Abstract

Objective

To determine the frequency, mortality, cost and risk factors associated with readmission after index hospitalization with severe sepsis.

Design

Observational cohort study of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) data.

Setting

All non-federal hospitals in 3 U.S. states.

Patients

Severe sepsis survivors (n = 43,452) in the first 2 quarters of 2011.

Measurements and Main Results

We measured readmission rates and the associated cost and mortality of readmissions in severe sepsis survivors. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with readmission. Of 43,452 sepsis survivors, 26% required readmission within 30 days and 48% within 180 days. The cumulative mortality rate of sepsis survivors attributed to readmissions was 8% and the estimated cost was over $1.1 billion. Among survivors, 25% required multiple readmissions within 180 days and accounted for 77% of all readmissions. Age < 80 (Odds Ratio [OR], 1.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–1.21), black race (OR 1.18, 1.10–1.26), and Medicare or Medicaid payor status (OR 1.21, 1.13–1.30; OR 1.34, 1.23–1.46, respectively) were associated with greater odds of 30-day readmission while female gender was associated with reduced odds (OR 0.92, 0.87–0.96). Comorbidities including malignancy (OR 1.34, 1.24–1.45), collagen vascular disease (OR 1.30, 1.15–1.46), chronic kidney disease (OR 1.24, 1.18–1.31), liver disease (OR 1.22, 1.11–1.34), congestive heart failure (OR 1.14, 1.08–1.19), lung disease (OR 1.12, 1.06–1.18), and diabetes (OR 1.12, 1.07–1.17) were associated with greater odds of 30-day readmission. Index hospitalization characteristics including longer length of stay, discharge to a care facility, higher hospital annual severe sepsis case volume, and higher hospital sepsis mortality rate were also positively associated with readmission rates.

Conclusion

30-day and 180-day readmissions are common in sepsis survivors with significant resultant cost and mortality. Patient socio-demographics and comorbidities as well as index hospitalization characteristics are associated with 30-day readmission rates.

Keywords: Sepsis, Survivors, Patient Readmission, Critical Illness, Comorbidity, Risk Factors

Introduction

Hospital readmissions are common and have far-reaching implications for patients and society(1). Approximately 20% of discharged Medicare beneficiaries are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge while 34% are rehospitalized within 90 days(2). Readmissions impact quality of life and represent a significant cost burden to the United States (U.S.) healthcare system with annual costs estimated to be $17 billion in Medicare recipients alone(2). Hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge has been associated with substandard care during the index admission(3) and inadequate post-discharge care processes(4). This has led to the assertion that a proportion of readmissions are avoidable although estimates of this proportion vary widely(5). Accordingly, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has mandated that hospitals reduce readmissions for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Starting in 2013, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services began tying reimbursement rates for all diagnosis related groups to the readmission rates for these common and costly diagnoses(2, 6).

Similarly, severe sepsis is a disease of high prevalence and cost. Evaluation of Medicare claims shows an increasing incidence of severe sepsis with over 1 million annual admissions(7) while the total annual cost of sepsis admissions now exceeds $20 billion in the U.S.(8). Approximately 850,000 Medicare patients survived admission for severe sepsis in 2008(7), representing a large population at risk of hospital readmission given large comorbidity burdens(9) and adverse cognitive and functional sequelae(10). Despite the size and fragility of this population, little is known about its readmission rates or their associated cost and risk factors.

Quantifying the scope of readmissions in severe sepsis survivors and identifying risk factors may inform policy and facilitate identification of high risk patients for future targeted intervention. Thus, we evaluated readmission patterns, potential risk factors, and cost after an index admission with severe sepsis in a large administrative database. The objectives of this study were to 1) quantify the frequency of 30-day readmissions in severe sepsis survivors, 2) identify associations between patient and/or index hospitalization characteristics and readmissions, and 3) determine whether readmissions are a frequent problem beyond 30 days from discharge and estimate the costs associated with these readmissions.

Materials and Methods

Study Design/Data Source

We performed a retrospective cohort study of adults hospitalized with severe sepsis to non-federal hospitals in California, Florida and New York during the first two quarters of the calendar year 2011 using these states’ Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) state inpatient databases (SID). These states were chosen because their large size and geographic heterogeneity enhance the generalizability of the study’s findings and because their SIDs contain patient-level identifiers such that readmissions are traceable.

Severe Sepsis Cohort Identification

We identified all patients, ≥ age 20, who were admitted in Quarter 1 (Q1) or Quarter 2 (Q2) of 2011 and experienced severe sepsis and/or septic shock during this index admission. Index admissions were confined to Q1/Q2 to allow adequate time for a 180-day follow-up period. We defined this cohort by the presence of an International Classification of Disease, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52). This approach provides a highly specific severe sepsis cohort(11, 12) and, thus, a conservative estimate of severe sepsis survivors. While this approach has been historically limited by sensitivity, recent data demonstrate that the use of explicit severe sepsis and septic shock codes is increasingly common(13). We subsequently generated a severe sepsis survivor cohort by excluding patients who died during their index admission and those with missing data. Index hospitalizations that resulted in a transfer to another acute care hospital were counted as one admission rather than two episodes of care. In all cases of inter-hospital transfer, index hospital characteristics were attributed to the receiving hospital. Examination of a sample of the dataset revealed poor correlation between a discharge status of “transferred to another hospital” and a subsequent admission source of “transfer from another acute care hospital” suggesting a high rate of miscoding for these variables. Thus, in order to more comprehensively identify inter-hospital transfers, we considered any admission within 24 hours of discharge from a different hospital to be an inter-hospital transfer. If an individual had > 1 admission for severe sepsis in Q1/Q2, the first was considered the index admission while subsequent admissions were considered readmissions.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was readmission within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included readmission within 180 days of discharge, mortality associated with readmission, and costs associated with readmission.

Data Collection

The survivor cohort was analyzed for 180 days after the day of discharge as we hypothesized that severe sepsis survivors would be at risk for readmission beyond the 30 day window. Diagnoses, survival status, and charges associated with each readmission were captured. Readmission rates were calculated for 30-day intervals by dividing the number of survivors readmitted for the first time during the interval by the total survivor cohort. As our goal was to determine the percentage of the total sepsis survivor cohort (n = 43,425) who ultimately required readmission, we deliberately did not adjust the survivor cohort size to account for mortality during earlier intervals. The cumulative mortality rate attributed to readmissions was calculated for each interval by dividing deaths during readmission by the number of readmissions for each interval. The aggregate number of readmissions (initial and subsequent) was calculated for each time interval and their principal diagnoses were used to categorize the cause for each readmission using the HCUP Clinical Classification Software (CCS)(14–17). Cumulative costs for readmissions were calculated over the 180-day follow-up period by multiplying charge data from the SID dataset by hospital-specific HCUP cost-to-charge ratios. Patient-level characteristics including age, gender, race (black, non-hispanic white, hispanic, asian/pacific islander, native American or other), payor (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, dual-eligible or other), Charlson score(18) and Elixhauser comorbidities(19) were captured from index hospitalization records as were index hospitalization data including hospital length of stay (LOS), discharge destination, and acute organ failure rates. Organ failure was determined by a previously published method using ICD-9-CM codes to identify acute derangements in 7 different organ systems(9). As there is substantial evidence that readmissions are common after admission for pneumonia(2, 20, 21), we also captured the presence or absence of ICD-9-CM codes for pneumonia from the index admissions (Supplemental Digital Content - Appendix Table 1) in order to better understand the relative contribution that this diagnosis plays in severe sepsis readmissions and to determine if pneumonia is an independent risk factor for readmission among severe sepsis survivors. Finally, hospital-level characteristics including HCUP hospital type, annual severe sepsis case volume (categorized into tertiles: Low = <60 cases/yr., Intermediate = 60–300, High = >300) and annual severe sepsis mortality rate (categorized into quartiles: 1 = mortality < 27.3%, 2 = mortality 27.3–32.4%, 3 = mortality 32.5–38.2%, 4 = mortality > 38.2%) were also captured. The sepsis case volume tertile boundaries were chosen based on previous unpublished observations that severe sepsis mortality was influenced by these volume tertiles while the sepsis mortality quartile boundaries were chosen such that 25% of the patient sample fell within each quartile.

We further divided the readmission cohort into those who required one or multiple readmissions in order to understand the patterns and characteristics of the multi-readmissions population. The number and cost of readmissions for each sub-cohort were calculated.

Sensitivity Analysis

To account for variations in hospital coding practice, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a previously validated approach for defining a severe sepsis cohort from administrative data. Martin et al. used a combination of ICD-9-CM codes for septicemia, bacteremia, and fungal infection and codes for acute organ failure and validated its accuracy(9). The approach used to define our primary cohort has been shown to have similar positive and negative predictive values to the Martin approach(11). We compared our primary cohort to a cohort using the Martin approach and a third cohort using the Martin approach and/or the explicit ICD-9-CM codes for severe sepsis or septic shock. To evaluate for potential differences in readmission patterns when sepsis was present on admission (POA) versus not present on admission, we compared readmission rates and associated risk factors between patients in these two groups.

Statistical Analysis

We compared differences between readmission cohorts with chi-square analysis or student’s t test where appropriate. We used a manually fitted multivariable logistic regression to determine associations between patient and hospitalization characteristics and hospital readmission. Model construction began with patient demographics and then organ failures, comorbidities, and hospitalization characteristics were added one at a time. After the addition of each variable, the model was analyzed to determine if existing variables were still significant and if the model’s goodness of fit was affected according to the Akaike Information Criterion. Hospital-level clustering was controlled for using mixed effects modeling. Referent values for non-dichotomous covariates in the regression models include: non-Hispanic white race, commercial insurance, discharge to home, the lowest hospital case volume tertile, and the lowest hospital case mortality quartile. When age was examined as a continuous variable, it was found to have a non-linear relationship with readmission and an inflection point near age 80 above which the risk for readmission declined. Thus, age < 80 was added as a dichotomous variable to the model. For simplicity, the Elixhauser comorbidities for Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetes Mellitus with Complications were combined into one variable as were Lymphoma, Solid Tumor, and Metastatic Cancer. All presented odds ratios represent adjusted odds from the multivariable model. We used SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) for all analysis and considered a two-sided alpha 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Results

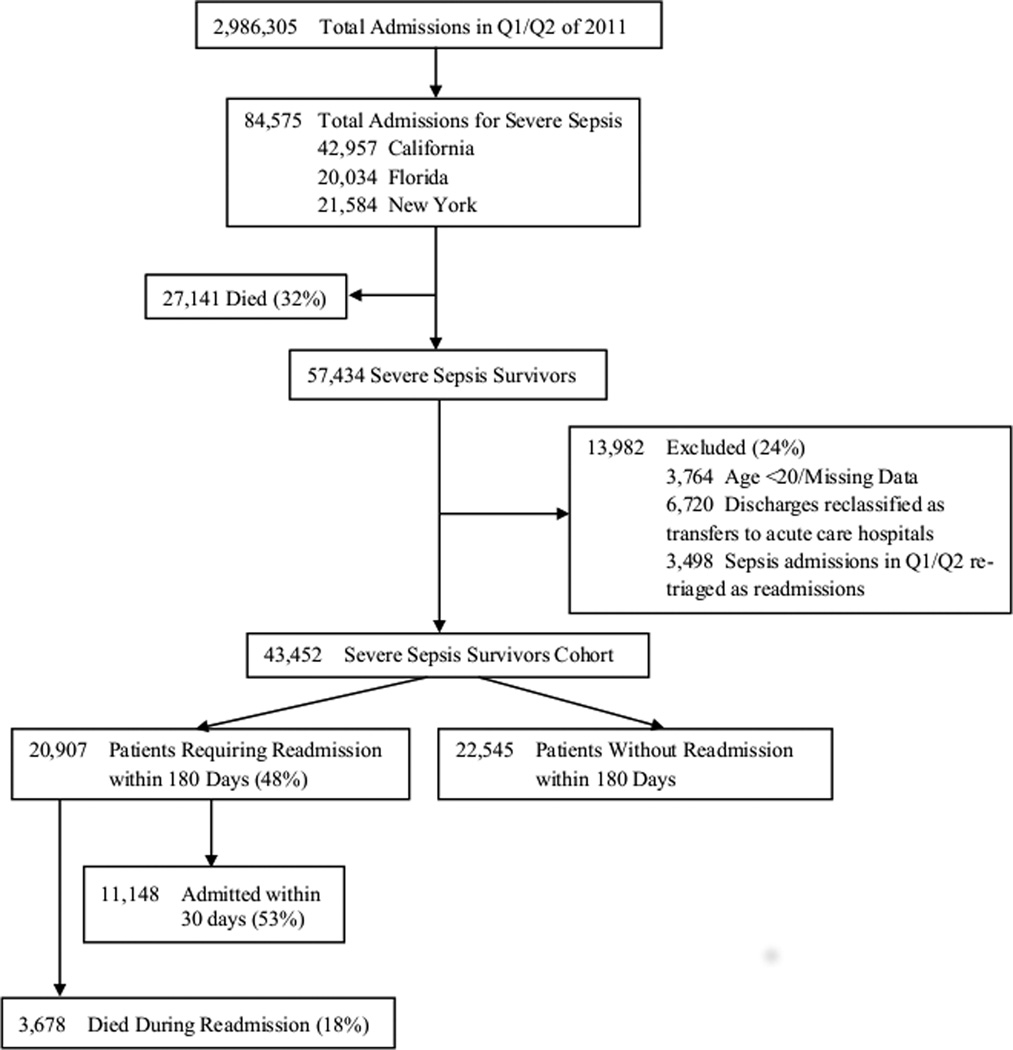

Of 2,986,305 admissions to non-federal hospitals in California, Florida, and New York, 84,575 were coded for severe sepsis (995.92) and/or septic shock (785.52) in Q1/Q2 of 2011 (Figure 1). Of these, there were 43,452 index admissions which met criteria for the severe sepsis survivor cohort. Over the 180-day follow-up period, 20,907 were readmitted resulting in 3,678 deaths (18%). Table 1 presents patient and index hospitalization characteristics of the entire survivor cohort and of the readmission and no readmission subgroups.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Analysis Cohort

Table 1.

Characteristics of Severe Sepsis Survivors.

| Total Sepsis Survivors Cohort N = 43,452 |

No Readmissions Cohort N = 22,545 |

Readmissions Cohort N = 20,907 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 69.0 (16.3) | 69.6 (16.7) | 68.3 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| % Female Gender | 48.9 | 49.6 | 48.1 | 0.0015 |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| % White | 62.6 | 65.0 | 60.0 | |

| % Black | 12.6 | 10.6 | 14.9 | |

| % Hispanic | 14.6 | 14.0 | 15.2 | |

| % Other | 10.2 | 10.4 | 9.9 | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | |||

| % Medicare | 65.1 | 64.6 | 65.5 | |

| % Medicaid | 12.7 | 11.6 | 14.1 | |

| % Dual Eligible | 4.8 | 4.1 | 5.6 | |

| % Commercial | 12.5 | 13.8 | 11.1 | |

| % Other | 4.9 | 5.9 | 3.7 | |

| Charlson Score (SD) | 2.9 (2.3) | 2.79 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Mean Hospital LOS in days (SD) | 15.9 (18.5) | 14.0 (16.3) | 17.9 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| Discharge Location | <0.001 | |||

| % Home | 52.1 | 54.2 | 49.7 | |

| % Care Facility | 40.8 | 33.2 | 49.0 | |

| % Hospice | 7.1 | 12.6 | 1.3 | |

| Organ Failures | 0.0019 | |||

| % 1 | 41.6 | 42.3 | 40.9 | |

| % 2 | 32.6 | 31.8 | 33.5 | |

| % 3 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 17.8 | |

| % ≥ 4 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 7.9 | |

Readmission Rates, Mortality and Cost

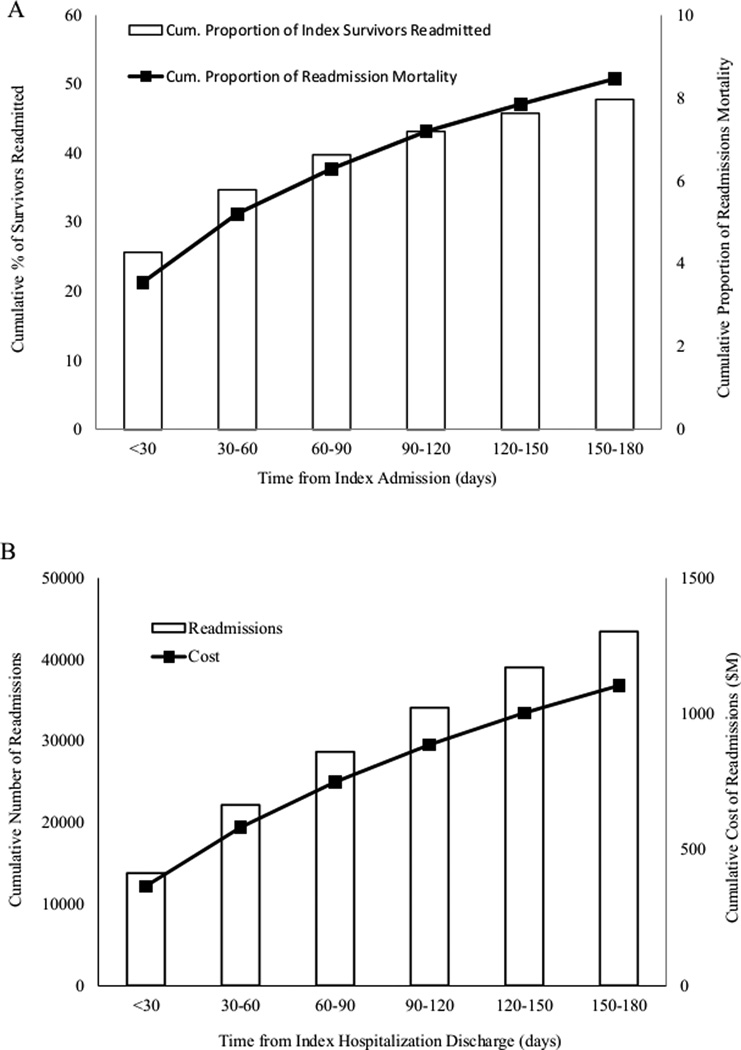

Of the 43,452 severe sepsis survivors, 26% were readmitted within 30 days of discharge and 4% died while readmitted during this time frame (Figure 2A). By 180 days, 48% of sepsis survivors had been readmitted and 8% of the original survivor cohort had died during readmission. The cumulative number of readmissions increased from 13,790 within 30 days of discharge to 43,443 admissions within 180 days of discharge which cost an estimated $366 million and $1.1 billion, respectively (Figure 2B). The mean cost of each readmission was $25,505 (standard deviation $38,765). Sepsis was the most common cause of readmission (22%) although the dataset lacked sufficient granularity to determine if these were related to unresolved sepsis or to new occurrences of sepsis.

Figure 2.

Cumulative readmissions rates and cases with associated mortality and cost. A) Approximately 26% of severe sepsis survivors were readmitted within 30 days of discharge while 48% were readmitted within 180 days. Readmissions resulted in the death of 4% of the severe sepsis survivor cohort within 30 days and of 8% of the cohort within 180 days. Black line = mortality rate of the entire severe sepsis survivor cohort attributed to readmissions. B) Severe sepsis survivors were responsible for 13,790 readmissions within 30 days of discharge and 43,443 readmissions within 180 days with a cumulative cost of $360 million and $1.1 billion, respectively. Black line = estimated cost attributed to readmissions.

Patient and Index Admission Characteristics Associated with Readmission

Multivariable logistic regression identified associations between patient/hospitalization characteristics and 30-day readmissions (Table 2). Having an age < 80 was associated with increased chance of readmissions (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.14, 1.08–1.21) while female gender was associated with a reduced chance (aOR 0.92, 0.87–0.96). Alternative age cut-offs were examined to determine if a more complex association between age and readmission risk exists. In the age < 80 population, declining age did not protect against 30 day readmissions until the threshold of 50 years of age at which point younger patients were associated with lower odds of readmission (data not shown). Black race was associated with an 18% increased odds of readmission (aOR 1.18, 1.10–1.26) compared to white race. Having Medicare or Medicaid as primary payor were both associated with increased odds of readmission (aOR 1.21, 1.13–1.30 and 1.34, 1.23–1.46; respectively). Survivor comorbidities were also associated with risk for 30-day readmission. Specifically, malignancy (aOR 1.34, 1.24–1.45), collagen vascular disease (aOR 1.30, 1.15–1.46), chronic renal failure (aOR 1.24, 1.18–1.31), chronic liver disease (aOR 1.22, 1.11–1.34), congestive heart failure (aOR 1.14, 1.08–1.19), chronic lung disease (aOR 1.12, 1.06–1.18), and diabetes mellitus (aOR 1.12, 1.07–1.17) were all associated with greater odds of readmission.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds of 30-Day All-Cause Readmissions

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Patient Demographics | |

| Medicaid | 1.34 (1.23–1.46) |

| Medicare | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) |

| Dual Medicare and Medicaid | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) |

| Black Race | 1.18 (1.10–1.26) |

| Age < 80 years | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) |

| Female Gender | 0.92 (0.87–0.96) |

| Patient Comorbidities | |

| Malignancy | 1.34 (1.24–1.45) |

| Collagen Vascular Disease | 1.30 (1.15–1.46) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) |

| Liver Disease | 1.22 (1.11–1.34) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.14 (1.08–1.19) |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.12 (1.07–1.17) |

| Index Admission Characteristics | |

| Hospital LOS above Median | 1.50 (1.43–1.57) |

| Discharge to Care Facility | 1.48 (1.40–1.56) |

| Discharge to Hospice | 0.17 (0.13–0.21) |

| Hospital Characteristics | |

| Annual Sepsis Case Volume | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) |

| Severe Sepsis Mortality Quartile | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) |

Hospital LOS greater than the survivor cohort median (10 days) was associated with a 50% greater risk of readmission (aOR 1.50, 1.43–1.57). Discharge destination also predicted readmission as survivors who were discharged to a care facility were 48% more likely to be readmitted than those who were discharged to home (aOR 1.48, 1.40–1.56). Conversely, survivors discharged to hospice care were at low risk of readmission (aOR 0.17, 0.13–0.21) and were more likely to be above age 80 (49% vs 30%, p<0.0001). For each increase in annual sepsis case volume tertile, the risk of readmission increased (aOR 1.07, 1.03–1.12). Additionally, increased hospital sepsis mortality rates were associated with more readmissions (aOR 1.04, 1.02–1.07 for each increase in quartile). Not-for-profit status and urban/rural designation were not associated with readmission risk in the multivariate model (data not shown).

During model development we included variables for acute respiratory failure, shock, acute renal failure, acute hepatic injury, central nervous system dysfunction, hematologic dysfunction, and metabolic acidosis(9). In early models, shock and acute renal failure had modest associations with readmission (data not shown); however, these associations lost significance after the addition of comorbidities to the model. The diagnosis of pneumonia was also not predictive in the multivariate model (data not shown).

Sensitivity Analysis

The Martin approach yielded a severe sepsis survivor cohort of 57,618 patients while the combination of the Martin approach and the explicit codes for severe sepsis and septic shock yielded a cohort of 69,490 patients. The 30-day readmission rate for each cohort was 24.5% and 25.0%, respectively. The multivariate logistic regression model demonstrated odds ratios similar to the primary cohort for each covariate (Supplemental Digital Content - Appendix Table 2). Only the sepsis case volume covariate lost its association with readmission in the Martin cohort, however, this association was retained in the combined cohort.

Sepsis was POA in a majority of our cases and accounted for 82.7% (n = 35,994) of the sepsis survivor cohort. Readmission trends were similar for patients with sepsis POA versus not POA (Supplemental Digital Content - Appendix Figure 1). Covariates associated with readmission and their odds ratios were similar between patients with sepsis POA and not POA (data not shown).

A Minority of Survivors Represent a Disproportionate Number of Readmissions

Of the 43,425 survivors, 9,882 (22.7%) were readmitted only once during the 180-day follow-up period while 11,025 (25.4%) were readmitted 2 or more times. Those with multiple readmissions accounted for 33,561 (77.3%) readmissions with a cumulative cost of $877.6 million (78.2% of all readmission costs).

Multivariable logistic regression was used to compare severe sepsis survivors who went on to experience one readmission to survivors who went on to experience multiple readmissions in order to determine characteristics associated with the risk of multiple readmissions (Table 3). The parsimonious model closely resembled the model which predicted any readmission in survivors (Table 2) although patient covariates such as gender, lung disease, malignancy, and liver disease; hospitalization characteristics including discharge to care facility; and hospital characteristics including sepsis case volume and sepsis mortality were not associated with multiple readmissions.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds of Requiring Multiple Readmissions within 180 days if Readmitted At Least Once

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Patient Demographics | |

| Age < 80 years | 1.39 (1.31–1.48) |

| Medicaid | 1.27 (1.13–1.42) |

| Black race | 1.17 (1.08–1.28) |

| Medicare | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) |

| Patient Comorbidities | |

| Collagen Vascular Disease | 1.21 (1.05–1.40) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) |

| Diabetes with Complications | 1.13 (1.07–1.20) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.10 (1.04–1.16) |

| Index Admission Characteristics | |

| Hospital LOS above Median | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) |

| Discharge to Hospice | 0.72 (0.53–0.98) |

Discussion

Readmission after hospitalization with severe sepsis is common and associated with significant mortality and cost. These data demonstrate that almost half of all severe sepsis survivors require readmission within 6 months of discharge with the majority of readmissions occurring within the first 30 days. If these results were extrapolated to the entire US population, severe sepsis survivors would annually experience over 91,300 readmissions within 30 days and over 171,300 readmissions within 6 months resulting in 14,200 and 30,100 in-hospital deaths and $3 billion and $9 billion in cost, respectively. The most common cause for readmission throughout the follow-up period was sepsis. Several patient characteristics were associated with the risk of 30-day readmission including age, race, gender, insurance status, and comorbidities. Longer length of stay and discharge destination to a care facility as well as higher hospital-level sepsis case volume and sepsis mortality rates were also associated with the need for readmission. Acute organ failure during the index hospitalization did not increase the risk of readmission among survivors above the risks associated with the identified comorbidities. Additionally, while the 30-day readmission rate after hospitalization for pneumonia is an important quality metric for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, these data demonstrate that early readmission is common after severe sepsis in general and is not unique to pneumonia. Finally, approximately one-quarter of severe sepsis survivors are responsible for over three-quarters of all readmissions and readmission-related costs at 6 months.

Readmissions impact patient quality of life, morbidity and mortality and now hospital reimbursement. Thus, reliable strategies to identify patients at heightened risk for readmission are important tools for clinicians, administrators, and payors. These data suggest that severe sepsis survivors are more likely to be readmitted if they are male, of black race, and have Medicare and/or Medicaid as their primary payor. These findings are consistent with readmission risk factors found in survivors of other conditions(2, 21) and may be partially explained by variations in access to care(22, 23) and health literacy(24–27). Our findings also suggest that severe sepsis survivors are less likely to be readmitted if they are over the age of 80. As increasing age, in general, leads to increased frailty, it is possible that this observed relationship has to do with palliative care-related decisions and subsequent readmission avoidance as has been reported previously (28, 29). Our observation that survivors older than 80 years are more likely to be discharged to hospice supports this hypothesis.

We speculated that acute organ failure would be associated with 30-day readmission risk due to the likelihood of diminished functional status in multi-organ failure survivors; however, in the multivariate model, acute organ failure was not predictive. One potential explanation for this observation is that the cohort of sepsis patients with the most severe organ failure are logically at greatest risk of death during the index hospitalization and thus not eligible for readmission. By design, our initial cohort was developed to investigate the risk of readmission among survivors of severe sepsis and thus represents a patient population with lower risk of death as compared to patients that died during the index hospitalization. Hence, comorbidity burden emerged as a more significant determinant for hospital readmission than acute organ failure. Severe sepsis patients commonly have substantial comorbidity burdens(9) and the comorbidities that are associated with readmission in the current study are also associated with frequent hospitalizations(30–38). Thus, many severe sepsis survivors are at risk for being “hospital dependent” patients(39) and have recently been shown to have greater need of healthcare facilities than non-sepsis survivors(40). Our observation that shock and acute renal failure were modestly associated with readmission before, but not after, the addition of comorbidities to the model suggests that comorbidity burden is the stronger determinant and is likely to be a more reliable component of readmission risk prediction tools.

While there is evidence that hospital case volume is inversely related to severe sepsis mortality(41), it appears to have a modest direct association with readmissions. A common assertion used to explain the volume-mortality relationships in critical illness is that high-volume centers possess greater expertise and resources (42, 43). As readmission rates are partly attributed to the quality of care during the index admission (3), it may be expected that index hospitalization at high-volume centers would associate with less readmissions. The opposite association that we observed could have several explanations. First, the inability to adequately control for severity of illness in ICU patients in administrative datasets introduces the possibility of confounding. However, our findings notably persisted while simultaneously controlling for age, comorbidities and the presence of acute organ failure. Second, the reduced mortality rates at high-volume centers result in a larger pool of sepsis survivors vulnerable to readmission. Inverse relationships between mortality and readmission rates have been described in other conditions(44), thus, it is possible that high-volume hospitals lead to more readmissions because they save more patients from death. To account for this, we controlled for index hospital sepsis mortality rate and, surprisingly, found that as mortality increased so, too, did readmission rates. While this may suggest that inadequate risk adjustment exists, other explanations including differences in peri-discharge care practices or differences in patient socio-economic status between high-volume and low-volume centers cannot be excluded. Finally, better-resourced, high-volume hospitals are more likely to receive inter-hospital transfers than low-volume hospitals and the distance between transferring and receiving hospitals can be substantial (45). This may lead to fragmented post-discharge care and subsequent readmission among survivors who were transferred to high-volume hospitals with severe sepsis and then return home for follow-up care.

These data demonstrate that a small proportion of severe sepsis survivors are responsible for a disproportionately large share of readmissions. The characteristics associated with increased odds of multiple readmissions were similar but not identical to those for a single readmission. Specifically, black race, Medicare/Medicaid status and comorbidities were associated with multi-readmission. We speculate that related factors including health literacy, chronic disease management skills, social support, and other factors not accessible via administrative data may be important determinants to multiple readmissions and represent significant hurdles to readmission prevention. Conversely, we hypothesize that variables such as malignancy and discharge to a care facility may not be associated with multiple readmissions because their presence may influence survival during a subsequent readmission or be associated with future decisions to pursue palliation rather than multiple readmissions.

Our study has limitations. By using administrative data, our ability to risk adjust was limited, opening the possibility to previously discussed confounding. Also, as HCUP datasets are state specific, some readmissions may have occurred in states other than where the index admission occurred and thus not included. Furthermore, an unknown proportion of our identified index readmissions may actually have been readmissions from Q3/Q4 of 2010, which we are unable to discern due to changes in patient-level identifiers between calendar years. However, our approach has precedent in other analyses of readmissions(20). The HCUP SIDs only contain information from inpatient hospitalizations, thus, outpatient data, including out-of-hospital mortality, is unavailable. This limited our ability to determine how many severe sepsis survivors were eligible for readmission during the follow up period. As such, we calculated readmission rates using the entire survivor cohort as the denominator which may result in conservatively low readmission rates. Additionally, these states’ datasets do not contain “ICU-care” codes, eliminating the ability to determine the impact of ICU requirement on readmission risk. Our observation that acute organ failure, a common reason for ICU admission, does not predict readmission in the multivariate model suggests that ICU requirement may not be associated with readmission risk but we cannot conclude this with certainty. By design, we focused only on index admissions during the first two quarters of 2011. This allowed us to determine readmission rates and risk factors, however, it limited our ability to determine annual aggregate readmission data. While seasonal variation in severe sepsis incidence and mortality(46) further limited our ability to extrapolate our aggregate data for a full year, our selection of Quarter 1 (higher incidence and mortality) and Quarter 2 (lower incidence and mortality) increased the generalizability of these data. Our data were from three states in the northeast, southeast, and southwest. As hospital readmission rates vary by geography(47), generalizability to other areas may be limited, although our findings were consistent across each state and they contain nearly 25% of the US population. Because we lacked data on peri-discharge practices including transition of care to the outpatient setting, we are unable to determine the relative roles of these variables on readmission rates. Finally, the retrospective design of the study prohibited us from establishing causality for any of the risk factors identified in the study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that 30-day and 180-day readmissions are common in severe sepsis survivors and are associated with socio-demographics, comorbidities, discharge destination, hospital LOS and index hospital characteristics. Readmissions after severe sepsis hospitalization result in substantial mortality and cost and are not exclusive to pneumonia. The majority of readmissions are generated by a minority of sepsis survivors who are of black race, Medicare/Medicaid recipients and carry a substantial comorbidity burden. Finally, hospitals with higher sepsis case volume appear to be at greater risk for sepsis readmissions. Our findings should raise the awareness of clinicians, administrators, and policy makers that as medical advances continue to improve sepsis survival, hospital readmissions will be a prevalent problem with substantial health and economic consequences. Future efforts toward readmission prediction modeling and the development of targeted interventions for high risk individuals will be critical endeavors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Gordon Rubenfeld, MD, MSc from the Interdepartmental Division of Critical Care Medicine, University of Toronto and Dr. Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS from the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy, and Sleep Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina for their critical review of the manuscript.

Funding information: Supported by Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center, Department of Defense grant number W81XWH-10-2-0057 (DWF, KNS) and the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) institute at the Medical University of South Carolina, NIH/NCATS Grant numbers KL2 TR000060 and UL1 TR000062 (AJG).

Copyright form disclosures: Dr. Goodwin received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). His institution received grant support from the NIH/NCATS (KL2 Scholars award through CTSA). Dr. Simpson’s institution received grant support from the Dept. of Defense (W81XWH-10-2-0057). Dr. Ford’s institution received grant support from the Dept. of Defense (W81XWH-10-2-0057).

Footnotes

AJG, DAR, KNS, DWF all provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and the analysis and interpretation of data. AJG and DAR authored the manuscript. DWF, KNS provided critical review of the manuscript.

Dr. Rice disclosed that he does not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.MEDPAC. Report to Congress: Promoting Greater Efficiency in Medicare. 2007

- 2.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [Erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 2011 Apr 21;364(16):1582] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashton CM, Del Junco DJ, Souchek JP, Wray NP, Mansyur CL. The Association Between the Quality of Inpatient Care and Early Readmission: A Meta-Analysis of the Evidence. Med Care. 1997;35(10):1044–1059. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2011;183(7):E391–E402. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355–363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfunter AW, LM, Steiner C. Costs for Hospital Stays in the United States, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #168. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwashyna TJ, Odden A, Rohde J, Bonham C, Kuhn L, Malani P, Chen L, Flanders S. Identifying Patients With Severe Sepsis Using Administrative Claims: Patient-Level Validation of the Angus Implementation of the International Consensus Conference Definition of Severe Sepsis. Med Care. 2012 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268ac86. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walkey AJ, Wiener RS, Ghobrial JM, Curtis LH, Benjamin EJ. Incident stroke and mortality associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306(20):2248–2254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AHRQ. Clinical Classification Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM Fact Sheet. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccsfactsheet.jsp.

- 15.Cowen ME, Dusseau DJ, Toth BG, Guisinger C, Zodet MW, Shyr Y. Casemix adjustment of managed care claims data using the clinical classification for health policy research method. Med Care. 1998;36(7):1108–1113. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson FA, Jr, Zayaruzny M, Heit JA, Fidan D, Cohen AT. Estimated annual numbers of US acute-care hospital patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(9):777–782. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA., Jr Direct medical costs of syncope-related hospitalizations in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(5):668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hines ALB, ML, Jiang J, Steiner CA. Conditions With the Largest Number of Adult Readmissions by Payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #172. 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: results of a cross-national population-based survey. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1300–1307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blustein J, Weiss LJ. Visits to specialists under Medicare: socioeconomic advantage and access to care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):153–169. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):857–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):204–211. doi: 10.1370/afm.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1278–1283. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):791–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tangeman JC, Rudra CB, Kerr CW, Grant PC. A Hospice-Hospital Partnership-Reducing Hospitalization Costs and 30-Day Readmissions among Seriously Ill Adults. J Palliat Med. 2014 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0612. (epub). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356–1361. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Rashidee A. Hospitalization of patients with heart failure: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1985 to 1995. Am Heart J. 1999;137(2):352–360. doi: 10.1053/hj.1999.v137.95495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [Erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 2008;18(4):4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foreman MG, Mannino DM, Moss M. Cirrhosis as a risk factor for sepsis and death: analysis of the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Chest. 2003;124(3):1016–1020. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang W, Chikritzhs T, Pascal R, Binns CW. Mortality rate of alcoholic liver disease and risk of hospitalization for alcoholic liver cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis and alcoholic liver failure in Australia between 1993 and 2005. Intern Med J. 2011;41(1a):34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holguin F, Folch E, Redd SC, Mannino DM. Comorbidity and mortality in COPD-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1979 to 2001. Chest. 2005;128(4):2005–2011. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selby JV, Ray GT, Zhang D, Colby CJ. Excess costs of medical care for patients with diabetes in a managed care population. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(9):1396–1402. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.9.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petri M, Genovese M. Incidence of and risk factors for hospitalizations in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(10):1559–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfe F, Caplan L, Michaud K. Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia: associations with prednisone, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(2):628–634. doi: 10.1002/art.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nietert PJ, Silverstein MD, Silver RM. Hospital admissions, length of stay, charges, and in-hospital death among patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(9):2031–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):694–697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, Escobar GJ, Iwashyna TJ. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(1):62–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walkey AJW, RS Hospital Case Volume and Outcomes among Patients Hospitalized with Severe Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(5):548–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-1967OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahn JM, Goss CH, Heagerty PJ, Kramer AA, O'Brien CR, Rubenfeld GD. Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahn JM, Branas CC, Schwab CW, Asch DA. Regionalization of medical critical care: what can we learn from the trauma experience? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(11):3085–3088. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c37b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(3):297–298. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1001882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, Moody J, Kahn JM, Asch DA. The structure of critical care transfer networks. Med Care. 2009;47(7):787–793. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318197b1f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danai PA, Sinha S, Moss M, Haber MJ, Martin GS. Seasonal variation in the epidemiology of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):410–415. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253405.17038.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodman DCF, ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Altas Report on Readmissions Among Medicare Beneficiaries. The Dartmouth Atlas. 2013 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.