Our results show that sub-optimal inhibition of MEK in combination with AKT is less efficient in inhibiting cellular growth compared to completely inhibiting MEK and AKT alone. The results also show that KRAS mutant cells are more sensitive to a combination of MEK and AKT inhibitors compared to BRAF and PIK3CA mutant cells. Both these findings have clinical implications.

Keywords: combination, MEK inhibitor, AKT inhibitor

Abstract

Background

We aimed to understand the relative contributions of inhibiting MEK and AKT on cell growth to guide combinations of these agents.

Materials and methods

A panel of 20 cell lines was exposed to either the MEK inhibitor, PD0325901, or AKT inhibitor, AKT 1/2 inhibitor. p-ERK and p-S6 ELISAs were used to define degrees of MEK and AKT inhibition, respectively. Growth inhibition to different degrees of MEK and AKT inhibition, either singly or in combination using 96-h sulphorhodamine assays was then studied.

Results

A significantly greater growth inhibition was seen in BRAFM and PIK3CAM cells upon maximal MEK (P = 0.004) and AKT inhibition (P = 0.038), respectively. KRASM and BRAF/PIK3CA/KRASWT cells were not significantly more likely to be sensitive to MEK or AKT inhibition. Significant incremental growth inhibition of the combination of MEK + AKT over either MEK or AKT inhibition alone was seen when MEK + AKT was inhibited maximally and not when sub-maximal inhibition of both MEK + AKT was used (11/20 cell lines versus 1/20 cell lines; P = 0.0012).

Conclusions

KRASM cells are likely to benefit from combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors. Sub-maximally inhibiting both MEK and AKT within a combination, in a majority of instances, does not significantly increase growth inhibition compared with maximally inhibiting MEK or AKT alone and alternative phase I trial designs are needed to clinically evaluate such combinations.

introduction

MEK and AKT are important nodes in signal transduction pathways critical to growth and function of cancer cells and normal tissue (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Early clinical studies of MEK and AKT inhibitors have shown that it is possible to achieve therapeutic drug levels and modulate the respective targets [1–6]. Combining MEK and AKT inhibitors for the treatment of cancer is of interest for multiple reasons. First, inhibition of either MEK and AKT would only partially inhibit signalling output, resulting in sub-optimal growth inhibition of cancer cells [7]. Secondly, in defined models, pharmacological inhibition of MEK causes an increase in signalling through AKT [8, 9]. Thirdly, there is growing evidence of intra-tumoral heterogeneity within cancers [10] and this could lead to areas of a tumour that are differentially sensitive to an MEK or AKT inhibitor alone. There is pre-clinical evidence of the activity of MEK inhibitor + AKT inhibitor combinations [11] and, more generally, of drugs inhibiting the RAS-RAF-MEK and PI3K-AKT-m-TOR axis [12–14]. Early clinical activity of these combinations has been demonstrated [15, 16] and combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors have now entered biomarker integrated targeted therapy studies such as BATTLE-2 (NCT-01248247), which uses an adaptive randomization design to use the combination in the setting of non-small-cell lung cancer.

The individual toxicities of MEK and AKT inhibitors are now fairly well defined, with ocular toxicities being limited to MEK inhibitors [1–3] and hyperglycaemia limited to AKT inhibitors [4, 6, 17, 18]. Overlapping toxicities include rash and diarrhoea [1–4, 6, 17, 18]. Thus, there are considerable challenges in combining these agents [16]. It is possible to circumvent such toxicities by altering the scheduling of both agents [19].

Over-arching questions that govern combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors are: (i) which tumours are susceptible to combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors; (ii) is combined maximal inhibition of MEK or AKT better than maximal MEK or AKT inhibition alone; (iii) does sub-optimally inhibiting signalling due to overlapping toxicity compromise the chances of success of combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors? We aimed to answer these three questions in pre-clinical models.

materials and methods

cell lines

Source, authentication, mutations and tissue of origin of cell lines are documented in the supplementary Data and Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Details of the drugs used and ELISAs carried out to quantify inhibition of signalling are in the supplementary Data, available at Annals of Oncology online.

definition of inhibition of MEK and AKT

ELISA readings were normalized to the DMSO control being assessed as 0% and the maximal inhibition of signalling output achieved as 100%. The drug concentration required to cause 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% of maximal reduction of p-S6 or p-ERK levels was then calculated. GraphPad Prism (v6.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for the analysis. 100%, 75%, 50%, 25% inhibition of MEK was defined as maximal reduction in levels of p-ERK or 75%, 50%, 25% of maximal reduction of levels of p-ERK. 100%, 75%, 50%, 25% inhibition of AKT was defined as maximal reduction in levels of p-S6 or 75%, 50%, 25% of maximal reduction of levels of p-S6.

growth inhibition assays

Each of the 20 cell lines was exposed for 96 h to concentrations of PD0325901 and AKT 1/2 kinase inhibitor to inhibit signalling of p-S6 and p-ERK by different degrees, as specified in each experiment. Growth inhibition was calculated using sulphorhodamine assays, as described previously [20]. A similar experiment was done in one randomly chosen cell line from each group (BRAFM, PIK3CAM, KRASM and BRAF/PIK3CA/KRASWT) using a clinically used MEK inhibitor (AZD6244) and AKT inhibitor (AZD5363).

statistical analysis

Differences between growth inhibition upon being exposed to concentrations that maximally inhibited MEK and AKT in a given cell line were analysed using a t-test. A one-way ANOVA was carried out to detect differences between maximal growth inhibition caused by inhibiting MEK by 100% and combinations such as inhibition of MEK 100% + AKT 25%, MEK 100% + AKT 50%, MEK 100% + AKT 25% and MEK 100% + AKT 100%. Post hoc Dunnett's tests were carried out only if the ANOVA showed a significant difference. Similar analysis was carried out while testing differences between growth inhibition caused by 100% AKT inhibition and combinations of 100% AKT inhibition and increasing concentrations of MEK inhibition. A one-way ANOVA was also conducted to detect differences between 100% MEK or AKT inhibition and sub-optimal combinations of MEK and AKT, post hoc Dunnett's tests were carried out only if the ANOVA showed a significant difference. Differences between the number of cell lines categorized by mutation or degrees of inhibition were carried out using Fisher's exact test. GraphPad Prism (v6.0, GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used for the analysis.

results

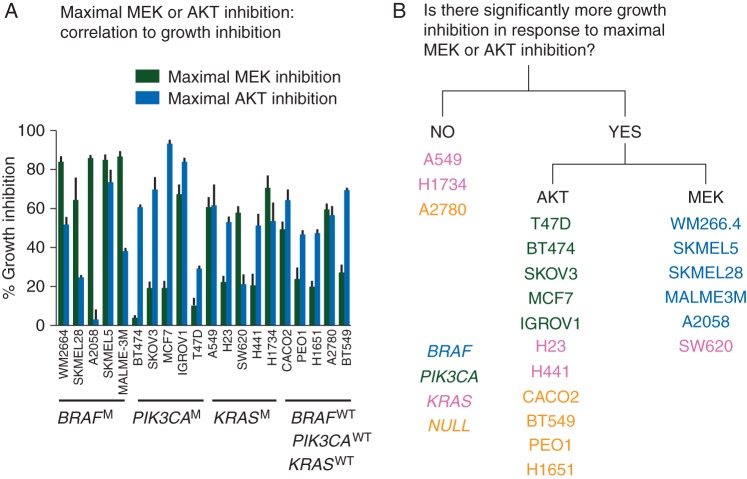

A panel of 20 cell lines (5 BRAFM, 5 PIK3CAM, 5 KRASM, 5 BRAF/PIK3CA/KRASWT), was exposed to a concentration of PD0325901 and AKT1/2 kinase inhibitor that caused maximal MEK and AKT inhibition, respectively, for 96 h and growth inhibition compared with a DMSO-treated control was analysed (Figure 1A) . The ED50 concentrations of PD0325901 and AKT 1/2 kinase inhibitors to inhibit MEK and AKT are documented in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Six of 17 cell lines showed more significantly greater growth inhibition upon maximal MEK inhibition compared with maximal AKT inhibition and 11/17 showed significantly greater inhibition upon maximal AKT inhibition compared with maximal MEK inhibition. Three cell lines were equally sensitive to maximal MEK and AKT inhibition (Figure 1B). BRAFM and PIK3CAM cells were more sensitive to growth inhibition by maximal MEK inhibition; P = 0.0004 and maximal AKT inhibition; P = 0.038, respectively. KRASM and BRAF/PIK3CA/KRASWT cells were not significantly more likely to be sensitive to MEK or AKT inhibition.

Figure 1.

Dependence of growth inhibition on maximal inhibition of signalling output. A panel of 20 cell lines was exposed to concentrations of PD0325901 and AKT1/2 kinase inhibitor which caused maximal MEK and AKT inhibition, respectively, for 96 h. (A) The percentage growth inhibition in cell lines caused by maximal MEK and AKT inhibition. The black (green online) columns represent growth inhibition caused by maximal MEK inhibition and the grey (blue online) columns represent growth inhibition caused by maximal AKT inhibition; (B) the cell lines were classified according to the presence or absence of a statistical difference between maximal MEK and AKT inhibition.

Four cell lines, i.e. SKMEL-28 (BRAFM), T47D (PIK3CAM), A549 (KRASM) and A2780 (BRAF/PIK3CA/KRASWT), were exposed to a clinically used MEK inhibitor (AZD6244) and AKT inhibitor (AZD5363) that caused maximal MEK and AKT inhibition, respectively, and this caused growth inhibitory patterns similar to that caused by PD0325901 and AKT 1/2 kinase inhibitor (supplementary Data, available at Annals of Oncology online). This suggests that the growth inhibitory patterns seen of PD0325901 and AKT 1/2 kinase inhibitor unlikely to be due to off target effects.

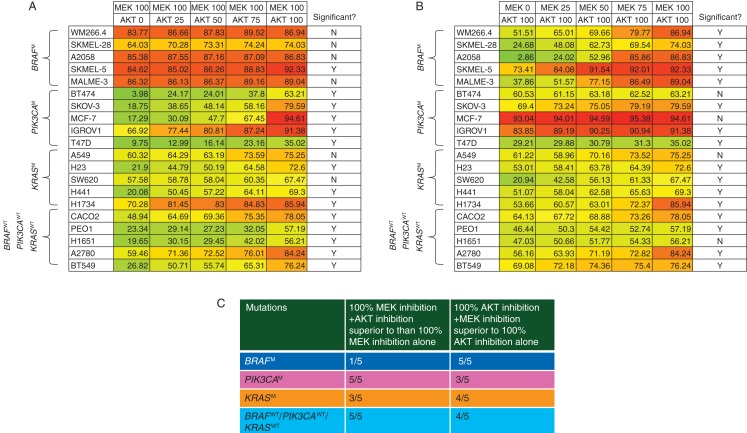

The panel of cell lines was then exposed to maximal inhibition of MEK, in addition to increasing degrees of AKT inhibition (i.e. 25%, 50%, 75% and 100%) (Figure 2A). Only 1/5 BRAFM cells had incremental growth inhibition by the addition of AKT inhibition to the maximal MEK inhibition. The panel of cells was also exposed to maximal inhibition of AKT in addition to increasing degrees of MEK inhibition (i.e. 25%, 50%, 75% and 100%) (Figure 2B). Of the PIK3CAM lines, 3/5 cell lines showed significant incremental benefit of the addition of MEK inhibition to maximal AKT inhibition. The findings are summarized in Figure 2C. In the 20 cell line panel studied, maximal MEK + AKT inhibition caused greater growth inhibition than maximal inhibition than either maximal MEK or maximal AKT in 11/20 cell lines.

Figure 2.

Percentage growth inhibition caused by combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors. Cell lines were exposed to combinations of concentrations of PD0325901 and AKT1/2 kinase inhibitor at which different degrees of MEK and AKT inhibition occurred for 96 h. A one-way ANOVA was carried out to detect differences between growth inhibition caused by maximal MEK or AKT inhibition alone compared with combinations. Post hoc Dunnett's test was only carried out if the ANOVA showed a significant difference. (A) Cell lines exposed to 100% MEK inhibition and increasing levels of AKT inhibition; (B) cell lines exposed to 100% AKT inhibition and increasing levels of MEK inhibition. (C) A summary of numbers of cell lines where there was significantly greater growth inhibition caused by the combinations of MEK + AKT over that caused by maximal inhibition of MEK or AKT alone.

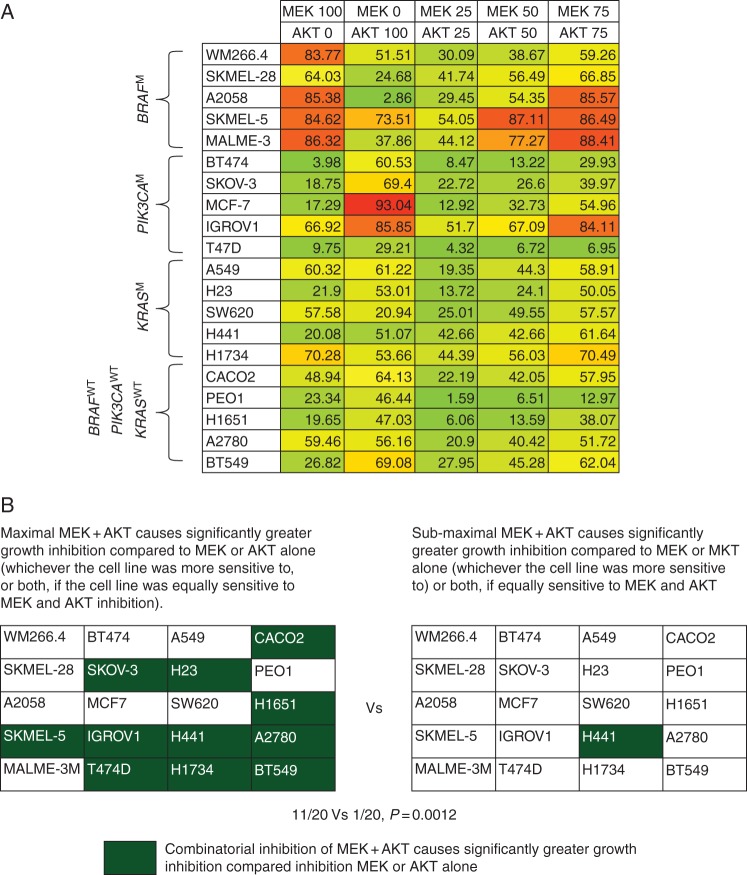

Next, the panel was exposed to different combinations of sub-maximal inhibition of MEK + AKT (25% + 25%, 50% + 50% and 75% + 75%) (Figure 3A). Only 1/20 cell lines showed significantly greater growth inhibition upon sub-maximal inhibition of MEK + AKT compared with either maximal MEK or maximal AKT inhibition.

Figure 3.

Percentage growth inhibition caused by combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors: Effects of sub-maximal inhibition. Cell lines were exposed to combinations of concentrations of PD0325901 and AKT1/2 kinase inhibitor at which different degrees of MEK inhibition and AKT inhibition occurred for 96 h. (A) Cell lines were exposed to 100% MEK inhibition, 100% AKT inhibition or different combinations of sub-maximal MEK + AKT inhibition. (B) A summary of the number of cell lines where the maximal and sub-maximal combinations of MEK + AKT caused significantly greater growth inhibition compared with MEK or AKT inhibition alone (whichever the cell line was more sensitive to, or both, if the cell line was equally sensitive to MEK and AKT inhibition).

Thus, in the cell line panel studied, in 11/20 cell lines, maximal MEK + AKT inhibition caused significantly greater growth inhibition compared with maximal inhibition cause by singly inhibiting MEK or AKT; however, a sub-maximal inhibition of MEK + AKT caused superior growth inhibition caused by singly maximally inhibiting MEK or AKT in only 1/20 cell lines; P = 0.0012 (Figure 3B).

Interestingly, in both HUVEC and Ker-CT cells (representing non-cancer ‘normal’ cells) sub-optimal inhibition of MEK or AKT did not cause significantly more growth inhibition compared with maximal AKT or MEK inhibition alone (whichever the cell line was sensitive to, or both, if the cell line was sensitive to both if the cell line was equally sensitive to MEK and AKT inhibition) (details in supplementary Data and Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

Currently, there are eight ongoing phase I studies of MEK and AKT inhibitors in combination or which have recently completed recruitment (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=mek+akt). There is an urgent and unmet need to understand the relative contributions of inhibition of both these targets on cell growth in order to optimize these combinations because overlapping toxicities make them difficult to deliver [16, 19].

The cell lines with different mutations have been selected from various tumour types. It is now emerging that context specificity is important to feedback loops in signalling pathways [21], and future work will be better done in specific disease contexts. We considered a variety of methods that could potentially be used to understand individual contributions of MEK and AKT signalling. We chose to study p-ERK as a downstream readout of MEK inhibition as it downstream of MEK. We did not choose p-AKT Ser473 to study AKT inhibition as allosteric and ATP competitive drugs used to inhibit AKT caused diametrically opposite effects on phosphorylation at this site [4, 22]. We were not able to get consistent results showing reduction of p-m-TOR following AKT inhibition thus chose p-S6. This study could be potentially strengthened by in vivo experiments but would require an extremely large cohort of animals so was deemed as not justified. Our study did not to study feedback loops activating receptor tyrosine that can be caused by MEK or AKT inhibition as this has been done before [23].

When MEK and AKT inhibitors were used as single agents, the findings that BRAFM and PIK3CAM cell lines in the panel were significantly more sensitive to MEK and AKT inhibitors, respectively. However, KRASM cell lines in the panel were either significantly more sensitive to AKT (H23, H441) or MEK (SW620) inhibition in some instances or equally sensitive to MEK and AKT inhibition (A549, H1734), suggesting that it is likely that cells with KRAS mutations are not predominantly dependant on MEK or AKT signalling alone for cell growth. Our findings that KRASM cancers could respond to combinations of MEK + AKT inhibitors is interesting and other groups have shown MEK + AKT inhibitors could be effective in cells with mutations both in KRAS and PIK3CA [24].

All five BRAFM cell lines that were significantly more sensitive to MEK inhibition and only 1/5 BRAFM cell lines showed incremental growth inhibition by addition of maximal AKT inhibition to maximal MEK inhibition. The cell line SKMEL-5 was shown to be sensitive to MEK inhibition but additive growth inhibition was observed upon AKT inhibition. SKMEL-5 cells are known to have a BRAF mutation but no PTEN loss [25] and previous studies have suggested signalling through IGFR-1 is a potential mechanism of resistance to MEK inhibitors in this cell line [9]. Our findings are interesting and show that, for the first time, combinations of MEK + AKT inhibitors are unlikely to be of added benefit to MEK inhibitors alone in cell line models studied which have only BRAF mutations. It is possible that cell lines with BRAF and PIK3CA mutations may benefit from the combination. The findings contradict pre-clinical studies that suggest melanomas with BRAF mutation may benefit from inhibition of dual MEK and PI3K pathway inhibition [13, 26]. All the PIK3CAM cell lines studied were more sensitive to AKT inhibition and PIK3CAM sensitizing cells to AKT mutation has been shown before [27]. However, 3/5 PIK3CAM cell lines in our study showed significantly more growth inhibition with the combination of maximal AKT + MEK inhibition suggesting that the combination of MEK + AKT inhibition may be of benefit to PIK3CAM cancers.

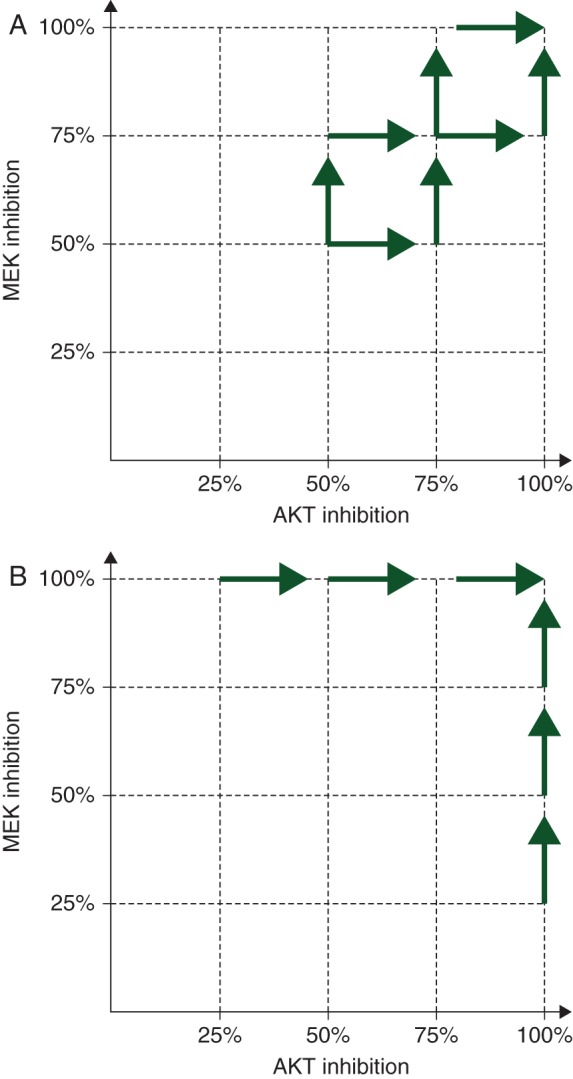

Crucially, our studies show for the first time that in only 1/20 cell lines did a combination of sub-maximal inhibition of MEK + AKT cause a significantly greater growth inhibition compared with growth inhibition caused by maximal MEK or AKT inhibition alone (whichever the cell line was sensitive to, or both, if the cell line was equally sensitive to MEK and AKT inhibition). This is particularly relevant as it is often difficult to deliver full does of combinations of MEK and PI3K pathway inhibitors in the clinic [16]. However, the effect of sub-optimal inhibition of signal transduction on evolution of resistant clones has not been explored in the present study and such experiments may provide further insights into the use of combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors. The dependence on the degree of inhibition of p-ERK to clinical response in BRAFM cancers has been previously described and supports our findings [28]. Currently, clinical trials exploring these combinations often started with sub-optimal inhibitory doses of both MEK and AKT inhibitors. The present pre-clinical data suggest that it is preferable to start with the dose of the MEK or AKT inhibitor which causes maximal pharmaco-dynamic inhibition and then add progressively higher doses of the second drug, with the aim of reaching the maximal doses of both drugs (Figure 4). If it is not possible to clinically achieve maximal inhibition of one or both pathways as continuous dosing schedules, intermittent schedules could be considered [19].

Figure 4.

Dose escalation paradigms in phase I studies of combinations of MEK and AKT inhibitors. (A) Current dose escalation strategies of MEK and AKT inhibitors start at doses of MEK and AKT inhibitors lower than the doses that cause maximal pharmaco-dynamic effects for both drugs defined in phase I studies. (B) The proposed dose escalation schedule at two different cohorts, the first starts with the dose of the MEK inhibitor that causes maximal pharmaco-dynamic effects and additional cohorts of increasing doses of AKT inhibitor are added. The second starting cohort will start with a dose of AKT inhibitor that causes maximal pharmaco-dynamic effects and additional cohorts of patients with increasing does of MEK inhibitor will be added. This model always has a dose of MEK or AKT inhibitor that maximally inhibits its intended target.

Experiments in this manuscript also attempted to answer the effects of inhibition of MEK and AKT on normal tissue and thus potential toxicity experienced by patients. Importantly, sub-optimal MEK or AKT inhibition in combination when compared with maximal MEK and AKT alone did not cause more growth inhibition in both HUVEC and Ker-CT cell lines, suggesting no additional toxicity once MEK or AKT is completely inhibited if a second inhibitor is added. In clinical practice that is not true as we struggle to deliver full doses of combinations of both drugs. It is possible that this is due to the selective susceptibility of different cell types that make up normal tissue such as skin and the gut.

This study provides insights into ways of clinically combining MEK and AKT inhibitors.

funding

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (grant number C309/A11566). Support was also provided by a joint initiative of Cancer Research UK and the Department of Health of an Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre award (programme grant) to the Institute of Cancer Research (grant number C12540/A15573), and by a National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre award (jointly to The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research).

disclosure

AS, PT, JSB and UB are employees of The Institute of Cancer Research, which has commercial interests in the discovery and development of AKT and AGC kinase inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

references

- 1.Banerji U, Camidge DR, Verheul HM et al. The first-in-human study of the hydrogen sulfate (Hyd-sulfate) capsule of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886): a phase I open-label multicenter trial in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 1613–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 782–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendell JC, Papadopoulous K, Jones S et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of MEK inhibitor MEK162 (ARRY-438162) in patients with advanced solid tumors. In Proceedings of the AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference: Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2011; 10(11 Suppl): abstr B243. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yap TA, Yan L, Patnaik A et al. First-in-man clinical trial of the oral pan-AKT inhibitor MK-2206 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4688–4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan Y, Serra V, Prudkin L et al. Evaluation and clinical analyses of downstream targets of the Akt inhibitor GDC-0068. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19: 6976–6986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerji U, Ranson M, Schellens J et al. Results of two phase I multicenter trials of AZD5363, an inhibitor of AKT1, 2 and 3: Biomarker and early clinical evaluation in Western and Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. In Proceedings of the 104th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cancer Res 2013; 73(8 Suppl): abstr LB66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Lazikani B, Banerji U, Workman P. Combinatorial drug therapy for cancer in the post-genomic era. Nat Biotechnol 2012; 30: 679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turke AB, Song Y, Costa C et al. MEK inhibition leads to PI3K/AKT activation by relieving a negative feedback on ERBB receptors. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 3228–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopal YN, Deng W, Woodman SE et al. Basal and treatment-induced activation of AKT mediates resistance to cell death by AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in Braf-mutant human cutaneous melanoma cells. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 8736–8747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity: evolution through space and time. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 4875–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng J, Dai B, Fang B et al. Combination treatment with MEK and AKT inhibitors is more effective than each drug alone in human non-small cell lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2010; 5: e14124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoeflich KP, O'Brien C, Boyd Z et al. In vivo antitumor activity of MEK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors in basal-like breast cancer models. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 4649–4664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lasithiotakis KG, Sinnberg TW, Schittek B et al. Combined inhibition of MAPK and mTOR signaling inhibits growth, induces cell death, and abrogates invasive growth of melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128: 2013–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renshaw J, Taylor KR, Bishop R et al. Dual blockade of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR (AZD8055) and RAS/MEK/ERK (AZD6244) pathways synergistically inhibits rhabdomyosarcoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19: 5940–5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolcher AW, Khan K, Ong M et al. Antitumor activity in RAS-driven tumors by blocking AKT and MEK. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 739–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu T, Tolcher AW, Papadopoulos KP et al. The clinical effect of the dual-targeting strategy involving PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MEK/ERK pathways in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 2316–2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampath D, Malik A, Plunkett W et al. Phase I clinical, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of the Akt-inhibitor triciribine phosphate monohydrate in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Leuk Res 2013; 37: 1461–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan Y, Wagle M, Punnoose E et al. A first-in-human trial of GDC-0068: A novel ATP-competitive AKT inhibitor, demonstrates robust suppression of the AKT pathway in surrogate tumour tissues. In Proceedings of the AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference: Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2011; 10(11 Suppl): abstr B154. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yap TA, Omlin A, de Bono JS. Development of therapeutic combinations targeting major cancer signaling pathways. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 1592–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerji U, Walton M, Raynaud F et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitor 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in human ovarian cancer xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 7023–7032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 2012; 483: 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies BR, Greenwood H, Dudley P et al. Preclinical pharmacology of AZD5363, an inhibitor of AKT: pharmacodynamics, antitumor activity, and correlation of monotherapy activity with genetic background. Mol Cancer Ther 2012; 11: 873–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Scaltriti M et al. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell 2011; 19: 58–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med 2008; 14: 1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies MA, Stemke-Hale K, Lin E et al. Integrated molecular and clinical analysis of AKT activation in metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 7538–7546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atefi M, von Euw E, Attar N et al. Reversing melanoma cross-resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors by co-targeting the AKT/mTOR pathway. PLoS One 2011; 6: e28973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.She QB, Chandarlapaty S, Ye Q et al. Breast tumor cells with PI3K mutation or HER2 amplification are selectively addicted to Akt signaling. PLoS One 2008; 3: e3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature 2010; 467: 596–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.