Abstract

Background

Weight concerns are widely documented as one of the major barriers for girls and young adult women to quit smoking. Therefore, it is important to investigate whether smokers who have weight concerns respond to tobacco control policies differently than smokers who do not in terms of quit attempts, and how this difference varies by gender and country.

Objective

This study aims to investigate, by gender and country, whether smokers who believe that smoking helps control weight are less responsive to tobacco control policies with regards to quit attempts than those who do not.

Methods

We use longitudinal data from the International Tobacco Control Policy (ITC) Evaluation Project in the US, Canada, the UK, and Australia to conduct the analysis. We first constructed a dichotomous indicator for smokers who have the weight control belief and then the disparity in policy responsiveness in terms of quit attempts by directly estimating the interaction terms of policies and the weight control belief indicator using generalized estimating equations.

Findings

We find that weight control belief significantly attenuates the policy impact of tobacco control measures on quit attempts among US female smokers and among UK smokers. This pattern was not found among smokers in Canada and Australia.

Conclusions

Although our results vary by gender and country, the findings suggest that weight concerns do alter policy responsiveness in quit attempts in certain populations. Policy makers should take this into account and alleviate weight concerns to enhance the effectiveness of existing tobacco control policies on promoting quitting smoking.

Introduction

Weight-related concerns such as weight gain after quitting have been shown to discourage quitting and quit attempts among smokers.[1–5] Nevertheless, the health benefits of quitting remain substantial even after taking account of the adverse health impact of the post-cessation weight gain.[6] In addition, for those smokers who use smoking as a weight control method, it may not be an efficient tool to control weight.[7] Existing studies indicate that heavy smokers, compared with light smokers, tend to be heavier, and ever-smokers, compared with never-smokers, do not experience less weight gain over time.[8] Moreover, smoking is found to be associated with less physical activity and unhealthy diets that may in fact contribute to a weight gain.[9–11] Despite lack of scientific evidence that smoking is an effective weight control method, it is often regarded as a means of losing weight. Using US data, Cawley et al. (2004, 2006) found that weight gain is significantly associated with smoking initiation among girls, [12,13] and 46% of girls and 30% of boys who are currently smoking, use cigarettes to control weight. [14]

While it is important to inform the public that smoking as a weight control method is indeed ineffective [16–21], little is known about whether weight concerns may attenuate the effectiveness of tobacco control policies in reducing smoking, that is, whether it results in an insignificant or reduced impact among population groups who have these concerns. Some indirect evidence suggests that they do; a high prevalence of weight concerns and low responsiveness to tobacco control policies often are observed together in certain populations [22–28]. Studies using US data show that while weight concerns are higher among females than among males [1–3, 5, 14, 15, 29], the price impact on smoking is either insignificant or lower for females than for males.[23, 25–27] US girls have also been found unresponsive to rising cigarette prices and are more likely to initiate smoking once experiencing a weight gain.[12] Similar patterns are also found in racial comparisons. Compared with minority groups such as African Americans, Caucasians in the US are more likely to report using cigarettes for weight control and are less price-responsive. [14, 22–25, 29] In addition to the above evidence, Shang et al. (2013) investigated the impact of the belief that smoking helps control weight on smokers’ price responsiveness to reduce cigarette consumption and found that female smokers in the US who hold such a belief are less price-responsive than those who do not. [15]

In sum, very little evidence exists for the role of weight concerns in people’s response to tobacco control policies. Although studies indicate that weight concerns inhibit quit attempts, it remains unclear whether weight concerns lower quit attempts through lowering smokers’ response to tobacco control policies such as increasing cigarette prices. Therefore, it is important to extend the research to examine such mechanisms and elucidate whether policies that address weight concerns are needed to improve the effectiveness of other tobacco control policies. In this study, we employ the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project data from the US, the UK, Canada, and Australia (ITC-4 country) to investigate the interaction effect of weight control belief and a variety of tobacco control policies (cigarette prices, anti-smoking messaging, work-site smoking bans, bar/pub smoking bans, and restaurant smoking bans) on quit attempts. Based on the existing literature that show women are more likely to have weight concerns [1–3, 5, 12–15, 29], all analyses are conducted by gender.

Methods

Data

The International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC Project) conducts parallel longitudinal surveys of smokers and other tobacco users across 22 countries. The ITC surveys are designed to evaluate the policies of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Fong, et al. 2006) and their longitudinal properties allow us to follow smokers over years while observing their quitting and quit attempt behavior since the initial wave. [30] Compared with cross-sectional data, in the longitudinal data quit attempts are observed and less likely to contain measurement errors, and, when studying how tobacco control policies or cigarette prices are associated with quit attempts, longitudinal data allow a more precise match of locations where the policies are implemented to the smokers who are exposed to these policies.

We utilize ITC-4 Country data (US, UK, Canada, and Australia) waves 1–5 (2002–2007) that contain responses from smokers on their level of agreement with the statement that smoking helps control weight. The ITC project also contains rich information on tobacco-use related factors including cigarette prices, exposure to tobacco control policies, and individual-level demographic characteristics that allow for testing the policy responsiveness by weight control belief while controlling for other factors.

In order to identify weight concerns related to smoking, we exploit a question that measures smokers’ level of agreement with the following statement using a 5-point scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree):

“Smoking helps weight control.”

The answers are employed to construct a dichotomous measure of the belief by coding those who answered strongly agree or agree with 1 and the rest with 0. This indicator explicitly shows if a smoker may use smoking as a potential means to control weight, regardless of his or her actual body weight or body image. [12,31] We consider this indicator to be a rudimentary measure of smoking related weight concerns.

Table 1 contains the description and definition of weight control belief indicator, policy measures, and other correlates that are estimated in our analyses. The baseline period to start tracking quit attempt behavior is the first wave of the survey when all participants were smoking. Thus the analyzed sample consists of the second and later waves of each country. Smokers who have made a quit attempt since the last survey were assigned a value of 1 and smokers who have not were assigned a value of 0. This quit attempt indicator is also equivalent to the percentage of smokers who quit or ever tried to quit since the last survey. The individual characteristic confounders that are controlled include respondents’ age in the survey year (in both linear and quadratic forms), marital status, employment status, education (indicators for three categories: low, middle, and high education levels), and income (indicators for three categories: low, middle, high income levels). Respondents with missing education, income or employment status were dropped from the sample.

Table 1.

Variable Description and Definition

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Individual Level | |

| Quit attempts | A dichotomous indicator equals one is the respondent has attempted to quit since the last wave, 0 otherwise |

| Weight control belief =1 | A dichotomous indicator equals one is the respondent strongly agrees or agrees on the weight control effect of smoking in the last wave, 0 otherwise |

| Age | Age at the survey year |

| Married | A dichotomous indicator equals one is the respondent is married, 0 otherwise |

| Employed | A dichotomous indicator equals one is the respondent is employed, 0 otherwise |

| Education | Binary indicators for 3 categories: low, middle and high education (For the US, Canada and Australia, these categories refer to high school or less, community college/technical school or some college, and college and above; For the UK, these categories refer to secondary school, some college, and college or above.) |

| Income | Binary indicators for 3 categories: low, middle and high income (For the US, Canada and Australia, these categories refer to annual household income less than $30,000, $30,000–59,999, and $60,000 or above; For the UK, these categories refer to annual household income at £15,000 or lower, £15,001–30,000, and £30,001 or higher.) |

| Stratum Level | |

| Price | Stratum specific cigarette prices for a pack of 20 cigarettes in constant 2010 dollars, constructed using the median price reported in each stratum. |

| Worksite bans | The stratum level average of individuals’ exposure to smoking restrictions at work place (1 no restriction, 2 some restriction, 3 full restriction); Possible range: 1–3. |

| Bar bans | The stratum level average of individuals’ exposure to smoking restrictions at bars (1 no restriction, 2 some restriction, 3 full restriction); Possible range: 1–3. |

| Restaurant bans | The stratum level average of individuals’ exposure to smoking restrictions at restaurants (1 no restriction, 2 some restriction, 3 full restriction); Possible range: 1–3. |

| Anti-smoking messaging | Out of a number of anti-smoking broadcasting venues (TV, radio, etc.), the fraction that each respondent was exposed to was calculated. These individual fractions were averaged to the stratum level and rescaled by multiplying by 10. Possible range: 1–10. |

The ITC surveys asked respondents to report their recent exposure to tobacco control policies. The last purchase information of cigarettes such as the unit of cigarettes and the price per unit (per stick, pack, or carton) was also asked. These self-reported measures of tobacco prices and control policies are crucial determinants of smoking behaviors yet highly correlated with individual unobserved heterogeneity in such behaviors. For example, heavy smokers are more likely to purchase cheaper cigarettes and thereafter report lower cigarette prices. They may be more likely to notice tobacco advertisements and report more such exposure as well. As a result, instead of directly using these self-reported measures in our analyses, we aggregated them at the stratum level where strata correspond to regions in each of the countries. We analyzed these stratum average measures, which are more likely to reflect market prices and, as a result, less likely to be endogenous. Thus, to obtain stratum cigarette prices, we first calculated individuals’ self-reported cigarette prices for a pack of 20 cigarettes and constructed the stratum aggregated cigarette prices as the median value of prices that were reported by those who live in the stratum. We used aggregated median prices instead of mean prices because they are more robust to extreme values [32]. These prices were then converted into 2010 constant international dollars using Purchasing-Power Parity (PPP) and Consumer Price Index (CPI) of the country. PPP conversion factor and CPI of each country were obtained from the International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook database.

Likewise, individuals’ exposures to worksite smoking bans, anti-smoking messaging, smoking restriction in bars, and smoking restriction in restaurants were calculated and aggregated to stratum-level mean index measures (details are presented in Table 1). Specifically, in ITC surveys, respondents were asked to report their recent exposure to anti-smoking messaging in a list of venues (TV, radio, posters, etc.). To develop an anti-smoking index, we first estimated, for each respondent, the fraction of venues at which the respondent has been exposed to, then aggregated these individual-level indices to the stratum level using mean indices, and rescaled the indices by multiplying them by 10 (the index ranges 1–10). The worksite, bar, and restaurant indices were constructed at the stratum level using the mean of reported policy restriction levels in these locations (1 no restriction, 2 some restriction, 3 full restriction, indices range 1–3).

Models

In light of previous studies where significant gender disparity in weight concerns was found, and since tobacco control policies differ by countries [17], it is likely that the responses to tobacco control policies are manifested differently by gender and country. Hence, we stratified our analyses by gender and country in addition to carrying out analyses by pooling both genders. We restricted our studied sample to adult smokers aged 18–75. Our sample consists of smokers who smoked in the last wave and our dependent variable, the quit attempt indicator, measures both smokers who actually quit since the last wave and smokers who attempted to quit but failed. In addition, given the high co-linearity between stratum-level tobacco control policies and wave fixed effects, we analyzed each policy separately while controlling for other policies using a single mean measure constructed using the mean of all other policy indices (Appendix Table 1).

Logistic regressions are used to directly test whether policy impacts vary by the weight control belief indicator for each tobacco control policy, respectively:

| (1) |

where Quit_Attemptit denotes the indicator of ever making a quit attempt since the last survey for person i at wave t. Policykt denotes one of the studied stratum-specific policies which are cigarette price, work-site smoking bans, bar smoking bans, restaurant smoking bans, and anti-smoking messaging. Other_Policy_Controlkt denotes the constructed single mean measure of all tobacco policies other than the Policykt. I(Belief = 1)it − 1 denotes the dichotomous measure of the weight control belief in the last survey. Following Cawley et al. (2004) [12], we use one lag of the belief indicator instead of the current one to reduce the potential reverse causality between quit attempts and weight control belief. This is because smokers who quit or attempted to quit may experience a post-cessation weight gain and are more likely to agree that smoking helps weight control. Our main variable of interest is the interaction terms of the policy variables and the weight-control belief indicator. A Wald test of the estimate of the interaction term provides a direct test of whether policy responsiveness differs by the weight control belief. Xit is a vector of individual demographic characteristics including education (low education as the omitted category, middle, and high education), income (low, middle, with high income as the omitted category), marital status, employment, age, a quadratic form of age, and wave fixed effects. In the regressions using pooled samples of both genders, an indicator of being male is added to the model.

Given that the surveys for each country are longitudinal, to account for the correlation of the same individual over time, we use weighted generalized estimating equations (GEE) to estimate Equation (1). Logistic link, a binomial family, and exchangeable working correlation are applied in estimating the method [33]. GEE extends generalized linear models by adjusting for the correlated data, and yields consistent estimates even when the covariate structure is mis-specified.[34] Additionally, the corresponding standard errors are estimated using logistic regressions after accounting for the complicated survey designs of each ITC country. All analyses were conducted using Stata SE version 13.1.

Results

We report weighted descriptive summary statistics of the quit attempt indicator and covariates by country and gender in Table 2. These summary statistics are also adjusted for correlations between the same individuals over years. The results show that in the studied countries, quit attempt rates are 37–42% among male smokers and 39–42% among female smokers. Consistent with the previous literature using the US data, we find that the prevalence of weight control belief among female smokers is about 10 percentage points higher than among male smokers. Namely, in the US and Canada, weight-control-belief prevalence is 23% among male smokers and 38–39% among female smokers; in the UK, it is 28% among male and 39% among female smokers; in Australia, it is 25% among male and 32% among female smokers. The mean age of these smokers is about 42–43 years. In addition, the stratum-level policy variables are similar between genders within a country.

Table 2.

Weighted Summary Statistics for Smokers Aged 18–75, by Gender

| U.S. | Canada | U.K. | Australia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Quit Attempts | 0.37 (0.02) | 0.41 (0.01) | 0.42 (0.01) | 0.42 (0.01) | 0.37 (0.01) | 0.39 (0.01) | 0.40 (0.01) | 0.42 (0.01) |

| Weight Control Belief = 1 | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.38† (0.01) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.39† (0.01) | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.39† (0.01) | 0.25 (0.01) | 0.32† (0.01) |

| Age | 42.35 (0.46) | 43.19 (0.40) | 42.33 (0.44) | 43.06 (0.40) | 43.11 (0.49) | 43.27 (0.51) | 41.62 (0.46) | 40.96 (0.40) |

| Married | 0.33 (0.02) | 0.33 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.01) | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.31 (0.01) | 0.27† (0.01) | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.01) |

| Employed | 0.74 (0.01) | 0.62† (0.01) | 0.78 (0.01) | 0.67† (0.01) | 0.78 (0.01) | 0.62† (0.01) | 0.77 (0.01) | 0.61† (0.01) |

| Education | ||||||||

| low | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.01) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.36† (0.02) | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.40 (0.01) |

| Middle | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.33 (0.01) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.30 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) |

| High | 0.60 (0.02) | 0.58 (0.02) | 0.55 (0.02) | 0.56 (0.01) | 0.42 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.02) | 0.38 (0.02) | 0.35 (0.01) |

| Income | ||||||||

| Low | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.42† (0.01) | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.34† (0.01) | 0.21 (0.01) | 0.37† (0.02) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.32† (0.01) |

| Middle | 0.39 (0.02) | 0.38 (0.01) | 0.40 (0.02) | 0.37 (0.01) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.37 (0.02) | 0.36 (0.01) | 0.35 (0.01) |

| High | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.21† (0.01) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.30† (0.01) | 0.43 (0.02) | 0.26† (0.01) | 0.42 (0.02) | 0.33† (0.01) |

| Stratum Level Policy | ||||||||

| Price | 3.68 (0.03) | 3.64 (0.02) | 6.04 (0.03) | 6.01 (0.02) | 7.36 (0.01) | 7.36 (0.01) | 6.02 (0.01) | 6.01 (0.01) |

| Worksite bans | 2.49 (0.01) | 2.47† (0.00) | 2.49 (0.01) | 2.50 (0.00) | 2.28 (0.00) | 2.28 (0.00) | 2.51 (0.00) | 2.53 (0.00) |

| Bar bans | 2.04 (0.01) | 1.99† (0.01) | 2.29 (0.01) | 2.30 (0.01) | 1.73 (0.00) | 1.72 (0.00) | 2.09 (0.00) | 2.10 (0.00) |

| Restaurant bans | 2.43 (0.01) | 2.39† (0.01) | 2.55 (0.01) | 2.56 (0.01) | 2.12 (0.00) | 2.11 (0.00) | 2.68 (0.00) | 2.69 (0.00) |

| Anti-smoking Messaging | 4.19 (0.01) | 4.19 (0.01) | 4.57† (0.01) | 4.59 (0.01) | 4.30 (0.01) | 4.29 (0.01) | 4.72 (0.01) | 4.74† (0.01) |

| N | 1786 | 2480 | 2216 | 2844 | 2194 | 2805 | 2453 | 2998 |

Note:

denotes that gender means are significantly different at 5%. Standard errors are in parentheses.

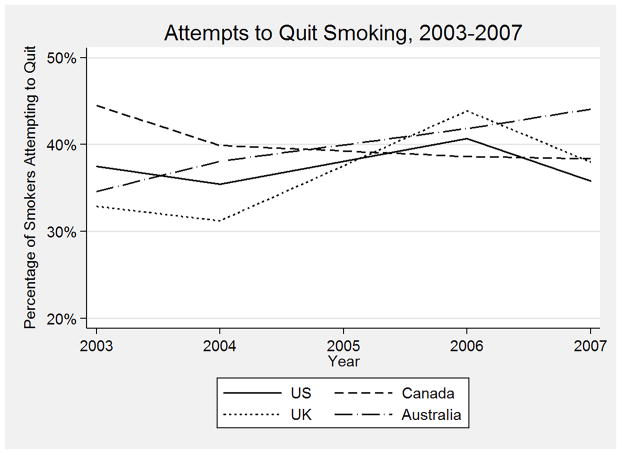

Further, in Figure 1, we plot the attempt rates over years for each country and show that the quit-attempt rates in the 4 countries are about 30–45%.

Figure 1.

Quit Attempts in the USA, the UK, Canada, and Australia

Tables 3 shows the results from estimating equation (1). The estimates indicate that among US female smokers, weight control belief significantly alters their responsiveness to most studied tobacco control policies in terms of quit attempts. We find that weight control belief reduces price-responsiveness among US female smokers (p≤0.1) and responsiveness to anti-smoking messaging (p≤0.01) ; in other words, increases in price and exposure to anti-smoking messaging lead to fewer quit attempts for those who have the weight control belief than for those who do not. More specifically, while a 10% increase in cigarette prices is associated with about 6% increase in quit attempts among female smokers who do not hold the weight control belief, the associations between prices and quit attempts are insignificant among smokers who have such a belief. Similarly, while a 10% increase in the exposure to anti-smoking messaging is associated with a 12% increase in quit attempts among female smokers who do not have weight control belief, it is not associated with an increase in quit attempts among those who do have such a belief. In addition, although exposure to more restrictive bar and restaurant tobacco control policies is positively but not significantly associated with quit attempts among US female smokers who do not have the belief, the interaction term of weight control belief and these policies are significantly negative. We do not see any patterns for men.

Table 3.

The Associations between tobacco control policies and quit attempts by country, gender, and weight control belief.

| U.S. | Canada | U.K. | Australia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| All | Male | Female | All | Male | Female | All | Male | Female | All | Male | Female | |

| Prices | 0.14** (0.07) [0.30] | 0.03 (0.10) [0.07] | 0.27*** (0.09) [0.58] | 0.02 (0.05) [0.05] | 0.01 (0.07) [0.02] | 0.02 (0.07) [0.06] | 0.10 (0.22) [0.46] | 0.22 (0.31) [1.04] | −0.05 (0.29) [−0.23] | −0.10 (0.21) [−0.35] | −0.34 (0.30) [−1.22] | 0.19 (0.29) [0.65] |

| Price/Belief Interaction | −0.15 (0.11) [−0.10] | −0.10 (0.19) [−0.06] | −0.25* (0.14) [−0.20] | −0.00 (0.08) [−0.00] | −0.06 0.04 [−0.05] | 0.02 (0.10) [0.02] | −0.89*** (0.33) [−1.43] | −2.08*** (0.56) [−3.06] | −0.06 (0.40) [−0.11] | −0.06 (0.31) [−0.06] | −0.19 (0.49) [−0.19] | 0.06 (0.41) [0.07] |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Worksite Bans | 0.34 (0.39) [0.52] | 0.57 (0.59) [0.90] | 0.22 (0.49) [0.32] | −0.32 (0.22) [−0.46] | −0.75** (0.34) [−1.08] | 0.10 (0.29) [0.15] | 0.63 (0.45) [0.89] | 0.49 (0.68) [0.70] | 0.73 (0.62) [1.01] | −0.12 (0.32) [−0.18] | −0.68 (0.50) [−1.02] | 0.49 (0.41) [0.71] |

| Worksite Bans/Belief Interaction | −0.66 (0.48) [−0.30] | −0.49 (0.82) [−0.19] | −0.82 (0.58) [−0.45] | −0.05 (0.33) [−0.02] | 0.15 (0.54) [0.05] | −0.23 (0.41) [−0.13] | −0.68* (0.39) [−0.34] | −1.31* (0.70) [−0.60] | −0.25 (0.48) [−0.13] | 0.14 (0.39) [0.06] | 0.30 (0.64) [0.12] | −0.22 (0.48) [−0.10] |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Bar Bans | 0.08 (0.20) [0.10] | 0.13 (0.29) [0.16] | 0.08 (0.26) [0.10] | −0.17 (0.14) [−0.22] | −0.28 (0.19) [−0.37] | −0.01 (0.18) [−0.01] | −0.26 (0.36) [−0.28] | −0.31 (0.52) [−0.33] | −0.23 (0.48) [−0.24] | 0.19 (0.25) [0.23] | 0.51 (0.37) [0.64] | −0.13 (0.32) [−0.16] |

| Bar Bans/Belief Interaction | −0.29 (0.24) [−0.11] | 0.10 (0.39) [0.03] | −0.69** (0.29) [−0.31] | −0.01 (0.18) [−0.00] | 0.18 (0.29) [0.06] | −0.14 (0.22) [−0.07] | −0.52 (0.38) [−0.20] | −1.26 (0.97) [−0.43] | −0.12 (0.44) [−0.05] | 0.06 (0.34) [0.02] | 0.59 (0.55) [0.20] | −0.42 (0.42) [−0.17] |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Restaurant Bans | 0.30 (0.20) [0.45] | 0.47 (0.29) [0.72] | 0.16 (0.27) [0.23] | 0.17 (0.24) [0.25] | 0.37 (0.36) [0.55] | 0.02 (0.32) [0.03] | 0.10 (0.48) [0.14] | 0.43 (0.71) [0.57] | −0.27 (0.65) [−0.35] | 0.05 (0.45) [0.07] | −0.33 (0.66) [−0.53] | 0.56 (0.61) [0.87] |

| Restaurant Bans/Belief Interaction | −0.27 (0.28) [−0.12] | 0.15 (0.45) [0.06] | −0.67* (0.34) [−0.36] | −0.07 (0.23) [−0.03] | 0.13 (0.37) [0.04] | −0.16 (0.28) [−0.09] | −0.41 (0.46) [−0.19] | −1.41 (1.12) [−0.60] | 0.24 (0.55) [0.12] | 0.00 0.59 [0.00] | 0.62 (0.97) [0.27] | −0.82 (0.75) [−0.41] |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Anti-smoking Messaging | 0.11 (0.21) [0.28] | −0.16 (0.30) [−0.44] | 0.49* (0.28) [1.23] | 0.38** (0.19) [1.02] | 0.44 (0.28) [1.17] | 0.36 (0.26) [0.97] | 0.50** (0.24) [1.33] | 0.38 (0.35) [1.04] | 0.57* (0.32) [1.49] | 0.29** (0.15) [0.82] | 0.60*** (0.22) [1.67] | −0.06 (0.20) [−0.17] |

| Anti-smoking Messaging/Belief Interaction | −0.56** (0.28) [−0.45] | −0.29 (0.47) [−0.19] | −0.98*** (0.35) [−0.93] | −0.11 (0.26) [−0.09] | 0.18 (0.42) [0.11] | −0.33 (0.33) [−0.34] | −0.66*** (0.20) [−0.62] | −1.24*** (0.34) [−1.06] | −0.24 (0.26) [−0.25] | −0.05 (0.18) [−0.04] | 0.21 (0.29) [0.16] | −0.27 (0.23) [−0.23] |

|

| ||||||||||||

| N | 4266 | 1786 | 2480 | 5060 | 2216 | 2844 | 4999 | 2194 | 2805 | 5451 | 2453 | 2998 |

Note: marginal estimates (β) are reported. Robust Standard errors are in parentheses. Elasticity estimates are in square brackets. Regressions were conducted separately for each tobacco control policy.

0.05 < p ≤ 0.1,

0.01 < p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01.

Table 3 also shows that in Canada and Australia weight control belief does not seem to alter policy responsiveness. In the UK, while a 10% increase in exposure to anti-smoking messaging is significantly associated with a 13% increase in quit attempts in the pooled sample of male and female smokers, weight control belief significantly reduces the responsiveness to anti-smoking messaging in the sense that smokers who have such a belief are not responsive to anti-smoking messaging. Although exposure to worksite smoking bans and increasing prices are positively but not significantly associated with quit attempts among UK smokers who do not have the belief, the interaction term of weight control belief and these policies are significantly negative.

In sum, the results presented above suggest very different policy responsiveness by the weight control belief among US female smokers and among UK smokers. We do not find positive and significant associations between some tobacco control policies and quit attempts in some countries, which is likely due to the lack of subnational policies or policy change during the study period. Nevertheless, our results pertaining to the US female smokers illustrate that there is a heterogeneity in policy-responsiveness between those who have the weight control belief and those who do not. Therefore, weight concerns may contribute to the lack of responsiveness among US females found in the existing literature. This is also consistent with a recent finding which suggests that US female smokers with weight control belief tend to be less price-responsive in reducing cigarette consumption than those without the belief as price increases [15].

Conclusions

This study marks the first effort to answer whether weight concerns alter smokers’ responsiveness to tobacco control policies in making a quit attempt. Using data taken from ITC 4 country project in the U.S., the U.K., Australia, and Canada, we analyzed the policy impact by allowing it to differ by whether the smoker agrees that smoking helps weight control. We find that weight control belief significantly attenuates policy impacts on promoting quit attempts among US female smokers. Our findings in part explain why many previous studies have found that female US smokers do not seem to respond to price increases by reducing their smoking participation. In other words, weight concerns do moderate these smokers’ responsiveness to tobacco control policies to discourage quit attempts and keep them continuing to smoke. Similar patterns are also found in pooled samples of both UK female and male smokers, but not among smokers in Australia and Canada.

We acknowledge that there are some limitations to this study. First, we constructed our weight control belief measure using self-reported answers which may contain some measurement errors and errors from respondents who reported “neither agree nor disagree”. However, we conducted some sensitivity analyses by categorizing “neither agree nor disagree” as having the weight control belief and most of results remain similar. Second, our weight control belief measure is not specific enough to answer whether it is a concern of post-cessation weight gain or other weight related concerns and respondents’ weights or BMIs are not available in the data. Third, for most countries there is not enough variation in policy measures that can be employed to identify policy impacts. Therefore, although most of our policy estimates are positive, they are not significant. Nevertheless, we were still able to detect some difference in the policy impact by weight control belief among US female smokers and UK smokers. Fourth, since we only have 4 waves of data and ITC is a longitudinal survey, there is not sufficient variation of quitting over time for us to examine the interaction effect of weight concerns and policy responsiveness by quitting.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide important empirical evidence that the efficacy of tobacco control policies in certain sub-populations may be greatly reduced by some unobserved smoking related factors such as weight concerns. The insignificant or small price impact on female smokers in the US, to some extent, can be attributed to weight concerns that are very prevalent among females. Identifying these potential factors is crucial to improving the effectiveness of tobacco control policies in certain sub-populations. Since we found that weight concerns do in fact attenuate policy responsiveness in certain populations, policy makers should take this into account and alleviate weight concerns to enhance the effectiveness of existing tobacco control policies on promoting quit attempts and reducing smoking.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

This paper provides the first analysis on whether weight concerns alter smokers’ responsiveness to tobacco control policies in making a quit attempt.

Among US female smokers and UK smokers, weight concerns do moderate smokers’ responsiveness to tobacco control policies to discourage quit attempts and keep them continuing to smoke.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ITC Principal Investigators of the US (K. Michael Cummings and Andrew Hyland), the UK (Gerard Hasting and Ann McNeill), Canada (Geoffrey T. Fong), Australia (Ron Borland). We would like to acknowledge all country team members especially the interviewers in the face-to-face data collection. All errors are our own.

Funding statements:

The data collection for the ITC Project is supported by grants R01 CA 100362 and P50 CA111236 (Roswell Park Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center, and P01 CA138389, R01 CA090955) from the National Cancer Institute of the United States, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (57897, 79551, and 115016), Commonwealth Department of Health and Aging, Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (014578), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (265903), the International Development Research Centre (104831-002). A Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute for the third author.

Footnotes

Contributor statement:

CS, FJC, GTF, MT, and MS planned the work described in the article. CS and WR conducted the analyses, wrote the draft, and reported the work after discussion with other authors. CS is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patent consent: Obtained.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approvals:

All ITC Surveys were conducted with the approval of the Office of Research Ethics Committee at the University of Waterloo, Canada and the respective internal ethics board for each country.

References

- 1.Borrelli B, Mermelstein R. The role of weight concern and self-efficacy in smoking cessation and weight Gain among smokers in a clinic-based cessation program. Addict Behav. 1998;23(5):609–622. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00014-8. published Online First: 10 December 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisinger C, Jorgensen T. Weight concerns and smoking in a general population: The Inter99 study. Prev Med. 2007;44(4):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.014. published Online First: 11 January 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomerleau CS, Zucker AN, Stewart AJ. Characterizing concerns about post-cessation weight gain: results from a national survey of women smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):51–60. doi: 10.1080/14622200125675. published Online First: February 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukhopadhyay S, Wendal J. Is post-smoking-cessation weight-gain a significant trigger for relapse? Appl Econ. 2011;43(24):3449–3457. doi: 10.1080/0003684100365243004. published Online First: 4 Nov 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aubin H, Berlin I, Smadja E, et al. Factors associated with higher body mass index, weight concern and weight gain in a multinational cohort study of smokers intending to quit. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(3):943–957. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6030943. published Online First: 2 Mar 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siahpush M, Singh GK, Tibbits M, et al. It is better to be a fat ex-smoker than a thin smoker: findings from the 1997–2004 National Health Interview Survey-National Death Index linkage study. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050912. Published Online First: 10 April 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiolero A, Faeh D, Paccand F, et al. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution and insulin resistance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):801–809. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John U, Hanke M, Rumpf HJ, et al. Smoking status, cigarettes per Day, and their relationship to overweight and obesity among former and current smokers in a national adult general population sample. Int J Obesity (Lond) 2005;29:1289–1294. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.08030285. published Online First: 5 July 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson RL, Margetts BM, Wood DA, et al. Cigarette smoking and food and nutrient intakes in relation to coronary heart disease. Nutr Res Rev. 1992;5:131–2. doi: 10.1079/NRR19920011. published Online First: 14 December 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serdula MK, Byers T, Mokdad AH, et al. The association between fruit and vegetable intake and chronic disease risk factors. Epidemiology. 1996;7:161–5. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kvaavik E, Meyer HE, Tverdal A. Food habits, physical activity and body mass index in relation to smoking status in 40–42 year old Norwegian women and men. Prev Med. 2004;38:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.020. published Online First: 7 November 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cawley J, Markowitz S, Tauras J. Lighting up and slimming down: the effects of body weight and cigarette prices on adolescent smoking initiation. J Health Econ. 2004;23:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.12.003. published Online First: 8 February 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cawley J, Markowitz S, Tauras J. Body weight, cigarette prices, youth access laws and adolescent smoking initiation. East Econ J. 2006;32(1):149–170. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cawley J, Scholder SV. NBER Working Paper No. 18805. 2013. The demand for cigarettes as derived from the demand for weight control. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT, et al. The Impact of Weight Control Belief on Cigarette Consumption among Adults: Findings from the ITC Project. American Economic Association; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. Jan 3–5, [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaloupka FJ, Warner KE. The Economics of Smoking. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Amsterdam, North-Holland: Elsevier B.V; 2000. pp. 1539–1627. published Online First: 8 February 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control, Vol. 14: Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kostova D. A (nearly) global look at the dynamics of youth smoking initiation and cessation: the role of cigarette prices. Appl Econ. 2013;45(28):3943–3951. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2012.736947. published Online First: 21 Nov 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostova D, Chaloupka FJ, Shang C. A duration analysis of the role of cigarette prices on smoking initiation and cessation in developing countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2014 Mar; doi: 10.1007/s10198-014-0573-9. published Online First: 9 Mar 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Guidon GE, et al. American Society of Health Economists. Los Angeles, CA: 2014. Jun 22–25, Smoking initiation and cessation in India – a duration analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Kostova D. Who Quits? An Overview of Quitters in Low- and Middle- Income Countries. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt179. published Online First: 16 Jan 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tauras JA, Huang J, Chaloupka FJ. Differential impact of tobacco control policies on youth sub-populations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:4306–4322. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10094306. published Online First: 12 Sep 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaloupka FJ, Pacula RL. Sex and race differences in young people’s responsiveness to price and tobacco policies. Tob Control. 1999;8:373–377. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.4.373. published Online First: 1 December 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrelly MC, Bray JW, Pechacek T, et al. Response by adults to increases in cigarette prices by demographic characteristics. South Econ J. 2001;68(1):156–165. doi: 10.2307/1061518. published Online First: July 2001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrelly MC, Bray JW. Response to increases in cigarette prices by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(29):605–609. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.1979. published Online First: 5 October 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hersch J. Gender, income levels, and the demand for cigarettes. J Risk Uncertain. 2000;21(2/3):263–282. doi: 10.1023/A:1007815524843. published Online First: 1 November 2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaloupka FJ. NBER Working Paper No. 3267. 1990. Feb, Men, women, and addiction: the case of cigarette smoking. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control. 2011;20(3):235–238. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039982. published Online First: 29 November 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Johnsen LA, Carpentier MR, King AC. Race and sex associations to weight concerns among urban African Americans and Caucasian smokers. Addic Behav. 2011;36:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.001. published Online First: 6 August 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii3–iii11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Twardella D, Loew M, Rothenbacher D, et al. The impact of body weight on smoking cessation in German adults. Prev Med. 2006;42(2):109–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.008. published Online First: 5 December 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Zahra N, et al. The distribution of cigarette prices under different tax structures: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-050966. Published Online First: 21 Jun 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley& Sons, Inc; 2006. pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zegar SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. doi: 10.2307/2531734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.