Oral S-1 plus cisplatin is noninferior to docetaxel plus cisplatin in terms of overall survival with favorable QoL data. S-1 plus cisplatin is an option for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC.

Keywords: advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer, S-1, cisplatin, docetaxel, randomized trial

Abstract

Background

Platinum-based two-drug combination chemotherapy has been standard of care for patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The primary aim was to compare overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced NSCLC between the two chemotherapy regimens. Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), response, safety, and quality of life (QoL).

Patients and methods

Patients with previously untreated stage IIIB or IV NSCLC, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1 and adequate organ function were randomized to receive either oral S-1 80 mg/m2/day on days 1–21 plus cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 8 every 4–5 weeks, or docetaxel 60 mg/m2 on day 1 plus cisplatin 80 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3–4 weeks, both up to six cycles.

Results

A total of 608 patients from 66 sites in Japan were randomized to S-1 plus cisplatin (n = 303) or docetaxel plus cisplatin (n = 305). OS for oral S-1 plus cisplatin was noninferior to docetaxel plus cisplatin [median survival, 16.1 versus 17.1 months, respectively; hazard ratio = 1.013; 96.4% confidence interval (CI) 0.837–1.227]. Significantly higher febrile neutropenia (7.4% versus 1.0%), grade 3/4 neutropenia (73.4% versus 22.9%), grade 3/4 infection (14.5% versus 5.3%), and grade 1/2 alopecia (59.3% versus 12.3%) were observed in the docetaxel plus cisplatin than in the S-1 plus cisplatin. There were no differences found in PFS or response between the two arms. QoL data investigated by EORTC QLQ-C30 and LC-13 favored the S-1 plus cisplatin.

Conclusion

Oral S-1 plus cisplatin is not inferior to docetaxel plus cisplatin and is better tolerated in Japanese patients with advanced NSCLC.

Clinical trial number

UMIN000000608.

introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Although age-adjusted lung cancer mortality has been declining due to decreased tobacco consumption in industrialized countries, the disease is a growing problem in developing countries [1, 2]. Nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% of lung cancer, and most symptomatic patients have advanced disease at presentation. Platinum-based combination chemotherapy has been the mainstay of care for patients with stage III and IV NSCLC [3]. Molecularly targeted therapy, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), significantly improves QoL and prognosis of patients who harbor driver mutations; however, most patients who had response to TKIs had disease progression 9–10 months after start of the treatment and became candidates for cytotoxic chemotherapy [4–7]. Thus, improvement of combination chemotherapy is still a clinically meaningful strategy.

Docetaxel plus cisplatin (DP) is the only third-generation chemotherapy regimen that has demonstrated significant improvement in overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL) compared with vindesine plus cisplatin, a second-generation chemotherapy regimen, in patients with stage IV NSCLC in Japan [8]. A larger randomized trial comparing DP with vinorelbine plus cisplatin also demonstrated improved QoL and OS, favoring DP [9]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of docetaxel- and vinca alkaloid-based chemotherapy, mainly vinorelbine, revealed superior OS of docetaxel [10].

S-1 (TS-1®; Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) is an oral fluoropyrimidine anticancer agent combining tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil potassium in a molar ratio of 1.0:0.4:1.0 [11]. Single-agent S-1 is active in NSCLC [12]. In a phase II trial of S-1 plus cisplatin (SP), in which cisplatin (60 mg/m2) was given on day 8 and S-1 (80 mg/m2) was given on days 1–21 every 4–5 weeks, a response of 47% and a median survival of 11 months were attained in 55 patients with advanced NSCLC [13]. A phase I/II trial of a triweekly regimen with S-1 for 14 days plus cisplatin on day 1 revealed that the recommended dose of cisplatin was 60 mg/m2. Among 55 eligible patients treated at the recommended dose, a response was observed in 33% of patients, and the median survival time was 18.1 months [14]. This promising activity was demonstrated together with a more favorable toxicity profile than that of commonly used platinum two-drug combination regimens.

We conducted a randomized, open-label, phase III, noninferiority trial that compared SP with DP. The primary aim of this study was to compare OS of patients with advanced NSCLC between the two regimens. QoL was also evaluated as a secondary end point.

methods

patients

All patients enrolled in this study had cytologically or histologically confirmed NSCLC, with stage IIIB or IV (tumour–node–metastasis classification, 5th edition) or postoperative recurrence. Previous chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy of the primary lesion were not allowed. Other eligibility requirements included: age of 20–74 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 or 1, and adequate organ function, measurable or evaluable lesion, and an expected survival of at least 12 weeks. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment in this study. The protocol was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical guidelines for clinical research and was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

randomization

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either SP or DP at the Tokyo Cooperative Oncology Group registration center. Randomization was conducted by fax and carried out with a dynamic randomization schema after stratifying patients according to disease stage (stage IIIB, stage IV, or postoperative recurrence), sex (male or female), and histologic type (adenocarcinoma or nonadenocarcinoma).

treatment

Patients assigned to the SP group received oral S-1 (80 mg/m2) in two divided doses daily after meals on days 1–21 and cisplatin (60 mg/m2) as an i.v. infusion on day 8, repeated every 4–5 weeks. The dose of S-1 was assigned according to body surface area (BSA) as follows: BSA <1.25 m2, 80 mg/day; BSA 1.25 m2 to <1.50 m2, 100 mg/day; and BSA 1.5 m2 or higher, 120 mg/day. Patients assigned to the DP group received an i.v. infusion of docetaxel (60 mg/m2) and cisplatin (80 mg/m2) on day 1, repeated every 3–4 weeks. In both treatment groups, patients received a minimum of three cycles until the onset of progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity. The maximal number of chemotherapy cycles was 6.

baseline and treatment assessments

Pretreatment assessments included physical examination, complete blood count and serum chemistry; brain, chest, and abdominal computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, bone scintigraphy, or positron emission tomography. Physical examination, complete blood, and serum chemistry were carried out weekly during the first cycle of chemotherapy and at least once before the start of the second and each subsequent cycle of chemotherapy. Scans or radiographs used to assess response were obtained every 4–6 weeks. Responses were evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.0. Adverse events were evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 3.0.

OS was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from randomization to either progressive disease or death, whichever came first. Time-to-treatment failure (TTF) was defined as the time from randomization to death, progressive disease, or cessation of treatment before completion, whichever came first. QoL was evaluated with the use of the European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [15] and a 13-item lung cancer-specific questionnaire module (EORTC QLQ-LC13). Patients responded to this questionnaire before starting the first cycle of treatment, 1 week after cisplatin administration during the first cycle of treatment, and on completion of two cycles of treatment.

statistical analysis

The full analysis set (FAS) included all patients who received the study treatment at least once, were observed for survival, and did not violate the eligibility criteria. The safety analysis set was defined as all patients who received the study treatment at least once. The primary end point was OS. For the FAS, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Secondary end points were PFS, TTF, overall response, adverse events, and QoL. It was assumed that the 1-year survival in the DP group would be 60%, and the noninferiority margin was set at ∼10%, which corresponds to a HR of 1.322. We decided this setting was justified considering the favorable toxicity profile of SP. Given a one-sided significance level of 0.025, a statistical power of 0.85, an enrollment period of 2.5 years, and a follow-up period of 2 years, 290 patients per treatment group would be required. The total target number of patients was therefore set at 600. Two prespecified interim analyses were carried out, one 2.5 years after the start of the study and the other 1 year after the completion of enrollment. For OS, adjustment for multiplicity was carried out with a Lan–DeMets boundary and an O′Brien–Fleming–type alpha spending function. A one-sided significance level was set at 0.018 for the final analysis. All reported P values are two-sided. The analysis results are reported as HRs with a 96.4% CI for OS or a 95% CI for PFS and TTF. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data analyses were conducted by coauthors (MT and HM) at the Department of Clinical Medicine (Biostatistics and Pharmaceutical Medicine), Kitasato University School of Pharmacy.

results

patient characteristics

A total of 608 patients were enrolled in the trial between April 2007 and December 2008 from 66 institutions in Japan, 303 patients in the SP group and 305 patients in the DP group. Two patients in the SP group and eight in the DP group did not receive their assigned treatments. Safety was therefore assessed in 301 patients in the SP group and 297 in the DP group. Two patients in the DP group were subsequently found to be ineligible. The final number of subjects was therefore 301 in the SP group and 295 in the DP group (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The demographic characteristics of the patients did not differ between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| n (%) | S-1 plus cisplatin (N = 301) | Docetaxel plus cisplatin (N = 295) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Average (SD) | 61.4 (8.7) | 62.8 (7.8) |

| Median (range) | 62 (25–74) | 64 (35–74) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 211 (70.1%) | 208 (70.5%) |

| Female | 90 (29.9%) | 87 (29.5%) |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 228 (75.8%) | 222 (75.3%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 50 (16.6%) | 48 (16.3%) |

| Large-cell carcinoma | 5 (1.7%) | 5 (1.7%) |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 7 (2.3%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Other | 11 (3.7%) | 19 (6.4%) |

| Clinical stage | ||

| Stage IIIB | 79 (26.3%) | 78 (26.4%) |

| Stage IV | 201 (66.8%) | 192 (65.1%) |

| Postoperative recurrence | 21 (7.0%) | 25 (8.5%) |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 151 (50.2%) | 152 (51.5%) |

| 1 | 150 (49.8%) | 143 (48.5%) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Previous/current smoker | 223 (74.1%) | 222 (75.3%) |

| Never smoker | 78 (25.9%) | 73 (24.8%) |

| EGFR status | ||

| Wild type | 113 (37.5%) | 115 (39.0%) |

| Mutant | 43 (14.3%) | 46 (15.6%) |

| Unknown or missing | 145 (48.2%) | 134 (45.4%) |

efficacy

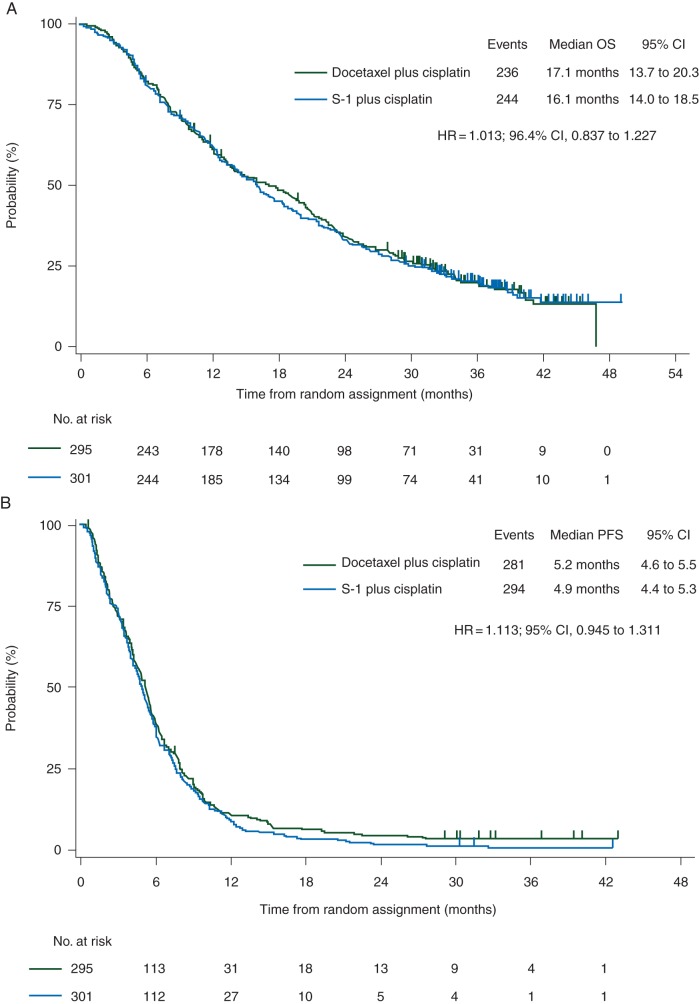

The median survival time was 16.1 months in the SP group and 17.1 months in the DP group (HR, 1.013; 96.4% CI 0.837–1.227) (Figure 1A). The upper limit of HR was lower than 1.322, the prespecified upper limit of the noninferiority margin, demonstrating that SP was noninferior to DP with regard to the primary end point of OS. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year survivals were 62% (95% CI 0.56–0.67), 33% and 20%, respectively, in the SP group, and 61% (95% CI 0.55–0.66), 34% and 20%, respectively, in the DP group. The results of subgroup analyses of OS were similar to those of the primary analysis, and there were no significant differences between the groups (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) for the FAS population.

The median PFS was 4.9 months in the SP group and 5.2 months in the DP group (HR, 1.113; 95% CI 0.945–1.311) (Figure 1B). The median TTF was 4.2 months in the SP group and 4.4 months in the DP group (HR, 1.088; 95% CI 0.925–1.280). The overall response was 26.9% in the SP group [complete response (CR), 1 patient; partial response (PR), 77] and 31.3% in the DP group (CR, 2; PR, 87). The proportion of disease control was similar in the SP group (74.1%) and the DP group (76.4%). The mean of dose intensity of cisplatin was 11.47 and 15.13 mg/m2/week in the SP and DP group, respectively.

Poststudy treatment and treatment compliance are shown in supplementary Appendix A1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

safety

Grade 3 or 4 febrile neutropenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia were significantly less frequent in the SP group than in the DP group (Table 2). Grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia was significantly more frequent in the SP group. More grade 3 or 4 infection was observed in the DP group (14.5%) than in the SP group (5.3%). All grades of anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and hair loss were significantly less frequent in the SP group (Table 2). There was one treatment-related death in the SP group (suffocation due to vomiting).

Table 2.

Common adverse events

| CTCAE grade (n, %) | S-1 plus cisplatin (N = 301) |

Docetaxel plus cisplatin (N = 297) |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | ≥Grade3 | All grades | ≥Grade3 | ||

| Hematologic | (≥Grade 3) | ||||

| Leukocytes | 147 (48.8) | 24 (8.0) | 259 (87.2) | 164 (55.2) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils | 152 (50.5) | 69 (22.9) | 252 (84.8) | 218 (73.4) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 203 (67.4) | 41 (13.6) | 249 (83.8) | 53 (17.8) | 0.178 |

| Platelets | 144 (47.8) | 17 (5.6) | 83 (27.9) | 4 (1.3) | 0.006 |

| Nonhematologic | (All grades) | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) | 22 (7.4) | 22 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Mucositis/stomatitis (clinical exam) | 42 (14.0) | 6 (2.0) | 23 (7.7) | 0 | 0.018 |

| Mucositis/stomatitis (functional/symptomatic) | 58 (19.3) | 6 (2.0) | 33 (11.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0.006 |

| Anorexia | 229 (76.1) | 53 (17.6) | 257 (86.5) | 81 (27.3) | 0.001 |

| Nausea | 201 (66.8) | 29 (9.6) | 232 (78.1) | 59 (19.9) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting | 84 (27.9) | 12 (4.0) | 155 (52.2) | 24 (8.1) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 95 (31.6) | 18 (6.0) | 95 (32.0) | 11 (3.7) | 0.930 |

| Hair loss/alopecia | 37 (12.3) | 0 | 176 (59.3) | 0 | <0.001 |

QoL

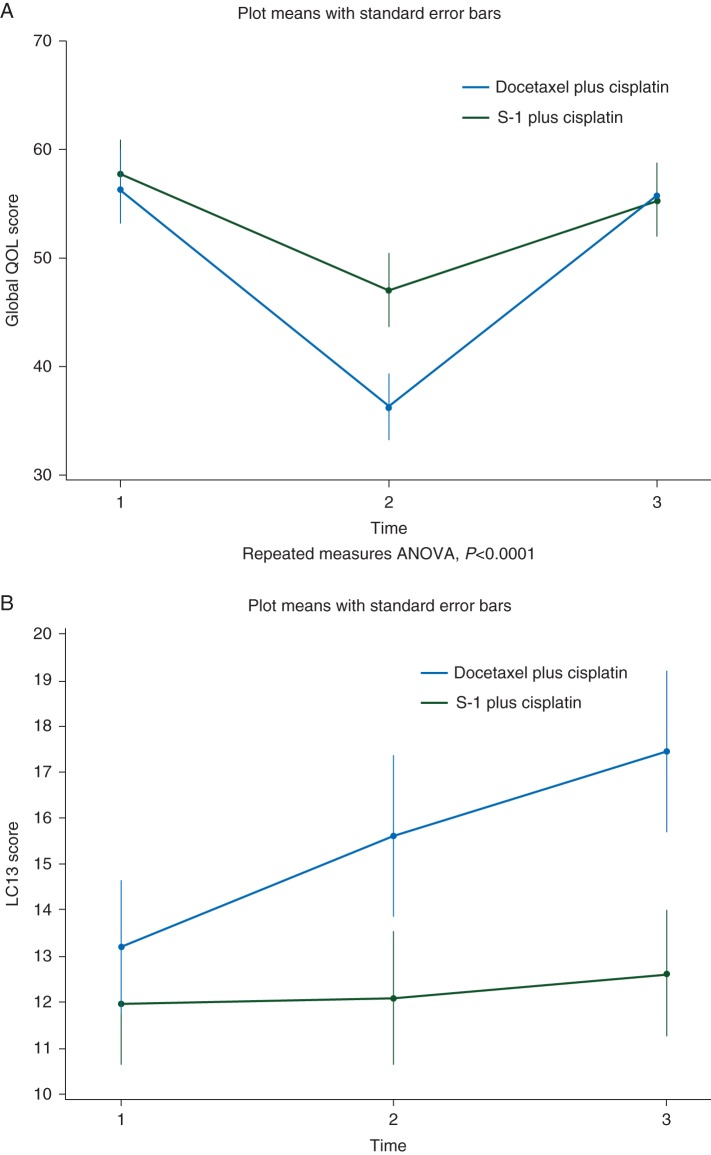

Of 301 patients in the SP group and 295 patients in the DP group, 229 (76%) and 235 patients (80%), respectively, answered the questionnaires all three times. It was found as a primary measure of QoL that Global Health Status/QoL functioning was better in patients treated by SP than in those treated by cisplatin plus docetaxel. (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A) Physical functioning was also better in SP. (P = 0.0058) Furthermore, good results for scale sores of fatigue, nausea, and vomiting, pain, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, and diarrhea were obtained in the SP, and the difference in QoL during treatment (1 week after the first dose of cisplatin) was particularly remarkable (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Interesting, QoL measured by the QLQ-LC13 was better in the SP group not only at the second measurement but also at the third measurement (P < 0.01) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Quality-of-life assessments with EORTC QLQ-C30 (A) Score changes of Global Health Status/QoL (items 29 and 30) in the EORTC QLQ-C30. Patients responded to EORTC QLQ-C30 three times: (1) before each treatment, (2) 1 week after the first dose of cisplatin, and (3) at the end of the second course. A high score for the Global Health Status/QoL represents a high QoL. Quality-of-life assessments with EORTC QLQ-LC13 (B) Score changes in the EORTC QLQ-LC13. Patients responded to EORTC QLQ-LC13 three times: (1) before each treatment; (2) 1 week after the first dose of cisplatin; and (3) at the end of the second cycle. A low score for the Global Health Status/QoL represents a high QoL.

discussion

The present study showed that compared with DP, SP is noninferior in terms of OS in patients with advanced NSCLC. As a result, 1-, 2-, and 3-year survivals were similar between the two groups. Notably, QoL during chemotherapy favored SP. Response and PFS also did not differ between the two groups. Although interaction P value by PS was 0.0494, subgroup analysis by PS was not significant between the two groups.

Before starting the study, we defined clinically meaningful adverse events such as neutropenic fever, neutropenia, infection, gastrointestinal toxicity, and alopecia. Grade 3 or 4 of these toxicities was less frequent in the SP arm. Although there was no difference in the frequencies of grades 3 or 4 diarrhea between the two arms, it would be important to instruct patients to stop S-1 when they have grade 2 or higher diarrhea.

Although the dose intensity of cisplatin (11.47 mg/m2/week) in SP group was 24.19% lower than that (15.13 mg/m2/week) in DP group, SP regimen showed similar efficacy to DP regimen in terms of PFS (HR, 1.113; 95% CI 0.945–1.311), OS (HR, 1.013; 96.4% CI 0.837–1.227). Because optimum dose intensity of cisplatin for patients with NSCLC has not been determined, the present data might be valuable for optimum dose and schedule of cisplatin in the future trial.

Based on the landmark, randomized trial conducted by Temel et al. [16], QoL should be an explicit priority for health care professionals throughout the course of advanced cancer care. A randomized trial of DP compared with vinorelbine plus cisplatin showed global QoL and the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale in favor of DP [9]. The favorable QoL data shown in the present trial of SP during chemotherapy were consistent with the less toxicity profile.

The present study contains some limitations: first, the noninferiority margin of 1.322 in the study might be large. Actual 1-year survival was 61% in the DP and 62% in the SP, and upper limit of HR was 1.227. The OS curves of both groups were almost identical. Second, EGFR mutation status or ALK rearrangement were not all evaluated. When the study started in 2007, EGFR TKIs were used only in patients with NSCLC previously treated with chemotherapy, and the EGFR testing was not common in this setting. The proportion of patients with EGFR mutation who received EGFR TKIs was 14% in the SP and 15.5% in the DP group. The data suggest that the conclusion of the study would not be biased by EGFR mutation status and TKIs treatment. Third, because of possible pharmacogenomic differences between Asian and Caucasian patients regarding chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity [17, 18], the results of the present study may not be applicable to Caucasian patients. The recommended dose of S-1 is lower in Caucasian patients than in Asian patients [19].

S-1 was compared with paclitaxel when these agents were combined with carboplatin in patients with advanced NSCLC. That trial also showed noninferiority of S-1 plus carboplatin compared with paclitaxel plus carboplatin [20]. The introduction of newer generation antiemetics such as aprepitant and palonosetron, and short hydration in chemotherapy containing cisplatin reduced chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting and renal toxicity [21]. Thus, it would be reasonable to use SP as a first-line chemotherapy based on the OS and favorable toxicity profile confirmed by the QoL data. Another large-scale trial comparing pemetrexed plus cisplatin to gemcitabine plus cisplatin also confirmed noninferiority of pemetrexed plus cisplatin in patients with advanced NSCLC [22]. A subgroup analysis showed that pemetrexed plus cisplatin was more efficacious in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. After approval of pemetrexed for NSCLC in 2009, pemetrexed has been widely used as a first-line chemotherapy for advanced nonsquamous NSCLC in Japan. Such new data obtained after the start of the present trial could be potential obstacles to the acceptance of S-1 plus cisplatin as a standard first-line chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC.

In conclusion, SP is noninferior to DP in terms of OS with favorable QoL data. SP is an option for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC.

funding

This work was supported by TCOG. The Research fund was provided to TCOG by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd under the research contract. The funders did not have any involvement in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the article; or the decision to submit the article for publication. No grant numbers applicable.

disclosure

KK (Taiho, Sanofi), HS (Taiho, Chugai, Eli Lilly Japan), NK (Dainippon Sumitomo, Shionogi, Chugai Pharma, Boeringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Taiho, Sanofi), MN and AI (Taiho), HK, YT and AG (Taiho, Sanofi), KK (Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca), MT (Taiho), SK (Taiho, Sanofi) received honoraria. HK (Taiho) received travel grant. MT (Taiho) received consulting fee. KK and MN (Taiho), NK (Eisai, Ono, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Shionogi, Daiichi Sankyo, Chugai, Merck Serono, Astra Zeneca), HS (Chugai, Eli Lilly Japan), HO (Chugai, Dainippon Sumitomo, Takeda, Kyowa Hakko Kirin), and AG (Taiho, Sanofi) received research fundings. MF is shareholders of Chugai.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in this trial and Hiromi Odagiri for administrative support. A list of participating institutions is given in the supplementary Appendix A2, available at Annals of Oncology online.

references

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM et al. . Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin HR, Carlos MC, Varghese C. Cancer control in the Asia Pacific region: current status and concerns. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012; 42: 867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azzoli CG, Baker S Jr, Temin S et al. . American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6251–6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K et al. . Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 2380–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y et al. . Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S et al. . Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thongprasert S, Duffield E, Saijo N et al. . Health-related quality-of-life in a randomized phase III first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients from Asia with advanced NSCLC (IPASS). J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 1872–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubota K, Watanabe K, Kunitoh H et al. . Phase III randomized trial of docetaxel plus cisplatin versus vindesine plus cisplatin in patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer: the Japanese Taxotere Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fossella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J et al. . Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3016–3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douillard JY, Laporte S, Fossella F et al. . Comparison of docetaxel- and vinca alkaloid-based chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol 2007; 2: 939–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirasaka T, Nakano K, Takechi T et al. . Antitumor activity of 1 M tegafur-0.4 M 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine-1 M potassium oxonate (S-1) against human colon carcinoma orthotopically implanted into nude rats. Cancer Res 1996; 56: 2602–2606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawahara M, Furuse K, Segawa Y et al. . Phase II study of S-1, a novel oral fluorouracil, in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2001; 85: 939–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichinose Y, Yoshimori K, Sakai H et al. . S-1 plus cisplatin combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a multi-institutional phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 7860–7864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubota K, Sakai H, Yamamoto N et al. . A multi-institution phase I/II trial of triweekly regimen with S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010; 5: 702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi K, Takeda F, Teramukai S et al. . A cross-validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) for Japanese with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. . Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandara DR, Kawaguchi T, Crowley J et al. . Japanese-US common-arm analysis of paclitaxel plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a model for assessing population-related pharmacogenomics. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3540–3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubota K, Kawahara M, Ogawara M et al. . Vinorelbine plus gemcitabine followed by docetaxel versus carboplatin plus paclitaxel in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9: 1135–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajani JA, Faust J, Ikeda K et al. . Phase I pharmacokinetic study of S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 6957–6965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto I, Yoshioka H, Morita S et al. . Phase III trial comparing oral S-1 plus carboplatin with paclitaxel plus carboplatin in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a west Japan oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 5240–5246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horinouchi H, Kubota K, Itani H et al. . Short hydration in chemotherapy containing cisplatin (>/=75 mg/m2) for patients with lung cancer: a prospective study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013; 43: 1105–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J et al. . Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 3543–3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.