Abstract

Sphingosine kinase 1 (SK1), the enzyme responsible for sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) production, is overexpressed in many human solid tumors. However, its role in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) has not been described previously. ccRCC cases are usually associated with mutations in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) and subsequent normoxic stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). We previously showed that HIF-2α up-regulates SK1 expression during hypoxia in glioma cells. Therefore, we hypothesized that the stabilized HIF in ccRCC cells will be associated with increased SK1 expression. Here, we demonstrate that SK1 is overexpressed in 786-0 renal carcinoma cells lacking functional VHL, with concomitant high S1P levels that appear to be HIF-2α mediated. Moreover, examining the TCGA RNA seq database shows that SK1 expression was ∼2.7-fold higher in solid tumor tissue from ccRCC patients, and this was associated with less survival. Knockdown of SK1 in 786-0 ccRCC cells had no effect on cell proliferation. On the other hand, this knockdown resulted in an ∼3.5-fold decrease in invasion, less phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and an ∼2-fold decrease in angiogenesis. Moreover, S1P treatment of SK1 knockdown cells resulted in phosphorylation of FAK and invasion, and this was mediated by S1P receptor 2. These results suggest that higher SK1 and S1P levels in VHL-defective ccRCC could induce invasion in an autocrine manner and angiogenesis in a paracrine manner. Accordingly, targeting SK1 could reduce both the invasion and angiogenesis of ccRCC and therefore improve the survival rate of patients.—Salama, M. F., Carroll, B., Adada, M., Pulkoski-Gross, M., Hannun, Y. A., Obeid, L. M. A novel role of sphingosine kinase-1 in the invasion and angiogenesis of VHL mutant clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Keywords: sphingosine 1-phosphate, S1P receptor, focal adhesion kinase, HIF-2

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most prevalent type of kidney cancer that accounts for 70–80% of cases (1). It is usually characterized by inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein that is caused by deletion on chromosome 3p (2), gene mutations (3), or hypermethylation of the promoter (4). The VHL gene product, pVHL, has several functions; however, its main role is to regulate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). VHL serves as a recognition element for a ubiquitin ligase that induces proteasomal degradation of the α subunits of HIF following the hydroxylation of one or both prolyl residues of these subunits (5, 6). Therefore, the lack of functional pVHL is associated with normoxic stabilization of HIFs (7). HIF-2α is believed to play a key role in VHL-defective renal carcinogenesis as some renal carcinomas produce HIF-2α alone or both HIF-1 and 2α (5). Moreover, in VHL-defective tumors, ablation of HIF-2α has been shown to be sufficient for tumor growth suppression in vivo (8). Interestingly, the tumor growth suppressive effect associated with restoration of pVHL was overridden by HIF-2α overexpression (9). Although both HIF-1α and HIF-2α share some of their biological effects, each of them has a unique ability to regulate particular genes (10). HIF-1α is mainly involved in regulating enzymes of the glycolytic pathway (11, 12); conversely, HIF-2α, through its interaction with c-Myc, is mainly involved in tumor cell progression (13). In addition, we previously showed that HIF-2α transcriptionally up-regulates sphingosine kinase 1 (SK1) expression during hypoxia in glioma cells (14).

SK1 and SK2 are the 2 isoforms of sphingosine kinases that have been identified and cloned in mammals (15, 16). Although they catalyze the conversion of sphingosine into sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), these 2 isoforms have been shown to have different cellular localization and biologic functions (17, 18). SK1 has prosurvival function and is mainly localized in the cytosol (19, 20). Conversely, SK2 is important for cellular proliferation, and its inhibition sensitizes cells to apoptotic stimuli (21, 22). SK2 is localized in nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria (23). Overexpression of SK1 has been documented in different cancer types, including breast (24), lung (25), gastric (26), thyroid (27), head and neck (28), and colon cancers (29). Moreover, SK1 expression and S1P levels could be used as biomarkers of tumor malignancies as both have been shown to be correlated with survival and cancer grade in clinical studies (24, 26). It is clear now that SK1 plays a role in different cancers; however, such a role has not previously been addressed in ccRCC. Therefore, we aimed to study the potential role of SK1 in ccRCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

RPMI 1640 medium, DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, PBS, Lipofectamine 2000, Lipofectamine RNAiMAX, PureLink RNA Mini Kit, Superscript III first strand synthesis kit, and calcein AM fluorescent dye were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). Monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody and 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), puromycin dihydrochloride, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibitor 14, RIPA lysis buffer system, and horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr397), anti-FAK, anti-VHL, and anti-SK1 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-HIF-2α was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA). Anti-HIF-1α was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Corning Biocoat Tumor Invasion Systems (EF8976D) was from Corning (Tewksbury, MA, USA). The chemiluminescence kit and BCA kit were from Thermo Scientific (Suwanee, GA, USA). iTAQ master mix was purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). S1P and d-erythro-17-carbon sphingosine (C17-Sph) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). SKi-II (4-[4-(4-chloro-phenyl)-thiazol-2-ylamino]-phenol, VPC23019, and JTE-013 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). CYM50358 was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). All plasmids used for production of lentiviral particles (psPAX2, PLKO.1, and pMD2G) were kindly provided by Dr. Leah Siskind (University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY, USA).

Cell culture and small interference RNA

VHL-defective clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells, 786-0, and those expressing wild-type VHL protein, WT-8 cells, were provided by Dr. Harry A. Drabkin (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% FBS. WT-8 cells were grown in the same media supplemented with 1 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). HEK-239T cells were purchased originally from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and were grown in DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% FBS. All cell lines were incubated in standard culture conditions: 37°C and 5% CO2.

Gene silencing was carried out using siRNA directed against human HIF-2α (Silencer Pre-Designed siRNA, siRNA ID: 106447; Life Technologies), S1PR2, Hs_EDG5_6 FlexiTube siRNA SI02663227 (FlexiTube siRNA, experimentally verified; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and with AllStars negative control siRNA (Qiagen). Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX according to the manufacturer's protocol. For siRNA experiments, 786-0 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at ∼100,000 cells per well and transfected with 20 nM siRNA for 48 hours, followed by RNA and protein extraction to validate target gene knockdown. S1PR2 siRNA transfections were conducted as described previously (30), and cells were serum starved 48 hours after transfection and then treated with S1P.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

RNA extraction was performed using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit following the manufacturer's protocol. One microgram of RNA was then used for cDNA synthesis by using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR was carried out using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The following TaqMan probes (Life Technologies) were used: human SK1 (ID: Hs01116530_g1), human HIF-2α (Hs00368739_m1), human SK2 (ID: Hs01016543_g1), and human β-actin (ID: Hs99999903_m1), which was used as a housekeeping gene. Cycle threshold (CT) values were obtained for each gene of interest and β-actin. ΔCt values were calculated, and the relative gene expression normalized to control samples was calculated from ΔΔCt values.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then directly lysed in cold RIPA buffer containing 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Equal amounts of protein (10 µg) were boiled in Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad), and separated by SDS-PAGE (4–15%, Tris-HCl) using the Bio-Rad Criterion system. Separated proteins were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS-0.1% Tween-20 for at 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 or 1:20,000 for β-actin were then added to membranes and incubated at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed 3 times with PBS-0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with diluted 1:5000 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (ThermoScientific, Suwanee, GA, USA) and exposed to X-ray films that were then processed and scanned.

Short-hairpin RNA constructs and lentiviral infections

Lentivirus particles were produced in HEK-293T cells transfected with 500 ng psPAX2, 50 ng PMD2G, and 500 ng lentiviral plasmid (pLKO.1) containing either SK1 or a nontargeted sequence using Lipofectamine 2000. 786-0 cells were then infected with the lentiviral particles with polybrene (8 µg/ml) and selected for puromycin resistance (5 µg/ml) for ≥1 week, followed by RNA and protein extraction to validate gene silencing by quantitative PCR and Western blotting, respectively.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined by colorimetric assay using MTT (Sigma-Aldrich). In brief, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 50,000 cells per well. The next morning, for the zero time point, the medium was replaced with 1 ml fresh medium plus 1 ml MTT solution (5 mg/ml), and cells were incubated for 3 hours. The solution was then carefully removed, followed by addition of 2 ml DMSO (Invitrogen) to each well to solubilize crystals. The absorbance of each sample was measured at 550 nm. The same was performed after 24, 48, and 72 hours. Triplicate measurements were performed for each time point.

Plasmid constructs and transient transfections

Human SK1 (GenBank accession no. AF200328) cDNA was subcloned into NheI and NotI sites of pcDNA3.1-mCherry.Zeo (31). 786-0 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at ∼100,000 cells per well in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium 1 day before transfection. On the next day, the cells were transfected with 1 μg pcDNA3.1-mCherry.SK1 or empty vector using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated for 48 hours followed by protein extraction and Western blot analysis.

C17-Sph labeling

786-0, WT-8, or short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) stably expressing cells were plated at 150,000 cells per 60 mm dish. Once ∼90% confluent, cells were incubated with 1 μM C17 sphingosine for 20 minutes. The cells were washed with PBS; 2 ml cell extraction mixture (2:3 70% isopropanol/ethyl acetate) then was directly added to the cells. The cells were then gently scraped, and extracts were sent for analysis at the Lipidomics Core Facility of Stony Brook University Medical Center.

Mass spectrometry to measure sphingolipid levels

For extracellular S1P levels, media were aspirated and transferred to glass tubes, and an equal volume of medium extraction mixture (15:85 isopropanol/ethyl acetate) was added. For lipid extraction, cells were washed with PBS, the cells were then directly lysed with 2 ml cell extraction mixture (2:3 70% isopropanol/ethyl acetate) followed by gentle scraping of the cell from the culture plate, and the lysate then was transferred to 15 ml Falcon tubes. The lipid extracts were then sent for analysis at the Lipidomics Core Facility at Stony Brook University Medical Center. Data were normalized by total inorganic phosphate (Pi) present in the sample (32) after a Bligh and Dyer extraction (33). Cellular sphingolipid levels were expressed as picomoles per nmoles Pi.

Cellular invasion assays

Cell invasion experiments were performed using Corning Biocoat Tumor Invasion Systems according to the manufacturer’s protocol with slight modifications as previously described (30). In brief, after 4 h of serum starvation, cells were trypsinized and resuspended at 150,000 cells/ml. These cells were then placed in the apical chamber of the transwell insert at a volume of 500 µl. Inhibitors such as JTE-013, VPC 23019, SKi-II, or the FAK inhibitor were mixed with the cells at this stage. Media containing serum or S1P were added to the bottom well of the insert at a volume of 750 µl. Cells were allowed to invade for 48 hours under normal cell culture conditions. Cells were washed twice with PBS and then stained with 4 µg/ml calcein AM (Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Invading cells were then quantified by measuring their fluorescence using a Spectra-Max M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Survival analysis

The patient survival data were obtained from the TCGA ccRCC project. On the basis of the expression levels of SK1 in TCGA RNA-seq data, patients were ranked into upper half (SK1 expression > median) and lower half (SK1 expression < median) groups. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed on 2 patient groups, followed by a log-rank test for statistical significance.

Chorioallantoic membrane assay

Specific pathogen-free chicken eggs were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (North Franklin, CT, USA). In brief, eggs were incubated at 37°C and 65% relative humidity with rocking for 3 days. After the initial incubation, eggs were cracked, and chicken embryos were placed into sterile Petri dishes and allowed to develop further for maturation of the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) for another 7 days. For each sponge, 500,000 cells were resuspended in 20 µl PBS, supplemented with 0.5 mM both Ca2+ and Mg2+. The resuspended cells were treated with the indicated inhibitors and incubated with sterile gelatin sponges for 30 minutes at 37°C. Next, 2–3 sponges were placed on each chicken, which were then allowed to incubate for 4 days at 37°C and 65% relative humidity. The sponges were imaged on the fourth day of incubation with the sponges. Angiogenesis was assessed by counting the number of vessels that grew toward the sponge.

Statistical analysis

The data are represented as means ± se. Two-tailed unpaired Student t test and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Incorporated, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

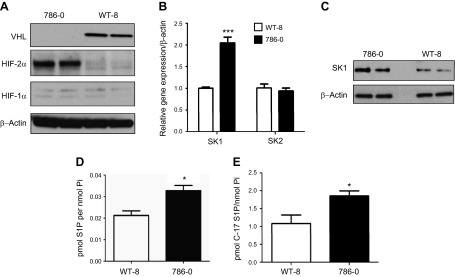

VHL-defective ccRCC 786-0 cells showed higher SK1 expression and higher S1P levels

To examine the effect of stabilized HIF in VHL-defective renal carcinoma cells on SK1 expression, protein extracts and cDNA from VHL-defective, 786-0, and those stably expressing VHL, WT-8, cells were subjected to Western blot and quantitative PCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 1A, 786-0 cells showed higher levels of HIF-2α compared with WT-8 cells, with undetectable HIF-1α protein in both cell lines, consistent with results showing that this cell type expresses HIF-2α and not HIF-1α (5). SK1 mRNA and protein expressions were significantly higher in 786-0 cells, with no difference in SK2 message level (Fig. 1B, C). To determine whether the observed increase in SK1 protein expression in VHL-defective cells results in increased output of the enzyme, we measured cellular levels of its lipid product S1P, which were found to be elevated in the 786-0 cells (Fig. 1D). In further evaluation of cellular SK1 activity, C17-sphingosine labeling was performed (1 µM C17-Sph for 20 min), followed by measurement of acute conversion of C17-Sph to C17-S1P. As shown in Fig. 1E, 786-0 cells showed higher levels of C17-S1P than WT-8 cells, indicating ongoing higher activity of the enzyme.

Figure 1.

VHL-defective 786-0 cells showed higher expression of HIF-2α and SK1 with higher S1P levels. A) Proteins were extracted from VHL-defective (786-0) cells and those stably expressing VHL (WT-8) and subjected to Western blot analysis using VHL, HIF-2α, and HIF-1α antibodies; β-actin served as a protein loading control. B) Total RNA was extracted from 786-0 and WT-8 cells, and then it was reverse transcribed and used for quantitative PCR assay using SK1- and SK2-specific TaqMan probes. C) Protein samples from 786-0 and WT-8 cells were used for Western blot analysis using SK1 antibody and β-actin as a loading control. Lipids were extracted from unlabeled (D) or C17-sphingosine–labeled (E) 786-0 and WT-8 cells; S1P and C-17 S1P (C-17 S1P) were determined by mass spectrometry. Data are means of triplicate measurements and are expressed as picomoles of lipid per nanomole Pi. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

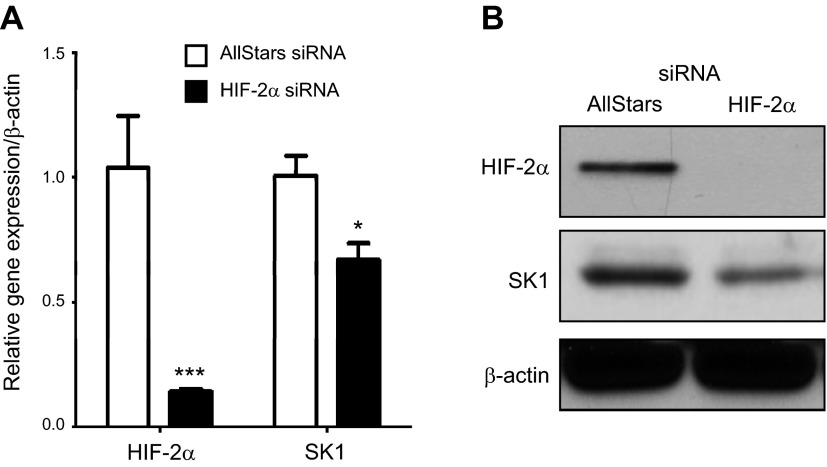

Effect of HIF-2α down-regulation on SK1 expression in 786-0 cells

We previously showed that HIF-2α regulates SK1 transcriptionally in response to hypoxia in glioma cells (14). To examine whether stabilized HIF-2α protein in VHL-defective 786-0 cells is responsible for higher SK1 expression, HIF-2α was down-regulated using siRNA technology. Cells were transfected with AllStars negative control or HIF-2α siRNA for 48 hours. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, HIF-2α was efficiently down-regulated by siRNA at message and protein levels. It is noteworthy that SK1 message and protein levels were decreased with HIF-2α siRNA treatment. These data suggest that stabilized HIF-2α is involved in SK1 up-regulation in VHL-defective renal carcinoma cells.

Figure 2.

Knocking down of HIF-2α in 786-0 cells is associated with less SK1 expression. 786-0 cells were transfected with either AllStars negative control or HIF-2α siRNA for 48 hours, followed by RNA and protein extraction. Analyses of HIF-2α and SK1 message by quantitative PCR (A) and protein levels by Western blotting (B) were performed. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001; n ≥ 3.

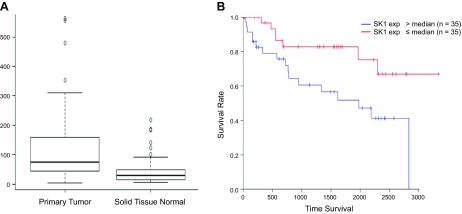

SK1 is up-regulated in ccRCC patients and correlates with clinical outcome

To assess expression of SK1 in ccRCC patients, TCGA RNA seq datasets were analyzed from 72 paired normal and ccRCC tumor samples. As shown in Fig. 3A, SK1 mRNA expression is ∼2.7-fold higher in the primary tumor than in normal tissue. Moreover, the survival rates of patients with the top 50% SK1 expression were significantly lower than those with the bottom 50% SK1 expression (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrate a clear correlation between high SK1 expression in ccRCC and poor clinical outcome.

Figure 3.

SK1 is highly expressed in primary tumors and associated with less survival rate in ccRCC patients. A) A box blot was generated from TCGA RNA seq datasets of paired normal and ccRCC tumor samples (72 samples) for SK1 gene expression, P = 0.00000457. B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of ccRCC patients from TCGA database. Based on SK1 mRNA levels in their tumors, patients were equally divided into 2 groups (top and bottom 50% of SK1 expression); log-rank test, P = 0.000000235.

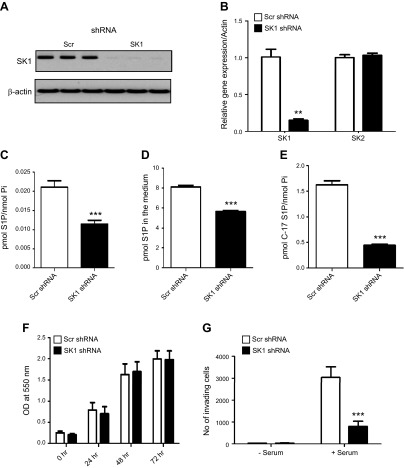

SK1 down-regulation is associated with less invasive phenotype in ccRCC 786-0 cells

To explore the role of the high SK1 expression in ccRCC biology, SK1 was down-regulated using shRNA technology. Cells stably expressing scrambled (scr) or SK1 shRNA were selected using puromycin followed by validation of gene knockdown using quantitative PCR and Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, B, SK1 was efficiently down-regulated in SK1 shRNA-expressing compared with scr shRNA-expressing cells at protein and message levels, with no difference in SK2 message level. Moreover, cellular and extracellular S1P levels were decreased with SK1 knockdown (Fig. 4C, D). SK1 activity, assessed by C17-sphingosine labeling, was also decreased with SK1 down-regulation (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Down-regulation of SK1 expression does not affect proliferation but decreases the invasion of ccRCC. SK1 knockdown was achieved by introducing specific shRNA in 786-0 cells. Knockdown was validated by quantitative PCR (A) and Western blotting (B). Silencing of SK1 was associated with a significant decrease in intracellular (C), extracellular (D), and C-17 S1P (E) levels. F) Cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay; assay was performed in triplicate for each time point (0, 24, 48, and 72 hours). G) 786-0 cells stably expression scrambled (Scr) or SK1 shRNA were serum starved in serum-free medium for 4 hours, plated in the apical chamber of Matrigel-coated transwell inserts, and allowed to invade for 48 hours toward serum. Invading cells were stained with fluorescent dye and counted. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n ≥ 3.

SK1 has previously been shown to be involved in different biologic processes, including cell proliferation, survival, progression, and metastasis (34, 35). To examine the biological consequences of SK1 down-regulation, cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay in cells stably expressing scr or SK1 shRNA. As shown in Fig. 4F, no differences were observed in proliferation between the 2 cell lines. The invasiveness of shRNA expressing cells was then determined by cell invasion assays using transwell chambers. Both cells were allowed to invade toward complete growth medium for 48 hours (Fig. 4G). Knocking down SK1 resulted in 3-fold reduction in the invasion of 786-0 cells, suggesting that SK1 plays an important role in cellular invasion.

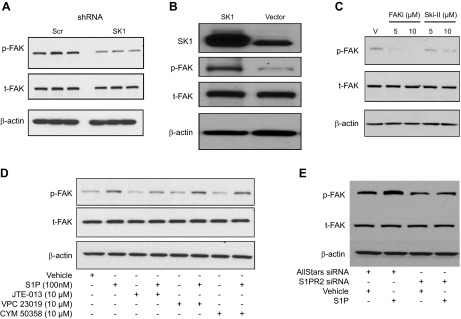

SK1 induces FAK phosphorylation in an S1P-S1PR2–dependent manner

To further explore the mechanism of SK1-induced cell invasion, the levels of FAK phosphorylation, which has been reported to be an important modulator of cellular invasion (36), were assessed in cells expressing scr and SK1 shRNA. As shown in Fig. 5A, SK1 down-regulation was associated with reduced phosphorylation of FAK. In addition, to solidify the role of SK1 in FAK phosphorylation, we next assessed the impact of transfection-mediated up-regulation of the SK1 gene on FAK phosphorylation in 786-0 cells. As shown in Fig. 5B, SK1 up-regulation was associated with increased FAK phosphorylation, with no difference in total FAK protein levels. Next, to further confirm the role of SK1 in FAK phosphorylation, a pharmacological approach was applied by using a nonlipid SK inhibitor, SKi-II (37), as well as an inhibitor for FAK phosphorylation (FAKi) (38) as a positive control. 786-0 cells were treated with DMSO vehicle, FAKi 14 (5 and 10 µM), or SKi-II (5 and 10 µM) for 24 hours. FAK phosphorylation then was examined (Fig. 5C) and found to be decreased in response to inhibition of FAK or SK1. It is worth mentioning that SKi-II has recently been reported to have an off-target effect on ceramide desaturase (39); however, by use of that inhibitor, we observed a similar effect on biology and FAK phosphorylation as shown by knocking down SK1 in ccRCC 786-0 cells. These findings further support the role of SK1, probably through the production of S1P, in inducing FAK phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

SK1 regulates phosphorylation of FAK in 786-0 cells through S1P-S1PR2. A) Protein lysates from scrambled (Scr) and SK1 shRNA stable cells were subjected to Western blot analysis for p-FAK, t-FAK, and β-actin as a loading control. B) 786-0 cells were transfected with either empty vector or SK1-expressing plasmid, followed by Western blot analysis of FAK phosphorylation. C) 786-0 cells were treated with vehicle (V), FAKi (5 and 10 µM), or sphingosine kinase inhibitor, SKi-II (5 and 10 µM final concentrations) for 24 hours followed by protein extraction and Western blotting analysis. Representative blots are shown from 3 independent experiments. D) SK1 shRNA stable cells were serum starved for 6 hours and treated with vehicle or 100 nM S1P for 10 minutes following 1-hour pretreatment with 10 µM from each S1PR2-specific antagonist, JTE-013; S1PR1/3 antagonist, VPC 23019; or S1PR4-specific antagonist, CYM 50358. pFAK, tFAK, and β-actin levels were analyzed by Western blotting. E) SK1 shRNA stable cells were transfected with AllStars negative control or S1PR2 siRNA. Cells were then serum starved and treated with vehicle or S1P for 10 minutes, and FAK phosphorylation was assessed by Western blotting.

Next, to further define the mechanism of SK1 regulation of FAK phosphorylation, pFAK levels were examined in response to S1P treatment. As shown in Fig. 5D, treatment of SK1 shRNA-expressing cells with 100 nM S1P for 10 minutes was sufficient to induce phosphorylation of FAK. We were interested to understand the mechanism by which S1P induces FAK phosphorylation. As S1P can signal either extracellularly through G protein-coupled receptors or intracellularly (40), we evaluated the possible role of S1P receptors in FAK phosphorylation by using pharmacologic antagonists for S1P receptors. Cells were treated with the S1PR1/3 antagonist VPC 23019; the S1PR2-specific antagonist JTE-013; or the S1PR4-specific antagonist CYM 50358. Cells were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle or 10 μM from each S1PR antagonist followed by 10 minutes of S1P treatment. S1P maintained its ability to induce FAK phosphorylation in the presence of the S1PR1/3 and S1PR4 antagonists, indicating that S1PR1, S1PR3, and S1PR4 are not involved in S1P-mediated FAK phosphorylation (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, JTE-013, a specific S1PR2 antagonist, inhibited S1P-stimulated FAK phosphorylation, indicating that S1PR2 plays an important role in FAK phosphorylation in response to S1P. JTE-013 also inhibited S1P-induced FAK phosphorylation in scr shRNA stable cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A). In addition, a similar effect on S1P-induced FAK phosphorylation was observed following S1PR2 knockdown using siRNA (Fig. 5E).

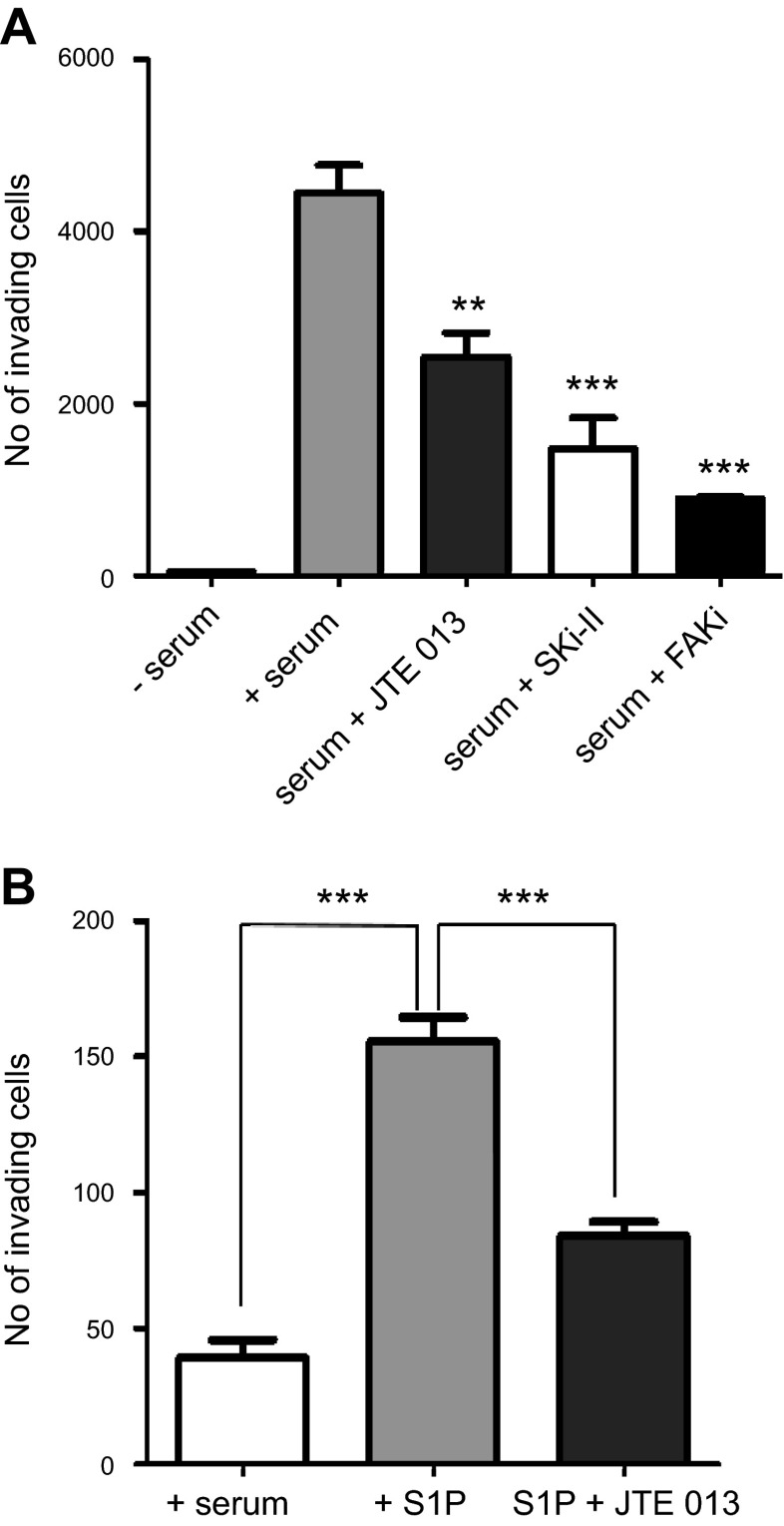

SK1-mediated cell invasion occurs via S1PR2-dependent FAK phosphorylation and a FAK-independent mechanism through S1PR1/3

We showed that FAK phosphorylation in ccRCC cells is dependent on the S1P/S1PR2 axis. Next, we wanted to assess the role of this pathway on cellular invasion. To this end, we used pharmacologic inhibitors against SK1 and S1PR2 to check their effect on cellular invasion. As shown in Fig. 6A, treatment with SK inhibitor and S1PR2 antagonist significantly reduced the cellular invasion toward complete medium (+serum). In addition, treatment of cells with S1P reversed the inhibitory effect of SKi-II on cell invasion (Supplemental Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that SK1/S1PR2 axis is essential for the invasion of ccRCC cells. Furthermore, we wanted to examine whether S1P/S1PR2-mediated cellular invasion is FAK dependent. To this end, we used a pharmacologic inhibitor of FAK phosphorylation and assessed its role in cellular invasion. As shown in Fig. 6A, inhibition of FAK phosphorylation markedly reduced cellular invasion. Therefore, these results suggest that FAK-mediated invasion of ccRCC cells is dependent on the S1P/S1PR2 axis. To further support the role of S1P/S1PR2 axis in invasion of ccRCC cells, SK1 shRNA-expressing cells were allowed to invade toward serum-free medium or serum-free media containing 500 nM S1P in the presence or absence of JTE-013. As shown in Fig. 6B, cells invaded toward serum-free media containing S1P, and this was significantly inhibited by JTE-013, suggesting that S1P activation of FAK could play a role in cellular invasion that is mediated by S1PR2. Moreover, treating cells with the S1PR1/3 antagonist VPC 23019 also decreased the cellular invasion (Supplemental Fig. 1E); however, this effect is not mediated via FAK activation (as shown in Fig. 5D). These data together with the previously presented data provide insight into the mechanism by which SK1/S1P could play an important role in cellular invasion of ccRCC cells through a S1PR2/FAK-dependent mechanism and a FAK-independent mechanism through S1PR1/3.

Figure 6.

S1P receptor 2 antagonist (JTE013), pharmacologic inhibitors of sphingosine kinase (SKi-II) and FAK (FAKi) decreased the invasion of ccRCC cells. A) 786-0 cells stably expressing scrambled shRNA were serum starved in serum-free medium for 4 hours, plated in the apical chamber of Matrigel-coated transwell inserts, treated with 10 μM JTE013, 10 μM SKi-II, or 5 μM FAKi and allowed to invade for 48 hours toward serum. B) 786-0 cells stably expressing SK1 shRNA were serum starved in serum-free medium for 4 hours, plated in the apical chamber of Matrigel-coated transwell inserts with or without 10 μM JTE013, and allowed to invade for 48 hours toward serum-free medium or serum-free with S1P. Invading cells were stained with fluorescent dye and counted. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n ≥ 3.

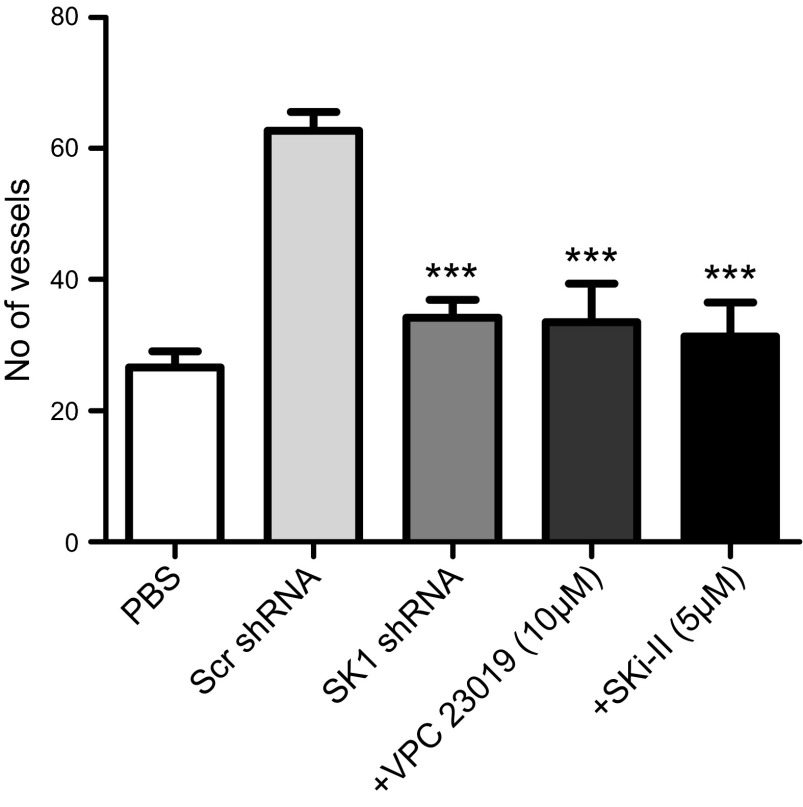

SK1 down-regulation is associated with less angiogenesis in ccRCC 786-0 cells

ccRCC is well known to be an angiogenic tumor (41); moreover, SK1 and S1P have been shown previously to be involved in tumor angiogenesis (42–44). Therefore, we aimed to examine whether SK1 is also involved in the increased angiogenesis of ccRCC using an in vivo CAM assay. CAMs were incubated for 4 days with cells stably expressing scr or SK1 shRNA. To determine whether the effect on angiogenesis by SK1 is due to S1P, we used the S1PR1/3-specific antagonist VPC23019 and the S1PR2 antagonist JTE-013. In addition, a pharmacologic inhibitor of SK, SKi-II, was also used to confirm the role of SK1 in angiogenesis. As shown in Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig. 1F, cells expressing scr shRNA were more angiogenic, as assessed by the number of vessels that grew toward the sponge, than those expressing SK1 shRNA, and their angiogenesis was inhibited by VPC23019 and SKi-II but not by JTE-013. These results suggest that SK1 plays an important role in angiogenesis in VHL-deficient ccRCC cells that is mediated by S1P/S1PR1/3.

Figure 7.

Down-regulation of SK1 expression is associated with less angiogenesis that is also blocked by the S1PR1/3 antagonist and SKi-II. 786-0 cells stably expressing SK1shRNA were incubated with CAM. The same was performed for cells expressing scrambled shRNA with or without 10 µM S1PR1/3 antagonist VPC23019 or inhibitor of sphingosine kinase, SKi-II, for 4 days. The membranes then were photographed, and blood vessels were counted. ***P < 0.001; n = 3.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a novel role of SK1/S1P-induced invasion and angiogenesis of 786-0 ccRCC cells has been identified. First, the data showed that lack of functional VHL in 786-0 ccRCC cells results in higher SK1 expression at both the protein and message level, as well as higher S1P levels, which seem to be HIF-2α dependent. Moreover, S1P treatment of SK1 knockdown cells, which exhibited a less invasive phenotype, resulted in S1PR2-mediated phosphorylation of FAK and invasion. Moreover, down-regulation of SK1 was also associated with less angiogenesis in vivo that appears to be mediated by S1PR1/3. These findings suggest that higher S1P levels in VHL-defective ccRCC could induce invasion and angiogenesis. Together, these results have important implications for the role of the SK1/S1P pathway in the invasion and angiogenesis of ccRCC, which has not been addressed previously.

SK1 has been suggested as a potential therapeutic target as its expression is increased in many cancer types. Previous studies suggested that it plays important roles in proliferation, angiogenesis, survival, and invasion of tumor cells (20, 45). However, its role in ccRCC has not been addressed previously. Therefore, we aimed to study the potential role of SK1 in renal carcinoma. We showed that VHL-defective ccRCC cells showed higher SK1 and S1P levels that seem to be HIF-2α dependent. These results support the previously reported findings by our group that HIF-2α binds to the SK1 promoter, inducing its overexpression during hypoxia in glioma cells (14). We also demonstrated that SK1 is required for activation of FAK through S1P/S1PR2. FAK is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that has been reported to modulate cell migration and invasion (36). Several previous reports have shown that FAK is overexpressed in different tumors such as gastrointestinal and breast cancer and correlated with tumor progression and malignancy (46, 47). Increased FAK activity has been shown previously to be associated with malignancy in different types of cancer cells, suggesting that FAK could play an important role in cancer progression and metastasis (48). Likewise, high pFAK abundance was recently reported to be associated with distant and lymph node metastases in serous ovarian cancer (49). In the mouse model of pancreatic cancer, inhibition of FAK phosphorylation reduced tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis (50). Moreover, suppression of FAK signaling prevented the metastasis of human colon cancer cells (51). Recently, FAK inhibition has been reported to abrogate the invasion of aggressive pediatric renal tumor (52), suggesting that FAK could play a role in invasion of kidney cancer. By studying S1P activation of FAK, we were able to implicate the S1P/S1PR2 pathway in an SK1-mediated invasive biology in ccRCC cells. We showed that SK1 is important for phosphorylation of FAK through a mechanism involving S1P and S1PR2. Previous studies have shown that S1P is able to induce FAK phosphorylation and motility of human endothelial cells (53, 54). However, here we describe the mechanism by which such induction occurs and its implication in invasion biology. Targeting FAK phosphorylation directly by FAK-specific inhibitor or indirectly by SK inhibitor and S1PR2 antagonist significantly reduced the invasion of ccRCC cells, suggesting that SK1-induced FAK activation is important for promoting cellular invasion. Moreover, targeting S1PR1/3 by a specific antagonist also reduced the cellular invasion; however, that effect occurs through a FAK-independent mechanism. It was recently shown that S1PR1 and S1PR2 coordinately mediate S1P-induced migration through activation of different kinase pathways (55).

A link between SK1, FAK, and invasion has been described recently in colon cancer (56). The authors showed that SK1 is involved in the regulation of FAK expression and invasion in colon cancer cells. However, our results clearly demonstrate that SK1 is only required for phosphorylation of FAK and has no effect on the expression of FAK.

S1P has previously been shown to induce the invasion of MCF10A breast cancer cells (57). Moreover, SK/S1P has been implicated in invasive behavior of glioma cells via S1PR2 and up-regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (58). S1PR2 has also recently been shown by our group to mediate epidermal growth factor-induced cellular invasion of HeLa cervical cancer cells (30).

There are multiple lines of evidence that highlight the role of S1P and S1PRs in the induction of cancer cell invasion and migration. However, many of the cancer-promoting roles of the SK/S1P pathway are mediated by S1P receptors other than S1PR2. SK1 has recently been shown to mediate the invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (59) and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through S1PR1 (60). Furthermore, S1PR3 has been reported to mediate invasion of MCF10A breast cancer cells (57).

In contrast, S1PR2 has been shown to prevent migration of hematopoietic stem cells (61) and invasion of cervical cancer cells (62). However, other studies have provided evidence that S1PR2 has a cancer- promoting effect. S1PR2 has been shown to induce the invasion of glioma cells (63, 64) and to mediate EGF-induced invasion of cervical cancer cells (30). The findings presented in the current study provide additional evidence supporting the role of S1PRs in cancer cell invasion through S1P/S1PR2-mediated activation of FAK and a FAK-independent role of S1PR1/3.

Angiogenesis is one of the hallmarks of ccRCC (41), and there is much evidence suggesting that both SK1 and S1P are involved in tumor angiogenesis (42–44). Here we clearly demonstrated that angiogenesis observed in ccRCC is mediated by S1PR1/3. The role of S1P and S1PR in angiogenesis has been shown previously by other reports. S1P has been shown to promote angiogenesis in vivo using Matrigel plug assay (65) and to induce angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in mouse model of breast cancer metastasis (45). The effect of S1P has been shown to be mediated by S1PR1 in vivo (42) and in vitro (14, 43). A previous study by our group reported that the modulation of SK1 expression in glioma and breast cancer cells affected exogenous S1P levels that induce angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in vitro (43).

From our results presented herein, we propose that SK1-generated S1P could have autocrine and paracrine effects in ccRCC. The autocrine effect involves invasion that is mediated by 2 mechanisms: the first involves S1PR2-dependent FAK activation and the other one is S1PR1/3 mediated. Conversely, the paracrine effect involves S1P/S1PR1/3-mediated angiogenesis.

In summary, our data indicate for the first time that SK1 is overexpressed and essential for cellular invasion and angiogenesis of ccRCC cells. Therefore, targeting SK1 could hinder the invasiveness and angiogenesis of ccRCC, thus resulting in improved survival rate of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Science and Technology Development Fund, Egypt, for providing travel funding for M.F.S. The authors thank Dr. Jizu Zhi (Department of Pathology, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, USA) for help with TCGA RNA seq database analysis and Dr. Masayuki Wada and Dr. Jean-Phillip Truman (Stony Brook Medicine) for valuable help and discussions. The authors also thank Dr. Leah Siskind (University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY, USA) for providing shRNA plasmids used for production of lentiviral particles. This work was supported by a U.S. Veterans Affairs Merit Award (to L.M.O.), U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Grant GM062887 (to L.M.O.), NIH National Cancer Institute Grants P01CA097132 (to L.M.O. and Y.A.H.) and F31CA186547-01 (to B.L.C.), and NIH NIGMS Training Grant T32 GM007518 (M.P.G.). Lipid analyses were provided by the Lipidomics Core Facility at Stony Brook University.

Glossary

- C17-Sph

d-erythro-17-carbon sphingosine

- CAM

chorioallantoic membrane

- ccRCC

clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- CT

cycle threshold

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FAKi

FAK inhibitor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- MTT

3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- pFAK

phospho-focal adhesion kinase

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- S1PR

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor

- scr

scrambled

- shRNA

short-hairpin RNA

- SK1/2

sphingosine kinase 1/2

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rini B. I., Campbell S. C., Escudier B. (2009) Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 373, 1119–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gnarra J. R., Tory K., Weng Y., Schmidt L., Wei M. H., Li H., Latif F., Liu S., Chen F., Duh F. M., et al. (1994) Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in renal carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 7, 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schraml P., Struckmann K., Hatz F., Sonnet S., Kully C., Gasser T., Sauter G., Mihatsch M. J., Moch H. (2002) VHL mutations and their correlation with tumour cell proliferation, microvessel density, and patient prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Pathol. 196, 186–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman J. G., Latif F., Weng Y., Lerman M. I., Zbar B., Liu S., Samid D., Duan D. S., Gnarra J. R., Linehan W. M., et al. (1994) Silencing of the VHL tumor-suppressor gene by DNA methylation in renal carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9700–9704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell P. H., Wiesener M. S., Chang G. W., Clifford S. C., Vaux E. C., Cockman M. E., Wykoff C. C., Pugh C. W., Maher E. R., Ratcliffe P. J. (1999) The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399, 271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cockman M. E., Masson N., Mole D. R., Jaakkola P., Chang G. W., Clifford S. C., Maher E. R., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Maxwell P. H. (2000) Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25733–25741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keith B., Johnson R. S., Simon M. C. (2012) HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo K., Kim W. Y., Lechpammer M., Kaelin W. G. Jr (2003) Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol. 1, E83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raval R. R., Lau K. W., Tran M. G. B., Sowter H. M., Mandriota S. J., Li J.-L., Pugh C. W., Maxwell P. H., Harris A. L., Ratcliffe P. J. (2005) Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5675–5686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmer M., Doucette D., Siddiqui N., Iliopoulos O. (2004) Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor is sufficient for growth suppression of VHL-/- tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2, 89–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu C.-J., Wang L.-Y., Chodosh L. A., Keith B., Simon M. C. (2003) Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 9361–9374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang V., Davis D. A., Haque M., Huang L. E., Yarchoan R. (2005) Differential gene up-regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in HEK293T cells. Cancer Res. 65, 3299–3306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordan J. D., Bertout J. A., Hu C.-J., Diehl J. A., Simon M. C. (2007) HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer Cell 11, 335–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anelli V., Gault C. R., Cheng A. B., Obeid L. M. (2008) Sphingosine kinase 1 is up-regulated during hypoxia in U87MG glioma cells. Role of hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3365–3375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitson S. M., D’andrea R. J., Vandeleur L., Moretti P. A., Xia P., Gamble J. R., Vadas M. A., Wattenberg B. W. (2000) Human sphingosine kinase: purification, molecular cloning and characterization of the native and recombinant enzymes. Biochem. J. 350, 429–441 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H., Sugiura M., Nava V. E., Edsall L. C., Kono K., Poulton S., Milstien S., Kohama T., Spiegel S. (2000) Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel mammalian sphingosine kinase type 2 isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19513–19520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wattenberg B. W. (2010) Role of sphingosine kinase localization in sphingolipid signaling. World J. Biol. Chem. 1, 362–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orr Gandy K. A., Obeid L. M. (2013) Targeting the sphingosine kinase/sphingosine 1-phosphate pathway in disease: review of sphingosine kinase inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831, 157–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taha T. A., Kitatani K., El-Alwani M., Bielawski J., Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2006) Loss of sphingosine kinase-1 activates the intrinsic pathway of programmed cell death: modulation of sphingolipid levels and the induction of apoptosis. FASEB J. 20, 482–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2008) Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chumanevich A. A., Poudyal D., Cui X., Davis T., Wood P. A., Smith C. D., Hofseth L. J. (2010) Suppression of colitis-driven colon cancer in mice by a novel small molecule inhibitor of sphingosine kinase. Carcinogenesis 31, 1787–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao P., Smith C. D. (2011) Ablation of sphingosine kinase-2 inhibits tumor cell proliferation and migration. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 1509–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siow D., Wattenberg B. (2011) The compartmentalization and translocation of the sphingosine kinases: mechanisms and functions in cell signaling and sphingolipid metabolism. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 46, 365–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruckhäberle E., Rody A., Engels K., Gaetje R., von Minckwitz G., Schiffmann S., Grösch S., Geisslinger G., Holtrich U., Karn T., Kaufmann M. (2008) Microarray analysis of altered sphingolipid metabolism reveals prognostic significance of sphingosine kinase 1 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 112, 41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson K. R., Johnson K. Y., Crellin H. G., Ogretmen B., Boylan A. M., Harley R. A., Obeid L. M. (2005) Immunohistochemical distribution of sphingosine kinase 1 in normal and tumor lung tissue. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 53, 1159–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhuge Y. H., Tao H. Q., Wang Y. Y. (2011) [Relationship between sphingosine kinase 1 expression and tumor invasion, metastasis and prognosis in gastric cancer]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 91, 2765–2768 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan H., Liu L., Cai J., Liu J., Ye C., Li M., Li Y. (2011) Sphingosine kinase 1 is overexpressed and promotes proliferation in human thyroid cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 1858–1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Facchinetti M. M., Gandini N. A., Fermento M. E., Sterin-Speziale N. B., Ji Y., Patel V., Gutkind J. S., Rivadulla M. G., Curino A. C. (2010) The expression of sphingosine kinase-1 in head and neck carcinoma. Cells Tissues Organs (Print) 192, 314–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamori T., Osta W., Johnson K. R., Pettus B. J., Bielawski J., Tanaka T., Wargovich M. J., Reddy B. S., Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M., Zhou D. (2006) Sphingosine kinase 1 is up-regulated in colon carcinogenesis. FASEB J. 20, 386–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orr Gandy K. A., Adada M., Canals D., Carroll B., Roddy P., Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2013) Epidermal growth factor-induced cellular invasion requires sphingosine-1-phosphate/sphingosine-1-phosphate 2 receptor-mediated ezrin activation. FASEB J. 27, 3155–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitatani K., Idkowiak-Baldys J., Hannun Y. A. (2007) Mechanism of inhibition of sequestration of protein kinase C alpha/betaII by ceramide. Roles of ceramide-activated protein phosphatases and phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of protein kinase C alpha/betaII on threonine 638/641. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20647–20656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Veldhoven P. P., Bell R. M. (1988) Effect of harvesting methods, growth conditions and growth phase on diacylglycerol levels in cultured human adherent cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 959, 185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohno M., Momoi M., Oo M. L., Paik J. H., Lee Y. M., Venkataraman K., Ai Y., Ristimaki A. P., Fyrst H., Sano H., Rosenberg D., Saba J. D., Proia R. L., Hla T. (2006) Intracellular role for sphingosine kinase 1 in intestinal adenoma cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 7211–7223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vadas M., Xia P., McCaughan G., Gamble J. (2008) The role of sphingosine kinase 1 in cancer: Oncogene or non-oncogene addiction? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1781, 442–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwock J., Dhani N., Hedley D. W. (2010) Targeting focal adhesion kinase signaling in tumor growth and metastasis. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 14, 77–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.French K. J., Schrecengost R. S., Lee B. D., Zhuang Y., Smith S. N., Eberly J. L., Yun J. K., Smith C. D. (2003) Discovery and evaluation of inhibitors of human sphingosine kinase. Cancer Res. 63, 5962–5969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golubovskaya V. M., Nyberg C., Zheng M., Kweh F., Magis A., Ostrov D., Cance W. G. (2008) A small molecule inhibitor, 1,2,4,5-benzenetetraamine tetrahydrochloride, targeting the y397 site of focal adhesion kinase decreases tumor growth. J. Med. Chem. 51, 7405–7416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cingolani F., Casasampere M., Sanllehí P., Casas J., Bujons J., Fabrias G. (2014) Inhibition of dihydroceramide desaturase activity by the sphingosine kinase inhibitor SKI II. J. Lipid Res. 55, 1711–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tolan D., Conway A. M., Rakhit S., Pyne N., Pyne S. (1999) Assessment of the extracellular and intracellular actions of sphingosine 1-phosphate by using the p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade as a model. Cell. Signal. 11, 349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldewijns M. M., van Vlodrop I. J., Vermeulen P. B., Soetekouw P. M., van Engeland M., de Bruïne A. P. (2010) VHL and HIF signalling in renal cell carcinogenesis. J. Pathol. 221, 125–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chae S.-S., Paik J.-H., Furneaux H., Hla T. (2004) Requirement for sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 in tumor angiogenesis demonstrated by in vivo RNA interference. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1082–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anelli V., Gault C. R., Snider A. J., Obeid L. M. (2010) Role of sphingosine kinase-1 in paracrine/transcellular angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in vitro. FASEB J. 24, 2727–2738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pitson S. M., Powell J. A., Bonder C. S. (2011) Regulation of sphingosine kinase in hematological malignancies and other cancers. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 11, 799–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagahashi M., Ramachandran S., Kim E. Y., Allegood J. C., Rashid O. M., Yamada A., Zhao R., Milstien S., Zhou H., Spiegel S., Takabe K. (2012) Sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase 1 promotes breast cancer progression by stimulating angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Cancer Res. 72, 726–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lahlou H., Sanguin-Gendreau V., Zuo D., Cardiff R. D., McLean G. W., Frame M. C., Muller W. J. (2007) Mammary epithelial-specific disruption of the focal adhesion kinase blocks mammary tumor progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 20302–20307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao H.-F., Naomoto Y., Bao X.-H., Watanabe N., Sakurama K., Noma K., Tomono Y., Fukazawa T., Shirakawa Y., Yamatsuji T., Matsuoka J., Takaoka M. (2009) Progress in researches about focal adhesion kinase in gastrointestinal tract. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 5916–5923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao H., Naomoto Y., Bao X., Watanabe N., Sakurama K., Noma K., Motoki T., Tomono Y., Fukazawa T., Shirakawa Y., Yamatsuji T., Matsuoka J., Wang Z. G., Takaoka M. (2009) Focal adhesion kinase as potential target for cancer therapy (Review). [Review] Oncol. Rep. 22, 973–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aust S., Auer K., Bachmayr-Heyda A., Denkert C., Sehouli J., Braicu I., Mahner S., Lambrechts S., Vergote I., Grimm C., Horvat R., Castillo-Tong D. C., Zeillinger R., Pils D. (2014) Ambivalent role of pFAK-Y397 in serous ovarian cancer—a study of the OVCAD consortium. Mol. Cancer 13, 67–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stokes J. B., Adair S. J., Slack-Davis J. K., Walters D. M., Tilghman R. W., Hershey E. D., Lowrey B., Thomas K. S., Bouton A. H., Hwang R. F., Stelow E. B., Parsons J. T., Bauer T. W. (2011) Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase by PF-562,271 inhibits the growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer concomitant with altering the tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 2135–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dia V. P., Gonzalez de Mejia E. (2011) Lunasin potentiates the effect of oxaliplatin preventing outgrowth of colon cancer metastasis, binds to α5β1 integrin and suppresses FAK/ERK/NF-κB signaling. Cancer Lett. 313, 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Megison M. L., Gillory L. A., Stewart J. E., Nabers H. C., Mrozcek-Musulman E., Beierle E. A. (2014) FAK inhibition abrogates the malignant phenotype in aggressive pediatric renal tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 12, 514–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee O. H., Lee D. J., Kim Y. M., Kim Y. S., Kwon H. J., Kim K. W., Kwon Y. G. (2000) Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and chemotactic motility of endothelial cells via the G(i) protein-linked phospholipase C pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268, 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao J., Singleton P. A., Brown M. E., Dudek S. M., Garcia J. G. N. (2009) Phosphotyrosine protein dynamics in cell membrane rafts of sphingosine-1-phosphate-stimulated human endothelium: role in barrier enhancement. Cell. Signal. 21, 1945–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quint P., Ruan M., Pederson L., Kassem M., Westendorf J. J., Khosla S., Oursler M. J. (2013) Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptors 1 and 2 coordinately induce mesenchymal cell migration through S1P activation of complementary kinase pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5398–5406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu S.-Q., Su Y.-J., Qin M.-B., Mao Y.-B., Huang J.-A., Tang G.-D. (2013) Sphingosine kinase 1 promotes tumor progression and confers malignancy phenotypes of colon cancer by regulating the focal adhesion kinase pathway and adhesion molecules. Int. J. Oncol. 42, 617–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S., Han J., Kim J. S., Kim J.-H., Choe J.-H., Yang J.-H., Nam S. J., Lee J. E. (2011) Silibinin suppresses EGFR ligand-induced CD44 expression through inhibition of EGFR activity in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 31, 3767–3773 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young N., Pearl D. K., Van Brocklyn J. R. (2009) Sphingosine-1-phosphate regulates glioblastoma cell invasiveness through the urokinase plasminogen activator system and CCN1/Cyr61. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 23–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamashiro P. M., Furuya H., Shimizu Y., Kawamori T. (2014) Sphingosine kinase 1 mediates head & neck squamous cell carcinoma invasion through sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1. Cancer Cell Int. 14, 76–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bao M., Chen Z., Xu Y., Zhao Y., Zha R., Huang S., Liu L., Chen T., Li J., Tu H., He X. (2012) Sphingosine kinase 1 promotes tumour cell migration and invasion via the S1P/EDG1 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 32, 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donati C., Nincheri P., Cencetti F., Rapizzi E., Farnararo M., Bruni P. (2007) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha exerts pro-myogenic action in C2C12 myoblasts via sphingosine kinase/S1P2 signaling. FEBS Lett. 581, 4384–4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gandy K. A., Canals D., Adada M., Wada M., Roddy P., Snider A. J., Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2013) Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces filopodia formation through S1PR2 activation of ERM proteins. Biochem. J. 449, 661–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Brocklyn J., Letterle C., Snyder P., Prior T. (2002) Sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates human glioma cell proliferation through Gi-coupled receptors: role of ERK MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta. Cancer Lett. 181, 195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Brocklyn J. R., Jackson C. A., Pearl D. K., Kotur M. S., Snyder P. J., Prior T. W. (2005) Sphingosine kinase-1 expression correlates with poor survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme: roles of sphingosine kinase isoforms in growth of glioblastoma cell lines. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 64, 695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee O. H., Kim Y. M., Lee Y. M., Moon E. J., Lee D. J., Kim J. H., Kim K. W., Kwon Y. G. (1999) Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces angiogenesis: its angiogenic action and signaling mechanism in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 264, 743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.