Abstract

The identification of immune correlates of HIV control is important for the design of immunotherapies that could support cure or antiretroviral therapy (ART) intensification-related strategies. ART interruptions may facilitate this task through exposure of an ART partially reconstituted immune system to endogenous virus. We investigated the relationship between set-point plasma HIV viral load (VL) during an ART interruption and innate/adaptive parameters before or after interruption. Dendritic cell (DC), natural killer (NK) cell and HIV Gag p55-specific T-cell functional responses were measured in paired cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained at the beginning (on ART) and at set-point of an open-ended interruption from 31 ART-suppressed chronically HIV-1+ patients. Spearman correlation and linear regression modeling were used. Frequencies of plasmacytoid DC (pDC), and HIV Gag p55-specific CD3+ CD4− perforin+ IFN-γ+ cells at the beginning of interruption associated negatively with set-point plasma VL. Inclusion of both variables with interaction into a model resulted in the best fit (adjusted R2 = 0·6874). Frequencies of pDC or HIV Gag p55-specific CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells at set-point associated negatively with set-point plasma VL. The dual contribution of pDC and anti-HIV T-cell responses to viral control, supported by our models, suggests that these variables may serve as immune correlates of viral control and could be integrated in cure or ART-intensification strategies.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy interruption, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, set-point viral load

Introduction

The loss of viral control following HIV infection in the absence of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been associated with both viral and host factors such as in vivo viral diversity and clonal exhaustion,1–3 as well as with the loss and/or functional impediments of adaptive and innate cells.4–9 ART results in viral suppression, and restores, at least partially, adaptive functions (i.e. CD4+ T-cell counts,10 functional HIV-specific cell-mediated responses,11), and the frequency and function of innate effector cells,7 but is unable to result in life-long viral suppression and/or eradication.12–14 As a result, there is need for the development of strategies that could support cure or ART intensification-related strategies.

Innate and adaptive cell subsets and function have been shown to contribute to delayed progression to AIDS and/or protection from infection, suggesting that the identification of immune correlates of viral control could be important in the development of new strategies against HIV. Studies in long-term non-progressors, viraemic controllers, acutely infected early-treated patients interrupting therapy, or discordant couples have found that CD4+ T-cell lymphoproliferative responses, Gag-specific CD8+ T-cell responses, or frequency of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) are associated with lower viral replication in the absence of ART.15–21 Furthermore, studies in both humans and non-human primates suggest that during the post-acute phase of HIV infection, CD8+ T cells directed primarily against Gag correlate with viral suppression,22–27 whereas other studies suggest that the quality of CD8+ T-cell responses might also play a role in viral control.16,28–31 In addition to adaptive immune responses, the potential role of the innate immune system, particularly of natural killer (NK) cells and DC, in the establishment and control of HIV infection has also been supported by several reports demonstrating an inverse correlation between both numbers of mature NK cells and DC and HIV viral load (VL).7,9,32–34.

Intermittent treatment strategies have been explored for their ability to augment the ART-mediated immune recovery of anti-HIV-1 responses in chronically HIV-1+ patients, with the rationale that repeated, controlled antigenaemia may reactivate pre-existing responses and/or result in de novo immunization, yet they have failed to show a clear virological or immunological benefit of ART interruption.35–40 Although long-term ART interruption strategies have been associated with CD4 decline and increased risk of opportunistic infections, short-term ART interruptions (< 6 weeks) do not appear to negatively affect the rebound of CD4+ T-cell count to pre-interruption levels upon ART re-initiation and viral re-suppression.41

The levels of viral rebound during ART interruptions differ between individuals and seem to be related to a balance established by the immune system during primary infection.42,43 Hence, ART interruption strategies may still be used as a tool to investigate the mechanisms determining viral set-point, and to identify set-point correlates and reliable predictors. A single report has shown a negative association between pDC frequency and levels of HIV VL rebound during ART interruption in acute infection,42 so identifying pDC as a potential immune correlate of viral control. It remains unknown if the same would be observed in ART-treated patients after chronic HIV+ infection.

Based on findings from our previous study,44 showing that viral set-point did not differ during an open-ended ART interruption between chronically suppressed participants with or without preceding repeated ART interruptions, we evaluated retrospectively how ART-recovered innate and/or adaptive parameters associated with/or predicted viral set-point upon ART interruption by analysing cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) collected in our previous study before and at viral set-point of ART interruption.

Materials and methods

Participants

We evaluated cryopreserved PBMC obtained from 31 ART-suppressed chronically HIV-1 infected patients at the beginning (on ART) and at set-point of an open-ended ART interruption. Set-point plasma HIV VL was defined as the average plasma HIV-1 RNA of the first three consecutive measures with < 0·5 log difference. Although pre-interruption PBMC samples were available for all 31 patients, 15 of the 31 participants had available set-point PBMC samples. Any data point not collected because of the limitations of cell yield at thaw was not included in the analysis, so accounting for any differences from the data of 31 or 15 participants presented for pre-interruption or set-point, respectively. All donors were part of a larger cohort of 42 chronically suppressed HIV-1 infected patients participating in a parent study based in Philadelphia (USA). A detailed characterization of the cohort has been published elsewhere;39 entry criteria for the parent study were age ≥ 18 years, ongoing ART (three or more drugs), current CD4 count > 400 cells/μl (nadir CD4 ≥ 100 cells/μl), and current plasma HIV VL < 50 copies/ml (> 6 months history of VL < 500 copies/ml). Informed consent was obtained according to the Human Experimentation Guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services and of the authors’ institutions. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Wistar Institute and Philadelphia Field Initiating Group for HIV-1 Trials.

Flow cytometry-based phenotypic characterization of innate immune cell subsets

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were thawed, washed twice with cold 1 × PBS, blocked with serum for 10 min at room temperature, and stained (0·5 × 106 PBMC per condition) for 30 min on ice with the following anti-human cell surface monoclonal antibody combinations: (i) CD3-Peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)Cy5.5, CD56- FITC, CD16-phycoerythrin (PE), HLA-DR-PECy7, CD161-allophycocyanin (APC), (ii) Lin-1-FITC, HLA-DR-APC, CD11c-PE, and (iii) Lin-1-FITC, HLA-DR-APC, CD123-PE. The following isotypes were used: IgG1-PerCPCy5.5, IgG1-FITC, IgG1-PE, IgG1-PECy7, IgG1-APC. After staining, cells were washed, incubated for 5 min at room temperature with 1 ml 1 × FACS Lyse, washed again, re-suspended in 100 μl FACS washing buffer, and analysed using a nine-colour CyAn cytofluorimeter (Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO) by collecting total PBMC and 50 000 live lymphocytes (the live lymphocytes which are a subset of total PBMC were defined by size and granularity in forward scatter/side scatter). Live cell gates were set manually, and detection thresholds were set according to isotype-matched negative controls. All monoclonal antibodies and buffers used were from Becton Dickinson (BD) Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Stainings 1, 2 and 3 allowed for the assessment of NK cells (defined as CD3− CD161+/− CD56+ CD16+), myeloid DC (mDC; defined as Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD11c+) and pDC (defined as Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high), respectively. Results were reported as % of total PBMC. Data analysis was performed using flojo software (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA).

Flow cytometry-based assessment of spontaneous and HIV Gag p55-specific T-cell degranulation/cytokine production

T-cell spontaneous and HIV-1-specific degranulation/cytokine production were assessed by flow cytometry-based measurement of CD107a, perforin and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in the presence or absence of in vitro stimulation with a mixture of 15-amino-acid peptides (15-mer) with their sequences overlapping by 11 amino acids and spanning the sequence of HIV p55 gag (SF2 strain) donated by BD Biosciences,45 (HIV-1 Gag p55 peptide pool of a total of 127 peptides including four alternate peptides numbered 28A, 29A, 30A and 31A to account for potential AA to DT mutations at amino acids 121–122 present in the MN strain of HIV). Briefly, PBMC were thawed, washed twice with cold 1 × PBS and incubated (0·5 × 106 per condition) for 4 hr at 37° with Brefeldin A (5 μg/ml, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MI) and CD107a-PE (10 μl per 0·5 × 106 cells) or corresponding isotype IgG1-PE in the absence (medium alone: negative control) or presence of in vitro stimulation with HIV-1 Gag p55 peptide pool (1·8–2 μg/ml/peptide; BD Biosciences) or Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (positive control, 5 μg/ml, Sigma Aldrich). At the end of the incubation cells were stained for 30 min on ice with cell surface monoclonal antibodies (CD3-PerCPCy5.5, CD4-APCCy7, or corresponding surface isotypes IgG1-PerCPCy5.5, IgG1-APCCy7) and then washed, fixed with 1 × FACS Lyse, permeabilized with FACS Perm, and stained with IFN-γ-PE (or FITC) and perforin-FITC (or corresponding intracellular isotypes IgG1-PE, IgG1-FITC). All antibodies and buffers used were from BD Biosciences. Cells were analysed as described above. T-cell subsets were defined as CD4+ T cells (CD3+ CD4+) or CD8+ T cells (CD3+ CD4−). Degranulating/cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells were defined as CD3+ CD4− perforin+ IFN-γ+, and CD3+ CD4− CD107a+ IFN-γ+ cells. Antigen-specific responses were determined following subtraction of the background responses (no antigen stimulation).

Flow cytometry-based assessment of spontaneous and HIV Gag p55-specific T-cell proliferation, degranulation and cytokine production

T-cell spontaneous and HIV-1-specific proliferation, degranulation and cytokine production were assessed by flow cytometry as follows: upon thawing PBMC (0·5 × 106 per condition) were stained with CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer's instructions and then cultured for 4 days in the absence (medium alone: negative control) or presence of in vitro stimulation with an HIV-1 Gag p55 peptide pool (BD Biosciences, 1·8–2 μg/ml/peptide) or S. aureus enterotoxin B (positive control, 5 μg/ml, Sigma Aldrich). After a 4-day culture, cells were stained for CD3, CD4, CD107a and IFN-γ as described above. All antibodies and buffers used were from BD Biosciences. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were defined as described above. Since CFSE intensity is halved at each cell division, proliferating T cells (CD4+ or CD8+) were defined as CD3+ CD4+ CFSElo and CD3+ CD4− CFSElo cells. Proliferating/degranulating CD8+ T cells were defined as CD3+ CD4− CFSElo CD107a+ cells, whereas proliferating/cytokine-producing T cells (CD4+ or CD8+) were defined as CD3+ CD4+ CFSElo IFN-γ+, and CD3+ CD4− CFSElo IFN-γ+ cells. Antigen-specific responses were determined as described above.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized as medians, 25% and 75% centiles (interquartile range, IQR), means, standard deviation, minimum and maximum. For analysis and graphing purposes plasma HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/ml was considered as equal to 50 copies/ml (threshold of detection). Spearman's rank correlation of set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml) with absolute values, or with the absolute difference between antigen-stimulated and unstimulated values, measured at onset or set-point of ART interruption, were performed. Correlations were considered meaningful for Rho values > 0·3 with P < 0·05. To assess the contribution of the study variables at the beginning of ART interruption to set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml) multivariate linear regression models were applied using pre-interruption innate (pDC, mDC, NK) and adaptive [CD8+ T cells degranulation/cytokine production (perforin+ IFN-γ+, CD107a+)] variables as predictors. A backward elimination procedure was applied to select the predictors and the final model was selected based on the highest adjusted R2. All statistical analysis was carried out using R.2.5.1 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Plasma HIV VL reaches set-point during ART interruption

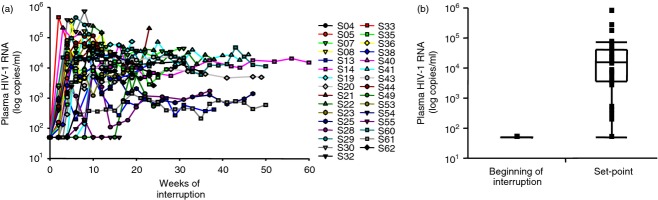

The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients whose samples were used in the current study are shown in Table1. The median CD4 count before ART interruption was 669 cells/μl (IQR 513–808), while all patients had VL < 50 copies/ml. As expected, ART interruption resulted in viral rebound and set-point. The median CD4 count at set-point was 478 cells/μl (IQR 373–623·5). Plasma HIV VL for all subjects during ART interruption (median time for set-point = 67 days, IQR 56–99·75) is displayed in Fig.1(a), whereas the distribution of pre-interruption and set-point plasma HIV VL (median set-point VL = 16 153 copies/ml, IQR 36 443–41 042) is summarized in Fig.1(b).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information of patient cohort

| Patient | Year of birth | CD4 count at onset of ART interruption (cells/mm3) | Plasma HIV-1 RNA at onset of ART interruption (copies/ml) | CD4 count at set-point of ART interruption (cells/mm3) | Plasma HIV-1 RNA at set-point of ART interruption (copies/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S04 | 1962 | 585 | < 50 | 517 | 3325 |

| S05 | 1952 | 307 | < 50 | 284 | 70 489 |

| S07 | 1941 | 1022 | < 50 | 608 | 37 906 |

| S08 | 1948 | 426 | < 50 | 228 | 164 904 |

| S13 | 1958 | 808 | < 50 | 670 | 507 |

| S14 | 1972 | 782 | < 50 | 858 | 16 153 |

| S19 | 1962 | 425 | < 50 | 250 | 48 288 |

| S20 | 1978 | 708 | < 50 | 611 | 3961 |

| S21 | 1962 | 509 | < 50 | 340 | 31 673 |

| S22 | 1952 | 1007 | < 50 | 704 | 27 692 |

| S23 | 1954 | 621 | < 50 | 433 | 44 178 |

| S25 | 1965 | 886 | < 50 | 834 | 2692 |

| S28 | 1953 | 478 | < 50 | 475 | 274 |

| S29 | 1957 | 513 | < 50 | 384 | 264 688 |

| S30 | 1957 | 602 | < 50 | 345 | 750 000 |

| S32 | 1961 | 864 | < 50 | 677 | 21 961 |

| S33 | 1953 | 901 | < 50 | ||

| S35 | 1952 | 516 | < 50 | 464 | 7260 |

| S36 | 1962 | 426 | < 50 | 320 | 4687 |

| S38 | 1960 | 688 | < 50 | 507 | 8460 |

| S40 | 1947 | 594 | < 50 | ||

| S41 | 1948 | 766 | < 50 | 421 | 21 246 |

| S43 | 1951 | 690 | < 50 | 409 | 13 674 |

| S44 | 1958 | 374 | < 50 | 362 | 63 255 |

| S49 | 1948 | 557 | < 50 | 517 | 50 |

| S53 | 1964 | 1320 | < 50 | 701 | 6572 |

| S54 | 1960 | 832 | < 50 | 636 | 21 456 |

| S55 | 1964 | 615 | < 50 | 589 | 192 |

| S60 | 1952 | 669 | < 50 | 469 | 16 249 |

| S61 | 1969 | 775 | < 50 | 478 | 383 |

| S62 | 1955 | 720 | < 50 | 579 | 6423 |

Figure 1.

Plasma HIV viral load (VL) reaches set-point during antiretroviral therapy (ART) interruption. (a) Plasma HIV VL (HIV-1 RNA copies/ml) during open-ended ART interruption (n = 31). (b) Plasma HIV VL at the beginning (n = 31) and at set-point of ART interruption (n = 31). Data in panel (a) are shown per patient during follow up, and in panel (b) they are shown as IQR boxes (median, and outliers).

Association of pre-interruption pDC frequency and HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses with set-point plasma HIV VL

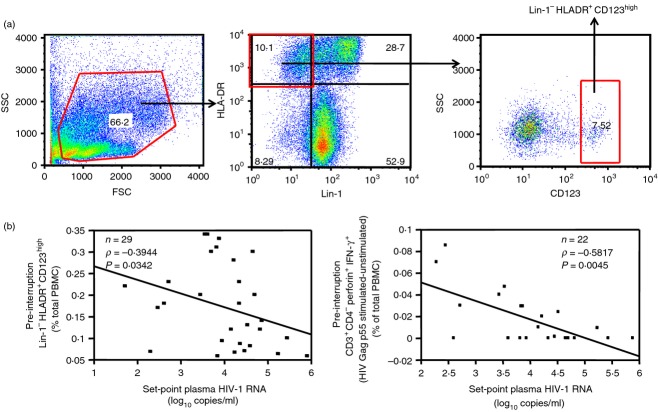

The association between set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml) and pre-interruption frequency of innate cell subsets (pDC, mDC, NK cells) or T-cell function (T-cell spontaneous and HIV-1 Gag p55-specific degranulation, cytokine production and proliferation) were assessed using Spearman's rank correlation tests; the results of this analysis are shown in Table2. Among innate parameters, we observed a significant negative association between set-point plasma HIV VL and pre-interruption frequency of pDC (n = 29, P = 0·0342, Rho = –0·3944, Table2, Fig.2 left panel) but not with any of the other innate cell subsets studied (i.e. mDC and NK cells). Among adaptive parameters, we observed a negative association between set-point plasma HIV VL and HIV Gag p55-specific CD8+ T-cell degranulation/cytokine production (perforin+ IFN-γ+) (n = 22, P = 0·0045, Rho = −0·5817, Table2, Fig.2 right panel).

Table 2.

Spearman's rank correlations between set-point plasma HIV viral load (log10 copies/ml) and variables at the beginning and at set-point of antiretroviral therapy (ART) interruption

| Variable (% of total peripheral blood mononuclear cells) | Beginning of ART interruption (on ART), P (Rho, n) | Set-point of ART interruption, P (Rho, n) |

|---|---|---|

| No stimulation | ||

| Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high | 0·0342 (−0·3944, 29) | 0·0187 (−0·6391, 13) |

| Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD11c+ | 0·1995 (−0·2844, 22) | 0·6419 (−0·1364, 14) |

| CD3− CD161+/− CD56+ CD16+ | 0·6479 (0·1286, 15) | 0·7208 (−0·1099, 13) |

| CD3+ CD4− perforin+ IFN-γ+ | 0·3889 (0·1932, 22) | 0·8396 (0·0572, 15) |

| CD3+ CD4− CD107a+ IFN-γ+ | 0·3235 (0·2105, 24) | 0·0017 (0·7382, 15) |

| CD3+ CD4+ CFSElo IFN-γ+ | 0·3911 (−0·1755, 26) | 0·4733 (−0·209, 14) |

| CD3+ CD4− CFSElo IFN-γ+ | 0·3435 (−0·1935, 26) | 0·6044 (−0·1518, 14) |

| CD3+ CD4− CFSElo CD107a+ | 0·8457 (0·0441, 22) | 0·4738 (−0·2066, 14) |

| CD3+ CD4+ CFSElo | 0·0217 (−0·4462, 26) | 0·4668 (−0·2036, 15) |

| CD3+ CD4− CFSElo | 0·2775 (−0·2212, 26) | 0·9195 (0·0286, 15) |

| HIV Gag p55–unstimulated | ||

| CD3+ CD4− perforin+ IFN-γ+ | 0·0045 (−0·5817, 22) | 0·8399 (0·0595, 14) |

| CD3+ CD4− CD107a+ IFN-γ+ | 0·3124 (0·2153, 24) | 0·1357 (0·4036, 15) |

| CD3+ CD4+ CFSElo IFN-γ+ | 0·4865 (−0·1428, 26) | 0·2306 (−0·3743, 12) |

| CD3+ CD4− CFSElo IFN-γ+ | 0·8238 (−0·0459, 26) | 0·1176 (−0·4762, 12) |

| CD3+ CD4− CFSElo CD107a+ | 0·5321 (0·1408, 22) | 0·0235 (−0·6209, 13) |

| CD3+ CD4+ CFSElo | 0·4979 (−0·1391, 26) | 0·1142 (−0·4595, 13) |

| CD3+ CD4− CFSElo | 0·5726 (−0·116, 26) | 0·0819 (−0·5, 13) |

Bold values indicate P < 0.05

Figure 2.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and T-cell HIV Gag p55-specific degranulation/cytokine production at the beginning of antiretroviral therapy (ART) interruption as a correlate of set-point plasma HIV viral load (VL). (a) Gating strategy for pDC (Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high cells). (b) Spearman's Rank correlation of set-point plasma HIV VL (HIV-1 RNA log10 copies/ml) with the frequency at the beginning of ART interruption of pDC [% of total peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)] (left panel), and HIV Gag p55-specific (p55 stimulated–unstimulated) CD3+ CD4− perforin+ IFN-γ+ cells (% of total PBMC) (right panel). Data in (b) are shown as regression lines with number of patients, Rho and P values included. Note that although Spearman's Rank correlations were performed, regression lines were used for graphic purposes only.

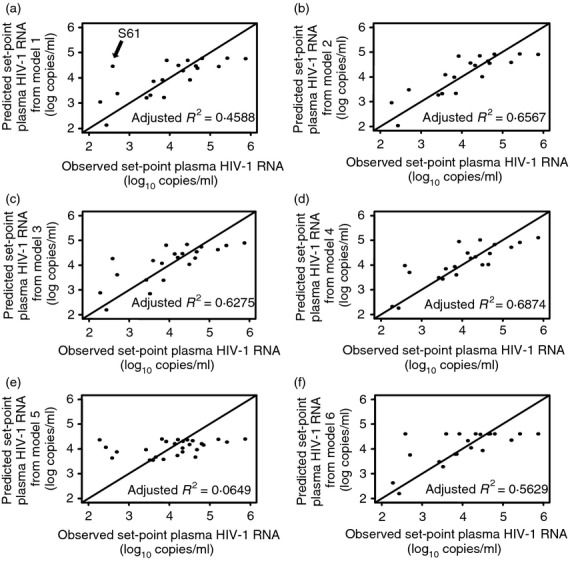

Multivariate linear regression models combining immune variables measured at the beginning of ART interruption were then used, to assess the combined effect of these variables on set-point plasma HIV VL. For each model shown, only patients with available data for all the variables analysed were included, thereby accounting for the different number of patients contributing in each model targeting different cluster of variables. Following backward elimination of predictors the model that included one innate (pDC), and two adaptive (CD107a+ CD8+ T cells, and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells) immune variables as independent predictors resulted in the best fit with an adjusted R2 = 0·4588 (model 1: Table3, Fig.3). An outlier (subject S-61) was detected by Grubbs outlier test,46 with a P value of 0·0175 when model diagnosis procedure was carried out for the residuals. To improve the model fitting, the outlier (subject S-61) was excluded and led to model 2, which gave an adjusted R2 = 0·6567 (model 2: Table3, Fig.3). Subsequent elimination from model 2 of CD107a+ CD8+ T cells from the set of the three predictors, resulting in the usage of pDC and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells as independent predictors, further improved the model (model 3, adjusted R2 = 0·6275; pDC P = 0·0528, and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells P < 0·0001, Table3, Fig.3). The addition of interaction terms for pDC and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells on model 3 resulted in a marginally better model (model 4: adjusted R2 = 0·6874, Table3, Fig.3) suggesting that pDC might have a positive effect on the association between set-point plasma HIV VL and HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell degranulation/cytokine production. Importantly, pDC alone were not predictive of set-point plasma HIV VL (P = 0·102, model 5, Table3, Fig.3), suggesting that any effect exerted by pDC should be in association with HIV-specific adaptive responses.

Table 3.

Final model selection using Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high and HIV Gag p55-specific Perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells at the beginning of ART interruption as predictors of set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml)

| Terms | Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high | Perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells | CD107a+ CD8+ T cells | Adj. R2 | F-statistic P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | ||

| 1 | −2·74 | 0·1279 | −25·62 | 0·0015 | 0·62 | 0·3125 | 0·4588 | 0·0048 |

| 21 | −2·54 | 0·0732 | −28·92 | < 0·0001 | 0·56 | 0·2374 | 0·6567 | 0·0002 |

| Terms | Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high | Perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells | Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high: Perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells | Adj. R2 | F-statistic P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | ||

| 31 | −2·51 | 0·0528 | −28·33 | < 0·0001 | – | – | 0·6275 | < 0·0001 |

| 41 | −4·47 | 0·0066 | −46·77 | 0·0002 | 112·56 | 0·05 | 0·6874 | < 0·0001 |

| 51 | −3·00 | 0·102 | – | – | – | – | 0·0649 | 0·1019 |

| 61 | – | – | −28·37 | < 0·0001 | – | – | 0·5629 | < 0·0001 |

Outlier (subject S-61) was excluded.

Figure 3.

Model selection using levels of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell degranulation/cytokine production at the beginning of antiretroviral therapy (ART) interruption as predictors of set-point plasma HIV viral load (VL). Effect on set-point plasma HIV VL (HIV-1 RNA log10 copies/ml) using the following variables measured at the beginning of ART interruption as predictors: (a) pDC, CD107a+ CD8+ T cells, and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells as independent predictors (model 1), (b) pDC, CD107a+ CD8+ T cells and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells as independent predictors following the exclusion of an outlier (subject S-61, model 2), (c) pDC and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells as independent predictors following the exclusion of an outlier (subject S-61, model 3), (d) pDC and HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells, including the addition of an interaction term and following the exclusion of an outlier (subject S-61, model 4), (e) pDC following the exclusion of an outlier (subject S-61, model 5), and (f) HIV Gag p55-specific perforin+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells following the exclusion of an outlier (subject S-61, model 6). In each model only patients with available data for all the variables included in that model were used. Data in panels (a–f) are shown as plots of predicted values for set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml) from corresponding models (axis y) against observed values for set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml) (axis x) with adjusted R2 values included. Lines in plots represent the perfect fit (x = y). Arrow in (a) indicates subject S-61 (outlier).

Plasmacytoid DC and HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell proliferation/degranulation at set-point as correlates of set-point plasma HIV VL

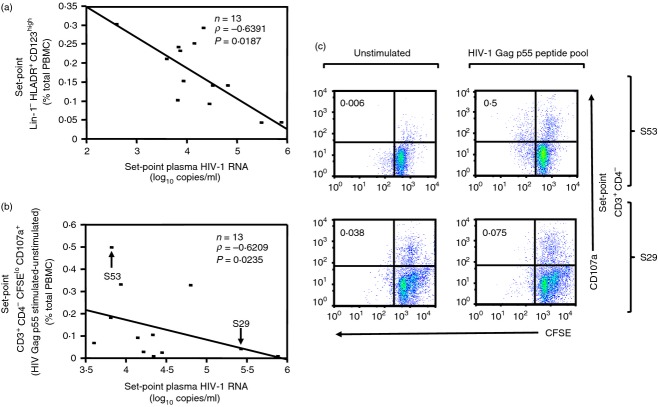

The association between set-point plasma HIV VL (log10 copies/ml) following ART interruption and innate and/or adaptive parameters (measured at set-point) was tested using Spearman's rank correlation tests. As noted in the Materials and methods section, although pre-interruption PBMC samples from all 31 patients were available, only 15 had available set-point PBMC samples. As shown in Table2, and in agreement with the findings at the onset of ART interruption, an inverse association was detected between set-point frequency of pDC and set-point plasma HIV VL (n = 13, P = 0·0187, Rho = −0·6391, Fig.4a). Interestingly, an inverse correlation was detected between set-point plasma HIV VL and set-point HIV Gag p55-specific CD8+ T-cell proliferation/degranulation (CSFElo CD107a+) (n = 13, P = 0·0235, Rho = −0·6209, Table2, Fig.4b,c) in accordance with previous reports in HIV-infected non-progressors.47

Figure 4.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and HIV Gag p55-specific proliferation/degranulation at set-point as correlates of set-point plasma HIV viral load (VL). (a) Spearman's Rank correlation of pDC frequency (Lin-1− HLA-DR+ CD123high cells) [% of total peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)] at set-point of antiretroviral therapy (ART) interruption with set-point plasma HIV VL (HIV-1 RNA log10 copies/ml). (b) Spearman's Rank correlation of HIV Gag p55-specific (p55 stimulated–unstimulated) CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells (% of total PBMC) at set-point of ART interruption with set-point plasma HIV VL. Subject S61 [CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells (% of total PBMC) in vitro HIV Gag p55–unstimulated = 4·03], although included in the analysis, is not shown in (b) for graphic purposes. Examples of data distribution for high (S53) and low (S29) responder per CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells (% of total PBMC) in the presence of stimulation with HIV-1 Gag p55 peptide pool are indicated in corresponding quadrants in (c). (c) Two representative donors for high and low response measured as CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells (% of total PBMC) in the presence of stimulation with HIV-1 Gag p55 peptide pool are shown. Top panel shows subject S53: set-point plasma HIV VL = 3·81 copies/ml, CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells (% of total PBMC): no stimulation = 0·006 (left), in vitro HIV Gag p55 = 0·5 (right), in vitro HIV Gag p55–unstimulated = 0·49. Bottom panel shows subject S29: set-point plasma HIV VL = 5·42 copies/ml, CD3+ CD4− CSFElo CD107a+ cells (% of total PBMC): no stimulation = 0·038 (left), in vitro HIV Gag p55 = 0·075 (right), in vitro HIV Gag p55–unstimulated = 0·037. Data in (a) and (b) are shown as regression lines with number of patients, Rho and P values included. Note that although Spearman's Rank correlations were performed, regression lines were used for graphic purposes only. Arrows in (b) indicate the two representative subjects (S53 and S29) shown in detail in (c).

Discussion

We provide the first report identifying a model where frequency of pDC and HIV Gag p55-specific CD8+ perforin+ IFN-γ+ T cells when measured on ART before a treatment interruption can inform set-point plasma HIV VL after interruption. Our data strongly suggest that correlates of viral control off ART may be best evaluated by joining innate and adaptive measures rather than using single isolated variables.

Although several innate cell subsets contribute to pathogen responses, only pDC were found in our study to be associated with set-point plasma HIV VL when measured as a single variable on ART. Indeed, the observation that the pDC frequency in ART-suppressed chronically HIV-1+ subjects undergoing ART interruption is negatively correlated with post-ART interruption set-point supports the report of Pacanowski et al.,42 who reported the same finding in a smaller group of seven primary infected subjects treated for 1 month with ART before a subsequent ART interruption. Interestingly, variance in pDC frequency on ART maintaining a negative relationship with subsequent viral set-point off ART is also consistent with our earlier reports noting a negative relationship between degree of immune reconstitution in pDC frequency after ART and pre-ART plasma HIV VL.7 With regards to adaptive responses, the negative correlation of set-point plasma HIV VL and HIV Gag p55-specific CD8+ perforin+ IFN-γ+ T cells at the beginning of ART interruption, observed in this study, suggests that HIV control requires effector CD8+ T cells able to produce IFN-γ in conjunction with perforin. We interpret that the quality of immune reconstitution with regards to pDC recovery on ART may be a determinant to innate-adaptive cross-talk that may affect the antiviral capacity of the CD8+ T-cell response.

When evaluating immune correlates of viral control once set-point off ART is defined, a negative correlation between set-point plasma HIV VL and set-point frequency of HIV Gag p55-specific CD8+ CSFElo CD107a+ T cells indicated that measures of correlates of control may be dependent on whether they are measured with/or without viraemia present, as IFN-γ/perforin content and not CSFE/CD107a emerged as a correlate of control when measured without viraemia and on ART. Finding that HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells with proliferating/degranulating activity (as defined by CFSE dilution and CD107a expression, respectively) are a correlate of viral control without ART is in agreement with data from studies in non-human primates and elite controllers.22,26,47–49 Future studies would need to assess whether reports of HIV Gag-specific cellular responses, as associated with lower VL,25,27,50,51 may yield stronger correlates of control after taking pDC frequency into account, as suggested by our data.

Importantly, we interpret that pDC effects may reflect dual support of innate and HIV-specific adaptive responses by exerting a positive effect on NK cell and T-cell cytotoxicity as well as T-cell perforin content.52–55 Our study raises the hypothesis that the frequencies of Gag-specific T cells and pDC on ART may predict the level of viral control following ART interruption. In support of this hypothesis, combined administration of IFN-α (as a product of pDC) and ART in chronically HIV-infected subjects has been shown by our group to exert greater viral control after ART interruption when compared with subjects treated only with ART.56 In addition, an independent set of data from our laboratory also shows that the combination of pDC frequency and HIV Gag-specific CD8+ T cells can best model viral control in the absence of ART among viraemic suppressors,57 further supporting the strong potential interplay between innate and adaptive mechanisms accounting for HIV control. Future studies will now need to integrate additional host control variables such as IFN-induced gene expression of host anti-viral proteins (Tetherin and APOBEC).

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis did not include an adjustment for multiple testing due to our limited sample size from 31 patients (yet still higher from other studies with similar findings, i.e. the study of Pacanowski et al.,42 in seven patients) and in keeping with the exploratory nature of our report. As a result, our findings are in need of validation by future studies with a larger sample size. We expect that having identified a specific combination of innate and adaptive variables that inform viral set-point after ART interruption may facilitate future validation of our conclusions. Second, no live/dead marker was included in staining. Cells targeted for analysis were initially defined by size and granularity associated with live cell fractions (forward scatter/side scatter) before further cell-specific gating. Although this gating strategy does not exclude all dead cells in the first target gate, subsequent validation tests by re-staining the same samples with a live/dead marker established that the numbers of dendritic cell subsets in the final cell-specific gate were comparable. Although functional antigen-specific T-cell responses above unstimulated are dependent on the live cell fraction and these responses as measured did correlate with viral load, it remains possible that a greater magnitude of response may have been observed with the inclusion of a live/dead marker. Third, we could not address the functionality of innate immune subsets due to specimen limitations. Future studies will be required to investigate the mechanism underlying the observed negative association between set-point plasma HIV VL and pDC frequency. Fourth, although cytokine expression was directly measured, the cytolytic function of T cells against HIV-infected targets was not addressed directly but rather interpreted from joint measurements of perforin, and antigen-specific degranulation (CD107a expression).

Taken together, our data suggest a dual contribution of innate and adaptive mechanisms in determining the levels of viral control to be achieved after ART interruption, and thus support a shift away from evaluating only adaptive cell function when defining what may account for viral control in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the HIV-1 patients who participated in the study and their providers. We would also like to thank Brian Thiel and Maxwell Pistilli for technical assistance. Research reported was supported by the following awards: AI48398 (LJM), AI073219 (LJM), and AI056983 (AF). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Additional support was provided by The Philadelphia Foundation (Robert I. Jacobs Fund), Henry S. Miller, Jr and J. Kenneth Nimblett, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Universal Research Enhancement Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health, and Penn Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI 045008). Support for Shared Resources used in this study was provided by Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA010815 to the Wistar Institute.

Glossary

- APC

allophycocyanin

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- DC

dendritic cell

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IQR

interquartile range

- mDC

myeloid DC

- NK

natural killer

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- pDC

plasmacytoid DC

- PE

phycoerythrin

- PerCP

peridinin chlorophyll protein

- VL

viral load

Disclosures

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- Altfeld M, Rosenberg ES, Shankarappa R, et al. Cellular immune responses and viral diversity in individuals treated during acute and early HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2001;193:169–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malim MH, Emerman M. HIV-1 sequence variation: drift, shift, and attenuation. Cell. 2001;104:469–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleo G, Soudeyns H, Demarest JF, et al. Evidence for rapid disappearance of initially expanded HIV-specific CD8+ T cell clones during primary HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasavvas E, Kostman JR, Thiel B, et al. HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses in chronically HIV-1 infected blippers on antiretroviral therapy in relation to viral replication following treatment interruption. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26:40–54. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-7518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. 2002;8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appay V, Nixon DF, Donahoe SM, et al. HIV-specific CD8+ T cells produce antiviral cytokines but are impaired in cytolytic function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:63–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehimi J, Campbell DE, Azzoni L, et al. Persistent decreases in blood plasmacytoid dendritic cell number and function despite effective highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased blood myeloid dendritic cells in HIV-infected individuals. J Immunol. 2002;168:4796–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaghy H, Pozniak A, Gazzard B, Qazi N, Gilmour J, Gotch F, Patterson S. Loss of blood CD11c+ myeloid and CD11c– plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with HIV-1 infection correlates with HIV-1 RNA virus load. Blood. 2001;98:2574–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzoni L, Papasavvas E, Chehimi J, Kostman JR, Mounzer K, Ondercin J, Perussia B, Montaner LJ. Sustained impairment of IFN-γ secretion in suppressed HIV-infected patients despite mature NK cell recovery: evidence for a defective reconstitution of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2002;168:5764–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors M, Kovacs JA, Krevat S, et al. HIV infection induces changes in CD4 + T-cell phenotype and depletions within the CD4+ T-cell repertoire that are not immediately restored by antiviral or immune-based therapies. Nat Med. 1997;3:533–40. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med. 1999;5:512–7. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtado MR, Callaway DS, Phair JP, Kunstman KJ, Stanton JL, Macken CA, Perelson AS, Wolinsky SM. Persistence of HIV-1 transcription in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells in patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1614–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl V, Josefsson L, Palmer S. HIV reservoirs, latency, and reactivation: prospects for eradication. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaz MJ, Waters A, Murad S, Easterbrook PJ, Vyakarnam A. Presence of HIV-1 Gag-specific IFN-γ+ IL-2+ and CD28+ IL-2+ CD4 T cell responses is associated with nonprogression in HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:6376–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers WA, Riou C, Mlotshwa M, et al. Association of HIV-specific and total CD8+ T memory phenotypes in subtype C HIV-1 infection with viral set point. J Immunol. 2009;182:4751–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster SE, Newton P, Cornforth D, Lifson JD, Williams I, Shaw GM, Borrow P. Association of strong virus-specific CD4 T cell responses with efficient natural control of primary HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2004;18:749–55. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MR, van Baalen CA, Holwerda AM, et al. Kinetics of Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses during the clinical course of HIV-1 infection: a longitudinal analysis of rapid progressors and long-term asymptomatics. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1365–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg ES, Billingsley JM, Caliendo AM, Boswell SL, Sax PE, Kalams SA, Walker BD. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–50. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontesilli O, Carotenuto P, Kerkhof-Garde SR, Roos MT, Keet IP, Coutinho RA, Goudsmit J, Miedema F. Lymphoproliferative response to HIV type 1 p24 in long-term survivors of HIV type 1 infection is predictive of persistent AIDS-free infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:973–81. doi: 10.1089/088922299310485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland-Jones SL, Dong T, Dorrell L, et al. Broadly cross-reactive HIV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes in highly exposed persistently seronegative donors. Immunol Lett. 1999;66:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Bauer DE, Tuttleton SE, et al. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1999;189:991–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MB. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1994;68:6103–10. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough TC, Brettler DB, Somasundaran M, Panicali DL, Sullivan JL. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), virus load, and CD4 T cell loss: evidence supporting a protective role for CTL in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:118–25. doi: 10.1086/514013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland M, Heckerman D, Deng W, et al. Broad and Gag-biased HIV-1 epitope repertoires are associated with lower viral loads. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, et al. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–60. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga R, Lucchetti A, Galvan P, et al. Relative dominance of Gag p24-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is associated with human immunodeficiency virus control. J Virol. 2006;80:3122–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.3122-3125.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addo MM, Draenert R, Rathod A, et al. Fully differentiated HIV-1 specific CD8 + T effector cells are more frequently detectable in controlled than in progressive HIV-1 infection. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts MR, Casazza JP, Koup RA. Monitoring HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses by intracellular cytokine production. Immunol Lett. 2001;79:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gea-Banacloche JC, Migueles SA, Martino L, et al. Maintenance of large numbers of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected progressors and long-term nonprogressors. J Immunol. 2000;165:1082–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masemola A, Mashishi T, Khoury G, et al. Hierarchical targeting of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteins by CD8+ T cells: correlation with viral load. J Virol. 2004;78:3233–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3233-3243.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehniger TA, Herbein G, Yu H, Para MI, Bernstein ZP, O'Brien WA, Caligiuri MA. Natural killer cells from HIV-1+ patients produce C-C chemokines and inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 1998;161:6433–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet V, Blauvelt A. Essential roles for dendritic cells in the pathogenesis and potential treatment of HIV disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:365–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal FP, Spear GT. Innate immunity and HIV. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl. 5):S127–37. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200100005-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzoni L, Papasavvas E, Montaner LJ. Lessons learned from HIV treatment interruption: safety, correlates of immune control, and drug sparing. Curr HIV Res. 2003;1:329–42. doi: 10.2174/1570162033485212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybul M, Chun TW, Yoder C, et al. Short-cycle structured intermittent treatment of chronic HIV infection with highly active antiretroviral therapy: effects on virologic, immunologic, and toxicity parameters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15161–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261568398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybul M, Nies-Kraske E, Daucher M, et al. Long-cycle structured intermittent versus continuous highly active antiretroviral therapy for the treatment of chronic infection with human immunodeficiency virus: effects on drug toxicity and on immunologic and virologic parameters. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:388–96. doi: 10.1086/376535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard C, Oxenius A, Gunthard H, et al. A prospective trial of structured treatment interruptions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1220–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasavvas E, Kostman JR, Mounzer K, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of therapy interruption in chronic HIV-1 infection. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasavvas E, Foulkes A, Li X, Kostman JR, Mounzer KC, Montaner LJ. Evidence of a decrease in CD4 recovery once back on antiretroviral therapy after sequential > or =6 weeks antiretroviral therapy interruptions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:334–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181966b0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacanowski J, Develioglu L, Kamga I, Sinet M, Desvarieux M, Girard PM, Hosmalin A. Early plasmacytoid dendritic cell changes predict plasma HIV load rebound during primary infection. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1889–92. doi: 10.1086/425020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz RJ, Horn DL. Twenty years of therapy for HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 2003;9:867–73. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasavvas E, Kostman JR, Mounzer K, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of therapy interruption in chronic HIV-1 infection. PLoS Med. 2004;1:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maecker HT, Dunn HS, Suni MA, et al. Use of overlapping peptide mixtures as antigens for cytokine flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2001;255:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs FE. Sample criteria for testing outlying observations. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21:27–58. [Google Scholar]

- Migueles SA, Laborico AC, Shupert WL, et al. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/ni845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins MA, Wilson NA, Reed JS, Ahn CD, Klimentidis YC, Allison DB, Watkins DI. T-cell correlates of vaccine efficacy after a heterologous simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. J Virol. 2010;84:4352–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02365-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez-Cirion A, Lacabaratz C, Lambotte O, et al. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6776–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611244104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Douek DC, Bonhoeffer S, Brenchley JM, Casazza JP, Koup RA, Picker LJ. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J Virol. 2001;75:11983–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.11983-11991.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BH, Bansal A, Sabbaj S, Bakari J, Mulligan MJ, Goepfert PA. Magnitude of functional CD8+ T-cell responses to the gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 correlates inversely with viral load in plasma. J Virol. 2002;76:2298–305. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2298-2305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmuth DM, Murphy RL, Rosenkranz SL, et al. Safety, tolerability, and mechanisms of antiretroviral activity of pegylated interferon Alfa-2a in HIV-1-monoinfected participants: a phase II clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1686–96. doi: 10.1086/652420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi Y, Pitha PM. Alpha interferon inhibits early stages of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication cycle. J Virol. 1992;66:1321–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1321-1328.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portales P, Reynes J, Rouzier-Panis R, Baillat V, Clot J, Corbeau P. Perforin expression in T cells and virological response to PEG-interferon α2b in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2003;17:505–11. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomescu C, Chehimi J, Maino VC, Montaner LJ. NK cell lysis of HIV-1-infected autologous CD4 primary T cells: requirement for IFN-mediated NK activation by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:2097–104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzoni L, Foulkes AS, Papasavvas E, et al. Pegylated Interferon α2a monotherapy results in suppression of HIV type 1 replication and decreased cell-associated HIV DNA integration. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:213–22. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomescu C, Liu Q, Ross BN, Yin X, Lynn K, Mounzer KC, Kostman JR, Montaner LJ. A correlate of HIV-1 control consisting of both innate and adaptive immune parameters best predicts viral load by multivariable analysis in HIV-1 infected viremic controllers and chronically-infected non-controllers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e103209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]