Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Patient satisfaction after anesthesia is an important outcome of hospital care. The aim is to evaluate the postoperative patient satisfaction during the patient stay at King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Patients and Methods:

Three hundred and fifty-three patients who underwent surgery under general/regional anesthesia were surveyed. They were interviewed face to face on the first postoperative day. We recorded pain and pain controls in addition to some common complication of anesthesia like nausea and vomiting (postoperative nausea and vomiting) as a parameter to assess the rate of patient's satisfaction.

Results:

The overall level of satisfaction was high (95.2%); 17 (4.8%) patients were dissatisfied with their anesthetic care. There was a strong relation between patient dissatisfaction and: (i) Patients with poor postoperative pain control 13 (12.4%), (ii) patients with moderate nausea 8 (11.1%) and (iii) patients with static and dynamic severe pain 6 (21.4). Several factors were associated with dissatisfaction can be prevented, or better treated.

Conclusion:

We concluded that the patient satisfaction was high. Postoperative visit should be routinely performed in order to assess the quality and severity of postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting and the other side-effects postoperatively.

Keywords: Anesthesia, nausea and vomiting, pain, patient satisfaction, postoperative complications

INTRODUCTION

The quality of health care has been defined as the degree to which health services increase the likelihood of desired health outcome consistent with current professional knowledge. Patient satisfaction is an important measure of quality of care that can contribute to a balanced evaluation of the structure, process and outcome of service.[1,2,3]

Case studies using local survey data can be used as formative assessments of services. The response rate to the survey and the likelihood of responder bias mean that patient satisfaction survey data of this sort cannot be used to judge or compare services in a summative way, but can highlight areas where remedial action is needed. Small-scale local surveys may seem to lack the robustness of larger studies, but do identify similar areas of concern. Commissioners and clinicians could use the findings of such surveys to inform dialogues about the quality of hospital care for older people.[4]

Increasing awareness that the value of health care services has made patient-reported outcomes, including assessments of the experience of health care, a key basis of comparison for services delivered by physicians, health plans, and hospital systems.[5,6] Although anesthesiologists have worked for at least 40 years to develop objective measures of patient satisfaction with anesthesia care, the lack of uniformly accepted methods for the assessment of patient experience in the perioperative setting leaves important gaps in knowledge as to how anesthesia care may be improved.[7,8] There are few studies in anesthesia that have assessed patient satisfaction, and most are restricted to day-case surgical patients.[9,10]

The aim of this survey is to evaluate the postoperative patient satisfaction during the patient stay at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

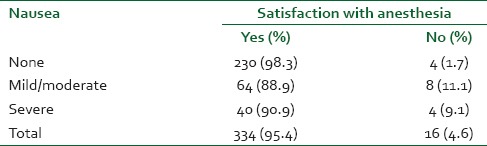

After approval of the Departmental and Hospital Research Review Boards, an informed written consent was taken from the patients before being enrolled in the study. A cross-sectional study with a random sampling technique aiming to assess the satisfaction of the postoperative patients (number 353, 162 males) who underwent regional and general anesthesia at KKUH. The mean age was 40.2 years. In this study, we include both gender male and female, older than 10 years, interviewed during the first 24 h after surgery. We excluded patients admitted to surgical intensive care unit (ICU) postoperatively. Data collection tool included: Patient characteristics (age, sex, etc.), type of anesthesia and type of surgery. Postoperative health side effects, satisfaction of the patients, what has been done to solve the dissatisfaction were recorded. Pain control was rated on an ordinal scale and then dichotomized as: (1 = Good or excellent, 0 = adequate or poor control), nausea and vomiting was rated on an ordinal scale and then dichotomized as: (0 = No nausea and vomiting or 1 = mild nausea, 2 = severe nausea and vomiting). Other postoperative complications (nausea, vomiting, dizziness, sleepiness, sore throat, awareness during anesthesia, muscle pain, headache) were also recorded. We calculated the sample size with this equation  and with confidence level: 95%, width of confident interval: ± 5.5% assuming P = 35%. The data were entered to Microsoft Office Excel 2010 file by the participants then imported to SPSS statistics 17.0 for analysis (USA).

and with confidence level: 95%, width of confident interval: ± 5.5% assuming P = 35%. The data were entered to Microsoft Office Excel 2010 file by the participants then imported to SPSS statistics 17.0 for analysis (USA).

RESULTS

The response rate was 100% (353 patients). Three hundred and twenty-one patients received general anesthesia, and 32 patients received regional anesthesia. The overall level of satisfaction was 95.2%. Patients who were dissatisfied with their anesthesia care represent 4.8% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient satisfaction with anesthesia

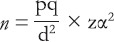

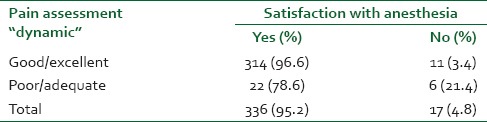

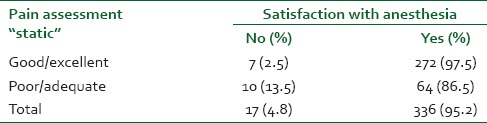

There was a strong relation between dissatisfaction and poor postoperative pain control [Table 2], nausea [Table 3].

Table 2.

Pain assessment

Table 3.

Incidence of nausea

DISCUSSION

We found a high rate satisfaction with anesthesia care in patients interviewed on the 1st day after surgery. The rate of dissatisfaction was low. However, it is recognized that the patient satisfaction depends on pain control, nausea and vomiting. Other hospital satisfaction surveys have reported dissatisfaction rates of <15%.[9,10,11,12] It has been suggested previously that patients usually do not know what to expect during their hospitalization to be able to rate their satisfaction level.[5] Dissatisfaction with anesthesia, as we mentioned, is associated with the quality of the pain control, 12.4% with poor pain control were dissatisfied (P < 0.0005). Furthermore, we found out that (4.6%) of patients with nausea were dissatisfied, 11.1% of them suffered from mild nausea and 9.1% suffered from severe nausea (P < 0.0005). Patients with higher score on the pain scale “dynamic and static” are associated with dissatisfaction, 21.4% with high score in the dynamic pain scale are dissatisfied and 13.5% of patients who scored high in the static pain scale also were dissatisfied. It is possible that our results were affected by reporting or detection bias in that patients unable cooperate may have lower satisfaction rate. We believe this is unlikely as these patients were generally older and sicker, and they are usually in the ICU or recovering from extensive surgery. The risk of dissatisfaction increased as the adverse events after the anesthesia, these adverse events included moderate or severe pain and severe nausea and vomiting, we found that awareness during anesthesia is rare. In our study, we surveyed 353 patients which is low in comparison to some other studies but still statistically enough, also the type of surgery was not included in our study. This study can be modified in future according to the type of anesthesia. In conclusion, we surveyed 353 patients in the first 24 h after anesthesia, the major subjective outcome measure was patient satisfaction, also measured other predetermined outcomes, such as nausea, vomiting, pain and complications. The overall level of satisfaction was high 336 (95.2%), 17 (4.8%) were “dissatisfied” with their anesthetic care. There was a strong relation between patient dissatisfaction and with the quality of the pain control, 12.4% with poor pain control were dissatisfied, (4.6%) of patents with nausea were dissatisfied, 21.4% with high score in the dynamic pain scale are dissatisfied and 13.5% of patients who scored high in the static pain scale also were dissatisfied. Pain control after surgery and anesthesia should be improved by pain unit at the hospital by visiting the patients after surgery to assess the pain and control it safely and immediately, nausea and vomiting control should be improved by assessment and treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Myles PS, Williams DL, Hendrata M, Anderson H, Weeks AM. Patient satisfaction after anesthesia and surgery: Results of a prospective survey of 10,811 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:6–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA. 1994;272:619–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westbrook JI. Patient satisfaction: Methodological issues and research findings. Aust Health Rev. 1993;16:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lliffe S, Wilcock J, Manthorpe J, Moriarty J, Cornes M, Clough R, et al. Can clinicians benefit from patient satisfaction surveys? Evaluating the NSF for Older People, 2005-2006. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:598–604. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2477–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu AW, Snyder C, Clancy CM, Steinwachs DM. Adding the patient perspective to comparative effectiveness research. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1863–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung D, Cohen MM. Measuring patient satisfaction with anesthesia care: A review of current methodology. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1089–98. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199811000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuman MD. Patient satisfaction and value in anesthesia care. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1019–20. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318216ea25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong D, Chung F, Wong D. Predictive factors in global and anesthesia satisfaction in ambulatory surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:856–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pineault R, Contandriopoulos AP, Valois M, Bastian ML, Lance JM. Randomized clinical trial of one-day surgery. Patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and costs. Med Care. 1985;23:171–82. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward SE, Gordon D. Application of the American Pain Society quality assurance standards. Pain. 1994;56:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzpatrick R. Surveys of patient satisfaction: II — Designing a questionnaire and conducting a survey. BMJ. 1991;302:1129–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]