Abstract

Background

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection have shown controversial data concerning the remission hypothesis of IBD due to CD4 count depletion caused by HIV. The aim of our systematic review was to investigate the hypothesis whether low CD4 count due to HIV is related to IBD remission.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed for studies reporting on HIV infection in IBD patients. We extracted characteristics of IBD and HIV disease course and CD4 counts.

Results

Thirteen papers (2 case-control studies, 2 case series, and 9 case reports) were eligible including 47 patients with IBD and HIV infection (43 male; 27 with Crohn’s disease, 19 with ulcerative colitis, and 1 with indeterminate colitis). The IBD diagnosis criteria were heterogeneous among studies. Remission was reported for patients with IBD and HIV infection in 5 studies, including 4 case-control or case series and 1 case report. Four of 5 studies with IBD cases reported remission related to the CD4 count remission hypothesis but only 2 of them explicitly reported the CD4 count cut-off point (500 cells/μL and 200 cells/mm3 respectively). On the contrary, 7 case reports described an active IBD course or relapse even in patients under immunosuppression.

Conclusions

Current literature cannot support or reject the CD4 count remission hypothesis in IBD patients with HIV infection. Prospective studies using uniform criteria on IBD and HIV disease course and CD4 counts are needed.

Keywords: HIV, IBD, CD4, remission, systematic review

Introduction

Inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is currently believed to be initiated and perpetuated by an aggressive cell-mediated immune response to an unknown environmental antigen in a genetically susceptible host. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are sharing common pathways, despite the fact that CD is a T-cell-mediated disease while UC is characterized as an antibody-mediated disease. Acute episodes of both CD and UC are characterized by infiltration of large numbers of inflammatory cells including monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes into the intestinal epithelium and wall. This inflammatory infiltrate is accompanied by extensive mucosal and transmural injury, including edema, loss of goblet cells, decreased mucus production, abscesses, erosions, and ulcerations. Pathology specimens suggest an important role for leukocytes in the pathophysiology of IBD. Likewise, CD4+ T-lymphocytes seem to play an important role. HIV infection results in a wide range of clinical consequences from an asymptomatic stage to life-threatening opportunistic diseases [1]. The immunological changes associated with infection by HIV include a progressive loss of peripheral and mucosal CD4 lymphocyte number and function, which leads to the development of opportunistic infections. There is also a switch from cell-mediated Th1 response to that of an antigen-antibody-mediated Th2 response [2].

A potential pathophysiological relationship between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and IBD remains controversial. There are some case series [1-4] and a few case reports [5-13] of IBD in individuals infected with HIV. Some studies suggested that the incidence of IBD in individuals with HIV is increased, either because of the rectal inflammation, or because the changes in the immune system induced by HIV such as loss of CD4 lymphocyte number and function facilitate the development of IBD [2]. Clinical studies hypothesized that a progressive decline in CD4 count caused by HIV may reduce IBD disease activity and contribute to remission [1-4,11,13]. Other investigators claimed that IBD and HIV run an independent course [5-10,12].

In our paper, we systematically tried to retrieve all the studies that included at least one group of patients with IBD and HIV infection and investigate whether they supported that IBD and HIV infection are presented with an independent course in these patients, or whether they provided clinical data that CD4 count remission hypothesis may exist.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We searched PubMed (from inception to September 2013) using combinations of search terms including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Electronic searches were supplemented by perusal of the references of the retrieved papers.

Study selection

We included studies irrespective of study design that recruited at least one group of adults or adolescents presenting with both IBD and HIV infection regardless of which diagnosis preceded. We also included studies including patients with a simultaneous diagnosis of IBD and HIV infection. However, we excluded studies in which IBD was reported as an HIV-related opportunistic infection, and studies without primary data, i.e., commentaries, or letters to the Editor. We included only papers in English.

Data extraction

For each study, we extracted the name of first author, publication year, country, and type of research center or department where the study was conducted. We also recorded sample size, age of participants, gender, preceding diagnosis (IBD or HIV), and time interval between the two diagnoses. We further extracted the type of IBD (CD, UC, or indeterminate colitis [IC]), and what criteria for IBD diagnosis were mentioned, i.e., clinical, laboratory, radiological, endoscopic, and histological. In addition, we recorded whether IBD distribution, IBD treatment, and IBD complications or specific outcome were reported, whether a specific diagnostic score was used to support IBD relapse, and whether surgery or hospitalization were required during relapse. For HIV infection, we captured whether HIV risk factors that may have induced HIV infection were mentioned, and the potential mode of HIV transmission when data were available; the CD4 count at different times, if reported; and whether HIV treatment, and complications or specific outcome were mentioned. We also recorded any cause for hospitalization or death.

Finally, we noted whether the authors reported any hypothesis related to IBD and HIV infection course. Specifically, we recorded whether IBD remission was mentioned, whether the authors referred to the CD4 count-related IBD remission hypothesis to support patients’ remission, and, if they did, whether they provided a CD4 cut-off level related to IBD remission.

All items were extracted by one investigator (AS) and were confirmed by two other investigators (AT and KHK). Discrepancies were resolved after consensus.

Results

Eligible studies

The search of PubMed yielded 604 citations. After screening titles and abstracts, 566 citations were rejected because they were irrelevant to our research questions. We retrieved in full text 38 articles. We rejected 9 of 38 papers because they were not written in English (3 were written in Spanish, 3 in German, 2 in French, and 1 in Japanese). We further excluded 12 articles because after reading the full text we concluded that they were irrelevant to our research question; and 4 articles because they did not include primary data. Thus, we finally selected 13 papers. The 13 articles included 2 case-control studies, 2 case series, and 9 case reports.

Characteristics of eligible studies

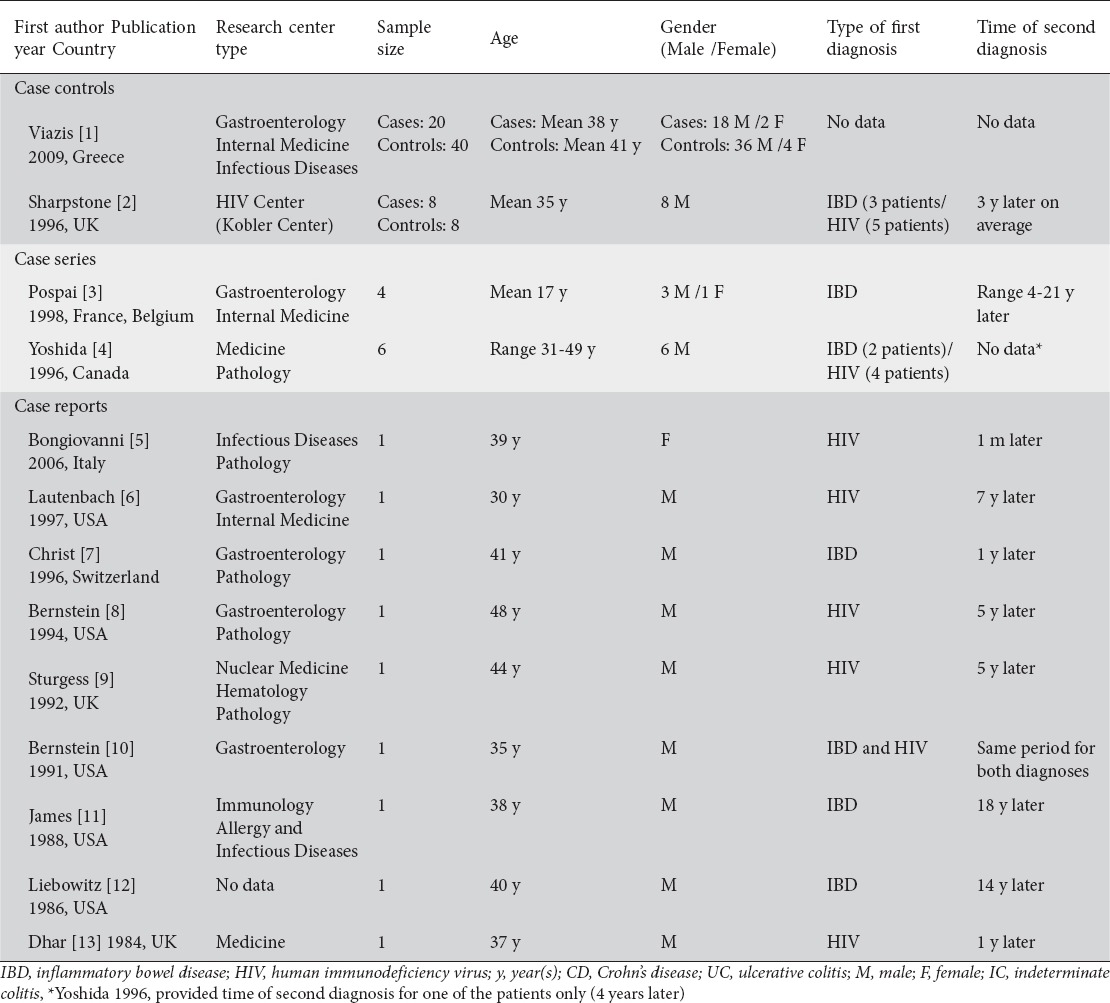

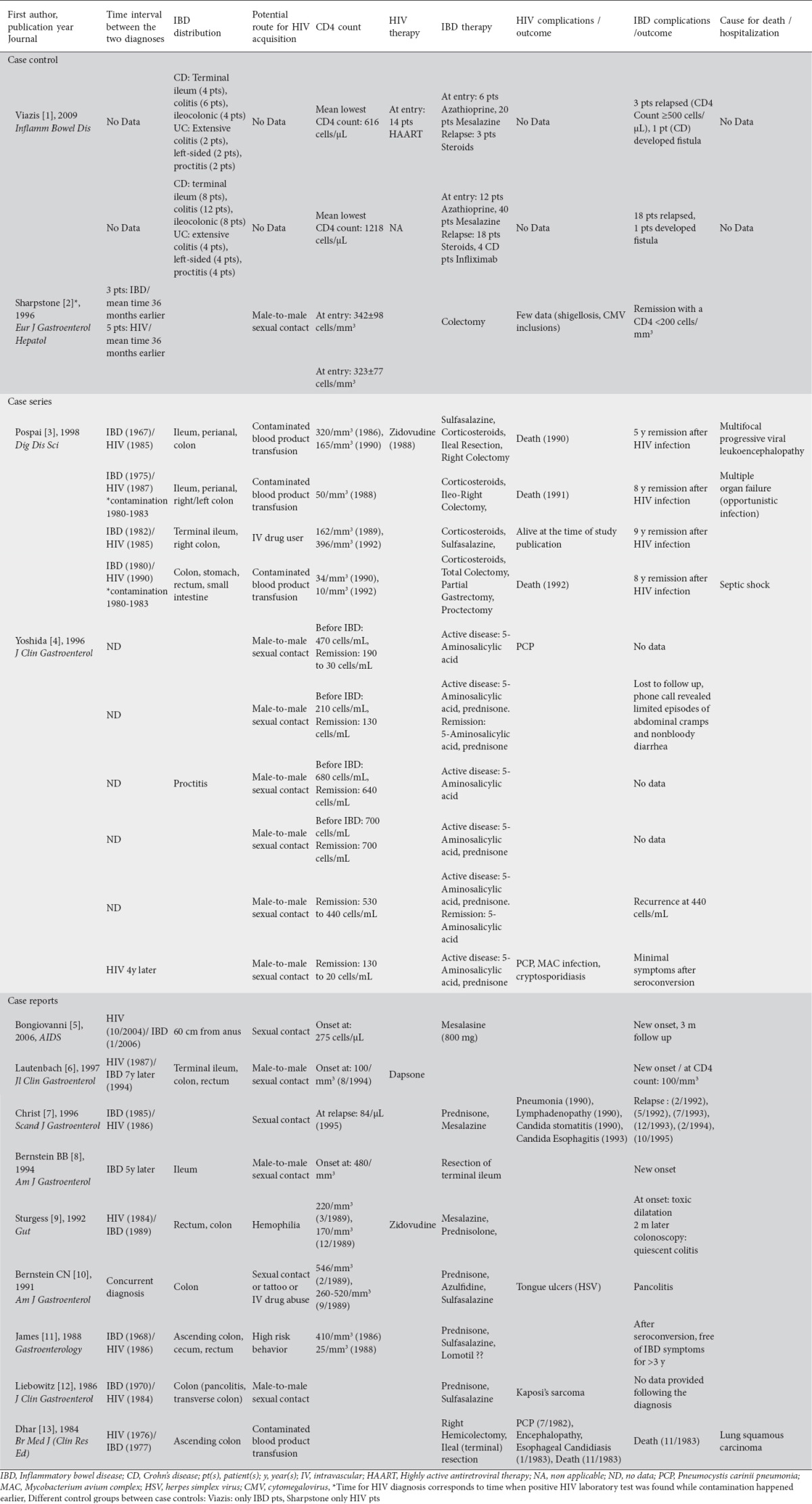

Studies were published between 1984 and 2009. Five articles were conducted in USA, 1 in Canada, and 7 in Europe. Case series studies included a small number of participants ranging from 4 to 8. There were two case-control studies that included 60 and 16 patients respectively. In total, there were 47 patients with IBD and HIV, one group of 40 patients with only IBD, and one group of 8 patients with only HIV. The majority of participants were males, 17-49 years old. Of the 47 patients with IBD and HIV, IBD predated HIV infection in 12 of them, 14 were HIV positive at the time IBD occurred, while one case report included a patient with concurrent diagnosis of IBD and HIV. For 20 patients, there was no information on which disease was diagnosed first (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in eligible studies

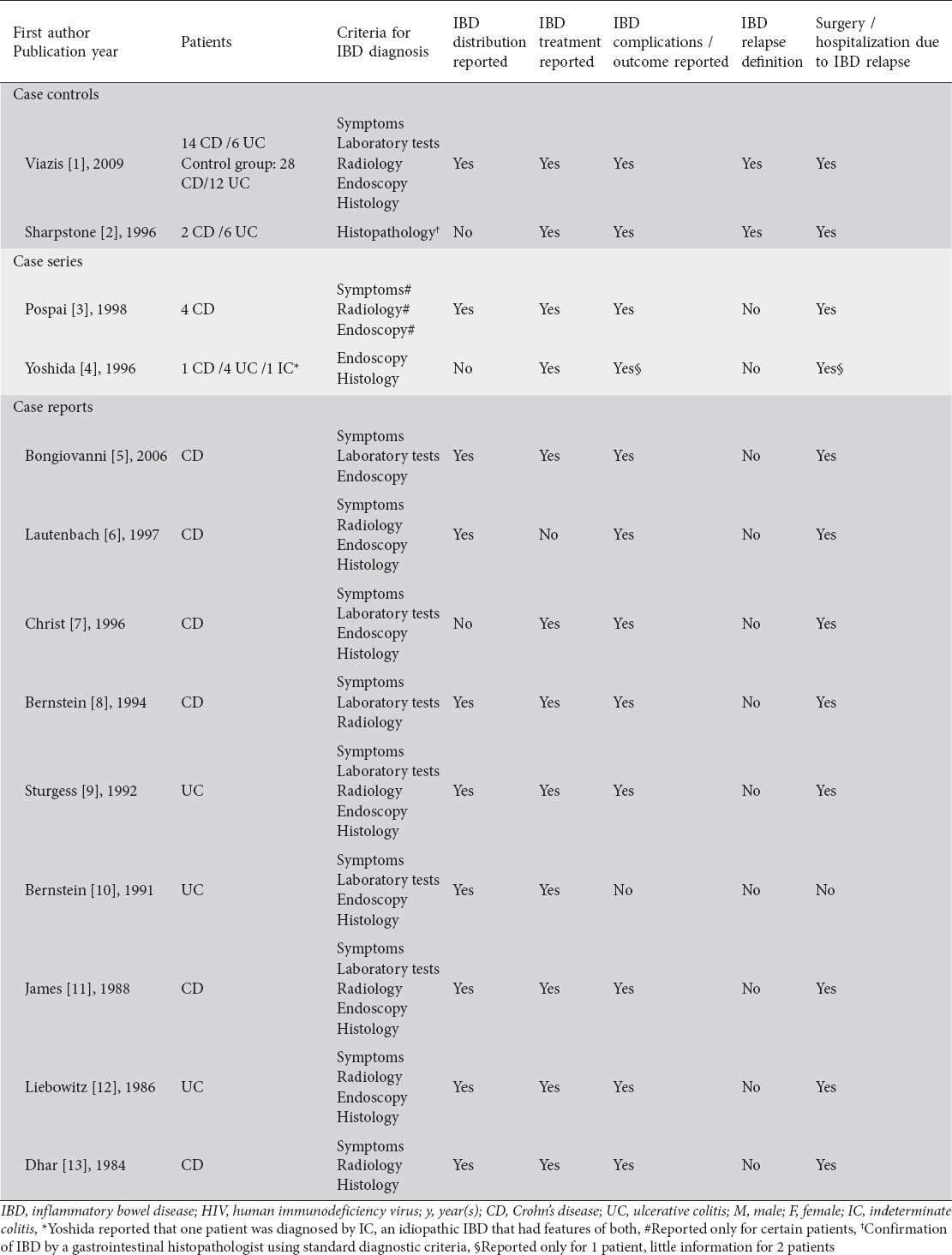

IBD type, criteria of diagnosis, distribution, therapy, complications, and outcome were generally reported among the studies. However, IBD diagnosis criteria were heterogeneous among the studies. Two studies clearly stated that they used a definition to assess relapse for IBD. Viazis et al defined IBD relapse as necessity for surgery or clinical recurrence, as assessed by an experienced clinician based on clinical features of diarrhea, abdominal pain, general well-being, weight loss, and inflammatory parameters hemoglobin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, white cell count, and platelets. The definition of IBD relapse described by Sharpstone et al included more than three bowel movements a day for more than 3 days in the absence of small bowel pathogens. Most of the studies also reported the need of hospitalization, or surgery when applicable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of IBD and IBD course of patients in eligible studies

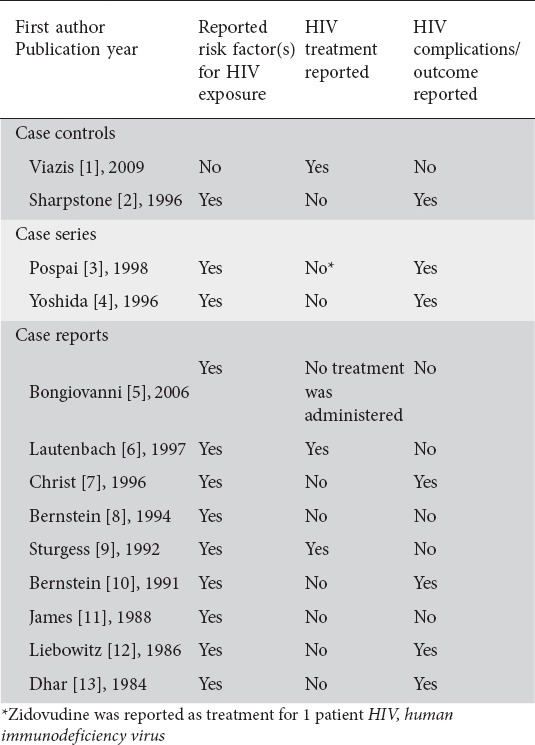

Almost all studies reported risk factor(s) for HIV exposure. However, only two studies described treatment for HIV. Half of the studies reported complications or outcomes for HIV infection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of HIV infection and HIV infection course of patients in eligible studies

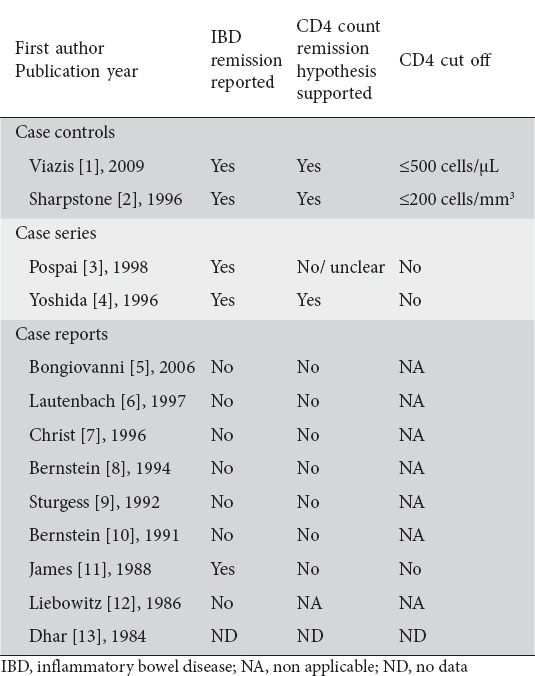

CD4 count-related IBD remission hypothesis

Remission was described for patients with IBD and HIV infection in 5 studies, including case-control studies [1,2], case series [3,4], and one case report. Seven of the 9 case reports reported no remission for the patients while one case report provided no data on remission. Four of the five studies with cases presenting with remission referred to the CD4 count-related IBD remission hypothesis. However, only two of them mentioned a CD4 count cut-off point in relation to CD4 count remission hypothesis (Table 4).

Table 4.

CD4 count IBD remission hypothesis for patients in eligible studies

Viazis et al [1] compared IBD activity in 20 IBD patients infected with HIV with a matched group (2 controls per case) of 40 IBD patients without HIV. The relapse rate of IBD was significantly lower for IBD patients with HIV infection (0.016/year vs. 0.053/year; P=0.032). However, these IBD relapse rates were relatively low in these patients as compared to other studies [1]. In the same study, survival curves showed that time to first relapse is longer for IBD patients infected with HIV [1]. Pospai et al [3] reported 4 cases of patients with long-standing relapsing CD who became infected with HIV and experienced a stable remission for the next 5, 8, 8, and 8 years respectively, a period that corticosteroid therapy was stopped. However, explicit data on immunosuppression were inadequately provided during CD remission, except for the latest period when the patients presented both with CD and HIV infection. Yoshida et al [4] reported that 3 patients with UC experienced active UC, with mildly depressed CD4 counts. One patient with CD had an episode with a CD4 count equal to 210 cells/mL. The rest 2 patients, who were followed until the CD4 count reached an end-stage nadir, experienced quiescence in IBD activity. Sharpstone et al [2] studied 8 cases with IBD-HIV coinfection. All IBD exacerbations occurred in patients with a CD4 count more than 200 cells/mm3. Finally, James et al [11] reported a patient with an 18-year history of CD who became infected with HIV and had a complete remission of IBD with progressive immunodeficiency. However, the patient had been asymptomatic for 2 years before the diagnosis of HIV infection, and his initial CD4 count was 410/mm3, a level not commonly associated with severe immune suppression and risk for opportunistic disease.

Dhar et al described a man with classic HIV-related illnesses (PCP, monilial esophagitis) and inactive CD. However, HIV serological testing had not been developed when the patient was presented with the symptoms, and the authors were not able to clarify which disease occurred first [12].

On the contrary, 7 of the 9 case reports argued against the CD4 count-related IBD remission hypothesis [5-10,12]. They described an active IBD or IBD relapse even when patients were in severe immunosuppression. Four case reports [5-7,9] described IBD as a new onset (event) in an HIV-infected patient. One of these presented a HIV-positive patient with a CD4 count equal to 170 cells/mm3 at the de novo development of UC [9]. However, this patient was not followed long enough so that the authors could report disease activity with a CD4 count <170 cells/mm3. One case report did not clearly state the CD4 cell count because it had been published before the absolute CD4 count became a standard clinical point of reference (Table 5) [12].

Table 5.

Analytical overview of studies, case series and case reports on HIV and IBD

Discussion

There were few studies, mainly case reports, on a very small number of patients with IBD and HIV infection. The largest case-control study suggested that relapse in IBD patients infected with HIV had less frequent relapses than IBD patients without HIV [1]. The small number of case series studies tended to support that CD4 depletion may be related with IBD remission [1-4]. However, the absence of a control group substantially compromises the robustness of their conclusion. Most case reports supported that IBD remission did not follow HIV infection in their patients [5-10,12]. However, in addition to their weakness for firm conclusions due to study design, there were issues related to the CD4 count, which either was not clearly reported or remained at higher levels than the CD4 count in studies that supported the IBD-HIV remission hypotheses.

Small sample sizes may be unavoidable since the reported prevalence of HIV among IBD patients is generally low. Specifically, Viazis et al [1], claimed that a 21-year (1988-2009) IBD database review of more than 1,600 patients revealed 20 patients with IBD and coexisting HIV. Sharpstone et al [2] reported a 41/100,000 mean incidence in the 6-year study period, but noticed that the prevalence of IBD in the region’s HIV population in 1993 was 364/100,000. Yoshida et al [4] described that during a 4-year period (1989-1993) in a 2-million population area according to hospital discharges, there were 1,839 patients with HIV diagnosis, and 1,115 patients with IBD diagnosis, but only 6 patients with both diagnoses. To address this issue, an international registry of IBD patients with HIV infection might help increase the number of patients to be prospectively followed long term and improve the precision of conclusions.

Diagnosis of IBD in HIV positive patients is often difficult. Patients with HIV frequently present with diarrhea caused by opportunistic infection, and may be misdiagnosed as having chronic inflammatory bowel disease. In fact, some of these infections may mimic IBD, e.g., cytomegalovirus (CMV), Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, Treponema pallidum, and other pathogens including Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, Isospora belli, Giardia lamblia, herpes simplex virus, Entamoeba histolytica, and several other bacteria [3,7]. In the case reported by Wajsman et al [15] the pathogen (CMV) was identified only by microscopic examination of the bowel resected during a second laparotomy. The terminal ileum had profound mucosal ulcerations and transmural fibrosis without granuloma, an endoscopic presentation similar to the case described by Bernstein et al [3] Gastrointestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma, with extensive submucosal infiltration and overlying mucosal inflammation, may also resemble UC [4]. Thus, it is substantial that diagnosis of IBD in HIV patients is confirmed by biopsy in all cases.

Absolute CD4 cell count might not be the appropriate factor to correlate with IBD course. CD was suggested that may depend more on CD4 functional ability and less on their absolute number [6]. Specifically, although no difference in absolute numbers of lamina propria CD4 cells was noted when comparing patients with CD with healthy controls, a higher proportion of lamina propria T lymphocytes secreting IL-2 (indicating T-cell activation) was observed in patients with CD compared with controls [15,16]. Additionally, peripheral T-cell counts may not accurately reflect levels at the intestinal mucosa [8], and thus a decrease in the peripheral blood CD4 count does not necessarily imply intestinal mucosal immune cell depletion. However, in patients with CD, this issue remains controversial [6].

Our review had several limitations. The type of the study design and the sample size for the eligible studies did not allow us for any robust conclusion. In addition, specific issues related to both IBD and HIV characteristics were also raised. The definition of diagnosis and relapse of IBD was heterogeneous among the studies. Despite the fact that all studies reported diagnostic criteria, the use of biopsy was not uniquely applied. Moreover, relapse definition was mentioned only in two of the studies. The CD4 count has significant diurnal variation and day-to-day fluctuations, and, therefore, investigators who design studies on patients with IBD and HIV should agree on whether the lowest CD4 count or the mean CD4 count would be more appropriate. Otherwise, the diversity of CD4 count reporting would pose an additional barrier in the interpretation of the results. Finally, eligible studies did not provide information to explore other speculations, i.e. individuals who develop IBD involving the rectum before their HIV status is known may have an increased risk of HIV transmission during unprotected anal intercourse.

In conclusion, there is a paucity of data in the literature to support or reject the hypothesis that CD4 count depletion may induce remission of bowel inflammation in IBD patients. However, if we had to pick a side on that argument, there is a trend supporting the CD4 hypothesis and most reports seem to suggest that IBD might be less aggressive in patients infected with HIV.

Due to the low prevalence of patients with IBD and HIV infection, an international registry is recommended to prospectively follow larger number of patients. In addition, certain requirements, including the performance of biopsy for IBD exacerbation diagnosis, and appropriate CD4 count reporting should be ensured to enhance robustness of conclusions.

Biography

Ioannina Medical School, Greece

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Viazis N, Vlachogiannakos J, Georgiou O, et al. Course of inflammatory bowel disease in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:507–511. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharpstone D, Duggal A, Gazzaed B. Inflammatory bowel disease in individuals seropositive for the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:575–578. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pospai D, Rene’ E, Fiasse R, et al. Crohn’s disease stable remission after human immunodeficiency virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:412–419. doi: 10.1023/a:1018883112012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida E, Chan N, Herrick R, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection, the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:24–28. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bongiovanni M, Ranieri R, Ferrero S, et al. Crohn’s disease onset in an HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infected woman taking pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin. AIDS. 2006;20:1989–1990. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247127.19882.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautenbach E, Lichtenstein GR. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and Crohn’s disease: the role of the CD4 cell in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:456–459. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199709000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christ AD, Sieber CC, Cathomas G, et al. Concomitant active Crohn’s disease and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:733–735. doi: 10.3109/00365529609009158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein BB, Gelb A, Tabanda-Lichauco R. Crohn’s ileitis in a patient with longstanding HIV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:937–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sturgess I, Greenfield SM, Teare J, O’Doherty MJ. Ulcerative colitis developing after amoebic dysentery in a haemophiliac patient with AIDS. Gut. 1992;33:408–410. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.3.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein CN, Snape WJ. Active idiopathic ulcerative colitis in a patient with ongoing HIV-related immunodepression. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:907–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James S. Remission of Crohn’s disease after human immunodef iciency virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1667–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebowitz D, McShane D. Nonspecific chronic inflammatory bowel disease and AIDS. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:66–68. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198602000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhar JM, Pidgeon ND, Burton AL. AIDS in a patient with Crohn’s disease. BMJ. 1984;288:1802–1803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6433.1802-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabs DA. Improving the reporting of clinical case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wajsman R, Cappell MS, Biempica L, Cho KC. Terminal ileitis associated with cytomegalovirus and the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:790–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selby WS, Janossy G, Bofill M, Jewell DP. Intestinal lymphocyte subpopulations in inflammatory bowel disease: an analysis by immunohistological and cell isolation techniques. Gut. 1984;25:32–40. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]