Abstract

Patient: Female, 56

Final Diagnosis: Erdheim-Chester disease

Symptoms: Slurred speech • unsteady gait • walking difficulties

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

The diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease, a rare illness, is difficult and requires increased awareness.

Case Report:

We report the case of a 56-year-old woman who initially presented with a mesenteric panniculitis and 8 years later developed neurological manifestations and bone lesions that led to a diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease.

Conclusions:

The rather characteristic aspect of the bone lesions as well as the presence of foamy cells in involved tissue biopsies should suggest the diagnosis. No therapy is available at present but recent biological data might suggest new approaches for the understanding and therapy of this condition.

MeSH Keywords: Bone Diseases; Erdheim-Chester Disease; Histiocytosis, Non-Langerhans-Cell

Background

Erdheim-Chester disease is a rare illness which can present various unusual clinical aspects. It is a histiocytosis characterized by an infiltration of various tissues and organs by spumous histiocytes, without evidence of malignancy. Many different sites can be involved: bones, retroperitoneum, pleuro-pulmonary sites, skin, and central nervous system can be infiltrated as well. Currently, there is no effective therapy. Our case might contribute to an increased awareness of this disease by stressing the skeletal rather than specific aspects of the condition.

Case Report

This 56-year-old woman was admitted for difficulties with walking and several falls. She had been well until 4 weeks earlier when she noticed a progressively increasing unsteady gait and a slurred speech.

The patient had no significant medical or surgical history except for the diagnosis of a “mesenteric panniculitis” 8 years before. The lesion was not resectable, as shown in Figure 1. An open surgical biopsy was performed and the pathological examination showed histiocytic cell proliferation within a myxoid stroma, with inflammatory cells, myofibroblasts, and a few aggregates of large foamy cells. No specific diagnosis was made. A several-week course of high-dose methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg) was administered (with the putative diagnosis of an inflammatory or granulomatous disease), without any change in the retroperitoneal mass. Because the patient had no morbid symptoms, no further therapy was prescribed.

Figure 1.

Abdominal contrast enhanced computed tomography demonstrating a large infiltrating mesenteric mass (arrows).

The patient was regularly seen at the outpatient clinic until 2002. In 2004, a pericardial effusion was observed incidentally. The work-up demonstrated inflammatory cells in the pericardial fluid but no specific diagnosis could be made. No clinical or radiological progression could be detected. The patient was lost to follow-up in 2005.

The patient was a schoolteacher and had 2 daughters in good health. Her personal family history was unremarkable. She had not been exposed to toxic agents and had not travelled extensively with contacts with animals. She did not smoke, drink alcohol, or take illicit drugs.

The patient was complaining of fatigue, constipation, night sweats, and difficulties with normal standing and walking, as well as of a swelling of the cheekbones. She was noticed by relatives to have a deep non-fluent voice.

At examination, the patient was not disoriented. Her vital signs were normal (blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate) and she was afebrile.

The heart sounds were faint, with no murmur; the lungs were clear. A large mass was palpable in the periumbilical region, with no obvious changes from previous examinations. There was no hepato-splenomegaly and there was no fluid in the abdomen. Neurological examination was suggestive of cerebellar ataxia; a hyperreflexia was observed in the upper and lower right limbs, with a clonus and Babinski sign.

The 2 supraorbital arches were deformed by an underlying hypertrophic bone structure (see Figures 2 and 3); biopsy showed multiple foamy cells suggestive of a xanthoma (Figure 4).

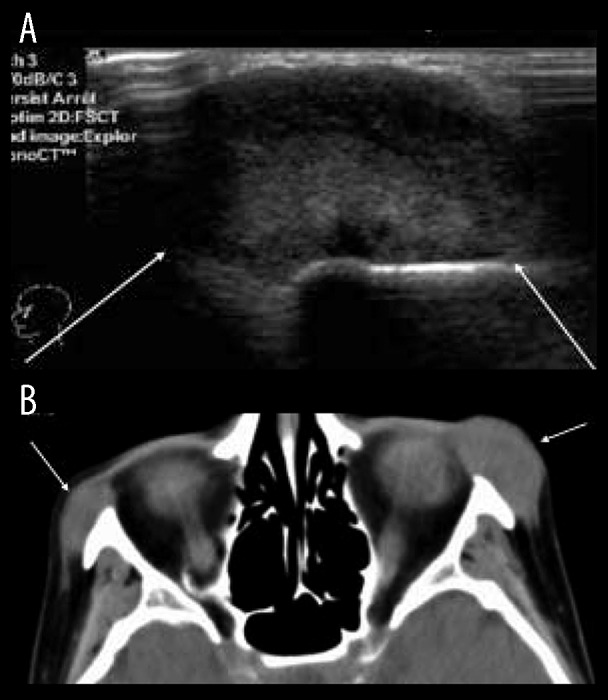

Figure 2.

Prominent zygomatic arches.

Figure 3.

(A) Ultrasound of the cheekbone showing a solid hyperechoic soft tissue mass well delineated [arrows]. (B) Solid homogenous masses appearance on computed tomography. These masses append the zygomatic arches without bony erosion or periosteal reaction.

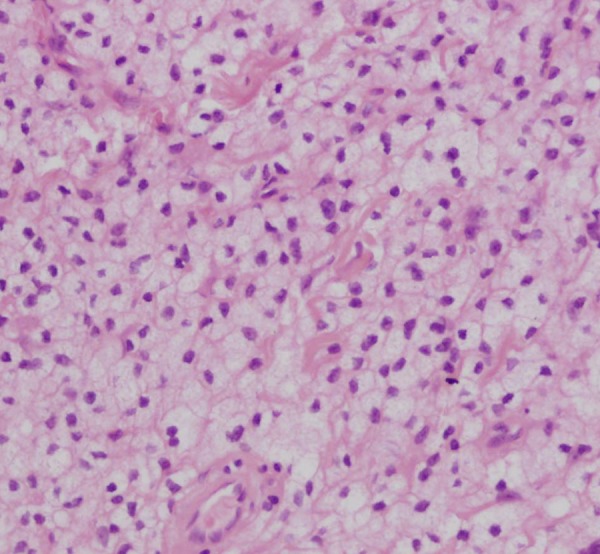

Figure 4.

Histopathology: multiple foamy cells.

Further work-up confirmed a pericardial effusion with inflammatory cells.

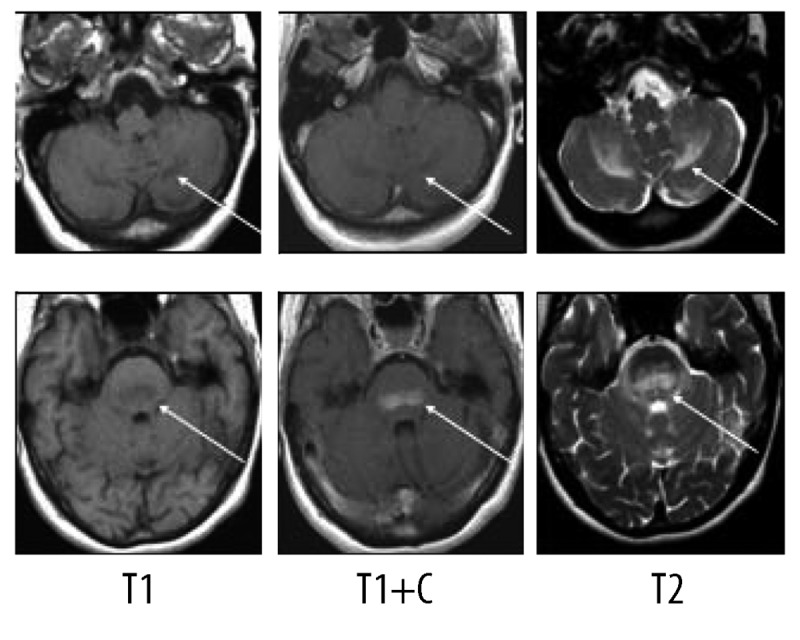

An MRI examination of the brain showed T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense lesions in the pontine region, which were enhanced after gadolinium injection; these lesions were extending into the cerebellar peduncles and the cerebellar hemispheres (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

On MR, presence of lesions in the cerebellar peduncles extending to the cerebellar hemispheres.

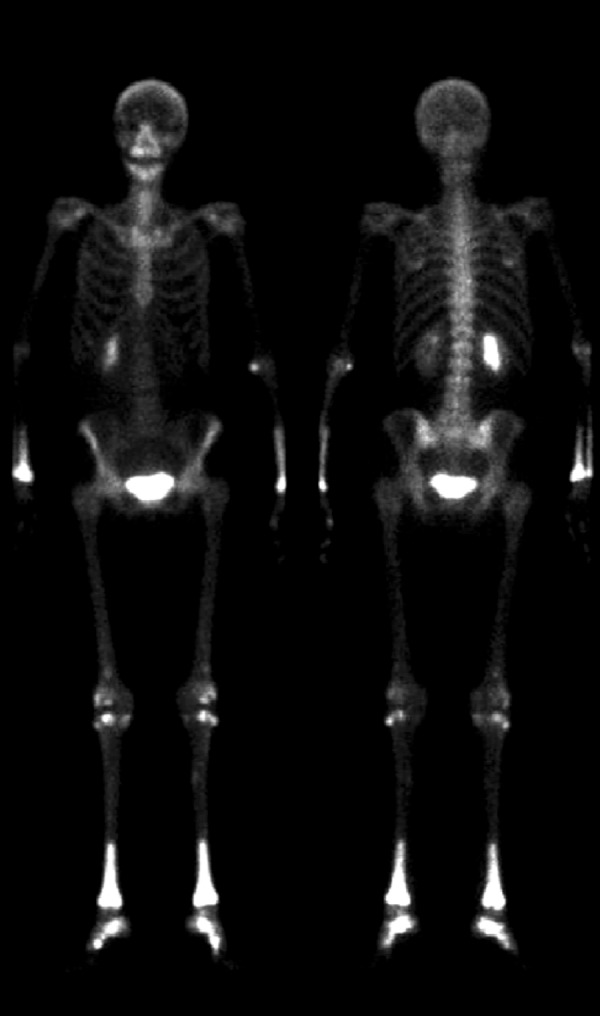

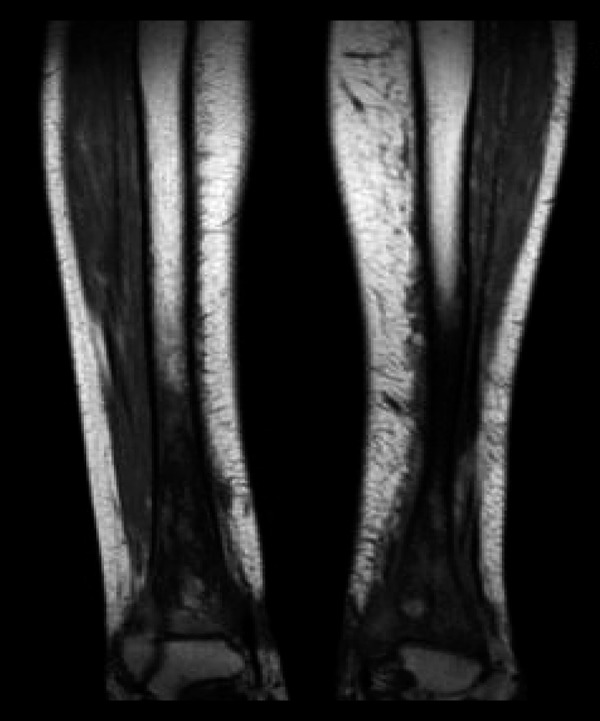

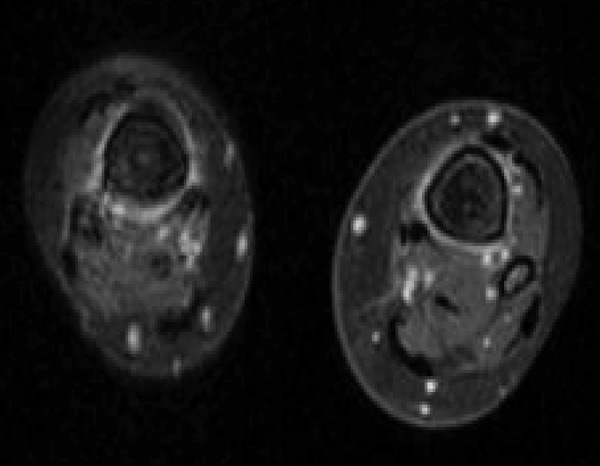

The skeletal workup consisted of a bone scan (increased uptake distal extremities) (Figure 6) and regular X-rays (showing diffuse sclerotic changes of the distal extremities) (Figures 7, 8); these sclerotic lesions were T1 and T2 hypointense signal on MRI (Figure 9), with discrete hyperintense signal on T2 in the peripheral areas and under the periosteum (Figure 10).

Figure 6.

99Tc bone scintgraph with increased uptake of distal long bone extremities.

Figure 7.

Plain radiograph showing diffuse sclerotic changes of the distal extremity of the radius and cubitus.

Figure 8.

Plain radiograph showing diffuse sclerotic changes of the distal extremity of the tibiae.

Figure 9.

Diffuse hypointensity of the signal in the extremity of the tibiae, on MR T1 sequence.

Figure 10.

Peripheral hyperintense signal around cortex and the level of the medullar bony infiltration, on MR T2 sequence.

At this point, the patient received a diagnosis of Erdheim-Chester disease, on the basis of the skeletal manifestations and the results of the bone biopsy.

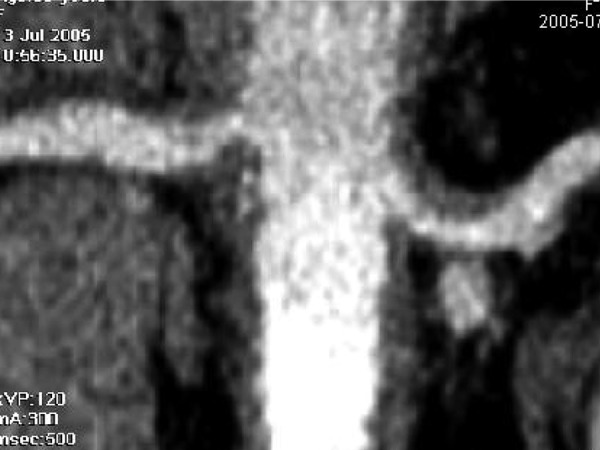

The patient rapidly deteriorated neurologically and developed severe arterial hypertension considered to be related to retroperitoneal involvement of the renal arteries (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Coronal reconstruction of a CT at the level of the renal arteries demonstrating a thickened vascular wall at the origin of these arteries.

The patient died a few weeks after her admission; at post mortem examination, extensive histiocytic infiltration with large foamy cells was confirmed in the bones, the retroperitoneal region, and around the aorta and the renal arteries, as well as in the pericardium.

Discussion

Erdheim-Chester disease is a relatively rare illness, manifested by lesions within the peripheral skeleton. This is the feature that we wish to emphasize in the present case report. It is slightly more frequent in males (sex ratio 1.2–1.5) and is most often diagnosed during the sixth decade of life [1–4].

The bone lesions are bilateral and symmetric and are localized in the distal limb bones, mainly in the lower limbs. The lesions are most often localized at the diaphysis-metaphysis junction with no or little involvement of the epiphysis. Clinically, their manifestation consists of local pain and edema [5–7]. These aspects were present in our patient. Our patient presented with very significant periorbital lesions, which are quite common with this disease [8,9].

Lytic bone lesions have also been described as geodes with clear margins, but are less common. In case of coexisting sclerotic and lytic lesions, there is a possibility that Erdheim-Chester disease and eosinophilic granuloma coexist [10,11].

The technetium-99m bone scan often demonstrates hypercaptation, while in other “histiocytic” disorders this is not as constant [7].

In extra-skeletal localizations of the disease, the retro-peritoneal involvement is by far the most frequent (30–50%); however, retroperitoneal infiltration is most often asymptomatic and is occasionally manifested by lower lumbar pain, problems with urination, and proteinuria with or without renal function impairment [1,3,4].

The involvement of the central nervous is also relatively frequent and causes intracerebral or intramedullary lesions. The clinical manifestations are clearly dependent on the anatomical localization of the lesions. Infiltration of the pituitary stalk may cause diabetes insipidus [3,5,13]. MRI imaging usually shows increased contrast after gadolinium administration, which was not the case in our patient [12–14].

Pulmonary infiltration is less common; it usually consists in a diffuse reticulo-nodular infiltration of both lungs, resulting in progressive dyspnea. This latter symptom may also be caused by myocardial or pericardial infiltration due to the disease, but can also be due to pleural effusions resulting from pleural infiltration by the disease [15]. Other sites of the disease are occasionally seen: skin, liver, spleen, or isolated mesenteric infiltration. Recent reviews confirm the usual presentation of Erdheim-Chester disease as outlined here [16–18].

In our case, the initial presentation of the Erdheim-Chester disease was a retro-peritoneal mass; however, although that kind of presentation is classical, the correct diagnosis had not been made. The patient remained stable in terms of retroperitoneal mass for many years. A pericardial effusion was investigated, but no specific diagnosis was made (inflammatory non-specific cells in the pericardial effusion).

Six years after initial presentation, the patient developed serious neurological symptoms, manifested as cerebellar and pyramidal involvement caused by infiltration of the pons and cerebellum. At the same time, peri-orbital infiltration was noticed and confirmed by histology. Although not very symptomatic, the patient had local pain and edema, and involvement of the distal extremities was radiologically demonstrated. Finally, extensive infiltration of the retroperitoneal space led to a compression of the renal arteries, resulting in severe arterial hypertension.

From the pathological point of view, Erdheim-Chester disease is due to a proliferation of foamy histiocytes causing granulomatous and fibrotic changes in various tissues, mainly the retroperitoneal space and skeleton. This disease can be distinguished from histiocytosis X (Langerhans cells) on the basis of immunochemistry showing the presence of protein S-100, which is characteristic of Langerhans cells [1,2,5].

Erdheim-Chester disease is a multi-system illness with predominantly bone, retroperitoneal, and peri-orbital involvement, which was clearly illustrated in our patient. The course of the disease is highly variable, but long delays between the successive progressions are common, as seen in our case and can vary from months to years (more than 15) [1,4].

The overall prognosis of Erdheim-Chester disease depends on the severity of the extra-skeletal lesions, such as pericardial tamponade, neurological involvement, and retroperitoneal infiltration leading to renal failure or sepsis [1,16,17]. The usual duration of survival varies from a few months (3 months) to many years (10 years).

Conclusions

There is at present no known therapy for Erdheim-Chester disease. Corticosteroids are often used, as in our patient, but there is no evidence for their efficacy. Cytostatic chemotherapy, extensive surgery, and radiation therapy have been used without success [16,17].

Recently, there has been some evidence for a role of the oncogenetic BRAFV600E mutation in this histiocytosis pathogenesis [19,20]. These findings might suggest new avenues for the mechanisms responsible for the disease and potential therapeutic possibilities.

Erdheim-Chester disease is a systemic “histiocytosis” caused by non-Langerhans cells and typically foamy histiocytes, mainly involving bones and the retroperitoneal space. Although the course may be protracted, the overall prognosis is relatively poor.

References:

- 1.Veyssier-Belot C, Cacoub P, Caparros-Lefebvre D, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59 cases. Medecine. 1996;75(3):157–69. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez C, Diard F, Chateil JF, Moinard M. Imagerie de la maladie d’Erdheim-Chester. J Radiol. 1996;77:1213–21. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cattin F, Runge M, Nagy N, et al. [Case #5. Erdheim-Chester disease] J Radiol. 2005;86:527–30. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(05)81404-0. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenn W, Stäbler A, Zachoval R, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: a case report and literature overview. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:153–58. doi: 10.1007/s003300050647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breuil V, Brocq O, Pellegrino C, et al. Erdheim-Chester Disease: typical radiological bone features for a rare xanthogranulomatosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;66:199–200. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans S, Williams F. Case report: Erdheim-Chester disease: Polyostotic sclerosing histiocytosis. Clin Radiol. 1986;37:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(86)80184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray D, Marshall M, England E, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:481–84. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozas Reyes P, Senaris Gonzales A, Gonzales Rodriguez CM. Orbit xanthogranulomatosis. Erdheim-Chester disease. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2004;79:515–18. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912004001000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosier RN, Rosenberg AE. Case 9–2000 – A 41-year-old man with multiple bony lesions and adjacent soft-tissue masses. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12):875–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waite RJ, Doherty PW, Liepmann M, Woda B. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with the radiographic findings of Erdheim-Chester disease. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:869–71. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.4.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brower AC, Worsham GF, Dudley AH. Erdheim-Chester disease: a distinct lipoidosis or part of the spectrum of histiocytosis? Radiology. 1984;151(1):35–38. doi: 10.1148/radiology.151.1.6608118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez R. Erdheim-Chester disease: MR of intraaxial and extraaxial brain stem lesions. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1787–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weidauer S, von Stuckrad-Barre S, Dettman E, et al. Cerebral Erdheim-Chester disease: case report and review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:241–45. doi: 10.1007/s00234-003-0950-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tien RD, Brasch RC, Jackson DE, Dillon WP. Cerebral Erdheim-Chester disease: persistent enhancement with GD-DTPA on MR images. Radiology. 1989;172:791–92. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.3.2772189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dion E, Graef C, Haroche J, et al. Imaging of thoracoabdominal involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1253–60. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdelfattah AM, Arnaout K, Tabbara IA. Erdheim-Chester disease: A comprehensive review. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(7):3257–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazor RD, Manevich-Mazor M, Shoenfeld Y. Erdheim-Chester disease: a comprehensive review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:137. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Versini M, Jeandel PY, Fuzibet JG, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: radiological findings. Presse Med. 2010;39(11):e233–37. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavalli G, Biavasco R, Borgiani B, Dagna L. Oncogene-induced senescence as a new mechanism of disease: the paradigm of Erdheim-Chester disease. Front Immunol. 2014;5:281. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hervier B, Haroche J, Arnaud L. French Histiocytoses Study Group. Association of both Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease linked to the BRAFV600E mutation: a multicenter study of 23 cases. Blood. 2014;124(7):1119–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-543793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]