Abstract

Studies on children of immigrants have generally ignored distinct developmental trajectories during adolescence and their role in the transition to adulthood. This study identifies distinct trajectories in cognitive, socio-behavioral, and psychological domains and estimates their consequences for young-adult. Drawing data from a nationally representative sample of 10,795 adolescents aged 13-17 who were followed up to ages 25-32, we use growth mixture modeling to test advantages for children of immigrants. The analysis shows a 1.5 generation advantage in academic achievement and school engagement, as well as a weaker second-generation advantage in academic achievement, but no disadvantage in depression for children of immigrants. In addition, we found that these results hold for children of Hispanic origin. Theoretical and policy implications are discussed.

Keywords: distinct trajectories, transition to adulthood, children of immigrants, growth mixture modeling

As children of immigrants have come of age in large numbers, researchers have paid increasing attention to their adolescent development (e.g., Crosnoe, 2005; Georgiades, Boyle & Duku, 2007) and young-adult outcomes (e.g., Kasinitz et al., 2008; Hao & Pong, 2008). An immigrant paradox describes an advantage of children of immigrants (born to at least one immigrant parent) over children of natives (born to both native-born parents) in education, health, and behavioral outcomes despite their non-white and low-socioeconomic status (SES) background (Acevedo-Garcia, Pan, Jun, Osypuk, & Emmons, 2005; Georgiades, Boyle & Duku, 2007; Sampson, Morenoff, & Raudenbush, 2005). No consensus on the immigrant paradox has been reached, however. The transition to adulthood via trajectories of multi-domain adolescent development offers a unique opportunity to assess whether children of immigrants are advantaged. The transition may differ between children of immigrants and children of natives and also, among children of immigrants—between the foreign born (1.5 generation) and the native born (second generation). In this paper, we examine whether children of immigrants have an advantage in distinct trajectories of cognitive, socio-behavioral, and psychological domains and reaffirm this advantage by examining the consequences of these trajectories for young-adult educational attainment and psychological well-being.

To achieve this goal, we move adolescent development research forward along three fronts. Recent studies have conceptualized adolescent development as a process rather than a single-point outcome, but they typically have assumed a continuous distribution of trajectories and failed to consider the possibility of distinct subgroups, each with a unique trajectory distribution (McLeod & Fettes, 2007; Stoolmiller, Kim, & Capaldi, 2004). In this paper, we develop a rationale for using distinct trajectories in academic achievement, school engagement, and depression and identify the trajectories using growth mixture modeling (GMM). Second, the large body of literature on transition to adulthood has focused on a single developmental domain. Using the life course framework, we consider distinct trajectories in multiple domains. Third, we examine the consequences of distinct trajectories of multiple domains for young-adult outcomes. With these advancements, we are able to better answer our central research question of whether children of immigrants are advantaged in the transition to adulthood.

Background

Children of Immigrants

This study examines the transition to adulthood of immigrant-parentage children in comparison with native-parentage children. Several previous research studies have shown that children of immigrants do not have a uniform advantage across all educational outcomes or all immigrant groups. Kao (2004), for example, found that when taking SES and other family variables into account, children of immigrants outperform children of natives in virtually all academic subjects except for reading. Hao and Bonstead-Bruns (1998) showed that children of Asian immigrants have higher GPAs and do better in math, whereas children of Mexican immigrants have lower GPAs and do worse in math and reading than do third-generation whites. Glicks and White (2003) found that only native-born children of Mexican immigrants in the 10th grade have an advantage in reading over their native-parentage counterparts. Findings on postsecondary education, too, have suggested that the advantages for children of immigrants are not uniform for all immigrant groups. Hao and Ma (forthcoming), for example, found that only non-Mexicans among children of low-SES Hispanic immigrants fare better than their third-generation counterparts, and children of Asian immigrants have higher rates in college attendance and Bachelor’s degree attainment than third-generation whites and blacks.

With regards to behavioral problems, past research has indicated that immigrant youth fare better than their native counterparts (Harker, 2001; Harris, 1999), engaging in fewer delinquent and violent acts and being less likely to use legal and illegal substances (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2005; Georgiades et al., 2006; Sampson et al., 2005). Children of recent immigrant families have lower levels of behavioral problems than children of native families despite greater socioeconomic disadvantages in the family and neighborhood for immigrant children (Georgiades et al., 2007). Some studies, however, have suggested heterogeneity in behavioral problems within immigrant children groups. Crosnoe (2005), for example, found significantly diverse Hispanic students, with some highly engaged and achieving in schools while many others not so, and the author identified distinct types of student profiles on the combination of school engagement and academic achievement.

The mental health literature has shown mixed results on the differences between children of immigrants and children of natives. According to a review (Stevens & Vollebergh, 2008), foreign-born children suffer greater psychological distress than native-born children for such reasons as abrupt family and peer separations, dissonant acculturation between parents and children, and discrimination and prejudice in the host society. In contrast, more recent studies have found foreign-born youths to fare better in psychological well-being than native-born youths (Harker, 2001) but with considerable within-group heterogeneity (Driscoll, Russell, & Crockett, 2008). Of the few studies that have examined developmental trajectories of mental health, Brown and colleagues (2007) showed that although Asian and Hispanic youths exhibit higher initial level of depressive symptoms, immigrant status itself does not affect adolescent depression trajectories.

Multiple Developmental Domains

Adolescent developmental domains have been conceptualized as interrelated (Elder, 1998; Hair, Moore, Hunter, & Kaye, 2001). Research has shown that childhood emotional and behavioral problems reduce the probability of graduating from high school and attending college (Ensminger & Slusarcick, 1992; Entwisle, Alexander, & Olson, 2005; McLeod & Fettes, 2007; Vitaro, Brendgen, Larose, & Tremblay, 2005; Wagner, 1995). A decline in school engagement in early adolescence lowers educational achievement (Anderman, Maehr, & Midgley, 1999). Compared to disengaged counterparts, students who are motivated to do well are more likely to try hard and perform well academically relative to their abilities and are less likely to drop out (McNeeley, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002). In addition, school behavior problems and inconsistent school attendance are signals of mental health problems (Roderick et al., 1997), while increased depression is associated with school disengagement (Eggert, Thompson, Randell, & Pike, 2002).

Conceptual Issues

Two sets of conceptual issues arise in this study. One involves the sources of an advantage in the transition to adulthood for children of immigrants. The other concerns the rationale behind distinct trajectories in adolescent development. We discuss the two sets of issues in turn.

Why Might Children of Immigrants Have An Advantage?

We would expect a group of individuals to be advantaged in transitioning to adulthood if the group is more likely to follow normatively better trajectories during adolescence and if these trajectories lead to better young-adult outcomes. One such source of advantage for immigrant children is the self-selection of immigrant parents. The costs of migration and the uncertainty of future adaptation in the host society are circumstances that lead to the selection of adult immigrants with certain unobserved traits, such as ambition, motivation, and a desire for better life chances for their offspring (Jasso & Rosenzweig, 1990; Massey et al., 1993). Thus adult immigrants are differentially self-selected, distinguishing themselves from the native born with a stronger drive for upward mobility. Children of immigrants (the 1.5 and second generations) are distinguished from children of natives (the third generation) by their parents’ foreign birthplace and self-selection into voluntary migration.

Researchers typically have conceptualized the influence of immigrant parents’ selectivity on children as an advantage, but the mechanism by which the advantage arises is less clear. Putting immigrants’ self-selection in the context of their children’s education, Kao and Tienda (1995) proposed that immigrant parents are optimistic about their offspring’s educational and socioeconomic prospects, which make their children try harder to achieve academically. It is unclear, though, as to how immigrant parents’ optimism leads their children to adopt behaviors and attitudes in support of academic achievement. Although immigrant optimism is rooted in immigrant parents, Kazinitz et al. (2008) emphasized the agency of immigrant children. They posited that the position of between-ness of the home and host worlds enables children of immigrants to draw the best from each side and develop creative strategies to increase their probability of success. Yet, why children of immigrants are oriented to take advantage of the better of the two cultures is unclear. In other words, what is the source of the agency conducive to academic success? Hao and Bonstead-Bruns (1998) proposed that certain types of parent-child interaction enable the transmission of parental expectation, which leads parents and their children to agree on educational expectations. Children internalize these expectations and consequently work hard to succeed in school. In contrast, expectation disagreement leads to low achievement. Previous studies have shown that immigrant youths, Asian youths in particular, feel obligated to their parents for what they have done for them and believe that it is their family responsibility to do well in school (Fuligni, 1997; Sue & Okazaki, 1990).

Segmented assimilation theory addresses the sources of both advantage and disadvantage for children of immigrants (Portes & Zhou, 1993) and brings together America’s race structure and immigrant incorporation to account for the divergent assimilation patterns of immigrants’ offspring. Hostile or indifferent government policy, prejudiced social reception, and weak co-ethnic communities combine to create vulnerability to downward assimilation, defined as acculturation into the underclass. Being nonwhite and living in central cities place children of immigrants in close contact with marginalized racial-minority peers. With disappearing manufacturing jobs and a loss of hope for moving up the socioeconomic ladder, these children increasingly identify themselves with a racial minority and an adversarial subculture that devalues school engagement and academic achievement. Yet, strong co-ethnic immigrant communities can provide resources to confront vulnerability to downward assimilation. Co-ethnic communities can be strong if residents are heterogeneous in SES and if community organizations are effective in preserving and maintaining beneficial home-country norms and values (Zhou, 2009; Waters et al., 2010). Through community private schools, supplemental educational organizations, and co-ethnic networks that uphold beneficial home-country values, strong co-ethnic communities steer immigrants’ children away from adopting local subcultural values, enforce the premium of education, and reward hard work in school and high academic achievement. Taken together, segmented assimilation theory suggests that three assimilation patterns are possible: upward, selective, and downward. Those children who follow the upward and selective assimilation paths command an advantage, while those who fall into the downward assimilation path face a disadvantage in transitioning to adulthood.

We draw three implications from segmented assimilation theory. First, this theory suggests that assimilation patterns are foremost determined by parental race and class positions (also see Jencks & Philips, 1998). Our testing of the advantage for children of immigrants should hold parental race and class constant. Second, 1.5-generation children are more likely to form a national origin identity and be influenced by co-ethnic immigrant communities than second-generation children (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). The benefit of living in co-ethnic immigrant communities and having a national origin identity should be manifested in the socio-behavioral domain, such as school engagement, and the cognitive domain, such as academic achievement. At the same time, by virtue of being born in the United States, second-generation children are better acculturated with the host language, mainstream values, styles, and etiquettes than 1.5-generation children. Together with the greater parent-child agreed-upon expectations and child agency, second-generation children should exhibit an advantage in academic outcomes. Third, the degree to which children of immigrants are advantaged may depend upon their race-ethnicity, such that racial-ethnic groups that are subject to prejudice are less advantaged.

While 1.5- and second-generation children may have differential advantages in school engagement and academic achievement, the theoretical reasons do not extend to the domain of mental health, and the unique experiences of 1.5- and second-generation children may actually place them at greater risk than third-generation children. Since members of immigrant families often arrive in the United States separately, in a staggered manner, 1.5-generation children may experience stress from parent-child separation, conflict with host value systems, shock from host racial discrimination, up-rooting from home-country peers, and barriers resulting from a new language (Brindis, Wolfe, McCarter, Ball, & Starbuck-Morales, 1995; Schapiro, 2002). In addition, immigrant families are exposed to unique economic hardships, such as overcrowded housing and low-SES that native-born children are less likely to experience (Hernandez, 2004). Finally, immigrant parents’ feelings of economic pressure may heighten emotional distress, which is likely to affect children’s mental health (Conger & Donnellan, 2007).

In sum, existing theories suggest that the intergenerational transmission of ambitious expectations, the agency of children in schooling, and resources from immigrant families and co-ethnic immigrant communities may create an advantage for children of immigrants in the socio-behavioral and cognitive domains. These sources do not necessarily translate into an advantage in the psychological health domain, however. Instead, family separation and economic hardship, which is common for 1.5-generation children, and prejudice, which is common for non-white children, may generate greater stress for children of immigrants, especially those in the 1.5-generation.

Rationale for Distinct Trajectory Classes

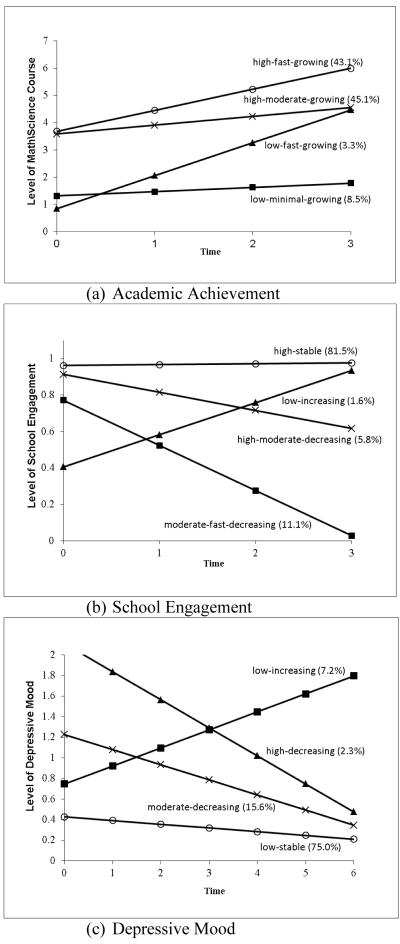

In considering individual trajectories in a developmental domain, we suspect that the conventional assumption of population homogeneity is inappropriate. Research and practice strongly suggest that distinct trajectories exist. For academic achievement, the simplest division is high achievers (good students) and low achievers (poor students). When observing academic achievement as a continuous process over four years (starting from the 9th grade), the distinction can be more nuanced. We can separate out the patterns of academic achievement from the fast-growing type to the moderate-growing type, as well as identify the turn-around type that starts off low but quickly improves. Thus, a priori we propose four latent classes of academic-achievement trajectories. The high-fast-growing includes students who are well-prepared at the start and continue to accumulate achievement quickly because of favorable individual, school, family, and neighborhood conditions. These students are likely to have high motivation to learn, study under high academic pressure, be surrounded by motivated peers, have a high level of parental education, and live with both parents. The high-moderate-growing includes those who are well-prepared initially but may run into weaker conditions that hinder fast achievement growth. The low-fast-growing is tracked by students who are poorly prepared but manage to improve, either because the learning context improves or because individuals become more capable of overcoming their obstacles. Finally the low-minimal-growing characterizes the path for students who are in a bleak situation of poor preparation, low motivation, modest effort, and a poor learning environment.

Although correlated, school engagement does not necessarily entirely overlap with academic achievement. At entry into high school, most students are motivated to continue schooling and reasonably engaged in school learning. As time goes by, low academic pressure, low teacher interest, negative peer pressure, high neighborhood delinquency, as well as low achievement and health problems can lower students’ attachment to school. As with academic achievement, some students may turn around from being lost in a new environment to being fully engaged in school. Here, we categorize students who are held back or dropping out of school as being disengaged. We thus propose four latent classes of school engagement trajectories: high-stable, high-moderate-decreasing, low-increasing, and moderate-fast-decreasing.

A growing literature has provided evidence that there are indeed distinct trajectory classes for mental health, but that they often vary by age range and gender. McLeod and Fettes (2007) studied children of a national sample of women and identified four distinct classes of internalizing problem trajectories over the ages from 6-8 to 16-18: childhood high, childhood moderate, adolescent high, and stably low. In another study, Stoolmiller, Kim, and Capaldi (2003) identified four distinct trajectories of depressive symptoms based on a community sample of Oregon youth: chronic high, high-to-decreasing, moderate-to-decreasing, and stably low. Drawing from these findings, we expect four latent classes of depression trajectories: low-stable, moderate-decreasing, high-decreasing, and low-increasing.

Hypotheses

Immigrant optimism, cultural between-ness, intergenerational transmission of expectation, and segmented assimilation suggest that children of different generation statuses may have different developmental experiences, holding demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual conditions constant. An advantage in transition to adulthood implies a greater probability of belonging to the normatively better classes of developmental trajectories that lead to better young-adult outcomes, provided that distinct trajectory classes exist.

Academic achievement results from the interaction between individual agency and learning environment. Based on immigrant optimism and cultural between-ness, we expect that children of immigrants are less likely to fall in the worst type (low-minimal-growing) of academic trajectory compared to third-generation children. In addition, we expect that 1.5-generation children are more likely to enter the low-fast-growing academic trajectory (H1a) and that second-generation children tend to enter the best type (high-fast-growing) (H1b). The 1.5 generation faces being poorly prepared with the foundational knowledge associated with different curriculum structures and instructional languages in the home country and limited English proficiency.

Given that school engagement reflects children’s motivation and effort to learn, we expect that children of immigrants are less likely to become disengaged over time (moderate-fast-decreasing) than children of natives (H2). The likelihood of high-stable engagement is expected to be higher for the 1.5 generation than for the second generation, given the stronger influence of national origin identity and the co-ethnic immigrant community against downward assimilation on 1.5-generation children (H2a).

If children of immigrants are more prone to depression, their transition to adulthood will be troublesome despite their advantage in academic achievement and school engagement. We expect that adaptation stressors subject children of immigrants to depressive-prone trajectories rather than the low-stable type (H3). Having had initially traumatic immigration experiences yet stronger family and community support may place 1.5-generation children in the high-fast-decreasing trajectory (H3a), whereas heightened parent-child conflict resulting from dissonant acculturation may place second-generation children in the low-increasing category (H3b).

Segmented assimilation theory also points to the importance of race-ethnicity in differential downward assimilation. Children of immigrants are hypothesized to have an advantage after race is held constant. Nevertheless, the magnitude of advantage may differ across racial-ethnic groups. Given the stronger co-ethnic communities of Asian immigrants than those of Hispanics, we hypothesize that the 1.5- and second-generation advantage is weaker for children of Hispanic immigrants than for children of Asian immigrants (H4).

Data and Methods

Data and Sample

Data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) and the Adolescent Health and Academic Achievement (AHAA) have two salient strengths: They feature a national sample of all generations and uninterrupted 4-year academic-achievement and school-engagement trajectories. These characteristics are typically absent from other relevant surveys, such as the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study. At the same time, Add Health and AHAA have limitations common to national surveys, such as a lack of in-depth community contexts, small subsamples of certain national-origin groups, and the absence of detailed immigrant characteristics, such as refugee status. For the purpose of this study seeking to identify national patterns for children of immigrants in comparison with children of natives, the strengths outweigh the limitations. The four waves of Add Health data, which were collected over 13 years in 1994-1995, 1996, 2001-2002, and 2007-2008, provide longitudinal data for a large nationally representative sample of adolescents in grades 7-12 in the first wave. In the AHAA study, approximately 91% of Wave III respondents consented to allow the collection of their high-school transcripts. A total of 12,217 Add Health respondents have valid transcript data. Starting from this AHHA sample, we selected our analytic sample according to the following criteria: born in 1976-1982, aged 13-17 at 9th grade, and have valid data on race-ethnicity, generation status, parental education, and high-school sector. The resulting analytic sample included 10,795 individuals.

Measurement

To construct measures suitable for adolescents with diverse racial and immigrant backgrounds, we used variables from AHAA to construct objective and uninterrupted profiles of academic progress. We used math and science sequential courses rather than culturally sensitive standardized tests. The math sequence from low to high includes basic and remedial math, general and applied math, pre-algebra, algebra I, geometry, algebra II, advanced math, pre-calculus, and calculus, and the science sequence from low to high is basic and remedial science, general and earth science, biology, chemistry, advanced science, and physics. We simplified the 9-level math sequence to 7 levels, given that algebra I and geometry, as well as advanced math and pre-calculus, are often taken out of sequence. We also simplified the 6-level science sequence to 5 levels, combining biology and chemistry. We then normalized the science sequence according to the math sequence to levels 1-7. Utilizing the sequential nature of math and science courses, we measured academic achievement by computing the weighted mean of the highest sequential math and science courses passed at each year of a 4-year period starting from the 9th grade. If students took courses out of sequence, we carried the previous higher level to the current years. Finally, given that more time is devoted to math than science in the curriculum and that science courses are normalized according to math courses, we assign three fourth weights to math courses and one fourth weight to science courses. Only math and science courses with earned credits were counted. The weighted sum of math and science sequence level is our measure of academic achievement, ranging from 0 to 7. A value of 0 was assigned to dropouts from the 9th grade or students who failed all math and science courses. Held-back students and high-school dropouts remained in the sample, and their latest math and science level was carried forward to the end of the 4-year period. This variable is well suited for non-decreasing academic growth.

To construct the school-engagement variable, we used the proportion of all courses that each individual passed in an academic year, assuming that if students are engaged in learning, they should pass every high-school course. The value of 0 indicates the complete disengagement of high-school dropouts. This measure better captures school engagement than self-reported hours on homework, which could be contaminated by students’ levels of subject knowledge.

The measure of mental health problems was taken from the first three waves of Add Health in 1994-1995, 1996, and 2001-2002. The depression trajectory covered different age ranges: 14-21 for 5.1% of the sample, 15-22 for 17.7%, and so on, until 18-25 for 8.1%. About 3% of the sample that was born earlier, attended 9th grade at a younger age, and did not pursue college education had finished their schooling before the start of depression was measured. Given this small proportion, the potential complexity of time ordering of trajectories in the three domains may be small. Out of the total sample, about 45% had their academic achievement and school-engagement trajectories completely nested in the depression trajectory, and about 52% had at least one year overlapped with the depression trajectory.

We constructed a culturally equivalent depression scale (Perreira et al., 2005) using five items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. These five 4-point (0-3) scale items tap depressive mood, asking whether in the past seven days the respondent (1) could not shake off blues, (2) felt depressed, (3) did not feel happy, (4) did not enjoy life, and (5) felt sad. Aligning the signs and taking the average of the item scores yielded a depression scale with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 3 for each wave. The reliability (indicated by Cronbach alpha) ranged from 0.79-0.82.

Young adult outcomes were measured in Wave IV in 2007-2008, when our sample individuals were aged 25-32, 8-13 years after the last measure of the academic achievement and school-engagement trajectories and 6 years after the last measure of the depression trajectory. Educational attainment was measured with two variables: years of schooling and a 7-category ordinal variable for the levels of the most recent degree (no degree, GED, high-school diploma, AA and vocational degree, Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree or post-baccalaureate certificate, and advanced degree). General psychological well-being was captured by a scale based on five items (not feeling socially isolated, able to control things, confident in handling personal problems, things are going on the right way, and do not feel difficulties overwhelming), with a reliability of 0.74. Wave IV data were available for 9,475 sample individuals. To handle the attritted 1,372 individuals, we used their Wave III information to measure well-being and created an indicator for this attrition status.

The key explanatory variable is generation status. The 1.5 generation includes foreign-born children of immigrants. These children arrived in the United States as minors (as opposed to adults), with three quarters having arrived by age 12. To preserve high testing power, we refrained from further dividing foreign-born children into more refined generation statuses. The second generation includes native-born children of one or both foreign-born parents. The third generation includes all other children who were native-born and whose parents were native-born. Individual-level control variables are race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian), gender, and the age at the 9th grade for the trajectory analysis. To measure family context, we used the highest parental education (years of schooling) and family structure (two-parent family vs. otherwise). To measure school context, we used school sector (public vs. private), average attendance rate, and average classroom size. Although state and district educational policy environments constitute broader contexts, we did not include geocode variables because such inclusion would destabilize the estimation of the model, which is already heavy with a large number of parameters to be estimated (discussed below). Descriptive statistics of all variables used in the analysis for the total sample and by generation status can be found in the Appendix Table.

Analytic Strategies

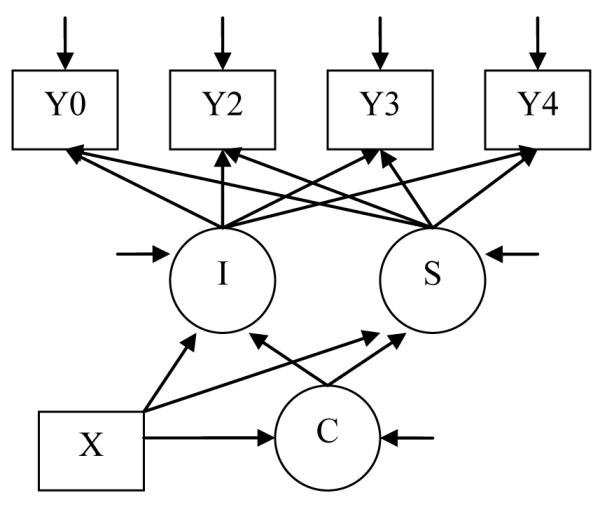

Our latent trajectory class analysis of repeated outcomes in developmental domains applied growth mixture modeling (GMM). The GMM relaxes the conventional assumption of a single distribution of trajectories and allows individual trajectories to follow a mixture of a finite number of distributions (latent classes) (Muthen, 2004; Muthen & Shedden, 1999). Figure 1 shows the diagram of the GMM application for our study. The probability for an individual to fall into a specific latent class, C, is influenced by the set of covariates, X. Within each latent class, repeated observations of a developmental outcome at multiple time points (Y0, Y1, Y2, and Y3 for academic achievement and school engagement and Y0, Y1, and Y6 for depression) form individual trajectories characterized by individual growth factors (intercepts I and linear slopes S), which are also influenced by X. Growth factors differ across the latent classes, characterizing distinct trajectories. Our model includes a large number of free parameters and our data, albeit large in sample size, are still not sufficiently large enough to identify all free parameters. As with previous research on latent trajectory classes, we restricted certain parameters to be equal across latent classes, including the variance of person-time-level residuals, the variance of random intercept residuals, and covariate coefficients for growth factors. We also restricted the variance of slope residuals to be zero. For more details on the GMM application used in this study, see the technical appendix A Growth Mixture Modeling Application at the first author’s website: http://www.ams.jhu.edu/~hao/CD/Appendix_GMM.pdf.

Figure 1.

A GMM Application.

Note: Y’s are continuous measures of developmental outcomes at different time points, I the intercepts and S the slopes of trajectories, C la tent classes of trajectories, and X a vector of covariates.

We analyzed individual trajectories in each domain using the GMM procedure in Mplus 6.1. Because the model is a mixture of distinct distributions of trajectories, we used 500-1,000 random starts to approximate the global maximum using repeated local maxima. Three sets of incremental models with respect to the number of latent classes were estimated. We sequentially increased the number of latent classes from 2 to 5. Both statistical and substantive criteria were used to select an optimal, meaningful, and parsimonious model. The statistical criteria include (a) the model converged without any reported optimization problems; (b) information criteria such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are the lowest; (c) the Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) adjusted likelihood ratio test against the one-less class model is highly significant; and (d) the reliability of the classification indicated by the average probability for the most likely latent class membership is high. Substantively, the class-specific mean trajectories should differ significantly from one another by both initial-state and slope or both slope and end-state that provide substantive and unique information.

The advantage for children of immigrants needs to be reaffirmed through examining whether normatively better trajectory classes lead to better young-adult outcomes. Based on the interdependence of developmental domains, we estimated each young-adult outcome as influenced jointly by the identified distinct trajectories of the three developmental domains.

Results

Distinct Trajectory Classes in Developmental Domains

We checked our model fit statistics against our model-selection criteria. The AIC and BIC declined as the number of classes increased. The 4-class model for each domain met statistical criteria, including the LMR likelihood ratio test and the reliability of classification (a high average probability for each latent class). The 5-class model for academic achievement yielded two parallel trajectories, violating our substantive criteria. The 5-class model for school engagement and depression met neither the statistical nor the substantive criteria. Thus the 4-class model for each domain was chosen as the best model.

Figure 2 draws the mean trajectory of each latent class in the three developmental domains, and Table 2 provides the exact estimated mean intercept and slope for each class. Looking from the top down the academic achievement graph, we see four distinct mean trajectories. Although two trajectories at the top start high, high-fast-growing and high-moderate-growing diverge over time because of a slope difference. These two classes account for 88% of all children. The other two classes are much smaller and of an opposite direction to the first two types: Low-fast-growing turns around from low achievement to high achievement, whereas low-minimal-growing starts low and is stagnant. In the school-engagement graph, the mean trajectories are characterized by high-stable (81.5%), high-moderate-decreasing (5.8%), low-increasing (1.6%), and moderate-fast-decreasing (11.1%). Looking from the bottom up the depression graph, we see four distinct trajectories: low-stable (75%), moderate-decreasing (15.6%), high-decreasing (2.3%), and low-increasing (7.2%). These four distinct trajectories are consistent with those found in McLeod and Fettes (2007), although the percentage distribution of ours differs, probably because of different age groups. The estimates in Table 2 show how the mean intercepts and slopes differ across the distinct trajectories.

Figure 2.

Distinct trajectories in academic achievement, school engagement, and depression during adolescence.

Table 2.

Estimated Growth Factors for Latent Trajectory Classes: Add Health and AHAA

| Covariate | Academic Achievement | School Engagement | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best | high-fast-growing | high-stable | low-stable |

| Intercept | 3.682 ** | 0.962 ** | 0.428 ** |

| Slope | 0.772 ** | 0.005 ** | −0.036 ** |

| Proportion of sample | 0.431 | 0.815 | 0.750 |

| Second best | high-moderate-growing | high-moderate-decreasing | moderate-decreasing |

| Intercept | 3.583 ** | 0.914 ** | 1.228 ** |

| Slope | 0.322 ** | −0.099 ** | −0.147 ** |

| Proportion of sample | 0.451 | 0.058 | 0.156 |

| Third best | low-fast-growing | low-increasing | high-decreasing |

| Intercept | 0.844 ** | 0.406 ** | 2.108 ** |

| Slope | 1.209 ** | 0.176 ** | −0.272 ** |

| Proportion of sample | 0.033 | 0.016 | 0.023 |

| Worst | low-minimal-growing | moderate-fast-decreasing | low-increasing |

| Intercept | 1.312 ** | 0.772 ** | 0.747 ** |

| Slope | 0.155 ** | −0.248 ** | 0.175 ** |

| Proportion of sample | 0.085 | 0.111 | 0.072 |

p < .05

p < .01

The trajectory classes were expected to be associated with covariates, including individual characteristics and family and school contexts. The bivariate relationships between background variables and trajectory classes in Table 3 show which individual characteristics and family-school contexts were more likely to place an individual in a specific trajectory class. Column 1 provides the sample mean as a benchmark. The trajectory classes are ordered from the normatively best to the normatively worst. Regarding academic achievement, more second-generation children belonged to the best class (high-fast-growing), and more 1.5-generation children were classified in the two middle-ranked classes (high-moderate-growing and low-fast-growing). For school engagement, children of immigrants were more likely to fall in the best (high-stable) and second-best (high-moderate-decreasing) classes, with a greater proportion of the second generation in the best class than the 1.5 generation. Concerning depression, very few 1.5-generation children belonged to high-decreasing. Second-generation children were more likely to be classified as moderate-decreasing and high-decreasing, however. These bivariate relationships did not take into account other background information, including race and SES, that may heavily influence individuals’ developmental trajectory.

Table 3.

Proportion or Mean of Covariates in Trajectory Classes: Add Health and AHAA

| Academic Achievement | School Engagement | Depression | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Covariate | Total | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 |

| 1.5 generation | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.074 | 0.073 | 0.055 | 0.066 | 0.088 | 0.205 | 0.047 | 0.067 | 0.073 | 0.028 | 0.071 |

| 2nd generation | 0.123 | 0.136 | 0.114 | 0.098 | 0.117 | 0.121 | 0.186 | 0.142 | 0.101 | 0.114 | 0.161 | 0.166 | 0.123 |

| Black | 0.197 | 0.152 | 0.223 | 0.374 | 0.226 | 0.187 | 0.262 | 0.295 | 0.224 | 0.186 | 0.242 | 0.158 | 0.235 |

| Hispanic | 0.150 | 0.102 | 0.181 | 0.198 | 0.212 | 0.138 | 0.226 | 0.295 | 0.181 | 0.141 | 0.179 | 0.194 | 0.172 |

| Asian | 0.071 | 0.099 | 0.055 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.074 | 0.091 | 0.097 | 0.033 | 0.068 | 0.086 | 0.097 | 0.062 |

| Female | 0.529 | 0.569 | 0.513 | 0.508 | 0.421 | 0.544 | 0.385 | 0.568 | 0.490 | 0.480 | 0.677 | 0.798 | 0.643 |

| Age at 9th grade | 14.396 | 14.279 | 14.421 | 14.511 | 14.815 | 14.343 | 14.433 | 14.267 | 14.783 | 14.386 | 14.428 | 14.405 | 14.426 |

| Parent education | 14.002 | 14.837 | 13.554 | 13.034 | 12.521 | 14.242 | 13.175 | 13.102 | 12.813 | 14.107 | 13.675 | 13.717 | 13.706 |

| 2-parent family | 0.573 | 0.677 | 0.517 | 0.391 | 0.412 | 0.610 | 0.465 | 0.358 | 0.389 | 0.595 | 0.530 | 0.417 | 0.483 |

| Public school | 0.927 | 0.884 | 0.953 | 0.980 | 0.985 | 0.920 | 0.961 | 0.977 | 0.949 | 0.921 | 0.946 | 0.951 | 0.933 |

| Attendance rate | 0.920 | 0.926 | 0.916 | 0.908 | 0.914 | 0.922 | 0.904 | 0.908 | 0.913 | 0.921 | 0.916 | 0.917 | 0.918 |

The distribution of most other covariates across trajectory classes was as expected. For example, the proportion of Hispanic decreased while the proportion of Asians increased with the top-down rank of academic achievement trajectory classes. Higher parental education, two-parent families, private high school, and higher attendance rates were associated with better developmental trajectories. And, being a young female was strongly associated with high initial depression.

Does Generation Status Matter in Distinct Trajectory Classes?

We hypothesized that children of immigrants, particularly the 1.5 generation, are advantaged in academic achievement and school engagement but are susceptible to depression. We now discuss whether these hypotheses can be supported by examining how generation status influenced respondents’ propensity of belonging to a distinct trajectory class, as well as how generation status affected the growth factors of trajectories.

Table 4 shows the coefficients (log odds) for covariates in predicting memberships in the normatively best, second-best, and third-best latent classes versus the worst class in academic achievement, school engagement, and depression, respectively. We focused on the results for the 1.5 generation and second generations, with the third generation as the reference, controlling for other covariates. Compared to the third generation, 1.5-generation children were more likely to fall in the first three classes of academic achievement trajectories vs. the worst trajectory class. The 1.5 generation’s odds were 2.22 (e.799 ) times that of their third-generation counterparts to be a member of high-fast-growing, 2.14 times more likely to belong to high-moderate-growing, and 2.09 times more likely to fall in low-fast-growing. The second generation was similarly advantaged in the best class, but had no advantage in either the second- or third-best class, with the worst class as the reference. Given that the best class (high-fast-growing) included almost half of the sample, the evidence largely supported H1, which predicted that children of immigrants would be less likely to fall in the worst class (low-minimal-growing). Compared to the third generation, 1.5-generation children were more likely to follow the low-fast-growing trajectory, supporting H1a, which predicted that they would improve academically as they stayed in the United States longer. Given their better English skills and acculturation, the second generation was hypothesized to cluster more densely in the high-fast-growing class than the 1.5 generation, but we found no significant difference between the 1.5 and second generations in this regard, failing to support H2b.

Table 4.

Estimates for Covariates for Membership in a Better vs. the Worst Class: Add Health and AHAA

| Latent trajectory class |

Academic Achievement |

School Engagement |

Depression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best vs. worst | |||

| 1.5 generation | 0.799 * | 0.620 ** | −0.010 |

| 2nd generation | 0.603 ** | 0.230 | −0.058 |

| Black | −0.275 * | 0.084 | −0.203 |

| Hispanic | −0.759 ** | −0.303 * | −0.210 |

| Asian | 0.154 | 0.115 | −0.030 |

| Female | 0.660 ** | 0.191 ** | −0.683 ** |

| Age at 9th grade | −1.103 ** | −0.877 ** | −0.126 |

| Parental education | 0.340 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.042 * |

| Two-parent family | 0.694 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.369 ** |

| Public school | −1.605 ** | −0.056 | 0.061 |

| School attendance | 3.523 * | 4.931 ** | 0.402 |

| School class size | −0.016 | 0.019 ** | −0.012 |

| Second best vs. worst | |||

| 1.5 generation | 0.761 ** | 0.704 ** | 0.001 |

| 2nd generation | 0.246 | 0.519 ** | 0.280 |

| Black | 0.016 | 0.410 ** | 0.103 |

| Hispanic | −0.366 * | −0.081 | −0.030 |

| Asian | −0.176 | 0.315 | 0.322 |

| Female | 0.392 ** | −0.491 ** | 0.079 |

| Age at 9th grade | −0.785 ** | −0.740 ** | 0.027 |

| Parental education | 0.167 ** | 0.050 * | 0.000 |

| Two-parent family | 0.279 ** | 0.199 | 0.197 |

| Public school | −1.075 ** | 0.173 | 0.242 |

| School attendance | 0.607 | −1.869 | −0.479 |

| School class size | 0.005 | 0.034 ** | −0.007 |

| Third best vs. worst | |||

| 1.5 generation | 0.736 * | 1.610 ** | −1.102 |

| 2nd generation | 0.197 | 0.313 | −0.021 |

| Black | 0.767 ** | 0.901 ** | −0.494 |

| Hispanic | 0.086 | 0.409 | 0.237 |

| Asian | −0.388 | 0.403 | 0.795 * |

| Female | 0.277 | 0.142 | 0.705 ** |

| Age at 9th grade | −0.623 ** | −1.187 ** | 0.004 |

| Parental education | 0.093 * | 0.066 | 0.017 |

| Two-parent family | −0.029 | −0.232 | −0.253 |

| Public school | −0.166 | 0.666 | 0.253 |

| School attendance | −1.349 | 1.868 | 0.616 |

| School class size | −0.011 | 0.023 | 0.012 |

p < .05

p < .01

We hypothesized that children of immigrants would be less likely to belong to the worst class of school engagement (H2). The best class (high-stable) favored only the 1.5 generation, whereas the second best class (high-moderate-decreasing) favored both 1.5 and second generations. Because the best class counted over 80% of all children while the second-best class only 6%, the evidence supports H2 fully for the 1.5 generation but only supports it partially for the second generation. In turn, the evidence supports H1a, which predicted a greater advantage for the 1.5 generation than for the second generation. In addition, the 1.5 generation was more likely to turn around from low engagement to high engagement over time. Even though it affected only 1.6% of the sample, this pattern is still substantively important in revealing resilience for those who were initially disadvantaged.

We proposed that migration, adaptation, and assimilation would raise the stress level and place children of immigrants at varying risks of depression across generations (H3, H3a, and H3b). The third column of Table 4 shows that no significant effects for generation status were detected, suggesting that the advantages for children of immigrants in academic achievement and school engagement were not compromised by the hypothesized poorer mental health.

Putting the findings for generation status in the context of other covariates, we see that, in general, being white, female, young, with higher parental education, residing in two-parent family, attending private school, and attending a high school with a high attendance rate all yielded positive, significant effects on students’ membership propensity toward attaining better academic achievement and school-engagement classes. The effects of children of immigrant status, especially the 1.5 generation status, were substantial in comparison to other factors.

Table 5 also shows the regression estimates for covariates on intercepts and slopes. The 1.5 generation had an additional advantage in raising the intercepts of school-engagement trajectories, pushing up the slopes of academic-achievement trajectories, and pressing down the slopes of depression trajectories. All these effects worked toward bettering developmental outcomes. The second generation, however, did not exhibit a similarly beneficial impact on growth factors.

Table 5.

Estimates for Covariates on Growth Factors: Add Health and AHAA

| Growth Factor | Academic Achievement | School Engagement | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | |||

| 1.5 generation | −0.041 | 0.018 ** | 0.049 |

| 2nd generation | 0.058 | 0.005 | −0.001 |

| Black | −0.104 ** | −0.032 ** | −0.008 |

| Hispanic | −0.148 ** | −0.027 ** | 0.030 |

| Asian | −0.037 | 0.007 | 0.087 ** |

| Female | 0.057 ** | 0.023 ** | 0.022 * |

| Age at 9th grade | −0.007 | −0.014 ** | 0.021 * |

| Parental education | 0.042 ** | 0.006 ** | −0.014 ** |

| Two-parent family | 0.046 ** | 0.011 ** | −0.030 ** |

| Public school | −0.038 | −0.014 ** | −0.013 |

| School attendance | 0.589 | 0.271 ** | −0.543 ** |

| School class size | −0.015 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Slope | |||

| 1.5 generation | 0.074 ** | −0.003 | −0.012 * |

| 2nd generation | 0.022 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| Black | 0.030 ** | 0.008 ** | 0.003 |

| Hispanic | 0.014 | 0.006 ** | −0.005 |

| Asian | 0.052 ** | −0.004 | −0.011 * |

| Female | −0.014 | −0.006 ** | 0.006 ** |

| Age at 9th grade | −0.042 ** | 0.003 ** | −0.001 |

| Parental education | 0.005 ** | −0.001 ** | 0.002 ** |

| Two-parent family | 0.018 * | −0.002 | 0.002 |

| Public school | −0.021 | 0.003 * | 0.004 |

| School attendance | 0.013 | −0.059 ** | 0.088 ** |

| School class size | 0.004 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

p < .05

p < .01

To test the hypothesis of a weaker generation advantage for Hispanic children than for Asian children (H4), we entered interaction terms of generation status with each racial-ethnic group in the models for academic achievement, school engagement, and depression. None of these models converged because of small cell sizes for the first generation within whites and blacks and the second generation within blacks. To overcome this problem, we combined the 1.5 and second generations into a single immigrant status and found no significant differences in the advantage of immigrant status between Hispanics and Asians. Thus no evidence was found to support the modified H4, which proposed that the advantage for 1.5 and second generations combined would be weaker for Hispanics than for Asians.

Trajectory Classes, Generational Status, and Young-Adult Outcomes

If the 1.5 generation and, to a lesser degree, the second generation are more likely to be in the normatively better trajectories of academic achievement and school engagement, and if these better trajectories significantly enhance young-adult outcomes, we are more confident that children of immigrants have an advantage in transition to adulthood. Table 6 presents the estimates for distinct trajectories in the cognitive, social-behavior, and mental-health domains on a young-adult outcome in the corresponding domain—years of schooling, earned academic degree, and psychological well-being. Concerning the within-domain transition, high-fast-growing academic achievement during adolescence brings about more years of schooling and produces a greater probability of obtaining a higher degree; the effect of the second-best academic achievement class on young-adult educational outcomes was positive but weaker; and a further weaker relationship was found for the third-best class. Youth’s low-stable and moderate-decreasing forms of depression were related to greater psychological well-being in young adulthood, but there was no statistical difference in the effects of high-decreasing and low-increasing depression. Concerning the between-domain transition, the best academic-achievement class promoted psychological well-being. The best engagement trajectory class had a positive effect on all three young adult outcomes. The effects on educational outcomes of both high-moderate-decreasing and low-increasing school engagement were weaker than the best trajectory class, but low-increasing engagement yielded a stronger effect than high-moderate-decreasing engagement. Low-increasing engagement also promoted psychological well-being. Low-stable and moderate-decreasing forms of depression were positively related with years of schooling and earned academic degree. Overall, the findings on within- and between-domain transitions reaffirmed the advantage for children of immigrants in following the better adolescent trajectories that promote young-adult success.

Table 6.

Estimates for Distinct Adolescent Trajectories in Young Adult Outcomes: Add Health and AHAA

| Variable | Educational Attainment | Academic Degree | Psychological Well-being |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic achievement | |||

| High-fast-growing | 2.167 ** | 2.235 ** | 0.087 ** |

| High-moderate-growing | 0.877 ** | 0.949 ** | 0.027 |

| Low-fast-growing | 0.591 ** | 0.543 ** | −0.018 |

| School engagement | |||

| High-stable | 1.197 ** | 2.475 ** | 0.098 ** |

| High-moderate-decreasing | 0.351 ** | 1.303 ** | −0.009 |

| Low-increasing | 0.720 ** | 1.963 ** | 0.120 * |

| Depression | |||

| Low-stable | 0.329 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.506 ** |

| Moderate-decreasing | 0.157 * | 0.256 ** | 0.250 ** |

| High-decreasing | 0.085 | 0.062 | 0.021 |

| Covariate | |||

| 1.5 generation | 0.357 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.072 * |

| 2nd generation | 0.427 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.046 |

| Black | 0.107 * | 0.050 | −0.072 ** |

| Hispanic | −0.054 | −0.083 | 0.004 |

| Asian | −0.015 | −0.070 | −0.137 ** |

| Female | 0.405 ** | 0.431 ** | −0.040 ** |

| Age at 9th grade | 0.059 ** | 0.082 ** | 0.006 |

| Parental education | 0.211 ** | 0.211 ** | 0.006 * |

| Two-parent family | 0.164 ** | 0.270 ** | 0.058 ** |

| Not observed in Wave IV | −0.720 ** | −1.015 ** | −0.008 |

| _cons | 6.879 ** | −0.777 ** |

p < .05

p < .01

Table 6 also shows the continuously significant effects of generation status on young-adult outcomes after controlling for distinct adolescent trajectories. To interpret these direct generational status effects above the mediating effects via distinct trajectories, we considered individual agency between the end of adolescent trajectories and the time when young-adult outcomes were measured (8-13 years for academic achievement and school engagement and 6 years for depression). During this period, youth exited the secondary-education institution and parental family and community while entering higher education, the labor market, a family of procreation, a community of own residence, and civic and cultural organizations for youth. New institutional rules and regulations embedded in the broader social stratification require different individual agency to become successful. It is in these new social spheres that 1.5 and second generations would benefit from their greater success-orientation and cultural between-ness, captured in the direct positive effects on young-adult outcomes.

Conclusions

Prior examinations of advantages for children of immigrants have generally ignored distinct developmental trajectories during adolescence and their role in the transition to adulthood. Thus, we know relatively little about how generation status influences distinct trajectories of adolescent development and how adolescent trajectories might affect young adult outcomes. Filling these gaps is important, as the ever-growing numbers of 1.5- and second-generation children are fast coming of age, and we want to know how they will fare in comparison to the third generation.

This paper extended the literature on three fronts. First, we treated individual longitudinal outcomes in a domain as a unitary whole in the form of trajectories, which were allowed to be distinct across subpopulations. Second, we examined cognitive, socio-behavioral, and psychological domains, represented by academic achievement, school engagement, and depression, respectively. Third, we examined the young-adult consequences of the identified distinct trajectories. With these extensions, we were in a better position to test the hypotheses regarding the advantages for children of immigrants derived from existing theories and research.

Our study, however, is not without limitations. First, we lacked in-depth information on nuanced social contexts, such as the characteristics of co-ethnic immigrant communities, which would be critical in further differentiating 1.5 and second generations. Second, our analytic approach placed a heavy demand on the data. Our data on an analytical sample of nearly 11,000 individuals observed at 3-4 time points still do not allow for an estimation of the fully unrestricted model. Therefore, we imposed a number of constraints that have been common to studies of our kind. These constraints may have affected the accuracy of our estimates. Third, while our analytic sample included sufficient 1.5- and second-generation Hispanic subsamples, the corresponding sizes for Asians and blacks, as well as national-origin groups, were too small to produce reliable estimates. Fourth, the measure of school engagement from transcript data could be improved if raw data on individual attendance were available. We remain cautious about the potential oversimplification of our analysis.

With this caveat, our analysis offered three major findings. First, we found evidence to support the hypothesized differential advantage between children of immigrants and the third generation, controlling for background variables. But, even within children of immigrants, we found a significant differential advantage between the 1.5 and second generations. Specifically, compared to the third generation, 1.5-generation children were more likely to follow the normatively best and second-best trajectories of academic achievement and school engagement, whereas second-generation children were more likely to take the second-best trajectory of academic achievement. In addition, 1.5 generation status had a positive effect on growth factors. Second, we did not find evidence for any disadvantage for children of immigrants in depression as hypothesized. The advantage for children of immigrants in the cognitive and socio-behavioral domains was not compromised by a proneness to depression. Third, no evidence was detected for the hypothesized smaller 1.5-generation advantage for children of Hispanic origin. We conclude that, controlling for race-ethnicity, SES, gender, age, parental education, family structure, and school conditions, 1.5-generation children possess a significant advantage over the third generation in the cognitive and socio-behavioral domains, while second-generation children possess relatively less significant advantage, limited just to the cognitive domain.

Our findings suggest room for theory improvements. The identified 1.5 generation advantage begs a question about the importance of pre-migration experience in the current framework of assimilation theory. The micro processes in existing theories have focused on those in the host society, which is appropriate for the second generation but not for the 1.5 generation. Adding the 1.5 generation’s socialization and life experiences in the origin country would complete the micro processes from pre-migration to post-migration within the macro contexts that include both exit from the home country and reception in the host country. Our findings also suggest that the promoting effect of immigrant optimism and the protective effect of immigrant families and co-ethnic communities are contingent on whether children’s ethnic-identity formation and development occur across the borders of or within the host society. The post-migration identity development of the 1.5 generation may differ from that of the second generation within the same family, community, and school contexts in the host society. In addition, the agency argument for 1.5- and second-generation children can be strengthened by taking into account life-course development in both the home and host society in explaining how cultural between-ness is used to promote developmental outcomes.

We also wish to push developmental research in a more holistic direction. Paying close attention to the multi-domain developmental process in multi-level contexts for the increasingly diverse adolescent population will advance our accurate understanding of today’s adolescent development. Qualitative studies have employed holistic views, but much quantitative research still takes the phenomenon under study in separate pieces. Although there is always a tension between the elegance and cost of simplicity, the principle of parsimony does not equate simplicity at the expense of losing sight. Our study shows that a balance can be reached. Large-scale national longitudinal data and statistical tools, such as the growth mixture modeling, are available to facilitate a holistic approach via trajectory analyses in multiple domains.

Our findings also provide fresh evidence for policy makers who are concerned with the quality of immigrant generations and the skill composition of the future American labor force. The advantage for the 1.5 generation and, to a lesser degree, the second generation, as well as the absence of disadvantage in depression for children of immigrants, all help project the future quality of the American labor force and skill composition. This projection can serve as the basis for designing relevant education and labor-force policies in the United States. Implications can also be extended to policies that aim to find protective factors for disadvantaged subpopulations via looking into the process by which 1.5-generation children are resilient despite their lower socioeconomic and racial-minority backgrounds.

Table 1.

Growth Mixture Model Selection: Add Health and AHAA

| No. of Latent Classes | No. of Parameters | AIC | BIC | Mean Prob. | LMR LRT(df) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Achievement | ||||||

| 2 | 46 | 96,595 | 96,930 | (.864, .903) | 3,436(15) | 0.0000 |

| 3 | 61 | 93,820 | 94,264 | (.863, .898) | 2,785(15) | 0.0000 |

| 4 | 76 | 92,057 | 92,610 | (.886, .916) | 1,781(15) | 0.0000 |

| School Engagement | ||||||

| 2 | 46 | −37,739 | −37,403 | (.995, .999) | 18,408(15) | 0.0000 |

| 3 | 61 | −43,437 | −42,992 | (.964, .999) | 5,687(15) | 0.0000 |

| 4 | 76 | −45,250 | −44,696 | (.925, .999) | 1,836(15) | 0.0000 |

| Depression | ||||||

| 2 | 45 | 43,778 | 44,106 | (.853, .964) | 2,235(15) | 0.0000 |

| 3 | 60 | 40,430 | 40,867 | (.844, .962) | 2,278(15) | 0.0000 |

| 4 | 75 | 40,154 | 40,700 | (.836, .939) | 304(15) | 0.0000 |

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. This research also uses data from the AHAA study, which was funded by a grant (R01 HD040428-02, Chandra Muller, PI) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a grant (REC-0126167, Chandra Muller, PI, and Pedro Reyes, Co-PI) from the National Science Foundation, and was also supported by grant, 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development. Opinions reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies. This research was supported in part by an NICHD training grant to the Hopkins Population Center at Johns Hopkins University (5T32HD007546-10). This paper benefited from the discussion at the Sociology Colloquium, University of Pennsylvania.

Appendix Table.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables Used in Analysis by Generation Status: Add Health and AHAA

| Variable | Total | 1.5 Generation | 2nd Generation | 3rd Generation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Adolescent outcome | ||||||||

| Math-sci level at t0 | 3.116 | 1.221 | 2.901 | 1.217 | 3.002 | 1.253 | 3.151 | 1.214 |

| Math-sci level at t1 | 3.897 | 1.146 | 3.851 | 1.134 | 3.957 | 1.155 | 3.892 | 1.145 |

| Math-sci level at t2 | 4.481 | 1.288 | 4.497 | 1.238 | 4.556 | 1.308 | 4.468 | 1.289 |

| Math-sci level at t3 | 4.866 | 1.446 | 4.968 | 1.398 | 4.999 | 1.475 | 4.837 | 1.444 |

| Sch. Engagement at t0 | 0.926 | 0.178 | 0.922 | 0.211 | 0.928 | 0.174 | 0.926 | 0.175 |

| Sch. Engagement at t1 | 0.900 | 0.218 | 0.898 | 0.229 | 0.891 | 0.217 | 0.901 | 0.217 |

| Sch. Engagement at t2 | 0.872 | 0.265 | 0.897 | 0.225 | 0.870 | 0.255 | 0.870 | 0.269 |

| Sch. Engagement at t3 | 0.850 | 0.314 | 0.874 | 0.272 | 0.853 | 0.294 | 0.848 | 0.320 |

| Depression at t0 | 0.616 | 0.554 | 0.708 | 0.523 | 0.691 | 0.580 | 0.597 | 0.551 |

| Depression at t1 | 0.602 | 0.551 | 0.692 | 0.527 | 0.681 | 0.574 | 0.583 | 0.547 |

| Depression at t6 | 0.378 | 0.548 | 0.374 | 0.546 | 0.379 | 0.545 | 0.378 | 0.548 |

| Young-adult outcome | ||||||||

| Years of schooling | 14.383 | 2.157 | 14.457 | 2.123 | 14.648 | 2.209 | 14.336 | 2.150 |

| No degree | 0.039 | 0.193 | 0.045 | 0.208 | 0.044 | 0.204 | 0.037 | 0.189 |

| GED | 0.050 | 0.218 | 0.029 | 0.168 | 0.045 | 0.208 | 0.052 | 0.223 |

| H.s. diploma | 0.412 | 0.492 | 0.383 | 0.486 | 0.358 | 0.480 | 0.423 | 0.494 |

| AA and voc | 0.177 | 0.381 | 0.197 | 0.398 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0.172 | 0.378 |

| Bachelor’s | 0.241 | 0.428 | 0.260 | 0.439 | 0.255 | 0.436 | 0.237 | 0.425 |

| Master’s and cert. | 0.063 | 0.243 | 0.063 | 0.244 | 0.076 | 0.265 | 0.061 | 0.240 |

| Advanced | 0.019 | 0.137 | 0.022 | 0.147 | 0.029 | 0.167 | 0.017 | 0.130 |

| Psychological well-being | 0.032 | 0.733 | 0.064 | 0.719 | 0.049 | 0.717 | 0.027 | 0.736 |

| Covariate | ||||||||

| 1.5 generation | 0.067 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2nd generation | 0.123 | 0.329 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 3rd generation | 0.810 | 0.393 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| White | 0.581 | 0.493 | 0.050 | 0.217 | 0.189 | 0.392 | 0.685 | 0.465 |

| Black | 0.197 | 0.398 | 0.037 | 0.189 | 0.059 | 0.236 | 0.232 | 0.422 |

| Hispanic | 0.150 | 0.357 | 0.485 | 0.500 | 0.510 | 0.500 | 0.068 | 0.252 |

| Asian | 0.071 | 0.257 | 0.428 | 0.495 | 0.241 | 0.428 | 0.016 | 0.124 |

| Male | 0.471 | 0.499 | 0.514 | 0.500 | 0.496 | 0.500 | 0.463 | 0.499 |

| Female | 0.529 | 0.499 | 0.486 | 0.500 | 0.504 | 0.500 | 0.537 | 0.499 |

| Age at 9th Grade | 14.396 | 0.606 | 14.442 | 0.694 | 14.268 | 0.563 | 14.412 | 0.603 |

| Age in 2007 | 27.422 | 2.324 | 27.727 | 2.591 | 27.449 | 2.371 | 27.392 | 2.291 |

| Parental education | 14.002 | 2.469 | 13.540 | 2.929 | 13.532 | 2.798 | 14.112 | 2.359 |

| Two-parent family | 0.573 | 0.495 | 0.667 | 0.472 | 0.731 | 0.444 | 0.541 | 0.498 |

| Public school | 0.927 | 0.261 | 0.975 | 0.156 | 0.935 | 0.247 | 0.922 | 0.269 |

| School attendance rate | 0.920 | 0.039 | 0.908 | 0.037 | 0.910 | 0.037 | 0.923 | 0.039 |

| School ave. class size | 26.581 | 5.552 | 30.899 | 5.438 | 29.923 | 6.162 | 25.714 | 5.085 |

| Attritted in Wave 4 | 0.126 | 0.332 | 0.215 | 0.411 | 0.153 | 0.360 | 0.115 | 0.319 |

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Pan J, Jun H, Osypuk TL, Emmons KM. The effect of immigrant generation on smoking. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1223–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderman EM, Maehr ML, Midgley C. Declining motivation after the transition to middle school: schools can make a difference. Journal of Research and Development in Education. 1999;32:131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Brindis C, Wolfe AL, McCarter V, Ball S, Starbuck-Morales S. The associations between immigrant status and risk-behavior patterns in Latino adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00101-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SJ, Meadows SO, Elder GH., Jr Race-ethnic inequality and psychological distress: Depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1295–1311. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. The Diverse Experiences of Hispanic Students in the American Educational System Sociological Forum. 2005;20(4):561–588. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Russell ST, Crockett LJ. Parenting styles and youth well-being across immigrant generations. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr. Life Course and Human Development. In: Damon William., editor. Handbook of Child Psychology. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 939–91. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert L, Thompson E, Randell B, Pike K. Preliminary effects of brief school-based prevention approaches for reducing youth suicide- risk behaviors, de pres~ i on, and drug involvement. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2002;15(2):48–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2002.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Slusarcick AL. Paths to High School Graduation or Dropout: A Longitudinal Study of a First-Grade Cohort. Sociology of Education. 1992;65:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. First Grade and Educational Attainment by Age 22: A New Story. American Journal of Sociology. 2005;110:1458–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: The roles of family background, attitudes, and behavior. Child Development. 1997;68:351–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Boyle MH, Duku E. Contextual Influences on Children’s Mental Health and School Performance: The Moderating Effects of Family Immigrant Status. Child Development. 2007;78(5):1572–1591. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick JE, White MJ. The academic trajectories of immigrant youth: Analysis within and across cohorts. Demography. 2003;40:759–784. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair EC, Moore KA, Hunter D, Kaye JW. Youth Outcomes Compendium. Child Trends and the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Bonstead-Bruns M. Parent-Child Difference in Educational Expectations and Academic Achievement of Immigrant and Native Students. Sociology of Education. 1998;71:175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Ma Y. Immigrant Youth in Postsecondary Education. In: Coll Cynthia Garcia, Marks Amy., editors. Is Becoming an American a Developmental Risk? American Psychological Association Book Center; (forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Pong S. The Role of School in Upward Mobility of Disadvantaged Immigrants’ Children. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;620(1):62–89. doi: 10.1177/0002716208322582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harker K. Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological well-being. Social Forces. 2001;79:969–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM. The health status and risk behavior of adolescents in immigrant families. In: Hernandez DJ, editor. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 286–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ. Demographic change and the life circumstances of immigrant families. Future of Children. 2004;14:17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G, Rosenzweig MR. Self-selection and the earning of immigrants: Comment. American Economic Review. 1990;80:298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Phillips M. The Black-white test score gap. Brookings Institution Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz P, Mollenkopf JH, Waters MC, Holdaway J. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. Harvard University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G. Parental Influences on the Educational Outcomes of Immigrant Youth. International Migration Review. 2004;38:427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Tienda M. Optimism and achievement: the educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE. Theories of international migration: Review and appraisal. Population and Development Review. 1993;19:431–66. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Fettes DL. Trajectories of Failure: The EducationalCareers of Children with Mental Health Problems. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;113:653–701. doi: 10.1086/521849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeeley CA, Nonnemaker JM, Blum RW. Promoting School Connectedness: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health. 2002;72:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite Mixture Modeling with Mixture Outcomes Using the EM Algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris KM, Bollen K. What Are We Measuring? An Evaluation of the CES-D across Race/Ethnicity and Immigrant Generation, Social Forces. 2005;83(4):1567–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. University of California Press and Russell Sage Foundation; Berkeley and New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Zhou M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1993;530:74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Roderick M, Arney M, Axelman M, DaCosta K, Steiger C, Stone S, Waxman E. Research brief. University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration; Chicago, IL: 1997. Habits hard to brea k: A new look at truancy in Chicago’s public high schools. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush S. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:224–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapiro NA. Issues of separation and reunification in immigrant Latina youth. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2002;37(3):381–92. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(02)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Vollebergh WAM. Mental health in migrant children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:276–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M, Kim HK, Capaldi D. The Course of Depressive Symptoms in Men From Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Identifying Latent Trajectories and Early Predictors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(3):331–345. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Okazaki S. Asian-American educational achievements: a phenomenon in search of an explanation. American Psychology. 1990;45:913–20. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Larose S, Tremblay RE. Kindergarten Disruptive Behaviors, Protective Factors, and Educational Achievement by Early Adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:617–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner MM. Outcomes for Youths with Serious Emotional Disturbance in Secondary School and Early Adulthood. Future of Children. 1995;5:90–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC, Tran VC, Kasinitz P, Mollenkopf JH. Segmented assimilation revisited: types of acculturation and socioeconomic mobility in young adulthood. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2010;33(7):1168–1193. doi: 10.1080/01419871003624076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation. Temple University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]