Abstract

Introduction

A number of jurisdictions internationally have policies requiring schools to implement healthy canteens. However, many schools have not implemented such policies. One reason for this is that current support interventions cannot feasibly be delivered to large numbers of schools. A promising solution to support population-wide implementation of healthy canteen practices is audit and feedback. The effectiveness of this strategy has, however, not previously been assessed in school canteens. This study aims to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an audit and feedback intervention, delivered by telephone and email, in increasing the number of school canteens that have menus complying with a government healthy-canteen policy.

Methods and analysis

Seventy-two schools, across the Hunter New England Local Health District in New South Wales Australia, will be randomised to receive the multicomponent audit and feedback implementation intervention or usual support. The intervention will consist of between two and four canteen menu audits over 12 months. Each menu audit will be followed by two modes of feedback: a written feedback report and a verbal feedback/support via telephone. Primary outcomes, assessed by dieticians blind to group status and as recommended by the Fresh Tastes @ School policy, are: (1) the proportion of schools with a canteen menu containing foods or beverages restricted for sale, and; (2) the proportion of schools that have a menu which contains more than 50% of foods classified as healthy canteen items. Secondary outcomes are: the proportion of menu items in each category (‘red’, ‘amber’ and ‘green’), canteen profitability and cost-effectiveness.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained by from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee. The findings will be disseminated in usual forums, including peer-reviewed publication and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12613000543785.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a major public health concern worldwide which presents immediate health risks for children and long-term health risks by tracking into adulthood.1 Globally, the prevalence of child overweight and obesity is highest in middle and high-income countries.2 In Australia, the USA and European countries, up to 20–30% of school-aged children are overweight or obese.3–5 A key driver of unhealthy weight gain in children is poor diet, specifically regular overconsumption of high caloric foods, saturated fats and sugar.6 7

Schools play an important role in establishing healthy eating behaviours in children.8–10 Schools offer intensive contact and multiple opportunities to promote healthy nutrition.10 Implementation of healthy nutrition policies in schools, to improve the food environment, has been successful in improving food consumption behaviours.8 One systematic review found that healthy nutrition policies in schools that regulate the amount of saturated fat and promote greater availability of fruit and vegetables in canteens have positive effects on student diet.8 In the five identified studies that implemented nutritional guidelines in schools, there was a 2–11% reduction in total fat intake and between 0.3 and 0.4 serve increase in children's daily fruit and vegetable intake.8 Another two studies applying a regulatory policy to restrict unhealthy food sales observed a statistically significant reduction in the sale of sweetened drinks (−28%) and chips (−16%) at 6 months and at 2 years after implementation (−2.6%).8

The implementation of healthy nutrition policies in school canteens internationally is suboptimal, even when the policy is mandated by government.11–14 In Australia, governments have released a range of nutritional policies to improve the types of foods and drinks available to students. The New South Wales, Fresh Tastes @ School Healthy Canteen Strategy, introduced in 2005, requires all government schools to restrict the regular sale of unhealthy foods and beverages (known as red or banned items) from canteens and for healthy food options (known as green items) to represent the majority of items listed on menus.15 Despite this, an audit of government schools in New South Wales in 2012 revealed all canteens sold restricted products and no menus contained sufficient healthy options.16 In the state of Victoria, Australia, evaluation of a similar policy, 3 years after its introduction, found that nearly 40% of surveyed menus contained restricted items.17

A possible reason why schools do not implement healthy canteen policies is the paucity of evidence regarding effective strategies to improve implementation in this setting.18 A systematic review by Rabin et al18 identified just five studies of interventions to improve implementation of obesity prevention programmes within the school setting. No study addressed the implementation of healthy canteen policy. All included studies were conducted in a small number of schools and exhibited significant methodological flaws; only one study used a comparative design.19 More methodologically rigorous trials of interventions that can be delivered on a broader scale to support healthy canteen policy implementation in schools are required.

Cost-effective intervention models that target barriers specific to canteen operations are required to support schools to implement healthy canteen policy. Barriers to implementing such policy are likely to vary depending on school size, location, demographics and canteens opening times. Known barriers include: difficulties understanding complex policy recommendations, classifying foods in accordance with nutrient guidelines, and sourcing healthy foods.16 20–22 These barriers combined with constantly changing nutritional content of commercially provisioned foods22 suggest that implementation support needs to be delivered on an ongoing basis to assist school canteens compose healthy seasonal menus.16 21 However, the cost of current face-to-face models used to support schools means many schools miss out on continued engagement.20 22

A promising strategy that could be used to continually support schools implement healthy canteen policies is audit and feedback (also known as performance feedback). Audit and feedback has been used for organisational behaviour management in various forms and settings,23 particularly clinical settings.24 A Cochrane systematic review24 25 found moderate evidence that audit and feedback can positively influence clinical behaviours of healthcare professionals. Following audit and feedback, desired practice behaviour improved by up to 17% on baseline behaviour.24 25 The magnitude of this effect is greater when: baseline adherence is low, feedback frequency is higher, feedback is provided with antecedent stimuli and using multiple modes of feedback.23 25 However, there have been no randomised controlled trials conducted of audit and feedback interventions combining all of these features.25

Audit and feedback can be delivered in a number of ways. When delivered via mediated (non-face to face) modalities (eg, telephone, email, post), support can be delivered to more schools frequently and for longer periods at reduced cost.16 23 25 The flexibility in such delivery may also more adequately cater for schools in rural communities and with canteens that open less often.21 Audit and feedback delivered via telephone and/or email presents the potential for such interventions to be highly effective in assisting all schools to implement healthy canteen policies. However, there have been no controlled studies conducted to investigate the effectiveness of audit and feedback intervention in the school canteen setting. To address this evidence gap, we designed the first ever randomised controlled trial of a canteen audit and feedback intervention (the Canteen Audit and Feedback Effectiveness study—CAFÉ) to support primary schools to implement a healthy canteen policy (The NSW Healthy School Canteen Policy—Fresh Taste @ School).

Specifically, the primary aims of the study are to determine if, compared to usual service support, a multicomponent menu audit and performance feedback intervention delivered by telephone and email results in: (1) a significantly reduced proportion of schools listing ‘red’ or ‘banned’ foods and beverages on the canteen menu, and (2) a significantly increased proportion of schools with more than 50% of items on their menu classified as ‘green’ items. Secondary aims are to: assess the effect of the intervention on menu composition (ie, the proportion of menu items categorised as ‘red’, ‘amber’ or ‘green’) and on canteen profitability, and to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Methods and analysis

Design

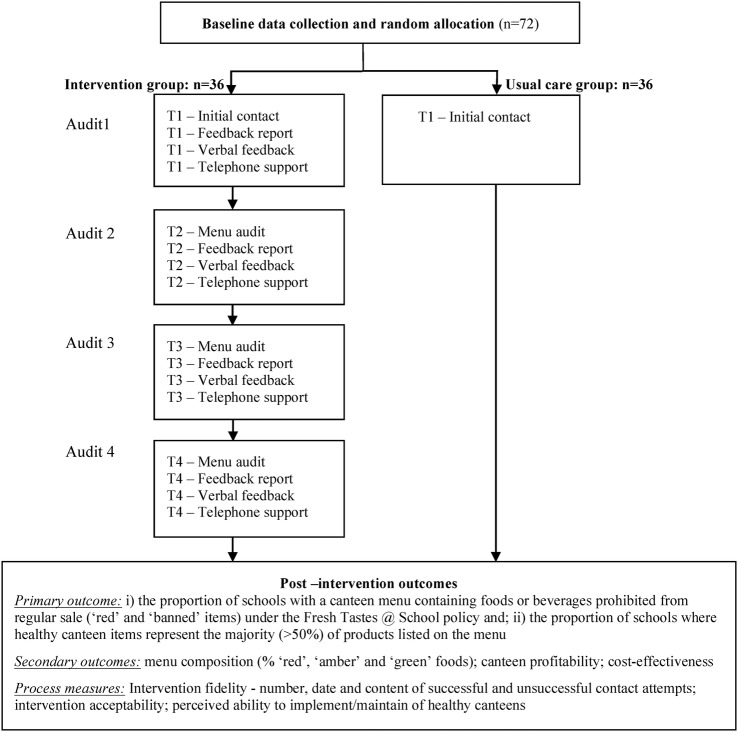

CAFÉ is a single-blind, randomised controlled trial (ACTRN12613000543785) of a tailored multicomponent feedback intervention delivered by telephone and email over 12 months. A total of 72 consenting government, catholic or independent primary schools in rural and remote regions of the Hunter New England Local Health District in NSW Australia will be randomised to an intervention or control group (figure 1). Primary schools in NSW enrol students aged 5–12 years of age. Intervention schools will have their canteen menu audited by trained dieticians, and then provided with two modes of feedback: a written feedback report and telephone feedback calls. The control group will be provided with usual service support. Study outcome measures will be assessed at the organisational level and include blind menu assessments conducted at baseline and postintervention.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Study population and inclusion criteria

Primary schools (government, catholic and independent) located in the New England Region of New South Wales or in rural or remote communities of the Hunter Region of New South Wales, with an operational school canteen will be invited to participate. Schools with canteens open at least 1 day/week over the school year will be eligible to participate. Schools with canteen menus assessed as compliant with Fresh Taste @ School policy at baseline data collection will be ineligible (ie, no red or banned items and more than 50% green items). Schools catering exclusively for children requiring specialist care, and schools without a canteen will be ineligible. Schools will not be excluded based on other characteristics (eg, size and socioeconomic indicators).

Recruitment and randomisation procedures

All eligible schools with an operational canteen in the Local Health District will be invited to complete a baseline telephone interview. Canteens will also be asked to provide the current canteen menu to the research team for assessment. Trained dieticians will assess the menu for compliance with the policy to determine eligibility for the study. Consenting eligible schools will be randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group in a 1:1 ratio by an investigator not involved in data collection or intervention delivery, using a computer-generated randomisation schedule. The randomisation schedule will be generated a priori by the investigator using the random number function in EXCEL.

Policy context

In 2005, the NSW government introduced the Fresh Tastes @ School Healthy Canteen Strategy as a key component to an action plan to prevent childhood obesity. Under the strategy, canteens are required to: classify all food and beverage items on the menu as ‘red’, ‘amber’ or ‘green’ based on their nutritional properties (tables 1 and 2); remove ‘red’ items from regular everyday sale; ‘fill the menu’ with ‘green’ items; and not have ‘amber’ items classified as ‘amber’ dominate (ie, comprise more the 50% of) the menu. In 2007, the strategy was extended by banning the sale of sugar sweetened drinks (>300 kJ or >100 mg sodium per serve; table 2).

Table 1.

Fresh Tastes @ School NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy

| ‘Red’ Occasional foods No More Than Twice Per School Term |

‘Amber’ Select Carefully Do Not Let These Foods Dominate The Menu |

‘Green’ Fill the menu Encourage And Promote These Foods |

|---|---|---|

| These foods are not recommended for sale in canteens because they are energy dense, lack adequate nutritional value and are high in saturated fat and/or salt and/or sugar Examples include confectionary and deep-fried foods as well as many premium ice-creams, savoury snacks, cakes and pastries will also fall into the RED category. These products need to be assessed against the occasional foods criteria (table 2). Sugar-Sweetened Drinks Any sugar-sweetened drink that exceeds the criteria below is classified as BANNED and therefore is not allowed for sale in the canteen |

These foods contain some valuable nutrients; however they also contain moderate amounts of saturated fat and/or salt and/or sugar and are not recommended in large serving sizes as they can contribute excess energy. Examples include:

|

These foods are good sources of nutrients contain less saturated fat and/or salt and/or sugar and help to avoid an intake of excess energy. Examples include:

|

Table 2.

Occasional food criteria

| Hot food assessed per 100 g | Energy (KJ) | Saturated fat (g) | Sodium (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Savoury pastries, pasta, pizzas, over-baked potato products, spring rolls, fried rice and noodles | >1000 | >5 | >400 |

| Crumbed & coated foods e.g. patties, ribs, chicken products and sausages/frankfurts | >1000 | >5 | >700 |

| Snack foods/drinks assessed per serve | Energy | Saturated fat | Sodium | Fibre (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar-sweetened drinks and ices | >300 | >100 | ||

| Snack food bars and sweet biscuits | >600 | >3 | <1 | |

| Savoury snack foods and biscuits | >600 | >3 | >200 | |

| Ice creams, milk-based ice confections and airy desserts | >600 | >3 | ||

| Cakes, muffins and sweet pastries, etc | >900 | >3 | <1.5 |

Intervention process

The intervention is designed to be delivered by telephone and email to reduce costs and facilitate wider participation. Schools will be allocated a trained school support officer (teacher or dietician) who will deliver the intervention to the school. Intervention schools will receive initial introductory contact from school support staff to clarify the nature of the programme and confirm participation. To improve canteen manager engagement up to one face-to-face visit will be conducted. Schools will be asked to provide menus by fax, email or mail. Baseline menus will be used for the first intervention audit. Canteen menus will be audited by trained dieticians using an agreed coding system (‘red’ amber’, ‘green’) based on the Fresh Tastes@School policy. The results of the menu audit will inform the content of a written feedback report. Written feedback reports will be delivered to the canteen manager by email (or by post if email is not available). Canteen managers will then receive a telephone feedback call (where possible within 1 week of sending the written feedback report) and a follow-up support call (approximately 2–4 weeks following the feedback call). School support officers will tailor the dose of the menu audit and feedback process based on: the time frame of the schools menu changes, the responsiveness of canteen manager to contacts and menu changes, and the need for subsequent menu changes. Canteens will be provided with at least two audit and feedback rounds to a maximum of four, over the school year (ie, four school terms). The tailoring of the intervention dose is considered pragmatic in nature, and is designed to examine the feasibility for ongoing implementation. All intervention processes will be recorded for each school.

Intervention content

The intervention content was developed based on a review of audit and feedback literature in other settings.23 25 Features suggested to improve the effectiveness of performance feedback in other settings will be included in the intervention.23 25 These include: greater than one audit and performance feedback; feedback from a reputable source (health service dieticians); multicomponent feedback (written and verbal delivered via email and telephone); and feedback which includes explicit targets for change based on agreed action plans developed by the canteen manager and support staff during the initial contacts.23 25

The performance feedback strategy is designed to address identified barriers to the implementation of healthy canteen policy. The provision of menu audits aims to address knowledge and resource barriers of school canteen staff to conduct regular menu reviews.16 Written and verbal feedback, aims to address knowledge barriers about complex policy recommendations and classifying foods.16 21 Telephone-based support aims to provide school canteens with accessible tailored assistance including goal setting (action planning) and problem solving to overcome local contextual issues preventing the composition of a healthy menu, for instance an influence of profit making,16 issues with provision of healthy foods or social resistance to change.21

The written feedback report will contain specific details about the compliance of the canteen menu with the Fresh Tastes @ School policy, suggestions for improved menu composition and supplementary resources. The content of the report and resource provision will be tailored based on the identified requirements to meet Fresh Tastes @ School policy. Feedback/support calls will involve discussion of the feedback report. The support officer conducting the call will clarify why foods listed on the menu were classified as ‘green’, ‘amber’, ‘red’ or ‘banned’ foods. During the feedback call, specific targets will be set and strategies devised (action plans) to improve menu composition to comply with Fresh Tastes @ School policy. Subsequent feedback/support calls will focus on monitoring and execution of agreed actions. Additional resources, such as ‘green’/‘amber’ recipes, snack ideas pamphlets and information on accessible alternatives to ‘red’ or ‘banned’ items will only be provided when required in the support cycle.

The control group will receive usual reactive support consisting of standard teacher development opportunities. In New South Wales, all schools (intervention and control) may have the opportunity to attend staff development opportunities about specific government policy (eg, Live Life Well @ School, Fresh Tastes @ School, Crunch&Sip) and/or be provided with miscellaneous resources relating to such policy.

Data collection

Schools characteristics, including school size, location, postcode (in order to determine school socioeconomic status), sector (government, catholic or independent), canteen manager type (paid/volunteer), number of canteen volunteers and the number of days the canteen operates will be captured prior to randomisation during the baseline telephone interview.

For primary and secondary outcomes assessment, schools will be asked to complete a telephone interview and then asked to provide the current canteen menu and relevant annual report containing canteen financial statements. A trained dietician will check returned menus for the completeness of information required to accurately classify items according to policy recommendations. When required, the dietician will contact school canteens by telephone to collect further nutrition information about menu items. A second trained dietician (blind to group) status will then independently classify all items according to the policy criteria (‘red’, ‘amber’ ‘green’). Classifications will be based on the Fresh Tastes @ School NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy Ready Reckoner of commonly sold foods in school canteens. A set of assumptions, created to standardise the procedure and assist with information gaps and ambiguous items, will be used to consistently classify ‘green’ and ‘amber’ items as Fresh Tastes @ School does not have criteria to differentiate between the two categories (eg, ‘green’ and ‘amber’).These assumptions were formulated in a consensus process involving a team of dieticians experienced in the implementation of the Fresh Tastes @ School and the research team. Throughout the study, the team of dieticians (including those involved with outcome assessment) will meet weekly to discuss and record agreed classifications of new, ambiguous menu items to ensure ongoing consistency of item coding.

Intervention process measures (see below) will be captured during telephone feedback and support calls, and in the follow-up telephone interview. These will be recorded into a school case report form and transcribed into an electronic database.

Study outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes measures for the trial are (1) the proportion of schools with a canteen menu containing foods or beverages restricted from regular sale (‘red’ and ‘banned’ items) under the Fresh Tastes @ School policy and; (2) the proportion of schools where healthy canteen items (‘green’) represent the majority (>50%) of products listed on the menu as recommended by the Fresh Tastes @ School policy. These will be assessed by audit of school menus at baseline and postintervention. Trained dieticians will code each menu item using the traffic light-based classification system recommended by the policy (previously described). Where additional nutritional information is not available by following attempts to contact the canteen, or where the policy fails to classify a certain food, the predetermined assumptions will be used to classify that food. All items will be counted to produce a total menu count. Total numbers of ‘green’, ‘amber’, ‘red’ and ‘banned’ items will be counted and converted to percentages. To ensure robustness of the primary outcome, menu classifications and counting will be double-checked by another trained dietician. Inconsistencies will be resolved by discussion. Where no consensus is reached, a third dietician will be consulted. To maintain blinding to group allocation at follow-up, menus will be audited using de-identified data containing only menu items and nutritional information.

Secondary outcomes

Menu composition

The proportion of menu items in each category (‘red’, ‘amber’, ‘green’) under the Fresh Tastes @ School policy will be determined based on menu audit.

Canteen profitability

Canteen profitability will be assessed using a direct self-reported measure of profit or loss in the previous financial year. In addition, canteen annual reports, including profit/loss statements from school annual reports, will be used to validate canteen profitability where available. In the case of a mismatch, data from annual reports will be used.

Cost-effectiveness

Intervention delivery costs will be calculated as staff time and cost of resources provided or used in the delivery of the audit and feedback programme. Cost implications for school canteens to implement a compliant menu will include: costs of menu changes calculated by assessing the total estimated budget impact on the canteen, including lost (or gained) revenue as the result of an added or removed item; and the cost of additional resources to implement or maintain the menu (eg, cost of additional preparation). This information will be estimated by the canteen manager and where possible, validated by profit/loss statements from school annual reports.

Process measures

All intervention processes will be logged. Information about the number, date, type and content of successful and unsuccessful contact attempts will be recorded in a case report form for each school. During the follow-up assessment interview, control schools will be asked about the number and type of incidental support contacts they receive, either from the Hunter New England Health staff or other organisations. At follow-up, canteen managers will also be asked about acceptability of the intervention (for intervention schools), and perceptions about their ability and confidence to implement and sustain a healthy canteen (all schools). To gain understanding about barriers to the support delivery, intervention schools and support officers will be questioned at follow-up regarding reasons for not adhering to action plans and the proposed service support.

Statistical considerations

Primary statistical analyses

The primary analysis will be assessed by comparing group differences at 12 months follow-up under an intention-to-treat approach. Primary outcomes will be compared using logistic regression models using all available data and adjusted for baseline values. The conclusions about effectiveness of the intervention will be based on between-group comparisons of both outcomes separately. The proportion of schools in each group with no red items, and the proportion with the majority (>50%) of menu items categorised as green will be presented with 95% CIs. Where an item is coded using an assumption in place of actual information, the school, menu item and assumption made will be recorded and considered in a sensitivity analysis. Multiple imputations will be performed as part of sensitivity analysis for schools not providing follow-up data.

Secondary statistical analyses

Longitudinal mixed models will be used to test treatment effect on secondary outcomes. Specific comparisons will be the effect of the intervention on menu composition (proportion of ‘red’, ‘amber’, ‘green’ foods listed in the menu) and canteen profitability (profit or loss to the nearest dollar). Economic analyses will be conducted to determine the cost-effectiveness of the intervention from the perspective of the health sector. A costing model will be developed, including the cost of the delivery of the intervention. A secondary analysis will entail a societal perspective in which cost implications on school canteens to implement a menu compliant with Fresh Tastes @ School will be estimated.

Sample size

Allowing for 15% compliance with Fresh Tastes @ School policy at follow-up in the comparison group, a sample of 36 schools in the intervention group and 36 in the control group will have 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 30% between schools in primary outcomes using a two-sided α of 0.05. No prior knowledge is available regarding a meaningful effect of audit and feedback in school canteens; so the effect size was based on consensus between study investigators.

Ethics and dissemination

The study adheres to National Health and Medical Research Council ethical guidelines for human research. The study has been approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. No. 11/03/16/4.05), University of Newcastle (Ref. No. H-2011-0210), NSW Department of Education and Communities (SERAP 2011111) and Armidale and Maitland Newcastle Catholic School Diocese. School principals and canteen managers will be invited to take part on a voluntary basis and will be able to discontinue participation at any time with no further explanation. The findings will be disseminated in usual dissemination forums, including peer-reviewed publication and conference presentations. School principals and canteen managers will be supplied with a letter detailing the results of the study. Study investigators will retain full control over the study data. No personal information is collected.

Discussion

This paper presents the design and rationale for the first randomised controlled trial of a multicomponent, telephone and email-based audit and feedback intervention to facilitate canteen policy adoption in schools. The study will determine if the audit and feedback intervention can reduce the proportion of schools selling restricted and unhealthy food items, and improve the proportion of schools with canteen menus dominated by healthy items. If shown to be effective, the strategy has potential to offer cost-effective and sustainable support to improve the school canteen food environment.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Christopher Williams at @cmwillow

Contributors: CMW, NN and LW designed the intervention. CMW, NN, TD, SLY, JW, SP, NL, RS, JP, KS, TS, PB, RJW and LW contributed to the design of the study and development protocols and materials. CMW drafted the manuscript. NN, TD, SLY, JW, SP, NL, RS, JP, KS, TS, PB, RJW and LW provided critical review of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: This work is supported by funding from the Hunter New England Local Health District and infrastructure support from the Hunter Medical Research Institute. LW holds an NHMRC research fellowship.

Competing interests: NN, LW and JW are investigators on a controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of an intensive implementation intervention to facilitate the adoption of a state-wide healthy canteen policy (ACTRN126090000966291), funded by the Australian Research Council.

Ethics approval: New South Wales, Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Singh A S, Mulder C, Twisk JWR et al. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008;9:474–88. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Organization Health. International classification of diseases. World Organ. Heal; 2010. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy L, King L, Espinel P et al. NSW Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (SPANS) 2010: Full Report. Sydney, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK et al. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. J Am Med Assoc 2012;307:483–90. 10.1001/jama.2012.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:176–88. 10.3109/09540261.2012.688195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commonwealth Scientific Industrial research Organisation (CSIRO). 2007 Australian national children's nutrition and physical activity survey-main findings. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Department of Health. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Headline Results from Years 1, 2 and 3 (combined) of the Rolling Programme 2008/09–2010/11. 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-headline-results-from-years-1-2-and-3-combined-of-the-rolling-programme-200809-201011

- 8.Jaime PC, Lock K. Do school based food and nutrition policies improve diet and reduce obesity? Prev Med (Baltim) 2009;48:45–53. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Disease: WHO Technical Report Series 916. Geneva, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Brainstorming meeting on the development of a framework on the Nutrition-Friendly Schools Initiative. Montreux: WHO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox MK, Gordon A, Nogales R et al. Availability and consumption of competitive foods in US public schools. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:S57–66. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter MA. Measuring the ‘obesogenic’ food environment in New Zealand primary schools. Health Promot Int 2004;19:15–20. 10.1093/heapro/dah103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crepinsek MK, Gordon AR, McKinney PM et al. Meals offered and served in US public schools: do they meet nutrient standards? J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:S31–43. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers IS, Ness a R, Hebditch K et al. Quality of food eaten in English primary schools: school dinners vs packed lunches. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:856–64. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NSW Department of Health & NSW Department of Education and Training. Fresh taste @ school, NSW healthy school canteen strategy: canteen menu planning guide. 1st edn Sydney, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardzejewska K, Tadros R, Baxter D. A descriptive study on the barriers and facilitators to implementation of the NSW (Australia) Healthy School Canteen Strategy. Health Educ J 2013;72:136–45. 10.1177/0017896912437288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Silva-Sanigorski A, Breheny T, Jones L et al. Government food service policies and guidelines do not create healthy school canteens. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011;35:117–21. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, Kerner JF et al. Dissemination and implementation research on community-based cancer prevention: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:443–56. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, Sanchez J et al. Prevention of the epidemic increase in child risk of overweight in low-income schools: the El Paso coordinated approach to child health. J Am Med Assoc 2005;159:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaycox LH. Challenges in the evaluation and implementation of school-based prevention and intervention programs on sensitive topics. Am J Eval 2006;27:320–36. 10.1177/1098214006291010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downs SM, Farmer A, Quintanilha M et al. From paper to practice: barriers to adopting nutrition guidelines in schools. J Nutr Educ Behav 2012;44:114–22. 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mâsse LC, Naiman D, Naylor P-J. From policy to practice: implementation of physical activity and food policies in schools. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:71 10.1186/1479-5868-10-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvero AM, Bucklin BR, Austin J. An objective review of the effectiveness and essential characteristics of performance feedback in organizational settings (1985–1998). J Organ Behav 2001;21:3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamtvedt G, Young J, Kristoffersen et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3):CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(6):CD000259 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]