Abstract

Objectives

Gender differences in prevalence and prognostic impact of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have been poorly evaluated. In STEMI, female gender has been independently associated with an increased risk of mortality. CKD has been found to be an important prognostic marker in myocardial infarction. The aim of this study was to evaluate gender differences in prevalence and prognostic impact of CKD on short-term and long-term mortality.

Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Setting

The national quality register SWEDEHEART was used. In the beginning of the study period, 94% of the Swedish coronary care units contributed data to the register, which subsequently increased to 100%. The glomerular filtration rate was estimated (eGFR) according to Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD) and Cockcroft-Gault (CG).

Participants

All patients with STEMI registered in SWEDEHEART from the years 2003–2009 were included (37 991 patients, 66% men).

Main results

Women had 1.6 (MDRD) to 2.2 (CG) times higher multivariable adjusted risk of CKD. Half of the women had CKD according to CG. CKD was associated with 2–2.5 times higher risk of in-hospital mortality and approximately 1.5 times higher risk of long-term mortality in both genders. Each 10 mL/min decline of eGFR was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality (22–33% and 9–16%, respectively) and this did not vary significantly by gender. Both in-hospital and long-term mortality were doubled in women. After multivariable adjustment including eGFR, there was no longer any gender difference in early outcome and the long-term outcome was better in women.

Conclusions

Among patients with STEMI, female gender was independently associated with CKD. Reduced eGFR was a strong independent risk factor for short-term and long-term mortality without a significant gender difference in prognostic impact and seems to be an important reason why women have higher mortality than men with STEMI.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The current study included a large number of patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), with a sufficient number in each chronic kidney disease stage to assure adequate statistical analyses.

SWEDEHEART registry is a unique Swedish National Quality registry, with quality control and audit measures, covering all hospitals in Sweden treating patients with STEMI. SWEDEHEART employs standardised criteria for defining myocardial infarction as well as hospital outcomes.

Long-term outcome is complete in Sweden as the vital status of all citizens is registered in the Cause of Death Registry.

One of the limitations of SWEDEHEART is its non-randomised, observational nature. Thus multivariate analyses were used in order to reduce the bias inherent in this type of study.

The calculations of estimated glomerular filtration rate were based on serum creatinine (s-creatinine) on admission. Thus we cannot exclude inclusion of a few patients with acute renal failure, where the admission s-creatinine may not represent a true estimation of the baseline kidney function.

Introduction

During the past decade, chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been found to be one of the most important prognostic markers after myocardial infarction (MI). Even mildly reduced kidney function affects the prognosis in acute coronary syndrome.1–6 As soon as a value of 70–90 mL/min has been reached, each 10 mL decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) increases the risk of mortality by 10–14% post-MI.1 6 In addition to prognostic information, it is important to be aware of the presence of CKD in ST segment elevation MI (STEMI), as the majority of patients will undergo primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a contrast load that may cause deterioration in an already reduced kidney function. Cardiologists have gradually improved their ability to evaluate kidney function as one part of the overall risk assessment and also to aid in making drug dose adjustments. The Cockcroft-Gault (CG)7 and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD)8 formulas are the most widely used, but they differ in several important respects. MDRD is recommended for detecting CKD and CG is recommended for making drug dose adjustments. CG has been shown to be somewhat more predictive of mortality than MDRD after MI.9

In STEMI, female gender has been independently associated with an increased risk of mortality, especially in the early phase.10–12 Gender differences in the prevalence and prognostic impact of CKD in STEMI have been poorly evaluated in the literature. According to a small single-centre study on patients with STEMI, women had CKD more often than men (67% vs 27%), according to MDRD, and CKD had a stronger prognostic impact in women.13

Thus the first objective of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of the different stages of CKD in women and men with STEMI and to examine whether female gender is an independent predictor of CKD. The second objective was to evaluate the prognostic impact of CKD on short-term and long-term mortality, and examine if there is an interaction between gender and CKD regarding prognosis. The third objective was to evaluate if female gender is independently associated with increased short-term and long-term mortality after adjusting for CKD.

Methods

Patient population

All consecutive patients with STEMI admitted to coronary care units (CCUs) between 2003 and 2009 registered in the Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) register were included in the current study (http://www.ucr.uu.se/swedeheart). The details of the register have been previously published.14 In the beginning of the study period, 94% of the Swedish CCUs contributed with data to the register, increasing to 100% towards the end of the study period.

SWEDEHEART was also merged with the National Patient Registry (PAR) and the National Death Register. Data on prior comorbidities such as previous MI, diabetes mellitus (DM), stroke, heart failure, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral artery disease (PAD) and cancer were obtained from the PAR, which collects all discharge diagnoses for patients admitted to a hospital in Sweden since 1987. For the current study, a patient was coded as having one of the mentioned diagnoses if apparent in either SWEDEHEART or PAR. Mortality data were available for all patients and were obtained both from the SWEDEHEART (in-hospital mortality) and the National Death Register (long-term mortality).

Definitions

On the basis of serum creatinine (s-creatinine) on admission, GFR was estimated with the MDRD, and Creatinine Clearance with the CG formulas, for all patients where data on sex, age and s-creatinine were available, and regarding CG, also weight.

Renal dysfunction was staged according to the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) definition; eGFR>90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (normal), 60–90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (mild), 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (moderate), 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 (severe) and <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or receiving dialysis (renal failure).15 CKD stages 4 and 5 were analysed together in the multivariate analysis of the effect of CKD class on mortality, as we had few patients in CKD stage 5, otherwise the classes are presented separately. In order to simplify, the term eGFR will be used for both formulas from here on. CKD is defined as eGFR<60 mL/min(/1.73 m2). In table 1, the MDRD formula is used to define the CKD group.

GFR estimated according to MDRD in mL/min/1.73 m2=186 * (serum creatinine/88.4 [in µmol/L])−1.154 * age [in years]) −0.203 If women multiply the equation by 0.742

CrCl according to CG in mL/min=((140- age [in years]) * weight [in kilogram])/(serum creatinine [in µmol/L]) * (88.4/72) If women multiply the equation by 0.85

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| All women (n=12 929) | CKD* (n=4589) | Non-CKD* (n=7454) | p Value† | All men (n=25 062) | CKD* (n=4415) | Non-CKD* (n=18 902) | p Value† | p Value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 73.7 (12.1) | 79.4 (9.3) | 70.2 (12.3) | <0.001 | 66.3 (12.2) | 75.5 (10.2) | 64.2 (11.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Weight in kg, mean (SD) | 68.4 (13.9) | 67.8 (13.8) | 68.8 (14.0) | 0.001 | 82.8 (13.7) | 80.1 (14.0) | 83.3 (13.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26.1 (8.6) | 25.9 (4.8) | 26.1 (10.2) | 0.44 | 26.7 (5.1) | 26.2 (8.6) | 26.7 (4.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure in mm Hg, mean (SD) | 139.5 (31.2) | 135.8 (32.8) | 142.1 (29.6) | <0.001 | 140.1 (29.0) | 133.9 (31.2) | 141.8 (28.2) | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| Heart rate in bpm, mean (SD) | 79.1 (22.2) | 80.8 (24.9) | 78.2 (20.5) | <0.001 | 75.9 (20.4) | 79.2 (24.7) | 75.1 (19.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||||||||

| Current smoker | 3167 (27.2) | 614 (15.4) | 2376 (34.3) | <0.001 | 7126 (30.6) | 700 (18.0) | 5979 (33.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 2187 (17.1) | 1133 (25.0) | 865 (11.7) | <0.001 | 4473 (18.0) | 1339 (30.7) | 2759 (14.7) | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 542 (4.2) | 196 (4.3) | 305 (4.1) | 0.58 | 1831 (7.4) | 359 (8.3) | 1347 (7.2) | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass grafting | 280 (2.2) | 134 (2.9) | 120 (1.6) | <0.001 | 1100 (4.4) | 320 (7.3) | 691 (3.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2808 (21.8) | 1286 (28.2) | 1326 (17.9) | <0.001 | 4676 (18.8) | 1132 (25.8) | 3244 (17.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 5954 (46.8) | 2534 (56.3) | 3061 (41.6) | <0.001 | 8615 (34.9) | 2112 (48.8) | 5950 (31.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Previous heart failure | 1455 (11.3) | 933 (20.3) | 398 (5.3) | <0.001 | 1558 (6.2) | 735 (16.7) | 690 (3.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Previous stroke | 1500 (11.6) | 743 (16.2) | 640 (8.6) | <0.001 | 2196 (8.8) | 764 (17.3) | 1278 (6.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 565 (4.4) | 305 (6.7) | 214 (2.9) | <0.001 | 860 (3.4) | 354 (8.0) | 434 (2.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1264 (9.8) | 473 (10.3) | 714 (9.6) | 0.19 | 1403 (5.6) | 340 (7.7) | 967 (5.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Cancer within 3 years | 402 (3.1) | 176 (3.8) | 187 (2.5) | <0.001 | 806 (3.2) | 265 (6.0) | 480 (2.5) | <0.001 | 0.57 |

| Therapy on arrival | |||||||||

| Aspirin | 4149 (32.5) | 1965 (43.3) | 1869 (25.3) | <0.001 | 6773 (27.3) | 1888 (43.4) | 4336 (23.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Other platelet inhibitor | 571 (4.5) | 234 (5.2) | 259 (3.5) | <0.001 | 1029 (4.1) | 249 (5.7) | 641 (3.4) | <0.001 | 0.14 |

| β-blocker | 4503 (35.4) | 2088 (46.3) | 2087 (28.3) | <0.001 | 6835 (27.6) | 1849 (42.6) | 4442 (23.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1957 (15.4) | 942 (20.9) | 845 (11.4) | <0.001 | 3522 (14.2) | 1001 (23.1) | 2224 (11.9) | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 996 (9.9) | 451 (12.9) | 515 (8.3) | <0.001 | 1557 (7.9) | 442 (13.2) | 1065 (6.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Statin | 2075 (16.3) | 828 (18.3) | 1089 (14.8) | <0.001 | 4455 (18.0) | 1007 (23.3) | 3118 (16.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Procedures/therapies at CCU/cath lab | |||||||||

| Coronary angiography | 8068 (62.6) | 2419 (52.9) | 5154 (69.2) | <0.001 | 18 725 (75.0) | 2610 (59.3) | 14 938 (79.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Reperfusion therapy | 8976 (69.4) | 2464 (53.7) | 5964 (80.0) | <0.001 | 21 121 (84.3) | 2868 (65.0) | 16 852 (89.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Biochemical markers, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.1 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.2) | 0.02 | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 3.1 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.2) | <0.001 | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 8.2 (3.5) | 9.8 (4.9) | 8.2 (3.4) | <0.001 | 8.2 (3.5) | 9.2 (4.7) | 7.9 (3.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 130.5 (15.5) | 126.7 (16.5) | 132.5 (14.5) | <0.001 | 142.8 (15.8) | 135.0 (18.7) | 144.3 (14.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Troponin T (ng/L) | 5.2 (31.0) | 6.0 (35.6) | 4.3 (28.5) | <0.001 | 6.0 (29.5) | 8.4 (51.4) | 5.1 (20.6) | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 88.8 (51.6) | 125.3 (68.0) | 66.4 (11.3) | <0.001 | 98.8 (54.3) | 162.7 (98) | 83.8 (14.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| eGFR according to MDRD (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 69.4 (28.3) | 43.7 (12.3) | 85.2 (23.3) | <0.001 | 80.7 (29.6) | 45.0 (12.7) | 89.0 (26.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| eGFR according to CG (mL/min) | 65.5 (32.7) | 39.5 (15.4) | 80.0 (30.7) | <0.001 | 88.2 (37.1) | 45.5 (16.8) | 97.0 (33.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Complications | |||||||||

| Killip class I (no signs of heart failure) | 9488 (79.7) | 2980 (70.0) | 5980 (86.9) | <0.001 | 20 136 (87.2) | 3054 (74.6) | 15 879 (90.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Killip class II (rales) | 1586 (13.3) | 820 (19.3) | 643 (9.3) | 1936 (8.4) | 650 (15.9) | 1124 (6.4) | |||

| Killip class III (pulmonary oedema) | 230 (1.9) | 136 (3.2) | 76 (1.1) | 207 (0.9) | 103 (2.5) | 91 (0.5) | |||

| Killip class IV (cardiogenic shock) | 606 (5.1) | 320 (7.5) | 185 (2.7) | 812 (3.5) | 285 (7.0) | 393 (2.2) | |||

| Ejection fraction ≤50% | 4350 (56.4) | 1638 (67.3) | 2559 (51.2) | <0.001 | 9382 (55.7) | 7068 (52.3) | 1964 (72.6) | <0.001 | 0.33 |

| 2nd–3rd degree atrioventricular block | 442 (3.4) | 237 (5.2) | 169 (2.3) | <0.001 | 629 (2.5) | 213 (4.9) | 376 (2.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 348 (3.1) | 172 (4.5) | 161 (2.4) | <0.001 | 346 (1.6) | 133 (3.6) | 202 (1.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Reinfarction | 249 (2.0) | 120 (2.7) | 106 (1.4) | <0.001 | 385 (1.6) | 120 (2.8) | 238 (1.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Therapy at discharge | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Aspirin | 10 966 (86.1) | 3591 (79.9) | 6740 (91.0) | <0.001 | 22 570 (90.9) | 3565 (82.1) | 17 603 (93.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Other platelet inhibitor | 8344 (65.5) | 2351 (52.3) | 5601 (75.7) | <0.001 | 18 913 (76.1) | 2567 (59.2) | 15 338 (81.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| β-blockers | 10 509 (82.6) | 3473 (77.4) | 6419 (86.7) | <0.001 | 21 814 (87.9) | 3436 (79.2) | 17 001 (90.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 6710 (52.8) | 2089 (46.5) | 4263 (57.7) | <0.001 | 15 123 (61.0) | 2224 (51.3) | 12 123 (64.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 1026 (10.1) | 427 (12.2) | 572 (9.1) | <0.001 | 1658 (8.4) | 414 (12.3) | 1198 (7.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Statins | 8863 (69.7) | 2521 (56.2) | 5891 (79.6) | <0.001 | 20 475 (82.5) | 280 (64.8) | 16 524 (87.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Outcome | |||||||||

| In-hospital mortality | 1422 (11.0) | 849 (18.5) | 379 (5.1) | <0.001 | 1380 (5.5) | 675 (15.3) | 494 (2.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| One year mortality | 2473 (21.0) | 1419 (33.6) | 773 (11.5) | <0.001 | 2657 (11.7) | 1226 (30.2) | 1139 (6.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Long-term mortality§ | 5041 (20.1) | 2368 (51.6) | 1505 (20.2) | <0.001 | 4312 (33.4) | 2038 (46.2) | 2501 (13.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Table figures refer to counts (percentages) if not otherwise indicated.

*CKD defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 according to MDRD.

†Comparison between CKD and non-CKD.

‡Comparison between all men and all women.

§Median follow-up 1152 days.

Cath lab, catheterisation laboratory; CCU, coronary care unit; CG, Cockcroft-Gault formula; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study formula.

Acute MI was diagnosed using current guidelines during the years of inclusion16 17 if troponin T or I or two successive creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) values were above the 99th percentile for the reference population within 24 h of the index clinical event, or if the CK-MB value was twice above the decision limit. STEMI was defined as having a significant ST segment elevation on arrival-ECG together with the diagnosis of MI on discharge, that is, patients with left bundle branch block or pacemaker-ECG on admission were excluded. If a patient was registered with MI several times in SWEDEHEART, only the first occasion was counted.

Ethics

All patients for whom data are entered into the SWEDEHEART register are informed of their participation and their right to deny participation or have data removed later, in accordance to Swedish legislation. Data used for research purpose have all personal identifiers removed. The registry and the merging of registries are approved by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

Statistics

Continuous variables were summarised by their mean and SD, or median and IQR, as appropriate. Categorical variables were summarised by counts and percentages. Comparisons between different groups were performed by χ2 tests for categorical variables and by Student t test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. p Values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Crude and multivariable ORs with 95% CIs were calculated from logistic regression analyses in order to compare men and women as regards risk of having CKD. Variables incorporated in the model were: gender, age, smoking, previous MI, PCI, coronary artery bypass grafting, stroke, hypertension, DM, COPD, heart failure, PAD, dementia, cancer within 3 years, and therapy on arrival (aspirin, other platelet inhibitors, oral anticoagulants, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), statins, calcium-channel blockers (CCB), diuretics, digitalis and long-acting nitrates).

Crude and multivariable adjusted ORs and HRs with 95% CI were calculated using logistic and Cox proportional hazard regression analyses in order to evaluate the impact of eGFR on in-hospital and long-term mortality, respectively. Men and women were analysed separately. The same variables as above (except gender) were used with the addition of interventional hospital, year of inclusion, reperfusion therapy and Killip class regarding in-hospital mortality and also discharge therapy regarding long-term mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted for men and women in four CKD categories, according to MDRD and CG, respectively. Wilcoxon (Gehan) Statistics were used for comparisons between the CKD groups.

Finally, a possible interaction between gender and eGFR regarding mortality was evaluated incorporating an interaction term (ie, the product of gender and eGFR) into logistic and Cox regression models, respectively, together with gender and eGFR and all other covariates.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.18.0 (PASW Statistics V.18) software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Basic characteristics

A total of 37 991 patients were included in the analyses, 25 062 (66%) men and 12 929 (34%) women. Women were older, had lower weight, body mass index (BMI), heart rate and Killip class on admission. They also had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, COPD, PAD, previous stroke or dementia whereas men were more often smokers, had more often suffered from a previous MI and had more often been previously revascularised (table 1).

Complete data were available for 35 352 (93%) patients regarding MDRD and 26 586 (70%) patients regarding CG.

Patients with CKD, men and women, were older, had lower weight, BMI and systolic blood pressure but higher heart rate on admission, compared with patients with without CKD. The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, previous stroke, PAD, chronic heart failure or previous MI were higher in the patients with CKD but they were half as often smokers compared with the patients without CKD. Almost half of the CKD men and women were already on treatment with aspirin or β-blockers on admission. They had higher plasma glucose on admission and lower haemoglobin and cholesterol levels. They much more often had signs of heart failure including cardiogenic shock or pulmonary oedema and all complications during hospital care were more common among patients with CKD of both genders. Around 70% of the women and 50% of the men with CKD had left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <50%) compared with half of the men and women without CKD. They had a lower chance of reperfusion therapy or angiography during hospital care and less often received evidence-based cardiovascular therapies such as platelet inhibitors or statins at the time of discharge (table 1).

Differences between men and women in kidney function

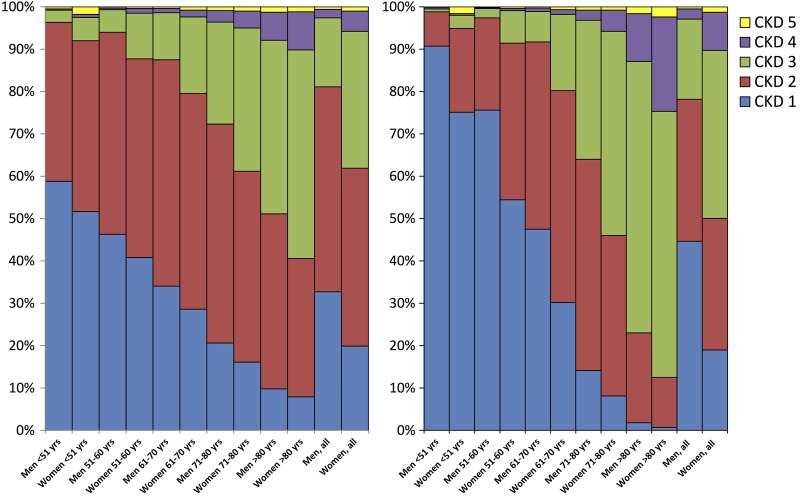

Mean s-creatinine on admission was higher in men whereas mean eGFR was lower in women regardless of formula. Mean eGFR was 69 and 66 mL/min in women compared with 81 and 88 mL/min in men, using MDRD and CG formulas, respectively (table 1). About 19% and 22% of men versus 38% and 50% of women had CKD according to the MDRD and CG formulas, respectively. Among men, 33% and 45% were in the best CKD stage compared with 20% and 19% among women according to both formulas. In the youngest group, more than 90% of men and 75% of women were in CKD stage 1 compared with only a few per cent of men and women in the oldest group according to CG (figure 1 and table 2).

Figure 1.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages according to Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD) (left) and Cockcroft-Gault (CG) (right) in five age-groups.

Table 2.

Prevalence of CKD stage 1–5 in women and men, MDRD and CG

| Women (n=12 929) | Men (n=25 062) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDRD study formula | (n=12 043) | (n=23 317) | |

| CKD stage 1 | 2400 (19.9) | 7623 (32.7) | <0.001 |

| CKD stage 2 | 5054 (42.0) | 11 279 (48.4) | |

| CKD stage 3 | 3891 (32.3) | 3801 (16.3) | |

| CKD stage 4 | 579 (4.8) | 464 (2.0) | |

| CKD stage 5 | 119 (1.0) | 150 (0.6) | |

| CG formula | (n=8794) | (n=17 792) | |

| CKD stage 1 | 1675 (19.0) | 7940 (44.6) | <0.001 |

| CKD stage 2 | 2731 (31.1) | 5964 (33.5) | |

| CKD stage 3 | 3487 (39.7) | 3366 (18.9) | |

| CKD stage 4 | 789 (9.0) | 428 (2.4) | |

| CKD stage 5 | 112 (1.3) | 94 (0.5) |

Data presented as numbers (percentages) if not otherwise noticed.

CG, Cockcroft-Gault; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease.

After adjustment for age, women had 1.6 and 2.2 times higher risk of having CKD with the MDRD and CG formula, respectively, which did not change after multivariable adjustment. The odds of being classified as having CKD were significantly higher when the CG was used instead of the MDRD formula. This result persisted even when cut-points for mild (eGFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) or severe (eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73 m2) CKD were used (table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of chronic kidney disease in women compared with men

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Age adjusted OR (95% CI) | Multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDRD (n=35 360) | |||

| Risk of eGFR<30 | 2.27 (2.04 to 2.55) | 1.43 (1.27 to 1.61) | 1.30 (1.11 to 1.47) |

| Risk of eGFR<60 | 2.64 (2,51 to 2.77) | 1.64 (1.56 to 1.74) | 1.58 (1.48 to 1.68) |

| Risk of eGFR<90 | 1.95 (1.85 to 2.06) | 1.32 (1.24 to 1.39) | 1.30 (1.22 to 1.38) |

| Cockcroft-Gault (n=26 586) | |||

| Risk of eGFR<30 | 3.78 (3.38 to 4.22) | 1.92 (1.71 to 4.04) | 1.85 (1.61 to 2.12) |

| Risk of eGFR<60 | 3.56 (3.37 to 3.76) | 2.20 (2.05 to 2.36) | 2.18 (2.02 to 2.36) |

| Risk of eGFR<90 | 3.43 (3.22 to 3.64) | 2.30 (2.13 to 2.49) | 2.29 (2.11 to 2.49) |

*Logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, previous myocardial infarction, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, previous coronary artery bypass grafting, chronic heart failure, previous stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, peripheral artery disease, previous cancer and therapy on arrival.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study formula.

Outcome, CKD versus non-CKD

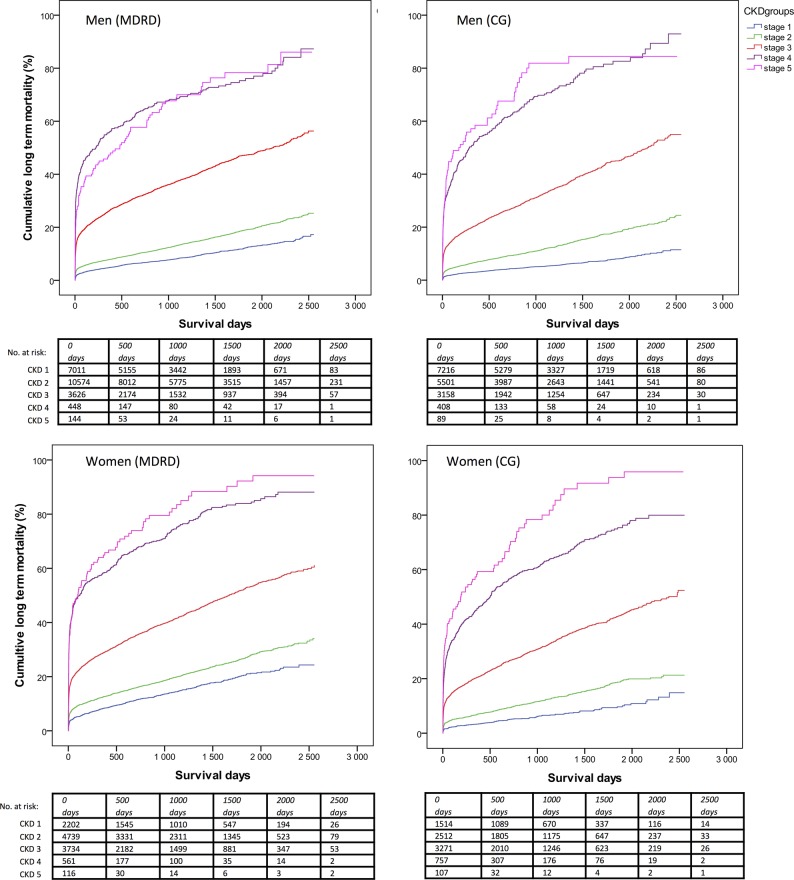

Nineteen per cent of women with CKD compared with 5% of women without CKD died during hospital care. The corresponding figures in men were 15% vs 3%. During follow-up, 52% of women with CKD died compared with 20% of women without CKD. Corresponding figures in men were 46% vs 13%. In both genders, after multivariable adjustments, in-hospital and long-term mortality gradually increased per 10 mL decline of eGFR and per incline in CKD stage according to both formulas (table 4 and figure 2). There was no significant interaction between gender and eGFR regarding in-hospital mortality (MDRD, p=0.07/CG, p=0.44) or long-term mortality (MDRD, p=0.83/CG, p=0.56).

Table 4.

Influence of reduced eGFR on short-term and long-term mortality

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Age adjusted OR/HR (95% CI) | Multivariable adjusted OR/HR* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men, MDRD (N=23 313) | |||

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.52 (1.48 to 1.56) | 1.35 (1.31 to 1.39) | 1.33 (1.18 to 1.28) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 6.73 (5.96 to 7.60) | 3.41 (2.99 to 3.89) | 2.59 (2.19 to 3.07) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=7623) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=11 277) | 2.25 (1.82 to 2.77) | 1.50 (1.21 to 1.85) | 1.38 (1.07 to 1.77) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3797) | 9.50 (7.73 to 11.68) | 3.79 (3.04 to 4.72) | 2.76 (2.12 to 3.60) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=612) | 28.92 (22.50 to 37.17) | 11.30 (8.66 to 14.75) | 7.23 (5.18 to 10.09) |

| Long-term mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.36 (1.34 to 1.38) | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.21) | 1.09 (1.07 to 1.11) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 4.29 (4.06 to 4.55) | 2.16 (2.02 to 2.30) | 1.57 (1.43 to 1.72) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=7623) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=11 277) | 1.63 (1.50 to 1.78) | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.17) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.22) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3797) | 5.19 (4.75 to 5.67) | 1.99 (1.81 to 2.19) | 1.56 (1.37 to 1.77) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=612) | 13.27 (11.76 to 14.97) | 5.03 (4.43 to 5.71) | 2.55 (2.12 to 3.06) |

| Women, MDRD (N=12 039) | |||

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.42 (1.38 to 1.46) | 1.29 (1.25 to 1.33) | 1.28 (1.23 to 1.33) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 4.24 (3.73 to 4.82) | 2.57 (2.25 to 2.94) | 2.01 (1.69 to 2.38) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=2400) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=5054) | 1.76 (1.37 to 2.26) | 1.22 (0.94 to 1.57) | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.71) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3887) | 5.14 (4.06 to 6.52) | 2.42 (1.89 to 3.10) | 1.96 (1.45 to 2.66) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=697) | 15.83 (12.10 to 20.72) | 7.31 (5.52 to 9.68) | 5.62 (3.95 to 8.00) |

| Long-term mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.33 (1.31 to 1.35) | 1.20 (1.18 to 1.22) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.14) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 3.10 (2.91 to 3.31) | 1.87 (1.75 to 2.01) | 1.47 (1.34 to 1.62) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=2400) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=5054) | 1.44 (1.28 to 1.62) | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.11) | 1.05 (0.89 to 1.23) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3887) | 3.47 (3.10 to 3.88) | 1.61 (1.44 to 1.81) | 1.37 (1.17 to 1.61) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=697) | 9.22 (8.08 to 10.54) | 4.10 (3.57 to 4.70) | 2.79 (2.30 to 3.39) |

| Men, CG (N=17 792) | |||

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.51 (1.46 to 1.56) | 1.36 (1.31 to 1.42) | 1.29 (1.23 to 1.36) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 7.92 (6.71 to 9.35) | 3.15 (2.56 to 3.89) | 2.49 (1.95 to 3.17) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=7940) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=5962) | 2.86 (2.15 to 3.80) | 1.61 (1.19 to 2.19) | 1.48 (1.05 to 2.08) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3363) | 11.29 (8.70 to 14.66) | 3.91 (2.81 to 5.42) | 2.97 (2.05 to 4.31) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=521) | 36.47 (26.83 to 49.57) | 11.47 (7.86 to 16.74) | 7.07 (4.55 to 10.99) |

| Long-term mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.41 (1.39 to 1.43) | 1.21 (1.19 to 1.24) | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.13) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 5.43 (5.04 to 5.84) | 2.00 (1.82 to 2.19) | 1.43 (1.27 to 1.60) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=7940) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=5962) | 2.32 (2.07 to 2.60) | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.32) | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.37) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3363) | 7.20 (6.47 to 8.01) | 2.00 (1.74 to 2.30) | 1.53 (1.29 to 1.82) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=521) | 22.75 (19.81 to 26.12) | 5.64 (4.75 to 6.70) | 2.60 (2.09 to 3.24) |

| Women, CG (N=8794) | |||

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.53) | 1.29 (1.23 to 1.36) | 1.22 (1.14 to 1.30) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 5.52 (4.46 to 6.84) | 2.28 (1.78 to 2.92) | 1.87 (1.40 to 2.49) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=1675) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=2731) | 2.25 (1.41 to 3.59) | 1.26 (0.78 to 2.04) | 1.32 (0.73 to 2.36) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3485) | 7.42 (4.85 to 11.39) | 2.47 (1.54 to 3.96) | 2.09 (1.17 to 3.73) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=900) | 20.38 (13.12 to 31.66) | 5.23 (3.15 to 8.70) | 3.51 (1.87 to 6.56) |

| Long-term mortality | |||

| Per 10 mL/min decline | 1.43 (1.40 to 1.46) | 1.26 (1.23 to 1.30) | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.19) |

| CKD compared with non-CKD | 4.55 (4.11 to 5.04) | 2.00 (1.78 to 2.25) | 1.71 (1.47 to 1.99) |

| CKD stage 1 (n=1675) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| CKD stage 2 (n=2731) | 1.93 (1.57 to 2.38) | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.41) | 1.38 (1.05 to 1.82) |

| CKD stage 3 (n=3485) | 5.71 (4.72 to 6.92) | 2.04 (1.64 to 2.53) | 2.17 (1.64 to 2.87) |

| CKD stage 4–5 (n=900) | 15.41 (12.62 to 18.82) | 4.26 (3.37 to 5.39) | 3.03 (2.23 to 4.11) |

*Adjusted for age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, previous MI, previous PCI, previous CABG, chronic heart failure, previous stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, peripheral artery disease, previous cancer and therapy on arrival, and, regarding long-term mortality analyses, also therapy at discharge.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CG, Cockcroft-Gault; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study formula; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves per chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages, women and men. Comparisons between CKD groups, Wilcoxon (Gehan) Statistics, p<0.001 for all comparisons except between CKD 4 and 5 in men (p=0.40 and 0.30, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD) and Cockcroft-Gault (CG), respectively).

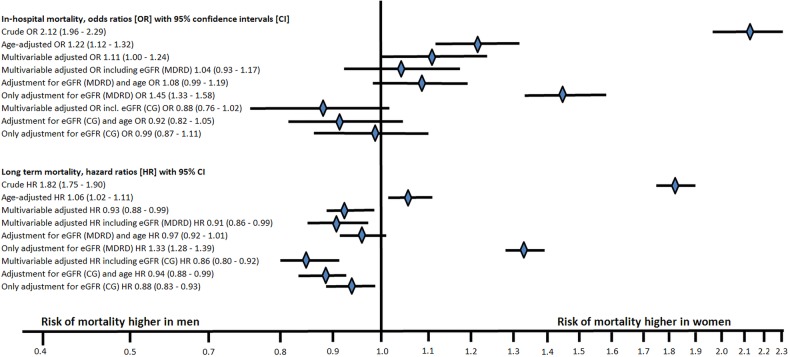

Outcome, women versus men

Women had more than doubled in-hospital and almost doubled long-term mortality than men. After adjustment for age, women still had 22% higher risk of in-hospital and 6% higher risk of long-term mortality. After multivariable adjustments including all confounders except kidney function, women still had 11% higher risk of in-hospital mortality but men had 7% higher risk of long-term mortality. If eGFR according to any of the formulas was also included, there was no longer a gender difference regarding in-hospital mortality, and women had a lower risk of long-term mortality. Adjusting for eGFR according to CG alone was enough to eradicate the higher risk in women, both short-term and long term, and changed the OR and HR more than the multivariable analyses that did not include kidney function (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Logistic and Cox proportional hazard regression models of in-hospital and long-term mortality. OR and HR with 95% CIs, women versus men (CG, Cockcroft-Gault; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study).

Sensitivity analysis

We also performed analyses on the limited population where CG was possible to estimate (70%=26 586). The results were very similar (see online supplementary tables S1–S4).

Discussion

The key findings in this study were that the prevalence of CKD in women with STEMI was very high and female gender was independently associated with CKD at admission in STEMI. In addition, reduced kidney function per 10 mL/min decline in eGFR regardless of the formula used was a strong and independent risk factor for short-term and long-term mortality in both genders without a significant gender difference in prognostic impact. Reduced GFR appeared to be an important reason why women had doubled mortality compared with men with STEMI.

Earlier studies have shown that in-hospital mortality varies from 1% in patients with normal kidney function (CKD stage 1) to 12–35% in those with severe renal dysfunction (CKD stage 4–5).2 6 CKD, defined as eGFR below 60 mL/min, has also been shown to be more common in patients with MI with prevalence around 30%1 2 6 compared with 6–8% in the general population.18 19 We found a remarkably high prevalence of CKD in women with STEMI. According to the Health Survey of Nord-Trondelag County (HUNT II) study, 5.7% of women and 3.6% of men in the general Nordic population have CKD stage 3–4 according to MDRD.18 The corresponding figures in our cohort were 38% and 19% of women and men, respectively. If we instead used the CG formula, which has been shown to better predict outcome in patients with MI than MDRD,9 as many as half of the women had CKD compared with 22% in men. There was a remarkable impact of age on CKD prevalence, especially when CG was used (figure 1).

Thus we thought it important to analyse the association between eGFR and outcome in both genders. Although women with STEMI have a worse outcome than men,10–12 few studies have investigated the role of renal impairment. Two small single-centre studies, one including mixed patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing coronary angiography and one including patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI, found a very high prevalence of CKD in women, based on the MDRD formula (67% vs 70%). Even more remarkable was that both studies found a stronger prognostic impact of CKD in women compared with men,13 20 something that we could not confirm in our study. We found no interaction between gender and eGFR with either of the formulas, neither on short-term nor long-term mortality. After multivariable adjustment, there was approximately 10% and 30% increased risk of short-term and long-term mortality per 10 mL decline in eGFR in both genders with both formulas. A possible explanation for the contradictory findings compared with the previous studies could be the higher prevalence of CKD in women compared with the present study, and differences in comorbidities and multivariate adjustments. In the STEMI study, there were few men with advanced CKD and thus few events in this group, which could explain the discrepant results. As both these previous studies were small, their findings could also be a matter of chance. The magnitude of the present study gave us better power to explore the influence of renal function in relation to gender.

In the present study, women had doubled in-hospital mortality compared with men. After adjusting for baseline differences including 27 covariates, women still had 11% higher risk of in-hospital mortality, consistent with previous findings.10–12 When eGFR according to any of the two formulas was adjusted for, there was no longer any gender difference in early mortality. In fact, adjusting for eGFR according to CG alone reduced the OR of in-hospital death from 2.12 (95% CI 1.96 to 2.29) to 0.99 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.11). Further adjustment did not alter the results substantially. Regarding long-term mortality, the same pattern was seen.

The higher prevalence of CKD in women could thus explain, to a great extent, the gender difference in mortality. It is likely, by adjusting for renal function alone, that several more adjustments can be made, as many risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, and especially age, covary with renal function both in men and women.1 6 The difference in adjustments was more pronounced with the CG formula than with the MDRD formula. Even though the two renal function equations both incorporate age in the equation, they handle the variables differently mathematically. In the present study, we could show that prognosis following an MI, both short-term and long term, is better described by the CG formula in men and women, and this is consistent with previous studies.9 It is, however, unknown which of the two formulas better reflects the true underlying renal function in the STEMI population. The most accurate way to measure kidney function is to measure GFR with an injected exogenous marker such as, for example, iohexol. In clinical practice, this is too cumbersome and, instead, estimating GFR has become routine practice. Neither of the two most common formulas were developed for cardiac patients. The CG formula was developed in the 1970s from a cohort of 249 men treated for a variety of diseases at medical wards7 and the MDRD formula was developed in the 1990s from a cohort of 1628 patients with CKD of both genders.8 They differ somewhat in their estimations in populations with varying gender, age and weight, and are recommended for different purposes: CG for dose adjustments, MDRD for detection of CKD. In spite of MDRD being developed on both genders but CG only in men, it has been shown that the relative error (bias) of CG predictions is associated with age and BMI but not with gender, whereas MDRD has been found to underestimate GFR in women. Equations for prediction of kidney function include a correction factor that lowers the prediction in women to compensate for the gender-dependent difference in creatinine (ie, muscular mass). The difference in muscular mass between men and women was found to be adequately predicted by the CG but overestimated by MDRD according to a study by Cirillo et al.21 In the same study, the authors hypothesise that the strong influence on renal function using the CG formula could partly be due to an overestimation of the association of ageing with decline of muscular mass. This could be an additional factor explaining the very high prevalence of CKD in women in our study, as they are clearly older than the men.

The reason for the poor outcome in patients with concomitant STEMI and CKD is multifactorial.22 It is well known that patients with CKD have a higher prevalence of risk factors such as DM and hypertension.23 Owing to the lower renal function in women, a higher proportion of women compared with men are at risk of contrast-induced nephropathy after PCI. Undertreatment with less reperfusion in women than men with CKD in our study (53.7% vs 84.3% in women and men, respectively) and other evidenced-based therapies also contribute to the reduced survival.24–26 This gender difference in evidence-based STEMI treatment has been shown before, even in the modern era.27 As an increased risk of major bleeding has been found in women treated with fibrinolytics,28 and CKD is also a predictor of bleeding,29 a fear of these dreadful complications may explain some of the observed difference. Other potential explanations could be the longer delay times in women and a higher prevalence of non-obstructive CAD.27 In our study, the chance of having a coronary angiography performed as well as other evidence-based therapies was lower in patients with CKD, something we adjusted for in the multivariate analysis. The lower use of invasive therapies could be explained by scarce evidence-based data, and a lack of proven efficiency in this group of patients. It is also unknown to what extent CKD was identified in patients with STEMI. The lack of recognition of CKD could represent a missed opportunity for dose adjustment of medications. Many patients with CKD and STEMI may have been treated without any dose-reduction in, for example, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, with more bleeding events as a consequence. It is possible that more women were exposed to higher doses, as they are often older and weigh less. In addition, CKD is associated with several metabolic abnormalities, such as oxidative stress, hypoalbuminaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia, hyperfibrinogenaemia, insulin resistance, lipid abnormalities, inflammation and derangements in the calcium–phosphate homeostasis, all possibly contributing to an excessive cardiovascular risk.30–34

Conclusion

Impaired renal function is extremely common in women with STEMI—in fact, half of all women with STEMI had at least moderate renal dysfunction. This is far more common than in the general population. The presence of CKD indicated doubled risk of in-hospital mortality in both genders, and reduced eGFR was found to be a strong and independent risk factor for early and late mortality with equal prognostic impact in both genders. Reduced eGFR appeared to be an important reason why women with STEMI had doubled mortality compared with men with STEMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all participating hospitals for their help and cooperation, and for contributing data to the SWEDEHEART registry.

Footnotes

Contributors: SSL was responsible for the conception and design of the study, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. JA, KS and ES were responsible for the conception and design of the study, critically revised the manuscript and added important intellectual content. MF critically revised the manuscript from a statistical perspective and added intellectual content. All the authors approved the submission of the manuscript.

Funding: The SWEDEHEART register is supported by the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Swedish Society of Cardiology, and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The present study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee in Uppsala.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code and data set are available from the authors whenever needed.

References

- 1.Anavekar NS, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ et al. Relation between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1285–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa041365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santopinto JJ, Fox KA, Goldberg RJ et al. Creatinine clearance and adverse hospital outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: findings from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Heart 2003;89:1003–8. 10.1136/heart.89.9.1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson CM, Dumaine RL, Gelfand EV et al. Association of glomerular filtration rate on presentation with subsequent mortality in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; observations in 13,307 patients in five TIMI trials. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1998–2005. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadeghi HM, Stone GW, Grines CL et al. Impact of renal insufficiency in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003;108:2769–75. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103623.63687.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Suwaidi J, Reddan DN, Williams K et al. Prognostic implications of abnormalities in renal function in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2002;106:974–80. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000027560.41358.B3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox KA, Antman EM, Montalescot G et al. The impact of renal dysfunction on outcomes in the ExTRACT-TIMI 25 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:2249–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976;16:31–41. 10.1159/000180580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:461–70. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szummer K, Lundman P, Jacobson SH et al. Cockcroft-Gault is better than the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study formula at predicting outcome after a myocardial infarction: data from the Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART). Am Heart J 2010;159:979–86. 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD et al. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:226–32. 10.1056/NEJM199907223410402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mega JL, Morrow DA, Ostor E et al. Outcomes and optimal antithrombotic therapy in women undergoing fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2007;115:2822–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.679548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Champney KP, Frederick PD, Bueno H et al. NRMI Investigators. The joint contribution of sex, age and type of myocardial infarction on hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Heart 2009;95:895–9. 10.1136/hrt.2008.155804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sederholm Lawesson S, Todt T, Alfredsson J et al. Gender difference in prevalence and prognostic impact of renal insufficiency in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart 2011;97:308–14. 10.1136/hrt.2010.194282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jernberg T, Attebring MF, Hambraeus K et al. The Swedish Web-system for enhancement and development of evidence-based care in heart disease evaluated according to recommended therapies (SWEDEHEART). Heart 2010;96:1617–21. 10.1136/hrt.2010.198804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.[No authors listed] Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1502–13. 10.1053/euhj.2000.2305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2525–38. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallan SI, Coresh J, Astor BC et al. International comparison of the relationship of chronic kidney disease prevalence and ESRD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:2275–84. 10.1681/ASN.2005121273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007;298:2038–47. 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen R, Kumar S, Timmis A et al. Comparison of the relation between renal impairment, angiographic coronary artery disease, and long-term mortality in women versus men. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:630–2. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirillo M, Anastasio P, De Santo NG. Relationship of gender, age, and body mass index to errors in predicted kidney function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:1791–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfh962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCullough PA. Why is chronic kidney disease the “spoiler” for cardiovascular outcomes? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:725–8. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02955-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levey AS, Beto JA, Coronado BE et al. Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: what do we know? What do we need to learn? Where do we go from here? National Kidney Foundation Task Force on Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;32:853–906. 10.1016/S0272-6386(98)70145-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong JA, Goodman SG, Yan RT et al. Temporal management patterns and outcomes of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes in patients with kidney dysfunction. Eur Heart J 2009;30:549–57. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shlipak MG, Heidenreich PA, Noguchi H et al. Association of renal insufficiency with treatment and outcomes after myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:555–62. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szummer K, Lundman P, Jacobson SH et al. SWEDEHEART. Relation between renal function, presentation, use of therapies and in-hospital complications in acute coronary syndrome: data from the SWEDEHEART register. J Intern Med 2010;268:40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawesson SS, Alfredsson J, Fredrikson M et al. Time trends in STEMI—improved treatment and outcome but still a gender gap: a prospective observational cohort study from the SWEDEHEART register. BMJ open 2012;2:e000726 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds HR, Farkouh ME, Lincoff AM et al. Impact of female sex on death and bleeding after fibrinolytic treatment of myocardial infarction in GUSTO V. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2054–60. 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2003;24:1815–23. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00485-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fliser D, Pacini G, Engelleiter R et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are already present in patients with incipient renal disease. Kidney Int 1998;53:1343–7. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stenvinkel P, Heimburger O, Paultre F et al. Strong association between malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 1999;55:1899–911. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baber U, de Lemos JA, Khera A et al. Non-traditional risk factors predict coronary calcification in chronic kidney disease in a population-based cohort. Kidney Int 2008;73:615–21. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M et al. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 2005;112:2627–33. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bostom AG, Shemin D, Lapane KL et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperfibrinogenemia, and lipoprotein (a) excess in maintenance dialysis patients: a matched case-control study. Atherosclerosis 1996;125:91–101. 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05865-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]