Abstract

In vitro toxicity assays are efficient and inexpensive tools for screening the increasing number of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) entering the consumer market. However, the data produced by in vitro studies often vary substantially among different studies and from in-vivo data. In part these discrepancies may be attributable to lack of standardization in dispersion protocols and inadequate characterization of particle-media interactions which may affect the particle kinetics and the dose delivered to cells. In this study, a novel approach for preparation of monodisperse, stabilized liquid suspensions was presented and coupled with a numerical model which estimates delivered dose values. Empirically derived material- and media-specific functions were derived for each media- ENM system that can be used to convert administered to delivered doses. The interactions of ENMs with a variety of physiologic media were investigated and the importance of this approach was demonstrated by in vitro cytotoxicity assays using THP-1 macrophages.

Keywords: nanotoxicology, liquid suspension, DLS, dosimetry

1 INTRODUCTION

The physicochemical properties of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) (mobility, quantum size effects, surface area, surface energy) differ substantially from those of the corresponding bulk materials sharing the same chemical composition and atomic structure. These properties endow ENMs with exceptional conductivity, reactivity, and optical sensitivity, and hence superior functionality in a variety of consumer products, including sporting goods, tires, catalysts, microelectronics, cleaners, paints, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. These same properties also result in interactions with biological systems that vary vastly from those of their micron-sized counterparts, which can make them unsafe for humans and for the environment (Nel et al., 2006).

The most common exposure pathways for these ENMs include ingestion (pharmaceutical products, food), dermal contact (occupational exposure, cosmetics), injection (nano-medicines and drug delivery mechanisms), and inhalation (occupational and consumer exposure). These varied exposure pathways each present unique challenges to biological systems, and may result in diverse toxicological outcomes. For example, recent studies suggest that inhaled nanoparticles have the potential to pass from the lungs into the bloodstream and enter extrapulmonary organs, leading to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Choi et al., 2010, Brain, 2009, Mills et al., 2009). Although preliminary evidence demonstrates the potential for ENMs to cause adverse biological effects, the underlying toxicity mechanisms are not currently well understood (Oberdorster, 2007).

A number of studies have endeavored to develop efficient and inexpensive screening tools to correlate mechanisms of biological activity and toxicity with ENM characteristics such as size, shape, and surface area (Rallo et al., 2011, Shaw et al., 2008, Krewski et al., 2010). Due to the high cost and time required for in vivo toxicity studies, most of these efforts have focused on in vitro methods(Lai, 2011, Balbus et al., 2007). High-throughput in vitro toxicity assays have recently been employed to assess multiple toxicity endpoints, in multiple cell lines, of libraries of ENMs over a range of exposure times and concentrations (George, 2011).

In addition to the refinement and standardization of in vitro and in vivo methods, several aspects of the delivery of ENMs in liquid suspension to cultured cells, typical of in vitro toxicity studies, require further analysis. First, commercial ENM nanopowders are limited in diversity of physicochemical and morphological properties (usually to a few sizes for a given composition) making systematic, parametric studies of the relationships between ENM properties (size, surface, composition, shape, charge, etc.) and biological outcomes impossible.

Second, ENMs suspended in culture media may flocculate, agglomerate or dissolve, and interact with serum components (Fadeel, 2010, Jones and Grainger, 2009, Verma and Stellacci, 2010), which can alter their biological properties. More importantly, administered doses may differ substantially from the doses actually delivered to cells. Furthermore, comparison of in vitro doses to those administered by inhalation is difficult, which can result in large differences in effective dose between in vitro and in vivo studies. These limitations may explain some of the disparities reported in the literature between in vivo and in vitro ENM studies (Fadeel, 2010, Fischer and Chan, 2007).

Typical comparisons of biological response to ENM exposure employ administered dose metrics based on the ENM properties as measured in the dry powder form (e.g., mass or surface area per volume), without taking into account particle-particle and particle to physiologic fluid interactions in the suspension liquid suspension (Oberdorster et al., 2005, Jiang, 2008, Rushton et al., 2010, Wittmaack, 2007, Oberdorster et al., 1994). These interactions depend largely upon the dispersion protocol; the particle characteristics, including primary particle size and shape, chemical composition and surface chemistry (Ji et al., 2010, Jiang, 2009, Murdock et al., 2008, Zook et al., 2010); and the liquid media properties such as ionic strength, specific conductance, pH, and protein content ((Lee et al., 2011, Bihari et al., 2008, Elzey, 2009, Murdock et al., 2008, Zook et al., 2010, Wiogo et al., 2011, Laxen, 1977). ENM interactions, in turn, lead to agglomeration in liquid media, which alters the total number of free particles in suspension and the total surface area available for interaction with cells in vitro, as well as the mass transport of ENMs (i.e. sedimentation and diffusion coefficients) which directly impacts delivery of particles to cells (Teeguarden et al., 2007). The importance of such particle dynamics in an in vitro system is demonstrated by the observation that rapidly settling particles elicit cytokine secretion within minutes of application, whereas slow or non-settling particles may take several hours to elicit a similar response (Teeguarden et al., 2007).

Finally, the methods used to disperse nanoparticles in culture media for in vitro studies, which can substantially affect their physical and chemical properties – and hence their biological activities, differ widely between laboratories (Roco, 2010). Clearly a harmonized (standardized and shared) protocol for nanoparticle dispersion is required if the efforts of the many laboratories performing these studies are to produce data that is congruous and cumulative.

In this study, the particle transformations and kinetics of a panel of industrially-relevant ENMs currently under investigation by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (OECD, 2010), and their implications on in vitro dosimetry were investigated. These ENMs were dispersed using a standardized sonication protocol in a variety of typical cell culture media formulations. Empirical functions for converting administered dose to dose delivered to adherent cells in a 96-well microplate format were derived for a variety of commonly used metal oxide ENMs dispersed in physiological fluids including cell culture media with or without either fetal bovine serum or serum albumin. The proposed standardized dispersion protocol and empirical dose metric functions reported herein may be useful for in vitro nanotoxicity studies, enabling consistent, reproducible preparations of stabilized, monodisperse ENM suspensions and reliable estimates of the particle dose delivered to cells as a function of time. The utility of this approach on in vitro nanotoxicity studies was demonstrated using adherent PMA-matured THP-1 macrophage cells and a standard fluorescence microscopy-based live/dead cytotoxicity assay.

2 EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1 Nanomaterials and characterization of ENM powders

ENMs investigated in this study are listed in Table 1. ENMs included both commercially available and in-house generated ENMs of varied composition, surface chemistry, and primary particle size. In-house particles were generated using the Harvard Versatile Engineered Nanomaterial Generation System (VENGES), as previously described (Demokritou et al., 2010, Sotiriou et al., 2011)

Table 1.

ENM powder properties. SSA: (specific surface area) by nitrogen adsorption/Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method. dBET : particle diameter determined from SSA and particle density, ρ, as described in methods. dXRD : particle diameter by X-ray diffraction.

| Material | SSA (m2/g) | dBET (nm) | dXRD (nm) | ρ (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VENGES SiO2 |

231 | 11.8 | NA | 2.2 |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2* |

200 | 9.9 | 6 (75 wt%)** 27(25 wt%) |

3.029 |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2* |

375 | 5.3 | 6.9 | 3.029 |

| VENGES 2Ag/SiO2* |

350 | 5.7 | NA | 2.365 |

| VENGES 25Ag/SiO2* |

290 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 4.272 |

| VENGES CeO2 |

152 | 13 | 9 | 7.65 |

| VENGES CeO2 |

66 | 30 | 20 | 7.65 |

| VENGES Fe2O3 |

239 | 4.8 | 2(95 wt%)** 30(5 wt%) |

5.242 |

| EVONIK SiO2 |

200 | 14 | NA | 2.2 |

| EVONIK SiO2 |

50 | 55 | NA | 2.2 |

| EVONIK TiO2 |

50 | 21 | 33 | 4.23 |

Note:

denotes composite material XAg/SiO2, where X is equal to the mass percentage of Ag deposited onto SiO2 particles.

denotes crystal size measured by x-ray diffraction is bimodal

Specific surface area, SSA, defined as the area per mass (m2/g), was determined by the nitrogen adsorption/Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method (Micrometrics Tristar Norcross, GA, USA). The equivalent primary particle diameter, dBET, was calculated, assuming spherical particles, as:

| (1) |

where ρp is the particle density, which was obtained for each particle from the densities of component materials, at 20°C, reported in the CRC handbook of Chemistry and Physics (CRC, 2010).

Particle diameter was also determined by X-ray diffraction and reported as dXRD (nm). Particle morphology and size were further characterized by scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM/TEM).

2.2 ENM dispersal and characterization in liquid suspensions

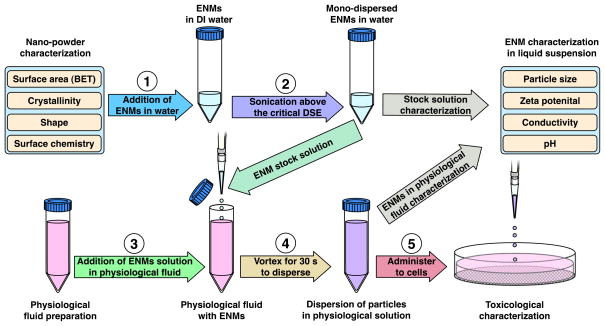

ENM dispersion was performed using a protocol based on those established by OECD and NIST (OECD, 2010, Taurozzi, 2010), including calibration of sonication equipment to ensure accurate application and reporting of delivered sonication energy (DSE) in J/ml (Taurozzi et al., 2010). This protocol included identification and subsequent utilization of the material-specific critical sonication energy required to achieve monodisperse solutions at the lowest agglomeration state, as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Probe sonication was performed in deionized water (DI H2O) to minimize reactive oxygen species generation via sonolysis, to minimize ionic strength and specific conductance, and hence particle interactions, during sonication, and to avoid denaturation of proteins in the final cell delivery media. Stock solutions were then diluted in various physiological fluids prior to characterizion for various particle and media parameters, or application to cells for toxicological evaluation. The dispersal protocol is illustrated schematically in Figure 1, and is described in detail in the following sections:

Figure 1.

Characterization and dispersion protocol.

Sonication and Critical DSE determination

The critical DSE (DSEcr) of an ENM is defined as the delivered sonication energy (in J/ml) required to achieve a monodisperse solution at the lowest particle agglomeration state in deionized water. The DSEcr was determined for each ENM as follows. ENMs were dispersed at 1 mg/ml in 10 ml of solute in 50 ml, 24 mm diameter conical polyethylene tubes, by sonication with a Branson Sonifier S-450A (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) fitted with a flat tip 1/8 inch probe (maximum power output of 400 W at 60 Hz, continuous mode, output level 1. The probe tip was immersed to a depth of 5 cm in the sample suspension, and the sample tube was bathed in ice during sonication (except during calibration) to minimize heating of the particles. The system was calibrated by the calorimetric calibration method described by Taurozzi (Taurozzi et al., 2010), whereby the power delivered to the sample was determined to be 3.14 W. The delivered sonication energy (DSE) was determined from the calibrated delivered power over a range of sonication times. Dispersions were analyzed for hydrodynamic diameter (dH), polydispersity index (PdI), zeta potential (ζ), and specific conductance (σ) by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). Plots of hydrodynamic diameter as a function of DSE exhibiting asymptotic de-agglomeration trends were derived for each ENM and used to determine the material specific DSEcr, corresponding to the lowest agglomeration state (minimum dH).

Preparation of ENM dispersions in physiological media

For each ENM, a stock solution of 1mg/ml was prepared by sonicating the ENM powder in DI H2O as described above for a time corresponding to the material-specific DSEcr. The stock solution was then diluted in either RPMI alone, RPMI + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), or RPMI + 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) to the final concentration (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100μg/ml), and vortexed for 30 seconds. ENM dispersions in media were analyzed by DLS as described above. pH was measured using a VWR sympHony pH meter (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA).

2.3 Dose calculations

All dose calculations were based on a media volume, V, of 0.1 ml, and mass concentration, γ, of 50 μg/ml.

Administered dose calculation

Administered mass dose, MA (μg), was calculated as:

| (1) |

where γA is the mass concentration (μg/ml), and V is the volume of media (ml).

Administered particle number dose, NA (#), was calculated from MA, hydrodynamic radius, rH (nm, determined by DLS for ENMs in suspension), and material density, ρ, (g/cm3, assuming spherical, non porous agglomerates with densities equal to those of the corresponding original particles) as:

| (2) |

Administered surface area dose, SAA (cm2), was calculated as:

| (3) |

Delivered dose (DD) calculation

Delivered doses in terms of mass, MD, number of particles, ND, and surface area, SAD, were calculated from administered doses as:

| (4) |

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

where fD(t) is defined as the fraction of administered particles deposited at time t, onto adherent cells at the bottom of a cell culture well.

Calculation of deposited fractions fD(t)

The in vitro sedimentation, diffusion and dosimetry (ISDD) model proposed by Hinderliter et. al. (Hinderliter et al., 2010) was used to calculate numerically, for each ENM-media combination, the fraction of administered particles that would be deposited onto cells as a function of time fD(t). The particle hydrodynamic diameter, dH, as measured by DLS and listed in Table 2 was used as input to the model. Additionally, the following parameters were used as input to the ISDD numerical model: Media column height, 3.3 mm; temperature, 310K; media density, 1.00 g/ml; viscosity, 0.00069 Pa s for RPMI and 0.00074 Pa s for RPMI/10%FBS and RPMI/1%BSA (Hinderliter et al., 2010); administered (initial suspension) particle concentration, 50 μg/ml; particle density, as listed in Table 1.

Table 2.

ENM Critical DSE

| Material | DSEcr (J/ml) |

|---|---|

| VENGES SiO2 dBET=11.9nm |

161 |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 d BET =9.9nm |

242 |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 d BET =5.3nm |

242 |

| VENGES 2Ag/SiO2 d BET =5.7nm |

242 |

| VENGES 25Ag/SiO2 d BET=6.8nm |

242 |

| VENGES CeO2 dBET=13nm |

242 |

| VENGES CeO2 dBET=30nm |

242 |

| VENGES Fe2O3 dBET=4.8nm |

242 |

| EVONIK SiO2 dBET=14nm |

161 |

| EVONIK SiO2 dBET=55nm |

161 |

| EVONIK TiO2 dBET=25nm |

161 |

For each ENM-media combination, the model-derived fD (t) was fit to a Gompertz sigmoidal equation as follows:

| (7) |

where t is time (h), and α is a particle- and media-specific deposition fraction constant (h−1). The deposition fraction constant α (h−1) was calculated for each ENM-media combination.

Solving Equation 7 for the time t at which the fraction fD(t) of administered particles is delivered yields:

| (8) |

Equation 8 was used to calculate the time required for delivery of 99% of the administered dose, t99, for each ENM-media combination using the specific deposition function constants, α, and an fD(t) value of 0.99.

2.4 In vitro toxicity assessment

RPMI, calcein AM, ethidium homodimer-1, Hoechst-33342, and HCS CellMask Blue were obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Penicillin/Streptomycin, HEPES and BSA were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and FBS and heat-inactivated FBS were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Atlanta, GA). All incubations were performed at 37°C/5% CO2 unless otherwise specified. Assays were repeated three times for each ENM.

THP-1 monocytes were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 mM HEPES. THP-1 cells were matured according to the method described by Daigneault et. al. (Daigneault et al., 2010) as follows: Cells were resuspended at a 3.2 × 105/ml in RPMI/10%FBS containing 200 nM PMA, dispensed into 96-well black-walled imaging plates (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 8.0 × 105cells/well in culture media with 200 nM PMA, incubated for 3 days, washed with PBS, and incubated for an additional 5 days in RPMI/10% FBS (without PMA).

PMA-matured THP-1 macrophages were incubated for either 4 or 24 hours with 100 μl/well of ENM dispersions at varied concentrations between 0.0 and 50.0 μg/ml in either RPMI alone, RPMI + 1%BSA or RPMI+10%FBS. Following ENM exposure cells were washed with HBSS, incubated for 30 min. with 1.0 μM CalceinAM, 2.0 μM ethidium homodimer-1, 2.0 μg/ml Hoechst 33342, and 2.5 μg/ml HCS CellMask Blue in HBSS, and finally covered with PBS.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy was performed using a BD Pathway 855 High-Content Bioimager with a 20X NA075 objective (Olympus), with laser auto-focus, 2×2 binning and flat field correction. Green channel images (calceinAM) were acquired using 470/40 band-pass (BP) excitation, 515 long-pass (LP) dichroic and 515 LP emission filters, red channel images (ethidium homodimer-1) using 560/20 BP excitation, 595 LP dichroic and 645 LP emission filters, and blue channel images (Hoechst/CellMask Blue) using 350/20 BP excitation, 400 LP dichroic, and 435 LP emission filters. Three non-overlapping 20X image fields were acquired for each well to produce a total of six sets of images (3 fields x duplicate wells) per condition.

Image analysis and quantification was performed using custom software developed in MATLAB ® (The Mathworks, Natick, MA). Individual cells were identified in Hoechst/CellMask Blue images (blue channel) by watershed segmentation as previously described (DeLoid et al., 2009, Sulahian et al., 2008). Viable cells were identified based on green (calceinAM) and red (ethidium homodimer-1) image channel pixel values corresponding to each set of cell pixels. A threshold for calceinAM images, below which cell pixels were categorized as calcein negative, was selected as the minimum pixel grayscale value at which all brightly staining cells were positive. The threshold for ethidium homodimer-1, above which cell pixels were categorized as ethidium-homodimer-1 positive, was selected as the maximum grayscale value at which only pixels within brightly stained nuclei were positive. Threshold values were maintained throughout analysis of all experiments with all ENMs. Cells in which more than 50% of pixels were calceinAM positive, and in which less than 5% of pixels were ethidium homodimer-1 positive, were scored by the software as viable. All other cells were scored as non-viable. The total number of viable and non-viable cells for each treatment/media combination was obtained by summing viable and non viable cell counts for the three fields in each of the duplicate wells.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characterization of raw ENM powders

The panel of ENMs investigated in this study consisted of industry-relevant metal oxides of varied primary particle sizes, shapes and surface chemistries. ENM properties in powder form are summarized in Table 1 and include SSA, dBET and dXRD. In addition, as shown in the representative TEM/SEM images in Figure S-1, these ENMs appeared to form chain-like aggregates in nanopowder form.

3.2 Characterization of ENM liquid suspensions – Dispersion Protocol

Critical DSE

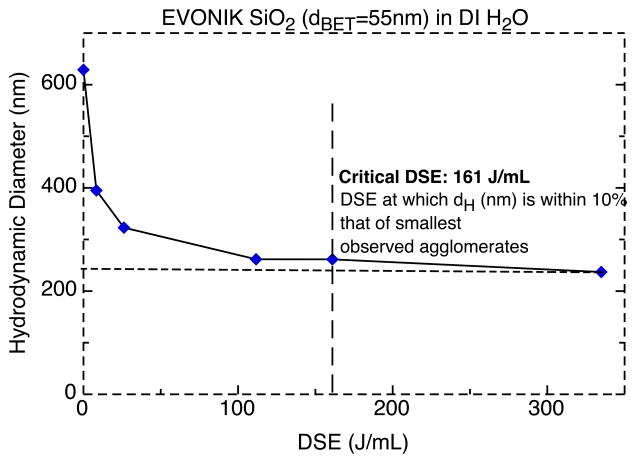

For each ENM, the DLS determined hydrodynamic diameter (dH) was plotted as a function of the DSE. For all ENMs, dH decreased with increasing DSE toward a horizontal asymptote, representing a minimal agglomeration state. From each curve, an ENM-specific DSEcr was estimated by determining the DSE value at which the dispersed ENMs were within 10% of their observed minimum dH value.(theoretical dH at DSE = +∞). An example of the aforementioned asymptotic curve and its estimated DSEcr for SiO2 (EVONIK, dBET= 55 nm) is shown in Figure 2. Table 2 summarizes the estimated DSEcr for all investigated ENMs. DSEcr values varied from 161 to 242 J/ml, and required between 8.5 and 12 minutes with the Branson 450 analog sonicator at the settings described in methods (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Hydrodynamic diameter as a function of DSE for EVONIK SiO2 (dBET=55nm). Critical DSE: energy required for minimal agglomeration.

In order to validate the reproducibility of our calorimetric calibration and estimation of DSEcr, calibration, sonication and DLS analysis were performed with a second sonicator (Vibra-Cell VCX 130, Sonics and Materials, Inc. Newtown, CT). The Vibra-Cell model yielded agglomeration sizes and DSEcr values (data not shown) for various ENMs consistent with those obtained using the Branson 450 sonicator (data not shown), verifying that the proposed calorimetric approach for the precise estimation of DSE, enables reproducible results with different sonicators (Taurozzi et al., 2010).

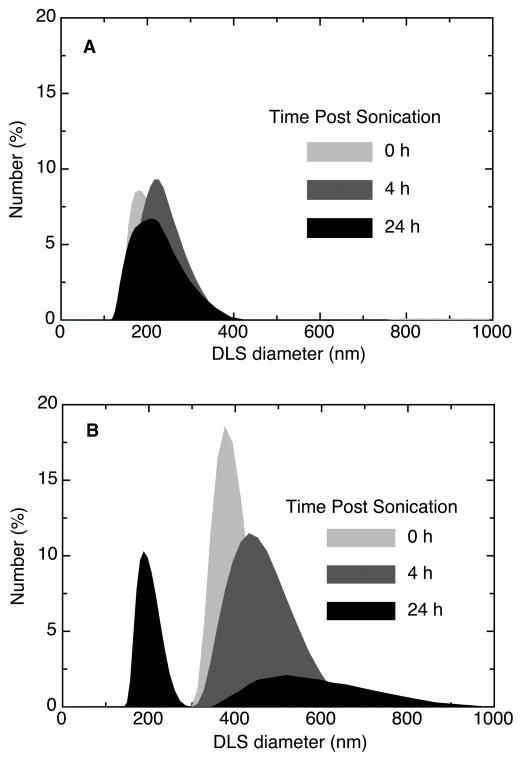

Dispersion stability over time

The size distribution (by DLS) of dispersions created at and below DSEcr, of a representative ENM dispersion (EVONIK SiO2, dBET=55nm) over a 24-hour period are shown in Figure 3. Dispersion at the DSEcr (161 J/ml, Figure 3A) produced a monodisperse suspension of small agglomerates. In contrast, sonication below the DSEcr (9 J/ml, Figure 3B) produced polydisperse suspensions of significantly larger agglomerates. In addition to achieving minimal agglomeration, sonication at the DSEcr also produced dispersions with stable size distributions, whereas the size distribution of dispersions generated below DSEcr changed substantially over time (Figure 3A and 3B). Similar results were obtained for all other ENMs investigated in this study (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution for dispersions of SiO2 (dBET=55nm) in RPMI at various time points and DSE levels; A. sonication at the critical DSE (161 J/ml), B. sonication below critical DSE (9 J/ml).

Agglomeration in physiological fluids

Measured properties of ENM dispersions (hydrodynamic diameter (dH), polydispersity index (PdI), zeta potential (ζ), and specific conductance (σ), in DI H2O and the three media formulations studied are summarized in Table 3. In general, dH, PdI, and ζ were both material- and media-specific. The pattern of agglomerate sizes in the various dispersion media differed qualitatively between ENMs with negative ζ values and those with positive ζ values in DI H2O. ENMs with negative ζ values in DI H2O (SiO2 and Ag/SiO2 ENMs) formed much larger agglomerates in media containing 10% FBS, than in either RPMI alone, RPMI with 1%BSA or DI H2O. In contrast, materials with positive ζ values in DI H2O (Fe2O3, CeO2, TiO2) formed markedly larger agglomerates (up to micron scale) in RPMI alone, intermediate-sized agglomerates in RPMI containing either 1%BSA or 10%FBS, and smaller agglomerates in DI H2O.

Table 3.

Properties of ENM dispersions. dH: hydrodynamic diameter, PdI: polydispersity index, ζ: zeta potential, σ: specific conductance

| Material | Media | dH (nm) | PdI | ζ (mV) | σ (mS/cm) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VENGES SiO2 dBET=11.9nm |

DI H2O | 124 ± 7.19 | 0.188 ± 0.013 | −22.1 ± 1.04 | 0.0102 ± 0 | 6.05 ± 0.46 |

| RPMI | 115 ± 2.40 | 0.273 ± 0.025 | −25.4 ± 2.00 | 10.4 ± 0.29 | 7.77 ± 0.12 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 204 ± 13.5 | 0.542 ± 0.004 | −12.3 ± 0.066 | 12.1 ± 0.033 | 8.05 ± 0.13 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 144 ± 5.59 | 0.653 ± 0.032 | −14.6 ± 0.20 | 11.2 ± 0.088 | 7.85 ± 0.082 | |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 dBET=9.9nm |

DI H2O | 198 ± 9.08 | 0.256 ± 0.004 | −33.4 ± 6.64 | 0.0097 ± 0.002 | 7.35 ± 0.13 |

| RPMI | 158 ± 5.29 | 0.365 ± 0.017 | −27.7 ± 0.75 | 11.3 ± 0.066 | 8.43 ± 0.15 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 220 ± 29.3 | 0.453 ± 0.084 | −11.5 ± 0.17 | 11.3 ± 0.033 | 8.46 ± 0.22 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 155 ± 21.4 | 0.656 ± 0.18 | −13.8 ± 1.60 | 9.66 ± 0.64 | 8.21 ± 0.19 | |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 dBET=5.3nm |

DI H2O | 133 ± 2.33 | 0.353 ± 0.029 | −24.5 ± 0.72 | 0.0359 ± 0 | 8.55 ± 0.21 |

| RPMI | 157 ± 18.1 | 0.287 ± 0.025 | −21.7 ± 0.67 | 10.9 ± 0.15 | 8.28 ± 0.073 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 427 ± 73.3 | 0.594 ± 0.102 | −9.8 ± 0.20 | 10.8 ± .13 | 8.33 ± 0.10 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 121 ± 56.5 | 0.548 ± 0.061 | −13.3 ± 0.84 | 12.8 ± 0.28 | 8.26 ± 0.12 | |

| VENGES 2Ag/SiO2 dBET=5.7nm |

DI H2O | 137 ± 0.76 | 0.31 ± 0.0011 | −25.2 ± 0.55 | 0.0151 ± 0 | 7.9 ± 0.084 |

| RPMI | 301 ± 17.6 | 0.392 ± 0.036 | −24.6 ± 0/24 | 11 ± 0.10 | 8.43 ± 0.10 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 516 ± 11.3 | 0.511 ± 0.055 | −10.7 ± 0.058 | 10.4 ± 0.22 | 8.42 ± 0.091 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 149 ± 11.3 | 0.509 ± 0.087 | −13.4 ± 0.44 | 12.7 ± 0.15 | 8.34 ± 0.082 | |

| VENGES 25Ag/SiO2 dBET=6.8nm |

DI H2O | 122 ± 1.14 | 0.396 ± 0.005 | −24.8 ± 1.43 | 0.0487 ± 0.004 | 9.13 ± 0.11 |

| RPMI | 198 ± 9.22 | 0.4 ± 0.011 | −26.8 ± 0.87 | 12.9 ± 0.33 | 8.29 ± 0.12 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 310 ± 13.9 | 0.488 ± 0.040 | −14.5 ± 4.62 | 9.41 ± 0.26 | 8.03 ± 0.079 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 156 ± 17.2 | 0.449 ± 0.064 | −15.5 ± 0.033 | 11.5 ± 0.066 | 8.19 ± 0.10 | |

| VENGES CeO2 dBET=13nm |

DI H2O | 136 ± 0.404 | 0.362 ± 0.005 | 35.5 ± 1.00 | 0.0123 ± 0 | 5.56 ± 0.089 |

| RPMI | 1678 ± 260 | 0.475 ± 0.053 | −10.1 ± 0.239 | 11.1 ± 0.12 | 7.92 ± 0.087 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 235 ± 5.92 | 0.253 ± 0.010 | −14.3 ± 0.433 | 10.4 ± 0.057 | 8.16 ± 0.098 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 369 ± 6.46 | 0.338 ± 0.0138 | −15.4 ± 0.583 | 11.4 ± 0.133 | 7.95 ± 0.079 | |

| VENGES CeO2 dBET=30nm |

DI H2O | 127 ± 16.4 | 0.353 ± 0.110 | 34.5 ± 3.15 | 0.022 ± 0 | 7.4 ± 0.04 |

| RPMI | 1376 ± 371 | 0.149 ± 0.130 | −9.77 ± 0.497 | 11 ± 0.152 | 7.95 ± 0.069 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 227 ± 3.25 | 0.243 ± 0.0132 | −12.0 ± 0.329 | 11.9 ± 0.0883 | 8.19 ± 0.073 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 552 ± 37.3 | 0.406 ± 0.120 | −14.7 ± 0.408 | 10.7 ± 0.490 | 7.94 ± 0.065 | |

| VENGES Fe2O3 dBET=4.8nm |

DI H2O | 151 ± 9.14 | 0.449 ± 0.016 | 27.8 ± 2.42 | 0.0148 ± 0.002 | 7.03 ± 0.088 |

| RPMI | 4333 ± 400 | 0.357 ± 0.020 | −16.7 ± 0.23 | 11 ± 0.12 | 8.45 ± 0.094 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 226 ± 4.20 | 0.213 ± 0.014 | −13.4 ± 0.60 | 11.4 ± 0.033 | 8.46 ± 0.11 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 937 ± 104 | 0.612 ± 0.069 | −15.6 ± 0.93 | 11.4 ± 0.32 | 7.74 ± 0.086 | |

| EVONIK SiO2 dBET=14nm |

DI H2O | 166 ± 4.27 | 0.195 ± 0.040 | −36.3 ± 2.79 | 0.0239 ± 0 | 7.23 ± 0.079 |

| RPMI | 147 ± 0.78 | 0.122 ± 0.008 | −32.2 ± 0.0019 | 11.8 ± 0.29 | 8.43 ± 0.098 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 227 ± 2.50 | 0.302 ± 0.002 | −12.2 ± 0.25 | 11.3 ± 0.17 | 8.43 ± 0.081 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 210 ± 0.90 | 0.738 ± 0.038 | −15.6 ± 0.49 | 11 ± 0.18 | 8.19 ± 0.11 | |

| EVONIK SiO2 dBET=55nm |

DI H2O | 262 ± 2.42 | 0.16 ± 0.0029 | −38.6 ± 0.19 | 0.00867 ± 0 | 7.18 ± 0.075 |

| RPMI | 244 ± 1.83 | 0.165 ± 0.008 | −36.5 ± 1.77 | 11.1 ± 0.26 | 8.38 ± 0.077 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 277 ± 32.7 | 0.474 ± 0.021 | −12.7 ± 0.066 | 11.8 ± 0.12 | 8.36 ± 0.080 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 290 ± 11.0 | 0.475 ± 0.046 | −16.6 ± 0.57 | 12.3 ± 0.15 | 8.14 ± 0.074 | |

| EVONIK TiO2 dBET=25nm |

DI H2O | 241 ± 6.37 | 0.209 ± 0.011 | 25.8 ± 3.82 | 0.0368 ± 0.005 | 7.28 ± 0.19 |

| RPMI | 2867 ± 74.8 | 0.194 ± 0.043 | −11.4 ± 0.351 | 12.5 ± 0.18 | 8.47 ± 0.13 | |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 471± 0.97 | 0.193 ± 0.028 | −10.9 ± 0.55 | 10.5 ± 0.42 | 8.45 ± 0.11 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 408 ± 14.4 | 0.196 ± 0.022 | −6.75 ± 3.30 | 4.56 ± 3.27 | 8.33 ± 0.099 |

3.3 Dosimetry analysis and empirical deposition fractions, fD(t)

Administered dose

Total administered mass, MA, surface area, SAA, and particle number, NA, doses for each ENM-media system are summarized in Table 4. Note that since NA is inversely proportional to rH3(Equation 2), larger agglomerates in the dispersions result in much smaller administered numbers of particles. Furthermore, since SAA is proportional to rH2 × NA (Equation 3), or rH2/3, larger agglomerates in the dispersion are associated with smaller administered surface area values, for a given administered mass dose. For example, the approximately 3.5 fold larger agglomerate size, as indicated by the DLS-determined rH, for the RPMI/10%FBS media, compared with that observed in RPMI alone, for VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm), is accompanied by a roughly 20 fold lower NA (4.05E+07 vs. 8.08E+08), and a 2.7 fold lower SAA (0.231 cm2 vs. 0.629 cm2).

Table 4.

Administered doses. Total surface area (SAA), and particle number (NA) were calculated using Equations 1–3 and the estimated agglomerate density (ρa), for a volume, V, of 0.1 ml, a mass concentration, γA, of 50 μg/ml, and total mass of 5 μg, with particle radius, r, set to the particle agglomerate hydrodynamic radius (rH = dH/2) obtained from DLS for each of the three media formulations.

| Material | Media | ρa (g/cm3) | rH (nm) | SAA (cm2) | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VENGES SiO2 dBET=11.9nm |

RPMI | 1.07 | 57.3 | 2.45 | 5.95E+09 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.03 | 103 | 1.42 | 1.09E+09 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.05 | 71.9 | 1.98 | 3.05E+09 | |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 dBET=9.9nm |

RPMI | 1.29 | 78.8 | 1.47 | 1.89E+09 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.23 | 110 | 1.10 | 7.25E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.30 | 77.4 | 1.50 | 1.99E+09 | |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 dBET=5.3nm |

RPMI | 1.19 | 78.7 | 1.60 | 2.06E+09 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.09 | 214 | 0.642 | 1.12E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.23 | 60.8 | 2.01 | 4.34E+09 | |

| VENGES 2Ag/SiO2 dBET=5.7nm |

RPMI | 1.08 | 150 | 0.920 | 3.24E+08 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.06 | 258 | 0.549 | 6.55E+07 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.14 | 74.7 | 1.76 | 2.52E+09 | |

| VENGES 25Ag/SiO2 dBET=6.8nm |

RPMI | 1.31 | 99.0 | 1.16 | 9.41E+08 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.23 | 105 | 1.16 | 8.39E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.37 | 77.9 | 1.41 | 1.85E+09 | |

| VENGES CeO2 dBET=13nm |

RPMI | 1.22 | 839 | 0.146 | 1.66E+06 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.88 | 117 | 0.680 | 3.94E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.64 | 185 | 0.496 | 1.16E+08 | |

| VENGES CeO2 dBET=30nm |

RPMI | 1.46 | 688 | 0.150 | 2.52E+06 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 2.61 | 114 | 0.953 | 5.89E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.87 | 276 | 0.291 | 3.04E+07 | |

| VENGES Fe2O3 dBET=4.8nm |

RPMI | 1.04 | 2167 | 0.0668 | 1.13E+05 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.29 | 113 | 1.03 | 6.48E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.11 | 469 | 0.289 | 1.05E+07 | |

| EVONIK SiO2 dBET=14nm |

RPMI | 1.37 | 73.3 | 1.49 | 2.22E+09 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.30 | 114 | 1.02 | 6.27E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.31 | 105 | 1.09 | 7.92E+08 | |

| EVONIK SiO2 dBET=55nm |

RPMI | 1.42 | 122 | 0.864 | 4.62E+08 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.39 | 139 | 0.780 | 3.23E+08 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.38 | 145 | 0.752 | 2.84E+08 | |

| EVONIK TiO2 dBET=25nm |

RPMI | 1.10 | 1434 | 0.0949 | 3.67E+05 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1.37 | 236 | 0.466 | 6.68E+07 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 1.40 | 204 | 0.523 | 9.99E+07 |

Delivered dose- empirical deposition fraction equations

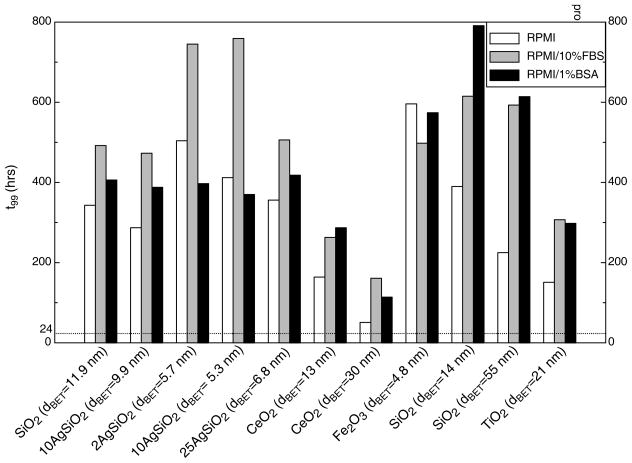

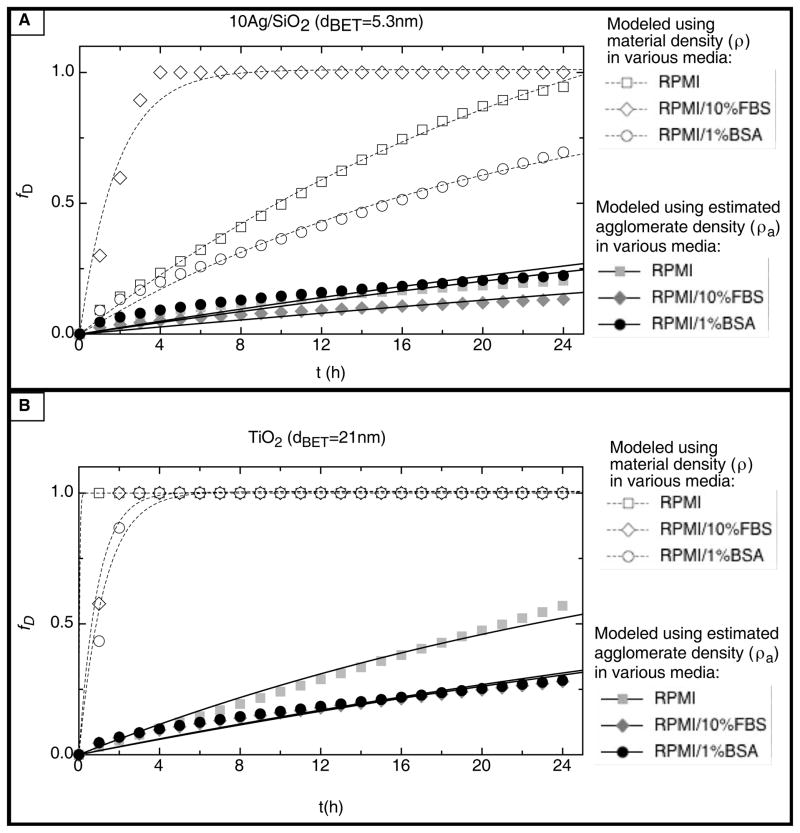

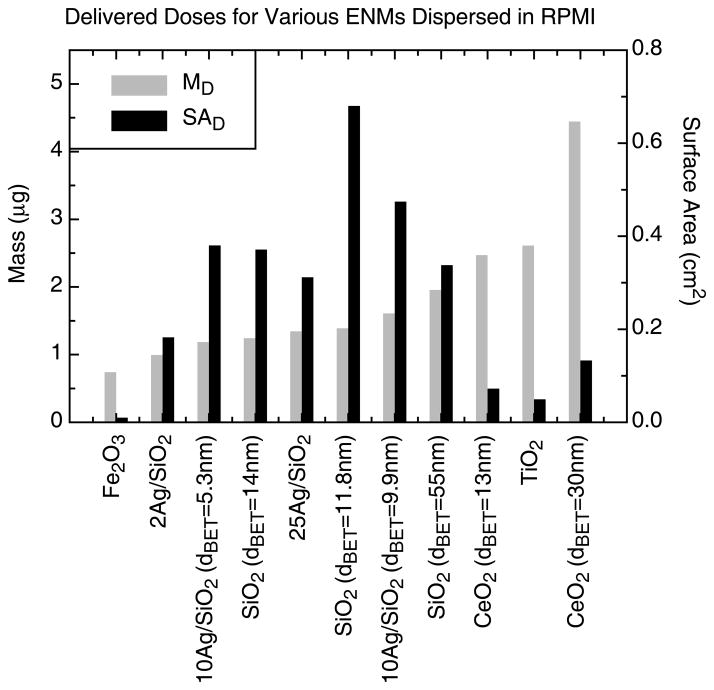

The particle- and media-specific deposition fraction constant, α(h−1), and the time required to deliver 99% of the administered dose to cells, t99 (h), for each ENM-media system, are summarized in Table 5 and Figure 4. In addition, representative deposition fraction curves for 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm), SiO2 (dBET=11.9nm), TiO2 (dBET=25nm), and CeO2 (dBET=30nm) in each media formulation are presented in Figure 5. Notably, both the deposition fraction curve shape, deposition fraction constant α, and t99, were greatly influenced by material density. Materials of relatively high density, such as TiO2 (ρ=4.23g/cm3), and CeO2 (ρ=7.65g/cm3) had relatively steep deposition fraction curves and corresponding large α values, as well as relatively short t99 times, compared to materials of lower density such as SiO2 (ρ=2.2g/cm3) (Table 5, Figure 4, Figure 5).

Table 5.

Deposition fraction constant, α (h−1), and time for delivery of 50% of dose, t50 (h), and 99% of dose, t99 (h), for each ENM-media system.

| Material | Media | dH (nm) | α (h−1) | t50 (h) | t99 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VENGES SiO2 (dBET =11.9nm) |

RPMI | 115 ± 2.40 | 0.0136 | 51.1 | 343 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 204 ± 13.5 | 0.00945 | 73.3 | 492 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 144 ± 5.59 | 0.0115 | 60.5 | 406 | |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=9.9nm) |

RPMI | 158 ± 5.29 | 0.0162 | 42.8 | 287 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 220 ± 29.3 | 0.00984 | 70.4 | 473 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 155 ± 21.4 | 0.0120 | 57.9 | 388 | |

| VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm) |

RPMI | 157 ± 18.1 | 0.0113 | 61.4 | 412 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 427 ± 73.3 | 0.00612 | 113 | 759 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 122 ± 56.5 | 0.0125 | 55.2 | 370 | |

| VENGES 2Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.7nm) |

RPMI | 301 ± 17.6 | 0.00923 | 75.1 | 504 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 516 ± 11.3 | 0.00624 | 111 | 745 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 149 ± 11.3 | 0.0117 | 59.1 | 397 | |

| VENGES 25Ag/SiO2 (dBET=6.8nm) |

RPMI | 198 ± 9.22 | 0.0131 | 53.0 | 356 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 310 ± 13.9 | 0.00918 | 75.5 | 506 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 156 ± 17.2 | 0.0111 | 62.3 | 418 | |

| VENGES CeO2 (dBET=13nm) |

RPMI | 1678 ± 260 | 0.0284 | 24.4 | 164 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 235 ± 5.92 | 0.0177 | 39.3 | 263 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 369 ± 6.46 | 0.0162 | 42.8 | 287 | |

| VENGES CeO2 (dBET=30nm) |

RPMI | 1376 ± 371 | 0.0916 | 7.57 | 50.8 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 227 ± 3.25 | 0.0289 | 24.0 | 161 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 552 ± 37.3 | 0.0407 | 17.0 | 114 | |

| VENGES Fe2O3 (dBET=4.8nm) |

RPMI | 4333 ± 400 | 0.00669 | 104 | 695 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 226 ± 4.20 | 0.00933 | 72.3 | 498 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 937 ± 104 | 0.00810 | 85.5 | 574 | |

| EVONIK SiO2 (dBET=14nm) |

RPMI | 147 ± 0.78 | 0.0119 | 58.2 | 390 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 227 ± 2.50 | 0.00755 | 91.7 | 615 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 210 ± 0.90 | 0.00588 | 118 | 791 | |

| EVONIK SiO2 (dBET=55nm) |

RPMI | 244 ± 1.83 | 0.0207 | 33.5 | 225 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 277 ± 32.7 | 0.00784 | 88.4 | 593 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 290 ± 11.0 | 0.00758 | 91.5 | 614 | |

| EVONIK TiO2 (dBET =21nm) |

RPMI | 2867 ± 74.8 | 0.0308 | 22.5 | 151 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 471 ± 0.97 | 0.0151 | 45.8 | 307 | |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 408 ± 14.4 | 0.0156 | 44.5 | 298 |

Figure 4.

Time to deliver 99% of administered dose to cells (t99) for each ENM-media combination.

Figure 5.

Fraction of administered dose deposited, fD, as a function of t (h) for various ENMs in the three media formulations; A. VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm); B. VENGES SiO2 (dBET=11.9nm); C. EVONIK TiO2 (dBET=25nm); D. VENGES CeO2 (dBET=30nm).

It is also clear that deposition kinetics are greatly dependent on dispersion media and the associated material agglomeration states. For example, the delivery of 10Ag/SiO2 to cells in media containing FBS, in which particles exist in relatively large agglomerates (larger dH), occurs at a much faster rate (large α and short t99), than in RPMI alone or in RPMI with 1%BSA (Table 5, Figure 4, Figure 5).

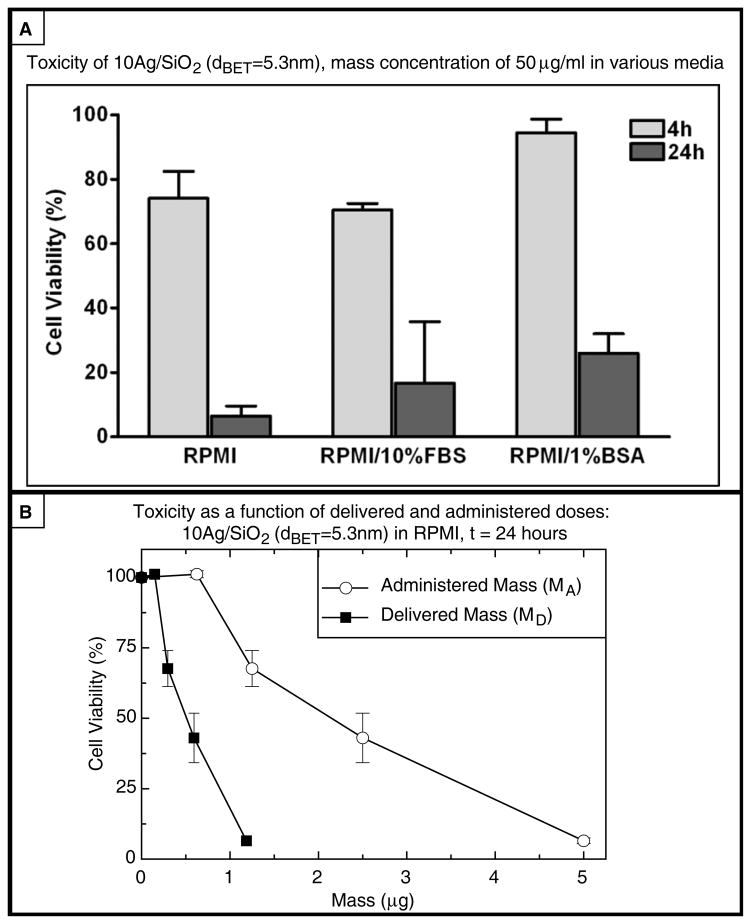

3.4 In vitro cytotoxicity of ENM suspensions

In order to assess the roles of ENM property transformations and deposition kinetics in ENM-cell interactions and biological effects, in vitro cytotoxicity in adherent PMA-matured THP-1 macrophages was evaluated over a range of administered and delivered doses for ENMs in each of the three media formulations, at 4 and 24 hours. Cell viability following exposure to 50 μg/ml 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm) in each media type, for 4 and 24 hours, is depicted in Figure 6. Cell viability is also presented alongside corresponding administered and delivered dose metric values for each exposure time in Table 6. Toxicity data were collected and analyzed for all other ENM-media combinations, various doses and exposure times and will be presented by the authors in a forthcoming manuscript.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity of VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm) at 4 and 24 h in the three media formulations at a mass concentration of 50μg/ml.

Table 6.

Summary of administered doses, delivered doses and cytoxicity for 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm) dispersed in each media formulation (0.1 ml at 50 μg/ml, administered mass dose, MA, = 5.0 μg).

| Media | SAA (cm2) | NA | 4 Hours | 24 Hours | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (μg) | SAD (cm2) | ND | Cell Viability (%) | MD (μg) | SAD (cm2) | ND | Cell Viability (%) | |||

| RPMI | 1.60 | 2.06E+09 | 0.221 | 0.0707 | 9.09+07 | 74.1 | 1.19 | 0.380 | 4.89E+08 | 6.49 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 0.642 | 1.12E+08 | 0.121 | 0.0154 | 2.71E+06 | 70.5 | 0.683 | 0.0878 | 1.53E+07 | 16.6 |

| RPMI/1%BSA | 2.01 | 4.34E+09 | 0.245 | 0.0986 | 2.12E+08 | 94.4 | 1.30 | 0.523 | 1.13E+09 | 26.0 |

Although 1-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences between percent viability of cells treated with 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm) in the three different media formulations at four hours (overall p < 0.05), neither Tukey’s nor Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests identified significant differences in cytotoxicity within any pair of dispersal medias. Nevertheless, particles dispersed in RPMI/10%FBS appeared to be more toxic than those dispersed in either RPMI alone, or RPMI/1% BSA. For an identical administered mass dose (MA = 5.0 μg), the administered surface and number doses were substantially lower in RPMI/10% FBS (SAA = 0.231 cm2, NA = 4.05E+07) than in either RPMI alone (SAA = 0.629 cm2, NA = 8.08E+08) or in RPMI/1% BSA (SAA = 0.815 cm2, NA = 1.76E+09). In contrast, however, the delivered surface dose at 4 hours was greater for particles in RPMI/10%FBS (SAD = .205 cm2) than for cells in either RPMI alone (SAD = .087 cm2) or in RPMI/1% BSA (SAD = .140 cm2), and delivered mass dose was markedly greater in RPMI/10% FBS (MD= 4.440 g) than in RPMI alone (MD = 0.691 g) or with 1% BSA (MD = 0.859 g), consistent with the higher cytotoxicity observed with particles dispersed in RPMI/10%FBS. No significant differences were detected by 1-way ANOVA, between viability of cells treated for 24 hours in the different media formulations, although a similar trend was observed, consistent with the same relative differences in administered and delivered surface and mass doses.

4 Discussion

Recent research has demonstrated that ENM polydispersity and agglomeration stability and polydispersity can have profound impacts on ENM toxicity in vitro (Liu et al., 2009, Tedja, 2011). Harmonized methods for in vitro nanotoxicity assessments must therefore include ENM dispersion preparation and characterization protocols that ensure fairly monodispersed and stabilized ENM suspensions suitable for in vitro cellular studies. The sonication protocol proposed here includes the important step of identifying the material specific DSEcr, which defines the sonication energy necessary to establish a monodisperse suspension with minimal agglomeration (Fig. 2) that maintains its size distribution over time (Fig. 3). Both the monodispersity and the stability of ENM dispersions over time influence the particle mobility and delivery of particles to cells. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to ensure that the dispersion protocol delivers sonication energy at or above the DSEcr in order to achieve monodisperse ENM suspensions with particle size distributions that remain stable for the duration our toxicological evaluation.

This study shed new light on particle interactions in various commonly used dispersion media for a panel of industry relevant nanosized metal oxide particles. Consistent with the previous reports in the literature, particle-particle interactions were influenced by primary particle properties (primary particle size, surface chemistry), as well as media characteristics (specific conductance, protein content) (Ji et al., 2010, Jiang, 2009, Murdock et al., 2008, Bihari et al., 2008, Zook et al., 2010). For example, a sonication energy (DSEcr) of 161 J/ml was required to achieve a monodisperse solution (PdI = 0.188) of minimal agglomeration size (dH= 123.8 nm) for VENGES SiO2 (dBET=11.9nm) in DI H2O, in which a zeta potential of −22.1 mV was observed. Hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential remained relatively stable when diluted in to RPMI alone (dH= 114.5 nm, ζ = −25.4 mV). However, when dispersed in either RPMI/10%FBS or RPMI/1%BSA, zeta potential was decreased by approximately 50% (ζ = −12.3mV in RPMI/10%FBS, ζ = −14.6 mV in RPMI/1%BSA), consistent with the formation of protein coronae surrounding particles and adding bulk to agglomerates, as described by Lundqvist et al (Lundqvist et al., 2008). Increased bulk and decreased electrostatic repulsion between particles, due to the presence of proteins on the agglomerate surface,, may explain the observed increase in agglomeration size in these media (dH= 123.8nm in DI H2O, dH = 203.97nm in RPMI/10%FBS, dH = 143.8nm in RPMI/1%BSA). In contrast VENGES Fe2O3 (dBET=4.8nm) required a higher DSEcr of 242 J/ml in DI H2O, a media of low specific conductance (σ = 0.0148 mS/cm), to effectively break down agglomerates and achieve a monodisperse suspension. When diluted in RPMI alone, a media of high specific conductance (σ = 11.0 mS/cm), the zeta potential decreased from 27.8mV to −16.7mV. This dramatic change in electrostatic charge may explain the striking increase in agglomeration size observed in RPMI (dH=4333nm). According to the extended DLVO theory (Derjaguin, Landa, Verwey, and Overbeek), the stability of a colloidal suspension depends upon the net balance of all forces acting on the suspended particles: electrostatic, van der Waals, steric, electrosteric, depletion, solvation etc. In suspension, electrostatic repulsion is a major force preventing particle aggregation via the formation of the Electrical Double Layer (Derjaguin, 1941). In media of high specific conductance, the electrical double layer surrounding the particles is compressed, resulting in a decreased zeta potential. This decrease in repulsive electrostatic forces allows van der Waals attractions to dominate and ENM agglomeration to occur. In RPMI/10%FBS and RPMI/1%BSA, the formation of protein coronas around agglomerates and the resulting steric hindrance between particles may explain the relatively smaller agglomerate sizes (225.5nm in RPMI/10%FBS, 937.4nm in RPMI/1%BSA). A similar pattern of particle transformation was observed for CeO2 and TiO2 ENMs, consistent with previously reported transformations of these ENMs in various media (Ji et al., 2010, Sehgal et al., 2005).

Appropriate characterization of ENM suspensions are required for accurate determination of administered doses. Most often, primary particle diameter (dBET) is used for estimating administered dose. However, this approach does not account for the influence of particle interactions and agglomeration in physiological media (Rushton et al., 2010, Wittmaack, 2007). The variable particle agglomeration sizes and resulting administered doses for ENMs in different media formulations presented in Table 4 demonstrate the importance of agglomeration state in calculating dose. From these data it is clear that the media- specific agglomeration state of ENMs in suspension influences the administered number and surface doses (NA and SAA), with implications for the subsequent fate and transport of the ENMs, their delivery to cells, and ultimately their toxicity. Differences between traditionally reported administered doses, based on the dBET, and those based on the media-specific rH values may explain some discrepancies in the literature. Agglomeration and partico-kinetics can also influence particle mobility and the subsequent dose delivered to cells. For each ENM in our panel, the material- and media- specific deposition fraction constant α, was highly variable and dependent upon particle characteristics such as density and agglomeration state (Table 5, Figure 5). Our in vitro cytotoxicity data for VENGES 10Ag/SiO2 (dBET=5.3nm) underscored the importance of utilizing these types of media-particle characterization-based dose metrics when evaluating cytotoxicity. Significant decreases in cell viability were observed following 24 hours of exposure, compared with only 4 hours for all three ENM-media systems (Figure 6, Table 6). Comparisons of various administered and delivered doses demonstrated that particle interactions in liquid media and the subsequent deposition kinetics significantly influence the timing and extent of cytotoxic events observed in vitro. Taken together, our data suggests that delivered doses estimated from properly characterized ENM dispersions may be more physiologically relevant than traditionally reported primary particle size-based administered doses. This physiological relevance, combined with conceptual simplicity of the particle-media specific deposition constant, α, and the ease with which it can be determined, make this approach an attractive option for use in the design of in vitro cellular assays.

In future studies we plan to extend our investigation to deposition fraction constants and delivered dose metrics for additional industrially relevant ENMs. Additional studies are also necessary to confirm the delivery doses estimated here, for which only indirect supportive evidence has been presented to date. It will also be necessary to investigate the kinetics and mechanisms involved in the internalization of particles by cells, including actively phagocytic cells such as macrophages (of which many varieties of primary and cell line macrophages should be examined), as well as other cell types whose interactions with particles may differ substantially from those with macrophages and from each other.

5 Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that particle kinetics and property transformations in physiological fluids have important implications for in vitro dosimetry, and should be central to the design and interpretation of cellular toxicological studies of ENMs. Harmonization of ENM dispersion protocols should include proper reporting of dispersion protocols and delivered sonication energy, which should be sufficient to establish stable monodisperse suspensions. The importance of considering the particle dose actually delivered to cells is also demonstrated, and the fact that this is not typically done may explain some of the discrepancies in the nanotoxicology literature. Furthermore, it is critical that in vitro toxicity protocols employ relevant exposure times derived from robustly characterized ENM- and media-specific particle-kinetics. The importance of particle-kinetics in various physiological media for a panel of industrially relevant nano-sized metal oxides was demonstrated. A simple exponential deposition function was proposed (Equation 8), and a particle- and media-specific constant, α, was obtained for each ENM-media system. This simple empirical function can be used to estimate delivered particle doses at specified times. In future studies, it will also be necessary to investigate the kinetics of particle internalization by cells, and to link this to particle and media specific parameters. Evaluation of various administered, delivered, and internalized dose metrics will help to illuminate the mechanisms by which ENM induce cellular toxicity, and improve the consistency, relevance and validity of in vitro toxicity evaluations.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

Comparison of delivered mass (μg) and surface area (cm2) doses for various ENM dispersed in RPMI at a mass concentration of 50μg/ml following 24 hours of exposure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Georgios Sotiriou (Particle Technology Laboratory, ETH Zurich) for the electron microscopy imaging, BET and XRD analysis of the ENM samples, and Dr Justin Teeguarden (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA, US) for the providing the MATLAB software implementation of the ISDD dose delivery model.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest

The authors declared no personal interests related to this study. This research project was supported by NIEHS grant (ES-0000002) and the Center for Nanotechnology and Nanotoxicology at The Harvard School of Public Health.

References

- BALBUS JM, MAYNARD AD, COLVIN VL, CASTRANOVA V, DASTON GP, DENISON RA, DREHER KL, GOERING PL, GOLDBERG AM, KULINOWSKI KM, MONTEIRO-RIVIERE NA, OBERDORSTER G, OMENN GS, PINKERTON KE, RAMOS KS, REST KM, SASS JB, SILBERGELD EK, WONG BA. Meeting report: hazard assessment for nanoparticles--report from an interdisciplinary workshop. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1654–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIHARI P, VIPPOLA M, SCHULTES S, PRAETNER M, KHANDOGA AG, REICHEL CA, COESTER C, TUOMI T, REHBERG M, KROMBACH F. Optimized dispersion of nanoparticles for biological in vitro and in vivo studies. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAIN J. Biologic responses to nanomaterials depend on exposure, clearance, and material characteristics. Nanotoxicology. 2009;3:7. [Google Scholar]

- CHOI HS, ASHITATE Y, LEE JH, KIM SH, MATSUI A, INSIN N, BAWENDI MG, SEMMLER-BEHNKE M, FRANGIONI JV, TSUDA A. Rapid translocation of nanoparticles from the lung airspaces to the body. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1300–3. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAIGNEAULT M, PRESTON JA, MARRIOTT HM, WHYTE MK, DOCKRELL DH. The identification of markers of macrophage differentiation in PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELOID GM, SULAHIAN TH, IMRICH A, KOBZIK L. Heterogeneity in macrophage phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus strains: high-throughput scanning cytometry-based analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMOKRITOU P, BUCHEL R, MOLINA RM, DELOID GM, BRAIN JD, PRATSINIS SE. Development and characterization of a Versatile Engineered Nanomaterial Generation System (VENGES) suitable for toxicological studies. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22(Suppl 2):107–16. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.499385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERJAGUIN BV. Theory of the stability of strongly charged lyophobic sols and of the adhesion of strongly charged particlces in solutions of electrolytes. Acta Physicochim. 1941;14:30. [Google Scholar]

- ELZEY S. Agglomeration, isolation and dissolution of commercially manufactured silver nanoparticles in aqueous environments. J Nanopart Res. 2009;12:14. [Google Scholar]

- FADEEL B. Better safe than sorry: Understanding the toxicological properties of inorganic nanoparticles manufactured for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;8:9. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER HC, CHAN WC. Nanotoxicity: the growing need for in vivo study. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEORGE S. Use of a High-Throughput Screening Approach Coupled with In Vivo Zebrafish Embryo Screening to Develop Hazard Ranking for Engineered Nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2011;5:13. doi: 10.1021/nn102734s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINDERLITER PM, MINARD KR, ORR G, CHRISLER WB, THRALL BD, POUNDS JG, TEEGUARDEN JG. ISDD: A computational model of particle sedimentation, diffusion and target cell dosimetry for in vitro toxicity studies. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JI Z, JIN X, GEORGE S, XIA T, MENG H, WANG X, SUAREZ E, ZHANG H, HOEK EM, GODWIN H, NEL AE, ZINK JI. Dispersion and stability optimization of TiO2 nanoparticles in cell culture media. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:7309–14. doi: 10.1021/es100417s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG J. Does nanoparticle activity depend upon size and crystal phase. Nanotoxicology. 2008;2:10. doi: 10.1080/17435390701882478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG J. Characterization of size, surface charge, and agglomeration state of nanoparticle dispersions for toxicological studies. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11:13. [Google Scholar]

- JONES CF, GRAINGER DW. In vitro assessments of nanomaterial toxicity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:438–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREWSKI D, ACOSTA D, JR, ANDERSEN M, ANDERSON H, BAILAR JC, 3RD, BOEKELHEIDE K, BRENT R, CHARNLEY G, CHEUNG VG, GREEN S, JR, KELSEY KT, KERKVLIET NI, LI AA, MCCRAY L, MEYER O, PATTERSON RD, PENNIE W, SCALA RA, SOLOMON GM, STEPHENS M, YAGER J, ZEISE L. Toxicity testing in the 21st century: a vision and a strategy. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2010;13:51–138. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2010.483176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAI DY. Toward toxicity testing of nanomaterials in the 21st century: a paradigm for moving forward. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/wnan.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAXEN DPH. A specific conductance method for quality control in water analysis. Water Research. 1977;11:4. [Google Scholar]

- LEE G, WANG Z, SEHGAL R, CHEN CH, KIKUNO K, HAY B, PARK JH. Drosophila caspases involved in developmentally regulated programmed cell death of peptidergic neurons during early metamorphosis. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:34–48. doi: 10.1002/cne.22498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU S, WEI L, HAO L, FANG N, CHANG MW, XU R, YANG Y, CHEN Y. Sharper and faster “nano darts” kill more bacteria: a study of antibacterial activity of individually dispersed pristine single-walled carbon nanotube. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3891–902. doi: 10.1021/nn901252r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDQVIST M, STIGLER J, ELIA G, LYNCH I, CEDERVALL T, DAWSON KA. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14265–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLS NL, DONALDSON K, HADOKE PW, BOON NA, MACNEE W, CASSEE FR, SANDSTROM T, BLOMBERG A, NEWBY DE. Adverse cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURDOCK RC, BRAYDICH-STOLLE L, SCHRAND AM, SCHLAGER JJ, HUSSAIN SM. Characterization of nanomaterial dispersion in solution prior to in vitro exposure using dynamic light scattering technique. Toxicol Sci. 2008;101:239–53. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEL A, XIA T, MADLER L, LI N. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science. 2006;311:622–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OBERDORSTER G. Toxicology of nanoparticles: A histroical perspective. Nanotoxicology. 2007;1:24. [Google Scholar]

- OBERDORSTER G, FERIN J, LEHNERT BE. Correlation between particle size, in vivo particle persistence, and lung injury. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 5):173–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.102-1567252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OBERDORSTER G, OBERDORSTER E, OBERDORSTER J. Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:823–39. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Preliminary Guidance Notes on Sample Preparation and Dosimetry for the Safety Testing of Manufactured Nanomaterials. 2010;58 [Google Scholar]

- RALLO R, FRANCE B, LIU R, NAIR S, GEORGE S, DAMOISEAUX R, GIRALT F, NEL A, BRADLEY K, COHEN Y. Self-Organizing Map Analysis of Toxicity-Related Cell Signaling Pathways for Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Environ Sci Technol. 2011 doi: 10.1021/es103606x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCO MC. Nanotechnology Research Directions for Societal Needs in 2020 2010 [Google Scholar]

- RUSHTON EK, JIANG J, LEONARD SS, EBERLY S, CASTRANOVA V, BISWAS P, ELDER A, HAN X, GELEIN R, FINKELSTEIN J, OBERDORSTER G. Concept of assessing nanoparticle hazards considering nanoparticle dosemetric and chemical/biological response metrics. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:445–61. doi: 10.1080/15287390903489422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEHGAL A, LALATONNE Y, BERRET JF, MORVAN M. Precipitation-redispersion of cerium oxide nanoparticles with poly(acrylic acid): toward stable dispersions. Langmuir. 2005;21:9359–64. doi: 10.1021/la0513757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAW SY, WESTLY EC, PITTET MJ, SUBRAMANIAN A, SCHREIBER SL, WEISSLEDER R. Perturbational profiling of nanomaterial biologic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7387–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802878105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOTIRIOU GA, DIAZ E, LONG MS, GODLESKI J, BRAIN J, PRATSINIS SE, DEMOKRITOU P. A novel platform for pulmonary and cardiovascular toxicological characterization of inhaled engineered nanomaterials. Nanotoxicology. 2011 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.604439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULAHIAN TH, IMRICH A, DELOID G, WINKLER AR, KOBZIK L. Signaling pathways required for macrophage scavenger receptor-mediated phagocytosis: analysis by scanning cytometry. Respir Res. 2008;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAUROZZI J. Protocol for Preparation of Nanoparticle Dispersions from Powdered Material Using Ultrasonic Disruption. CEINT/NIST 2010 [Google Scholar]

- TAUROZZI JS, HACKLEY VA, WIESNER MR. Ultrasonic dispersion of nanoparticles for environmental, health and safety assessment - issues and recommendations. Nanotoxicology. 2010 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.528846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEDJA R. Biological impacts of TiO2 on human lung cell lines A549 and H1299: particle size distribution effects. J Nanopart Res. 2011;13:13. [Google Scholar]

- TEEGUARDEN JG, HINDERLITER PM, ORR G, THRALL BD, POUNDS JG. Particokinetics in vitro: dosimetry considerations for in vitro nanoparticle toxicity assessments. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:300–12. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERMA A, STELLACCI F. Effect of surface properties on nanoparticle-cell interactions. Small. 2010;6:12–21. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIOGO HT, LIM M, BULMUS V, YUN J, AMAL R. Stabilization of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in biological media by fetal bovine serum (FBS) Langmuir. 2011;27:843–50. doi: 10.1021/la104278m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITTMAACK K. In search of the most relevant parameter for quantifying lung inflammatory response to nanoparticle exposur. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOOK JM, MACCUSPIE RI, LOCASCIO LE, HALTER MD, ELLIOTT JT. Stable nanoparticle aggregates/agglomerates of different sizes and the effect of their size on hemolytic cytotoxicity. Nanotoxicology. 2010 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.536615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.