Abstract

Objectives

Cigarette price increases reduce smoking prevalence but as a tobacco control policy are undermined by the availability of lower cost alternatives such as hand-rolling tobacco. The aim of this descriptive study is to explore time trends in the price of manufactured cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco, and in the numbers of people who smoke these products, over recent years in the UK.

Settings and participants

UK.

Outcome measures

Trends in the most popular price category (MPPC) data for cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco from 1983 to 2012 adjusted for inflation using the Retail Price Index, and trends in smoking prevalence and the proportion of smokers using hand-rolling tobacco from 1974 to 2010.

Results

After adjustment for inflation, there was an increase in prices of manufactured cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco between 1983 and 2012. Between 1974 and 2010, the prevalence of smoking fell from 45% to 20%, and the estimated total number of smokers from 25.3 to 12.4 million. However the number of people smoking hand-rolling tobacco increased from 1.4 to 3.2 million, and MPPC cigarette price was strongly correlated with number of people smoking hand-rolling tobacco.

Conclusions

Although the ecological study design precludes conclusions on causality, the association between increases in manufactured cigarette price and the number of people smoking hand-rolling tobacco suggests that the lower cost of smoking hand-rolling tobacco encourages downtrading when cigarette prices rise. The magnitude of this association indicates that the lower cost of hand-rolling tobacco seriously undermines the use of price as a tobacco control measure.

Keywords: cigarette prices, hand rolling tobacco prices, smoking prevalence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to demonstrate the potential magnitude of the effect of cigarette price changes on the number of smokers choosing to use hand-rolling tobacco.

This is an ecological study—an observational study based on population-level estimates—and does not, therefore, establish causality in the relation between prices of cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco consumption.

Owing to the nature of the data sources used, it was not feasible to use more complex statistical methods that are more suitable for analysis of trends.

However, the findings provide grounds for more detailed investigation of this association.

Introduction

Preventing the burden of premature death and disability caused by smoking1 2 is global public health priority. The use of taxes to increase the price of tobacco products is a key policy to prevent smoking uptake, encourage quitting and reduce tobacco consumption,3 4 and appears to be particularly effective among the young and the socioeconomically disadvantaged.5–7 In particular, high prices discourage young people from purchasing cigarettes.8 Overall demand for tobacco is inelastic9 and it has been estimated that in Europe, a 10% price increase reduces cigarette consumption by approximately 5–7%.9–11 Price rises are thought to account for approximately one-third of the decline in smoking prevalence in the UK from 27% to 20% between 1998 and 2009.12 13

Successive UK governments have progressively increased taxes on cigarettes over recent decades, to the extent that retail cigarette prices in the UK are now among the highest in Europe.14 However, the metrics used to describe tobacco prices, such as the most popular price category (MPPC), and the recently introduced weighted average price (WAP) do not reflect the diversity of product prices on the market, some of which are substantially lower than the MPPC or WAP.15 Hence when prices increase, some cigarette smokers cut down or quit smoking in response, but others might compensate for price increases by switching or ‘downtrading’ to lower priced cigarette brands16 or to hand-rolling tobacco (HRT), which provides an even cheaper alternative for smokers.17

The availability of these lower priced alternatives, therefore, undermines the use of price as a prevention policy, but the extent to which downtrading occurs, particularly to HRT, has not been well defined in the UK or other markets. This study was carried out to explore the relation between cigarette prices and the number of people who smoke HRT using national UK price and smoking data.

Methods

UK MPPC price data for cigarettes (packs of 20) and HRT (25 g) were obtained for the years 1979–2012 and 1983–2012, respectively, from the Tobacco Manufacturers Association.18 Retail prices of individual brands of HRT were obtained from the monthly Price Checker supplement to the Retail Newsagent magazine,19 which published retail prices for the years 1995–2005 and is held for viewing at the British Library in Colindale. Two price figures were obtained for each product for each year, typically February and September. Continuous data were available for six HRT brands. We converted nominal prices into real prices using the monthly Retail Price Index (RPI) as a measure of inflation. The RPI was chosen over the Consumer Price Index, which is an alternative way for adjusting for inflation as RPI data were available for all years included in our analysis. We expressed all product prices in relation to real prices in March 2012.20

Male and female smoking prevalence, and the proportions of male and female smokers smoking HRT or cigarettes were taken for each year from 1974 to 2010 from the General Lifestyle Survey,21 as were data on the prevalence of cigarette and HRT smoking by age for 2010. Census data for England and Wales (for years 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001),22 scaled up to provide UK population estimates,23 were then interpolated between census years and combined with data on smoking prevalence and the proportion of smokers smoking HRT to generate estimates of the total number of smokers and the number smoking HRT in the UK, each year. Figures for the total amount of HRT consumed in the UK were also obtained from the Tobacco Manufacturers Association and were available for the years 1990–2009.18

All data were collated in a Microsoft Excel database (available as online supplementary appendix tables S1–S4), and analysed using STATA V.11, using simple descriptive statistics and correlation as appropriate.

Results

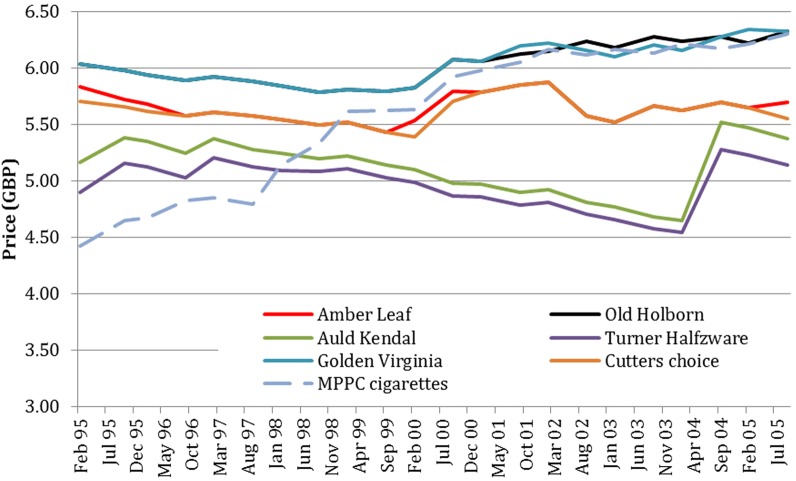

The MPPC prices of 20 cigarettes or 25 g HRT (equal to 33–42 cigarettes24 25), adjusted for inflation to 2012 levels, increased progressively between 1983 and 2012 (figure 1); however, this increase was more for cigarettes (from the equivalent of 3.15 GBP in 1983 to 7.47 GBP in 2012) than for HRT (from the equivalent of 4.46 GBP in 1983 to 8.12 GBP in 2012), that is, by 137% and 82%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Retail Price Index (RPI)-adjusted prices of most popular price category (MPPC) cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco (HRT), 1983–2012.

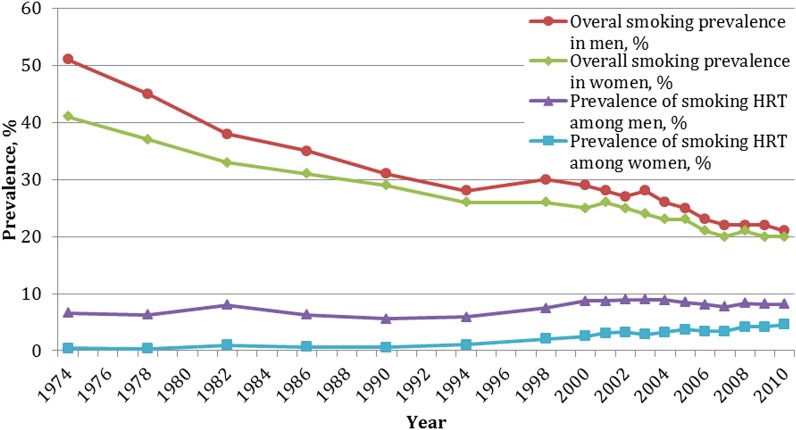

Of the individual HRT brands for which continuous data were available, adjusted prices of the two most expensive brands (Golden Virginia and Old Holborn) followed a similar pattern to the MPPC of cigarettes (indeed the HRT MPPC is thought to be based on the price of Golden Virginia), and over time, the price of a pack of these HRT brands remained similar to the MPPC cigarette price. Adjusted prices of Cutter's Choice and Amber Leaf, two slightly cheaper brands, remained relatively stable. The two cheapest brands, Turner Halfzware and Auld Kendall Mixed Medium Blend, showed a decrease in adjusted price between 1998 and 2004 despite consecutive annual budget increases in tax on HRT, before increasing substantially after February 2004 but still remaining lower in price than the other brands (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Retail Price Index (RPI)-adjusted Prices of specific hand-rolling tobacco (HRT) brands (25 g pack) and the most popular price category (MPPC) cigarettes (20 cigarettes) 1995–2005.

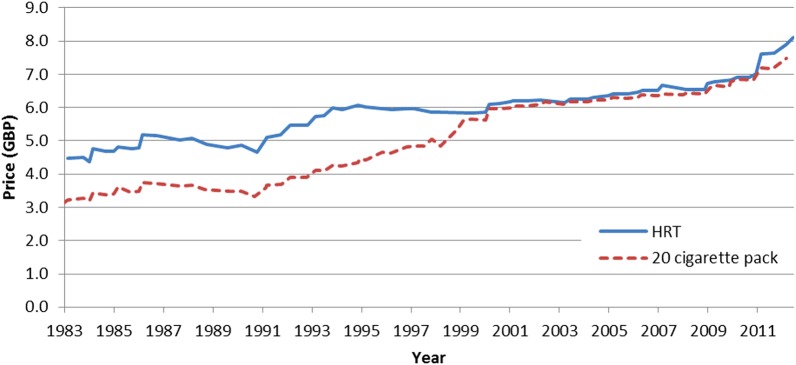

Although there was a sustained decline in smoking prevalence from 1974 to 2010 in both men and women (from 51% to 20% and from 41% to 20%, respectively) the proportion of the total population who smoke HRT increased slightly in men (from 6.6% to 8.2%), and from 0.4% to 4.6% in women (figure 3). However, the proportion of all smokers who use HRT increased considerably between 1974 and 2010, both among males and females (from 13% to 39%, and from 1% to 23%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Overall smoking prevalence and prevalence of smoking of hand-rolling tobacco (HRT) among men and women in Great Britain, 1974–2010.

The estimated number of people smoking any tobacco product also fell substantially between 1974 and 2010, from 25.3 to 12.4 million, while the number smoking HRT increased from 1.4 to 3.2 million, in part because of the increase in prevalence of HRT use among women, and in part because of UK's population growth. Total UK consumption of HRT also increased progressively, from 4170 ton in 1990 to 11 500 ton in 2009.

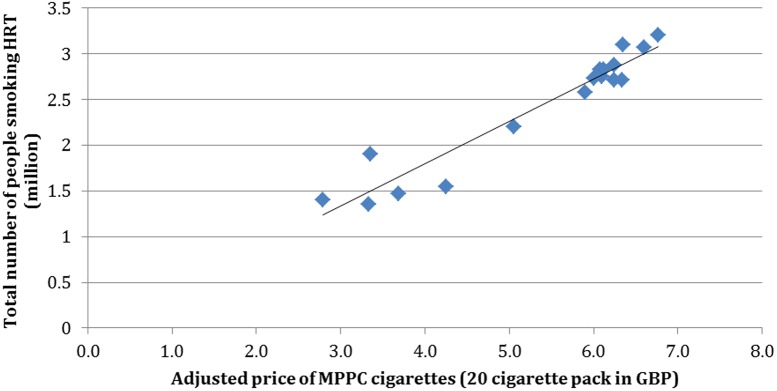

There was a strong correlation between the number of people smoking HRT and price of MPPC cigarettes (Spearman R=0.91; p<0.01, df=15; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of people smoking hand-rolling tobacco (HRT) and Retail Price Index (RPI)-adjusted most popular price category (MPPC) price of cigarettes, 1978–2010.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that over recent decades in the UK, the inflation-adjusted price of cigarettes has increased substantially, but the adjusted price of the less-expensive HRT products has remained relatively stable. During this period, the overall prevalence of smoking has fallen, but the proportion and number of smokers who smoke HRT, and the consumption of HRT, has increased markedly. We also found a strong correlation between MPPC cigarette prices and the total number of people using HRT. Although several factors could have contributed to the increased use of HRT, and the correlation between these variables in an observational study does not establish causation, our data are strongly consistent with the hypothesis that the marked price differential relative to manufactured cigarettes is an important driver of HRT use. While some of the previous research investigates changes and trends in HRT use over time in relation to tobacco prices in various countries,24 26 there is limited evidence on how HRT use is related to changes in cigarette prices in the UK. Previous research suggests that flat rates of HRT use can be explained by downtrading, by the fact that quit rates are lower among smokers of cheap tobacco products, and new smokers choosing to smoke HRT.27 Although increases in tobacco prices encourage smokers, and particularly those with low disposable incomes, to reduce or stop smoking,14 28–30 switching to HRT is a logical alternative for those unable or unwilling to quit. The effectiveness of price rises as a smoking prevention policy is, therefore, reduced substantially if smokers have an option to downtrade either to lower cost manufactured cigarettes,16 or to the even lower cost alternative of HRT.26 Although using more sophisticated analytical techniques, such as time series analysis, could provide a more detailed explanation of trends observed; such analysis was not feasible due to the relatively small number of data points available to us.

Results from this study are, however, in line with findings from a study carried out in Germany suggesting that an increase in price of manufactured cigarettes leads to an increase in consumption in HRT.26 Similarly, findings from studies in Italy also suggest that the proportion of HRT smokers has increased over time although overall smoking prevalence has decreased. During an economic downturn this effect was particularly strong in young men.24 31 Although a study from Ireland found no evidence of association between consumption of HRT and the price of manufactured cigarettes,32 it has been reported that an increase in income is significantly associated with reduced consumption of HRT, suggesting that HRT is viewed as a less desirable option by smokers.32

While the extent of downtrading to lower cost cigarettes in the UK has been documented previously,16 evidence on downtrading to HRT is limited. Although we cannot assume that all of the approximately one-third of a million UK smokers who started to use HRT per one pound increase in the MPPC price of a pack of 20 cigarettes would have quit smoking if the lower cost option of HRT had not been available to them, it is evident that the availability of HRT at such a significant price advantage relative to cigarettes is likely to have a major effect in perpetuating smoking. Switching to HRT may also suggest that many smokers view it as less harmful than manufactured cigarettes, and the lower levels of tax levied in the European Union (including the UK)32 supports this perception. As the net-of-tax component of the HRT price is higher than for cigarettes, the current tobacco price policy appears to encourage HRT consumption, as well as with conservative assumptions on the number of cigarettes that are typically rolled from a 25 g pouch of tobacco, probably generates higher income to the tobacco industry. In contrast to ultralow price cigarettes therefore, which are likely to be less profitable than other cigarettes but from a tobacco industry perspective do have the benefit of retaining customers, the availability of HRT at typical UK prices both perpetuates smoking and increases profits.

MPPC prices for HRT have been higher than those for cigarettes for all of the period of this study but, until very recently, have increased in parallel with the cigarette MPPC price and hence, in relative terms, become less expensive. Thus, in 1983, the HRT MPPC was about 50% higher than that of cigarettes, whereas by 2009 the difference was less than 20%; and in 2011, even after relatively large recent increases in tax on HRT specifically intended to prevent downtrading,33 the difference is only about 33%. Given the number of cigarettes that can be generated from 25 g of HRT, estimated to be 33–4224 25 to achieve price parity with a pack of 20 cigarettes will require the HRT price to be much higher than that of cigarettes. However, MPPC data do not represent typical prices of tobacco products on sale since the MPPC typically reflects prices of the most expensive brands. It appears from the individual brand data in this paper, and from cigarette brand prices reported elsewhere,16 that manufacturers manipulate prices across their product range to minimise the impact of tax increases on the lowest price products.16 If the effect of price increases as a tobacco control policy is to be maximised, it is essential that the increases apply similarly across all brands and that price differences between brands, including HRT, are minimised. Measures to reduce the availability of illicit HRT at even lower prices are also essential.

Overall our findings suggest that the effects of tobacco tax increases, which are a key component of tobacco control policy in the UK, are being undermined substantially by price differentials between different types of tobacco, and indeed between different brands. The UK government, therefore, needs to consider measures to increase the price of cigarettes and HRT to generate parity of cost per cigarette, and the taking of more robust measures to reduce the availability of low-price tobacco to smokers.

Footnotes

Contributors: LR collected and analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JB was involved in designing the study, collecting the data, and interpreting the findings, and also helped in drafting of the manuscript. IB contributed to data collection and analysis, and was involved in drafting of the manuscript and interpreting the findings. All the authors contributed to the final manuscript and have approved its publication.

Funding: The work was undertaken by the UK Centre for Tobacco & Alcohol Studies, a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. www.esrc.ac.uk/publichealthresearchcentres

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data included in the study are available to public from sources indicated in the paper and authors can provide more information on request; we have also provided data used for this study as a supplementary document.

References

- 1.Mortality attributable to tobacco. Secondary Mortality attributable to tobacco 2004. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/fact_sheet_mortality_report.pdf Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6FyDE02XE

- 2.Smoking and tobacco use health effects. Secondary Smoking and tobacco use health effects 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/health_effects/index.htm Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6FwuxOfPN

- 3. Guidelines for implementation of Article 6 of the WHO FCTC: World Health Organization, 2011. http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/Guidelines_article_6.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2015).

- 4.Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med 2014;370:60–8. 10.1056/NEJMra1308383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fayter D, Main C, Misso K et al. . Population tobacco control interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, 2008. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/CRD_Reports/crdreport39.pdf (accessed 10 Oct 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostova D, Ross H, Blecher E et al. . Is youth smoking responsive to cigarette prices? Evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Tob Control 2011;20:419–24. 10.1136/tc.2010.038786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 2011;20:235–8. 10.1136/tc.2010.039982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce JP, White VM, Emery SL. What public health strategies are needed to reduce smoking initiation? Tob Control 2012;21:258–64. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control, Vol.14: Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control (2011:Lyon, France). http://w2.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/prev/handbook14/handbook14.pdf (accessed 6 Nov 2014).

- 10.Gallus S, Schiaffino A, La Vecchia C et al. . Price and cigarette consumption in Europe. Tob Control 2006;15:114–19. 10.1136/tc.2005.012468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kostova D, Tesche J, Perucic AM et al. . Exploring the relationship between cigarette prices and smoking among adults: a cross-country study of low- and middle-income nations. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16(Suppl 1):S10–15. 10.1093/ntr/ntt170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapter 1—Smoking (General Lifestyle Survey Overview—a report on the 2011 General Lifestyle Survey), Office for National Statistics. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_302558.pdf (accessed 6 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy DT, Currie L, Clancy L. Tobacco control policy in the UK: blueprint for the rest of Europe? Eur J Public Health 2013;23:201–6. 10.1093/eurpub/cks090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogdanovica I, Murray R, McNeill A et al. . Cigarette price, affordability and smoking prevalence in the European Union. Addiction 2012;107:188–96. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03588.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spanopoulos D, Ratschen E, McNeill A et al. . Retail price and point of sale display of tobacco in the UK: a descriptive study of small retailers. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e29871 10.1371/journal.pone.0029871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilmore AB, Tavakoly B, Taylor G et al. . Understanding tobacco industry pricing strategy and whether it undermines tobacco tax policy: the example of the UK cigarette market. Addiction 2013;108:1317–26. 10.1111/add.12159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Granda-Orive JI, Jiménez-Ruiz CA. Some thoughts on hand-rolled cigarette. Arch Bronconeumol 2011;47:425–6. 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association. Secondary Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association 2010. http://www.the-tma.org.uk/ Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Fy906dv1

- 19. Newtrade. Retail Newsagent. Secondary Retail Newsagent 2012. http://newtrade.co.uk/our-products/print/retail-newsagent/ Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6FwxJULtE.

- 20.Office for National Statistics—Retail Price Index. http://ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Retail+Prices+Index (accessed 16 Jan 2015).

- 21.General Lifestyle survey 2010. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ghs/general-lifestyle-survey/2010/index.html Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Fy5yh01m [Google Scholar]

- 22. 100 years of census: England and Wales 1911–2011. Secondary 100 years of census: England and Wales 1911–2011, 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/interactive/vp1-story-of-the-census/index.html Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Fy66gkJU.

- 23. Population, total. Secondary Population, total 2012. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6FwukpEPm.

- 24.Gallus S, Lugo A, Colombo P et al. . Smoking prevalence in Italy 2011 and 2012, with a focus on hand-rolled cigarettes. Prev Med 2013;56:314–18. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Nicolas A, Belen Cobacho M, Fernandez E. The Spanish tobacco tax loopholes and their consequences. Tob Control 2013;22:e21–4. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanewinkel R, Radden C, Rosenkranz T. Price increase causes fewer sales of factory-made cigarettes and higher sales of cheaper loose tobacco in Germany. Health Econ 2008;17:683–93. 10.1002/hec.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore AB, Tavakoly B, Hiscock R et al. . Smoking patterns in Great Britain: the rise of cheap cigarette brands and roll your own (RYO) tobacco. J Public Health (Oxf) 2015;37:78–88. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reducing Tobacco Use: A report for the Surgeon General. Secondary Reducing Tobacco Use: A report for the Surgeon General 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2000/complete_report/pdfs/fullreport.pdf Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Fy5ku5Sy.

- 29.Townsend J. Price and consumption of tobacco. Br Med Bull 1996;52:132–42. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Decrease in smoking prevalence—Minnesota, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:138–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallus S, Spizzichino L, Lugo A et al. . Sales of different tobacco products in Italy, 2004–2012. Prev Med 2013;56:422–3. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornelsen L, Normand C. Is roll-your-own tobacco substitute for manufactured cigarettes: evidence from Ireland? J Public Health (Oxf) 2014;36:65–71. 10.1093/pubmed/fdt030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobacco Products Rates of Duty. Secondary Tobacco Products Rates of Duty 2011. http://www.hmrc.gov.uk/budget2011/tiin6345.pdf Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Fwx6zHIW [Google Scholar]