Abstract

Among myeloid immune receptors, C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) have a remarkable capacity to sense a variety of self and non-self ligands. The coupling of CLRs to different signal transduction modules is influenced not only by the receptor, but also by the nature, density and architecture of the ligand, which can affect the rate of receptor internalization and trafficking to diverse intracellular compartments. Understanding how the variety of self and non-self ligands triggers differential CLR signalling and function presents a fascinating biological challenge. Non-self ligands usually promote inflammation and immunity, whereas self ligands are frequently involved in communication and tolerance. But pathogens can mimic self-inhibitory signals to escape immune surveillance, and endogenous ligands can contribute to the sensing of pathogens through CLRs. In this review, we survey the complexity and flexibility in functional outcome found in the myeloid CLRs, which is not only based on their differing intracellular motifs, but is also conditioned by the physical nature, affinity and avidity of the ligand.

Keywords: Innate immunity, C-type lectin receptors, Myeloid cells

Introduction: the C-type lectin domain is a flexible module for endogenous and exogenous ligands

The C-type lectin-like domain (CTLD) (Drickamer, 1999) is a structural motif composed of two loops with conserved cysteines that stabilize the structure with intra-chain disulphide bridges. The CTLD was initially defined functionally by its ability to bind carbohydrates in a calcium-dependent manner; however, the conserved structural module is also capable of calcium-dependent binding of glycans, lipids and proteins (Zelensky and Gready, 2005). This review focuses on integral membrane CLRs expressed on myeloid cells that modulate functional outcomes (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012).

CLRs are frequently promiscuous receptors that can bind more than one ligand. Myeloid CLRs can act as receptors for endogenous (self) or exogenous (non-self) ligands. Endogenous ligands can be further subdivided into self ligands involved in cell adhesion and communication and those regulating immune homeostasis (García-Vallejo and van Kooyk, 2009) or alternatively can be defined as “altered-self” neoglycans expressed by transformed cells (van Vliet et al., 2008) or “damaged self” danger signals released or exposed upon cell death (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2013).

The CLR DC-SIGN (CD209) illustrates the diversity of self and non-self ligands. DC-SIGN binds high-mannose and fucose-based ligands (LeX, LeY, LeA, LeB) that can be exposed on a variety of self receptors, such as ICAM-2, ICAM-3, CEACAM-1, Mac1 and CEA, or on non-self proteins such as Salp15 in the saliva of Ixodes, Arah1 in Schistosoma egg antigen, or structures in pathogens including viruses, bacteria, fungi and eukaryotic parasites (Geijtenbeek et al., 2000; Geijtenbeek et al., 2003; Gringhuis et al., 2009b; Hovius et al., 2008). The CLR Mincle (CLEC4E) can also bind non-self glycolipids in the cell wall of bacteria and fungi, while detecting self-damage by recognizing SAP-130 exposed and released by necrotic cells (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Schoenen et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2008; Yamasaki et al., 2009) (Ishikawa et al., 2013). Other CLRs detect one ligand that can be expressed in a variety of organisms, as described for Dectin-1 (CLEC7A), which detects β-1, 3 glucans in a variety of bacteria and fungi (Brown, 2006). Some CLRs appear to be restricted to endogenous ligands; for example, DNGR-1 (CLEC9A) detects filamentous F-actin exposed upon necrosis (Ahrens et al., 2012; Sancho et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012) and Clec12a senses uric acid crystals formed during cell death (Neumann et al., 2014).

The spectrum of CLR ligands and the structures bearing them is continually expanding and the general view is that most CLRs are adaptable structures that can bind both endogenous and exogenous ligands, resulting in distinct functional outcomes. The diversity of signalling pathways that can be triggered through CLRs depends initially on the cytoplasmic signalling motif, and we proposed a functional classification of signalling CLRs based on these motifs rather than the structure of the CTLD (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012). However, a single receptor can also signal differentially depending on the nature of the ligand; whether the ligand is of low or high affinity, soluble or particulate, or even its particle size will determine the strength and duration of signalling and the functional response. Ligand recognition and signal transduction through the CLR have a major impact on how self and non-self structures modulate myeloid cell function because CLRs work in concert with other innate receptors to control immunity and homeostasis. In this review we examine how the nature of the CLR motif and the bound ligand influence differential signal transduction.

Do myeloid CLRs transduce an activating or inhibitory signal?

Signalling myeloid CLRs can potentially trigger activating or inhibitory signals, depending on their cytoplasmic signalling motifs (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012). Some myeloid CLRs bear a hemITAM structure in their cytoplasmic domain, with a single tyrosine within an YXXL motif that couples to Syk (Rogers et al., 2005). Dectin-1, CLEC-2, DNGR-1 and SIGN-R3 belong to this group (Fuller et al., 2007; Huysamen et al., 2008; Rogers et al., 2005; Sancho et al., 2009; Tanne et al., 2009). Dectin-1 behaves as an activating CLR that promotes inflammation and immunity in response to pathogens such as Candida. CLEC-2 behaves as an activating receptor in platelets (Fuller et al., 2007) and myeloid cells (Mourao-Sa et al., 2011). SIGN-R3 couples to Syk and signals as an activating receptor (Tanne et al., 2009).

Despite sharing a common hemITAM motif, not all of these CLRs trigger the same transcriptional program; for example, they might be non-activating in some instances and depending on the context can even trigger inhibitory signals. In a macrophage cell line exposed to zymosan, a chimeric receptor consisting of the extracellular Dectin-1 and intracellular CLEC-2 structures induced Syk-dependent TNF production but not ROS (Kerrigan et al., 2009). SIGN-R3 can modulate signals by other CLRs (Lefèvre et al., 2013). In another study, the intracellular DNGR-1 structure was unable to mediate production of proinflammatory cytokines via the extracellular Dectin-1 domain by dendritic cells (DCs) (Zelenay et al., 2012). The inability of DNGR-1 to act as a myeloid activating receptor is strongly dependent on the presence of an isoleucine at position -1 relative to the tyrosine of the YXXL motif, and mutation of this isoleucine to glycine in the Dectin-1–DNGR-1 chimera results in increased cytokine production (Zelenay et al., 2012). The function of the hemITAM is defined by its binding to Syk, but the affinity for this binding can be regulated by the particular environment of the YXXL motif. In this regard, the DEDG motif that precedes the YXXL sequence in both Dectin-1 and CLEC-2 might be associated with enhanced association and signalling via Syk (Fuller et al., 2007). Thus not only the presence of the hemITAM but also the particular amino-acid environment around the tyrosine appear to influence the binding of Syk and the subsequent triggering of activating signals downstream of hemITAM-coupled CLRs.

A second group of myeloid CLRs couples to ITAM-bearing domains. MDL-1 (CLEC5A) couples to DAP-12 or DAP-10, which bear ITAM and YINM motifs, respectively (Bakker et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2008; Inui et al., 2009). BDCA-2, DCAR, Mincle and Dectin-2 couple to the FcRγ chain, which bears an ITAM motif that recruits Syk and mediates CARD9-dependent activation of NF-κB (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012). MCL couples to FcRγ (Miyake et al., 2013), an association that might be mediated by heterodimerization with Mincle (Lobato-Pascual et al., 2013). Although these receptors are considered to be activating, Syk recruitment to ITAM domains can also result in negative signals and inhibition of heterologous receptors. High avidity ligation of ITAM-coupled FcγRs in macrophages triggers a Syk-mediated induction of signalling inhibitors that abrogates TLR responses (Wang et al., 2010). Syk can also inhibit TLR signalling by inducing tyrosine phosphorylation of MyD88 and TRIF, leading to degradation of these adaptor molecules by the ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b (Han et al., 2010). Moreover, Mincle was recently shown to interfere with signalling via Dectin-1 despite both receptors signalling via Syk (Wevers et al., 2014), as we describe below.

Other myeloid CLRs contain ITIM motifs that recruit phosphatases that mediate negative regulation of kinase-associated heterologous receptors, for example the Syk-coupled CLRs. Co-ligation of these receptors with activating receptors results in modulation of the response, and these CLRs are thus candidate pathogen targets for immune escape. Myeloid CLRs included in this group are hDCIR, mDcir1 (DCIR), mDcir2, Clec12a (MICL, DCAL-2, KLRL1, CLL1), MAgH, and Ly49Q (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012). Finally, members of another class of myeloid CLRs do not bear evident ITAM or ITIM domains; these CLRs include MR, DEC-205, DC-SIGN, SIGNR1, Langerin, MGL, CLEC-1, DCAL-1, LOX-1 and LSECtin. DC-SIGN is the archetypal receptor of this group and its triggering results in modulation of signalling by heterologous receptors (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012).

An additional source of complexity in signal transduction through myeloid CLRs is their capacity to form dimers or multimers. Modelling of CLEC-2 signalling through hemITAMs indicates that Syk binding requires phosphorylation of paired YXXL motif tyrosines in a homodimer. Stoichiometric analyses show that CLEC-2 preexists as a dimer which then aggregates after ligand binding (Hughes et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2009). Some CLRs can also heterodimerize; for example, MCL forms a functional heteromeric complex with Mincle and FcRγ (Lobato-Pascual et al., 2013). Through this interaction, MCL acquires signalling capacity via FcRγ, whereas Mincle benefits from the endocytic capacity of MCL. Formation of the heterodimer could also potentially increase ligand-binding affinity or expand ligand specificity (Yamasaki, 2013).

The nature of the ligand can modulate signals through myeloid CLRs

In addition to the signalling motifs borne by the CLRs, signalling can also be influenced by the nature of the ligand, which can alter receptor engagement or induce conformational changes. CLRs frequently bind more than one ligand, each with a distinct affinity and avidity for the receptor. The importance of the nature of the ligand is well illustrated by signalling through DC-SIGN. Following binding of mannosylated lipoarabinomannan from M. tuberculosis, DC-SIGN couples to a LSP1-KSR1-CNK signalosome, leading to activation of Raf-1 and acetylation of the NF-κB p65 subunit, which results in enhanced pro-inflammatory responses (Gringhuis et al., 2009a). High mannose ligands from Candida or HIV-1 behave similarly and induce Raf-1 activation, whereas fucose-based ligands cause dissociation of the LSP1-based signalosome, so that DC-SIGN associates only with LSP1 and proinflammatory responses are suppressed (Gringhuis et al., 2009a). Salp15, a protein produced by the salivary glands of Ixodes scapularis ticks, also binds DC-SIGN to promote Raf-1 activation, in this case leading to MEK activation and suppression of inflammation (Hovius et al., 2008).

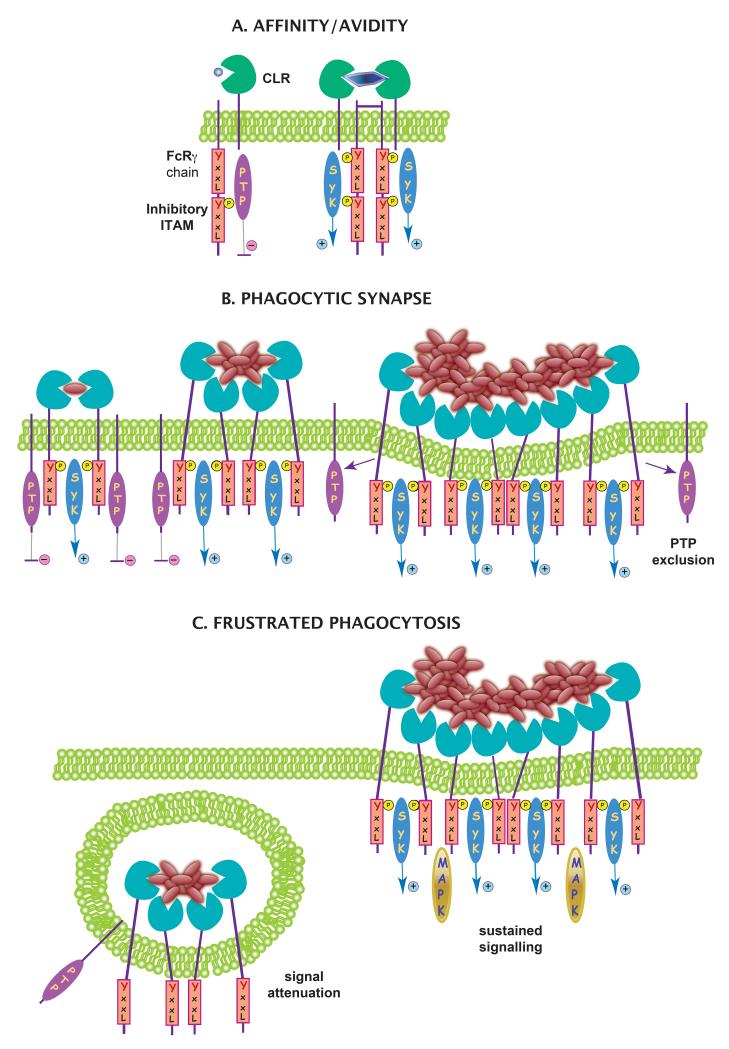

Ligand affinity and avidity can affect the quantity and duration of signals through the ITAM domain, resulting in differential responses (Hamerman et al., 2009; Yamasaki et al., 2004)(Fig. 1A). The FcRγ chain contains a consensus ITAM with two tyrosines that upon binding of a high-avidity ligand becomes fully phosphorylated and associates with the kinase Syk triggering an activating signal that contributes to immunity and inflammation (Mócsai et al., 2010). However, when ITAM-coupled receptors associate with low affinity or avidity ligands, the ITAM domain is hypophosphorylated and this results in preferential association with SH2-containing phosphatases, a configuration termed inhibitory ITAM (Blank et al., 2009). The paradigm of the differential effect of low affinity and avidity is the FcαRI receptor, which associates with the FcRγ chain for signalling. Upon interaction with IgA monomers, the coupled FcRγ chain is partially phosphorylated and recruits SHP-1 phosphatase, being able to inhibit signals through heterologous receptors (Pasquier et al., 2005). Some CLRs that couple to the FcRγ chain, including Mincle, Dectin-2, BDCA-2, DCAR or MCL, could thus potentially act in a similar manner to the FcαRI receptor and trigger phosphatase signalling upon binding to a low affinity/avidity ligand, which would lead to inhibition of signals triggered through heterologous receptors that could themselves be CLRs signalling via Syk. In this way, ITAM-associated CLRs could respond to low-valency ligation by soluble extracellular ligands that would induce broad suppression and dampening of inflammation and immunity. This recognition of low affinity/avidity ligands by ITAM-coupled receptors would thus act similarly to ITIM-coupled CLRs, which trigger a negative signal upon co-ligation with heterologous receptors by multivalent ligands, selectively regulating the co-ligated receptor (Hamerman et al., 2009).

Figure 1. The nature of the ligand can modulate signalling through myeloid CLRs.

Signalling myeloid CLRs can potentially trigger activating or inhibitory signals depending on their cytoplasmic signalling motifs and the nature of their ligands. (A) Affinity and avidity of the ligand can affect the quantity and duration of signals through the ITAM domain. Low affinity/avidity ligands induce hypo-phosphorylation of the ITAM domain in the FcRγ chain associated with the CLR. The hypophosphorylated ITAM, termed “inhibitory ITAM”, preferentially binds SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). Upon binding of a high avidity ligand, the FcRγ chain ITAM becomes fully phosphorylated and associates with Syk kinase, which triggers an activating signal. (B) Soluble and particulate ligands are differentially sensed by CLRs. Soluble ligands for CLR are poor triggers of activating signalling because of the inhibitory activity of membrane PTPs. When a phagocytic synapse is formed following binding of particulate ligands, these phosphatases are segregated from the receptors. (C) CLR signalling is influenced by the size of the ligand-bearing particle. Small particles are endocytosed, resulting in attenuation of signalling. Delayed or “frustrated” phagocytosis of large particles enhances signalling and inflammatory responses.

Affinity is also influenced by whether the ligand exists in a monomeric or oligomeric state, which affects how the ligand is presented to the CLR (Fig. 1B). Soluble ligands for CLRs are poor triggers of activating signalling, whereas the same ligands in plated form promote Syk signalling effectively. This might provide a mechanism to restrict activation of the tightly regulated processes of phagocytosis and ROS production to situations when the host is in direct contact with pathogen. In this regard, Dectin-1 has been proposed to cluster in a “phagocytic synapse” only when it interacts directly with particulate, but not soluble, β-glucans (Goodridge et al., 2011). CD45 and CD148 phosphatases are initially needed for dephosphorylation of the Src family kinase Lyn at its inhibitory tyrosine (Y507), but are subsequently excluded from the β-glucan particle contact site to permit Syk association and signalling (Goodridge et al., 2011). This formation of a phagocytic synapse that excludes membrane phosphatases may be a general feature of other phagocytic CLRs, which would thus discriminate between detection of soluble and particulate ligands (Fig. 1C). After detection of soluble ligands, the inhibitory activity of membrane tyrosine phosphatases would not be segregated from the receptors, and CLR signalling would be attenuated. As mentioned above, non-receptor phosphatases such as SHP-1 could also dampen CLR signalling and, depending on ligand affinity, compete with Syk for binding to the phosphorylated tyrosine.

CLR signalling is also influenced by the size of the particle on which the ligand is expressed. Presentation of CLR ligands on large particles rather than in solution or even on small particles could promote delayed or “frustrated” phagocytosis, which results in an enhanced cytokine response (Hernanz-Falcón et al., 2009; Rosas et al., 2008) (Fig. 1C). Large aggregates of microparticulate β-glucan, known as Curdlan particles, are much more potent than non-aggregated β-glucan microparticules at inducing signalling and inflammatory responses via Dectin-1 expressed on DCs or macrophages (Rosas et al., 2008). The poor ability of β-glucan microparticles to trigger potent IL-6 or TNF production via Dectin-1 can be reverted by the actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D, which blocks phagocytosis of the microparticles and thus promotes inflammatory signals (Rosas et al., 2008). Blockade of ligand-driven internalization of Dectin-1, either with large β-glucan particles or with inhibitors of actin polymerization or dynamin, results in sustained MAPK activation (Hernanz-Falcón et al., 2009), suggesting that endocytosis of the receptor leads to attenuation of inflammatory responses. This attenuation could be mediated by disassembly of signalling complexes upon receptor internalization or by improved access of inhibitory factors (e.g. phosphatases) to the signalling complex. Other Syk-dependent signals, however, such as ROS production, appear to be regulated differently since they are active upon receptor internalization (Underhill et al., 2005). Plated ligands probably mimic this “frustrated” phagocytosis, resulting in exaggerated signalling.

Sensing of self and non-self by myeloid CLRs: plasticity of functional outcomes

We describe above how the complexity of signalling motifs and ligand interaction with myeloid CLRs results in distinct functional outcomes. In this section, we illustrate how self and non-self ligands target CLRs. We present examples of how myeloid CLRs detect self for homeostasis or promotion of tolerance, whereas detection of damaged-self contributes to immunity. When detecting non-self, myeloid CLRs also act as innate receptors that trigger immunity and inflammation. However, in certain circumstances pathogens exploit the versatility of CLRs for immune evasion.

Sensing non-self to favour immunity and inflammation

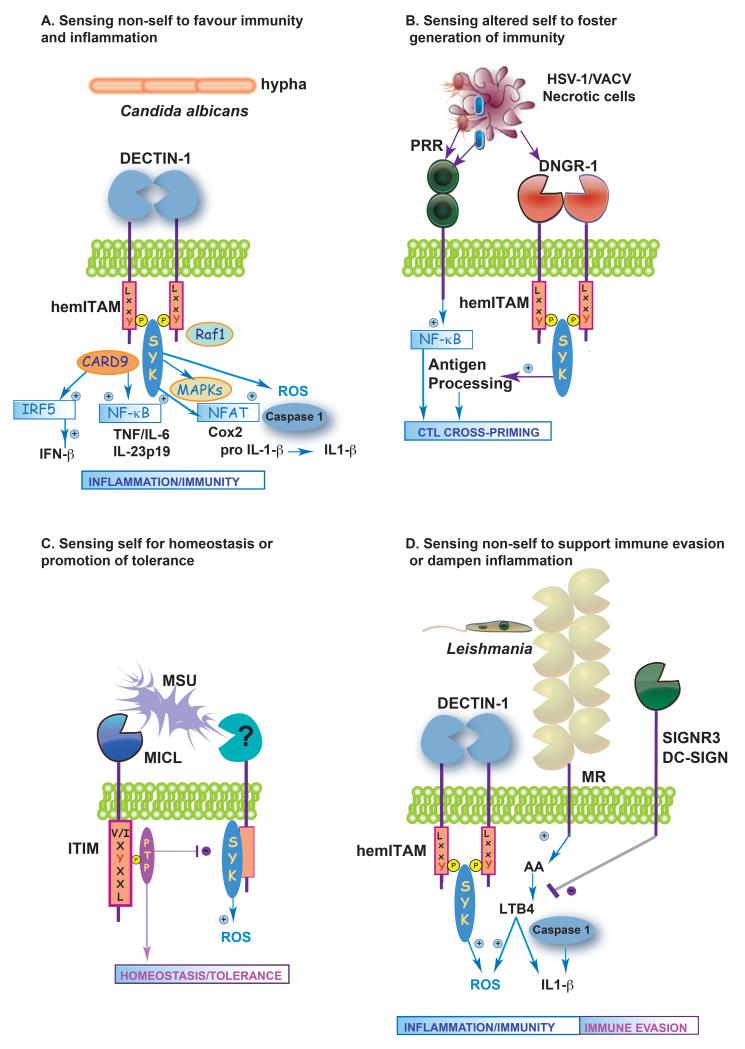

The immune system has evolved to protect the host from infection. Charles Janeway hypothesized the existence of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) as sensors of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and inducers of the co-stimulatory capacity of DCs (Janeway, 1989). The induction of a signalling pathway by these PRRs leads to innate cell activation, which in turn orchestrates an appropriate inflammatory response and instructs the nature of the adaptive response. Most pathogen-detecting CLRs are phagocytic or scavenger-type receptors, and as such contribute to an immune response but are not primary drivers. The archetypal example of a myeloid CLR able to initiate immunity is Dectin-1, which recognizes β-glucans present in the cell wall of many fungi (Brown, 2006)(Fig. 2A). The phosphorylated tyrosine in the hemITAM recruits Syk kinase, which in turn activates the CARD9/Bcl10/Malt-1 module that activates the IκB kinase (IKK) complex to induce canonical NF-κB signalling (Gross et al., 2006). Syk can also activate MAPK (Leibundgut-Landmann et al., 2007; Slack et al., 2007) and NFAT (Goodridge et al., 2007), which collaborate with NF-κB in the activation of a transcriptional programme. Human Dectin-1 also induces a Syk-independent pathway mediated by the serine/threonine protein kinase Raf-1, which results in acetylation of NF-κB and subsequent modulation of transcription (Gringhuis et al., 2009b). Activation of these signalling pathways induces transcription of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-6 and IL-23 and the regulatory cytokines IL-2 and IL-10 (Leibundgut-Landmann et al., 2007), a pattern somewhat different from the cytokines stimulated by TLRs. The specific Dectin-1 agonist Curdlan acts as an adjuvant to trigger an adaptive response in vitro and in vivo, leading to Th1 and Th17 type immunity (Leibundgut-Landmann et al., 2007). In addition, sensing of Candida albicans by Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 results in activation of IFN-β production through a Syk-IRF5 axis (del Fresno et al., 2013). Dectin-2 is the predominant Syk-coupled receptor in the response of DCs to C. albicans, and induction of Th17 immunity against the fungus in mouse models (Robinson et al., 2009; Saijo et al., 2010). Apart from inducing transcriptional responses, both Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 mediate Syk-dependent ROS generation (Gross et al., 2006; Ritter et al., 2010; Underhill et al., 2005) which has a direct microbicidal role and triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation and processing of pro-IL-1β to IL-1β essential for anti-fungal immunity (Gross et al., 2009).

Figure 2. Self and non-self sensing by myeloid CLRs: plasticity of functional outcomes.

The complexity of signalling motifs and ligand interaction with myeloid CLRs can result in distinct functional outcomes: (A) Sensing non-self to favour immunity and inflammation: Dectin-1 detects β-glucan carbohydrates on Candida albicans. After ligand binding, Dectin-1 can mediate multiple cellular responses in a Syk-dependent or independent (Raf1) manner, including cytokine and chemokine production, respiratory burst, phagocytosis and IFN-β production. (B) Sensing altered self to foster generation of immunity: Cells infected with cytophatic viruses (HSV-1 or VACV) can be detected by TLRs and DNGR-1 expressed on DCs. Whereas PRRs promote activation of the DCs, DNGR-1 favours CTL priming by sequestering cargo in a poorly degradative early endocytic compartment that allows MHC class I cross-presentation. (C) Sensing self for homeostasis or promotion of tolerance; Monosodium urate (MSU) is a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) that induces Syk-dependent ROS production. Clec12a can sense MSU and promote an inhibitory signal through its ITIM that dampens inflammation. (D) Sensing non-self to support immune evasion or dampen inflammation: During Leishmania infantum infection, Dectin-1 and MR induce ROS production in macrophages and trigger Syk-coupled secretion of IL-1β. SIGNR3 (DC-SIGN in human macrophages) promotes parasite survival by inhibiting the LTB4/IL-1β axis.

Sensing non-self to induce immunity and inflammation confers the host with an advantage in the fight against a pathogen, but is an undesired outcome when the non-self triggering agent is an allergen. Allergenic extracts from Aspergillus fumigatus or house-dust mites bind Dectin-2 and trigger Syk-dependent arachidonic acid metabolism and rapid production of cysteinyl leukotrienes (Barrett et al., 2009). These lipid mediators promote Th2 responses with increased eosinophilia and neutrophilia in the lung (Barrett et al., 2011). Another setting in which sensing non-self to promote inflammation can be deleterious to the host is during viral infections with severe immunopathology, for example sensing of Dengue virus by MDL-1 (CLEC5A), which results in phosphorylation of DAP12 ITAM and generation of a Syk-dependent proinflammatory response (Chen et al., 2008). Exaggerated inflammation results in a shock syndrome, with plasma leakage and subcutaneous and vital organ haemorrhaging. Blockade of the MDL-1-Dengue virus interaction in a mouse model suppresses the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages, preventing the excessive immunopathology (Chen et al., 2008).

Sensing self to foster generation of immunity

In addition to directly sensing pathogens, the immune system also responds to danger, as demonstrated by adaptive immune responses to damaged tissue or necrotic cells in apparently infection-free situations. The model of innate recognition of dangerous-self proposes that preformed endogenous adjuvants inside healthy cells, known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), are exposed or released upon necrotic cell death (Matzinger, 1994). The sensing of damaged cells by DCs has attracted much interest in understanding how these pathways might be exploited to improve vaccine design. The CLR DNGR-1 (CLEC9A) is selectively expressed on DC subsets specialized in cross-presentation of antigens from dead cells in mice and humans (Caminschi et al., 2008; Huysamen et al., 2008; Poulin et al., 2010; Sancho et al., 2008). DNGR1 recognizes F-actin complexed to the actin-binding domain of certain cytoskeletal molecules (Ahrens et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). To date, no other ligands for DNGR1 have been found in pathogens, although it has been found to bind fungal F-actin (Ahrens et al., 2012). It could be argued that DNGR1 is non-essential for immunity to pathogens. However, our work demonstrated that cells infected with vaccinia virus (VACV) eventually expose DNGR-1 ligands (Iborra et al., 2012)(Fig. 2B); while dispensable for activation of DCs, DNGR1 was crucial for cross-presentation of necrotic cargo associated with VACV or herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)-infected cells (Iborra et al., 2012; Zelenay et al., 2012). DNGR-1 thus plays a non-redundant role in the cross-priming of CTLs in models of cytopathic infection with HSV-1 or VACV (Iborra et al., 2012; Zelenay et al., 2012). These results suggest that DNGR1 diverts necrotic cargo away from lysosomes, targeting them for accumulation in a pre-lysosomal compartment devoted to cross-presentation (Iborra et al., 2012; Zelenay et al., 2012). Sensing of damaged self during viral infection by DNGR1 favours antigen processing for cross-presentation and cooperates with PRRs that mediate activation of DCs to promote CTL immunity. Moreover, poxviruses and other intracellular pathogens are propelled beneath the plasma membrane into surrounding cells by growing actin tails (Welch and Way, 2013) that are brightly stained with the DNGR1 extracellular domain (Ahrens et al., 2012). Since these actin tails containing DNGR-1 ligand are exposed on damaged infected cells, one could hypothesize that DNGR1 has evolved during host-intracellular pathogen coevolution to detect this danger signal on infected cells and favour host responses. This interaction would allow non-infected healthy DCs to take up and process antigens that can then cross-prime CTL responses.

Sensing self for homeostasis or promotion of tolerance

In addition to the inflammation and immunity that can result from sensing of dangerous-self, self-sensing could also potentially lead to tolerance or prevention of immunopathology. It has been proposed the existence of “self-associated molecular patterns” (SAMPs), which would be recognized by intrinsic cognate inhibitory receptors Self-PRRs (SPRRs) in order to maintain the homeostatic non-activated state of innate immune cells and dampen their reactivity (Elward and Gasque, 2003; Varki, 2011). An example of these putative SAMPs is provided by sialic acid patterns, which are detected by SPRRs such as Siglecs (sialic acid recognizing Ig-like lectins). These SPRRs often have ITIM motifs within their cytosolic tails. Consistent with this idea, deletion of Siglec-F from mouse eosinophils produces a hyperactive response (Zhang et al., 2007), and mouse Siglec-G deletion results in over-reactive responses to DAMPs and PAMPs (Chen et al., 2009).

One putative SPRR among CLRs is DCIR. This receptor is expressed mainly on DCs and has an extracellular carbohydrate-recognition domain and an ITIM motif. Autoimmune-related genes map to the DCIR locus in humans, and aged DCIR-deficient mice spontaneously develop sialadenitis and enthesitis associated with elevated serum autoantibodies. These mice also showed a markedly exacerbated response to collagen-induced arthritis. Thus, DCIR behaves as a SPRR, recognizing a self-associated-pattern and maintaining immune system homeostasis (Fujikado et al., 2008). Notably, DCIR can be targeted by intravenous immunoglobulins expressing sialic acid and mediates a negative signal in DCs via SHP-2 and SHIP-1, resulting in the generation of Tregs and attenuation of allergic airway disease (Massoud et al., 2014).

Clec12a was recently identified as another CLR that mediates an anti-inflammatory response through recognizing a well-established DAMP, uric acid (Neumann et al., 2014)(Fig. 2C). Uric acid is soluble in healthy cells, but forms monosodium urate (MSU) crystals when it comes into contact with extracellular sodium ions upon cell death. MSU activates Syk signalling in myeloid cells through direct interaction with the membrane or through unidentified mechanisms involving CD16 and CD11b (Barabe et al., 1998; Desaulniers et al., 2001; Ng et al., 2008). Human and mouse Clec12a both sense MSU (Neumann et al., 2014), although it is not fully understood how this recognition works. MSU induces Syk-dependent production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and Clec12a inhibits this production in neutrophils (Neumann et al., 2014). Injection of MSU crystals into the peritoneum of mice induces neutrophil infiltration that is augmented in Clec12a-deficient mice. Notably, Clec12a does not affect ROS production induced by Dectin-1, suggesting that, to induce its inhibitory effects, Clec12a requires coengagement with the activating receptor for MSU. Because Clec12a includes an ITIM within its cytoplasmic tail, its negative regulatory role is likely to be mediated by recruited phosphatases.

Sensing non-self to support immune evasion or dampen inflammation

The proposal that SAMPs dampen inflammation in response to self antigens opens up a possible route for pathogens to mimic SAMPs for their own benefit. For example, the Trypanosoma cruzi cell surface contains sialoglycoproteins and sialyl-binding proteins that assist the parasite in several functions including parasite survival, infectivity, and host–cell recognition, and could act as SAMPs (Freire-de-Lima et al., 2012). ITIM-coupled CLRs such as DCIR could behave as SPRRs that are targeted directly or indirectly (e.g. by tissue damage) by pathogens to dampen immunity and inflammation. In this regard, DCIR-deficient mice (Clec4a2−/−) exhibit severe inflammatory disease upon Chikungunya virus infection (Long et al., 2013). Early differences in virus-induced disease between DCIR-deficient and wild-type mice are independent of viral replication, and there is no evidence for direct interactions between DCIR and Chikungunya virus, suggesting that DCIR might sense the pathogen indirectly and contribute to increased tolerance of pathogen-induced damage by dampening immunopathology and reducing the negative impact of the pathogen on host fitness (Medzhitov et al., 2012). Conversely, in a model of cerebral malaria caused by Plasmodium berghei, DCIR-deficient mice are more resistant, correlating with reduced T-cell priming in the spleen, decreased TNF levels in the serum, and diminished T-cell retention in the brain (Maglinao et al., 2013). No evidence was found for direct binding of DCIR to P. berghei, suggesting that DCIR recognizes a self-DAMP released by the rupture of red blood cells during infection. These studies highlight the potential plasticity of DCIR depending on the ligand and the inflammatory context.

As discussed above, inhibitory signals can also be mediated by ITAM-coupled receptors. The ITAM-coupled CLR Mincle, in addition to sensing SAP-130—a self-ligand released by necrotic cells (Yamasaki et al., 2008)—binds glycolipids in the cell walls of fungi and bacteria (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Ishikawa et al., 2013; Schoenen et al., 2010; Sousa et al., 2011; Yamasaki et al., 2009). Mincle is an activating receptor that upon ligand recognition triggers a strong Syk-dependent inflammatory response and robust Th1 and Th17 immunity (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Ishikawa et al., 2013; Schoenen et al., 2010; Shenderov et al., 2013; Sousa et al., 2011; Wells et al., 2008; Yamasaki et al., 2009). However, in certain conditions Mincle can deliver a negative signal to heterologous receptors. Mincle and Dectin-1 recognize Fonsecaea monophora, a cause of chromoblastomycosis. Stimulation of human DCs with F. monophora triggers the maturation of DCs and production of IL-6, IL-1β and IL-23, but not IL-12p70. While Dectin-1 acts as a PRR, promoting Syk-dependent cytokine production, stimulation of Syk by Mincle triggers a PKB-dependent signal that leads to loss of IRF1 activity (Wevers et al., 2014). Notably, Mincle suppresses TLR-4–induced IL-12p70 expression by inhibiting IL-12p35 transcription (Wevers et al., 2014). These findings suggest that Mincle can support or inhibit immunity depending on the nature of the ligand, thus modulating the response of heterologous receptors for the same pathogen. Mincle is also involved in innate sensing of F. pedrosoi in mice, but this recognition does not seem to be efficient enough to promote protective immunity against the fungus, instead leading to chronic infection (Sousa et al., 2011). Intriguingly, when mice are treated with TLR agonists, TLR signalling cooperates with Mincle in the generation of a potent inflammatory response that resolves the disease (Sousa et al., 2011). The reasons for this apparent discrepancy between humans and mice are unknown, but it could imply the existence of additional receptors that heterodimerize with Mincle in mouse, as described for MCL (Miyake et al., 2013), or of different transduction modules associated with human monocyte-derived DCs compared with mouse bone marrow-derived DCs. In this regard, the ability of a given CLR to drive NF-κB activation is myeloid-cell-type dependent. DCs derived from bone marrow progenitors and differentiated in vitro with GM-CSF are easily activated by Dectin-1 agonists, whereas Flt3L-derived bone marrow DCs and M-CSF-derived macrophages are poor NF-κB activators (Goodridge et al., 2009). This difference might be explained by the expression levels of CARD9 or other key limiting signalling proteins. Thus, depending on the cellular context, the simultaneous engagement of CLRs and TLRs could lead to cooperation or antagonism.

DC-SIGN recognizes endogenous glycoproteins and also interacts with a wide range of pathogens through the recognition of mannose and fucose, but its contribution to host defence is still debated. DC-SIGN can contribute to adaptive immunity by targeting antigens to late endosomal/lysosomal compartments for degradation and presentation to T cells. But DC-SIGN also induces signals that promote HIV-1 replication in DCs and transmission to T cells (Hodges et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2002). Similarly, the interaction of M. tuberculosis with DC-SIGN suggests that the pathogen has evolved to exploit the receptor as part of an immunoevasive strategy involving the secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 from DCs (Geijtenbeek et al., 2003). Mannose-containing M. tuberculosis and HIV-1 induce the recruitment of the LSP1 signalosome described above, which activates Raf-1 and modulates TLR signalling (Gringhuis et al., 2007; Gringhuis et al., 2009a). The DCs of transgenic mice expressing human DC-SIGN under the control of the mouse CD11c promoter (termed hSIGN) produce significantly less IL-12p40 than wild-type counterparts and similar amounts of IL-10. After infection with M. tuberculosis, hSIGN mice show massive accumulation of DC-SIGN+ cells in infected lungs, below-normal tissue damage and prolonged survival. These results suggest that, rather than promoting immune evasion by mycobacteria, human DC-SIGN may have evolved to limit tuberculosis-induced pathology (Schaefer et al., 2008). Similarly, the DC-SIGN mouse homolog SIGNR3 dampens inflammation mediated by other CLRs that sense Leishmania infection (Lefèvre et al., 2013) (Fig. 2D). Macrophages act as the main host and primary effector cells during Leishmania infection. The macrophage response to Leishmania infantum in vivo is characterized by M2b polarization (Mantovani et al., 2004) and is detected by Dectin-1, mannose receptor (MR), and SIGNR3. Dectin-1 and MR respectively activate Syk-p47phox and arachidonic acid-NADPH oxidase signalling pathways, both of which are needed for ROS production, and also trigger Syk-coupled signalling for caspase-1-induced IL-1β secretion. Dectin-1 and MR thus contribute to parasite containment, whereas SIGNR3 favours parasite resilience through inhibition of the LTB4-IL-1β axis.

Concluding remarks

Myeloid CLRs detect self and non-self to mediate multiple roles. The outcome of myeloid CLR interaction with a ligand depends critically on the signals triggered, which are conditioned by the signalling motifs. The classical view of activating ITAMs and inhibitory ITIMs is complicated by the ability of low ligand density to lead to inhibitory ITAM signalling. Additionally, under certain circumstances Syk-dependent responses can also lead to inhibition of gene transcription. Soluble ligands also result in weaker signalling than particulate ligands, which form a synapse that excludes inhibitory phosphatases. In addition, large particles that frustrate phagocytosis can signal for longer than small particles, whose signal is attenuated by endocytosis.

This complex and versatile regulation of functional responses depends on the ligand and the signalling motifs present in the receptor and leads to a great variety of responses to self and non-self antigens. Myeloid CLRs mediate immunity and inflammation against non-self, in collaboration with the detection of dangerous-self signals. However, CLRs can also be targeted by pathogens and self-ligands to dampen inflammation and immunity. These functions might have been selected in evolution to reduce immunopathology by increasing host tolerance of pathogen-induced damage, providing an alternative strategy to reducing the negative impact of the pathogen on host fitness. Further research is needed to clarify the contribution of ligands and signalling motifs to the functional outcomes of signalling through myeloid CLRs, with the aim of identifying novel targets for improving immunity against pathogen or, conversely, reducing the immunopathology associated with infection.

Table 1.

Mouse and human myeloid CLRs surveyed in this review.

| Common name(s) | Gene name | Signaling motifs | Early signaling effectors | Ligand specificity | Ligand origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-SIGN, CLEC4L (Hs) | CD209 (Hs) | YxxL LL EEE |

ManLAM: LSP1, KSR1, CNK RAF-1 Salp15: MEK-RAF-1 Fucose: LSP1 |

High mannose and fucose (LeX, LeY, LeA, LeB) | - HIV-1, measles, Dengue, SARS, CMV, filoviruses - Mycobacterium spp., Lactobacilli spp., H. pylori, E. coli - C. albicans - Leishmania spp. - Ixodes saliva Salp15, Schistosoma egg antigen, Arah1 - ICAM-2, ICAM-3, CEACAM-1, Mac1, CEA |

| SIGNR3 (Mm) | Cd209d (Mm) | YxxI | HemITAM-SYK | High mannose and fucose | - M. tuberculosis |

| BDCA-2, DLEC, CD303, CLECSF7 (Hs) | CLEC4C (Hs) | Tmb K EEE |

FcRγ chain-ITAM-SYK | gp120 | HIV-1 |

| DCAR (Mm) | Clec4b1 (Mm) | Tmb R | FcRγ chain-ITAM-SYK | ND | ND |

| mDCAR1 (Mm) | Clec4b2 (Mm) | Tmb R | FcRγ chain-ITAM-SYK? | ND | ND |

| DCIR, CLECS-F6, LLIR (Hs) | CLEC4A (Hs) | IxYxxV | SHP-1, SHP-2 | ND | HIV-1 |

| DCIR, Dcir1, Clecf6 (Mm) | Clec4a2 (Mm) | IxYxxV | SHP-1, SHP-2 | Syalilated glicoproteins | - Syalilated intravenous inmunoglobulins |

| Dcir2 (33D1) (Mm) | Clec4a4 (Mm) | IxYxxV | ND | ND | ND |

| Dectin-2 | CLEC6A (Hs) Clec4n (Mm) |

Tmb R | FcRγ chain-ITAM-SYK Src kinases CARD9 |

High mannose α-mannans | - M. tuberculosis - A. fumigatus, C. albicans, S. cerevisiae, P. brasiliensis, H. capsulatum, M. audouinii, T. rubrum, C. neoformans - house dust mite allergens, S. mansoni eggs extracts - Ligand on CD4+ CD25+ T cells |

| MCL, CLECS-F8 | CLEC4D (Hs) Clec4d (Mm) |

ND | FcRγ chain through Mincle heterodimer |

glycolipids | - M. tuberculosis |

| Mincle | CLEC4E (Hs) Clec4e (Mm) |

Tmb R | FcRγ chain-ITAM-SYK Src kinases CARD9 |

glycolipids, SAP-130. | - M. tuberculosis - C. albicans, Malassezia spp, Fonsecaea pedrosoi. - dead cells |

| MDL-1, CLECSF5 | CLEC5A (Hs) Clec5a (Mm) |

Tmb K | DAP10 - PI3K DAP12-ITAM-SYK |

ND | - Dengue virus - Role in osteoclastogenesis: endogenous ligand? |

| CLEC12A, MICL, DCAL-2, KLRL1, CLL1 | CLEC12A (Hs) Clec12a (Mm) |

VxYxxL | SHP-1, SHP-2 | monosodiumurate crystals | - dead cells. |

| CLEC-2 | CLEC1B (Hs) Clec1b (Mm) |

YxxL DEDG LL |

HemITAM-SYK; Src and Tec kinases. |

-Podoplanin - rhodocytin |

- lymphatic endothelial cells, lymph node stroma, tumor cells, HIV-1 - snake venom |

| DNGR-1, CLEC9A | CLEC9A (Hs) Clec9a (Mm) |

YxxL | HemITAM-SYK | F-actin | - dead cells |

| Dectin-1, β-GR, CLECSF12 | CLEC7A (Hs) Clec7a (Mm) |

YxxL DEDG |

HemITAM-SYK CARD9 RAF-1 |

β-1,3 glucans | - Mycobacteria spp. - P. carinii, C. albicans, A. fumigatus, Penicillium marneffei, Coccidioides posadasii, and Histoplasma capsulatum - Ligand on T cells |

| MR, MMR, CD206 | MRC1 (Hs) Mrc1 (Mm) |

FxxxxY LL |

CDC42, RHOB, PAKs, ROCK1 | High mannose, Fucose, sLeX, GlcNAc | - HIV-1, Dengue - M. tuberculosis, M. kansasii, F. tularensis, K. pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae - P. carinii, C. albicans, C. neoformans - Leishmania spp. -glycosylated allergens - Lysosomal hydrolases, thyroglobulin, L-selectin, MUC-1, apoptotic cells |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the Immunobiology of Inflammation laboratory for helpful discussion. We thank Simon Bartlett (CNIC) for editorial assistance. Work in the Immunobiology of Inflammation laboratory is funded by the CNIC and grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (SAF-2010-15120) and the European Research Council (ERC Starting Independent Researcher Grant 2010, ERC-2010-StG 260414). DS is the recipient of a Ramón y Cajal fellowship (RYC-2009-04235) from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

Abbreviations

- BDCA

Blood DC antigen

- CEACAM

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule

- CLR

C-type lectin receptor

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- CTLD

C-type lectin domain

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- DC

dendritic cell

- cDC

conventional DC

- dDC

dermal DC

- DC-SIGN

dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin

- DCAR

DC activating receptor

- DCIR

DC inhibitory receptor

- Dectin

DC-associated C-type lectin

- dLN

draining lymph node

- DNGR-1

dendritic cell NK lectin group receptor 1

- i.d.

intradermal

- ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- ITIM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCL

macrophage C-type lectin

- MDL

Myeloid DAP-12 associated lectin

- Mincle

macrophage-inducible C-type lectin

- MR

Mannose Receptor

- MSU

Monosodium urate

- p.i.

post-infection

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SHP-1

Src homology 2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-1

- SIGN-R3

specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing non-integrin homolog-related 3

- Syk

spleen tyrosine kinase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure.

The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- Ahrens S, Zelenay S, Sancho D, Hanč P, Kjær S, Feest C, Fletcher G, Durkin C, Postigo A, Skehel M, et al. F-Actin Is an Evolutionarily Conserved Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern Recognized by DNGR-1, a Receptor for Dead Cells. Immunity. 2012;36:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Myeloid DAP12-associating lectin (MDL)-1 is a cell surface receptor involved in the activation of myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9792–9796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabe F, Gilbert C, Liao N, Bourgoin SG, Naccache PH. Crystal-induced neutrophil activation VI. Involvment of FcgammaRIIIB (CD16) and CD11b in response to inflammatory microcrystals. FASEB J. 1998;12:209–220. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett NA, Maekawa A, Rahman OM, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y. Dectin-2 recognition of house dust mite triggers cysteinyl leukotriene generation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1119–1128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett NA, Rahman OM, Fernandez JM, Parsons MW, Xing W, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y. Dectin-2 mediates Th2 immunity through the generation of cysteinyl leukotrienes. J Exp Med. 2011;208:593–604. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank U, Launay P, Benhamou M, Monteiro RC. Inhibitory ITAMs as novel regulators of immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;232:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD. Dectin-1: a signalling non-TLR pattern-recognition receptor. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:33–43. doi: 10.1038/nri1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminschi Proietto, Ahmet Kitsoulis, Teh Lo, Rizzitelli Wu, Vremec, Dommelen v., et al. The dendritic cell subtype restricted C-type lectin Clec9A is a target for vaccine enhancement. Blood. 2008;112:3264–3273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G-Y, Tang J, Zheng P, Liu Y. CD24 and Siglec-10 selectively repress tissue damage-induced immune responses. Science. 2009;323:1722–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1168988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S-T, Lin Y-L, Huang M-T, Wu M-F, Cheng S-C, Lei H-Y, Lee C-K, Chiou T-W, Wong C-H, Hsieh S-L. CLEC5A is critical for dengue-virus-induced lethal disease. Nature. 2008;453:672–676. doi: 10.1038/nature07013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Fresno C, Soulat D, Roth S, Blazek K, Udalova I, Sancho D, Ruland J, Ardavin C. Interferon-beta Production via Dectin-1-Syk-IRF5 Signaling in Dendritic Cells Is Crucial for Immunity to C. albicans. Immunity. 2013;38:1176–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaulniers P, Fernandes M, Gilbert C, Bourgoin SG, Naccache PH. Crystal-induced neutrophil activation. VII. Involvement of Syk in the responses to monosodium urate crystals. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:659–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drickamer K. C-type lectin-like domains. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 1999;9:585–590. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elward K, Gasque P. “Eat me” and “don’t eat me” signals govern the innate immune response and tissue repair in the CNS: emphasis on the critical role of the complement system. Mol Immunol. 2003;40:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(03)00109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire-de-Lima L, Oliveira IA, Neves JL, Penha LL, Alisson-Silva F, Dias WB, Todeschini AR. Sialic acid: a sweet swing between mammalian host and Trypanosoma cruzi. Front Immunol. 2012;3:356. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikado Saijo, Yonezawa Shimamori, Ishii Sugai, Kotaki Sudo, Nose, Iwakura Dcir deficiency causes development of autoimmune diseases in mice due to excess expansion of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nm1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller GLJ, Williams JAE, Tomlinson MG, Eble JA, Hanna SL, Pöhlmann S, Suzuki-Inoue K, Ozaki Y, Watson SP, Pearce AC. The C-type lectin receptors CLEC-2 and Dectin-1, but not DC-SIGN, signal via a novel YXXL-dependent signaling cascade. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12397–12409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609558200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Vallejo JJ, van Kooyk Y. Endogenous ligands for C-type lectin receptors: the true regulators of immune homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2009;230:22–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TBH, van Vliet SJ, Koppel EA, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, Appelmelk B, van Kooyk Y. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:7–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge HS, Reyes CN, Becker CA, Katsumoto TR, Ma J, Wolf AJ, Bose N, Chan ASH, Magee AS, Danielson ME, et al. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature. 2011;472:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge HS, Shimada T, Wolf AJ, Hsu Y-MS, Becker CA, Lin X, Underhill DM. Differential use of CARD9 by Dectin-1 in macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1146–1154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge HS, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 stimulation by Candida albicans yeast or zymosan triggers NFAT activation in macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:3107–3115. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringhuis, Dunnen d., Litjens, Hof v.H., Kooyk v., Geijtenbeek C-Type Lectin DC-SIGN Modulates Toll-like Receptor Signaling via Raf-1 Kinase-Dependent Acetylation of Transcription Factor NF-kappaB. Immunity. 2007;26:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringhuis SI, Den Dunnen J, Litjens M, Van Der Vlist M, Geijtenbeek TBH. Carbohydrate-specific signaling through the DC-SIGN signalosome tailors immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, HIV-1 and Helicobacter pylori. Nat Immunol. 2009a;10:1081–1088. doi: 10.1038/ni.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringhuis SI, Den Dunnen J, Litjens M, Van Der Vlist M, Wevers B, Bruijns SCM, Geijtenbeek TBH. Dectin-1 directs T helper cell differentiation by controlling noncanonical NF-kappaB activation through Raf-1 and Syk. Nat Immunol. 2009b;10:203–213. doi: 10.1038/ni.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Gewies A, Finger K, Schäfer M, Sparwasser T, Peschel C, Förster I, Ruland J. Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature. 2006;442:651–656. doi: 10.1038/nature04926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschläger N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer Tybulewicz, et al. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature. 2009;459:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamerman JA, Ni M, Killebrew JR, Chu C-L, Lowell CA. The expanding roles of ITAM adapters FcRgamma and DAP12 in myeloid cells. Immunol Rev. 2009;232:42–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Jin J, Xu S, Liu H, Li N, Cao X. Integrin CD11b negatively regulates TLR-triggered inflammatory responses by activating Syk and promoting degradation of MyD88 and TRIF via Cbl-b. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:734–742. doi: 10.1038/ni.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernanz-Falcón P, Joffre O, Williams DL, Reis e Sousa C. Internalization of Dectin-1 terminates induction of inflammatory responses. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:507–513. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges A, Sharrocks K, Edelmann M, Baban D, Moris A, Schwartz O, Drakesmith H, Davies K, Kessler B, McMichael A, Simmons A. Activation of the lectin DC-SIGN induces an immature dendritic cell phenotype triggering Rho-GTPase activity required for HIV-1 replication. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ni1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovius JWR, de Jong MAWP, Dunnen J.d., Litjens M, Fikrig E, van der Poll T, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TBH. Salp15 binding to DC-SIGN inhibits cytokine expression by impairing both nucleosome remodeling and mRNA stabilization. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CE, Pollitt AY, Mori J, Eble JA, Tomlinson MG, Hartwig JH, O’Callaghan CA, Fütterer K, Watson SP. CLEC-2 activates Syk through dimerization. Blood. 2010;115:2947–2955. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huysamen C, Willment JA, Dennehy KM, Brown GD. CLEC9A is a novel activation C-type lectin-like receptor expressed on BDCA3+ dendritic cells and a subset of monocytes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16693–16701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709923200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iborra S, Izquierdo HM, Martinez-Lopez M, Blanco-Menendez N, Reis e Sousa C, Sancho D. The DC receptor DNGR-1 mediates cross-priming of CTLs during vaccinia virus infection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1628–1643. doi: 10.1172/JCI60660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui, Kikuchi Y, Aoki N, Endo S, Maeda T, Sugahara-Tobinai A, Fujimura S, Nakamura A, Kumanogoh A, Colonna M, Takai Signal adaptor DAP10 associates with MDL-1 and triggers osteoclastogenesis in cooperation with DAP12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4816–4821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900463106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa E, Ishikawa T, Morita YS, Toyonaga K, Yamada H, Takeuchi O, Kinoshita T, Akira S, Yoshikai Y, Yamasaki S. Direct recognition of the mycobacterial glycolipid, trehalose dimycolate, by C-type lectin Mincle. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2879–2888. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Itoh F, Yoshida S, Saijo S, Matsuzawa T, Gonoi T, Saito T, Okawa Y, Shibata N, Miyamoto T, Yamasaki S. Identification of Distinct Ligands for the C-type Lectin Receptors Mincle and Dectin-2 in the Pathogenic Fungus Malassezia. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway CA. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt 1):1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan AM, Dennehy KM, Mourão-Sá D, Faro-Trindade I, Willment JA, Taylor PR, Eble JA, Reis e Sousa C, Brown GD. CLEC-2 is a phagocytic activation receptor expressed on murine peripheral blood neutrophils. J Immunol. 2009;182:4150–4157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity. 2002;16:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre L, Lugo-Villarino G, Meunier E, Valentin A, Olagnier D, Authier H, Duval C, Dardenne C, Bernad J, Lemesre JL, et al. The C-type lectin receptors dectin-1, MR, and SIGNR3 contribute both positively and negatively to the macrophage response to Leishmania infantum. Immunity. 2013;38:1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibundgut-Landmann S, Gross O, Robinson M, Osorio F, Slack E, Tsoni S, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Brown G, Ruland J, Reis E Sousa C. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:630–638. doi: 10.1038/ni1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobato-Pascual A, Saether PC, Fossum S, Dissen E, Daws MR. Mincle, the receptor for mycobacterial cord factor, forms a functional receptor complex with MCL and Fc ε RI γ. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:3167–3174. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long KM, Whitmore AC, Ferris MT, Sempowski GD, McGee C, Trollinger B, Gunn B, Heise MT. Dendritic cell immunoreceptor regulates Chikungunya virus pathogenesis in mice. J Virol. 2013;87:5697–5706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01611-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglinao M, Klopfleisch R, Seeberger PH, Lepenies B. The C-Type Lectin Receptor DCIR Is Crucial for the Development of Experimental Cerebral Malaria. J Immunol. 2013;191:2551–2559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoud AH, Yona M, Xue D, Chouiali F, Alturaihi H, Ablona A, Mourad W, Piccirillo CA, Mazer BD. Dendritic cell immunoreceptor: a novel receptor for intravenous immunoglobulin mediates induction of regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:853–863. e855. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:991–1045. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Toyonaga K, Mori D, Kakuta S, Hoshino Y, Oyamada A, Yamada H, Ono K.-i., Suyama M, Iwakura Y, et al. C-type Lectin MCL Is an FcR γ - Coupled Receptor that Mediates the Adjuvanticity of Mycobacterial Cord Factor. Immunity. 2013;38:1050–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mócsai A, Ruland J, Tybulewicz VLJ. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:387–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourao-Sa D, Robinson MJ, Zelenay S, Sancho D, Chakravarty P, Larsen R, Plantinga M, Van Rooijen N, Soares MP, Lambrecht B, Reis e Sousa C. CLEC-2 signaling via Syk in myeloid cells can regulate inflammatory responses. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3040–3053. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann K, Castineiras-Vilarino M, Hockendorf U, Hannesschlager N, Lemeer S, Kupka D, Meyermann S, Lech M, Anders HJ, Kuster B, et al. Clec12a is an inhibitory receptor for uric acid crystals that regulates inflammation in response to cell death. Immunity. 2014;40:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng G, Sharma K, Ward SM, Desrosiers MD, Stephens LA, Schoel WM, Li T, Lowell CA, Ling C-C, Amrein MW, Shi Y. Receptor-independent, direct membrane binding leads to cell-surface lipid sorting and Syk kinase activation in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2008;29:807–818. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier B, Launay P, Kanamaru Y, Moura IC, Pfirsch S, Ruffié C, Hénin D, Benhamou M, Pretolani M, Blank U, Monteiro RC. Identification of FcalphaRI as an inhibitory receptor that controls inflammation: dual role of FcRgamma ITAM. Immunity. 2005;22:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin LF, Salio M, Griessinger E, Anjos-Afonso F, Craciun L, Chen J-L, Keller AM, Joffre O, Zelenay S, Nye E, et al. Characterization of human DNGR-1+ BDCA3+ leukocytes as putative equivalents of mouse CD8{alpha}+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1261–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter M, Gross O, Kays S, Ruland J, Nimmerjahn F, Saijo S, Tschopp J, Layland LE, Prazeres da Costa C. Schistosoma mansoni triggers Dectin-2, which activates the Nlrp3 inflammasome and alters adaptive immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20459–20464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010337107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJ, Osorio F, Rosas M, Freitas RP, Schweighoffer E, Gross O, Verbeek JS, Ruland J, Tybulewicz V, Brown GD, et al. Dectin-2 is a Syk-coupled pattern recognition receptor crucial for Th17 responses to fungal infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2037–2051. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers NC, Slack EC, Edwards AD, Nolte MA, Schulz O, Schweighoffer E, Williams DL, Gordon S, Tybulewicz VL, Brown GD, Reis e Sousa C. Syk-dependent cytokine induction by Dectin-1 reveals a novel pattern recognition pathway for C type lectins. Immunity. 2005;22:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas M, Liddiard K, Kimberg M, Faro-Trindade I, McDonald JU, Williams DL, Brown GD, Taylor PR. The induction of inflammation by dectin-1 in vivo is dependent on myeloid cell programming and the progression of phagocytosis. J Immunol. 2008;181:3549–3557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo S, Ikeda S, Yamabe K, Kakuta S, Ishigame H, Akitsu A, Fujikado N, Kusaka T, Kubo S, Chung S.-h., et al. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity. 2010;32:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho Mourão-Sá, Schulz Joffre, Rogers Pennington, Carlyle, Reis E Sousa C. Tumor therapy in mice via antigen targeting to a novel, DC-restricted C-type lectin. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2098–2110. doi: 10.1172/JCI34584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho D, Joffre OP, Keller AM, Rogers NC, Martinez D, Hernanz-Falcón P, Rosewell I, Reis e Sousa C. Identification of a dendritic cell receptor that couples sensing of necrosis to immunity. Nature. 2009;458:899–903. doi: 10.1038/nature07750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho D, Reis e Sousa C. Signaling by Myeloid C-Type Lectin Receptors in Immunity and Homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:491–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho D, Reis e Sousa C. Sensing of cell death by myeloid C-type lectin receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Reiling N, Fessler C, Stephani J, Taniuchi I, Hatam F, Yildirim AO, Fehrenbach H, Walter K, Ruland J, et al. Decreased pathology and prolonged survival of human DC-SIGN transgenic mice during mycobacterial infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:6836–6845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenen H, Bodendorfer B, Hitchens K, Manzanero S, Werninghaus K, Nimmerjahn F, Agger EM, Stenger S, Andersen P, Ruland J, et al. Cutting Edge: Mincle Is Essential for Recognition and Adjuvanticity of the Mycobacterial Cord Factor and its Synthetic Analog Trehalose-Dibehenate. J Immunol. 2010;184:2756–2760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenderov K, Barber DL, Mayer-Barber KD, Gurcha SS, Jankovic D, Feng CG, Oland S, Hieny S, Caspar P, Yamasaki S, et al. Cord Factor and Peptidoglycan Recapitulate the Th17-Promoting Adjuvant Activity of Mycobacteria through Mincle/CARD9 Signaling and the Inflammasome. J Immunol. 2013;190:5722–5730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack EC, Robinson MJ, Hernanz-Falcón P, Brown GD, Williams DL, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz VL, Reis e Sousa C. Syk-dependent ERK activation regulates IL-2 and IL-10 production by DC stimulated with zymosan. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1600–1612. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa M.d.G., Reid DM, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Ruland J, Langhorne J, Yamasaki S, Taylor PR, Almeida SR, Brown GD. Restoration of pattern recognition receptor costimulation to treat chromoblastomycosis, a chronic fungal infection of the skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne A, Ma B, Boudou F, Tailleux L, Botella H, Badell E, Levillain F, Taylor ME, Drickamer K, Nigou J, et al. A murine DC-SIGN homologue contributes to early host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2205–2220. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill DM, Rossnagle E, Lowell CA, Simmons RM. Dectin-1 activates Syk tyrosine kinase in a dynamic subset of macrophages for reactive oxygen production. Blood. 2005;106:2543–2550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet SJ, Saeland E, van Kooyk Y. Sweet preferences of MGL: carbohydrate specificity and function. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Since there are PAMPs and DAMPs, there must be SAMPs? Glycan “self-associated molecular patterns” dampen innate immunity, but pathogens can mimic them. Glycobiology. 2011;21:1121–1124. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Gordon RA, Huynh L, Su X, Park Min K-H, Han J, Arthur JS, Kalliolias GD, Ivashkiv LB. Indirect inhibition of Toll-like receptor and type I interferon responses by ITAM-coupled receptors and integrins. Immunity. 2010;32:518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AA, Christou CM, James JR, Fenton-May AE, Moncayo GE, Mistry AR, Davis SJ, Gilbert RJC, Chakera A, O’Callaghan CA. The platelet receptor CLEC-2 is active as a dimer. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10988–10996. doi: 10.1021/bi901427d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch MD, Way M. Arp2/3-mediated actin-based motility: a tail of pathogen abuse. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:242–255. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells CA, Salvage-Jones JA, Li X, Hitchens K, Butcher S, Murray RZ, Beckhouse AG, Lo Y-L-S, Manzanero S, Cobbold C, et al. The macrophage-inducible C-type lectin, mincle, is an essential component of the innate immune response to Candida albicans. J Immunol. 2008;180:7404–7413. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wevers BA, Kaptein TM, Zijlstra-Willems EM, Theelen B, Boekhout T, Geijtenbeek TB, Gringhuis SI. Fungal engagement of the C-type lectin mincle suppresses dectin-1-induced antifungal immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:494–505. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S. Signaling while eating: MCL is coupled with Mincle. European Journal of Immunology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/eji.201344131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S, Ishikawa E, Kohno M, Saito T. The quantity and duration of FcRgamma signals determine mast cell degranulation and survival. Blood. 2004;103:3093–3101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S, Ishikawa E, Sakuma M, Hara H, Ogata K, Saito T. Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1179–1188. doi: 10.1038/ni.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S, Matsumoto M, Takeuchi O, Matsuzawa T, Ishikawa E, Sakuma M, Tateno H, Uno J, Hirabayashi J, Mikami Y, et al. C-type lectin Mincle is an activating receptor for pathogenic fungus, Malassezia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1897–1902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805177106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenay S, Keller AM, Whitney PG, Schraml BU, Deddouche S, Rogers NC, Schulz O, Sancho D, Reis e Sousa C. The dendritic cell receptor DNGR-1 controls endocytic handling of necrotic cell antigens to favor cross-priming of CTLs in virus-infected mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1615–1627. doi: 10.1172/JCI60644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelensky AN, Gready JE. The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. FEBS J. 2005;272:6179–6217. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-G, Czabotar PE, Policheni AN, Caminschi I, San Wan S, Kitsoulis S, Tullett KM, Robin AY, Brammananth R, van Delft MF, et al. The Dendritic Cell Receptor Clec9A Binds Damaged Cells via Exposed Actin Filaments. Immunity. 2012;36:646–657. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Angata T, Cho JY, Miller M, Broide DH, Varki A. Defining the in vivo function of Siglec-F, a CD33-related Siglec expressed on mouse eosinophils. Blood. 2007;109:4280–4287. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]