Abstract

Objective

We aimed at summarising rates and factors associated with retention in HIV care prior to antiretroviral treatment (ART) eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa.

Design

We conducted a systematic literature review (2002–2014). We searched Medline/Pubmed, Scopus and Web of Science, as well as proceedings of conferences. We included all original research studies published in peer-reviewed journals, which used quantitative indicators of retention in care prior to ART eligibility.

Participants

People not yet eligible for ART.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Rate of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility and associated factors.

Results

10 papers and 2 abstracts were included. Most studies were conducted in Southern and Eastern Africa between 2004 and 2011 and reported retention rates in pre-ART care up to the second CD4 measurement. Definition of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility differed substantially across studies. Retention rates ranged between 23% and 88% based on series ranging from 112 to 10 314 individuals; retention was higher in women, individuals aged >25 years, those with low CD4 count, high body mass index or co-infected with tuberculosis, and in settings with free cotrimoxazole use.

Conclusions

Retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa has been insufficiently described so far leaving major research gaps, especially regarding long-term retention rates and sociodemographic, economic, clinical and programmatic logistic determinants. The prospective follow-up of newly diagnosed individuals is required to better evaluate attrition prior to ART eligibility among HIV-infected people.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This literature review is one of the first to summarise the scientific knowledge on retention in care (including definitions, rates and factors associated) prior to antiretroviral treatment (ART) eligibility among adults in sub-Saharan Africa.

It is based on a systematic screening of the published literature in three large databases as well as of proceedings of HIV conferences.

Few studies were included according to our inclusion criteria. Although we aimed to conduct an exhaustive review of the published literature, we cannot exclude that we missed some that did not correspond to our search equation.

Also considering that the definitions of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility varied substantially, we decided not to conduct a meta-analysis.

Introduction

In 2012, it was estimated that 22.1 million adults were living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, of whom 1.4 million were newly infected.1 To prevent HIV transmission and help those who live with HIV to have access to care and treatment in due time, the consensus today is that individuals should be diagnosed as early as possible in the course of HIV infection, that is to say, before eligibility criteria for antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation are met. Once an individual is diagnosed HIV positive, there are several steps up to ART initiation, known as the HIV cascade:2–4 (1) from HIV diagnosis to linkage to HIV care, (2) from linkage to HIV care to ART eligibility, (3) from ART eligibility to ART initiation. Continuum in HIV care through these different steps is critical for individuals to receive adequate clinical and biological monitoring, and to initiate ART immediately on becoming eligible in order to minimise early morbidity and mortality. It has indeed been shown that people who engaged in HIV care prior to eligibility were more likely to initiate and remain on ART than those entering in care when already eligible,5 6 and that the risk of mortality was reduced if ART was initiated early enough in the course of HIV infection.7 Finally, being in pre-ART care for more than 6 months was significantly associated with reduced rates of mortality and loss to follow-up after starting ART.8

In sub-Saharan Africa, many people are lost to follow-up between HIV diagnosis and ART initiation and these individuals are thus at risk of delayed ART initiation.9 Although the 2013 WHO recommendations for initiating ART reduce the length of time before reaching ART eligibility,10 ART eligibility criteria in most African countries are based on a CD4 <350 cells/µL threshold, and it will probably take time for these countries to expand their ART eligibility criteria and translate the WHO recommendation into practice. In the evolving context where many interventions are developed, evaluated and implemented with the aim of increasing the uptake of HIV testing among people early in the course of HIV infection,11 retention in care prior to ART eligibility is a key issue that needs to be better understood.

Three literature reviews have been conducted on HIV care prior to ART initiation in recent years,2–4 but they mostly focused on linkage to care and provided very little information on retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility as well as on risk factors for retention. In this paper, we have thus focused on this second step of the HIV cascade. We specifically aimed at summarising the scientific knowledge on retention in care prior to ART eligibility (definition, rates and risk factors) among adults in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Data source and search strategy

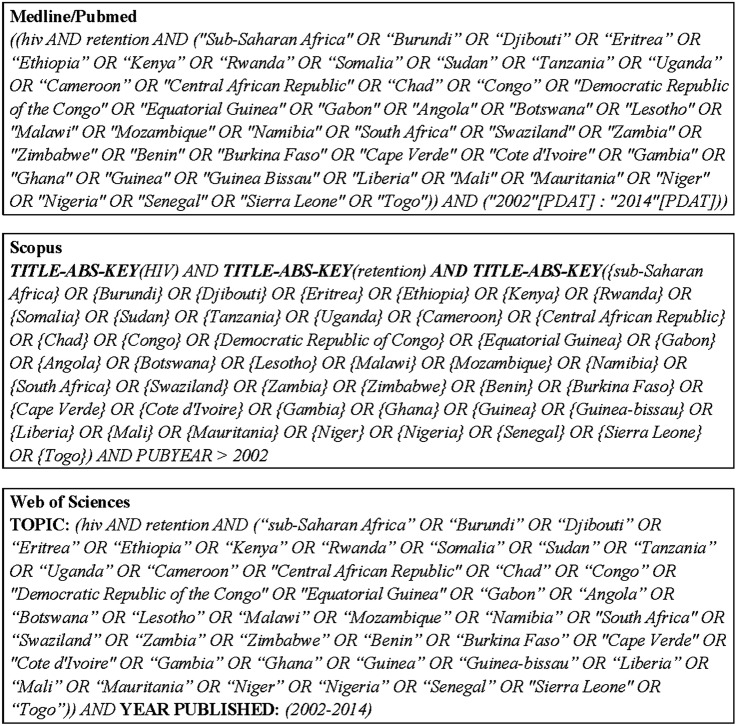

We conducted a systematic literature review on retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa searching MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus (which contains EMBASE references) and Web of Science until 21 January 2014. This review of published literature was conducted using a research equation combining these following free-text words: HIV, retention, and a list of all the African countries (except Maghreb) (figure 1). In addition, we also screened the abstracts of three major HIV conferences (CROI, IAS and ICASA) that took place between 2011 and 2013.

Figure 1.

Search strategy for the systematic literature review on retention in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa (January 2014).

Eligibility criteria and study selection

We included all original research studies published in peer-reviewed journals between 1 January 2002 and 21 January 2014, and those that used quantitative indicators of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility. We first excluded papers from title and abstract screening, if (1) the major subject was not HIV, (2) papers did not focus on linkage or retention in HIV care, (3) papers were not original studies or were modelling studies or methodological papers without original data, (4) papers were focused on a specific population such as children, adolescents, men who have sex with men, sex workers and migrants, (5) studies took place outside sub-Saharan Africa, (6) reports were based only on qualitative indicators, (7) papers were focused on post-ART retention, (8) papers focused only on linkage to HIV or ART initiation. We did not specify any language restriction. After reading full-text papers, we secondarily excluded papers that did not report explicitly on retention in care prior to ART eligibility, or if the definition of retention was not specified. We did not apply any specific quality criteria to the assessment beyond the strict reference selection criteria. For conferences proceedings, we first selected the tracks and sessions where the topic corresponded to our literature review. Selection was then carried out after systematic abstract screening. Authors of the papers and abstracts included were systematically contacted in case of missing information. The choice of inclusion criteria and the selection of references involved all the members of the research team. Only one researcher then reviewed the paper contents and abstracted the data.

Parameters of interest

For each study included, we reported definition and rate of retention in care prior to ART eligibility, and we presented cumulative incidence rates of retention at different time points. These rates are displayed in a bubble graph taking into account the population size for each study. We distinguished between retention documented between the first and the second CD4 measurement, or after the second measurement, and describe how deaths and transfers were considered for estimating the retention rate. We also indicated the follow-up duration considered when measuring the retention rate. Finally, we presented factors associated with retention in pre-ART care when they were reported in multivariable analysis. These factors did not necessarily focus only on retention in care prior to ART eligibility, as most papers considered global retention in pre-ART care, from HIV diagnosis to ART initiation; when this was the case, we distinguished between the size of the overall population in pre-ART care and the size of the population not yet ART eligible. We did not report on associations when studies did not distinguish between factors associated with retention in pre-ART care and post-ART initiation.

Results

Paper selection

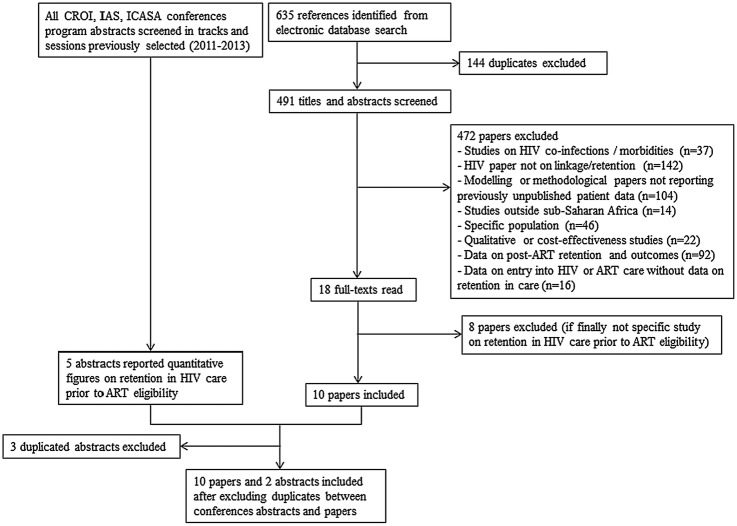

In total, 635 published references were identified through the search equation, of which 144 were duplicates and 472 others were excluded based on the title and abstract review (figure 2). Of the 18 remaining references, we left out eight papers after reading the full text. In addition, we also identified five studies from the conference proceedings search; three of them were excluded because they were duplicates. We thus included 10 published studies and12–21 two abstracts22 23 in this review.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of literature search on retention in HIV care prior to antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa (January 2014).

Studies characteristics

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 12 studies selected. One of them was conducted in three different countries; the other 11 were conducted in a single country. The majority of them took place in Southern and Eastern Africa: South Africa for four reports,13 14 18 19 Kenya for three,12 15 17 Uganda for two,12 20 and one each in Malawi,12 Mozambique21 and Zambia;23 only two studies were conducted in West Africa, namely Nigeria22 and Guinea-Bissau.16 All the studies were conducted between 2004 and 2012. Six of them were conducted in urban or periurban settings,13 14 16–18 22 two in rural settings15 19 and four in both contexts.12 20 21 23 Populations included were all individuals aged more than 15 years in four reports,12 15 21 23 more than 16 years in two;16 19 or more than 18 years in four;13 14 18 20 22 one study focused on pregnant women older than 18 years,13 and we did not have the information for the last one.17 ART eligibility criteria varied according to countries, and were based either on both CD4 cell count and WHO staging,12 15–17 21 23 or only on CD4 cell count.13 14 18–20 22 All these studies used data collected in cohorts from either clinics with NGO support or public HIV programmes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 12 sub-Saharan Africa studies included in the review of retention in HIV care prior to antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility

| Country (reference) | Year of the study | Urban/rural | Programmatic context | ART eligibility criteria | Population | Overall population size in pre-ART care | Population size prior to ART eligibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papers | |||||||

| Kenya, Malawi, Uganda12 | 2004–2011 | Rural and urban | HIV programmes supported by an NGO | Until January 2007: CD4 <200 or WHO stage IV Since January 2007: CD4 <200 or WHO stage III/IV Since March 2010: CD4 <350 or WHO stage III/IV |

≥15 years old | N=55 789 | N=10 314 |

| South Africa13 | 2010–2011 | Urban | Clinic operated by an NGO | CD4 ≤350 | Pregnant women ≥18 years old | N=271 | N=112 |

| South Africa14 | 2010–2011 | Urban | Clinic operated by an NGO | CD4 ≤350 | Non-pregnant adult ≥18 years old | N=842 | N=155 |

| Kenya15 | 2008–2010 | Rural | Public healthcare institution | CD4 <200 OR WHO stage III/IV OR no CD4 count and WHO staging at baseline | ≥15 years old and with HIV diagnosis <3 months before registration in care | N=530 | N=530 |

| Guinea-Bissau16 | 2005–2012 | Urban | National hospital | Undefined | ≥16 years old | N=484 | N=484 |

| Kenya17 | 2005–2007 | Urban | Clinic supported by an NGO | CD4 <250 or WHO stage III/IV | Not clear | N=1024 | N=1024 |

| South Africa18 | 2004–2009 | Periurban | Public clinic | CD4 <200 | ≥18 years old | N=419 | N=419 |

| South Africa19 | 2007–2008 | Rural | Public HIV programme | CD4 <200 | ≥16 years old | N=4223 | N=4223 |

| Mozambique21 | 2005–2009 | Rural and urban | National ART programme | WHO stage IV OR WHO stage III and CD4 <350 OR CD4 <200 | ≥15 years old | N=17 598 | N=12 992 |

| Uganda20 | 2008–2011 | Semirural and urban | Public HIV programme | CD4 <350 | ≥18 years old | N=6473 | N=6473 |

| Conferences abstracts | |||||||

| Nigeria22 | 2009–2012 | Urban | Unknown | CD4 <350 | ≥18 years old | N=414 | N=191 |

| Zambia23 | 2009–2010 | Rural and urban | District hospital | CD4 <250 OR WHO stage III/IV | ≥15 years old | N=145 | N=145 |

NGO, non-governmental organisation.

Retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility

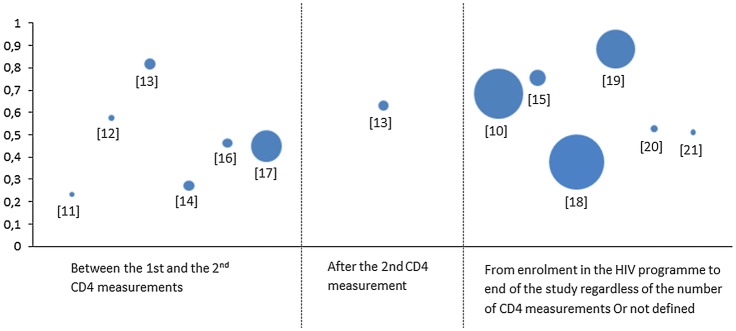

Table 2 and figure 3 summarise the study findings.

Table 2.

Retention in pre-ART care among patients who are not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART)

| Country (reference) | Period when retention was studied | Definition of retention | Retention time point | Rate of retention (%) | Consideration of deaths and transfers for calculating the rate | Factors associated with retention in pre-ART care | Factors investigated but not associated with retention in pre-ART care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papers | |||||||

| Kenya, Malawi, Uganda12 | From enrolment in the HIV programme to end of the study regardless of the number of CD4 measurements | Having missed an appointment for more than 6 months | Median: 18.4 months (IQR=8.5–32.2) | 68.4 | Deaths excluded Transfers excluded when reported |

Being old, female gender, BMI >18.5, low CD4 cell count, being diagnosed with TB, entry in VCT or PMTCT vs inpatient or outpatient services or medical referral, not eligible for ART at enrolment | |

| South Africa13 | Between the 1st and the 2nd CD4 measurements | Receiving a repeat CD4 count after delivery | 12 months | 23.2 | Transfers excluded when reported No deaths reported |

||

| South Africa14 | Between the 1st and the 2nd CD4 measurements | Receiving a second CD4 test within one year after the first CD4 staging | 12 months | 57.4 | Transfers excluded when reported Deaths not excluded |

≥30 years old, female gender, receiving TB treatment | Nationality, being employed, CD4 cell count |

| Kenya15 | Between the 1st and the 2nd CD4 measurements | Not being more than 60 days late for the scheduled appointment | Undefined | 81.9 | Deaths excluded Transfers excluded when reported |

Living ≤5 km from the main road, Not being single | Gender, age, entry point in care, religion, education level, season, population density, WHO staging, BMI |

| After the 2nd CD4 measurement | Not being more than 60 days late for the scheduled appointment after the second visit | Undefined | 63.2 | Deaths excluded Transfers excluded when reported |

Low education level, living ≤5 km from the main road, wet season | Gender, age, marital status, entry point, religion, population density, WHO staging, BMI, CD4, Hb | |

| Guinea-Bissau16 | Between the 1st and the 2nd CD4 measurements | Being less than 1 month late for the scheduled appointment | Median: 147 days (IQR=7–653) | 27.2 | Deaths excluded Transfers excluded when reported |

>30 years old, having anaemia, attending school, being infected by HIV-1 (vs HIV-2) | Sex, BMI, marital status, religion |

| Kenya17 | Undefined | Returning to clinic less than 30 days after the next scheduled pharmacy or clinic appointment | 12 months | 75.5 | Transfers excluded when reported Deaths not systematically taken into account |

Being older, high BMI, enrolled after free cotrimoxazole provision | Sex, TB status, baseline CD4 count |

| South Africa18 | Between the 1st and the 2nd CD4 measurements | Having a repeat CD4 count before 2009 | Undefined | 46.3 | Undefined | ≥30 years old | Sex, year of HIV test |

| South Africa19 | Between the 1st and the 2nd CD4 measurements | Repeating CD4 count within 13 months of the initial test | 13 months | 44.9 | No exclusion of deaths and transfers | Female gender, >25 years old, ≤350 CD4 cells/µL, not out-migrant, not full-time employed, not living in a household size >10 | |

| Mozambique21 | Undefined | Having less than 12 months elapsed since the last documented clinic visit | 12 months | 37.6 | Transfers and deaths excluded | Non-pregnant female, >25 years old, having at least finished primary school, weight >56 kg, no WHO stage I | Marital status, number of children, socioeconomic status, CD4 count, |

| Uganda20 | From enrolment in the HIV programme to the end of the study regardless of the number of CD4 measurements | Having seen an HIV provider in the 6 months before the interview | 30 months | 88.2 | Using of a weighing method for correcting the rate, taking into account all outcomes (transfers, deaths) after tracking | High income, employment, high weight, urban setting | Age, sex, CD4 level, education level, marital status, calendar date at enrolment |

| Conference abstracts | |||||||

| Nigeria22 | From enrolment in the HIV programme to the end of the study regardless of the number of CD4 measurements | No clinic appointment missed for three consecutive times | Undefined | 52.8 | No exclusion | Intervention package: provision of free cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, harmonised pharmacy and laboratory appointments, task-shifting to nurses and data-clerks, same-day CD4 monitoring and receipt of results, integrated clinic services | |

| Zambia23 | From enrolment in the HIV programme to the end of the study regardless of the number of CD4 measurements | No fail to return for an appointment on two and more occasion | 12 months | 51 | No details provided | ≥30 years old, >20 km from the hospital | Gender, marital status, education level, monthly outcome, partner's HIV status, WHO clinical stage, CD4 cell count |

Twelve studies in sub-Saharan Africa.

BMI, body mass index; Hb, haemoglobin; LTFU, loss to follow-up; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV; TB, tuberculosis; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

Figure 3.

Rates of retention in HIV care prior to antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa. Twelve studies in sub-Saharan Africa. Bubble size proportional to population size.

Definition of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility

Criteria used for the definition of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility varied across the 12 studies and depended mostly on programmatic factors. The majority of studies reported retention rates between the first and the second CD4 measurement,13–16 18 19 and only one study explicitly reported a retention rate after the second CD4 measurement.15 Other papers reported retention rates in HIV care prior to ART eligibility from enrolment of patients in the HIV programme to the end of the study regardless of the number of CD4 measurements.12 20 22 23 Almost all the studies did exclude death and/or transfers for studying retention in HIV care. One study used a tracking method ascertaining the vital status of a subsample of patients lost to follow-up for correcting the estimation of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility.20

Rates of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility

The lowest crude rate of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility was observed in the study focused on pregnant women (23%),13 followed by the study conducted in West Africa (27%);16 three other studies reported rates of retention lower than 50%.18 19 21 The highest crude rates of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility were observed in Kenya (82%)15 and in Uganda (88%).20

Factors associated with retention in pre-ART care

Retention in pre-ART care was mostly associated with individual factors, which varied according to settings. Factors that were most consistently found associated with a higher retention in pre-ART care included age above 25/30 years compared to the younger ones12 14 16–19 21 23 and female gender.12 14 19 One study also showed that non-pregnant women were more likely to be retained compared with men and pregnant women.21 Also, in Uganda, high income was significantly associated with better retention in pre-ART care.20 Religion and nationality were investigated but not reported to be associated with retention in pre-ART care.

Distance to the clinic was studied in two settings and showed conflicting results: in Kenya, people who lived ≤5 km (vs >5 km) away from the clinic were more likely to be retained in pre-ART care,15 while in Zambia people who lived ≤20 km (vs >20 km) from the clinic were more likely to be lost to follow-up.23 Biological and clinical factors were also associated with a higher retention in pre-ART care, including low CD4 cell count,12 19 high body mass index,12 17 heavier weight20 21 and anaemia.16 Additionally, retention in pre-ART care was higher in patients coinfected with tuberculosis.12 14

Lastly, two studies showed that the introduction of free cotrimoxazole increased retention in pre-ART care in Kenya17 and Nigeria.22 In Nigeria, in addition to the provision of free cotrimoxazole, the intervention package was also composed of synchronised pharmacy and laboratory appointments, task-shifting to nurse and data clerks, same day CD4 monitoring and receipt of results and integrated clinics.22

Discussion

Although many HIV-infected adults are deemed to be lost to follow-up before reaching ART eligibility, little research has been published on retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility; indeed, only 12 studies were included in this review over a 12-year period. Definitions of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility varied across settings and healthcare systems, thus making the comparison between studies challenging. Nevertheless, reported rates of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility were consistently low; this was especially the case among pregnant women13 and in West Africa (Guinea-Bissau).16 Only three studies reported a retention rate >75%.15 17 20

Clouse et al13 observed that retention in pre-ART care was much higher during pregnancy compared to the postdelivery period, and especially in women not yet eligible for ART, concluding that ‘among HIV-positive pregnant women, the challenge is to ensure that HIV care extends beyond the period of pregnancy and continues for the lifetime of the mothers’.13 High loss-to-follow-up rates within prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programmes have been consistently reported, regardless of the WHO recommendation (Option A or B), as shown in a meta-analysis,24 and also under the recent Option B+ as found in Malawi.25

As noted by several authors,13 14 18 21 misclassification of care transfers, incorrectly considered as failures to continue care, may have led to an underestimate of the rates of retention in HIV care. This may be particularly the case in the study conducted in Guinea-Bissau, where many people worked outside the city of Bissau during the crop season.16 Indeed, patients not retained in the study clinic may have continued HIV care elsewhere without informing their doctor or nurse. Only one study tried to account for this concern, using a tracking method to establish the updated status of a random sample of patients not retained in the initial study clinic setting.20 Once the vital status of people who were first considered as lost to follow-up was verified, the authors estimated a corrected rate of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility of 90%, much higher than the uncorrected estimate of 70%.

This literature review confirms that retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility is lower in younger individuals12 14 16–19 21 23 and in men,12 14 19 as it has been already reported in previous literature reviews exploring retention in HIV care overall.3 26 Some papers included in our review also suggest that biological and clinical factors are associated with retention in pre-ART care. Indeed, it was shown that patients who are coinfected with tuberculosis,12 14 as well as those who have anaemia,16 or those with low CD4 count,12 19 are more likely to be retained in pre-ART care than patients without these characteristics. These results suggest that it is important for programmes to focus attention during pre-ART care on younger individuals, men in general, and also on individuals with less advanced HIV disease, who may feel healthier. However, while tuberculosis co-infection27 and anaemia28 are HIV-related diseases, the association between these complications and retention in pre-ART care is only supported by limited evidence so far and needs to be further explored.

This literature review highlights several gaps in the knowledge on retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility. First, 10 of the 12 studies identified were conducted in eastern and southern Africa; reports from West Africa, where healthcare systems have been described as less efficient, are lacking. Second, three of these studies reported that, among patients with a second CD4 measurement, about 70% of individuals were still not ART-eligible at that time.14 19 21 However, only one paper focused on retention in HIV care beyond the second CD4 measurement,15 and three others reported retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility regardless of the number of CD4 measurements.12 20 22 As the consensus is that individuals should be diagnosed as early as possible in the course of HIV infection before becoming eligible for ART,11 and bearing in mind that the CD4 threshold for ART initiation has been recently enlarged,10 the period between HIV diagnosis and ART initiation is a critical one for optimising the care plan. Longer term retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility should thus be further documented. Third, further methods, such as tracking by peer educators and use of mobile technologies, could contribute to better retention and more correct estimations of retention,20 accounting for people who are retained in care in the overall health system, but outside a given study clinic. Lastly, the 12 studies included in our review showed that retention in pre-ART care was associated with sociodemographic and clinical individual factors. However, the role of programmatic and logistic factors (such as time/distance to clinic, waiting time in clinic, costs for transportation or looking after the children) was very rarely studied, as well as perceptions on HIV care at individual and community levels. Nevertheless, as discussed by Boyles et al,8 reasons for low retention in pre-ART care may include the lack of availability of comprehensive HIV care services and the perception that ART is only necessary in individuals who become sick, suggesting that these factors should be further explored as potential barriers to retention in pre-ART care.

The results of our review highlight the urgent need to continue designing and evaluating interventions aimed at improving retention in HIV care, especially for people not yet eligible for ART. To date, several interventions have targeted the improvement of ART adherence, for example, reminder services (such as mobile phones, text messaging and diary cards)29 30 and treatment supporters.30 These interventions should now be adapted for improving retention in pre-ART care, and especially before ART eligibility, too. Some interventions, such as CD4 point-of-care31 and involvement of community healthcare workers and peers counsellors,32 have already been shown to improve retention in pre-ART care but are insufficiently used. A combination of different interventions,32 33 adapted to the setting, will most often be necessary in helping the majority of people to remain in care up to ART initiation.

A limitation of this review is that we only found a few published studies exploring retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility. Although we aimed to conduct an exhaustive review of the published literature, we cannot exclude that we missed some that did not correspond to our search equation; however, we have searched three different and large databases and enlarged our search to HIV conference abstracts. Another limitation was that the definition of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility substantially varied across the studies reviewed, making it challenging to compile and compare the retention rates reported in the various studies. Considering the small number of studies included and the non-standardised definitions of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility, we could not conduct a meta-analysis. Finally, the generalisability of these findings needs to be done with caution; indeed, it is possible that only HIV programmes with better resources have analysed and published their data.

In conclusion, this literature review shows that, as more and more individuals are offered HIV testing earlier in the course of HIV infection, and as ART eligibility criteria are enlarged over time, rates of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility remain insufficient. Large-scale community randomised trials are currently evaluating the effectiveness of universal test-and-treat interventions, where ART initiation is initiated immediately after HIV testing, regardless of immunological or clinical criteria.34 35 Such an approach would a priori solve the issue of retention in HIV care prior to ART eligibility, and a recent report has shown good feasibility and acceptability in rural South Africa.36 However, even if test-and-treat strategies are shown to be effective in reducing HIV incidence at population levels, the time frame until their large-scale implementation is unclear. Thus, in the medium term, HIV care prior to ART eligibility does remain a challenge for healthcare systems and societies and deserves further consideration in sub-Saharan Africa. Longitudinal follow-up of newly HIV-diagnosed individuals tested under various circumstances would contribute to better characterise and understand attrition for those not yet eligible for ART in order to better guide local HIV care programmes. Finally, innovative support interventions, home or clinic based, will need to be evaluated on their capacity to retain this population in comprehensive HIV care services up to ART initiation, and thus prepare them better for lifelong ART and case management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evelyne Mouillet and Coralie Thore from ISPED, Bordeaux University for their help in the electronic database researches.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP, JO-G and RD-S conceived and designed the review. MP analysed the data. MP, RD-S, JO-G and FD wrote the paper.

Funding: Mélanie Plazy is supported by a PhD fellowship of the French National Agency for AIDS Research (ANRS).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf (accessed 7 Jul 2014).

- 2.Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N et al. . Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15:17383 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G et al. . Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:1509–20. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03089.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001056 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldacker C, Johnson D, Hosseinipour M et al. . Who starts? Factors associated with starting antiretroviral therapy among eligible patients in two, public HIV clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e50871 10.1371/journal.pone.0050871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plazy M, Dray-Spira R, Orne-Gliemann J et al. . Continuum in HIV care from entry to ART initiation in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:680–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X et al. . Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2008;22:1897–908. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyles T, Wilkinson L. How should we care for patients who are not yet eligible for ART? South Afr J HIV Med 2011;12:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: Results, impact and opportunities. 2013. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progressreports/update2013/en/index.html (accessed 7 Jul 2014).

- 10.WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf (accessed 7 Jul 2014). [PubMed]

- 11.WHO. Service delivery approaches to HIV testing and counselling (HTC): a strategic HTC programme framework. 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75206/1/9789241593877_eng.pdf (accessed 7 Jul 2014).

- 12.Bastard M, Nicolay N, Szumilin E et al. . Adults receiving HIV care before the start of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: patient outcomes and associated risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:455–63. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a61e8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clouse K, Pettifor A, Shearer K et al. . Loss to follow-up before and after delivery among women testing HIV positive during pregnancy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:451–60. 10.1111/tmi.12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clouse K, Pettifor AE, Maskew M et al. . Patient retention from HIV diagnosis through one year on antiretroviral therapy at a primary health care clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62:e39–46. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318273ac48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan AS, Fielding KL, Thuo NM et al. . Early loss to follow-up of recently diagnosed HIV-infected adults from routine pre-ART care in a rural district hospital in Kenya: a cohort study. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:82–93. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02889.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honge BL, Jespersen S, Nordentoft PB et al. . Loss to follow-up occurs at all stages in the diagnostic and follow-up period among HIV-infected patients in Guinea-Bissau: a 7-year retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003499 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohler PK, Chung MH, McGrath CJ et al. . Implementation of free cotrimoxazole prophylaxis improves clinic retention among antiretroviral therapy-ineligible clients in Kenya. AIDS 2011;25:1657–61. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834957fd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P et al. . Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e13801 10.1371/journal.pone.0013801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Cooke GS et al. . Retention in HIV care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;56:e79–86. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182075ae2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namusobya J, Semitala FC, Amanyire G et al. . High retention in care among HIV-infected patients entering care with CD4 levels >350 cells/muL under routine program conditions in Uganda. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:1343–50. 10.1093/cid/cit490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pati R, Lahuerta M, Elul B et al. . Factors associated with loss to clinic among HIV patients not yet known to be eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Mozambique. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18490 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nwuba C, Livinus I, Okoye M et al. . Retention of pre-ART clients in care: impact of stage specific interventions. 7th IAS conference on HIV pathogenesis, treatment and prevention; 30 June–3 July 2013; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sialubanje C, Miyano S, Chipeta V et al. . Successfully enrolled in HIV care but not linked to timely treatment: poor retention and monitoring of pre-ART patients who are not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy. 16th International Conference on AIDS & STIs in Africa; 4–8 December 2011; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wettstein C, Mugglin C, Egger M et al. . Missed opportunities to prevent mother-to-child-transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2012;26:2361–73. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359ab0c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenthani L, Haas AD, Tweya H et al. . Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (‘Option B+’) in Malawi. AIDS 2014;28:589–98. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: a systematic review. AIDS 2012;26:2059–67. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283578b9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf (accessed 7 Jul 2014).

- 28.Volberding PA, Levine AM, Dieterich D et al. . Anemia in HIV infection: clinical impact and evidence-based management strategies. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:1454–63. 10.1086/383031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE et al. . Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;3:CD009756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N et al. . Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:942–51. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wynberg E, Cooke G, Shroufi A et al. . Impact of point-of-care CD4 testing on linkage to HIV care: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:18809 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mwai GW, Mburu G, Torpey K et al. . Role and outcomes of community health workers in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson BA, Schnippel K, Brennan A et al. . Same-day CD4 testing to improve uptake of HIV care and treatment in South Africa: point-of-care is not enough. AIDS Res Treat 2013;2013:941493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Tanser F et al. . Evaluation of the impact of immediate versus WHO recommendations-guided antiretroviral therapy initiation on HIV incidence: the ANRS 12249 TasP (Treatment as Prevention) trial in Hlabisa sub-district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:230 10.1186/1745-6215-14-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes R, Ayles H, Beyers N et al. . HPTN 071 (PopART): rationale and design of a cluster-randomised trial of the population impact of an HIV combination prevention intervention including universal testing and treatment—a study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials 2014;15:57 10.1186/1745-6215-15-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwuji C, Orne-Gliemann J, Tanser F et al. . Feasibility and acceptability of an antiretroviral treatment as prevention (TasP) intervention in rural South Africa: results from the ANRS 12249 TasP cluster-randomised trial. 20th International AIDS Conference; Melbourne; 20–25 July 2014 Abstract WEAC0105LB. [Google Scholar]