Abstract

In the present study, we examined whether microorganisms collaterally ingested by insects with their food activate the innate immune system to confer systemic resistance against subsequent bacterial invasion. Silkworms orally administered heat-killed Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells showed resistance against intra-hemolymph infection by P. aeruginosa. Oral administration of peptidoglycans, cell wall components of P. aeruginosa, conferred protective effects against P. aeruginosa infection, whereas oral administration of lipopolysaccharides, bacterial surface components, did not. In silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells, P. aeruginosa growth was inhibited in the hemolymph, and mRNA amounts of the antimicrobial peptides cecropin A and moricin were increased in the hemocytes and fat body. Furthermore, the amount of paralytic peptide, an insect cytokine that activates innate immune reactions, was increased in the hemolymph of silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells. These findings suggest that insects sense bacteria present in their food by peptidoglycan recognition, which activates systemic immune reactions to defend the insects against a second round of infection.

Introduction

Insects have hard exoskeletons that protect them against microbial invasion. The insect digestive tract, however, continuously comes into contact with various microorganisms present in the foods they ingest [1–4]. The intestinal epithelia recognize pathogenic microorganisms and activate an innate immune system in which the Imd and Toll pathways play central roles [5–9]. For example, in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, peptidoglycan recognition protein-LC (PGRP-LC) in the intestinal epithelial cells recognizes Gram-negative peptidoglycans and activates the Imd pathway to produce antimicrobial peptides in the gut [10–12]. The production of antimicrobial peptides and reactive oxygen species is important for the fly’s resistance against oral bacterial infection [13, 14]. In Bombyx mori silkworm larvae, oral administration of Escherichia coli induces the production of antimicrobial peptides in the gut [15]. These findings indicate that activation of immune reactions in the gut functions to defend insects against oral infection by ingested pathogenic bacteria. Oral infection also induces the production of antimicrobial peptides in tissues other than the gut in D. melanogaster [16–18]. The physiological significance of the ectopic production of antimicrobial peptides outside the gut is unclear.

Insect foods, such as plants and small-sized animals, often contain many bacteria. Insects with open wounds in such environments are thought to be at high risk for invasion by bacteria into the hemolymph. Therefore, the ability to protect themselves against the invasion of pathogenic bacteria from the food supply into the hemolymph is advantageous. In addition, insects have primed immune responses, in which a sublethal infection induces infection tolerance against a second round of infection [19–22]. We recently revealed that silkworms have a primed immune system that recognizes bacterial peptidoglycans and confers persistent infection resistance by increasing the production of antimicrobial peptides [23]. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that systemic activation of immune reactions induced by microorganisms in the silkworm food confers resistance against a second round of bacterial invasion in the hemolymph.

Silkworms eat a constant daily amount of an artificial diet, allowing for quantitative peroral administration of samples [24, 25]. The body size of the silkworms is sufficient to inject samples quantitatively and thus silkworms are suitable for evaluating infection resistance by quantitative parameters [26]. Furthermore, individual tissues, such as the gut, fat body, and hemocytes, can be isolated to measure gene expression [27]. Here, we examined whether oral administration of heat-killed bacteria confers resistance to subsequent infection in the silkworm hemolymph.

Results

Oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa induced infection resistance of silkworms against P. aeruginosa

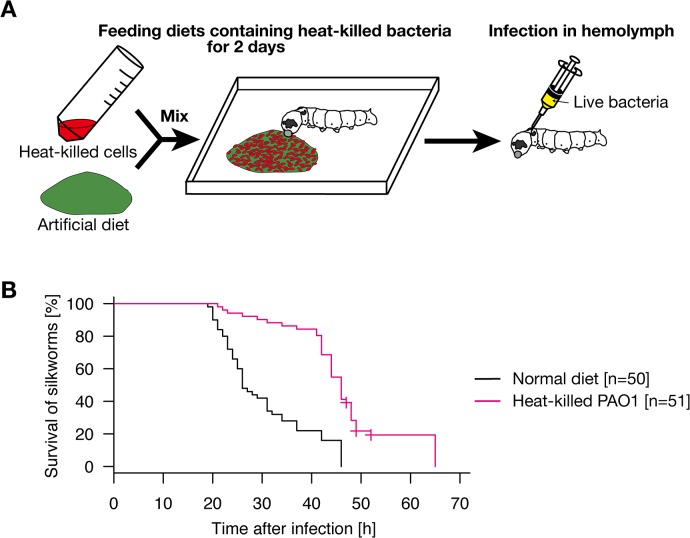

Silkworms were orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa for 2 d and then live P. aeruginosa were injected into the hemolymph (Fig 1A). The results obtained from independent experimental replicates are presented in S1 Table and S1 Fig, and the combined survival data are presented in Fig 1B. Silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa survived longer than those not administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa (Fig 1B, p = 4.59E-11). All the saline-injected silkworms survived (S1 Fig), suggesting that the observed deaths were due to P. aeruginosa infection. These findings suggest that oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa resulted in silkworm resistance against P. aeruginosa infection in the hemolymph.

Fig 1. Resistance of silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells against P. aeruginosa infection.

A. Experimental scheme of the study. Heat-killed bacterial cells were mixed with artificial diet and administered to silkworms for 2 d. Live bacteria were then injected into the silkworm hemolymph. B. Silkworms were fed a diet containing heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells (heat-killed PAO1 diet, n = 51) or a normal diet (n = 50) for 2 d and then injected with P. aeruginosa. Results from five independent trials (S1 Table, exp.1-3 and 5–6) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. Survival of silkworms fed the diet containing heat-killed P. aeruginosa was significantly higher than that of silkworms fed the normal diet (p = 4.59E-11). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S1 Fig).

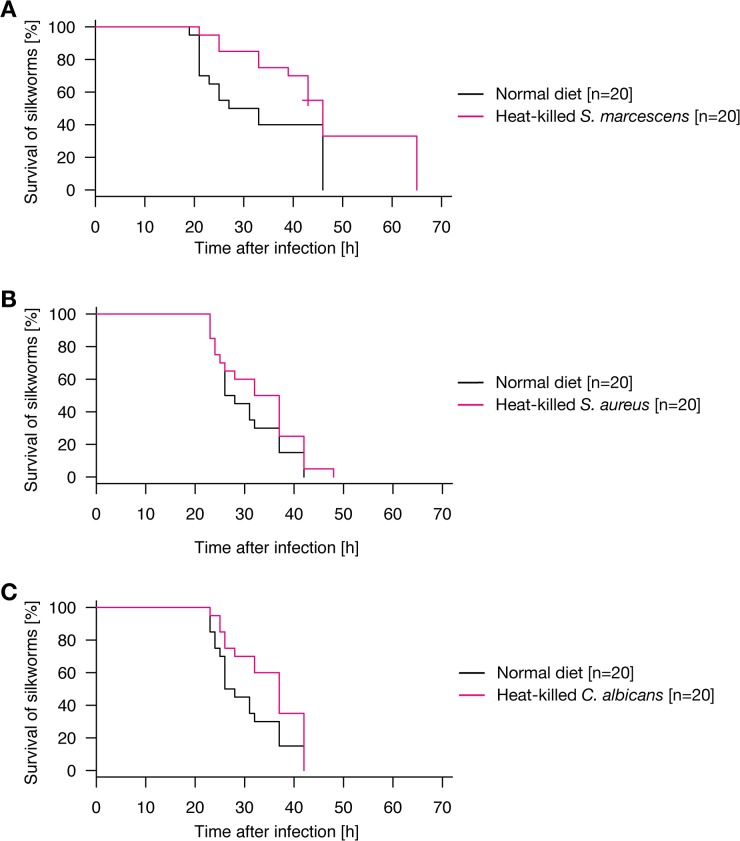

We then examined whether oral administration of heat-killed microorganisms other than P. aeruginosa confers infection resistance of silkworms against P. aeruginosa infection in the hemolymph. Silkworms that were first orally administered heat-killed Serratia marcescens, a Gram-negative pathogenic bacterium, survived longer than those not administered heat-killed S. marcescens when subsequently infected with P. aeruginosa (Fig 2A, p = 0.0219). In contrast, oral administration of heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus, a Gram-positive pathogenic bacterium, did not prolong the survival time of silkworms infected with P. aeruginosa (Fig 2B, p = 0.235). Oral administration of heat-killed Candida albicans, a pathogenic fungus, slightly prolonged the survival time of silkworms infected with P. aeruginosa (Fig 2C, p = 0.0494). These findings suggest that oral administration of heat-killed Gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi, confers resistance against intra-hemolymph infection by P. aeruginosa.

Fig 2. Resistance of silkworms orally administered with heat-killed cells of various microorganisms against P. aeruginosa infection.

A. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (n = 20) or a diet containing heat-killed cells of S. marcescens (n = 20) for 2 d, and then infected with P. aeruginosa in hemolymph. Results from two independent trials (S1 Table, exp. 3–4) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. Survival of silkworms fed a diet containing heat-killed S. marcescens cells was significantly higher than that of silkworms fed a normal diet (p = 0.0219). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S1 Fig). B. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (n = 20) or a diet containing heat-killed S. aureus cells (n = 20) for 2 d, and then injected with P. aeruginosa. Results from two independent trials (S1 Table, exp. 5–6) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. Survival of silkworms fed a diet containing heat-killed S. aureus cells was not significantly different from that of silkworms fed a normal diet (p = 0.235). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S1 Fig). C. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (n = 20) or a diet containing heat-killed C. albicans cells (n = 20) for 2 d, and then injected with P. aeruginosa. Results from two independent trials (S1 Table, exp. 5–6) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. Survival of silkworms fed a diet containing heat-killed C. albicans cells was significantly higher than that of silkworms fed a normal diet (p = 0.0494). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S1 Fig).

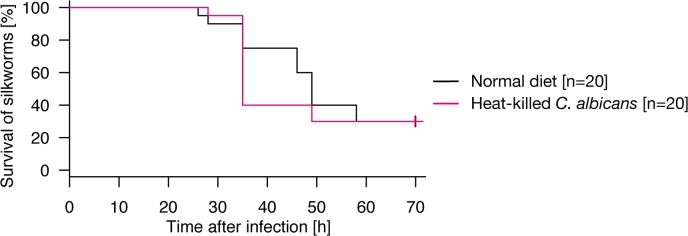

We further examined whether the protective effect of heat-killed fungal cells are observed against fungal infection. Oral administration of heat-killed C. albicans did not prolong survival time when the hemolymph was infected with C. albicans (Fig 3, p = 0.995). This result suggests that oral administration of heat-killed fungi is not effective against subsequent intra-hemolymph fungal infection.

Fig 3. Resistance of silkworms orally administered heat-killed fungi against fungal infection.

Silkworms were fed a normal diet (n = 20) or a diet containing heat-killed C. albicans cells (n = 20) for 2 d, and then injected with C. albicans. Results from two independent trials (S1 Table, exp. 7–8) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. Survival of silkworms fed the diet containing heat-killed C. albicans cells was comparable to that of silkworms fed the normal diet (p = 0.995). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S1 Fig).

Oral administration of P. aeruginosa peptidoglycans confers infection resistance against P. aeruginosa

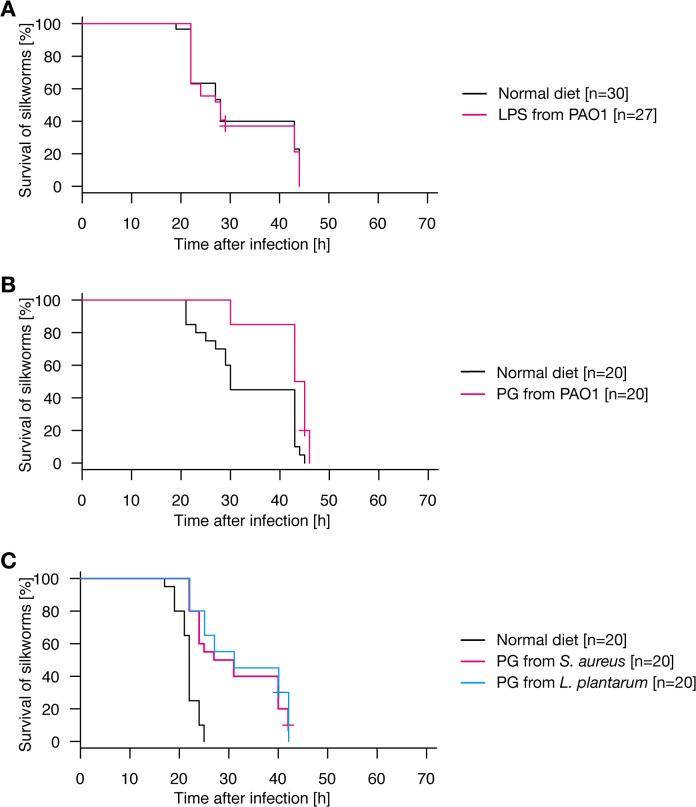

Lipopolysaccharides are abundantly present in Gram-negative cell walls, and peptidoglycans are present in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial surfaces. These molecules activate innate immune responses. Therefore, we examined whether oral administration of lipopolysaccharides or peptidoglycans confers resistance of silkworms against intra-hemolymph infection by P. aeruginosa. Silkworms orally administered P. aeruginosa lipopolysaccharides did not survive longer than silkworms not administered lipopolysaccharides when the hemolymph was infected with P. aeruginosa (Fig 4A, p = 0.893). In contrast, silkworms orally administered P. aeruginosa peptidoglycans survived significantly longer than silkworms not administered P. aeruginosa peptidoglycans when the hemolymph was infected with P. aeruginosa (Fig 4B, p = 1.76E-04). These findings suggest that peptidoglycans were responsible for the activity of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells to confer resistance to the silkworms against P. aeruginosa intra-hemolymph infection.

Fig 4. Oral administration of P. aeruginosa peptidoglycan leads to infection resistance of silkworms against P. aeruginosa.

A. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (n = 30) or a diet containing P. aeruginosa lipopolysaccharides (n = 27) for 2 d and then injected with P. aeruginosa. Results from three independent trials (S2 Table, exp. 1–3) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. Survival of silkworms fed the normal diet did not differ significantly from that of silkworms fed the diet containing lipopolysaccharides (p = 0.893). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S2 Fig). B. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (n = 20) or a diet containing P. aeruginosa peptidoglycans (n = 20) for 2 d, and then injected with P. aeruginosa. Results from two independent trials (S2 Table, exp. 4–5) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figure. The survival of silkworms fed the diet containing P. aeruginosa peptidoglycans was significantly longer than that of silkworms fed the normal diet (p = 1.76E-04). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S2 Fig). C. Silkworms were administered a normal diet (n = 20), diet containing S. aureus peptidoglycans (n = 20), or diet containing L. plantarum peptidoglycans (n = 20) for 2 d, and then injected with P. aeruginosa. Results from two independent trials (S2 Table, exp. 6–7) were combined into a single analysis. The combined survival curve is shown in the figures. Survival of silkworms fed a diet containing S. aureus or L. plantarum peptidoglycans was significantly longer than that of silkworms fed a normal diet (p = 5.62E-06 or 3.37E-07). None of the mock-infected silkworms died (S2 Fig).

Because oral administration of heat-killed S. aureus cells did not protect silkworms from P. aeruginosa infection, we examined whether the protecting effects are different between Gram-positive and Gram-negative peptidoglycans. We extracted peptidoglycans from S. aureus and Lactobacillus plantarum. S. aureus has a Gram-positive type peptidoglycan and L. plantarum has a DAP-type peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid [28, 29]. Oral administration of both S. aureus peptidoglycan and L. plantarum peptidoglycan prolonged silkworm survival time when the hemolymph was infected with P. aeruginosa (Fig 4C, p = 5.62E-06 and 3.37E-07, respectively). The effects of S. aureus peptidoglycan and L. plantarum peptidoglycan were comparable (p = 0.944). These findings suggest that orally ingested peptidoglycans from S. aureus and L. plantarum confer infection resistance against P. aeruginosa infection in silkworm hemolymph.

Induction of antimicrobial activity in the silkworm hemolymph by oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells

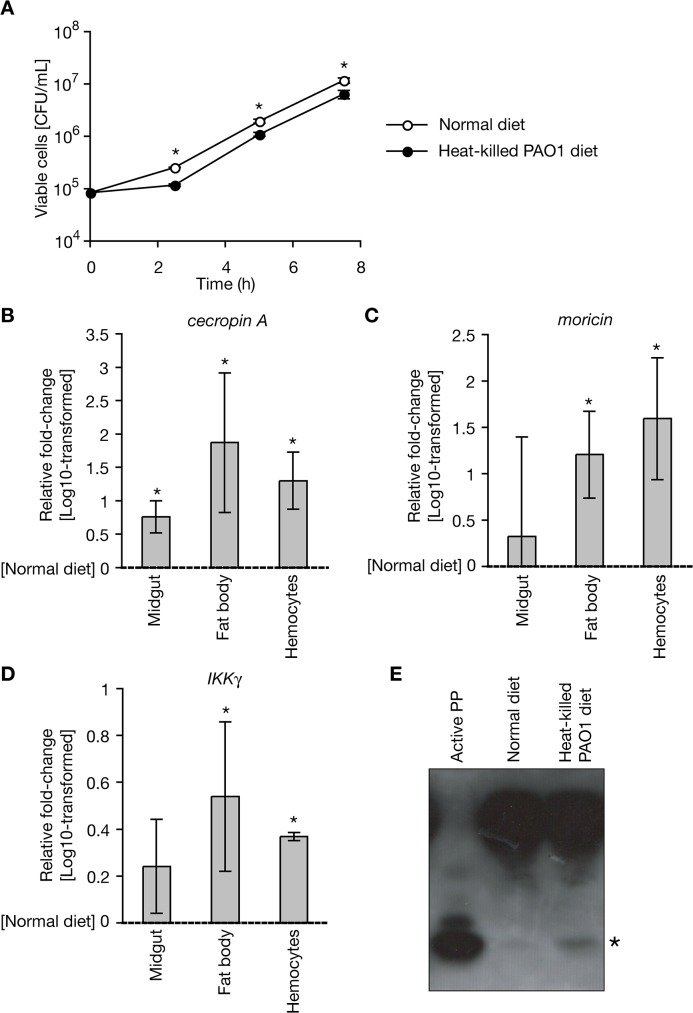

We then examined the molecular mechanism underlying the protective effect of oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells against P. aeruginosa intra-hemolymph infection. We hypothesized that antimicrobial activity was induced against P. aeruginosa in the silkworm hemolymph. We collected hemolymph samples from silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells, and cultured living P. aeruginosa cells in the hemolymph samples. Compared to the control sample, the growth of P. aeruginosa in the hemolymph from silkworms administered the heat-killed P. aeruginosa was inhibited (Fig 5A). This finding indicates that antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa was induced in the silkworm hemolymph by oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa.

Fig 5. Activation of systemic immunity in silkworms by oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa.

A. Hemolymph samples were collected from fifth instar silkworms (n = 3) fed a diet containing heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells for 23 h, and living P. aeruginosa was inoculated into the hemolymph and incubated at 37°C. After incubation, samples were diluted and spread on agar plates for measurement of viable cell numbers. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Asterisk indicates p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). A representative result from two independent experiments is shown. B, C, D. Total RNAs were extracted from the midgut, fat body, or hemocytes of fifth instar silkworms fed diet containing heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells for 2 d. The amounts of cecropin A, moricin, and IKKγ mRNA in the extracted RNA fractions were then measured. Each RNA amount was normalized by the mRNA amount of elongation factor-2. Values in the silkworms fed with heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells relative to that in the silkworms fed with normal diet were log-transformed, and the mean values ± SD from three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with silkworms on the normal diet (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test). The log-transformed values were used in the statistical analysis because they exhibited higher normality than the non-transformed values. E. Hemolymph samples were collected from silkworms (n = 4) fed a normal diet or diet containing heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells. The samples, containing 28 μg protein, were electrophoresed using 16.5% tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins in the gels were then transferred to a membrane and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-PP antibody. Asterisk indicates the active-form of PP. A representative result from two independent experiments is shown.

Expression of immune-associated genes by oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa

Because silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa exhibited infection tolerance against P. aeruginosa and antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa was induced in the hemolymph of these silkworms, we hypothesized that heat-killed P. aeruginosa systemically activates silkworm immunity, resulting in the transcriptional activation of genes coding antimicrobial peptides. We measured the amounts of cecropin A and moricin mRNA in the midgut, fat body, and hemocytes of silkworms fed a diet with or without heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells. In the fat body and hemocytes, the amounts of cecropin A and moricin mRNA were greater in silkworms fed the diet containing the heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells than in silkworms fed the normal diet (Fig 5B and 5C). The amount of cecropin A mRNA was also increased in the midgut, whereas that of moricin was not (Fig 5B and 5C). These findings suggest that systemic activation of antimicrobial peptide expression occurs in silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells.

In insects, the expression of antimicrobial peptides is regulated by nuclear factor-kB, which is regulated by the I kappa B kinase (IKK) complex in the IMD pathway [30]. The expression of IKKγ, a component of the IKK complex, was upregulated in the fat body and hemocytes of silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells (Fig 5D). A recent report demonstrated that the insect cytokine paralytic peptide (PP) is activated by the injection of peptidoglycans, leading to the systemic activation of innate immune responses [31]. The amount of activated PP was increased in the hemolymph of silkworms orally administered heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells (Fig 5E). These findings suggest that oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells activates the PP and IMD pathways, and results in the systemic expression of antimicrobial peptides.

Discussion

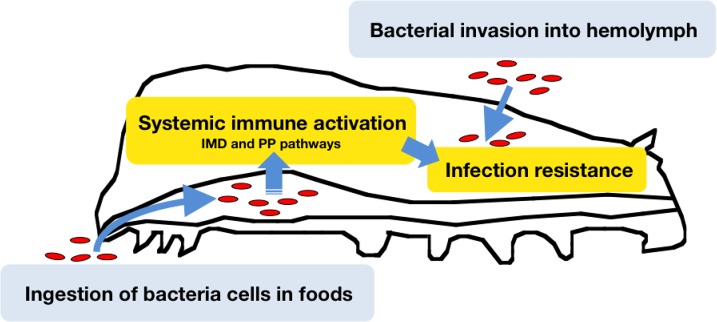

The findings of the present study demonstrated that oral administration of heat-killed microbes, conferred resistance of silkworms against P. aeruginosa infection in the hemolymph. Further, oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells induced the expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in the midgut, fat body, and hemocytes of silkworms. In addition, IKKγ and PP, which activate the expression of antimicrobial peptides, were increased by oral administration of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells, suggesting that the silkworms innate immune system responds to orally-ingested microorganisms, resulting in resistance against subsequent microbial infection in the hemolymph (Fig 6). This study is the first to demonstrate the physiologic significance of systemic immune activation by ingested bacteria in insects as a primed immune response.

Fig 6. Model of primed immune responses triggered by ingestion of bacteria.

Silkworms ingest bacteria with their food. The ingested bacteria activate systemic immune responses in the gut, which leads to tolerance against bacterial invasion into the hemolymph.

The present study revealed that oral administrations of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells, heat-killed S. marcescens cells, and heat-killed C. albicans cells had significant effects to protect silkworms against subsequent infection by P. aeruginosa. In contrast, heat-killed S. aureus cells did not protect silkworms against P. aeruginosa infection. This indicates that the primed immune response protecting silkworms against P. aeruginosa infection are triggered by ingestion of Gram-negative bacteria cells or fungal cells, but not by ingestion of Gram-positive bacteria. These findings are also consistent with our previous observation that injecting heat-killed S. aureus cells into silkworm hemolymph did not confer a protective effect against E. coli infection [23]. S. marcescens and P. aeruginosa infect various insects in natural environments [18, 32], whereas S. aureus is not a natural insect pathogen (the Ecological Database of the World’s Insect Pathogens) [33]. Insects may possess a sensitive immune-activation system for these naturally pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria.

This study demonstrated that oral administrations of peptidoglycans from P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and L. plantarum showed the protecting effects against P. aeruginosa infection. We did not detect difference between the effect of peptidoglycans from S. aureus and L. plantarum, which contain Lys-type peptidoglycans and DAP-type peptidoglycans, respectively (p = 0.944). This indicates that silkworm immune system can recognize both the Lys-type and DAP- type peptidoglycans. Because the heat-killed S. aureus cells did not show the protecting effect, the S. aureus cellular peptidoglycan may have a different conformation from that of the purified peptidoglycan, which escapes the recognition by the silkworm immune system. Further investigations are necessary to answer why the silkworm immune system recognizes orally ingested heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells, but not the heat-killed S. aureus cells.

Both PP and IKKγ are suggested to be involved in the mechanism underlying immune activation by orally ingested heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells. Because PP does not increase the amount of IKKγ [31] and the activation of PP occurs within minutes by reactive oxygen species [34], the PP and IKKγ pathways may be independently activated by gut epithelial cells after the recognition of heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells to activate systemic production of antimicrobial peptides. Previous studies reported that hemocytes are involved in the primed immune responses in lower organisms [22]. In the woodlouse Porcellio scaber, an increasing number of phagocytosing hemocytes are involved in the primed immune response [35]. In mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae, the number of granulocytes increases to protect against parasite infection [20]. Further studies are needed to reveal the molecular mechanisms of microorganism recognition by gut epithelial cells and the involvement of hemocytes to lead systemic activation of immune reactions as a primed immunity.

Animals, from arthropods to humans, ingest many bacterial or fungal cells collaterally with their food sources. Humans, in addition, have developed fermentation techniques to make fermented food. Several insect species prefer ingesting microbes, such as the leaf-cutting ant, which cultivates fungus on plant leaves. The present study demonstrates a physiological significance of microbes present in animal food sources such that they activate immune systems to defend animals against potential microbial infection.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria or fungi

P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain was cultured in Luria-Bertani medium (1% Tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) at 30°C. S. aureus NCTC8325-4 was cultured at 37°C in Tryptic Soy Broth medium (BD Bioscience). S. marcescens 2170 strain was cultured at 30°C in Brain-Heart Infusion medium (BD Bioscience). C. albicans ATCC10231 was cultured at 37°C in YPD medium. L. plantarum JCM1057 (Riken BRC, National BioResource Project of the MEXT, Japan) was cultured in MRS medium at 30°C.

Insects

Eggs of Bombyx mori silkworms were purchased from Ehime-Sanshu (Ehime, Japan). The hatched silkworm larvae were fed an artificial diet containing antibiotics (Silkmate 2S, Nihon Nosan Corporation, Yokohama, Japan) up to the fifth instar larval stage. After the fifth instar stage, the silkworms were fed an antibiotic-free diet (Katakura Industries, Tokyo, Japan) [36].

Heat treatment of bacteria or fungi

The overnight culture of each bacterium or fungus was centrifuged (12,000 g, 4°C, 10 min), and the pellets were re-suspended in saline. The suspensions were autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min. Autoclaved samples were centrifuged (12,000 g, 4°C, 10 min) and the supernatants were removed. The samples were stored at -20°C.

Oral administration of heat-killed bacteria to silkworms

A fifth instar silkworm larva consumes ~2.3 g of artificial diet over 2 d. An artificial diet containing heat-killed bacteria or fungi was prepared by mixing 23 g of antibiotic-free artificial diet and heat-killed bacterial or fungal suspension from overnight cultures. The actual volume of the culture for each experiment is listed in S1 Table. The artificial diet with or without heat-killed bacteria cells was fed to fifth instar silkworms from day 1 to day 3 of the fifth instar larval stage.

Intra-hemolymph infection of silkworms

After feeding on the artificial diets for 2 d, silkworms were injected into the hemolymph with living bacteria cells (50 μL) using a 1-mL syringe equipped with a 27-gauge needle (Terumo) [37]. Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and C. albicans were diluted 103-fold, 30-fold, and 10-fold, respectively, and used for infection. The silkworms were then incubated in a plastic cage at 27°C and survival was assessed.

Extraction of lipopolysaccharides and peptidoglycans from P. aeruginosa

Lipopolysaccharides were extracted by the hot-phenol method [38]. Fourteen liters of P. aeruginosa culture was centrifuged (12,000 g, 10 min, 4°C) and washed with saline. The pellets were re-suspended in acetone, centrifuged (16,200 g, 10 min, 4°C), and dried. The dried sample was suspended in 65°C water and sonicated. An equal volume of 90% phenol (preheated to 65°C) was added and incubated at 65°C for 30 min. The centrifuged supernatant was mixed again with equal volume of 90% phenol (preheated to 65°C) and incubated for 30 min. The centrifuged sample was dialyzed against water, frozen at -20°C, and dried using a freeze dryer. The sample was suspended in 0.5 M NaCl and mixed with 1.5 volume of 2% Cetavlon (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide)/0.5 M NaCl. The centrifuged supernatant was frozen at -20°C and dried using a freeze dryer. The sample was suspended in 0.5 M NaCl and mixed with 10 volumes of ethanol and stirred at 4°C for 2 h. The sample was centrifuged (16,200 g, 10 min, 4°C) and the precipitate was suspended in water. The sample was dialyzed against water, frozen at -20°C, dried using a freeze dryer, resulting in lipopolysaccharide fraction. We measured its dry weight to quantify the lipopolysaccharide sample. The sample was suspended in saline before use.

Peptidoglycans were extracted as described previously [39]. Two liters of P. aeruginosa culture was centrifuged (12,000 g, 10 min, 4°C) and washed with saline. The pellets were re-suspended in water and autoclaved for 15 min at 121°C. Samples were washed with water and acetone three times each, and then dried at room temperature. The dried powder was suspended in water and fractured using a French press (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fractured sample was washed three times with water, then dried at room temperature, and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline. The suspension was treated overnight with DNaseI (Takara) and RNaseA (Sigma) at 37°C, followed by treatment with trypsin (Nacalai) at 37°C overnight. The sample was then washed three times with water, suspended in 5% trichloroacetate, and incubated overnight at 27°C. After 1 h at 4°C, the sample was centrifuged (16,200 g, 4°C, 10 min) and the pellet was washed three times with water and acetone, dried at room temperature, and stored at -20°C. We measured its dry weight to quantify the peptidoglycan sample. The prepared peptidoglycans sample was suspended in phosphate-buffered saline and treated by sonication before use.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Silkworms on day 1 of the fifth instar stage were fed an artificial diet containing heat-killed P. aeruginosa cells and incubated for 2 d at 27°C. Total RNA from hemocytes, midgut, and fat body of the silkworms was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After digestion of the contaminated genomic DNA by RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega), the RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using TaqMan reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed using oligonucleotide primers (Table 1), cDNAs as a template, and FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche).

Table 1. Primers used in this study.

| Target | Primer | Sequence (5'-3') |

|---|---|---|

| elongation factor 2 | F-ef2 | GTGCGAGAGCCGGAGAGAC |

| R-ef2 | CGAAGAACATAGAGATGGCCG | |

| cecropin A | F-cecA | TTGAGCTTCGTCTTCGCGTT |

| R-cecA | TTGCGTCCCACTTTCTCAATT | |

| moricin | F-mor | CCGCTCCAGCAAAAATACCT |

| R-mor | TTGAAAACATCGTTGGCTGT | |

| IKKγ | F-IKKg | GACGACGACACCATGAA |

| R-IKKg | AACTATATGCTCCAGGG |

Detection of activated PP in the silkworm hemolymph

Silkworms were fed an artificial diet with or without heat-killed bacteria. Prolegs were dissected to collect the hemolymph. Immediately after hemolymph collection, the hemolymph samples were boiled for 5 min. The supernatant of the boiled samples was centrifuged (10,000 g, 5 min) and analyzed by Western blotting. Synthesized active-form PP was used as a control [34]. Protein samples were electrophoresed using 16.5% tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The membrane was hybridized with 1:6000 diluted anti-PP antibody suspended in a blocking solution, and then reacted with 1:5000 diluted anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G from donkey linked with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences). The membrane was treated with Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and luminescence signals were detected on autoradiography film (Hyperfilm-ECL, Amersham Biosciences, UK).

Statistical analysis

A statistical summary of all infection experiments in this study is shown in S1 and S2 Tables. The replicates for each experiment were then combined into a single analysis. To test the difference in survival curves, we performed log-rank tests using R ver.2.15.3 on Mac OS X. The package “survival” was used to perform a log-rank test. We applied Bonferroni’s correction to test the significance level of the differences of multiple samples. To test the difference in mean values, we performed Student’s t-test using Microsoft Excel 2011 for Mac OS.

Supporting Information

Silkworms were fed a normal diet or a diet containing heat-killed microbial cells for 2 d, and then injected with living microbial cells. Experimental conditions and statistical analysis for each experiment are presented in S1 Table.

(TIF)

Silkworms were fed a normal diet or a diet containing lipopolysaccharide or peptidoglycan for 2 d, and then injected with living P. aeruginosa cells. Experimental conditions and statistical analysis for each experiment are presented in S2 Table.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 23249009, 24590519, 25117507, 26670025 and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research Fellowships for Young Scientists Grant 25-8664 (to A.M.). This study was supported in part by the Genome Pharmaceutical Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Macpherson AJ, Harris NL. Interactions between commensal intestinal bacteria and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(6):478–85. Epub 2004/06/03. 10.1038/nri1373 nri1373 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sansonetti PJ. War and peace at mucosal surfaces. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(12):953–64. Epub 2004/12/02. doi: nri1499 [pii] 10.1038/nri1499 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macdonald TT, Monteleone G. Immunity, inflammation, and allergy in the gut. Science. 2005;307(5717):1920–5. Epub 2005/03/26. doi: 307/5717/1920 [pii] 10.1126/science.1106442 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292(5519):1115–8. Epub 2001/05/16. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aggarwal K, Rus F, Vriesema-Magnuson C, Erturk-Hasdemir D, Paquette N, Silverman N. Rudra interrupts receptor signaling complexes to negatively regulate the IMD pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(8):e1000120 Epub 2008/08/09. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743. Epub 2007/01/05. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Gregorio E, Han SJ, Lee WJ, Baek MJ, Osaki T, Kawabata S, et al. An immune-responsive Serpin regulates the melanization cascade in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2002;3(4):581–92. Epub 2002/11/01. doi: S1534580702002678 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemaitre B, Kromer-Metzger E, Michaut L, Nicolas E, Meister M, Georgel P, et al. A recessive mutation, immune deficiency (imd), defines two distinct control pathways in the Drosophila host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(21):9465–9. Epub 1995/10/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86(6):973–83. Epub 1996/09/20. doi: S0092-8674(00)80172-5 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zaidman-Remy A, Herve M, Poidevin M, Pili-Floury S, Kim MS, Blanot D, et al. The Drosophila amidase PGRP-LB modulates the immune response to bacterial infection. Immunity. 2006;24(4):463–73. Epub 2006/04/19. doi: S1074-7613(06)00177-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaneko T, Goldman WE, Mellroth P, Steiner H, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, et al. Monomeric and polymeric gram-negative peptidoglycan but not purified LPS stimulate the Drosophila IMD pathway. Immunity. 2004;20(5):637–49. Epub 2004/05/15. doi: S1074761304001049 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leulier F, Parquet C, Pili-Floury S, Ryu JH, Caroff M, Lee WJ, et al. The Drosophila immune system detects bacteria through specific peptidoglycan recognition. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(5):478–84. Epub 2003/04/15. 10.1038/ni922 ni922 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ha EM, Lee KA, Park SH, Kim SH, Nam HJ, Lee HY, et al. Regulation of DUOX by the Galphaq-phospholipase Cbeta-Ca2+ pathway in Drosophila gut immunity. Dev Cell. 2009;16(3):386–97. Epub 2009/03/18. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.015 S1534-5807(09)00029-X [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ha EM, Lee KA, Seo YY, Kim SH, Lim JH, Oh BH, et al. Coordination of multiple dual oxidase-regulatory pathways in responses to commensal and infectious microbes in drosophila gut. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(9):949–57. Epub 2009/08/12. 10.1038/ni.1765ni.1765 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu S, Zhang X, Chen X, Cao P, Beerntsen BT, Ling E. BmToll9, an Arthropod conservative Toll, is likely involved in the local gut immune response in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34(2):93–6. Epub 2009/09/03. 10.1016/j.dci.2009.08.010 S0145-305X(09)00177-3 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Basset A, Khush RS, Braun A, Gardan L, Boccard F, Hoffmann JA, et al. The phytopathogenic bacteria Erwinia carotovora infects Drosophila and activates an immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(7):3376–81. Epub 2000/03/22. 10.1073/pnas.070357597 070357597 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tzou P, Ohresser S, Ferrandon D, Capovilla M, Reichhart JM, Lemaitre B, et al. Tissue-specific inducible expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Drosophila surface epithelia. Immunity. 2000;13(5):737–48. Epub 2000/12/15. doi: S1074-7613(00)00072-8 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vodovar N, Vinals M, Liehl P, Basset A, Degrouard J, Spellman P, et al. Drosophila host defense after oral infection by an entomopathogenic Pseudomonas species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(32):11414–9. Epub 2005/08/03. doi: 0502240102 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0502240102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sadd BM, Schmid-Hempel P. Insect immunity shows specificity in protection upon secondary pathogen exposure. Curr Biol. 2006;16(12):1206–10. Epub 2006/06/20. doi: S0960-9822(06)01694-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.047 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science. 2010;329(5997):1353–5. Epub 2010/09/11. 10.1126/science.1190689 329/5997/1353 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pham LN, Dionne MS, Shirasu-Hiza M, Schneider DS. A specific primed immune response in Drosophila is dependent on phagocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(3):e26. Epub 2007/03/14. doi: 06-PLPA-RA-0469R2 [pii] 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun JC, Ugolini S, Vivier E. Immunological memory within the innate immune system. EMBO J. 2014;33(12):1295–303. Epub 2014/03/29. 10.1002/embj.201387651 embj.201387651 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyashita A, Kizaki H, Kawasaki K, Sekimizu K, Kaito C. Primed immune responses to Gram-negative peptidoglycans confer infection resistance in silkworms. J Biol Chem. 2014. Epub 2014/04/08. doi: M113.525139 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M113.525139 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Hamamoto H, Kurokawa K, Kaito C, Kamura K, Manitra Razanajatovo I, Kusuhara H, et al. Quantitative evaluation of the therapeutic effects of antibiotics using silkworms infected with human pathogenic microorganisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):774–9. Epub 2004/02/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaito C, Sekimizu K. A silkworm model of pathogenic bacterial infection. Drug Discov Ther. 2007;1(2):89–93. Epub 2007/10/01. doi: 56 [pii]. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miyazaki S, Matsumoto Y, Sekimizu K, Kaito C. Evaluation of Staphylococcus aureus virulence factors using a silkworm model. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;326(2):116–24. Epub 2011/11/19. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02439.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamamoto H, Tonoike A, Narushima K, Horie R, Sekimizu K. Silkworm as a model animal to evaluate drug candidate toxicity and metabolism. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2009;149(3):334–9. Epub 2008/09/23. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.08.008 S1532-0456(08)00163-4 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takehana A, Katsuyama T, Yano T, Oshima Y, Takada H, Aigaki T, et al. Overexpression of a pattern-recognition receptor, peptidoglycan-recognition protein-LE, activates imd/relish-mediated antibacterial defense and the prophenoloxidase cascade in Drosophila larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(21):13705–10. Epub 2002/10/03. 10.1073/pnas.212301199 212301199 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurata S. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins in Drosophila immunity. Dev Comp Immunol. 2013. Epub 2013/06/26. doi: S0145-305X(13)00169-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.dci.2013.06.006 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Lemaitre B. The road to Toll. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(7):521–7. Epub 2004/07/02. 10.1038/nri1390nri1390 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishii K, Hamamoto H, Kamimura M, Nakamura Y, Noda H, Imamura K, et al. Insect cytokine paralytic peptide (PP) induces cellular and humoral immune responses in the silkworm Bombyx mori. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(37):28635–42. Epub 2010/07/14. 10.1074/jbc.M110.138446 M110.138446 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grimont PA, Grimont F. The genus Serratia. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1978;32:221–48. Epub 1978/01/01. 10.1146/annurev.mi.32.100178.001253 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braxton SM, Onstad DW, Dockter DE, Giordano R, Larsson R, Humber RA. Description and analysis of two internet-based databases of insect pathogens: EDWIP and VIDIL. J Invertebr Pathol. 2003;83(3):185–95. Epub 2003/07/25. doi: S0022201103000892 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ishii K, Hamamoto H, Kamimura M, Sekimizu K. Activation of the silkworm cytokine by bacterial and fungal cell wall components via a reactive oxygen species-triggered mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(4):2185–91. Epub 2007/10/20. doi: M705480200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M705480200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roth O, Kurtz J. Phagocytosis mediates specificity in the immune defence of an invertebrate, the woodlouse Porcellio scaber (Crustacea: Isopoda). Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33(11):1151–5. Epub 2009/05/07. 10.1016/j.dci.2009.04.005 S0145-305X(09)00084-6 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaito C, Kurokawa K, Matsumoto Y, Terao Y, Kawabata S, Hamada S, et al. Silkworm pathogenic bacteria infection model for identification of novel virulence genes. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56(4):934–44. Epub 2005/04/28. doi: MMI4596 [pii] 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04596.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaito C, Akimitsu N, Watanabe H, Sekimizu K. Silkworm larvae as an animal model of bacterial infection pathogenic to humans. Microb Pathog. 2002;32(4):183–90. Epub 2002/06/25. 10.1006/mpat.2002.0494 S0882401002904948 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bartonwillis PA, Wang MC, Holliday MJ, Long MR, Keen NT. Purification and Composition of Lipopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas-Syringae Pv Glycinea. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1984;25(3):387–98. 10.1016/0048-4059(84)90045-6 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ishii K, Hamamoto H, Imamura K, Adachi T, Shoji M, Nakayama K, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidoglycans induce excessive activation of the innate immune system in silkworm larvae. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(43):33338–47. Epub 2010/08/13. 10.1074/jbc.M110.112987 M110.112987 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Silkworms were fed a normal diet or a diet containing heat-killed microbial cells for 2 d, and then injected with living microbial cells. Experimental conditions and statistical analysis for each experiment are presented in S1 Table.

(TIF)

Silkworms were fed a normal diet or a diet containing lipopolysaccharide or peptidoglycan for 2 d, and then injected with living P. aeruginosa cells. Experimental conditions and statistical analysis for each experiment are presented in S2 Table.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.