Abstract

An orbital venous varix is rare and can present with diplopia, proptosis, or hemorrhage. Treatment can be challenging, especially if the varix is in a posterior location within the orbit, since surgical exposure becomes difficult. A few case reports have been published describing transcatheter embolization of an orbital varix with coils, direct percutaneous injection of n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue, and the percutaneous injection of bleomycin. We present a case of a symptomatic orbital venous varix of the left inferior ophthalmic vein successfully treated with transvenous endovascular sclerotherapy using a microcatheter balloon and bleomycin.

Keywords: Vascular Malformation, Orbit, Balloon

Background

An orbital venous varix is a rare lesion of the orbit, accounting for less than 1.3% of all orbital tumors.1 It is classified as primary or secondary, the latter acquired as a result of retrograde filling secondary to vascular abnormalities such as caroticocavernous fistula, dural arteriovenous fistula, or intracranial arteriovenous malformations. A primary orbital venous varix is thought to be congenital and typically manifests in the second or third decade.1 Presenting symptoms can include intermittent diplopia, proptosis, decreased visual acuity, and retro-orbital pain. These lesions are the most common cause of spontaneous orbital hemorrhage.2 Exacerbation of symptoms may occur with an increase in intraorbital pressure with straining or prone/stooping positioning. Acute symptoms may occur if the varix thromboses. Diagnosis and orbital imaging can be normal in a resting state but a provocative Valsalva maneuver or a prone position can elicit proptosis and engorgement of the varix.

We present a case of a symptomatic orbital varix of the left inferior ophthalmic vein in a 63-year-old man successfully treated with transvenous endovascular sclerotherapy using a microcatheter balloon and bleomycin over two sessions.

Case presentation

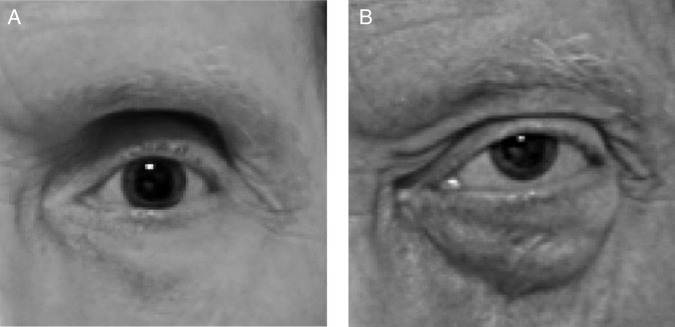

A 63-year-old man presented with intermittent proptosis and progressive worsening of vision loss in his left eye over 1 year. Further history indicated that he was probably having symptoms for more than a decade as he described difficulty focusing with his left eye when bending over (figure 1A, B). Ophthalmology evaluation noted left eye swelling and proptosis when bending over and 20/20 vision in the right eye compared with 20/50 in the left eye. After discussion of treatment options, we elected to pursue left orbital venography with possible transvenous and/or percutaneous sclerotherapy of the varix.

Figure 1.

A 63-year-old man with progressive loss of vision in his left eye, which swells and protrudes with the Valsalva maneuver. (A) Photograph of left eye in the sitting position demonstrates a normal left eye. (B) Photograph of left eye after having the patient bend for 10 min shows anterior superior globe displacement with blepharaoptosis of the inferior orbit.

Investigations

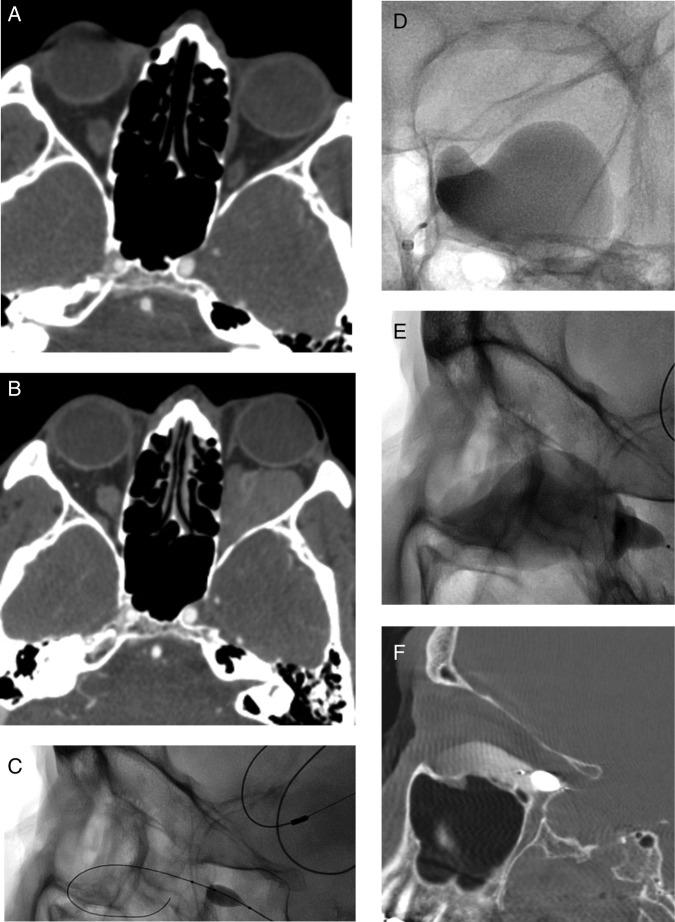

CT and MRI in the prone position and with a Valsalva maneuver confirmed an underlying large saccular left orbital varix with an intimate association of the varix around the inferior rectus muscle and mass effect on the left optic nerve (figure 2A, B).

Figure 2.

(A, B) Axial contrast-enhanced CT images of the orbit demonstrate a small mass within the inferior aspect of the left orbit (A) that enlarges during the Valsalva maneuver (B). (C) Lateral spot fluoroscopic imaging shows a balloon at the origin of the left inferior orbital vein with a wire coiled in the venous varix. (D, E) Anteroposterior (D) and lateral (E) spot fluoroscopic images show a balloon at the origin of the left inferior orbital vein occluding flow into the cavernous sinus with bleomycin mixed with contrast opacifying the venous varix. (F) Sagittal dynaCT shows contrast mixed with bleomycin in the venous varix with a microcatheter balloon at the origin of the inferior ophthalmic vein.

Treatment

Under general anesthesia, the right common femoral artery was punctured in retrograde fashion and a 4 F sheath placed. A 4 F vertebral catheter (Cordis, Miami Lakes, Florida, USA) was advanced into the left internal carotid artery. Internal carotid angiography revealed no arteriovenous filling of the varix. Next, the right common femoral vein was punctured in an antegrade fashion and a 6 F×90 cm Shuttle sheath (Cook, Bloomington, Indiana, USA) was advanced into the left internal jugular vein. The left inferior petrosal sinus was selected with a 4 F×100 cm vertebral catheter (Cordis) and a 0.035 inch angled glidewire (Terumo, Somerset, New Jersey, USA). The Shuttle sheath was advanced over the catheter to the origin of the left inferior petrosal sinus and the catheter exchanged for a 0.044 inch×125 cm DAC catheter (Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA), which was advanced into the left cavernous sinus. Through the DAC catheter, a 4 mm×11 mm Scepter XC dual-lumen balloon catheter (MicroVention, Tustin, California, USA) was advanced over a Synchro 14 microwire (Stryker) and manipulated to select the left inferior ophthalmic vein and the varix (figure 2C). With the balloon inflated at the outflow of the varix, contrast was injected, filling the varix and confirming outflow occlusion. Following this, six units of bleomycin mixed with contrast was injected through the inflated Scepter XC balloon catheter into the left orbital varix and left in place for 10 min (figure 2D, E). During this time, DynaCT (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) of the head was performed and confirmed filling of the 2.4×2.2×3.7 cm left orbital varix (figure 2F). The patient underwent repeat transvenous sclerotherapy approximately 8 weeks later with the same transvenous set-up using 7 units of bleomycin foamed with 25% albumin.

Outcome and follow-up

At 1-month follow-up after the second sclerotherapy he had an excellent response to sclerotherapy with improved visual field testing and no dependent expansion of the varix. At 6-month follow-up there was no evidence of filling of the varix on imaging or clinical examination and his vision improved to 20/25 in the left eye.

Discussion

Orbital venous varices remain challenging vascular lesions for diagnosis and treatment. They generally have a benign course and the number of cases that are symptomatic and require treatment remains small. Surgical treatment can be difficult because of poor surgical margins, especially if the varix extends into the posterior orbit, and complete excision is rarely accomplished. Advances in transcatheter and percutaneous treatments for vascular lesions of the head and neck have enabled treatment of difficult lesions. Embolization for the treatment of an orbital varix was first described by Takechi and colleagues in 1994 using transvenous microcoil embolization.3 Since that time, additional case reports and small case series have been published describing percutaneous coiling, percutaneous n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue embolization, and transvenous coiling.4–8 In recent years there have been a few reports describing the percutaneous injection of bleomycin for treatment of these lesions.9 10 Sclerotherapy has been demonstrated as an effective treatment modality for head and neck venous malformations.

Agents available in the USA that have shown efficacy in the treatment of venous lesions are foamed sodium tetradecyl sulfate, alcohol, and bleomycin. The authors considered the injection of sodium tetradecyl sulfate or alcohol would cause significant swelling and inflammation, conceivably causing an acute compartment syndrome with compression on the optic nerve and loss of vision, so these two agents were not used. In our experience, bleomycin causes less orbital swelling and inflammation. Doxycycline has no role in the treatment of venous lesions. The authors would be cautious about injecting bleomycin without using a balloon as protection since the bleomycin could flow into the cavernous sinus possibly causing cavernous sinus thrombosis. If a balloon catheter cannot be used, the authors would suggest either placing two needles into the lesion so that the material injected can drain through the other needle, or foaming the bleomycin with albumin.

To the best of our knowledge and following a literature review, we believe that transvenous sclerotherapy for the treatment of an orbital varix has not previously been described. Our case demonstrates a curative result with symptomatic and visual improvement following two sessions of transvenous sclerotherapy.

Learning points.

An orbital venous varix is rare and can present with diplopia, proptosis, or hemorrhage.

CT and MRI in the prone position or with a Valsalva maneuver can help confirm the diagnosis of an orbital varix.

Treatment options for an orbital varix include surgery, microcoil embolization, percutaneous n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue embolization, and transvenous or percutaneous sclerotherapy.

Footnotes

Contributors: JJG and VV: writing, editing, and responsible for content. NC and AP: editing. AK: editing, photographs, clinical examination.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gunduz K, Karcioglu ZA. Vascular tumors. In: Karcioglu ZA, ed. Orbital tumors: diagnosis and treatment. 2nd edn New York: Springer, 2015:155–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smoker WR, Gentry LR, Yee NK et al. Vascular lesions of the orbit: more than meets the eye. Radiographics 2008;28:185–204; quiz 325 10.1148/rg.281075040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takechi A, Uozumi T, Kiya K et al. Embolisation of orbital varix. Neuroradiology 1994;36:487–9. 10.1007/BF00593691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai AS, Fong KS, Lim W et al. Bilateral orbital varices: an approach to management. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;24:486–8. 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31818d1f4f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weill A, Cognard C, Castaings L et al. Embolization of an orbital varix after surgical exposure. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:921–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couch SM, Garrity JA, Cameron JD et al. Embolization of orbital varices with N-butyl cyanoacrylate as an aid in surgical excision: results of 4 cases with histopathologic examination. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:614–8. 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokhtarzadeh A, Garrity JA, Cloft HJ. Recurrent orbital varices after surgical excision with and without prior embolization with n-butyl cyanoacrylate. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:447–50. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang CS, Lee S, Yen MT. Optic neuropathy following endovascular coiling of an orbital varix. Orbit 2012;31:418–9. 10.3109/01676830.2012.681098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yue H, Qian J, Elner VM et al. Treatment of orbital vascular malformations with intralesional injection of pingyangmycin. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:739–45. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia R, Xu S, Huang X et al. Pingyangmycin as first-line treatment for low-flow orbital or periorbital venous malformations: evaluation of 33 consecutive patients. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:942–8. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.8229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]