Abstract

Objectives

This paper reviews the current state of the published peer-reviewed literature related to return-to-work (RTW) interventions that incorporate work-related problem-solving skills for workers with sickness absences related to mental disorders. It addresses the question: What is the evidence for the effectiveness of these RTW interventions?

Design

Using a multiphase screening process, this systematic literature review was based on publically available peer-reviewed studies. Five electronic databases were searched: (1) Medline Current, (2) Medline In-process, (3) PsycINFO, (4) Econlit and (5) Web of Science.

Setting

The focus was on RTW interventions for workers with medically certified sickness absences related to mental disorders.

Participants

Workers with medically certified sickness absences related to mental disorders.

Interventions

RTW intervention included work-focused problem-solving skills.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

RTW rates and length of sickness absences.

Results

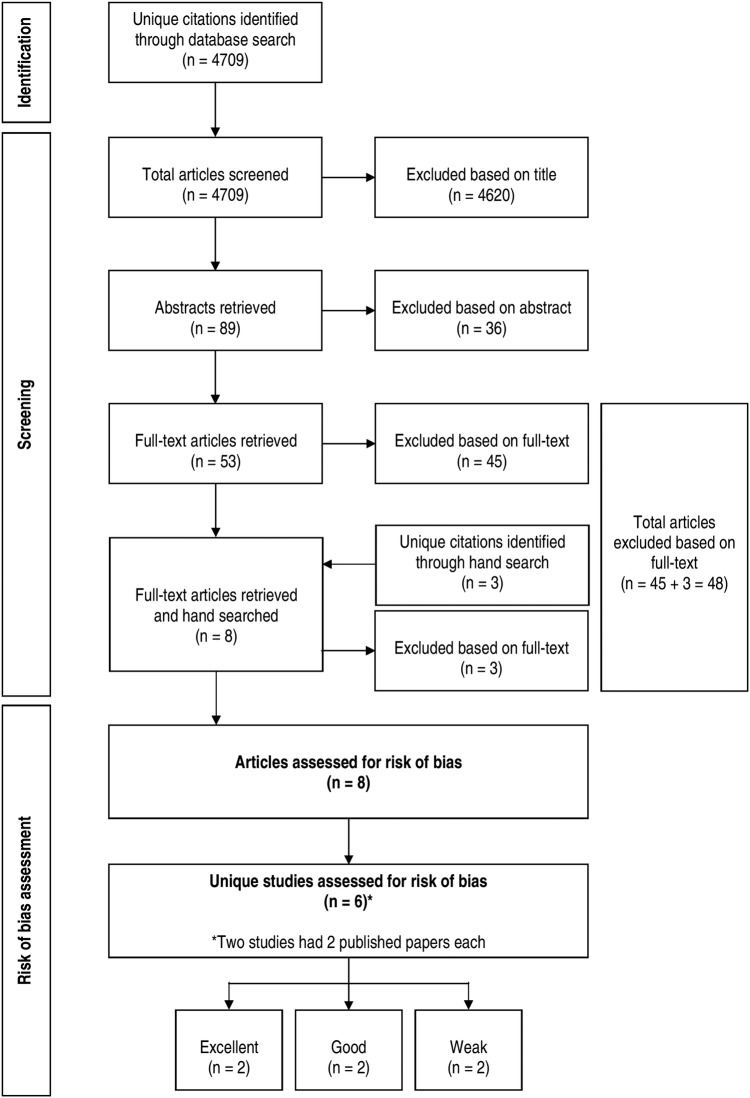

There were 4709 unique citations identified. Of these, eight articles representing a total of six studies were included in the review. In terms of bias avoidance, two of the six studies were rated as excellent, two as good and two as weak. Five studies were from the Netherlands; one was from Norway. There was variability among the studies with regard to RTW findings. Two of three studies reported significant differences in RTW rates between the intervention and control groups. One of six studies observed a significant difference in sickness absence duration between intervention and control groups.

Conclusions

There is limited evidence that combinations of interventions that include work-related problem-solving skills are effective in RTW outcomes. The evidence could be strengthened if future studies included more detailed examinations of intervention adherence and changes in problem-solving skills. Future studies should also examine the long-term effects of problem-solving skills on sickness absence recurrence and work productivity.

Keywords: work disability, mental disorders, return-to-work, sickness absence, problem-solving, interventions

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Few studies have examined the current state of knowledge about the effectiveness of incorporating work-related problem-solving skills into return-to-work interventions.

This systematic literature review employed a broad search of five electronic databases: (1) Medline Current, (2) Medline In-process, (3) PsycINFO, (4) Econlit and (5) Web of Science. A manual search was also conducted. In total, 4709 unique citations were identified and reviewed by two reviewers.

All included studies used randomised controlled trial designs.

The results of the search identified eight papers that represented six studies that met the inclusion criteria; this suggests that we are in the early stages of understanding the contribution of work-focused problem-solving skills in RTW interventions.

There was variability among the identified studies with respect to inclusion criteria and intervention adherence monitoring, and measurement of intermediate outcomes (ie, improvement in problem-solving skills).

One of the major burdens of mental disorders1–3 is related to work productivity losses such as work absences.4 One of the most costly forms of work absences is associated with mental illness-related work disability leave.5

Consequently, there has been growing interest in occupational stress management programmes.6 7 Indeed, there is evidence suggesting that chronic high stress can interact with mental disorders to magnify the risk of disability.8 Ivancevich et al9 describe three potential foci for stress management programmes: the worker, the workplace, and both the worker and workplace. In addition, these programmes can target three points in the stress cycle by: (1) changing the degree of stress (ie, by decreasing the intensity or number of stressors), (2) helping workers to modify how they perceive stressors, and (3) helping workers gain skills to cope effectively with stress.9

Of the three potential intervention points, attention has been on the latter two. Coping theory suggests that there are two major types of coping approaches: problem-focused and emotion-focused (ie, reactive-passive).10 The former of these two types of coping styles has been observed to be significantly associated with decreased sickness absences.11 Examples of problem-focused coping include problem-solving therapies.12

During the last decade, there has been an increase in the number of studies that have examined the effectiveness of interventions that incorporate teaching new skills to workers who are receiving disability benefits. These skills are aimed at enabling them to solve work-related problems. Evidence suggests that these skills help to develop a sense of control regarding stressors. In turn, this can moderate the effects of work stressors that could contribute to disability and ill health.13 In addition, the results of a meta-analysis indicate that problem-solving therapy can be effective in treating people with depression.12

The purpose of this study is to review the current state of the published peer-reviewed literature related to return-to-work (RTW) interventions that incorporate work-focused problem-solving skills for workers. Through a systematic literature review, we seek to answer the question, “What is the evidence for the effectiveness of RTW interventions that have incorporated work-focused problem-solving interventions for workers who have a sickness absence related to a mental disorder?” Based on a recent systematic review of sickness absence outcomes, for this review, effectiveness was defined in terms of two sickness absence outcomes: (1) whether and (2) how long it took for a worker to RTW.14 Answers to these questions can help to interpret the current state of knowledge as well as to highlight gaps in the literature and areas for future exploration.

Methods

This systematic literature review used publically available peer-reviewed studies. It did not involve the collection or the use of primary data. Thus, it was not subject to research ethics board review.

Five electronic databases were searched: (1) Medline Current (an index of biomedical research and clinical sciences journal articles), (2) Medline In-process (an index of biomedical research and clinical sciences journal articles awaiting indexing into Medline Current), (3) PsycINFO (an index of journal articles, books, chapters, and dissertations in psychology, social sciences, behavioral sciences, and health sciences), (4) Econlit (an index of journal articles, books, working papers and dissertations in Economics), and (5) Web of Science (an index of journal articles, editorially selected books and conference proceedings in life sciences and biomedical research). The OVID platform was used to search Medline Current, Medline In-process and PsychINFO. Econlit and Web of Science were searched using the ProQuest and Thomson Reuters search interface, respectively. The reference lists of relevant studies and systematic reviews were also hand searched.

Search strategies were developed and refined in collaboration with a professional health science librarian (SB) (see online supplementary file 1: search strategy). Searches were completed between February 2014 and July 2014. All search results were limited to English language journals published between 2002 and 2014.

The year 2002 was used as an inclusion starting point because in their review of 20 countries, including the Netherlands, Norway and the UK, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) concluded that the 1990s were a period during which there was a global change in disability policy.15 For example, the Netherlands introduced the Sickness Absence (Reduction) Act and an amendment to the Working Conditions Act in 1994 and instituted the Gatekeeper Improvement Act in 2002. These laws were intended to increase employer and employee responsibilities in reducing sickness absence due to illness. In addition, in 2000, the European Union Council Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 was issued that established a framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation.15 One of its goals was to decrease discrimination against workers with specific medical disorders such as mental illnesses. Thus, there was emphasis to prevent people from taking disability leave and leaving the labour market.

In addition, as we sought to account for the publication lag, we included studies based on data that were conducted in 2000 or later. Thus, studies using pre-2000 data were excluded because pre-2000 data were collected within systems that existed before many of the policy changes in the 1990s.

Eligibility criteria

Our systematic literature search focused on RTW interventions for workers with medically certified sickness absences related to mental disorders. For the purposes of this review, sickness absence included sick leave, short-term disability leave and long-term disability leave. Sickness absence benefits could be either publicly or privately sponsored. However, receipt of these benefits had to be conditional on employment and claimed with the intention of continued employment. Studies that looked at ‘no cause’ sickness absences were included and absence was not required to be work-related. RTW interventions were defined as any programme with prescribed activities with the objective of having employees return to their pre-absence workplaces.

A multiphase screening process was used to identify relevant articles; two reviewers (CSD and DL) completed the screening. The first phase involved title screening for relevance. Articles that passed the first phase were then evaluated for relevance based on their abstracts. Those that passed the abstract screening phase were then evaluated for content relevancy based on a full-text review. The inter-rater reliability corrected for chance agreement was κ=0.82. In the case of rater disagreements, the articles were discussed until consensus was reached. Consensus regarding the inclusion of the final articles was reached among CSD, DL and MJ.

The following eligibility criteria were used in each phase:

The study sample was comprised of workers on medically certified sickness absences due to mental disorders;

The evaluated intervention included work-focused problem-solving skills;

The study assessed effectiveness in terms of RTW outcomes (ie, whether and how long it took for a worker to RTW).

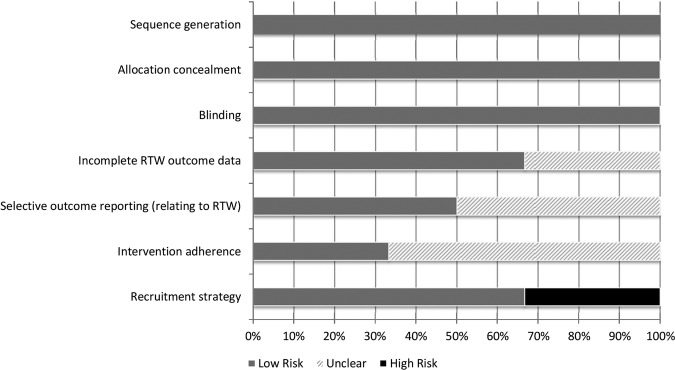

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias was assessed using the guidelines suggested by the ‘Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions’.16 Seven items were considered: (1) adequate sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding, (4) incomplete RTW outcome data, (5) selective reporting, (6) intervention adherence, and (7) recruitment strategy. If a study had a protocol that was published, information from the published protocol was also reviewed.

Each of the 7 items were scored separately on a three-point scale such that 1=low risk of bias, 0=unclear (ie, there was insufficient information about the study to determine whether there was either a high or low risk of bias), and −1=high risk of bias.

We also calculated a summary score of all the items; the maximum score was 7. Total scores between 1 and 3 points were categorised as weak quality, those between 4 and 5 points were good, and those between 6 and 7 points were excellent quality.

Results

Inclusion and exclusion

The electronic literature search resulted in the identification of 4709 unique citations (figure 1). Based on the title review, 4620 citations were excluded; this left 89 articles for abstract review. During the abstract review, another 36 citations were excluded; this left 53 articles for full-text review. After the full-text review, 8 articles remained and their reference lists were hand searched for relevant studies. The hand search identified three additional citations. However, all were excluded at full text review. Reasons for article exclusions were because: (1) a RTW programme that incorporated work-focused problem-solving skills was not evaluated (n=34), (2) the study population was not relevant (n=7), (3) it was a literature review (n=2), and (4) a RTW outcome was not assessed (n=5).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search results and inclusions/exclusions. RTW, return-to-work

Bias risk assessment

The eight articles represented a total of six studies. In terms of potential bias avoidance, our assessment identified two of the six studies as excellent, two as good and two as weak. Figure 2 shows the areas of potential bias of these studies. All the studies were randomised controlled trials in which the researchers were blinded with respect to the assignment (see online supplementary file 2: risk assessment of bias checklist). Thus, all had low risk of bias related to sequence generation, allocation concealment, and outcome assessment. However, for three studies, there were less details regarding the characteristics of the sample that either dropped out or had missing data compared with the final sample population. For the studies that did not have a protocol (n=3), it was also difficult to discern whether there was selective outcome reporting. Four of the studies did not indicate whether there was a check for intervention adherence during the study. Finally, for two of the studies, the described recruitment strategies seemed to rely on provider referrals; this would have exposed the selection of the study population to selection bias by the provider.

Figure 2.

Summary of risk assessment of bias.

Overview of the studies

There were six studies (eight published articles) that met the inclusion criteria. Except for one from Norway, five studies were from the Netherlands (table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptions of RTW intervention studies

| Author(s) | Intervention(s) | Study population | Study design data points | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| van der Klink et al20 The Netherlands |

Problem-solving intervention+graded activity vs care as usual Intervention delivered by an OP:

|

n=192 patients Postal and Telecom Services Included: on sick leave for 2 weeks, DSM-IV adjustment disorder, last 3 m adjustment disorder with identifiable stressor, 8 of 17 distress symptoms meeting DSM criteria, 1st sickness absence due to adjustment disorder Excluded: Did not have an adjustment disorder, had a physical comorbidity, treated for adjustment disorder in the previous year |

Study design: Cluster randomised controlled trial Data points: BL, 12, 52 weeks |

Outcomes:

|

| Brouwers et al21

22 The Netherlands |

Intervention similar to van der Klink et al20 Aimed at activating and supporting patient to restore coping and to adopt a problem-solving approach and return to work as soon as possible Social worker provided:

|

n=194 Recruited by 70 GPs August 2001 and July 2003 Included: suffering from emotional distress or minor mental disorders based on GP and self-report, on paid employment, on sick leave for <3 m, 18–60 years Excluded: Severe mood or anxiety disorder as confirmed by CIDI |

Study design: RCT Data points: BL, 3, 6 and 18 m |

Outcomes:

|

| Hees et al25

26 The Netherlands |

Adjuvant occupational therapy vs care as usual Adjuvant occupational therapy:

|

n=117 Referred by OPs Participants: December 2007–October 2009 Included: working at least 2 h/week, 18–65 years, MDD, absent from work for at least 25% of contract hours due to depression, duration of absence at least 8 weeks or MDD duration of 3 m, relationship between work and MDD Excluded: severe alcohol or drug dependence, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, depression with psychotic characteristics, inpatient treatment |

Study Design: RCT Data points: BL, 6, 12, 18 m |

Outcomes:

|

| Nystuen and Hagen27 Norway |

Solution focused follow-up vs treatment as usual Intervention delivered by psychologists:

|

n=106 All people from two social security offices meeting inclusion criteria were included in the study Included: sick listed for >7 weeks due to non-severe psychological problems (ICPC—chapter P), general exhaustion and burnout (ICPC: A01, A04) or muscle skeletal pain (ICPC—chapter L) excluded: serious psychological diagnoses (ICPC: P70-73, P77, P80, P98), muscle skeletal pain (ICPC: L70, L71, L72-L76, L77-L79, L80-82) |

Study Design: RCT Data points: BL, end of sick leave |

Outcome:

|

| Rebergen et al17–19 The Netherlands |

GBC vs care as usual GBC delivered by an OP:

|

n=240 January 2002-January 2005 Police force employees Included: Workers who consulted an OP and still on sick leave due to mental illness in January 2002 |

Study design: RCT Follow-up: 1 year |

Outcomes:

|

| Vlasvled et al23

24 The Netherlands |

Collaborative care vs care as usual Collaborative care:

|

n=126 Occupational health service Included: sickness absence between 4 and 12 weeks, Diagnosis of depression by OP |

Study design: RCTData points: BL, 3, 6, 9, 12 m | Outcomes:

|

APA, American Psychiatric Association; BL, baseline; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; GBC, guideline-based care; GP, general practitioners; ICPC, International Classification of Primary Care; m, months; MDD, major depressive disorder; OP, occupational physician; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RTW, return-to-work.

Description of the study populations and participants

The included studies recruited participants from a number of sources. Two of the studies recruited potential participants from specific business sectors—police17–19 and postal and telecom.20 Three studies used treatment and social service providers such as general practitioners (GPs),21 22 occupational health services,23 24 occupational physicians (OPs)25 26 and social security offices.27

Diagnoses

All of the studies included only workers who were on medically certified sickness absences related to mental disorders. However, there was variability among the studies with respect to the mental disorders to which the absences were attributed. The studies were also spilt according to the severity of the disorders. Three studies sought to exclude participants with severe mental disorders.20 21 27 In contrast, two of the studies focused on participants with depressive disorders.23–26 One study included participants with any common mental disorder.17 18

Of the three studies that focused on non-severe mental disorders, one study recruited workers with minor mental disorders;21 based on the CIDI, these participants had mild depressive disorders, dysthymia and mild bipolar disorder. Another study included only participants with medically diagnosed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) adjustments disorders.20 A third included only participants with psychological distress, symptoms of general exhaustion or burnout as diagnosed using the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC).27

Of the three studies that did not systematically exclude severe mental disorders, two included only workers with depression based on DSM-IV criteria.23–26 The third study included all mental disorders.17 18

Interventions and comparison groups

There was variation among the studies in terms of how work-focused problem-solving interventions were incorporated. For example, both the van der Klink et al20 and Brouwers et al21 studies looked at a problem-solving intervention combined with graded activity. However, the comparison groups for the two studies potentially received different treatments. van der Klink et al's20 care as usual included empathic counselling and discussion of work problems with the worker and company management. In contrast, Brouwers et al's21 care as usual was treatment received from the worker's GP.

The problem-solving skills in Hees et al's25 26 intervention were provided by an occupational therapist (OT) as part of nine individual and nine group sessions; the OT consulted with the OP and treating psychiatrist during the intervention. Usual care was treatment provided by a psychiatric resident in an outpatient clinic.

In Rebergen et al's17 18 study, the problem-solving intervention was a component of guideline-based care provided by OPs who received training in the guidelines. Based on the care guidelines, OP treatment had to include a time-contingent process evaluation, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)-based therapy, problem-solving skills at work, gradual RTW and regular supervisor contact. The comparison OPs were not trained in the guideline use and referred workers to psychologists for additional treatment as usual.

Vlasveld et al23 24 examined the effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention in which the OP was the case manager and there was collaboration with a consulting psychiatrist, workplace and the worker. The OP provided 6–12 sessions of a standardised problem-solving treatment; the worker was also given a guided self-help manual. There was also a workplace intervention in which the worker, manager and OT participated. The comparison group received care from OP, GP and mental health specialists; all the providers were accessed independently and they did not collaborate in service provision.

In Nystuen and Hagen's27 study, the problem-solving intervention was delivered by three psychologists in both the individual and group situations. There were also eight group sessions that focused on coping strategies. The comparison group received care as usual that included written information from the social security office.

RTW outcomes

The two main RTW outcomes that were of interest were: (1) whether a worker returned-to-work (RTW rates) and (2) duration of sickness absence. RTW was defined in a variety of ways including time to full RTW, partial RTW and any RTW (table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes of RTW intervention studies

| Author(s) | Intervention(s) | RTW* | Sickness leave duration* |

|---|---|---|---|

| van der Klink et al20 The Netherlands |

Problem-solving intervention+graded activity vs care as usual | % RTW (cluster level analysis): 3 m (partial or full): 98% vs 87%; p=0.01 Full RTW: 3 m: 79% vs 64%; p=0.08 Full RTW: 12 m: 100% vs 100% |

Cluster level: RTW (in days) Median: 37 (95% CI 32 to 42) vs 51 (95% CI 35 to 67) Mean: 36 (95% CI 31 to 40) vs 53 (95% CI 44 to 62); p=0.00 Full RTW (in days) Median: 60 (95% CI 52 to 67) vs 83 (95% CI 79 to 88) Mean: 67 (95% CI 52 to 83) vs 94 (95% CI 71 to 117): p=0.10 Duration of sick leave (in days): Median: 46 (95% CI 41 to 51) vs 67 (95% CI 40 to 94) Mean: 49 (95% CI 40 to 58) vs 73 (95% CI 55 to 92); p=0.02 |

| Brouwers et al21 The Netherlands |

Intervention similar to van der Klink et al20 | % Partial RTW: no significant differences 3 m: 27.8% vs 23.9% 6 m: 23.1% vs 23.5% 18 m: 5.7% vs 7.9% % Full RTW: no significant differences 3 m: 37.1% vs 39.8% 6 m: 58.2% vs 62.4% 18 m: 85.1% vs 77.6% |

Sick leave (in days): Mean: 106 (SD=87) vs 121 (SD=94) Median: 86 vs 100 Full RTW (in days): Mean: 153 (SD=122) vs 157 (SD=121) Median: 120 vs 119 No significant differences in work resumption over time |

| Hees et al26 The Netherlands |

Adjuvant occupational therapy vs care as usual | % RTW in good health: 6 m: 6% vs 10%; adjusted effect=−1% (95% CI −8% to 6%) 12 m: 34% vs 23%; adjusted effect=8% (95% CI −3% to 20%) 18 m: 52% vs 28%; adjusted effect=24% (95% CI 12% to 36%) Coefficients from mixed model: Group: 0.03 (95% CI −0.8 to 0.9); p=0.94 Time: 1.2 (95% CI 0.8 to 1.5); p<0.001 Time2: −0.5 (95% CI −1.0 to −0.1); p=0.01 Group×time: 0.6 (95% CI 0.1 to 1.5); p=0.02 Group×time2: −0.3 (95% CI −1.1 to 0.6); p=0.49 |

Mean Absenteeism (in hours): 6 m: 22.7 (SD=10.0) vs 23.3 (SD=10.8) 12 m: 14.1 (SD=11.9) vs 17.0 (SD=12.8) 18 m: 10.4 (SD=12.5) vs 11.9 (SD=12.3) Coefficients from mixed model: Group: −5.5 (95% CI −22.9 to 11.9); p=0.53 Time: −36.0 (95% CI −42.2 to −29.8); p<0.001 Time2: 10.9 (95% CI 4.7 to 17.0); p<0.001 Group×time: −3.1 (95% CI −16.2 to 10.4); p=0.64 Group×time2: 11.0 (95% CI −1.9 to 23.8); p=0.09 Median partial RTW (in days): 80 (IQR: 42, 172) vs 166 (IQR: 67, 350) HR=0.72; p=0.14 Median full RTW (in days): 361 (IQR: 193, 653) vs 405 (IQR: 189, 613) HR=0.93; p=0.79 |

| Nystuen and Hagen27 Norway |

Solution focused follow-up vs treatment as usual | Mean days: 217.5 (SD=82.8) vs 212.0 (SD=84.2); p=0.73 | |

| Rebergen et al17 The Netherlands |

Guideline based care vs care as usual | Partial RTW (in days): Mean: 53.1 (SD=56.3) vs 50.6 (SD=78.4); p=0.28 Median: 50 (95% CI 34 to 66) vs 47 (95% CI 31 to 63) HR=0.99; p=0.94 Full RTW (in days): Median: 105 (95% CI 84 to 126) vs 104 (95% CI 81 to 127) HR=0.96; p=0.78 |

|

| Vlasvled et al23 The Netherlands |

Collaborative care vs care as usual | Full RTW: 12 m: 64.6% vs 59.0% (not tested) | Full RTW (mean days): 198 (SD=120) vs 215 (SD=118); p>0.05 |

*Intervention vs control.

m, months; RTW, return-to-work.

RTW rates

Three studies examined RTW rates. The data collection points varied among the studies as did the findings. For example, at 3 months van der Klink et al20 observed significant differences between the invention and control groups (98% vs 87%, respectively) with respect to any RTW. However, the differences were not significant in terms of full RTW. Furthermore, differences were not significant at 12 months because the entire sample returned to work.

Hees et al26 quality adjusted the RTW measure for full RTW and remission of depression symptoms. They noted significant differences between the intervention and control groups over time (ie, between baseline and 18 months).

In contrast to the previous two studies, Brouwers et al21 did not observe significant differences between the intervention and control groups with regard to either full or partial RTW at 3, 6 or 18 months.

Duration of sickness absence

All six of the studies looked at the duration of sickness absence. The studies differed in the time period they examined; these periods included time to full RTW, partial RTW, any RTW as well as absenteeism. Only one study found a significant difference between the intervention and control groups. van der Klink et al20 reported significant differences in RTW for the intervention (36 days, 95% CI 31 to 40) versus the control group (53 days, 95% CI 44 to 62).

Discussion

This systematic literature review examined the evidence for the effectiveness of the incorporation of work-focused problem-solving skills in RTW interventions. Six studies were identified that incorporated work-focused problem-solving as part of its RTW intervention. The study by van der Klink et al20 appears to be the starting point of much of this literature. Thus, five of the six studies were conducted in the Netherlands; one was conducted in Norway. There was equivocal evidence with regard to RTW rates and the duration of sickness absence.

These equivocal results may be related to the variation in the studies. For example, among the six studies, there was variation in the way that skills were delivered, including individual and group sessions. In addition, in these studies, work-focused problem-solving skills training were most often combined with other activities such as coping skills, a workplace intervention, counselling and therapy.

Variation in risk of bias

The bias avoidance assessment suggested there was variability in the extent to which bias was avoided; our assessment identified two of the six studies as excellent, two as good and two as weak. Part of the variation could be attributed to the lack of details provided in the papers. There was also potential bias introduced by the recruitment strategies used to identify potential study participants. That is, all the studies used randomisation once participants were identified. However, the extent of the results’ generalisability is not clear because there is insufficient information about the population from which these were drawn (ie, were providers biased with regard to whom they referred). One way this could have been addressed was by providing more details about the characteristics of the pool from which each of the providers were selecting referrals.

Adherence to the intervention

In addition, there was a lack of information about adherence to the intervention. Thus, there is a question about the extent to which the non-significant results are related to the quality and consistency of the delivery of the intervention. While adherence may be difficult to track or measure, this challenge in part might be addressed by determining whether the intervention group experiences significant changes in problem-solving or coping. That is, the question that would need to be answered is, “Does the problem-solving intervention enhance problem-solving or coping ability?” This type of intermediate outcome would also help to understand whether the problem-solving component was effective. For example, Hees et al26 reported a significant change over time with respect to active problem-solving skills, avoidance and passive reaction. However, the changes between the treatment and intervention groups were not significant. This raises the question of whether symptoms hinder problem-solving skills versus whether untaught problem-solving skills were a factor that contributed to disability.

When van der Klink et al20 monitored intervention adherence and included a measure of skill mastery, they did not find a significant difference between the intervention and control groups with respect to skill mastery. They also included a measure of coping; however, these results were not reported. Yet, information about the intermediate outcomes (ie, coping) would help in understanding how the intervention is working.

Variability in the comparison group

There was also variability in what was considered usual care. Depending on the study, usual care could be counselling, GP visits, psychologist visits, psychiatrist visits or social security office literature. This leads to a question of whether the non-significant differences were related to the chosen comparison. At the same time, one study that offered specialised mental health services20 23 to the control group also observed a significant difference between the comparison and intervention groups. On one hand, these results suggest that standard treatment may not be sufficient to address work disability. On the other hand, this study also monitored adherence to the intervention. It is difficult to distinguish the effect of the intervention from the monitoring.

Variability in diagnoses

One of the studies that reported positive and significant differences in favour of the intervention sought to exclude participants with severe mental disorders.20 In addition, two of the studies which focused on participants with depressive disorders.23 26 This raises the question of the appropriate target population for this intervention. Should it be workers with more or less severe disorders? There is also the question of timing. At what phase in an episode of mental illness should the problem-solving intervention be introduced? Unlike most of the other studies that focused on non-severe mental disorders at early stages, Hees et al26 limited participants to workers who were absent for at least 8 weeks or had depression for at least 3 months. They reported that workers in the intervention were significantly more likely to RTW in good health. This finding may suggest that this type of intervention is effective at later phases of the episodes of mental illness.

Future research directions

The results of this systematic review also point out whether there are opportunities to extend this literature. For example, it is not clear whether it is necessary to teach coping and problem-solving skills to everyone returning from sickness absence. One way to approach this question is to determine whether there is an optimal amount of work-related problem-solving skills.

Once a threshold is identified, it will be important for future studies to report results of intermediate outcomes such as changes in work-related problem-solving ability. This information will help to determine the effectiveness of interventions in producing a work-significant improvement in skill. This line of inquiry will also necessitate understanding how problem-solving skills are used at work and whether there are differences by occupation.

Greater details regarding adherence to problem-solving interventions could also help to direct future research. It would be useful to understand how long adherence to the intervention lasts. Is there an optimal length of time and intensity for training to have long-term effects? Are adaptations to skill training interventions necessary depending on the type of disorders?

There is also the question about the most effective point during the sickness absence to begin to learn these problem-solving skills. Future studies should also examine the long-term effects of problem-solving on sickness absence recurrence and work productivity. This will advance understanding about whether the tools learned during sickness absence can be a protective factor in recurrence of sickness absence. In a recent study, Arends et al28 observed significant differences in recurrence of sickness absence with a problem-solving intervention. As they point out, future work could look at the effectiveness of booster training. In addition, it would be useful to investigate the characteristics of workers for whom this could be used as a targeted intervention.

Strengths and limitations of the search strategy

Although we used five databases in our search, we would have overlooked articles that did not appear in any of the searched databases. We sought to minimise this possibility by employing a broad scope for each of the database searches and also hand searched reference lists of relevant articles.

Another limitation is related to the fact that the search focused on articles published in English-language journals. Despite the English-language constraint, the identified studies originated in Europe. This indicates that although they are not in countries where English is the first language, at least some of these researchers publish in English-language journals.

Conclusions

There is an emerging literature regarding the effectiveness of interventions that include a work-focused problem-solving component. Currently, there is limited evidence that combinations of interventions that include problem-solving skills are effective in RTW and length of sickness absence. The evidence could be strengthened if future studies conducted more detailed examinations of the intervention process and changes in coping and problem-solving skills. It will also be useful to examine the long-term effects of problem-solving skills on sickness absence recurrence and work productivity.

Footnotes

Contributors: CSD led the conception, design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; she also led the writing of the overall manuscript. DL collaborated on the design, data acquisition and analysis; he contributed to the writing of the overall manuscript and led the writing of the Methods section. SB collaborated on the design and data acquisition and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. MCWJ collaborated on the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors are guarantors of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by Dr Dewa's Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Public Health Agency of Canada Applied Public Health Chair (FRN#:86895). Any views expressed or errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the published papers used in this manuscript are publicly available.

References

- 1.Lim KL, Jacobs P, Ohinmaa A et al. A new population-based measure of the economic burden of mental illness in Canada. Chronic Dis Can 2008;28:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg PE, Kessler R, Birnbaum HG et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1465–75. 10.4088/JCP.v64n1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens T, Jourbert N. The economic burden of mental health problems in Canada. Chronic Dis Can 2001;22:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewa CS, McDaid D, Ettner SL. An international perspective on worker mental health problems: who bears the burden and how are costs addressed? Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewa CS, Chau N, Dermer S. Examining the comparative incidence and costs of physical and mental health-related disabilities in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:758–62. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181e8cfb5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson KM, Rothstein HR. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol 2008;13:69–93. 10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Klink JJ, Blonk RW, Schene AH et al. The benefits of interventions for work-related stress. Am J Public Health 2001;91:270–6. 10.2105/AJPH.91.2.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewa CS, Lin E, Kooehoorn M et al. Association of chronic work stress, psychiatric disorders, and chronic physical conditions with disability among workers. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:652–8. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivancevich JM, Matteson MT, Freedman SM et al. Worksite stress management interventions. Am Psychol 1990;45:252–61. 10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarus R. Coping theory and research: past, present, future. Psychosom Med 1993;55:234–47. 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rhenen W, Schaufeli WB, van Dijk FJ et al. Coping and sickness absence. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2008;81:461–72. 10.1007/s00420-007-0238-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem solving therapies for depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2007;22:9–15. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobasa SC, Maddi SR, Kahn S. Hardiness and health: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol 1982;42:168–77. 10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S. Work outcomes of sickness absence related to mental disorders: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005533 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Transforming disability into ability: policies to promote work and income security for disabled people. OECD Publishing, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Group CSM, Group CBM. Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 2008:187–241. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebergen DS, Bruinvels DJ, Bezemer PD et al. Guideline-based care of common mental disorders by occupational physicians (CO-OP study): a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:305–12. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181990d32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebergen DS, Bruinvels DJ, van der Beek AJ et al. Design of a randomized controlled trial on the effects of counseling of mental health problems by occupational physicians on return to work: the CO-OP-study. BMC Public Health 2007;7:183 10.1186/1471-2458-7-183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebergen DS, Bruinvels DJ, van Tulder MW et al. Cost-effectiveness of guideline-based care for workers with mental health problems. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:313–22. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181990d8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Klink JJ, Blonk RW, Schene AH et al. Reducing long term sickness absence by an activating intervention in adjustment disorders: a cluster randomised controlled design. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:429–37. 10.1136/oem.60.6.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brouwers EP, Tiemens BG, Terluin B et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce sickness absence in patients with emotional distress or minor mental disorders: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:223–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brouwers EP, de Bruijne MC, Terluin B et al. Cost-effectiveness of an activating intervention by social workers for patients with minor mental disorders on sick leave: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:214–20. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Ader HJ et al. Collaborative care for sick-listed workers with major depressive disorder: a randomised controlled trial from the Netherlands Depression Initiative aimed at return to work and depressive symptoms. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:223–30. 10.1136/oemed-2012-100793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlasveld MC, Anema JR, Beekman AT et al. Multidisciplinary collaborative care for depressive disorder in the occupational health setting: design of a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:99 10.1186/1472-6963-8-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hees HL, Koeter MW, de Vries G et al. Effectiveness of adjuvant occupational therapy in employees with depression: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2010;10:558 10.1186/1471-2458-10-558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hees HL, de Vries G, Koeter MW et al. Adjuvant occupational therapy improves long-term depression recovery and return-to-work in good health in sick-listed employees with major depression: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:252–60. 10.1136/oemed-2012-100789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nystuen P, Hagen KB. Feasibility and effectiveness of offering a solution-focused follow-up to employees with psychological problems or muscle skeletal pain: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2003;3:19 10.1186/1471-2458-3-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arends I, van der Klink JJ, van Rhenen W et al. Prevention of recurrent sickness absence in workers with common mental disorders: results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 2014;71:21–9. 10.1136/oemed-2013-101412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]