Abstract

The H1N1 influenza virus is a serious threat to human population. Oseltamivir and Zanamivir are known antiviral drugs for swine flu with observed side effects. These drugs are viral neuraminidase and hemagglutinin inhibitor prevents early virus multiplication by blocking sialic acid cleavage on host cells. Therefore, it is of interest to identify naturally occurring novel compounds to control viral growth. Thus, H1N1 proteins (neuraminidase and hemagglutinin) were screened with phytocompounds isolated from Tulsi plant (Ocimum sanctum L.) using molecular docking tools. This identified Apigenin as an alternative to Oseltamivir and Zanamivir with improved predicted binding properties. Hence, it is of interest to consider this compound for further in vitro and in vivo evaluation.

Keywords: Swine Flu, H1N1, Docking, ADMET

Background

Influenza virus is continually changing every decade or so, a dangerous new strain appears and poses a threat to public health. The subtypes of influenza virus are H1N1, H1N2, H3N1, H3N2, H2N3 and H5N1 [1]. The current H1N1 virus strain is a mixture of human, pig and bird genes and has proved to be very contagious, but no more deadly than common seasonal flu viruses. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported about 15,174 deaths due to the pandemic influenza virus H1N1. According to the Hindu news paper, the current cases of swine flu H1NI version have been reported in India with over 31,156 positive test cases and 1,841 deaths till March 2015. Influenza A virus mutates frequently because of their segmented RNA genome, making it almost impossible to produce a timely and sufficiently effective [2]. The H1N1 designation refers to the two molecules that cover the surface of the virus are hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. These are the two important glycoproteins responsible for viral influenza infection [3]. Hemagglutinin is present on the surface of the virion and is needed for infection, while neuraminidase is responsible for cleavage of sialic acid (neuraminic acid) from glycans of the infected cell [4]. These two proteins are drug targets for viral infections, and the neuraminidase inhibitors, Oseltamivir and Zanamivir, are broad spectrum antiviral drugs, useful for the treatment of a variety of forms of influenza [5].

Medicinal plants are termed to be one of the easiest sources to get antiviral drugs since they have a proven record for antiviral activity. Tribes living worldwide, traditionally, have been using most of the medicinal plants successfully for many decades [6]. Ocimum sanctum L. (Tulsi) is a plant which is grown in different parts of the world and are known to have medicinal properties. Tulsi plant has been known to possess antibacterial, antifungal, antianaphylactic activity, antihistamine and mast cell stabilizing activity, radio-protective effect, wound healing effect, antidiabetic effect, antioxidant activity, immunologic effects, anticancer properties, contraceptive effects, larvicidal property, Neuro-protective effects, antigenotoxic effect, cardioprotective effect and other miscellaneous activities [7]. A wide range of phytocompounds including euginal, eugenol, carvacrol, urosolic acid, linalool, limatrol, methyl carvicol, caryophyllene, antocyans, sistosterol, apigenin has been reported in this plant [8]. Tulsi has also reported for its antiviral effect, based on this background a screening of its phytocompounds will be helpful for new therapeutic agent preparation of the medicinal plant which can be helpful for the humans to overcome influenza since the virus was reported for its high mutation ability against drugs.

Investigation on prevention and cure of H1N1 still remains as an unresolved challenge in the area of Bioinformatics and Pharmacogenomics. This required a serious hunt for better antiviral drugs. A proportional study on the effectiveness of the known drugs can identify the drug with maximum interaction with the receptor protein among the available drugs. Such knowledge is essential for the researchers to discover a potential new drug for H1N1. In our study, we compare the effectiveness of the available 38 phytocompounds of Tulsi plant as a drug and a positive control drug (Oseltamivir, Zanamivir) in terms of binding energy between the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase viral proteins in silico techniques. We adopted the in silico techniques such as docking, drug screening to find the most potent drug among the available drugs. If these compounds selectively bind to specific targets than the control drug then they could potentially be used more broadly in H1N1 influenza prevention or treatment.

Methodology

Preparation of ligand structure:

The ligands used in this study were downloaded from PubChem Database. A total of thirty eight test compound of Tulsi and two standard control compound structures (Oseltamivir, Zanamivir) was downloaded in the SDF format were first converted to the PDB format using Open Babel. The ligands and their SDF structures where give in Supplementary Figure 1 (see supplementary material). Then the Gasteiger charges and rotatable bonds were then assigned to the PDB ligands using Auto Dock Tool [9]. All rotatable bonds were allowed to move freely.

Preparation of protein structure:

Eight protein X-ray crystal structures from the Protein Data Bank were downloaded based on the literature survey. The proteins and their PDB structure identifiers and the active site are given in Table 1 (see supplementary material). All the proteins had co-crystallized ligands (X-ray ligand) in the binding site. The ligand enclosed in each protein structure was removed from the binding site and saved to a new file. In each protein structure the missing atoms were searched for and fixed using Swiss PDB [10]. The Gasteiger charges and the solvation term were then added to the protein structure using the AutoDockTool.

Protein-Ligand Docking:

Grid box generation:

The grid parameter file of each protein was generated using AutoDock Tool. A grid-box was created that was large enough to cover the entire protein binding site and accommodate all ligands to move freely in it. The number of grid points in x, y, and z-axes were set to 20×20×20. The distance between two connecting grid points was 0.375 Å. The center of the ligand in the X-ray crystal structure was used as the center of the gridbox. To the protein structures that do not have ligands in the binding site, the center of the active binding site was estimated from the structure and taken as the center of the grid-box.

Ligand docking:

The docking of ligands to the catalytic triad of protein was performed using AutoDock Vina software [11]. Docking was performed to obtain a population of possible conformations and orientations for the ligand at the binding site. Polar hydrogen atoms were added to all the proteins and its nonpolar hydrogen atoms were merged by using the software. All bonds of ligands were set to be rotatable. All calculations for ligandflexible protein-fixed docking were performed using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) method. The best conformation was chosen with the lowest docked energy, after the completion of docking search. Standard docking settings were used and the 10 energetically most favorable binding poses are outputted.

Drug scans:

This was performed in order to determine the inhibitor has fulfilled the conditions as the drug candidate based on Lipinski׳s Rule of Five [12]. It is done using Lipinski Filters, Molinspiration (http://www.molinspiration.com/cgi-bin/properties), admetSAR (http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn:8000/), and Toxtree v2.5.1, software platforms (http:// toxtree.sourceforge.net/). Molinspiration and Lipinski Filters were applied for studying the molecular attributes, such as the quantity of hydrogen bond acceptor, the amount of hydrogen bond donors, Log P, and the molecular mass of the drugs. In addition, the admetSAR and Toxtree v2.5.1, calculated various attributes of the drugs, BBB, Human Intestinal absorption, Caco-2 permeable, Aqueous solubility, P-gp substrate and inhibitor, CYP450 substrate and inhibitor, CYP IP, ROCT, HERG inhibition, and toxicity parameters. In order to use Lipinski Filters, the ligand in SMILE format was uploaded to the analysis software website. The same applies to Molinspiration, admetSAR and Toxtree v2.5.1, because the ligand in smiles format must be uploaded to their website.

Result & Discussion

Docking:

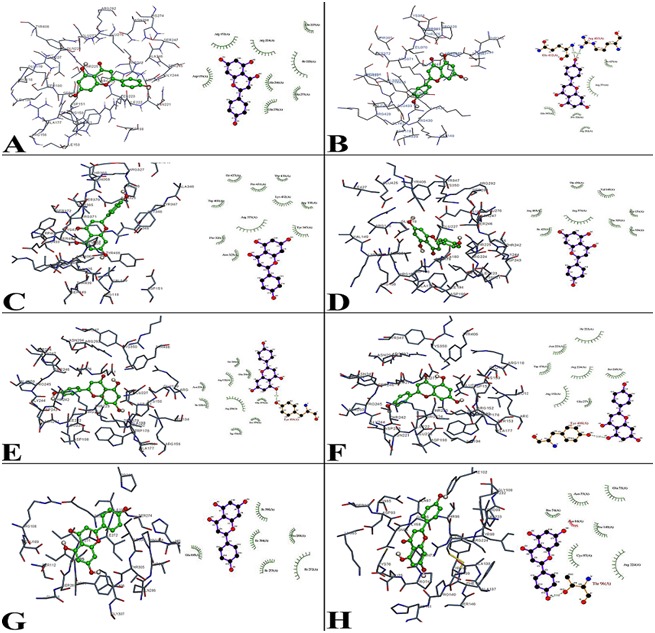

Molecular docking enables a scientist to virtual screen a number of candidate compounds based on their binding orientation and binding ability with a target particle. It also allows one to select compounds with strong affinity for the target site. In the current study, thirty eight phytocompounds of Tulsi were docked in silico with the eight H1N1 viral proteins and compared with the positive drugs Oseltamivir and Zanamivir. The docked ligand molecules were selected based on highest binding energy and good interaction with the active site residues and the results are shown in Table 1 (see supplementary material) and Figure 1. We selected top five ligands namely Oleanolic acid, Vicenin- 2, Apigenin, Stigmasterol, and Ursolic acid out of thirty eight ligands as compared to the positive ligands. These five molecules showed the highest binding energy of greater than standard drugs in the kcal/mol to all the H1N1 viral protein receptors.

Figure 1.

Molecular docking interaction between Apigenin molecule with Influenza viral proteins such as (PDB ID) A) 1NCA; B) 1NN2; C) 2HU4; D) 3CL2; E) 3B7E; F) 3CKZ, are Neuraminidase proteins, G) 3AL4 and H) 3LZG are Hemagglutinin proteins binding energy and their ligplot interaction energy were calculated based on hydrogen bonds, polar, cation-pi, hydrophobic and other energies. Apigenin showed the highest binding energy with all the viral protein as compared to the control ligands based on the molecular docking and ligplot interaction.

Drug Scan (ADMET Analysis):

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity (ADME/Tox) are main five parameters to test the drug likeness of a molecule. Based on the docking study, top five potential ligands molecular structure was submitted to Molinspiration, admetSAR and Toxtree servers to determine their different ADMET properties. Only Apigenin and Oseltamivir followed the Lipinski׳s rule of five without any violations with respect to an octanol-water partition coefficient (LogP ≤ 5), molecular weight (≤ 500 KDa), number of H-bond donors (≤ 5), number of H-bond acceptors (≤ 10), molecular refractivity (40–130) as tabulated in Table 3 (see supplementary material), whereas remaining ligands including Zanamivir didn׳t follow Lipinski׳s rule of five. Considering this only Apigenin was considered as drug candidate for further ADMET analysis including Oseltamivir and Zanamivir.

In ADME assessment, different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters were considered such as aqueous solubility, human intestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier penetration, Caco-2 permeability, cytochrome P450 inhibition, renal organic cation transportation, HERG inhibition. The results have been summarized in Table 4 (see supplementary material). Interestingly, the analysis performed on admetSAR revealed that only Apigenin had no substantial ADME properties that could cause adverse effects in humans. Whereas Oseltamivir and Zanamivir have potentially showed adverse effects with blood-brain barrier and Caco-2 penetration. Zanamivir has also showed negative responses for human intestinal absorption.

The BBB is a highly selective permeability barrier that separates the circulating blood from the brain extracellular fluid in the CNS. BBB is formed by the brain capillary endothelium and excludes from the brain ~100% of large-molecule neurotherapeutics and more than 98% of all small-molecule drugs [13]. Mechanisms for drug targeting in the brain involve going either “through” or “behind” the BBB. Modalities for drug delivery/dosage form through the BBB entail its disruption by osmotic means; biochemically by the use of vasoactive substances such as bradykinin; or even by localized exposure to high-intensity focused ultrasound. Dangerous leaks of BBB breaks down, leads to brain cancers, brain infections, neurodegenerative disorders and multiple sclerosis [14]. Predicting human intestinal absorption (HIA%) of drugs is very important for identifying potential drug candidate. HIA% data are the sum of bioavailability and absorption evaluated from the ratio of excretion or cumulative excretion in urine, bile and feces [15]. For the development of bioactive molecules as therapeutic agents, oral bioavailability is often an important consideration. The prediction of human absorption using a Caco-2 based penetration assay is routinely performed during drug development. However, the highly variable, rather low expression of P-gp in Caco-2 cells is normally a limiting factor that does not allow the sensitive and reproducible recognition of P-gp substrates [16]. However, for a good drug it has to pass the BBB, human intestinal absorption and Caco2 penetration at the first priority which has satisfied by Apigenin but not with Oseltamivir and Zanamivir. Inhibitory toxicity of drugs was predicted by Toxtree v2.5.0 and admetSAR. Ames Toxicity, mutagenic and carcinogenic properties were predicted. Table 4 (see supplementary material) shows all the three compounds Apigenin, Oseltamivir, and Zanamivir have non-mutagenic or non-carcinogenic properties. Apigenin has showed promising in human intestinal absorption, BBB ability, Caco-2 penetration, solubility and some of the CYP450 substrate and inhibitors, as these factors help in metabolizing and in flushing out the drugs from the body. Apigenin is a flavone class that is aglycone of several naturally occurring glycosides. In in vitro experiments and animal studies, a variety of potential biological activities of Apigenin have been identified [17]. It is used as chemotherapy in autophagy in leukemia cells. It acts as potent inhibitors of CYP2C9 enzyme which is responsible for the metabolism of drugs in the body [18]. In rat model it is used as renal preventive caused by Cyclosporine [19]. In in vitro and in vivo study reveals that Apigenin may stimulate adult neurogenesis and therapeutic potential in rat model [20]. It is one of the active phytocompound derived from Tulsi plant. Tulsi plant is well known for its medical properties. Tulsi plant has shown to its antiviral activity, it may be that Apigenin would be responsible. Considering this, Apigenin can be used as an antiviral drug for swine flu.

Conclusion

Molecular docking of Apigenin with H1N1 proteins shows stronger binding energy having good ADMET property compared to Oseltamivir, and Zanamivir. Therefore, it is of importance to pursue Apigenin as a molecule of interest in this context for further in vitro and in vivo studies.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research, College of Food & Agriculture Science, King Saud University.

Footnotes

Citation:Alhazmi, Bioinformation 11(4): 196-202 (2015)

References

- 1.Collins PJ, et al. Nature. 2008;453:1258. doi: 10.1038/nature06956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das K. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6263. doi: 10.1021/jm300455c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallaher WR. Virol J. 2009;6:51. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison SC, et al. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crusat M, et al. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurib-Fakim A. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:1. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pattanayak P, et al. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:95. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.65323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma V, et al. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research. 2014;5:142. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris GM, et al. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guex N, et al. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trott O, et al. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipinski CA, et al. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pardridge WM. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zlokovic BV. Neuron. 2008;57:178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao YH, et al. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:749. doi: 10.1002/jps.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellinger E, et al. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;41:96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruela-de-Sousa RR, et al. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e19. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Si D, et al. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:629. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong FW, et al. Malays J Pathol. 2009;31:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taupin P, et al. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:523. doi: 10.1517/13543770902721279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.