that this phenotype arises because the Fpn mutant H32R acts as a dominant negative to mislocalize wild-type Fpn away from the cell surface (29). To resolve the outstanding questions about the role of Fpn in Mn export, we characterized Mn metabolism in flatiron mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). The protocol used for these studies (Animal Experimentation Protocol AEP#04545) was approved by the Harvard Medical Area Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animal care and procedures

Flatiron (ffe/+) mice were kindly provided by I. E. Zohn (University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, CO, USA). All mice used for these studies were on the 129S6/SvEvTac background. Weanling mice were fed a diet containing 50 mg Fe/kg and Mn 35 mg/kg (TD120518; Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Mice were killed under isoflurane inhalation (5%) to obtain serum and liver. Nonheme Fe concentrations in these tissues were spectrophotometrically determined. All experiments were carried out between 12 and 3 pm to avoid circadian effects on Fe metabolism.

To characterize gastrointestinal absorption of Fe and Mn, mice were withheld food for 4 hours, anesthetized with up to 2% vaporized isoflurane, and administered 59FeCl3 (200 mCi/kg body weight) or 54MnCl2 (200 mCi/kg body weight) by intragastric gavage using a 20 gauge 1.5-inch gavage needle. 59Fe was diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing ascorbic acid (10 mM) at 1.5 ml/kg immediately before administration; 54Mn was diluted in PBS. Mice were killed by isoflurane overdose 1 hour (59Fe) or 15 minutes (54Mn) after gavage to collect blood and dissect tissues. Radioactivity was quantified in a γ scintillation counter. The blood levels of 59Fe or 54Mn represent the amount absorbed from the gut as well as the amount cleared from the circulation. Similar cohorts of mice were intravenously injected with the same dose of 59Fe or 54Mn via the tail vein to control for clearance of the metals to the blood level.

Trace element analysis

Tissues from ffe/+ and +/+ mice were analyzed for Fe by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry or Mn by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Trace Element Analysis Laboratory, Department of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA). Intracellular levels of Mn and Fe were measured by ICP-MS (Trace Metals Laboratory, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA).

Mn superoxide dismutase assay

Erythrocyte MnSOD activity was determined using a Superoxide Dismutase Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Briefly, blood was collected via tail vein at 6, 9, and 16 weeks of age using an anticoagulant EDTA tube and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the top yellow plasma layer and white buffy layer (leukocytes) were discarded. The erythrocytes were lysed in 4 volumes of ice-cold water and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. MnSOD activity was determined by in the presence of 2 mM potassium cyanide to inhibit Cu/Zn-SOD, thus measuring the residual MnSOD activity.

Generation of plasmid DNA constructs

Fpn plasmid was generated as previously described (31). Ffe mutant (H32R) was constructed with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The site-directed mutation, orientation, and fidelity of the insert and incorporation of the epitope tag were confirmed by directed sequencing (Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, DNA Resource Core, Boston, MA, USA).

Cell culture and expression of Fpn and flatiron mutant

All culture media and supplements were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), except for heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, which was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Manganese chloride (MnCl2) and DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Human SH-SY5Y cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were plated overnight in antibiotic-free growth medium in 6-well plates for cell viability experiments. Cells were transiently transfected with 4 μg of empty vector, pSport-Fpn, or pSport-H32R in antibiotic-free Opti-Minimal Essential Medium using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s specifications for up to 24 hours before experiments. To confirm efficiency of transfection, SH-SY5Y were transiently transfected using 4 μg pEGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA), and the percentage of cells expressing green fluorescent protein was determined counting at least 100 cells by direct fluorescence microscopy. The transfection efficiency measured in these control experiments using Lipofectamine 2000 was 37%, consistent with the effective use of this reagent to study membrane-associated transporters and neurodegenerative disease in SH-SY5Y cells by other investigators (32–38). To further confirm functional expression of wild-type Fpn and the H32R mutant, transfection experiments in HEK293T cells were also carried out. Cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator, then transfected exactly as described above. Transfection efficiency was determined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Briefly, HEK293T cells were fixed for 10 minutes with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose in PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM MgCl2, then blocked and permeabilized for 1h in 0.1% Tween-20 with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.3 M glycine in PBS. Cells were then incubated for 30 minutes with rabbit anti-SLC40A1 (Fpn) (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in PBS including 1% BSA in PBS and then incubated for 30 minutes with Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated anti-rabbit (1:1000; Invitrogen) in 1% BSA. Cells were extensively washed, and nuclei were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen) for 5 minutes. Coverslips were mounted in antifade medium (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and sealed with nail polish. Images from at least 5 different fields of view were obtained using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 Axiophot widefield fluorescence microscope and Zeiss AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany). The transfection efficiency was determined by counting at least 100 cells expressing Fpn and was measured to be 65%.

Cell viability

Cell viability was assessed by the conversion of the dye 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich) to formazan. At times indicated, cells were incubated for 4 hours with MTT (5 mg/ml), and then solvent (isopropyl alcohol containing 0.1 N HCl) was added to dissolve the formazan formed. The resulting formazan was quantified spectrophotometrically at 570 nm, and the background was subtracted at 690 nm using a BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and the total lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. Samples (30 μg) were separated by electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and immunoblotted with rabbit anti-Fpn antibody (1:500; Alpha Diagnostics, Washington, DC). Blots were reprobed with mouse anti-actin (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) as a loading control. Primary antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated IgG, and proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) after exposure to autoradiography film.

Statistical analysis

Data shown are means ± sem and are based on power calculations. Six to 10 mice per group were used for studies. Statistical comparisons were determined by either Student’s t test or 2-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test as appropriate (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Fe deficiency and loading characteristics of Fpn deficiency

Physiologic and hematologic characteristics of ffe/+ mice were compared to +/+ littermates. Body and organ weights in ffe/+ mice were similar to +/+ mice (Table 1). However, ffe/+ mice showed significantly reduced hematocrit values (P < 0.05) and higher liver nonheme Fe levels (P < 0.05) compared to +/+ mice (Table 2). These data are consistent with the phenotypes reported for patients with ferroportin disease (30) and agree with indicators of Fe deficiency and Fe loading previously reported in the ffe/+ mouse model (29).

TABLE 1.

Physiologic characteristics of flatiron (ffe) mice

| Characteristic | +/+ |

ffe/+ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± sem | n | Mean ± sem | n | |

| Body weight, g | 22.3 ± 0.50 | 12 | 23.0 ± 1.10 | 12 |

| Brain weight, g | 0.020 ± 0.0009 | 12 | 0.019 ± 0.0011 | 12 |

| Liver weight, g | 0.880 ± 0.048 | 12 | 0.798 ± 0.042 | 12 |

| Spleen weight, g | 0.055 ± 0.004 | 12 | 0.058 ± 0.004 | 12 |

| Kidney weight, g | 0.326 ± 0.0223 | 12 | 0.307 ± 0.0210 | 12 |

TABLE 2.

Hematologic characteristics of flatiron (ffe) mice

| Characteristic | +/+ |

ffe/+ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± sem | n | Mean ± sem | n | |

| Hematocrit, % | 49.0 ± 0.79 | 10 | 45.9 ± 1.11* | 10 |

| Serum Fe, μg/ml | 13.0 ± 2.14 | 12 | 12.5 ± 1.98 | 12 |

| Liver nonheme Fe, μg/ml | 91.1 ± 6.90 | 10 | 117.1 ± 6.70* | 10 |

P < 0.05 between control (+/+) and flatiron mice (ffe/+).

Flatiron mice display Mn deficiency

To characterize Mn metabolism of flatiron mice, levels of the metal were determined in blood, liver, and bile at 12 wk of age. Blood Mn levels were significantly reduced in ffe/+ mice compared to +/+ mice (0.0107 vs. 0.0123 mg/kg; P = 0.0003), pointing to a deficiency (Fig. 1). Moreover, Mn levels were reduced in the liver (1.06 vs. 0.96 mg/kg; P = 0.0125) and bile (79 vs. 38 mg/kg; P = 0.0204), where it is known that Mn homeostasis occurs with excess metal excreted into bile (39). Reduced Mn levels in both liver and bile would protect ffe/+ mice against Mn deficiency status. Mn status was assessed using blood MnSOD activity as a biomarker. Erythrocyte MnSOD activity was measured at 6 (0.154 vs. 0.096, P = 0.0101), 9 (0.131 vs. 0.089, P = 0.0162), and 16 wk of age (0.170 vs. 0.090 units/mg protein/min; P < 0.0001). As shown in Fig. 2, activity levels of the Mn-requiring enzyme were significantly reduced in ffe/+ mice across all age groups compared to +/+ mice. A role for DMT1 in Mn metabolism has been previously documented (20, 21). To determine whether DMT1 levels were altered in flatiron mice, Western blot experiments were performed with membrane preparations isolated from intestine, liver, and red blood cells collected from +/+ and ffe/+ mice (Supplemental Fig. 1). No significant changes were detected between the 2 groups. Thus, Mn deficiency occurs early after weaning in flatiron mice and does not appear to be associated with changes in DMT1 protein levels.

Figure 1.

Mn levels are reduced in ffe/+ mice. Tissue Mn levels were determined in blood, liver, and bile. Open and solid bars represent +/+ and ffe/+ mice, respectively. Data are means ± sem (n = 7–10 mice/group). *P < 0.05 between +/+ vs. ffe/+ mice; Student's t test.

Figure 2.

Ffe/+ mice have reduced MnSOD activity. MnSOD activity was determined in blood collected via tail vein at the indicated ages. Open and solid bars represent +/+ and ffe/+ mice, respectively. Data are means ± sem (n = 7–10 mice/group). * P < 0.05 between +/+ vs. ffe/+ mice; Student's t test.

Intestinal absorption of 59Fe and 54Mn is reduced in flatiron mice

To examine the influence of Fpn deficiency on intestinal metal absorption, 59Fe was administered to ffe/+ and +/+ mice by intragastric gavage. Fe was reduced to the ferrous form using freshly dissolved ascorbate immediately before instillation. Blood levels of 59Fe were determined 1 hour after administration. Ffe/+ mice had a significantly reduced amount of Fe in blood over the 1-hour period compared to +/+ mice (8.751 vs. 3.978% dose; P = 0.0458) (Fig. 3A). We also characterized blood clearance after intravenous injection of 59Fe. One hour after intravenous injection, the amount of 59Fe in the blood was not significantly different in ffe/+ compared to +/+ mice (Fig. 3B). The calculated bioavailability after correcting for blood clearance of Fe during absorption over the 1-hour time period was significantly diminished (Table 3). To determine the role of Fpn in Mn absorption, we also measured the amount of 54Mn in blood after intragastric gavage or intravenous injection of the radioisotope. Ffe/+ mice displayed lower blood 54Mn levels than +/+ mice 15 minutes after gavage (0.0187 vs. 0.0066% dose; P = 0.0243) (Fig. 3A). There was no difference in blood clearance of 54Mn administered by injection (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that intestinal absorption of both Fe and Mn is reduced by Fpn deficiency, supporting a role for the exporter in assimilation of both metals from the diet (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of Fpn deficiency on absorption of 59Fe and 54Mn after intragastric gavage (A) and intravenous injection (B). Blood levels of 59Fe and 54Mn were determined 1 hour after dose of 59FeCl3 (200 mCi/kg body weight) or 15 minutes after dose of 54MnCl2 (200 mCi/kg body weight) to mice by intragastric gavage and intravenous injection. Open and solid bars represent +/+ and ffe/+ mice, respectively. Data represent means ± sem (n = 7–10 mice/group). *P < 0.05 between +/+ vs. ffe/+ mice; Student's t test.

TABLE 3.

Intestinal bioavailability of Fe and Mn

| Characteristic | WT (%) | FPN-deficient (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 59Fe | 48.0 ± 9.9 | 22.3 ± 7.0* |

| 54Mn | 5.7 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.7* |

Mice were killed after intravenous injection or intragastric gavage of the indicated isotopes (200 mCi/kg body weight). Blood and tissues were collected 1 hour after dose of 59FeCl3 or 15 minutes after dose of 54MnCl2. Blood concentration after intragastric gavage was divided by the concentration determined after intravenous injection to estimate time-variant intestinal bioavailability of each metal. Data are presented as means ± sem.

P < 0.05 between control (+/+) and flatiron mice (ffe/+).

Flatiron mutant H32R fails to protect against Mn toxicity

To further examine the effect of Fpn deficiency on Mn toxicity, dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells were transfected to express empty vector (control), Fpn, or flatiron mutant (H32R). The cells were treated with MnCl2 for 16 h, and cell viability was determined using MTT assay as previously described (40). As shown in Fig. 4A, exogenous expression of wild-type Fpn reversed Mn-induced cytotoxicity in vitro, while transfection with H32R mutant Fpn failed to confer protection. No difference was detected in protein levels between Fpn and H32R mutation (Fig. 4B). The transfection efficiency of SH-SY5Y cells was 38%. To confirm the reliability of these results, identical experiments were performed using HEK293T cells (Fig. 4C–E). Exogenous expression of Fpn and the H32R were again similar based on Western blot analyses (Fig. 4D), and the cytoprotective effects of wild-type exporter in the presence of Mn were confirmed; the mutant lacked this activity as observed in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4C). The transfection efficiency of HEK293T was also greater and was determined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy to be 65% (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Wild-type Fpn, but not flatiron mutant, protects against Mn toxicity. A) SH-SY5Y cells expressing empty vector (control), Fpn (FPN), or flatiron mutant (H32R) were treated with MnCl2 for 16 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Open and solid bars represent vehicle treatment and 1000 μM Mn, respectively. Data are means ± sem as percentage of control (n = 8 samples/treatment). *P < 0.05 compared to control, **P < 0.05 compared among treatments at the same concentration in the different groups. B) Western blot analysis of wild-type (FPN) and ffe/+ mutant (H32R) constructs expressed in SH-SY5Y cells. C) HEK293T cells expressing empty vector (control), Fpn (FPN), or flatiron mutant (H32R) were treated with MnCl2 for 16 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Open and solid bars represent vehicle treatment and 1000 μM Mn, respectively. Data are means ± sem as percentage of control (n = 8 samples/treatment). *P < 0.05 compared to control, **P < 0.05 compared among treatments at the same concentration in the different groups. D) Western blot analysis of wild-type (FPN) and ffe/+ mutant (H32R) constructs expressed in HEK293T cells. E) HEK293T cells were grown on glass coverslips, transfected with control or control vector (pcDNA3.1) or Fpn, then processed for indirect immunofluorescence probing for Fpn. DAPI (blue) stains the nucleus.

In SH-SY5Y cells, expression of wild-type Fpn reduced accumulation of intracellular Mn induced by Mn exposure in treated versus control or nontreated cells (Table 4). Cells transfected with the H32R mutant accumulated even greater Mn levels after exposure. Because Fe deficiency can exacerbate Mn-induced neurotoxicity (40), cellular Fe levels also were measured after Mn exposure. Intracellular Fe levels were not reduced in control, Fpn, or H32R mutant transfected cells with Mn (Table 4). These combined data indicate that the protective effect of Fpn against Mn toxicity results from effects on cellular accumulation of Mn independent of Fe deficiency.

TABLE 4.

Intracellular metal levels in control and Mn-treated SH-SY5Y cells

| Characteristic | Control |

Mn treated |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn, ng/g | Fe, ng/g | Mn, ng/g | Fe, ng/g | |

| Vector | 122.7 ± 0.8 | 1209.2 ± 4.3 | 9260.7* ± 3.3 | 1327.4 ± 1.2 |

| Fpn | 80.6 ± 0.4 | 1773.9 ± 2.3 | 4292.3* ± 1.0 | 2084.0 ± 4.5 |

| H32R | 99.5 ± 0.6 | 838.8 ± 3.0 | 13645.0* ± 0.6 | 863.5 ± 3.4 |

Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells (2 × 10 cm2 dishes) were transfected to express empty vector (Vector), Fpn, or flatiron mutant (H32R). After treatment with or without 500 μM MnCl2 for 16 hours, intracellular levels of Mn and Fe were measured by ICP-MS. Data are represented as means ± sd from at least 5 ICP-MS measurements.

P < 0.05 between control (nontreated) and Mn-treated cells.

DISCUSSION

In vitro studies have suggested that the Fe exporter Fpn also functions in Mn export (24). For example, inducible expression of Fpn in HEK293T cells reduces Mn accumulation and toxicity (26). Kinetic studies in Caco-2 cell monolayers, an in vitro model for intestinal absorption, also support a role for Fpn in basolateral export of Mn (41). However, more recent studies in Xenopus oocytes injected to express Fpn demonstrated efflux of 55Fe, 65Zn, and 57Co but not 64Cu, 109Cd, or 54Mn (25). Our study is the first to examine the function of Fpn in Mn transport in an animal model. To accomplish this goal, we characterized Mn metabolism and intestinal absorption in flatiron mice, a genetic model of Fpn deficiency. Our characterization of these mice show properties reported in previous studies, with heterozygous ffe/+ mice having features of both Fe deficiency and loading. These characteristics recapitulate features of ferroportin disease (29). Importantly, our study is to our knowledge the first to directly demonstrate that intestinal Fe absorption is impaired in flatiron mice, consistent with deficiency of Fe export function across the enterocyte. In addition to defective Fe absorption and Fe homeostasis, we observed that Fpn deficiency in flatiron mice reduces intestinal Mn absorption, lowers blood and liver Mn levels, and is associated with reduced Mn in bile. Mn deficiency was observed as early as 6 weeks of age, with reduced red blood cell MnSOD levels observed in ffe/+ mice compared to +/+ control mice across all age groups studied. In addition, our study shows that Fpn provides neuroprotection against Mn toxicity and confirms loss of function for the Fpn H32R mutation in flatiron mice. These combined results demonstrate Fpn plays a central role in Mn transport and that flatiron mice provide an excellent genetic model to explore the role of this exporter in Mn homeostasis.

Mn homeostasis is tightly maintained by the liver, which is responsible for excreting excess metal into bile (39). After intestinal absorption, Mn is delivered to the liver via portal circulation, providing a protective mechanism against toxicity (42). In the present study, we observed both liver and bile Mn levels are reduced in ffe/+ mice. While it is possible that Fpn deficiency in flatiron mice impairs Mn excretion by the liver into bile, an alternative interpretation is that flatiron mice have reduced Mn levels that would necessarily result in less metal available for excretion into bile. The Mn efflux transporter SLC30A10 most likely plays a role in biliary excretion. SLC30A10 was recently identified as the disease-causing gene in an inherited Mn overload syndrome (15, 16). SLC30A10 is highly expressed in the liver and brain tissues (43) consistent with Mn accumulation seen in these tissues in humans with SLC30A10 mutations. Mn increased both SLC30A10 gene and protein expression in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, suggesting its possible role for the detoxification of Mn (15); this model is consistent with other studies report that SLC30A10 is a cell-surface-localized Mn efflux transporter that protects against Mn toxicity (18). While Fpn is highly expressed in hepatocytes (44) and is located on both the apical and basolateral membrane domains (45, 46), its activity has yet to be fully explored in liver. It is possible that both Fpn and SLC30A10 work together to manage liver Mn levels. Further work is required to define the relationship of these exporters in biliary excretion of Mn in hepatocytes.

The liver is also the major site of synthesis of the regulatory peptide hepcidin (47). Hepcidin is up-regulated by Fe loading and inflammation to induce internalization and degradation of Fpn (48). It has been shown that hepcidin levels are inappropriately low in cases of hereditary hemochromatosis associated with defects in HFE (49, 50). Because mutations in HFE are associated with reduced levels of blood Mn (51) and intestinal absorption of Mn is modified in Hfe knockout mice (52), our results bolster the idea that Fpn is a Mn exporter regulated by hepcidin. Mn has also been shown to induce hepcidin expression in hepatocytes, providing a further link between hepcidin and Mn homeostasis (53). The central control of Fe and Mn homeostasis by hepcidin underscores the relationships between these metals (54). If indeed high Mn induces hepcidin in the liver, this setting provides a mechanism to down-regulate dietary Mn absorption by Fpn. Further in vivo studies are necessary to explore these possibilities.

Although Mn loading due to ingestion is relatively rare due to hepatic first-pass elimination of the excess metal, intake of airborne Mn bypasses the biliary excretion route and inhaled Mn is efficiently transported into the body, including the brain, through the nasal epithelium (55–57). Under these conditions, Mn can be a potent neurotoxicant. We have shown that Mn absorption across the olfactory epithelium into the brain is enhanced by Fe deficiency and that this pathway requires DMT1 (21). Studies in our laboratory further demonstrated that Mn-induced neuronal cell death is potentiated by Fe deficiency, most likely through up-regulation of DMT1 (40). In the present study, we found that dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells and human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells transfected to express wild-type Fpn have reduced Mn-induced cytotoxicity. Consistent with these data, ICP-MS analysis confirmed wild-type Fpn expression reduces intracellular Mn after exposure. The flatiron H32R mutant failed to confer cytoprotection from metal toxicity. ICP-MS measurements show that SH-SY5Y cells transfected with the mutant had levels of cellular Mn higher than control, a result that is anticipated from its dominant negative effect and that further confirms functional loss of its activity. It is important to note that cellular Fe levels are slightly increased in SH-SY5Y cells expressing Fpn, a finding that indicates that Mn-induced toxicity is not an indirect effect of Fe deficiency. Nonetheless, overexpression of Fpn might be anticipated to promote Fe depletion. The observed differences in cellular metal content can be explained by differences between the cellular trafficking mechanisms of the 2 metals. Once inside cells, Fe is either deposited in ferritin or incorporated into mitochondria for heme metabolism and synthesis of iron–sulfur clusters. The relationship between import and export of Fe and its metabolic disposition is governed by Fe-responsive proteins that interact with Fe-response elements present in transcripts of importers (DMT1, transferrin receptor-1), exporters (Fpn), and storage proteins (ferritin), as well as factors involved in heme synthesis (aminolevulinic acid synthetase). Greater Fe export may be balanced by increased Fe import, and the consequential expansion of intracellular Fe stores detected by ICP-MS. Mn, on the other hand, exists in a more labile pool that is readily available for export and that is independent of the Fe metabolic response. In this respect, levels of DMT1, a known Mn and Fe importer, would be reduced by higher cellular Fe levels, suggesting that the observed reduction in cellular Mn content must necessarily reflect greater export activity. Further studies will be required to uncover the mechanisms involved in metal homeostasis influenced by Fpn.

The fact that the flatiron mutation H32R does not confer a cytoprotective effect in SH-SY5Y cells suggests that mutations in Fpn may exacerbate Mn neurotoxicity. Fpn is not only highly expressed in macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system, intestinal duodenum, and hepatocytes (22, 28, 58) but it is also ubiquitously expressed in murine brain (59), including the olfactory region (52). Thus, it will be important to test whether Fpn functions as a Mn exporter in the brain and how ferroportin disease may influence the metal’s toxicity. This genetic disorder is caused by missense mutations in the Fpn gene and is the only type of hemochromatosis that has a dominant transmission pattern (30). Ferroportin disease has distinctive clinical pathologies, including early increase in serum ferritin in spite of low-normal transferrin saturation, progressive Fe accumulation in organs (predominantly in macrophages and liver), and marginal anemia with low tolerance to phlebotomy (30). Although the prevalence of this genetic disorder is unknown, ferroportin disease affects individuals of all races and ethnicities (60). Understanding a relationship between Fpn mutation and Mn metabolism will be important to determine the influence of Fpn deficiency on Mn neurotoxicity. Chronic Mn exposure is associated with changes in movement, gait, strength, and alterations in motor function (61, 62). To date, no neurologic symptoms are reported from patients with Fpn mutations. The effect of Fpn deficiency on brain Mn metabolism and Mn neurotoxicity in flatiron mice certainly warrants further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to M.W.R. (R01ES0146380) and Y.A.S. (K99ES024340).

Glossary

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DMT1

divalent metal transporter-1

- Fe

iron

- Fpn

ferroportin

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- Mn

manganese

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Golub M. S., Hogrefe C. E., Germann S. L., Tran T. T., Beard J. L., Crinella F. M., Lonnerdal B. (2005) Neurobehavioral evaluation of rhesus monkey infants fed cow’s milk formula, soy formula, or soy formula with added manganese. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 27, 615–627. Erratum in Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2012;34:220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morello M., Zatta P., Zambenedetti P., Martorana A., D’Angelo V., Melchiorri G., Bernardi G., Sancesario G. (2007) Manganese intoxication decreases the expression of manganoproteins in the rat basal ganglia: an immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. Bull. 74, 406–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aschner M., Guilarte T. R., Schneider J. S., Zheng W. (2007) Manganese: recent advances in understanding its transport and neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 221, 131–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong J. S., Hung C. R., Seth P. K., Mason G., Bondy S. C. (1984) Effect of manganese treatment on the levels of neurotransmitters, hormones, and neuropeptides: modulation by stress. Environ. Res. 34, 242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada M., Ohno S., Okayasu I., Okeda R., Hatakeyama S., Watanabe H., Ushio K., Tsukagoshi H. (1986) Chronic manganese poisoning: a neuropathological study with determination of manganese distribution in the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 70, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucchini R., Bergamaschi E., Smargiassi A., Festa D., Apostoli P. (1997) Motor function, olfactory threshold, and hematological indices in manganese-exposed ferroalloy workers. Environ. Res. 73, 175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran T. T., Chowanadisai W., Crinella F. M., Chicz-DeMet A., Lönnerdal B. (2002) Effect of high dietary manganese intake of neonatal rats on tissue mineral accumulation, striatal dopamine levels, and neurodevelopmental status. Neurotoxicology 23, 635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mena I., Horiuchi K., Burke K., Cotzias G. C. (1969) Chronic manganese poisoning. Individual susceptibility and absorption of iron. Neurology 19, 1000–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sriram K., Lin G. X., Jefferson A. M., Roberts J. R., Chapman R. S., Chen B. T., Soukup J. M., Ghio A. J., Antonini J. M. (2010) Dopaminergic neurotoxicity following pulmonary exposure to manganese-containing welding fumes. Arch. Toxicol. 84, 521–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbeau A. (1984) Manganese and extrapyramidal disorders (a critical review and tribute to Dr. George C. Cotzias). Neurotoxicology 5, 13–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaldson J. (1987) The physiopathologic significance of manganese in brain: its relation to schizophrenia and neurodegenerative disorders. Neurotoxicology 8, 451–462 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zayed J., Gérin M., Loranger S., Sierra P., Bégin D., Kennedy G. (1994) Occupational and environmental exposure of garage workers and taxi drivers to airborne manganese arising from the use of methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl in unleaded gasoline. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 55, 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frumkin H., Solomon G. (1997) Manganese in the U.S. gasoline supply. Am. J. Ind. Med. 31, 107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prahalad A. K., Soukup J. M., Inmon J., Willis R., Ghio A. J., Becker S., Gallagher J. E. (1999) Ambient air particles: effects on cellular oxidant radical generation in relation to particulate elemental chemistry. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 158, 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quadri M., Federico A., Zhao T., Breedveld G. J., Battisti C., Delnooz C., Severijnen L. A., Di Toro Mammarella L., Mignarri A., Monti L., Sanna A., Lu P., Punzo F., Cossu G., Willemsen R., Rasi F., Oostra B. A., van de Warrenburg B. P., Bonifati V. (2012) Mutations in SLC30A10 cause parkinsonism and dystonia with hypermanganesemia, polycythemia, and chronic liver disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 467–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuschl K., Clayton P. T., Gospe S. M. Jr., Gulab S., Ibrahim S., Singhi P., Aulakh R., Ribeiro R. T., Barsottini O. G., Zaki M. S., Del Rosario M. L., Dyack S., Price V., Rideout A., Gordon K., Wevers R. A., Chong W. K., Mills P. B. (2012) Syndrome of hepatic cirrhosis, dystonia, polycythemia, and hypermanganesemia caused by mutations in SLC30A10, a manganese transporter in man. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 457–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeWitt M. R., Chen P., Aschner M. (2013) Manganese efflux in Parkinsonism: insights from newly characterized SLC30A10 mutations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 432, 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyva-Illades D., Chen P., Zogzas C. E., Hutchens S., Mercado J. M., Swaim C. D., Morrisett R. A., Bowman A. B., Aschner M., Mukhopadhyay S. (2014) SLC30A10 is a cell surface–localized manganese efflux transporter, and parkinsonism-causing mutations block its intracellular trafficking and efflux activity. J. Neurosci. 34, 14079–14095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitsanakis V. A., Zhang N., Garcia S., Aschner M. (2010) Manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe): interdependency of transport and regulation. Neurotox. Res. 18, 124–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chua A. C., Morgan E. H. (1997) Manganese metabolism is impaired in the Belgrade laboratory rat. J. Comp. Physiol. B 167, 361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson K., Molina R. M., Donaghey T., Schwob J. E., Brain J. D., Wessling-Resnick M. (2007) Olfactory uptake of manganese requires DMT1 and is enhanced by anemia. FASEB J. 21, 223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donovan A., Brownlie A., Zhou Y., Shepard J., Pratt S. J., Moynihan J., Paw B. H., Drejer A., Barut B., Zapata A., Law T. C., Brugnara C., Lux S. E., Pinkus G. S., Pinkus J. L., Kingsley P. D., Palis J., Fleming M. D., Andrews N. C., Zon L. I. (2000) Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature 403, 776–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKie A. T., Marciani P., Rolfs A., Brennan K., Wehr K., Barrow D., Miret S., Bomford A., Peters T. J., Farzaneh F., Hediger M. A., Hentze M. W., Simpson R. J. (2000) A novel duodenal iron-regulated transporter, IREG1, implicated in the basolateral transfer of iron to the circulation. Mol. Cell 5, 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madejczyk M. S., Ballatori N. (2012) The iron transporter ferroportin can also function as a manganese exporter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 651–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell C. J., Shawki A., Ganz T., Nemeth E., Mackenzie B. (2014) Functional properties of human ferroportin, a cellular iron exporter reactive also with cobalt and zinc. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 306, C450–C459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin Z., Jiang H., Lee E. S., Ni M., Erikson K. M., Milatovic D., Bowman A. B., Aschner M. (2010) Ferroportin is a manganese-responsive protein that decreases manganese cytotoxicity and accumulation. J. Neurochem. 112, 1190–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park B. Y., Chung J. (2008) Effects of various metal ions on the gene expression of iron exporter ferroportin-1 in J774 macrophages. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2, 317–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donovan A., Lima C. A., Pinkus J. L., Pinkus G. S., Zon L. I., Robine S., Andrews N. C. (2005) The iron exporter ferroportin/Slc40a1 is essential for iron homeostasis. Cell Metab. 1, 191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zohn I. E., De Domenico I., Pollock A., Ward D. M., Goodman J. F., Liang X., Sanchez A. J., Niswander L., Kaplan J. (2007) The flatiron mutation in mouse ferroportin acts as a dominant negative to cause ferroportin disease. Blood 109, 4174–4180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pietrangelo A. (2004) The ferroportin disease. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 32, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chlosta S., Fishman D. S., Harrington L., Johnson E. E., Knutson M. D., Wessling-Resnick M., Cherayil B. J. (2006) The iron efflux protein ferroportin regulates the intracellular growth of Salmonella enterica. Infect. Immun. 74, 3065–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahousse S. A., Carter J. J., Xu X. J., Wands J. R., de la Monte S. M. (2006) Differential growth factor regulation of aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase family genes in SH-Sy5y human neuroblastoma cells. BMC Cell Biol. 7, 41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le M. T., Xie H., Zhou B., Chia P. H., Rizk P., Um M., Udolph G., Yang H., Lim B., Lodish H. F. (2009) MicroRNA-125b promotes neuronal differentiation in human cells by repressing multiple targets. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 5290–5305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S., Zhang S., Bromley-Brits K., Cai F., Zhou W., Xia K., Mittelholtz J., Song W. (2011) Transcriptional Regulation of TMP21 by NFAT. Mol. Neurodegener. 6, 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yonashiro R., Kimijima Y., Shimura T., Kawaguchi K., Fukuda T., Inatome R., Yanagi S. (2012) Mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase MITOL blocks S-nitrosylated MAP1B-light chain 1-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 2382–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao C., Rioult-Pedotti M. S., Migani P., Yu C. J., Tiwari R., Parang K., Spaller M. R., Goebel D. J., Marshall J. (2013) Impairment of TrkB-PSD-95 signaling in Angelman syndrome. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie L., Tiong C. X., Bian J. S. (2012) Hydrogen sulfide protects SH-SY5Y cells against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 303, C81–C91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soundararajan R., Wishart A. D., Rupasinghe H. P., Arcellana-Panlilio M., Nelson C. M., Mayne M., Robertson G. S. (2008) Quercetin 3-glucoside protects neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells in vitro against oxidative damage by inducing sterol regulatory element–binding protein-2–mediated cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2231–2245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertinchamps A. J., Miller S. T., Cotzias G. C. (1966) Interdependence of routes excreting manganese. Am. J. Physiol. 211, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seo Y. A., Li Y., Wessling-Resnick M. (2013) Iron depletion increases manganese uptake and potentiates apoptosis through ER stress. Neurotoxicology 38, 67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X., Xie J., Lu L., Zhang L., Zhang L., Zou Y., Wang Q., Luo X., Li S. (2013) Kinetics of manganese transport and gene expressions of manganese transport carriers in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Biometals 26, 941–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finley J. W., Johnson P. E., Johnson L. K. (1994) Sex affects manganese absorption and retention by humans from a diet adequate in manganese. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 60, 949–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosomworth H. J., Thornton J. K., Coneyworth L. J., Ford D., Valentine R. A. (2012) Efflux function, tissue-specific expression and intracellular trafficking of the Zn transporter ZnT10 indicate roles in adult Zn homeostasis. Metallomics 4, 771–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramey G., Deschemin J. C., Durel B., Canonne-Hergaux F., Nicolas G., Vaulont S. (2010) Hepcidin targets ferroportin for degradation in hepatocytes. Haematologica 95, 501–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laftah A. H., Sharma N., Brookes M. J., McKie A. T., Simpson R. J., Iqbal T. H., Tselepis C. (2006) Tumour necrosis factor alpha causes hypoferraemia and reduced intestinal iron absorption in mice. Biochem. J. 397, 61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas C., Oates P. S. (2004) Ferroportin/IREG-1/MTP-1/SLC40A1 modulates the uptake of iron at the apical membrane of enterocytes. Gut 53, 44–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zumerle S., Mathieu J. R., Delga S., Heinis M., Viatte L., Vaulont S., Peyssonnaux C. (2014) Targeted disruption of hepcidin in the liver recapitulates the hemochromatotic phenotype. Blood 123, 3646–3650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tussing-Humphreys L., Pusatcioglu C., Nemeth E., Braunschweig C. (2012) Rethinking iron regulation and assessment in iron deficiency, anemia of chronic disease, and obesity: introducing hepcidin. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 112, 391–400 Erratum in J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012;112:762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad K. A., Ahmann J. R., Migas M. C., Waheed A., Britton R. S., Bacon B. R., Sly W. S., Fleming R. E. (2002) Decreased liver hepcidin expression in the Hfe knockout mouse. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 29, 361–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piperno A., Girelli D., Nemeth E., Trombini P., Bozzini C., Poggiali E., Phung Y., Ganz T., Camaschella C. (2007) Blunted hepcidin response to oral iron challenge in HFE-related hemochromatosis. Blood 110, 4096–4100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Claus Henn B., Kim J., Wessling-Resnick M., Téllez-Rojo M. M., Jayawardene I., Ettinger A. S., Hernández-Avila M., Schwartz J., Christiani D. C., Hu H., Wright R. O. (2011) Associations of iron metabolism genes with blood manganese levels: a population-based study with validation data from animal models. Environ. Health 10, 97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J., Buckett P. D., Wessling-Resnick M. (2013) Absorption of manganese and iron in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. PLoS ONE 8, e64944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartnikas T. B. (2012) Known and potential roles of transferrin in iron biology. Biometals 25, 677–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roth J. A., Garrick M. D. (2003) Iron interactions and other biological reactions mediating the physiological and toxic actions of manganese. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tjälve H., Henriksson J., Tallkvist J., Larsson B. S., Lindquist N. G. (1996) Uptake of manganese and cadmium from the nasal mucosa into the central nervous system via olfactory pathways in rats. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 79, 347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brenneman K. A., Wong B. A., Buccellato M. A., Costa E. R., Gross E. A., Dorman D. C. (2000) Direct olfactory transport of inhaled manganese ((54)MnCl(2)) to the rat brain: toxicokinetic investigations in a unilateral nasal occlusion model. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 169, 238–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nong A., Teeguarden J. G., Clewell H. J. III, Dorman D. C., Andersen M. E. (2008) Pharmacokinetic modeling of manganese in the rat, IV: assessing factors that contribute to brain accumulation during inhalation exposure. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 71, 413–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knutson M. D., Oukka M., Koss L. M., Aydemir F., Wessling-Resnick M. (2005) Iron release from macrophages after erythrophagocytosis is up-regulated by ferroportin 1 overexpression and down-regulated by hepcidin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 1324–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boserup M. W., Lichota J., Haile D., Moos T. (2011) Heterogenous distribution of ferroportin-containing neurons in mouse brain. Biometals 24, 357–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pietrangelo A., Caleffi A., Corradini E. (2011) Non-HFE hepatic iron overload. Semin. Liver Dis. 31, 302–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guilarte T. R. (2010) Manganese and Parkinson’s disease: a critical review and new findings. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1071–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Racette B. A., McGee-Minnich L., Moerlein S. M., Mink J. W., Videen T. O., Perlmutter J. S. (2001) Welding-related parkinsonism: clinical features, treatment, and pathophysiology. Neurology 56, 8–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.