Abstract

Recent advances in the developmental epidemiology, neurobiology and treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders have increased our understanding of these conditions and herald improved outcomes for affected children and adolescents. This article reviews the current epidemiology, longitudinal trajectory, and neurobiology of anxiety disorders in youth. Additionally, we summarize the current evidence for both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic treatments of fear-based anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized, social and separation anxiety disorders) in children and adolescents. Current data suggest that these disorders begin in childhood and adolescence, exhibit homotypic continuity and increase the risk of secondary anxiety and mood disorders. Psychopharmacologic trials involving selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs) are effective in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders and have generally demonstrated moderate effect sizes. Additionally, current data support cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are efficacious in the treatment of these conditions in youth and that combination of CBT + an SSRI may be associated with greater improvement than would be expected with either treatment as monotherapy.

Keywords: antidepressant, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), anxiety disorders, separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SoP), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

Introduction

Affecting between 15-20% of youth, anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent psychiatric conditions in children and adolescents [1,2]. Moreover, from a public health standpoint, these disorders, when present in youth, increase the risk of suicide attempts [3,4] and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Additionally, longitudinal data suggest that anxiety disorders in youth predict a range of psychiatric disorders later in life, including other anxiety disorders, substance use disorders and depression [5,6].

To date, most treatment studies of pediatric anxiety disorders have largely focused on anxiety symptoms as a homogenous entities and, as such, many psychopharmacologic treatment investigations have included individuals with “pediatric anxiety disorder triad” disorders (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], social phobia [SoP]/social anxiety disorder and separation anxiety disorder [SAD]). It is further noteworthy that accumulating clinical, phenomenologic, epidemiologic data support this classification. Specifically, the “triad anxiety disorders” frequently co-occur [7] exhibit very similar trajectories [8] share neurophysiology [9,10] and respond similarly to both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic treatments (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) and cognitive behavioral psychotherapy [11].

Herein, we will review the developmental epidemiology, neurobiology, assessment and treatment (both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic) of youth with anxiety disorders as well as recent, long-term treatment data and emerging data concerning predictors of treatment response. Ultimately, to achieve the optimal outcome in any individual child or adolescent, a personalized approach is necessary, based on as much knowledge as possible of the developmental epidemiology, the personal and family history, signs and symptoms, pathophysiology, clinical phenotype, comorbidities, as well as the family, home and school environment. Frequently, these data will result in a multi-pronged approach to treatment—which may include one or more psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic interventions.

Developmental Epidemiology and Course of Pediatric Anxiety Disorders

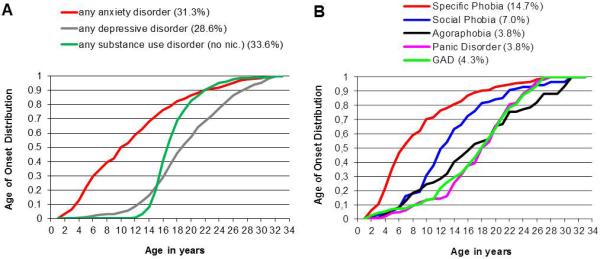

Accumulating data—from both retrospective and prospective studies—suggest that anxiety disorders are both the most frequent psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents and represent the “earliest of all forms of psychopathology” [12]. Mostly due to the frequent, early emerging specific phobias, the onset of the first or any anxiety disorder is usually in childhood, and thus, considerably earlier than the onset of depressive or substance use disorders (Figure 1A). However, there is considerable heterogeneity in the onset of the specific anxiety disorders with GAD, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) mostly emerging in adolescence (Figure 1B). Overall, anxiety disorders are more prevalent in girls compared to boys, although it is noteworthy that sex differences are accentuated by development, with prevalence ratios reaching 2-3:1 by adolescence [2,6,13,14].

FIGURE 1. The age of onset distribution of (A) anxiety, depressive and substance use disorders and (B) specific anxiety disorders at age 33, and estimated cumulative incidence rates at age 33 (in parenthesis).

Data from the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology (EDSP) Study. Adapted from [8].

Although anxiety disorders with onset in childhood or adolescence may spontaneously remit, the course of pediatric anxiety disorders is overall considered to be chronic-and persistent. This is due to evidence from several decades of data suggesting that anxiety disorders in childhood or adolescence strongly predict the presence of the same condition (homotypic continuity) in later in life [6,15-18]. The individual course, however, is often “waxing and waning” and “syndrome shifts” to other anxiety syndromes frequently occur [19]. The presence of “pure” anxiety disorders decreases with age in favor of patterns with multiple anxiety disorders, and by late adolescence or early adulthood, secondary psychopathology, such as depressive or substance use disorders have frequently developed (heterotypic continuity) [6,16,20-23]. Thus, early anxiety manifestations are at the outset of a “cascade of psychopathology” suggesting the need for early recognition and treatment [24,25]. In addition to adverse long-term psychopathological outcomes, child and adolescent anxiety disorders were linked with poor long-term functioning and general health as well as interpersonal, financial, and educational difficulties [17,26] in addition to suicidality [17,27].

Neurobiology of Pediatric Anxiety Disorder

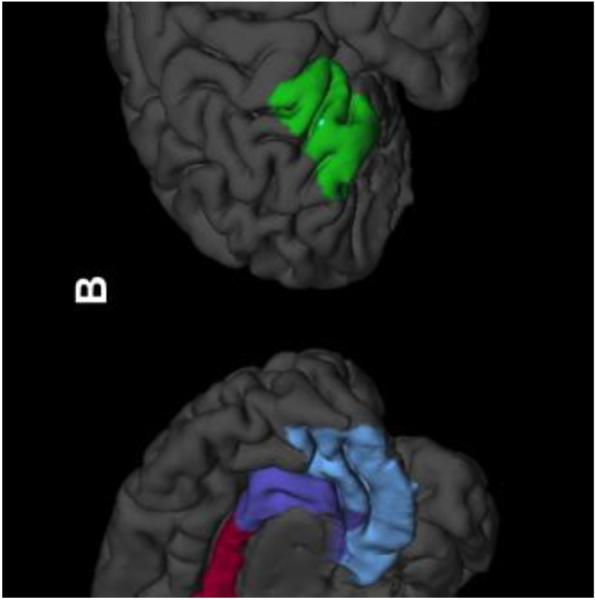

Considerable advances have been made in the understanding of the neurobiology of pediatric anxiety disorders over the past decade (for reviews see [9,28]). In general, these studies implicate dysfunction in prefrontal-amygdala based circuits, although, a myriad of both functional and structural neuroimaging studies reveal dysfunction (or abnormalities) in default mode networks and posterior structures, including the posterior cingulate, precuneus and cuneus (Figure 2). Among the structures which are most frequently implicated in the pathophysiology of pediatric anxiety disorders, the amygdala—which is charged with the initiation of central fear responses—is frequently “overactivated” in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of youth with fear-based anxiety disorders. However, the implication of the amygdala-based dysfunction extends beyond its activity and functional responsiveness to its connectivity. In this regard, intrinsic functional connectivity networks, including connectivity to the medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and cerebellum have been described. In addition to the amygdala, the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex has been examined in numerous studies of youth with fear-based anxiety disorders. Importantly, this structure regulates amygdala activity and plays a pivotal role in extinction in the context of fear conditioning and responds in tandem with the amygdala to emotional probes. It is further noteworthy that this structure may serve a lynchpin function in pediatric anxiety disorders. As such, the VLPFC is not only hyperactivated in youth with anxiety disorders, but the degree of activation is inversely proportional to the severity of anxiety symptoms, consistent with the notion that the VLPFC plays compensatory role in youth with anxiety (for review see [9]). Consistent with this notion, fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are associated with increases in activity of this structure in adolescents with anxiety [29]. Finally, the cingulate cortex which girdles the limbic system and subserves motivation and cognitive control is hyperactivated in youth with anxiety disorders [30] and that glutamatergic tone within the anterior cingulate cortex directly correlates with the severity of anxiety in adolescents with GAD [31].

FIGURE 2. Structures and regions implicated in pediatric patients with fear-based anxiety disorders.

The cuneus (yellow), precuneus (light green), dorsal anterior cingulate (red), pre/subgenual anterior cingulate (purple) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (light blue) are show medially in A, while the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC, lime green) is shown in the left lateral view in B. Adapted from [28].

Screening and Assessment

Current practice parameters from the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry [32] recommend screening for anxiety symptoms, rating the severity of the anxiety symptoms and functional impairment in youth with anxiety disorders and carefully assessing for co-morbid psychiatric conditions as well as for general medical conditions (e.g., hyperthyroidism) that may mimic anxiety symptoms. Moreover, the evaluation of the pediatric patient with suspected anxiety should allow anxiety disorders to be differentiated from developmentally appropriate worries, fears, and responses to stressors. Additionally, stressors or traumas should be considered to determine their contribution to the development or maintenance of anxiety symptoms. Finally, it is critical to consider that anxiety-related symptoms such as crying, irritability, or tantrums and be misinterpreted by adults as oppositionality or disobedience; these behaviors represent the child’s distress and efforts to avoid the anxiety-provoking stimulus.

Several well-studied child self-report screening measures for anxiety exist and may be used in patients >8 years of age. First, the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children [33], and the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) [34], and the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) [35] were developed to be sensitive and specific for assessing anxiety in youth and are useful in clinical practice to monitor treatment progress [36]. The Preschool Anxiety Scale is a parent report adapted from the SCAS that was developed for screening for anxiety in young children (ages 2.5 to 6.5). The SCARED and SCAS are available online/free access. Second, the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, which is frequently utilized as a primary or secondary outcome measure in psychopharmacologic trials of youth, is a clinician-rated measure used to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms and change over time [37]. Third, with regard to social phobia or social anxiety, the Social Anxiety Scale, the Social Worries Questionnaire, and the social phobia subscale of SCARED are brief screening measures for social phobia/social anxiety symptoms. Fourth, a set of novel dimensional anxiety scales was recently generated during the DSM revision process to support clinical decision-making and monitoring treatment progress (www.psychiatry.org/dsm5). These self-rated scales can be used for children aged 11 or older and comprise the core constructs of fear and anxiety together with cognitive, physical and behavioral symptoms in a consistent and brief way, using a common template for each of the anxiety disorders [38].

Psychological Treatments

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Well-regarded as an effective evidence-based treatment for childhood anxiety disorders, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has several key components: psychoeducation of child and caregivers regarding the nature of anxiety; techniques for managing somatic reactions including relaxation training and diaphragmatic breathing; cognitive restructuring by identifying and challenging anxiety-provoking thoughts; practicing problem-solving for coping with anticipated challenges; systematic exposure to feared situations or stimuli, including imaginal, simulated, and in vivo methods, with special focus on desensitization to feared stimuli; and relapse prevention plans [36]. To date, a few studies have evaluated the efficacy of CBT either alone or in combination with psychopharmacologic treatment for childhood anxiety disorders [7,39]. In a large, multisite study of youth with moderate to severe GAD, SoP and SAD, the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS), 488 children and adolescents (aged 7-17 years) were randomized to one of three treatment groups (sertraline monotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT], or sertraline + CBT) for 12 weeks [7]. In terms of clinical improvement and symptom severity, all treatment groups were superior to placebo (24%), and the combination therapy (sertraline + CBT) was significantly more efficacious (81%) than either group treated with either medication (55%) or CBT (60%) alone. The 24- and 36-week follow-ups in CAMS revealed over 80% of acute responders maintained their positive response at both 24 and 36-weeks [40]. During the follow-up period, participants continued in active treatment with sertraline, CBT booster sessions or both. Finally, the naturalistic 6-year follow-up study of this sample (n=288) revealed that these treatment effects were durable and sustained, with remission rates of 48.8%, 51.9%, and 45.8% for combination therapy, sertraline only, and CBT only, respectively [41]. Alternatively, nearly half of the acute responders relapsed during the follow-up period. The authors argue that many youth with anxiety disorders require intensive or extended treatment to maintain acute treatment gains [41].

Beidel and colleagues [39] evaluated the efficacy of Social Effectiveness Therapy for Children (SET-C) versus fluoxetine or placebo in children and adolescents aged 7-17 with social phobia. SET-C was more effective than placebo on primary outcome measures and specific symptom measures. Additionally, SET-C was superior to fluoxetine in terms of rate of treatment response (79% versus 36.4%, p<0.001), lack of posttreatment diagnosis, and higher end-state functioning [39]. Finally, CBT has now been examined in very young children with anxiety disorders [42]. Sixty four pre-schoolers, aged 4-7 years, were randomized to a parent-child CBT intervention or a monitoring-only control condition for a duration of six months. The response rate of children in the CBT group (defined as much or very much improved on the CGI-Anxiety scale) was 69%, compared to 32% for children in the control group. Additionally, 59% of children CBT-treated were free of all anxiety diagnoses following treatment (vs 18% of controls) [42].

Mindfulness-Based Psychotherapies

Mindfulness, the “the intentional, accepting, and non-judgmental focus of one’s attention on the emotions, thoughts, and sensations occurring in the present moment” [43], has been utilized as the basis for a myriad of programs over the last several decades to promote health and well-being in both adults and youth with anxiety disorders. Two approaches in particular have been used to increase psychological health: MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction) and MBCT (mindfulness based cognitive behavioral therapy) [44]. Both MBCT and MBSR use regular mindfulness meditation practices to develop mindfulness skills. Moreover, these psychotherapeutic interventions show promise for the treatment of anxiety disorders. In this regard, randomized, controlled trials in anxious adults have shown statistically significant improvement in symptoms of GAD [45-47], social anxiety [48-50], specific phobia [51], and panic disorder [45]. Mindfulness-based interventions have also shown effective in studies looking at a heterogeneous group of anxiety disorders [52,53]. At least one study has shown mindfulness to be as effective as CBT for social anxiety disorder [54].

In children and adolescents, studies of mindfulness-based interventions have been more limited. Catani et al. [55] found meditation-based relaxation to be as effective as trauma-focused CBT in the treatment of children with PTSD from war and tsunami in Sri-Lanka. Lierh & Diaz [56] found a mindfulness intervention to be effective in decreasing symptoms of anxiety and depression in a group of minority children. Other studies have shown effectiveness of mindfulness-based treatments in a variety of mental health problems in children [44] and open-label studies suggest that group-based MCBT may be effective for the treatment of adolescents with generalized, social or separation anxiety disorders who are at risk for developing bipolar disorder. Given the acceptability and tolerability of mindfulness-based interventions, as well as their demonstrated effectiveness thus far, such treatments for anxiety in children is an exciting area that warrants further investigation.

Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Psychodynamic psychotherapy has been evaluated in youth with anxiety disorders and recently subjected controlled trials. In one trial of 4-10 year old children with anxiety disorders [57], using a quasi-experimental wait-list children (N=30) with were treated with 20-25 sessions of manualized, short-term Psychoanalytic Child Therapy (PaCT). In this study 67% of patients no longer met criteria for any anxiety disorder compared to 0 children in the wait-list group. In parallel, internalizing and total problems significantly declined during treatment and gains were maintained at 6 months, post-treatment [57]. Fonagy and Target [58] examined the effect of intensity of psychodynamic psychotherapy. In this sample of 763 patients at the Anna Freud Center, several disorders were associated with differential responses with regard to the intensity of psychotherapy. Specifically, overanxious disorder—the DSM-III forerunner of GAD—responded better to high intensity psychotherapy, but similar differences in effect were not observed for simple phobias or separation anxiety disorder.

Psychopharmacologic Interventions

The aggressive evaluation of serotonergic antidepressants in youth with anxiety disorders is consistent with the evidence that these medications dampen fear responses in pre-clinical models of anxiety [59], and is likely driven by evidence supporting their use in adults with anxiety disorders as well as by their evidence for related psychiatric syndromes in youth, including major depressive disorder, with which anxiety disorders often co-occur.

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine reduces anxiety in youth with triad anxiety disorders (mean age: 11.8±3 years, N=74) over the course of 12 weeks of treatment [60]. In this trial, fluoxetine was initiated at 10 mg/day and titrated to a maximum fixed-dosage of 20 mg/day following the first week of treatment. Fluoxetine demonstrated significant improvement in anxiety symptoms and was generally well-tolerated. Adverse effects reported include nausea, abdominal pain, drowsiness and headaches. Additionally, Beidel and colleagues [39] examined the efficacy of fluoxetine and Social Effectiveness Therapy for Children (SET-C) in a 12-week, placebo-controlled study in youth (mean age: 11.6±2.6 years, N=122) with SoP (primary diagnosis). Patients were treated with fluoxetine (n=33), SET-C (n=57) or placebo (n=32) and fluoxetine was initiated at 10 mg/day (2 weeks), then titrated, sequentially, to 40 mg daily. Fluoxetine was superior to placebo and SET-C was statically superior to both fluoxetine and placebo. In terms of side effects in this trial of social phobia patients, only nausea occurred more frequently in patients receiving fluoxetine.

Fluvoxamine

Fluvoxamine has been examined in children and adolescents (aged 6-17 years, N=128) with mixed anxiety disorders (GAD, SoP and/or SAD) in an 8-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study [61]. Fluvoxamine-treated patients exhibited a statistically significant improvement in PARS score compared to youth receiving placebo. Fluvoxamine was well-tolerated, and there were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between placebo-treated patients and those receiving fluvoxamine.

Paroxetine

Wagner and colleagues [62] treated children with SoP, aged 8-17 years, with flexibly dosed paroxetine over the course of a 16-week, multi-center, parallel group study. Paroxetine was initiated at 10 mg/day and then flexibly dosed to a maximum of 50 mg/day. Patients receiving paroxetine exhibited a greater response rate (CGI-I: 77.6% of the paroxetine-treated vs. 33.8% of placebo-treated patients, p<0.001) and, in this sample, paroxetine was well-tolerated. However, decreased appetite, vomiting and insomnia were observed and 4 paroxetine-treated patients (and 0 placebo-treated patients) experienced emotional lability and suicidal ideation.

Sertraline

One 9-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of children and adolescents with GAD, aged 5-17 years examined the efficacy of fixed-dose treatment with sertraline [63]. In this trial, sertraline was initiated at 25 mg/day for 1 week and then increased to 50 mg/day for the subsequent 8-weeks. Sertraline treatment was associated with statistically significant improvements in anxiety symptoms (Hamilton Anxiety Scale Score (HAM-A), lower symptom severity (i.e., lower CGI-S scores) as well as greater improvement (i.e., higher CGI-I scores). In this study, there were no significant differences in adverse events between sertraline- and placebo-treated patients. Walkup and colleagues examined the efficacy of sertraline in the Child-Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS) [7], which involved a sample of 488 children and adolescent, aged 7-17 years, with GAD, SoP or SAD or a combination of these disorders, who received sertraline (n=133), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT, n=139), a combination of the sertraline and CBT (n=140) or placebo (n=76) over the course of 12 weeks. Sertraline + CBT (81%) was statistically superior to sertraline monotherapy (55%) and CBT monotherapy (60%) in terms of clinical improvement (i.e., CGI-I score) and symptom severity (i.e., PARS score). Additionally, sertraline and CBT monotherapy were superior to placebo (24%). Recently, the long-term extension study of CAMS was published—Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Extended Long-term Study (CAMELS) [41], in which 288 of the original 488 CAMS participants who were followed longitudinally. Patients who responded to acute treatment were more likely to be in remission and to have lower PARS scores. Also, of clinical importance, 50% of responders to acute treatment—regardless of type—achieved remission over the follow-up interval.

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine ER was evaluated in youth with GAD and SoP. In an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of patients, aged 6-17 years with GAD (N=320) [64]. Over the course of treatment GAD symptoms significantly improved relative to placebo and side effects were consistent with the known side effect profile of venlafaxine and included anorexia and somnolence, increases in heart rate and blood pressure, as well as weight loss. Also, 2 patients who received venlafaxine (compared to 0 patients receiving placebo) reported suicidal ideation/suicide attempt. March and colleagues [65] examined venlafaxine ER in children and adolescents with SoP. This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial studied a 16-week course of venlafaxine in children and adolescents (aged 8-17 years, mean age: 13.6±3.0 years, N= 293,). Venlafaxine was initiated at 37.5 mg/day and titrated according to body weight to an average of 2.6-3.0 mg/kg (maximum dose: 225 mg/day for patients ≥50 kg). Efficacy measures included the Social Anxiety Scale, child or adolescent version (SAS-CA) and CGI-I. Venlafaxine-treated patients exhibited significant improvements in SoP symptoms compared to placebo-treated patients. Adverse effects of venlafaxine included weight loss (secondary to anorexia), nausea and dizziness. Further, 3 venlafaxine-treated patients (compared to 0 placebo-treated patients) developed suicidal ideation, although no suicides or suicide attempts occurred.

Duloxetine

Strawn and colleagues [66] evaluated the efficacy of duloxetine in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of children and adolescents with GAD, aged 7-17 years (N=272) over the course of 10 weeks. In this study, PARS severity for GAD scores as well as total PARS score, CGAS, CGI-I and CGI-S scores all improved over the course of treatment and this medication was recently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of GAD in youth aged 7-17 years. Significant side effects included nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, dizziness, cough, oropharyngeal pain and palpitations.

Recently, all randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of SSRI/SSNRIs in pediatric patients with fear-based anxiety disorders, were subjected to a meta analysis [67]. This meta-analytic evaluation suggests a modest effect size (Cohen’s d=0.62) and importantly, suggests that SSRIs may not be associated with a statistically significant risk of suicidality in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders. Moreover, in this meta-analysis of 1,673 patients, antidepressant treatment did not appear to be associated with an increase in all cause discontinuation (p=0.132). Nonetheless, treatment-emergent activation was more commonly associated with antidepressants (compared to placebo), although this only trended towards statistical significance (p=0.05) [67].

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs)

Prior the availability of newer antidepressant medications, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were frequently utilized for pediatric anxiety disorders, however, their role has subsequently been supplanted by the SSRIs and SSNRIs. Moreover, controlled trials of TCAs for youth with anxiety disorders have yielded conflicting results (Table 1). Specifically, clomipramine, which is efficacious in randomized, controlled trials of pediatric patients with OCD, only 1 randomized controlled trial exists for pediatric anxiety disorders. Moreover, the anticholinergic side effects, need for frequent cardiac monitoring, lethality in overdose, have limited their use clinically in pediatric populations.

Table 1.

Randomized Controlled Trials of Antidepressants in Children and Adolescents with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Phobia or Separation Anxiety Disorder.

| Medication class |

Study | Medication | Study design |

Group, N |

Study duration wks |

Age yrs |

Outcome measure |

Endpoint Dose mg/day |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSNRI | March et al, 2007 |

Venlafaxine ER | Flexible | 137 148 |

12* | 8-17 | SAS-CA | 142 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|||||||||

| Rynn et al, 2007 |

Venlafaxine ER | Flexible | 157 163 |

8 | 6-17 | PARS | NR | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Strawn et al, 2013 |

Duloxetine | Flexible | 135 137 |

10 | 7-17 | PARS | 53.6 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

| |||||||||

| SSRI | Walkup et al, 2008 |

Sertraline | Flexible | 133 76 |

12 | 7-17 | PARS | 133 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|||||||||

| Rynn et al, 2001 |

Sertraline | Fixed | 11 11 |

9 | 5-17 | HAM-A | 50 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Wagner et al, 2004 |

Paroxetine | Flexible | 163 156 |

16 | 12-17 | PARS | 32.6 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| RUPP et al, 2001 |

Fluvoxamine | Flexible | 63 65 |

8 | 6-17 | PARS | 2.9 ± 1** | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Beidel et al, 2007 |

Fluoxetine | Fixed | 33 32 | 12 | 7-17 | SPAI-C | 40 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Birmaher et al, 2003 |

Fluoxetine | Fixed | 37 37 |

12 | 7-17 | PARS | 20 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

| |||||||||

| TCAs | Gittelman- Klein and Klein, 1971 |

Imipramine | Flexible | 35 | 6-14 | Not reported |

100-200 | Medication > placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Klein et al, 1992 |

Imipramine | Flexible | 11 10 |

6 | 6-15 | Not reported | 75-275 | Medication = placebo |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Berstein et al, 2000 |

Imipramine | Flexible | 31 32 | 8 | ARC | 150-300 μg/L**** |

Medication + CBT > placebo + CBT |

||

DBPCT, double blind, placebo-controlled trial; SAS-CA, Social Anxiety Scale for Children & Adolescents; pbo, placebo; PARS, Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale; NR, not reported; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SPAI-C, Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children; ARC, Anxiety Rating for Children-Revised

This was a 16 week trial; however, 12 week data were used for the analyses described herein.

mg/kg/day, rather than mg/day.

§ Percentage reflects the entire sample, including adolescents treated with psychotherapy only.

† Reported as probability of achieving a CGI-S score = 2 at week 16.

^ Reported as difference in regression model with age and pre-treatment score as covariates.

∞ Reported as percentage of patients achieving a CGI-S score =4.

serum concentration of imipramine + desipramine

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines bind to the GABAA receptor and in doing so potentiate the effects of the endogenous, inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Thus, it is not surprising that for nearly two decades, benzodiazepines have been used to treat anxiety symptoms in youth. However, to date, the evidence for or against the use of benzodiazepines in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders has been limited to randomized, controlled studies in surprisingly few patients.

The efficacy of benzodiazepines in anxious youth has been evaluated in two randomized clinical trials. In youth with GAD, aged 8-17 years (mean age: 12.6 years, N=30), who were treated with alprazolam (or placebo), no statistically significant differences were observed in anxiety symptoms or in clinical global improvement between alprazolam-treated and placebo-treated youth [68]. However, alprazolam was associated with fatigue and dry-mouth. Additionally, Graae and colleagues [69] assessed the efficacy of clonazepam in pediatric patients with SoP and/or GAD (aged: 7-13 years, N=15). Clonazepam reduced anxiety symptoms to comparable levels as placebo, and no differences were detected in CGI-I scores between benzodiazepine- and placebo-treated youth. Finally, side effects, including irritability, drowsiness, and ‘oppositional behavior’ were common.

Other medications

The 5-HT1A agonist buspirone has been evaluated in a large, unpublished, study of pediatric patients with GAD who were aged 6-17 years (N=559). In this 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (Bristol-Meyers Squibb, 2010), patients were treatment with buspirone 15-60 mg/day (divided BID) and no statistically significant differences between buspirone and placebo were observed. However, buspirone was well tolerated and no serious adverse effects were more frequently reported in buspirone-treated patients compared to the placebo-treated patients.

Atomoxetine has been evaluated in youth with ADHD and a co-occurring anxiety disorders (SAD, GAD and/or SoP; PARS score ≥15) in a 12-week, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study [70]. Patients (aged 8-17 years, mean age: 12.0±3.0 years, N=176) were treated with atomoxetine which was titrated to 1.8 mg/kg/day (mean dose: 1.3 mg/kg/day). Reductions in both anxiety and ADHD symptoms were observed with atomoxetine treatment and this SNRI was well-tolerated, although decreased appetite was more frequently observed in atomoxetine-treated patients.

Finally, one double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of extended release guanfacine Nplacebo=21; Nguanfacine ER=62) in pediatric patients with GAD/SoP/SAD has recently been completed (NCT01470469, www.clinicaltrials.gov). This trial involved 12 weeks of treatment with extended release guanfacine (1-6 mg/day) or placebo and has been released.

Predictors of Treatment Response

Accumulating evidence suggests a constellation of “predictors” of treatment response in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. These predictors include demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics and family-system factors. In one study of youth aged 7-17 years with triad anxiety disorders who were treated with fluoxetine (or placebo), having a first-degree relative with an anxiety disorder was associated with poorer functional outcomes at endpoint (OR=3.3) [60]. In the CAMS, increased caregiver strain, a measure of the effect of caring for a child with emotional problems on the primary caregiver (e.g., increased time demands, financial strain, disruption of family relationships), predicted higher endpoint PARS score. Additionally, Ginsburg and colleagues [71] noted that older age predicted a decreased likelihood of remission in CAMS (OR=0.92, 95%, p=0.01), which was defined as the absence of all study entry diagnoses. Additionally, being Caucasian predicted an increased likelihood to enter remission (OR=2.07, p=0.003). Finally, the long-term, follow-up study of CAMS participants suggests that males as well as participants with better family functioning are more likely to be in remission approximately 6 years post-randomization [41].

Regarding baseline anxiety symptom severity, in fluoxetine-treated patients, more severe anxiety at baseline (Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale [CGI-S]>4) was significantly associated with a poorer functional outcome [60], while in other samples of SSRI-treated youth, baseline anxiety symptoms severity predicts SSRI nonresponse (OR=7.34) [72]. Further, more severe anxiety at baseline, as reported by both independent evaluators and parents, predicted higher PARS scores at week 12 in CAMS (p<0.01 and p=0.02, respectively) [73]. Additionally, the type of specific anxiety disorders appears to influence treatment response. Treatment response to fluoxetine in pediatric anxiety disorders is moderated by SoP diagnosis, at least with regard to clinical and functional response [60]. Moreover, in CAMS, having a principal diagnosis of SAD eliminated any advantage of sertraline (and CBT), relative to placebo, with regard to PARS score, although superiority of combined treatment (sertraline+CBT) compared to placebo was preserved [73]. Finally, in CAMS, a principal diagnosis of SoP was associated with a statistically equivalent decrease in PARS score in patients treated with sertraline ± CBT, but not in patients receiving CBT monotherapy (compared to placebo) [73], suggesting that for a primary diagnosis of SoP, medication may be a requisite treatment element. Finally, Masi and colleagues [72], observed, in a sample of youth 7-18 years (N=140) who were treated with fluoxetine, sertraline, or fluvoxamine for 12 weeks, 2 comorbidities predicted treatment nonresponse: conduct disorder (OR=6.39, 95% CI: 1.402-14.36, p=0.011) and bipolar disorder (OR=3.85, 95% CI: 1.00-9.90, p=0.050), while in CAMS, a diagnosis of a comorbid internalizing disorder attenuated the probability of achieving remission at endpoint [71].

Future Directions

While there has been a dramatic increase in the number of neuroimaging, genetic, as well as psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic studies involving anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, much work remains. In this regard, while current data suggest a basic neurocircuitry of anxiety disorders in youth, the relationship between dysfunction within these amygdala-prefrontal networks and risk, progression and treatment remains largely unknown. Moreover, while both psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic studies have established the efficacy for a number of treatments, data regarding predictors (either clinical, neurobiological or psychopharmacologic) of treatment response are brutally lacking. Relatedly, few studies have examined optimal “dosing” of either psychotherapeutic or psychopharmacologic treatments and little is known regarding next-step interventions for youth with anxiety disorders, who do not response to initial evidence-based strategies. Finally, the optimal duration of treatment for pediatric patients with anxiety disorders is generally unknown, with both psychopharmacolgic and psychotherapeutic studies being frequently focused on short-term, acute effects.

Conclusions

Anxiety disorders are both highly prevalent in youth and are associated with substantial morbidity and an increased risk of suicide attempts and self-injurious behavior. Moreover, these disorders are associated with dysfunction within a myriad of amygdala-based networks throughout the prefrontal cortex (for recent reviews see: [9,28]). Over the past several decades, screening and assessment tools have been developed to assist clinicians in identifying anxiety symptoms early and accurately establishing anxiety disorder diagnoses. Importantly, these disorders are amenable to treatment, both psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic and there has been a recent surge in evidence for exposure-based CBT and SSRIs/SSNRIs in the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Specifically, psychopharmacologic trials data in pediatric patients with non-OCD anxiety disorders suggest that SSRIs and SSNRIs are efficacious and well-tolerated. However, placebo-controlled studies do not support the efficacy of benzodiazepines or buspirone in the treatment of youth with anxiety disorders. Moreover, we are beginning to appreciate that certain clinical and demographic variables may ultimately predict successful treatment outcome, including a family history, baseline anxiety severity, and comorbidity.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Ms. Wehry and Dr. Hennelly report no biomedical conflicts of interest. Dr. Strawn has received research support from Edgemont, Eli Lilly, Shire, Forest Research Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Dr. Connolly has received research support from the NIMH

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169–84. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burnstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, Angold A. Proximal psychiatric rick factors for suicidality in youth: the Great Smoky Mountains study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1017–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson CM, Muehlenkamp JJ, Miller AL, Turner JB. Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(2):363–75. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beesdo-Baum K, Pine DS, Lieb R, Wittchen J. Mental disorders in adolescence and young adulthood: homotypic and heterotypic longitudinal associations. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 51st Annual Meeting; Hollywood, Florida. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Waslick B, Iyengar S, March JS, Kendall PC. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2753–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beesdo K, Pine DS, Lieb R, Wittchen H-U. Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):47–57. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackford JU, Pine DS. Neural substrates of childhood anxiety disorders: a review of neuroimaging findings. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21(3):501–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strawn JR, Wehry AM, DelBello MP, Rynn MA, Strakowski S. Establishing the neurobiologic basis of treatment in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2012a;29:328–339. doi: 10.1002/da.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall PC, Compton SN, Walkup JT, Birmaher B, Albano AM, Sherrill J, Ginsburg G, Rynn M, McCracken J, Gosch E, Keeton C, Bergman L, Sakolsky D, Suveg C, Iyengar S, March J, Piacentini J. Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(3):36–5. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;32:483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costello EJ, Copeland W, Angold A. Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: What changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(10):1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.•Beesdo-Baum K, Knappe S. Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012b;21(3):457–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.001. This paper describes the emergence and trajectory of anxiety disorders over the lifespan in children, adolescents and young adults. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner A, Egger HL, Erkanli A, Costello EJ, Foley DL, Angold A. What do childhood anxiety disorders predict? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(12):1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello J, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(9):1086–93. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregory AM, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Koenen K, Eley TC, Poulton R. Juvenile mental health histories of adults with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):301–308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittchen H-U, Lieb R, Pfister H, Schuster P. The waxing and waning of mental disorders: evaluating the stability of syndromes of mental disorders in the population. Compr Psychiatry. 2000a;41(suppl. 1):122–132. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(00)80018-8. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann P, Wittchen H-U, Höfler M, Pfister H, Kessler RC, Lieb R. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorder: A 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1211–1222. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, Stein MB, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen H-U. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(8):903–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittchen H-U, Kessler RC, Pfister H, Lieb R. Why do people with anxiety disorders become depressed? A prospective-longitudinal community study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl . 2000b;(406):14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, Beesdo K, Hofler M, Lieb R. What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(5):618–626. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shear MK, Bjelland I, Beesdo K, Gloster AT, Wittchen H-U. Supplementary dimensional assessment in anxiety disorders. Int J of Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16(Suppl.1):S52–S64. doi: 10.1002/mpr.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wittchen H-U, Knappe S, Schumann G. The psychological perspective on mental health and mental disorder research: introduction to the ROAMER work package 5 consensus document. Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(S1):15–27. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to adulthood: The Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beesdo-Baum K, Lieb R, Wittchen H-U. Anxiety disorders as early stages of malignant psychopathological long-term outcomes: results of the 10-years prospective EDSP study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013;54(8):e16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strawn JR, Dominick KC, Patino LR, Doyle CD, Picard PS, Phan KL. Neurobiology of pediatric anxiety disorders. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2014;1(3):154–160. doi: 10.1007/s40473-014-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maslowsky J, Mogg K, Bradley BP, McClure-Tone E, Ernst M, Pine DS, Monk CS. A preliminary investigation of neural correlates of treatment in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(2):105–11. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, Parrish JM, Adler A, Blair RJ, Fromm S, Charney DS, Leibenluft E, Ernst M, Pine DS. Abnormal attention modulation of fear circuit function in pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):97–106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strawn JR, Bitter SM, Weber WA, Chu WJ, Whitsel RM, Adler C, Cerullo MA, Eliassen J, Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. Neurocircuitry of generalized anxiety disorder in adolescents: a pilot functional neuroimaging and functional connectivity study. Depress Anxiety. 2012b;29(11):939–947. doi: 10.1002/da.21961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:267–283. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246070.23695.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):554–65. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1230–6. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spence SH. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:545–66. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velting ON, Setzer NJ, Albano AM. Update and advances in assessment and cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35:42–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1061–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Möller E, Majdandzic M, Craske MG, Bögels S. Dimensional assessment of anxiety disorders in parents and children for DSM-5. Intl J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(3):331–44. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Sallee FR, Ammerman RT, Crosby LA, Pathak S. SET-C versus fluoxetine in the treatment of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1622–32. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318154bb57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.•Piacentini J, Bennett S, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Albano AM, March J, Sherrill J, Sakolsky D, Ginsburg G, Rynn M, Bergman RL, Gosch E, Waslick B, Iyengar S, McCracken J, Walkup J. 24- and 36-week outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.010. This analyses describes long-term outcomes following an acute, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline, CBT or sertraline + CBT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ginsburg GS, Becker EM, Keeton CP, Sakolsky D, Piacentini J, Albnano AM, Compton SN, Iyengar S, Sullivan K, Caporino N, Peris T, Birmaher B, Moira R, March J, Kendall PC. Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(3):310–318. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirschfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, Blakely LR, Pollock-Wurman RA, McQuade J, DePetrillo L, Briesch J, Ollendick TH, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J. Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- to 7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(4):498–510. doi: 10.1037/a0019055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, Kushner K, Koehler R, Marlatt A. Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):266–94. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke CA. Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19.2:133–144. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YW, Lee SH, Choi TK, Suh SY, Kim B, Kim CM, Cho SJ, Kim MJ, Yook K, Ryu M, Song SK, Yook KH. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as an adjuvant to pharmacotherapy in patients with panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(7):601–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, Metcalf CA, Morris LK, Robinaugh DJ, Worthington JJ, Pollack MH, Simon NM. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):786–92. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koszycki D, Benger M, Shlik J, Bradwejn J. Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Werner K, Ziv M, Gross JJ. A randomized trial of MBSR versus aerobic exercise for social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(7):715–731. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bögels SM, Sijbers GFVM, Voncken M. Mindfulness and task concentration training for social phobia: A pilot study. J Cogn Psychother. 2006;20(1):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cassin SE, Rector NA. Mindfulness and the attenuation of post-event processing in social phobia: an experimental investigation. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(4):267–278. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.614275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hooper N, Davies N, Davies L, McHugh L. Comparing thought suppression and mindfulness as coping techniques for spider fear. Conscious Cogn. 2011;20(4):1824–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vøllestad J, Sivertsen B, Nielsen GH. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for patients with anxiety disorders: evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(4):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arch JJ, Ayers CR, Baker A, Almklov E, Dean DJ, Craske MG. Randomized clinical trial of adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for heterogeneous anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(4):185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Hawley LL, Huta V, Antony MM. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(12):889–898. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: a comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC psychiatry. 2009;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liehr P, Diaz N. A pilot study examining the effect of mindfulness on depression and anxiety for minority children. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;24(1):69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Göttken T, White LO, Klein AM, von Klitzing K. Short-term psychoanalytic child therapy for anxious children: a pilot study. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2014;51(1):148–58. doi: 10.1037/a0036026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fonagy P, Target M. Predictors of outcome in child psychoanalysis: a retrospective study of 763 cases at the Anna Freud Centre. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1996;44(1):27–77. doi: 10.1177/000306519604400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiser RS, Lebovitz RM. Monoaminergic mechanisms in aversive brain stimulation. Physiol Behav. 1975;15(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Monk K, Kalas C, Clark DB, Ehmann M, Bridge J, Heo, Brent DA. Fluoxetine for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(4):415–23. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000037049.04952.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group Fluvoxamine for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(17):1279–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner KD, Berard R, Stein MB, Wetherhold E, Carpenter DJ, Perera P, Gee M, Davy K, Machin A. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1153–62. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rynn MA, Siqueland L, Rickels K. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of children with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2008–14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rynn MA, Riddle MA, Yeung PP, Kunz NR. Efficacy and safety of extended-release venlafaxine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: two placebo-controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):290–300. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.March JS, Entusah AR, Rynn M, Albano AM, Tourian KA. A randomized controlled trial of venlafaxine ER versus placebo in pediatric social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(10):1149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.•Strawn JR, Prakash A, Zhang Q, Pangallo BA, Stroud CE, Cai N, Findling RL. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of duloxetine for the treatment of children (7-11 Years) and adolescents (12-17 Years) with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.008. accepted). This recent article describes the registration trial for the only USFDA approved antidepressant for GAD in children and adolescents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.•Strawn JR, Wehry AM, Keeshin BR, Welge J, DelBello MP. Antidepressant efficacy and tolerability in pediatric anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2014b doi: 10.1002/da.22329. (in press).This article represents the only meta-analysis of antidepressants in pediatric patients with non-OCD anxiety disorders and also examines treatment-emergent side effect profiles. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simeon JG, Ferguson HB, Knott V, Roberts N, Gauthier B, Dubois C, Wiggins D. Clinical, cognitive, and neurophysiological effects of alprazolam in children and adolescents with overanxious and avoidant disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):29–33. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graae F, Milner J, Rizzotto L, Klein RG. Clonazepam in childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(3):372–6. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Geller D, Donnelly C, Lopez F, Rubin R, Newcorn J, Sutton V, Bakken R, Paczkowski M, Kelsey D, Sumner C. Atomoxetine treatment for pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180ca8385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ginsburg GS, Kendall PC, Sakolsky D, Compton SN, Piacentini J, Albano AM, Walkup JT, Sherrill J, Coffey KA, Rynn MA, Keeton CP, McCracken JT, Bergman L, Iyengar S, Birmaher B, March J. Remission after acute treatment in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: findings from the CAMS. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(6):806–13. doi: 10.1037/a0025933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masi G, Pfanner C, Mucci M, Berloffa S, Magazu A, Parolin G, Perugi G. Pediatric social anxiety disorder: predictors of response to pharmacological treatment. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):410–4. doi: 10.1089/cap.2012.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.•Compton SN, Peris TS, Almirall D, Birmaher B, Sherrill J, Kendall PC, March JS, Gosch EA, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, Piacentini JC, McCracken JT, Keeton CP, Suveg CM, Aschenbrand SG, Sakolsky D, Iyengar S, Walkup JT, Albano AM. Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: results from the CAMS trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(2):212–24. doi: 10.1037/a0035458. A recent analysis of clinical and demographic factors which are associated with differential response to psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic response in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gittelman-Klein R, Klein DF. Controlled imipramine treatment of social phobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(3):204–207. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Klein RG, Koplewicz HS, Kanner A. Imipramine treatment of children with separation anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):21–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bernstein GA, Borchardt CM, Perwien AR, Crosby RD, Kushner MG, Thuras PD, Last CG. Imipramine plus cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of school refusal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(3):276–83. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]