Abstract

Objectives

Cadmium is a non-essential toxic metal with multiple adverse health effects. Cadmium has been shown to be associated with cardiovascular diseases, but few studies have investigated heart failure (HF) and none of them reported atrial fibrillation (AF). We examined whether cadmium exposure is associated with incidence of HF or AF.

Design

A prospective, observational cohort study with a 17-year follow-up.

Setting

The city of Malmö, Sweden.

Participants

Blood cadmium levels were measured in 4378 participants without a history of HF or AF (aged 46–67 years, 60% women), who participated in the Malmö Diet and Cancer (MDC) study during 1992–1994.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Incidence of HF and AF were identified from the Swedish hospital discharge register.

Results

143 participants (53% men) were diagnosed with new-onset HF and 385 individuals (52% men) were diagnosed with new-onset AF during follow-up for 17 years. Blood cadmium in the sex-specific 4th quartile of the distribution was significantly associated with incidence of HF. The (HR, 4th vs 1st quartile) was 2.64 (95% CI 1.60 to 4.36), adjusted for age, and 1.95 (1.02 to 3.71) after adjustment also for conventional risk factors and biomarkers. The blood cadmium level was not significantly associated with risk of incident AF.

Conclusions

Blood cadmium levels in the 4th quartile were associated with increased incidence of HF in this cohort with comparatively low exposure to cadmium. Incidence of AF was not associated with cadmium.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH, TOXICOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large cohort with extensive information of cadmium and cardiovascular risk factors was studied.

Incidence of heart failure (HF) and atrial fibrillation was monitored during a long follow-up.

We were unable to detect cases of HF that were diagnosed in the outpatient setting or undiagnosed. Therefore, it is unclear whether the present results could be generalised to less severe forms of HF.

Introduction

Cadmium is a non-essential toxic metal, which can be absorbed through smoking, diet and occupational exposure in certain industries. The elimination of cadmium from the human body is a slow process—the biological half-life has been estimated to be 10–40 years.1 2 Previous studies have shown that exposure to cadmium is low in the Swedish population as compared to, for example, studies from the USA3 4 and the Far East.5 Smoking and diets including vegetables, whole grain and potatoes are important sources of cadmium in Sweden.6 Occupational exposures have historically caused very exposures; however, this is now an unusual reason for cadmium exposure in Sweden.7

Multiple adverse health effects of cadmium exposure have been reported, such as increased risk of renal dysfunction,1 6 8 9 osteoporosis9–11 and cancer.12–14 Recent studies also found that cadmium was associated with the prevalence and future growth of atherosclerotic plaques15 and with cardiovascular disease (CVD).16 17 However, to the best of our knowledge, only two studies, both in the USA, have investigated the association between cadmium and heart failure (HF)3 16 Peters et al3 conducted a cross-sectional study in a sample from the US general population, and found both blood and urinary cadmium to be associated with self-reported prevalence of HF, and the association was similar among men and women. Tellez-Plaza et al16 reported an association between urinary cadmium and HF in a prospective cohort study of 3348 American Indian adults aged 45–74 years. There is experimental support for a direct toxic effect of cadmium on the heart muscle cells and possibly also the cardiac conduction system.18–23 In humans, autopsy studies have shown that the myocardial content of cadmium increases with age, up to late middle age, and mirrors the exposure to cadmium.24

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has explored the relationship between cadmium and the incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF). AF is a comorbid condition among patients with HF who share risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease and valvular disease.25–27

Thus, the purpose of this population-based study was to explore whether elevated blood cadmium levels are associated with the incidence of HF or AF in middle-aged participants.

Methods

Study population

The Malmö Diet and Cancer (MDC) is a prospective cohort study from the city of Malmö, Sweden with baseline examination between March 1991 and September 1996.28 29 Participants filled out a self-administered questionnaire and underwent physical examination and sampling of peripheral venous blood. The participant rate was 41%. A random sample of the MDC cohort, the MDC cardiovascular cohort (MDC-CC) (N=6103), was invited to take part in a study of the epidemiology of carotid artery disease between 1991 and 1994.30 Blood samples were donated by 5540 of them after an overnight fast, and cadmium could be measured in 4952 participants (aged 46–68 years, 60% women). Individuals with a history of HF (n=8) or AF (n=42) at baseline were excluded from the analysis of the respective outcomes. The final study population included 4378 participants after exclusion of participants with missing values on conventional cardiovascular risk factors and biomarkers.

Measurements and definitions

The self-administered questionnaire provided information on current use of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and antidiabetic medication, smoking habits, marital status and educational status.28 Waist circumference (in cm) was measured midway between the lowest rib margin and iliac crest. Blood pressure was measured once using a mercury-column sphygmomanometer after 10 min of rest in the supine position. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a self-reported physician's diagnosis of diabetes, use of antidiabetic medications or fasting whole blood glucose level greater than 109 mg/dL (eg, ≥6.1 mmol/L). 31 History of a coronary event at the baseline examination was retrieved from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register. Participants were categorised into current smokers (those who smoked regularly or occasionally), former smokers or never-smokers. Pack-years of smoking were calculated by the years of smoking X the number of daily cigarettes, divided by 20. As never smokers were marked as zero, pack-years were available in 3597 participants and 781 participants missing information on pack-years. High alcohol consumption was defined as >40 g alcohol per day for men and >30 g per day for women. Marital status was categorised as being married or not. Educational level was divided into less than 9, 9–11 and 12 years or more of education.

Laboratory measurements

The blood cadmium concentrations were calculated using erythrocyte concentrations of cadmium adjusted for haematocrit. Cadmium was analysed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Agilent 7700x ICP-MS, Agilent Technologies). All samples were analysed in three different rounds with external quality control samples being included. Two QC samples were used (Seronorm Trace Elements Whole Blood L-1, Lot No. 1 103 128 and Seronorm Trace Elements Whole Blood L-2, Lot No.1103129, Sero AS, Billingstad Norway). The results from all rounds versus recommended limits were 0.34±0.02 µg/L (N=70) versus 0.32–0.40 µg/L and 5.7±0.18 µg/L (N=70) versus 5.4–6.2 µg/L. The results were similar for the three different rounds. Furthermore, 20 erythrocyte samples (range 0.2–0.96 µg/L) were used to compare with those from another laboratory (Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Lund, Sweden). The results showed good agreement with a Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.99 and a slope of 1.04 (SE 0.04).

Measurements of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) were performed on fresh blood samples according to standard procedures at the Department of Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital Malmö. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) concentration was calculated according to Friedewald's formula. Plasma biomarkers were measured from fasting plasma samples that had been frozen at −80°C immediately after collection. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was analysed using the Tina-quant CRP latex assay (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Plasma creatinine (μmol/L) was analysed with the Jaffé method, standardised according to the International Standardization with isotope dilution mass spectometry (IDMS).

Follow-up and ascertainment of cardiovascular events

All cases were retrieved from the Swedish hospital discharge register. This register has been operating in the south of Sweden since 1970 and became nationwide in 1987. HF was defined according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code 427.00, 427.10 and 428.99 (ICD-8); 428 (ICD-9); and I50, I11 (ICD-10) as the primary diagnosis.32 AF was defined using diagnosis codes 427.92 (ICD-8), 427D (ICD-9) and I48 (ICD-10).33 Validation studies have shown that the Swedish hospital discharge register has a case validity of 95% for a primary diagnosis of HF32 and a case validity of 98% for AF.33

Statistical analysis

Individuals with a history of HF or AF at baseline were excluded from the respective analyses. All participants were followed from the baseline examination until death, emigration from Sweden or 31 December 2010, whichever came first. In addition, follow-up time was stopped at a first event of HF for the study of incidence of HF, and at a first event of AF for the study of incidence of AF. A total of 30 (0.7%) participants emigrated from Sweden during the follow-up.

hsCRP showed a right-skewed distribution and was log-transformed. Cross-sectional relations of sex-specific cadmium quartiles (ie, with the same proportions of men and women in each quartile) to cardiovascular risk factors were assessed using one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and logistic regression for dichotomous variables. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine the association between cadmium (in sex-specific quartiles) and incidence of HF or AF. HRs with 95% CIs were calculated. The basic model was adjusted for age. In model 2, we also adjusted for other established cardiovascular risk factors, that is, systolic blood pressure, use of blood pressure-lowering or lipids-lowering medications, presence of diabetes mellitus, history of a coronary event, waist circumference, smoking status, alcohol intake, LDL, HDL, hsCRP, plasma creatinine, and marital and educational status. The fit of the proportional hazards model was checked visually by plotting the incidence rates over time and by entering time-dependent variables into the model. Possible interactions between cadmium and cardiovascular risk factors on incident HF or AF were explored by introducing interaction terms in the multivariate model. The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to illustrate the incidence of HF in relation to cadmium. The association between incident HF and cadmium level was also assessed using a restricted cubic spline with five knots of blood cadmium in models adjusted for age, sex and smoking status. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS V.20 (IBM Corp.) or Stata software V.12.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Cardiovascular risk factors at the baseline examination in relation to the sex-specific quartiles of cadmium are presented in table 1. Age, hsCRP, HDL, plasma creatinine, systolic blood pressure, history of diabetes, history of a coronary event, current smoking, high alcohol intake, being unmarried and low educational level were significantly associated with the cadmium level, table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the MDC study cohort in relation to the sex-specific quartiles (Q1–Q4) of blood cadmium

| Quartiles of blood cadmium |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDC (N=4378) | Overall | Q1 (n=1094) | Q2 (n=1095) | Q3 (n=1095) | Q4 (n=1094) | p Value |

| Blood cadmium, men (µg/L), median (range) | 0.24 (0.02–5.07) | 0.12 (0.02–0.15) | 0.19 (0.15–0.24) | 0.31 (0.24–0.49) | 0.98 (0.49–5.07) | |

| Blood cadmium, women (µg/L), median (range) | 0.27 (0.03–4.83) | 0.14 (0.03–0.18) | 0.22 (0.18–0.27) | 0.34 (0.27–0.49) | 0.97 (0.49–4.83) | |

| Age (years) | 57.4±5.9 | 56.9±5.9 | 57.9±6.0 | 58.3±5.8 | 56.8±5.9 | <0.001 |

| Male sex (%) | 40.2 | 40.1 | 40.2 | 40.2 | 40.1 | 1.00 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 83.2±12.8 | 83.2±12.5 | 83.6±13.2 | 83.8±12.6 | 82.7±12.9 | 0.16 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 141±19 | 140±18 | 141±19 | 142±19 | 140±19 | 0.03 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 4.18±0.99 | 4.20±1.0 | 4.18±1.0 | 4.13±1.0 | 4.23±1.0 | 0.13 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.39±0.37 | 1.39±0.37 | 1.42±0.38 | 1.41±0.37 | 1.36±0.37 | 0.001 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 2.53±4.3 | 2.28±4.3 | 2.18±3.8 | 2.41±3.8 | 3.24±5.3 | <0.001 |

| Plasma creatinine (μmol/L) | 84.7±16 | 85.5±13 | 85.5±17 | 86.2±17 | 82.5±16 | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure-lowering medication (%) | 15.7 | 13.5 | 17.3 | 18.1 | 14.1 | 0.62 |

| Lipid-lowering medication (%) | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 0.28 |

| Diabetes (%) | 3.6 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 0.01 |

| History of a coronary event (%) | 1.4 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.001 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||||

| Current smoker (%) | 26.1 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 15.1 | 80.7 | |

| Former smoker (%) | 33.5 | 31.9 | 41.9 | 46.8 | 13.3 | |

| Never smoker (%) | 40.5 | 64.4 | 53.3 | 38.1 | 6.0 | |

| Pack-years | 10.7±18.6 | 2.4±10.2 | 4.7±12.6 | 8.6±18.6 | 25.0±20.7 | |

| High alcohol intake (%) | 3.5 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 0.008 |

| Married (%) | 68.4 | 71.5 | 74.7 | 68.4 | 59.0 | <0.001 |

| Low education (%) | 45.6 | 39.7 | 43.8 | 46.6 | 52.4 | <0.001 |

All values are mean±SD, unless otherwise stated.

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MDC, Malmö Diet and Cancer; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Incidence of HF and AF in relation to cadmium

During a mean follow-up of 16.8 years, 143 participants (53% men) had a first hospital diagnosis of HF. A total of 385 individuals (52% men) were diagnosed with AF during the follow-up.

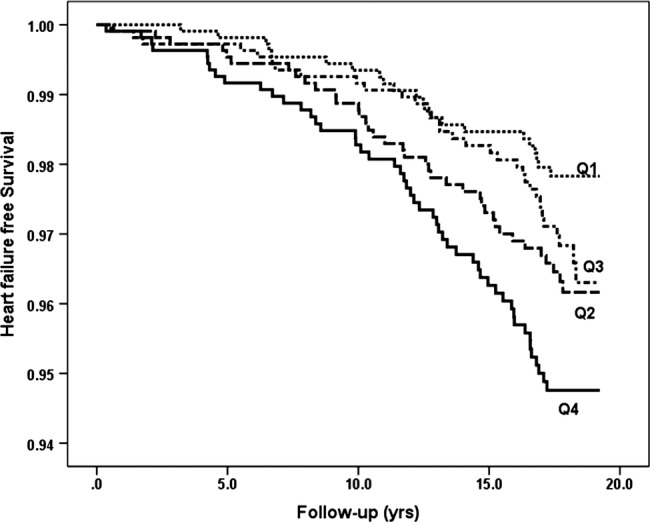

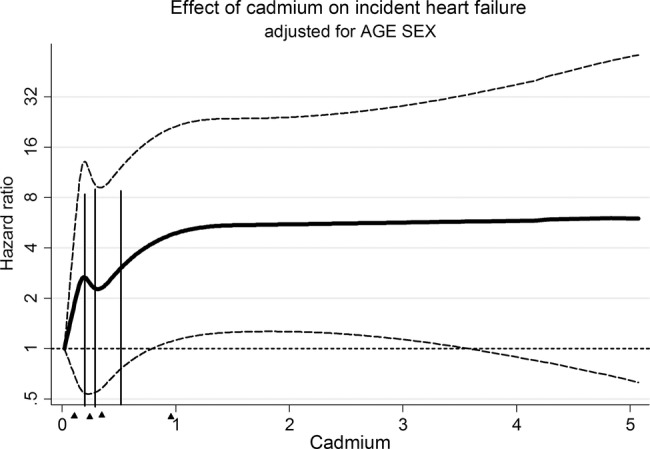

Participants in the 4th compared to the 1st quartile of cadmium had a significantly higher risk for incident HF (HR 2.64, 95% CI 1.60 to 4.36) after adjustment for age, table 2 and figure 1. This association remained significant after further adjustment for possible confounders, HR 1.95 (1.02 to 3.72). However, the relationship across quartiles of cadmium was non-linear (p for trend 0.21). The restricted cubic spline model of incident HF across cadmium levels, adjusted for age, sex and smoking status, is shown in figure 2. The risk for HF was not linear across the cadmium level, and the 4th quartile of blood cadmium (>0.49 µg/L) indicated an increased risk for HF.

Table 2.

Incidence of HF or AF in relation to the sex-specific quartiles of blood cadmium

| Sex-specific quartiles of blood cadmium |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P trend | |

| HF, n, per 1000 p-y | 22 (1.2) | 38 (2.0) | 33 (1.8) | 50 (2.8) | |

| HR (95% CI), model 1 | 1.00 | 1.56 (0.92 to 2.63) | 1.28 (0.75 to 2.20) | 2.64 (1.60 to 4.36) | <0.001 |

| HR (95% CI), model 2 | 1.00 | 1.59 (0.92 to 2.72) | 1.04 (0.59 to 1.84) | 1.95 (1.02 to 3.72) | 0.21 |

| AF, n, per 1000 p-y | 83 (4.5) | 90 (4.9) | 122 (6.7) | 90 (5.2) | |

| HR (95% CI), model 1 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.74 to 1.34) | 1.32 (1.00 to 1.75) | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.68) | 0.08 |

| HR (95% CI), model 2 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.73 to 1.33) | 1.19 (0.89 to 1.59) | 1.02 (0.69 to 1.51) | 0.45 |

HR model 1 adjusted for age.

HR model 2 adjusted for age, systolic blood pressure, use of blood pressure-lowering or lipids-lowering medications, presence of diabetes mellitus, history of a coronary event, waist circumference, smoking status, alcohol intake, LDL, HDL, hsCRP, plasma creatinine, marital and educational status.

AF, atrial fibrillation; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HF, heart failure; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; p-y, person-year.

Figure 1.

Incidence of heart failure in relation to sex-specific quartiles (Q1–Q4) of blood cadmium.

Figure 2.

Cubic splines model for incident heart failure as a function of cadmium levels in blood. Hazards ratio is adjusted for age and sex and smoking status. Triangles indicate median cadmium concentrations for Q1–Q4.

A sensitivity analysis with additional adjustment for pack-years was performed. The result was similar (HR for 4th vs 1st quartile: 1.98: 1.04 to 3.78, p=0.038). We also performed a sensitivity analysis using erythrocyte cadmium instead of blood cadmium, and the results were essentially the same, online supplementary table S1. In addition, we analysed the association between blood cadmium and HF using quartile limits based on the entire sample instead of sex-specific cut-offs. The HR (Q4 vs Q1) was 1.83 (1.00 to 3.36, p=0.052) for the adjusted model when sex was added to the covariates. The relationship between cadmium and HF was only observed in participants above 57 years of age. HR for Q4 versus Q1 for sex-specific quartiles cadmium was 1.11 (0.26 to 4.73, p=0.888) among the 46–57-year-olds and 2.20 (1.07 to 4.50, p=0.031) among those above 57–67 years. However, only 24 HF cases occurred in participants aged 46–57 years.

Sensitivity analysis was performed separately for men and women to examine the effects of cadmium on the incidence of HF. The significant association between cadmium and incident HF was only found among men, table 3. Additional adjustment for menopausal status in women did not change the association, data not shown. Since cadmium exposure is higher in smokers, we also performed a separate analysis of incidence of HF in never smoking participants. The point-estimate was similar to that in all participants, although it was not statistically significant (table 4).

Table 3.

Incidence of HF in relation to the sex-specific quartiles of blood cadmium among men and women

| Quartiles of blood cadmium |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P trend | |

| Men | |||||

| HF, n, per 1000 p-y | 6 (0.8) | 23 (3.2) | 18 (2.5) | 29 (4.2) | |

| HR (95% CI), model 1 | 1.00 | 3.61 (1.47 to 8.86) | 2.58 (1.02 to 6.50) | 5.39 (2.24 to 13.00) | <0.001 |

| HR (95% CI), model 2 | 1.00 | 3.37 (1.29 to 8.78) | 1.76 (0.66 to 4.73) | 3.91 (1.32 to 11.54) | 0.18 |

| Women | |||||

| HF, n, per 1000 p-y | 16 (1.4) | 15 (1.3) | 15 (1.3) | 21 (1.9) | |

| HR (95% CI), model 1 | 1.00 | 0.82 (0.40 to 1.65) | 0.80 (0.39 to 1.61) | 1.58 (0.82 to 3.02) | 0.20 |

| HR (95% CI), model 2 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.44 to 1.83) | 0.74 (0.35 to 1.54) | 1.18 (0.49 to 2.82) | 0.99 |

HR model 1 adjusted for age.

HR model 2 adjusted for age, systolic blood pressure, use of blood pressure-lowering or lipids-lowering medications, presence of diabetes mellitus, history of a coronary event, waist circumference, smoking status, alcohol intake, LDL, HDL, hsCRP, plasma creatinine, marital and educational status.

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HF, heart failure; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; p-y, person-year.

Table 4.

Additional analysis on incidence of HF in relation to sex-specific quartiles of blood cadmium among never smokers

| Quartiles of blood cadmium |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P trend | |

| HF, n, per 1000 p-y | 8 (1.7) | 23 (2.7) | 9 (3.4) | 2 (6.0) | |

| HR (95% CI), model 1 | 1.00 | 3.05 (1.36 to 6.83) | 1.48 (0.57 to 3.82) | 2.23 (0.47 to 10.50) | 0.37 |

| HR (95% CI), model 2 | 1.00 | 3.72 (1.63 to 8.51) | 1.51 (0.56 to 4.03) | 2.87 (0.60 to 13.85) | 0.11 |

HR model 1 adjusted for age.

HR model 2 adjusted for age, systolic blood pressure, use of blood pressure-lowering or lipids-lowering medications, presence of diabetes mellitus, history of a coronary event, waist circumference, alcohol intake, LDL, HDL, hsCRP, plasma creatinine, marital and educational status.

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HF, heart failure; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; p-y, person-year.

An elevated blood cadmium level was not significantly associated with increased incidence of AF, when adjusted for age (HR 1.25, 0.93 to 1.68), table 2. The associations were further attenuated when adjusting for other risk factors.

In the multivariate adjusted model for incident HF, age, use of blood pressure-lowering medication, diabetes, waist circumference, hsCRP and history of a coronary event were independently associated with an increased risk for HF. Age, waist circumference, use of lipid-lowering medication, antihypertensive medication and low LDL were significantly associated with AF in the multivariate analysis. No significant interaction was observed between cadmium level and other cardiovascular risk factors on incident HF or AF, respectively.

Discussion

This large, prospective Swedish population-based study showed a significantly higher incidence of HF in participants in the 4th quartile of blood cadmium compared to those in the 1st quartile. However, the relationship was non-linear and no increased risk was found for participants in the 3rd quartile of cadmium. Our results extend data from two previous studies from the USA which were based on self-reported HF in a cross-sectional study3 and the incidence of HF in an ethnic minority with much higher levels of exposure to cadmium than the median levels in this study (0.24 µg/L in men and 0.27 µg/L in women).16 The results support the hypothesis of a relationship between increased cadmium levels and risk of HF. However, we found no significant association between blood cadmium and incidence of AF in the present study.

The mechanisms underlying the association between cadmium and HF are unclear. Cadmium has been associated with many cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension,5 34 smoking and kidney disease,6 8 which might partly explain the association between cadmium and HF. Cadmium was significantly associated with baseline blood pressure, current smoking, history of a coronary event and plasma creatinine in our study. However, cadmium was associated with increased risk of HF after adjustment for the baseline levels of these risk factors.

Cadmium could potentially replace and interact with the homeostasis of several essential metals, such as zinc, iron and calcium.35 It has been reported that cadmium could have cardiotoxic effects, which might explain the association between cadmium and HF. Chronic exposure to cadmium causes degenerative changes to myocardial cells in rats, and cardiac depressant effects following low dose cadmium exposure have been reported in mice.18 19 Cadmium may affect the tissue structure and integrity of the heart muscle by oxidative stress and increased reactive oxygen species production or by DNA methylation.20 21 Cadmium also affects the cardiac conduction system by interfering with calcium-mediated physiological and biochemical processes.22 Blockade of L-type calcium channels and altered outward potassium current in ventricular myocytes were also observed in vivo.23 36

HF is a heterogeneous syndrome characterised by impairment of the heart to fill and/or eject blood commensurate with the metabolic needs of the body, resulting in pulmonary or venous congestion.37 Traditionally, HF has been associated with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HF with reduced ejection fraction—HFREF). During the past decades, it has been widely recognised that HF also occurs with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF),38 characterised by normal left ventricular systolic function and abnormal diastolic function in combination with clinical signs or symptoms of HF.39 The prevalence of HF increases strongly after middle age and is about 10% among those above the age of 75 years.38 Recent studies have shown that half of the cases with HF have HFPEF.38 In comparison with HFREF, patients with HFPEF are older, more often women, more often hypertensive and have a higher prevalence of AF but a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease.38 Non-cardiovascular comorbidities seem to be more prevalent and include renal impairment, chronic lung diseases, anaemia and other diseases.38 A meta-analysis has shown that HFPEF is associated with a 50% lower HR for mortality compared with HFREF and a higher likelihood of non-cardiovascular death.40 A limitation of this study is that we were unable to distinguish between different types of HF. Since the mean age of the cohort was rather young (57 years) and the relationship between cadmium and HF was only found in men, it could be speculated that the cadmium level is mainly associated with HFREF.

Smoking is a major source of cadmium exposure and an established cardiovascular risk factor. In our study, the association between cadmium and incident HF remained after adjustment for smoking status. We did not have information on serum cotinine, but adjustment for pack-years, which were available in a major part of the cohort, did not change the results. In addition, the point-estimate of the association between cadmium and incidence of HF was similar in a separate analysis of never smokers, although not attaining statistical significance. The major source of cadmium in non-smokers is the high dietary intake of contaminated healthy food items, such as whole grains and vegetables.1 41 The high intake of whole grains and vegetables could have protective effects and reduce the risk of CVD.42 43 Hence, a more healthy diet could counterbalance the adverse effects of cadmium in non-smokers, and this could hypothetically explain the non-linear association between cadmium and HF.

The strength of this study included a large number of participants and events during a long follow-up period. The cardiovascular end points were retrieved from national hospital registers in Sweden with high validity for HF32 and AF.33 Since all HF events in the study had HF as the primary diagnosis and were hospitalised, we can assume that the diagnosis was valid and that HF was quite severe in most cases. A limitation is that we were unable to detect cases of HF that were diagnosed in the outpatient setting or undiagnosed. Therefore, it is unclear whether the present results could be generalised to less severe forms of HF.

In conclusion, an elevated level of cadmium in the blood was associated with increased incidence of HF. Incidence of AF was not associated with cadmium. The results from this population-based study give support to the hypothesis of a relationship between cadmium and increased risk of HF.

Footnotes

Contributors: YB, LB, MP, BH, BF and GE were involved in the design, data collection, analysis and write-up of the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2011-3891), the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20130249; 20120364); Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2012-0025 and 2014-0171), and the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Region Västra Götaland and Sahlgrenska University Hospital and ALF between Region Skåne and Lund University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the regional Ethics Committee (LU51/90) and all participants provided written informed consent. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nordberg GF, Nogawa K, Nordberg M et al. Cadmium. In: Nordberg GF, Fowler B, Nordberg M et al., eds Handbook on the toxicology of Metals. 2007:445–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerstrom M, Barregard L, Lundh T et al. The relationship between cadmium in kidney and cadmium in urine and blood in an environmentally exposed population. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2013;268:286–93. 10.1016/j.taap.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters JL, Perlstein TS, Perry MJ et al. Cadmium exposure in association with history of stroke and heart failure. Environ Res 2010;110:199–206. 10.1016/j.envres.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellez-Plaza M, Navas-Acien A, Menke A et al. Cadmium exposure and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the US general population. Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:1017–22. 10.1289/ehp.1104352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MS, Park SK, Hu H et al. Cadmium exposure and cardiovascular disease in the 2005 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ Res 2011;111:171–6. 10.1016/j.envres.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarup L, Akesson A. Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009;238:201–8. 10.1016/j.taap.2009.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemikalieinspektionen©. Cadmium levels must decrease—For the sake of public health: The assessment of cadmium in mineral fertilizers in focus (Report 1/11) (in swedish). 2011. http://www.kemikalieinspektionen.se

- 8.Navas-Acien A, Tellez-Plaza M, Guallar E et al. Blood cadmium and lead and chronic kidney disease in US adults: a joint analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:1156–64. 10.1093/aje/kwp248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akesson A, Barregard L, Bergdahl IA et al. Non-renal effects and the risk assessment of environmental cadmium exposure. Environ Health Perspect 2014;122:431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staessen JA, Roels HA, Emelianov D et al. Environmental exposure to cadmium, forearm bone density, and risk of fractures: prospective population study. Public Health and Environmental Exposure to Cadmium (PheeCad) Study Group. Lancet 1999;353:1140–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09356-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engstrom A, Michaelsson K, Suwazono Y et al. Long-term cadmium exposure and the association with bone mineral density and fractures in a population-based study among women. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:486–95. 10.1002/jbmr.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IARC International Agency for Research on Cancer Cacc. Cadmium and cadmium compounds 2012. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100C/mono100C-8.pdf 100.

- 13.Julin B, Wolk A, Akesson A. Dietary cadmium exposure and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in a prospective cohort of Swedish women. Br J Cancer 2011;105:441–4. 10.1038/bjc.2011.238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julin B, Wolk A, Johansson JE et al. Dietary cadmium exposure and prostate cancer incidence: a population-based prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer 2012;107:895–900. 10.1038/bjc.2012.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagerberg B, Bergstrom G, Boren J et al. Cadmium exposure is accompanied by increased prevalence and future growth of atherosclerotic plaques in 64-year-old women. J Intern Med 2012;272:601–10. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tellez-Plaza M, Guallar E, Howard BV et al. Cadmium exposure and incident cardiovascular disease. Epidemiology 2013;24:421–9. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828b0631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tellez-Plaza M, Jones MR, Dominguez-Lucas A et al. Cadmium exposure and clinical cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2013;15:356 10.1007/s11883-013-0356-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozturk IM, Buyukakilli B, Balli E et al. Determination of acute and chronic effects of cadmium on the cardiovascular system of rats. Toxicol Mech Methods 2009;19:308–17. 10.1080/15376510802662751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turdi S, Sun W, Tan Y et al. Inhibition of DNA methylation attenuates low-dose cadmium-induced cardiac contractile and intracellular Ca(2+) anomalies. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2013;40:706–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamall IS, Naik M, Sprowls JJ et al. A comparison of the effects of dietary cadmium on heart and kidney antioxidant enzymes: evidence for the greater vulnerability of the heart to cadmium toxicity. J Appl Toxicol 1989;9:339–45. 10.1002/jat.2550090510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Fang J, Leonard SS et al. Cadmium inhibits the electron transfer chain and induces reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;36:1434–43. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prentice RC, Hawley PL, Glonek T et al. Calcium-dependent effects of cadmium on energy metabolism and function of perfused rat heart. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1984;75:198–210. 10.1016/0041-008X(84)90202-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen JB, Jiang B, Pappano AJ. Comparison of L-type calcium channel blockade by nifedipine and/or cadmium in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J pharmacol exp ther 2000;294:562–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vuori E, Huunan-Seppala A, Kilpio JO et al. Biologically active metals in human tissues. II. The effect of age on the concentration of cadmium in aorta, heart, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas and skeletal muscle. Scand J Work Environ Health 1979;5:16–22. 10.5271/sjweh.2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonarow GC, Corday E. Overview of acutely decompensated congestive heart failure (ADHF): a report from the ADHERE registry. Heart Fail Rev 2004;9:179–85. 10.1007/s10741-005-6127-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:2920–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anter E, Jessup M, Callans DJ. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: treatment considerations for a dual epidemic. Circulation 2009;119:2516–25. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berglund G, Elmstahl S, Janzon L et al. The Malmo Diet and Cancer Study. Design and feasibility. J Intern Med 1993;233:45–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melander O, Newton-Cheh C, Almgren P et al. Novel and conventional biomarkers for prediction of incident cardiovascular events in the community. JAMA 2009;302:49–57. 10.1001/jama.2009.943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Janzon L et al. Relation between insulin resistance and carotid intima-media thickness and stenosis in non-diabetic subjects. Results from a cross-sectional study in Malmo, Sweden. Diabet Med 2000;17:299–307. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15:539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingelsson E, Arnlöv J, Sundström J et al. The validity of a diagnosis of heart failure in a hospital discharge register. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:787–91. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JG, Platonov PG, Hedblad B et al. Atrial fibrillation in the Malmo Diet and Cancer study: a study of occurrence, risk factors and diagnostic validity. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:95–102. 10.1007/s10654-009-9404-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tellez-Plaza M, Navas-Acien A, Crainiceanu CM et al. Cadmium exposure and hypertension in the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Environ Health Perspect 2008;116:51–6. 10.1289/ehp.10764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moulis JM. Cellular mechanisms of cadmium toxicity related to the homeostasis of essential metals. Biometals 2010;23:877–96. 10.1007/s10534-010-9336-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Follmer CH, Lodge NJ, Cullinan CA et al. Modulation of the delayed rectifier, IK, by cadmium in cat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol 1992;262:C75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2007–18. 10.1056/NEJMra021498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam CS, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E et al. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:18–28. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulus WJ, Tschope C, Sanderson JE et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2539–50. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somaratne JB, Berry C, McMurray JJ et al. The prognostic significance of heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a literature-based meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:855–62. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Julin B, Bergkvist C, Wolk A et al. Cadmium in diet and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Epidemiology 2013;24:880–5. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182a777c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van't Veer P, Jansen MC, Klerk M et al. Fruits and vegetables in the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Public Health Nutr 2000;3:103–7. 10.1017/S1368980000000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flight I, Clifton P. Cereal grains and legumes in the prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke: a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;60:1145–59. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]