Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to identify factors that are associated with poor quality of life (QOL) among cervical cancer survivors.

Methods

Patients identified through the California Cancer Registry were recruited to participate in a randomized counseling intervention. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were collected at study baseline (9–30 months post diagnosis) and subsequent to the intervention. Multivariable linear models were used to identify independent factors associated with poor baseline QOL.

Results

Non-Hispanic (N=121) and Hispanic (N=83) women aged 22 – 73 completed baseline measures. Approximately 50% of participants received radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. Compared to the US population, cervical cancer patients reported lower QOL and significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety (26% and 28% >1 SD above the general population means respectively). Among those in the lowest quartile for QOL, 63% had depression levels >1SD above the mean. In addition, treatment with radiation ± chemotherapy (p=0.014), and self-reported comorbidities predating the cancer diagnosis (p<0.001) were associated with lower QOL. Sociodemographic characteristics explained only a small portion of variance in QOL (r2=0.23). Persistent gynecologic problems, low social support, depression, somatization, less adaptive coping, comorbidities, sleep problems and low education were all independently associated with low QOL in multivariate analysis (r2=0.74).

Conclusion

We have identified key psychological and physical health factors, which contribute significantly to poor quality of life subsequent to definitive cancer treatment. The majority of these factors are amenable to supportive care interventions and should be evaluated at the time of primary treatment.

Keywords: cervical cancer, patient-reported outcomes, symptoms, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is the second most common female cancer worldwide1 and survivors often experience significant quality of life (QOL) disruptions associated with the disease and treatment, many of which persist long into survivorship.2–7 A recent analysis of health-related quality of life data among U.S. cancer survivors indicates that cancer survivors are more likely to have poor physical and mental health-related quality of life (25% and 10% respectively >1 SD above the US population mean) compared to adults with no cancer history (10% and 5% respectively). Cervical cancer survivors, and short-survival cancer survivors, report the worst mental health-related quality of life.8

Persistent sequelae include pain, bladder and bowel dysfunction,9–12 sexual dysfunction,13–16 lymphedema, and menopausal symptoms 17 as well as reproductive concerns among women of childbearing age. 5,18–21 Adverse psychological consequences are shared with women diagnosed with other gynecologic tumors, and include depression and anxiety, 22 sleep disturbance, and concentration difficulties to a greater magnitude than many other cancer patient populations. 23–25 Despite challenges inherent in this cancer survivor population, supportive interventions may assist in significantly improving quality of life, with potential to also improve stress-related biomarkers.26 This could, in turn, improve disease outcomes 27–29.

Although QOL has traditionally been examined as an outcome, it has also been considered as a predictor of survival. 4,16,30 To that end, QOL and other patient reported outcome (PRO) measures can identify cancer patients most at risk for subsequent health problems. Identification of at-risk survivor populations can guide allocation of supportive care measures during and after cancer treatment. The purpose of this study is to identify factors associated with compromised quality of life for cervical cancer survivors.

METHODS

Cervical cancer patients, identified through the California Cancer Registries (CCR), were recruited and consented to participate in a randomized psychosocial telephone counseling trial from 2008 – 2012. Thirty percent of eligible subjects enrolled in the study. Baseline PRO measures were collected subsequent to informed consent and analyzed for associations with patient characteristics.

Eligibility Criteria

Participants were eligible for this study if they had been diagnosed with Stage I, II, III or IVa disease, had completed definitive cancer treatment at least two months earlier and were free of disease, and were diagnosed not more than 30 months prior to enrollment. All patients provided informed consent consistent with federal, state and local requirements prior to enrolling in the study. Baseline questionnaires were completed by patients in English or Spanish prior to randomization to telephone counseling or usual care.

Measures

Quality of Life

The (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cervical) The FACT-Cx (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cervical) is a multidimensional, combined generic and disease-specific QOL questionnaire for cervical cancer patients. Scores range from 0 to 168 with higher scores indicating better QOL. The FACT-G (general) questionnaire (version 4) is a 27-item self-report measure which consists of four subscales (physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being),31,32 and an additional concerns subscale, which consists of fifteen items reflecting issues specific to cervical cancer. Scales can be analyzed separately, summed to produce a total FACT-Cx QOL score, or combining the Physical, Functional and Additional Concerns to produce the FACT-Trial Outcome Index (FACT-TOI).

Gynecologic Problems

The Gynecologic Problems Checklist (GPC)33,34 identifies the type and magnitude of gynecologic problems using two subscales: gynecologic problems (e.g., pelvic pain, vaginal dryness) (Cronbach’s alpha=0.72) and sexual dysfunction (e.g., pain with intercourse, loss of interest in sexual activities) (Cronbach’s alpha=0.90). Subscales are summed to yield a total score ranging from 10 to 50 with higher scores reflecting greater severity.

Emotional Distress

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (www.NIHPROMIS.org) short forms were used to measure depression and anxiety. The PROMIS emotional distress short form consists of 15 items; 8 items on depression and 7 items on anxiety. Each item in the PROMIS SF is scored from 1 to 5 points where 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, and 5=always. A high score on these PROMIS short forms connotes more emotional distress (i.e., more depression or anxiety). Standardized T-scores are calculated with mean=50 and SD=10. T-scores are normed to the general population so that a score of 50 represents the mean for the US population; a score of 60 denotes a level of depression or anxiety that is one standard deviation above the general population mean.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18), also used in this study, is a measure of psychological distress. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (always/extremely). Patients are asked to respond to each item in terms of “how they have been feeling during the past 7 days.” The BSI-18 includes subscales measuring depression, anxiety, and somatization, as well as an overall total score. Standardized scores are normed to the general population, with a mean of 50 and SD=10.2,35

Social Support

The MOS Social Support measure is a 19-item, multidimensional, self-administered survey of social support developed for the Medical Outcomes Survey of patients with chronic conditions. 36 Items reflect how often a particular source of support is available and are scored from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). The scale has been shown to have good construct validity, high reliability (alpha>0.91 for all subscales) and to be stable over time.

Coping

The Brief COPE is a 28-item questionnaire adapted from the full COPE 37 and is designed to measure ways in which people respond to stress. Factor structure is similar to the full COPE. Items ask about coping strategies used over the past month and are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1=“I didn’t do this at all” to 4 “I did this a lot”. In this study, we created subscales, which distinguish between adaptive (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and maladaptive (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68) coping.

Perceived Stress

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale assesses perceptions of stress over the past month. 38 Items reflect how frequently the patient experienced a specific feeling/state, and are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0=never to 4=very often). The PSS has good construct and convergent validity as evidenced by correlations with other measures of stress and self-reported health. Possible scores range from 0 to 40 with higher scores reflecting greater distress. 39

Medical Outcomes Sleep Scale

The 12-item self-reported sleep measure developed for the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) provides assessment of various dimensions of sleep including initiation, maintenance, respiratory problems, quantity, perceived adequacy, and somnolence. 40 A 9-item sleep problems index ranges from 0 (no problems) to 100 (severe sleep problems). Internal consistency reliability estimates for the MOS sleep scales were ≥0.63. The MOS sleep measure has been validated in the US general population and patients with neuropathic pain and found to be responsive to change over time in clinical trials. 40

Sociodemographic and Disease Characteristics

Age, ethnicity, marital status, education, and income data were collected by questionnaire at baseline. Comorbidities prior to cancer diagnosis were self-reported by patients using a 29-item checklist. Disease stage was derived from the CCR database from which patients were recruited. Treatment data were provided by patients at baseline, and validated by comparison to the CCR data.

Statistical Analyses

Summary scores were calculated for all for outcome measures with some imputation for missing values. Only 1.7% of the total number of items was missing and deemed to be missing at random. Missing items were handled according to the administration/scoring procedures in the FACT manual, prorating subscales scores under the constraints that >50% of subscale items and >80% of all items must be completed in order to create subdomain and total scores (www.facit.org). Among subjects who had completed at least 80% of all items but had some missing data, the average number of missing items ranged from 1.2 to 2.4 items for the various scales reported.

Descriptive statistics were computed for all patient characteristics and outcome measures (means and SDs for continuous variables, frequencies and percents for categorical variables). Associations between patient characteristics and outcome measures were first tested using bivariate t-tests and analysis of variance. Sociodemographic and disease characteristics that were significantly associated with at least one of the outcome measures (p<0.05) were included in multivariable analyses. Marital status and time from diagnosis to assessment were not significantly associated with any outcome measure and therefore not included. Income was correlated with education (r=0.32) and was missing for 15% of subjects, thus was not included in multivariate analyses. Adjusted associations between PRO measures and sociodemographic, tumor and treatment variables were tested using multivariable linear models (SYSTAT version 13.0). Effect sizes for PROs were calculated as the difference between subgroup means divided by the SD for the pooled group. Effects in the range of 0.33 to 0.5 have been considered to be a minimal clinically important difference. 41,42 Stepwise linear models with backward elimination and p=0.15 to remove variables were used to identify independent factors associated with QOL. Only 15 patients were treated with radiation alone, thus analyses examined the effects of radiation +/− chemotherapy compared to surgery only. Detailed stage information was not available for most patients. Because 73% of women had stage I disease and one third of these were treated with radiation therapy, stage of disease per se was not informative for multivariate analyses, and instead cancer treatment differences were examined by surgery-only versus radiation +/− chemotherapy. Variables entered in the stepwise model included sociodemographics (age, ethnicity, education), treatment, depression, anxiety, somatization, social support, gynecologic problems, coping, and sleep disturbance.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Disease Characteristics

Between October 2008 and May 2012, 204 patients were enrolled into the study and completed the baseline assessments, Sociodemographic and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Forty-one percent were Hispanic and 52% were non-Hispanic White. The mean age at study entry was 43.1 years (range 22–73) and participants were, on average, 19 months past diagnosis (range 9 – 30 months) before enrolling in the study. Most participants (73%) had stage I disease and all had completed treatment prior to participation. Forty-nine percent (n=100) were treated with surgery only while 51% (n=104) received radiation with or without chemotherapy. Compared to subjects who declined to participate, those who enrolled were significantly more likely to have early stage disease (73% vs. 61%), be of non-Hispanic white ethnicity (52% vs. 38%), and have a younger age at diagnosis (43 vs. 50 years). However, enrolled subjects included a representative proportion of Hispanics (41% compared to 40% among refusers) and did not differ significantly with respect to treatment.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Study Population

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 43.1 (range:22–73) | 9.6 |

| Age at study | 44.7 | 9.6 |

| Time from diagnosis to T1 (mo) | 19.2 | 5.4 |

| N | % | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian/Non-Hispanic | 105 | 51.5 |

| African-American | 4 | 2.0 |

| Hispanic | 83 | 40.7 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 11 | 5.4 |

| Native American | 1 | 0.5 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 31 | 15.3 |

| Married | 129 | 63.6 |

| Separated/Widowed/Divorced | 43 | 21.1 |

| Income | ||

| <$15,000 | 51 | 29.3 |

| $15,000–$35,000 | 32 | 18.4 |

| $35,000–$55,000 | 25 | 14.4 |

| ≥$55,000 | 66 | 37.9 |

| Education | ||

| < High School | 43 | 21.3 |

| High School graduate | 40 | 19.8 |

| Some college | 56 | 27.7 |

| College graduate | 33 | 16.3 |

| Graduate/professional | 30 | 14.9 |

| Stage | ||

| Stage 1 | 147 | 73.1 |

| Stage II | 28 | 13.9 |

| Stage III–IVA | 26 | 12.9 |

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery only | 100 | 49.0 |

| Radiation only | 15 | 7.4 |

| Radiation +/− Chemo | 89 | 43.6 |

| Comorbidities prior to diagnosis | ||

| None | 81 | 40.1 |

| 1 | 27 | 13.4 |

| 2 | 30 | 14.9 |

| 3+ | 64 | 31.7 |

Quality of Life and Associations with other PRO Measures

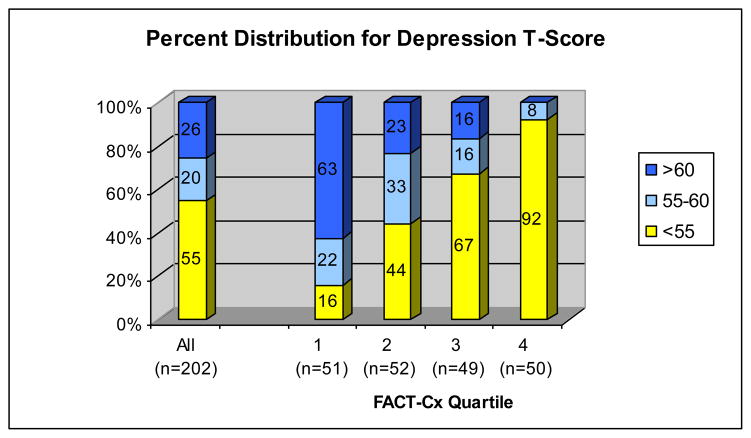

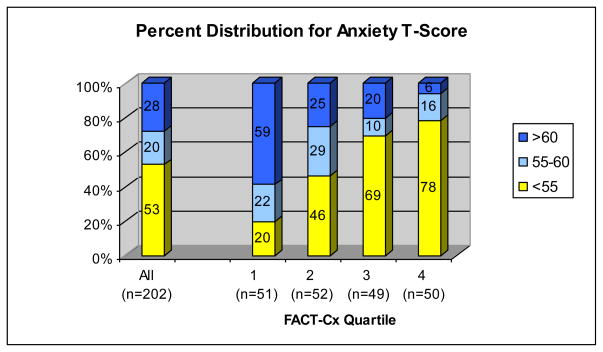

Means and standard deviations for all PROs are presented in Table 2. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate that PROMIS T-scores for depression and anxiety were >55 (0.5 SD above the mean) in 45% and 47% of patients respectively, while 26% and 28% of patients had T-scores >60, reflecting clinically significant emotional distress. Among women in the lowest QOL quartile (FACT-Cx<110), depression and anxiety T-scores >60 were reported by 63% and 59% respectively (Figures 1 and 2). In Table 3, we report both statistical significance and effect size in terms of number of standard deviations to identify characteristics that contribute to clinically important differences in QOL and other PROs.

Table 2.

Distributions of Psychological Measures

| Raw Scores | Standard Scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Range | N | Mean | SD | Range | |

| FACT-Cx | 203 | 124.7 | 24.3 | 54–165 | ||||

| FACT-Trial Outcome Index | 200 | 86.8 | 17.4 | 36–114 | ||||

| FACT-G | 203 | 80.7 | 18.4 | 27–108 | 203 | 59.8 | 10.3 | 41–100 |

| FACT-PWB | 201 | 22.7 | 5.5 | 3–18 | 201 | 74.7 | 17.8 | 24–100 |

| FACT-SWB | 203 | 19.9 | 6.0 | 3–28 | 203 | 62.1 | 17.3 | 25–100 |

| FACT-EWB | 204 | 17.7 | 4.7 | 2–24 | 204 | 65.1 | 17.8 | 18–100 |

| FACT-FWB | 204 | 20.2 | 6.4 | 1–28 | 204 | 66.7 | 18.4 | 9–100 |

| FACT-Additional Concerns (Cx) | 203 | 44.0 | 8.3 | 21–60 | ||||

| Emotional Distress-Depression TS | 203 | 17.1 | 7.5 | 8–40 | 203 | 53.3 | 9.8 | 37–81 |

| Emotional Distress-Anxiety TS | 203 | 16.1 | 7.4 | 7–35 | 203 | 53.8 | 11.4 | 36–83 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | 189 | 17.9 | 7.5 | 0–34 | ||||

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) | 204 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 0–57 | 204 | 51.7 | 11.8 | 31–80 |

| Social Support (SS-MOS) | 203 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 1.3–5 | 203 | 71.1 | 22.9 | 8–100 |

| Adaptive Coping (Brief COPE) | 202 | 41.5 | 10.3 | 16–64 | ||||

| Maladaptive Coping (Brief COPE) | 202 | 14.1 | 4.2 | 8–26 | ||||

| Gynecologic Problems Checklist (GPC) | 194 | 20.8 | 8.2 | 10–42 | ||||

| MOS Sleep Problems Index | 203 | 37.5 | 21.5 | 0–88 | ||||

Figure 1.

Percent Distribution of Emotional Distress-Depression T-Scores (PROMIS) by FACT-Cx quartiles. Fact-Cx quartiles from lowest (1) to highest (4) include scores <110, 110–128, 129–143 and >143. Overall, 26% of cervical cancer survivors report Depression T-scores >60 (>1 SD above the general population mean). Among those with the lowest QOL (FACT-Cx<110), 63% report Depression T-scores>60 and 84% report Depression T-scores >55 (>0.5 SD above the mean).

Figure 2.

Percent Distribution of Emotional Distress-Anxiety T-Scores (PROMIS) by FACT-Cx quartiles. Fact-Cx quartiles from lowest (1) to highest (4) include scores <110, 110–128, 129–143 and >143. Overall, 28% of cervical cancer survivors reported Anxiety T-scores >60 (>1 SD above the general population mean). Among women with low QOL (Fact-Cx<110), 80% reported Anxiety level >0.5 SD above the general population mean and 59% reported Anxiety >1 SD above the general population mean.

Table 3.

Adjusted Mean Scores for Psychosocial Measures by Clinical and Sociodemographic Characteristics*

| FACT-Cx | FACT-TOI | Depression T-Score | Anxiety T-Score | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 79 | 129.7 | 3.2 | 0.236 | 0.18 | 78 | 91.0 | 2.3 | 0.085 | 0.26 | 78 | 51.7 | 1.4 | 0.410 | 0.14 | 79 | 53.0 | 1.6 | 0.868 | 0.03 |

| Non-Hispanic | 119 | 1252 | 2.2 | 118 | 86.4 | 1.6 | 119 | 53.1 | 1.0 | 119 | 52.7 | 1.1 | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤40 | 76 | 127.0 | 2.9 | 0.553 | 0.12 | 75 | 88.0 | 2.1 | 0.416 | 0.17 | 75 | 53.3 | 1.3 | 0.497 | 0.09 | 76 | 53.9 | 1.5 | 0.625 | 0.11 |

| 41–50 | 70 | 125.3 | 2.8 | 69 | 87.1 | 2.0 | 70 | 51.3 | 2 | 70 | 52.0 | 1.4 | ||||||||

| >50 | 52 | 129.9 | 3.5 | 52 | 90.9 | 2.4 | 52 | 52.5 | 1.5 | 52 | 52.7 | 1.8 | ||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤ High school | 80 | 123.7 | 2.8 | 0.134 | 0.35 | 79 | 86.0 | 2.0 | 0.063 | 0.38 | 80 | 53.0 | 1.3 | 0.835 | 0.11 | 80 | 54.2 | 1.4 | 0.428 | 0.10 |

| Some College | 55 | 126.4 | 3.3 | 55 | 87.3 | 2.3 | 55 | 52.1 | 4 | 55 | 51.4 | 1.7 | ||||||||

| Col Grad/Prof | 63 | 132.1 | 3.3 | 62 | 92.6 | 2.3 | 63 | 52.0 | 1.5 | 63 | 53.0 | 1.7 | ||||||||

| Stage | ||||||||||||||||||||

| I | 145 | 122.8 | 2.0 | 0.036 | 0.38 | 144 | 86.1 | 1.4 | 0.105 | 0.29 | 146 | 53.9 | 0.9 | 0.126 | 0.30 | 146 | 54.6 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.30 |

| II–IVA | 53 | 132.1 | 3.7 | 52 | 91.2 | 2.6 | 52 | 50.9 | 1.6 | 52 | 51.1 | 1.9 | ||||||||

| Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Radiation±Chemo | 99 | 122.4 | 2.3 | 0.014 | 0.41 | 98 | 84.8 | 1.6 | 0.006 | 0.45 | 98 | 54.1 | 1.0 | 0.051 | 0.35 | 98 | 54.6 | 1.2 | 0.079 | 0.31 |

| Surgery only | 99 | 132.4 | 3.3 | 98 | 92.6 | 2.3 | 100 | 50.6 | 1.4 | 100 | 51.0 | 1.7 | ||||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 78 | 138.4 | 2.7 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 77 | 96.5 | 1.9 | <0.001 | 0.95 | 78 | 50.4 | 1.2 | 0.002 | 0.57 | 78 | 50.4 | 1.4 | 0.004 | 0.56 |

| 1–2 | 57 | 128.1 | 3.2 | 57 | 89.4 | 2.3 | 57 | 50.7 | 1.4 | 57 | 51.4 | 1.6 | ||||||||

| 3+ | 63 | 115.7 | 3.1 | 62 | 80.0 | 2.2 | 62 | 56.0 | 1.4 | 62 | 56.8 | 1.6 | ||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | D | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | |||||

| All | 198 | 125.1 | 24.1 | 0.228 | 196 | 87.2 | 17.1 | 0.246 | 197 | 53.2 | 9.8 | 0.108 | 197 | 53.7 | 11.4 | 0.109 | ||||

| Perceived Stress | BSI-GSI T-Score | Social Support-Standard Score | GPC-Total | Adaptive Coping | Maladaptive Coping | Sleep Problems (MOS) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | N | Mean | SE | p-value | effect size | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 76 | 14.4 | 1.0 | 0.002 | 0.50 | 79 | 48.7 | 1.6 | 0.110 | 0.25 | 78 | 76.2 | 3.2 | 0.220 | 0.20 | 71 | 20.0 | 1.2 | 0.756 | 0.05 | 78 | 46.2 | 1.4 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 78 | 14.4 | 0.6 | 0.247 | 0.19 | 78 | 35.3 | 2.6 | 0.444 | 0.12 |

| Non-Hispanic | 107 | 18.2 | 0.7 | 119 | 51.7 | 1.1 | 119 | 71.5 | 2.2 | 117 | 20.4 | 0.8 | 118 | 39.7 | 1.0 | 118 | 13.6 | 0.4 | 119 | 38.0 | 2.0 | ||||||||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤40 | 67 | 17.4 | 1.0 | 0.356 | 0.23 | 76 | 49.6 | 1.5 | 0.508 | 0.01 | 75 | 76.6 | 2.9 | 0.358 | 0.12 | 73 | 19.7 | 1.1 | 0.151 | 0.06 | 75 | 40.2 | 1.3 | 0.026 | 0.44 | 75 | 13.2 | 0.5 | 0.100 | 0.40 | 75 | 35.3 | 2.5 | 0.668 | 0.08 |

| 41–50 | 65 | 15.8 | 0.9 | 70 | 51.5 | 1.4 | 70 | 71.2 | 2.8 | 67 | 21.8 | 1.0 | 69 | 44.1 | 1.3 | 69 | 13.9 | 0.5 | 70 | 38.5 | 2.5 | ||||||||||||||

| >50 | 51 | 15.6 | 1.1 | 52 | 49.5 | 1.8 | 52 | 73.8 | 3.5 | 48 | 19.1 | 1.3 | 52 | 44.7 | 1.6 | 52 | 14.9 | 0.6 | 52 | 37.1 | 3.0 | ||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤ High school | 76 | 17.3 | 0.9 | 0.469 | 0.20 | 80 | 51.2 | 1.4 | 0.602 | 0.18 | 79 | 71.9 | 2.9 | 0.724 | 0.15 | 73 | 19.7 | 1.1 | 0.578 | 0.01 | 79 | 42.5 | 1.3 | 0.788 | 0.12 | 79 | 14.8 | 0.5 | 0.182 | 0.22 | 79 | 40.1 | 2.6 | 0.297 | 0.28 |

| Some College | 47 | 15.9 | 1.1 | 55 | 50.4 | 1.7 | 55 | 74.5 | 3.3 | 54 | 21.1 | 1.2 | 55 | 42.7 | 1.5 | 55 | 13.3 | 0.6 | 55 | 35.7 | 2.8 | ||||||||||||||

| Col Grad/Prof | 60 | 15.7 | 1.0 | 63 | 49.0 | 1.7 | 63 | 75.2 | 3.3 | 61 | 19.8 | 1.2 | 62 | 43.7 | 1.5 | 62 | 13.9 | 0.6 | 63 | 34.0 | 2.7 | ||||||||||||||

| Stage | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I | 134 | 18.7 | 0.6 | 0.001 | 0.65 | 145 | 52.5 | 1.0 | 0.041 | 0.39 | 144 | 68.1 | 2.0 | 0.009 | 0.51 | 139 | 20.8 | 0.7 | 0.441 | 0.15 | 143 | 41.4 | 0.9 | 0.105 | 0.31 | 143 | 14.2 | 0.4 | 0.618 | 0.10 | 144 | 41.2 | 1.8 | <0.001 | 0.73 |

| II–IVA | 49 | 13.8 | 1.2 | 53 | 47.9 | 1.9 | 53 | 79.6 | 3.7 | 49 | 19.6 | 1.4 | 53 | 44.6 | 1.7 | 53 | 13.8 | 0.7 | 53 | 25.4 | 3.3 | ||||||||||||||

| Treatment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Radiation±Chemo | 91 | 17.7 | 0.7 | 0.031 | 0.38 | 99 | 51.6 | 1.2 | 0.182 | 0.23 | 99 | 71.2 | 2.3 | 0.189 | 0.23 | 94 | 22.7 | 0.8 | 0.001 | 97 | 43.5 | 1.0 | 0.514 | 0.11 | 99 | 14.9 | 0.4 | 0.013 | 0.44 | 99 | 40.1 | 2.4 | 0.095 | 0.29 | |

| Surgery only | 92 | 14.9 | 1.1 | 99 | 48.8 | 1.7 | 98 | 76.5 | 3.3 | 94 | 17.7 | 1.2 | 0.60 | 99 | 42.4 | 1.5 | 97 | 13.1 | 0.6 | 98 | 33.8 | 2.4 | |||||||||||||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 72 | 13.4 | 0.9 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 78 | 46.1 | 1.4 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 78 | 81.0 | 2.7 | 0.002 | 0.59 | 74 | 19.1 | 1.0 | 0.314 | 0.26 | 78 | 43.8 | 1.2 | 0.063 | 0.08 | 78 | 14.0 | 0.5 | 0.432 | 0.12 | 77 | 33.7 | 2.4 | 0.124 | 0.34 |

| 1–2 | 53 | 15.5 | 1.0 | 57 | 48.9 | 1.6 | 57 | 73.0 | 3.2 | 56 | 20.2 | 1.2 | 55 | 40.5 | 1.5 | 56 | 13.5 | 0.6 | 57 | 36.8 | 2.7 | ||||||||||||||

| 3+ | 58 | 19.9 | 1.0 | 63 | 55.6 | 1.6 | 62 | 67.5 | 3.1 | 58 | 21.2 | 1.2 | 62 | 44.6 | 1.4 | 62 | 14.5 | 0.6 | 63 | 41.1 | 2.6 | ||||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | N | Mean | SD | R2 | ||||||||

| All | 183 | 17.7 | 7.5 | 0.249 | 198 | 51.4 | 11.7 | 0.164 | 197 | 71.2 | 22.7 | 0.128 | 188 | 20.5 | 8.0 | 0.119 | 196 | 41.4 | 10.4 | 0.164 | 196 | 14.0 | 4.2 | 0.137 | 197 | 36.9 | 21.4 | 0.120 | |||||||

Controlling for Age, Ethnicity, Education, Stage, Treatment and Comorbidities

Quality of Life, PROs and Associations with Cancer Treatment

There were notable cancer treatment-associated differences in QOL and PROs (Table 3). Patients who received radiation with or without chemotherapy reported significantly worse QOL (FACT-Cx: p=0.014; FACT-TOI: p=0.006) after adjusting for other covariates, compared to the surgery-only patients. Effect sizes were >0.4 SD in magnitude. Patients receiving radiation with or without chemotherapy also reported higher perceived stress (PSS, p=0.031, effect size=0.38 SD) depression (ED-Dep TS, p=0.051, effect size=0.35 SD) and anxiety (ED-Anx TS, p=0.079, effect size=0.31 SD). Gynecologic problems were also significantly more frequent in those who received radiation (GPC, p=0.001, effect size=0.60 SD) and maladaptive coping was higher (p=0.013, effect size=0.44 SD) compared to patients who had surgery only.

Quality of Life, PROs and Associations with Comorbidities

Forty percent of patients reported no major illness prior to their cancer diagnosis, while 32% reported 3 or more comorbid conditions which predated the cancer diagnosis. Among these co-morbid conditions, in greatest frequency, 21% reported back pain, 18% reported depression, 16% reported migraine headaches and 15% reported anxiety. Prior comorbid conditions were associated with significantly lower QOL (p<0.001 for both FACT-Cx and FACT-TOI), significantly higher perceived stress, depression and anxiety (p<0.01 for each), and significantly lower social support (p=0.002). Effect sizes were large, ranging from 0.56 to 0.95. Reported comorbid conditions were not associated with gynecologic problems or coping.

Multivariable Prediction of Quality of Life

Sociodemographic and patient characteristics alone explained only a small proportion of the variance in QOL with R-squared=0.23. When sociodemographics, patient characteristics and PROs were included in a multivariable linear model to explain overall QOL (Table 4); higher levels of depression, somatization, gynecologic problems, sleep disturbance, comorbidities prior to cancer diagnosis, and lower levels of adaptive coping, social support and education were independently associated with lower QOL (p<0.04 for each). Standard coefficients indicate that gynecologic problems, social support, depression, and somatization (BSI) were most strongly associated with poor QOL while coping, comorbidity, sleep disturbance and education explained smaller amounts of the variance. The adjusted squared multiple correlation was 0.74. Anxiety was not included in the model because of low tolerance and multi-collinearity. Because treatment with radiation with or without chemotherapy is associated with poor outcome for nearly every PRO, treatment was not independently associated with QOL in the multivariate model after inclusion of other PROs. Age, ethnicity, and perceived stress were not significantly associated with QOL after adjusting for other variables.

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Baseline Quality of Life (FACT-Cx) in stepwise multivariate linear regression. Dependent variable = FACT-Cx, independent variables included in stepwise model: BSI-Depression T-Score, BSI-Anxiety T-Score, BSI-Somatization T-Score, Emotional Distress-Depression T-Score, Emotional Distress-Anxiety T-Score, Social Support (MOS) Standard Score, Gynecologic Problems Checklist, Perceived Stress, Adaptive coping, Maladaptive coping, age, ethnicity, education, treatment, and comorbidity. Multiple r = 0.86. Adjusted multiple r2 = 0.74.

| Independent Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | Standard Coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynecologic Problems Checklist | −0.834 | 0.127 | −0.281 | <0.001 |

| Social Support Standard Score | 0.277 | 0.049 | 0.264 | <0.001 |

| ED-Depression T-score | −0.561 | 0.121 | −0.226 | <0.001 |

| BSI-Somatization T-score | −0.507 | 0.131 | −0.210 | <0.001 |

| Adaptive Coping | 0.365 | 0.094 | 0.153 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity (<3 vs 3+) | −5.784 | 2.180 | 0.113 | 0.009 |

| Sleep (MOS) | −0.126 | 0.059 | −0.112 | 0.035 |

| Education (≤HS vs other) | 3.882 | 1.931 | 0.080 | 0.046 |

Age, ethnicity, treatment, and Perceived Stress were not significant in the multivariate model (p>0.3 for each). Anxiety (BSI and ED) was excluded from the model because of low tolerance (<0.4).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors, in order to identify emotional, physical or social domains which could be prioritized for screening and supportive care. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the substantial symptoms of depression and anxiety in this survivor population, which exist long after cancer treatment has concluded. This magnitude of distress clearly influences and disrupts overall quality of life. For example, among women in the lowest quartile for QOL (as measured by the FACT-Cx<110), 63% reported depression and 59% reported anxiety on the PROMIS measures, with scores that exceeded the clinically meaningful threshold. 43 Notably, these scores represent a tentative threshold for moderate depression, which PROMIS has set on the Depression measure of 60, or 1 SD above the population mean. 43,44 Our results on emotional distress correspond to a similar population-based study from the Netherlands, which also reported that the cervical cancer survivor population had mental health scores worse than the reference population. 6

Patients reporting the worst QOL also reported more gynecologic problems, and less social support. The direct and buffering effects of social support among gynecologic cancer survivors has been previously illustrated, 45 and may lend further insight to inform supportive care interventions for this population. Persistent gynecologic problems, however, can be linked to cancer treatment. Not surprisingly, gynecological problems were significantly worse in patients treated with radiation with or without chemotherapy, compared to those treated with surgery only, with a moderate-to-large effect size which is both statistically and clinically significant. Treatment with radiation with or without chemotherapy also contributed to significantly poorer QOL, higher perceived stress and greater depression, with modest-to-moderate effect sizes. Use of a clinic-based gynecologic problems checklist could potentially serve as a physician-patient communication tool while simultaneously monitoring outcomes. Although it is known that radiated patients generally have poorer QOL, we did not expect that they also suffered more stress and depression. Therefore, one could anticipate that patients receiving radiation therapy could be considered an especially vulnerable subpopulation within a population who is already at greater risk of poor QOL during survivorship.

Further, patients with three or more comorbidities prior to cancer diagnosis also reported significantly worse QOL, higher perceived stress, more depression and anxiety, and lower social support. In identifying subpopulations who are likely to benefit from supportive care interventions, it appears that a brief screening of type and number of premorbid medical problems, including mood disorders, could target those at greatest need for more immediate care and attention, as well as future cancer control studies. Early screening of distress, consistent with NCCN guidelines,46 QOL and premorbid conditions could assist in patient comfort, and perhaps compliance, during and subsequent to treatment. Although our earlier pilot of a psychosocial telephone counseling intervention did promote quality of life improvement 26, we did not screen for distress. Therefore, further study of supportive care interventions to improve distress and decrease gynecologic problems in this vulnerable population appear warranted, particularly for women whose cancer treatment extends beyond surgery.

Highlights.

Cervical cancer patients experience prolonged quality of life (QOL) disruption, and are considered an especially vulnerable cancer survivor population.

Cervical cancer patients reported lower QOL and significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety than the general and survivor populations.

Psychological and physical health factors which significantly contribute to poor long-term QOL were identified as targets for potential intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Cancer Institute RO1 CA118136-01 and P30CA062203-18S3

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts to report

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 19752009, Featuring the Burden and Trends in Human Papillomavirus (HPV)Associated Cancers and HPV Vaccination Coverage Levels. Jnci-J Natl Cancer I. 2013 Feb;105(3):175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenzel L, DeAlba I, Habbal R, et al. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005 May;97(2):310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, et al. Cervical cancer survivorship in a population based sample. Gynecologic Oncology. 2009 Feb;112(2):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW, Tang J. Surviving cervical cancer: Does health-related quality of life influence survival? Gynecologic Oncology. 2010 Jul;118(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodurka DC, von Gruenigen VE. Women’s cancer survivorship: Time to gear up! Gynecologic Oncology. 2012 Mar;124(3):377–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korfage IJ, Essink-Bot ML, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse L, Kruitwagen R, van Ballegooijen M. Health-Related Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer Survivors: A Population-Based Survey. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2009 Apr 1;73(5):1501–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Distefano M, Riccardi S, Capelli G, et al. Quality of life and psychological distress in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered pre-operative chemoradiotherapy. Gynecologic Oncology. 2008 Oct;111(1):144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, et al. Mental and Physical Health-Related Quality of Life among US Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012 Nov;21(11):2108–2117. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Rothrock N, Buller RE, Sood AK, Sorosky JI. Quality of life and mood in women receiving extensive chemotherapy for gynecologic cancer. Cancer. 2000 Sep 15;89(6):1402–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Lymphedema and bladder-emptying difficulties after radical hysterectomy for early cervical cancer and among population controls. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 May-Jun;16(3):1130–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skjeldestad FE, Rannestad T. Urinary incontinence and quality of life in long-term gynecological cancer survivors: A population-based cross-sectional study. Acta Obstet Gyn Scan. 2009;88(2):192–199. doi: 10.1080/00016340802582041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover P, Clifford P, Foley M, Conway S. Uncommon and Unrecognized Causes of Nontraumatic Hip Pain in Adults: Importance of the Role of Imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 2012 May;198(5) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL. A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012 Mar;124(3):477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL. A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors (vol 124, pg 477, 2012) Gynecologic Oncology. 2012 Sep;126(3):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D. Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: A comparison to national norms. Gynecologic Oncology. 2007 Aug;106(2):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baze C, Monk BJ, Herzog TJ. The impact of cervical cancer on quality of life: A personal account. Gynecologic Oncology. 2008 May;109(2):S12–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrandina G, Mantegna G, Petrillo M, et al. Quality of life and emotional distress in early stage and locally advanced cervical cancer patients: A prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012 Mar;124(3):389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun C, Jhingran A, Gallegos J, Bodurka D, Frumovitz M, Ramondetta L. Longitudinal quality of life in medically underserved women with locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012 Mar;125:S50–S50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodurka D, Sun C, Jhingran A, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of sexual functioning and quality of life in cervical cancer survivors. Gynecologic Oncology. 2011 Mar;121(1):S81–S82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Lymphedema and bladder-emptying difficulties after radical hysterectomy for early cervical cancer and among population controls. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 May-Jun;16(3):1130–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Oct 20;23(30):7428–7436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantegna G, Petrillo M, Fuoco G, et al. Long-term prospective longitudinal evaluation of emotional distress and quality of life in cervical cancer patients who remained disease-free 2-years from diagnosis. Bmc Cancer. 2013 Mar 18;:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutgendorf S, Sood A, DeGeest K, Anderson B, Penedo F. Extending psychoneuroimmunology to the tumor microenvironment. Psycho-Oncology. 2006 Oct;15(2):S13–S13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzog TJ, Wright JD. The impact of cervical cancer on quality of life - The components and means for management. Gynecologic Oncology. 2007 Dec;107(3):572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashing-Giwa K, Rosales M, Yeung S. Assessing Distress Using Health-Related Quality of Life Measures: Applicability to Ethnic Minority Breast Cancer Survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2012 Feb;21:34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson EL, Wenzel LB, Osann K, et al. Stress, immunity, and cervical cancer: Biobehavioral outcomes of a Randomized clinical trail. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008 Apr 1;14(7):2111–2118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antoni MH. Psychosocial intervention effects on adaptation, disease course and biobehavioral processes in cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2013 Mar 15;30:S88–S98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell ND, Tarr AJ, Sheridan JF. Psychosocial stress and inflammation in cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2013 Mar 15;30:S41–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008 Aug;5(8):466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monk BJ, Pandite LN. Survival Data From a Phase II, Open-Label Study of Pazopanib or Lapatinib Monotherapy in Patients With Advanced and Recurrent Cervical Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Dec 20;29(36):4845–4845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel LB, Huang HQ, Armstrong DK, Walker J, Cella D. Validation of a FACT/GOG-abdominal discomfort (AD) subscale: A Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):754s–754s. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner LI, Wenzel L, Shaw E, Cella D. Patient-reported outcomes in phase II cancer clinical trials: lessons learned and future directions. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Nov 10;25(32):5058–5062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenzel LB, Huang HQ, Armstrong DK, Walker JL, Cella D Gynecologic Oncology G. Health-related quality of life during and after intraperitoneal versus intravenous chemotherapy for optimally debulked ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Feb 1;25(4):437–443. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruner DW, Bryan CJ, Aaronson N, et al. Issues and challenges with integrating patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials supported by the national cancer institute-sponsored clinical trials networks. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Nov 10;25(32):5051–5057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Monk BJ, Rose PG, Cella D. Quality-of-life comparisons in a randomized trial of interval secondary cytoreduction in advanced ovarian carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Aug 20;23(24):5605–5612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The Mos Social Support Survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United-States. Clar Symp. 1988:31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen S, Rabin BS. Psychologic stress, immunity, and cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998 Jan 7;90(1):3–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hays RD, Martin SA, Sesti AM, Spritzer KL. Psychometric properties of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep measure. Sleep Med. 2005 Jan;6(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 May;64(5):507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Yount SE, Riley W, Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2010 Nov;63(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, Cella D. Establishing a Common Metric for Depressive Symptoms: Linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS Depression. Psychological assessment. 2014 Feb 17; doi: 10.1037/a0035768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cella D, Lai J, Garcia SF, et al. The patient reported outcomes measurement information system-Cancer (PROMIS-Ca): Cancer-specific application of a generic fatigue measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008 May 20;26(15) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan NF, Carpenter L, Watson E, Rose PW. Cancer screening and preventative care among long-term cancer survivors in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Cancer. 2010 Mar 30;102(7):1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. NCCN.Org. 2011. NCCN Guidelines™ Version 1.2011 Panel Members Distress Management. [Google Scholar]