Abstract

Purpose:

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has a high risk for postoperative thromboembolic complications such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared to other surgical diseases, but the relationship between VTE and CRC in Asian patients remains poorly understood. The present study examined the incidence of symptomatic VTE in Korean patients who underwent surgery for CRC. We also identified risk factors, incidence and survival rate for VTE in these patients

Materials and Methods:

The patients were identified from the CRC database treated from January 2011 to December 2012 in a single institution. These patients were classified into VTE and non-VTE groups, their demographic features were compared, and the factors which had significant effects on VTE and mortality between the two groups were analyzed.

Results:

We analyzed retrospectively a total of 840 patients and the incidence of VTE was 3.7% (31 patients) during the follow-up period (mean, 17.2 months). Histologic subtype (mucinous adenocarcinoma) and previous history of VTE affected the incidence of VTE on multivariate analysis. There was a statistically significant difference in survival rate between the VTE and non-VTE group, but VTE wasn’t the factor affecting survival rate on multivariate analysis. Comparing differences in survival rate for each pathologic stage, there was only a significant difference in stage II patients.

Conclusion:

Among CRC patients after surgery, the incidence of VTE was approximately 3% within 1 year and development of VTE wasn’t a significant risk factor for death in our study but these findings are not conclusive due to our small sample size.

Keywords: Venous thromboembolism, Colorectal cancer, Survival rate

INTRODUCTION

A strong association between the presence of cancer and the development of acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) has been recognized ever since their early reports. Thromboembolic risk is 1.5- to 12-fold higher in cancer patients than in the general population [1–5]. This has led to an interest in better understanding the risk factors associated with the development of VTE and the effect of VTE on survival.

While the incidence of VTE is presumed to be low in Korea and other Asian countries compared with Western countries, several recent reports have indicated that it is increasing, and that there may be a need for routine prophylaxis [6,7] This increase in VTE may be caused by multiple factors, such as the trend towards a more Westernized diet [8], the turn effects of gut flora, and advances in diagnostic technology that have improved VTE detection [6,8].

Among different types of cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC) is associated with a high risk for postoperative thromboembolic complications such as VTE [5,9].

The relationship between VTE and treatment of CRC in Asian patients remains poorly understood. To our knowledge, one study has investigated VTE in Korean patients who underwent surgery for CRC [8]. However, this study only reported the relationship between the occurrence of VTE and surgery for CRC, and did not report the survival or prognosis of patients with VTE after surgery for CRC.

The present study examined the incidence of symptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary artery embolism (PE) in Korean patients who underwent surgery for CRC. We also identified risk factors, incidence and survival rate for VTE in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present retrospective study involved patients identified from the CRC database treated from January 2011 to December 2012 in Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic Medical Center. The database contained prospectively collected information on all consecutive patients who underwent surgery for CRC. Surgery was performed by one of three surgeons, all qualified, experienced colorectal surgeons.

All the patients were examined with abdominal computed tomography (CT) within a month preoperatively. We checked all patients’ preoperative D-dimer level.

All patients underwent mechanical thromboprophylaxis with either graduated compression stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices which were applied from the operation day until postoperative day 3–4.

Routine anticoagulation was not performed except in patients with coronary artery disease with stents, atrial fibrillation and preoperative VTE. Anticoagulation with heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was continued in these patients until 12 hours before surgery.

We checked the D-dimer level at postoperative day 7. If the D-dimer level was elevated or the patient had pretibial pitting edema, we performed a duplex sonography of the lower extremities.

We checked for CRC recurrence by abdominal-pelvic CT after postoperative 3 months and repeated every 6 months.

During the follow-up duration, we diagnosed PE, splenic vein thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis, superior mesenteric vein thrombosis and renal vein thrombosis by detecting the presence of thrombus in CT and by D-dimer level elevation. DVT was diagnosed by Doppler and D-dimer elevation with pretibial pitting edema.

The patients were classified into VTE and non-VTE groups and risk factors were recorded according to the 2010 Caprini risk assessment model [10]: age, gender, body mass index, comorbidity, history of major surgery or orthopedic surgery, immobilization, VTE history and other risk factors (smoking, stage, history of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, histology, location of CRC and postoperative complications - postoperative ileus, pneumonia and anastomotic leakage).

We compared the demographic features between the VTE and non-VTE groups by chi square and independent sample t-tests, and the overall survival rate between the two groups by Kaplan-Meier survival method and log-rank test. We analyzed the significance of factors which had an effect on VTE and mortality by Cox proportional hazards model. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent risk factors. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate significance. Statistical analyses were carried out with PASW Statistics 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Institutional review board approval of our study was completely required in Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic Medical Center (IRB No. KC13RISE0527).

RESULTS

Among 896 CRC patients operated from January 2011 to December 2012, we excluded 56 patients: 4 patients who were diagnosed of VTE during preoperative evaluation, 17 patients who expired or were lost to follow-up within 3 months after CRC surgery and 35 patients who were operated for recurrent CRC.

We analyzed retrospectively a total of 840 patients. The mean duration of follow-up was 17.2 months (range, 3.1–34.7 months). There were 53 deaths (6.3%) and 69 patients (8.2%) were lost to follow-up during this period. There were 31 patients (3.7%) diagnosed of VTE during the follow-up: 6 patients (0.7%) with DVT, 8 patients (1%) with PE, 12 patients (1.4%) with portal vein thrombosis, 10 patients (1.2%) with other types of venous thrombosis (including superior mesenteric, renal and splenic vein thrombosis) and 1 patient (0.1%) with DVT combined with PE. All patients were prescribed with anticoagulation after diagnosis, and inferior vena cava (IVC) filter was inserted in the one patient with combined DVT and PE.

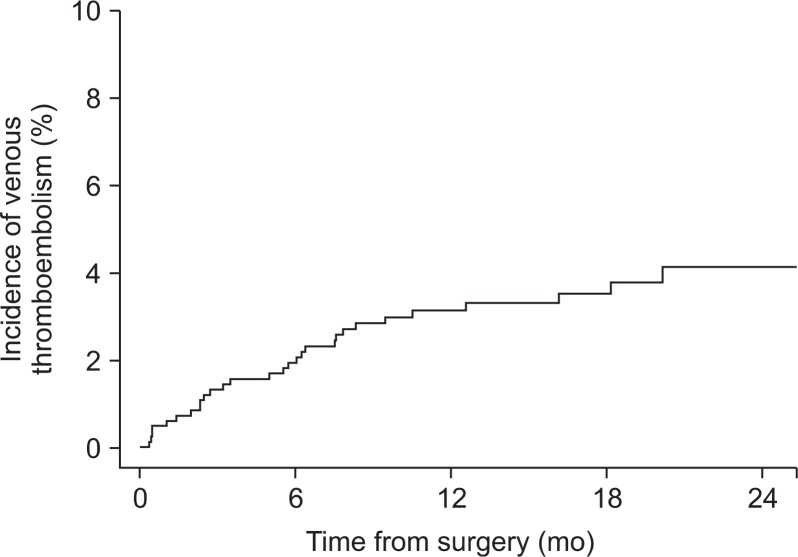

The incidence of VTE at 6 and 12 months after surgery was 1.93% and 2.99%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Incidence of venous thromboembolism after colorectal cancer surgery.

We compared the demographic characteristics between the VTE and non-VTE groups. There were significant differences in pre- (P=0.023) and postoperative chemotherapy (P=0.01), death (P=0.022) and stage (P<0.001; Table 1). There were no other factors in our study affecting VTE occurrence except histologic subtype (mucinous adenocarcinoma) and history of VTE on multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between non-VTE and VTE groups

| Characteristic | Non-VTE group (n=809) | VTE group (n=31) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | <41 | 36 (4.45) | 1 (3.23) | 0.843 |

| 42–60 | 322 (39.80) | 12 (38.71) | ||

| 61–74 | 339 (41.90) | 12 (38.71) | ||

| ≥75 | 112 (13.84) | 6 (19.35) | ||

| Sex | Male | 500 (61.80) | 19 (61.29) | 0.954 |

| Female | 309 (38.20) | 12 (38.71) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <25 | 501 (61.93) | 21 (67.74) | 0.512 |

| ≥25 | 308 (38.07) | 10 (32.26) | ||

| Stage of CRC | Stage I | 254 (31.40) | 4 (12.90) | <0.001 |

| Stage II | 201 (24.85) | 6 (19.35) | ||

| Stage III | 259 (32.01) | 7 (22.58) | ||

| Stage IV | 95 (11.74) | 14 (45.16) | ||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 134 (16.56) | 10 (32.26) | 0.023 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 463 (57.23) | 25 (80.65) | 0.010 | |

| Radiotherapy | 149 (18.41) | 4 (12.90) | 0.435 | |

| Location of cancer | Cecum or Ascending colon | 154 (19.04) | 11 (35.48) | 0.250 |

| Transverse colon | 47 (5.81) | 2 (6.45) | ||

| Descending colon | 41 (5.07) | 1 (3.23) | ||

| Rectosigmoid colon | 567 (70.09) | 17 (54.84) | ||

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma | 788 (97.40) | 29 (93.55) | 0.183 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 15 (1.85) | 2 (6.45) | ||

| Others | 6 (0.74) | 0 | ||

| Death | 48 (5.93) | 5 (16.13) | 0.022 | |

| History of major surgery | 91 (11.25) | 2 (6.45) | 0.404 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 145 (17.92) | 3 (9.68) | 0.237 | |

| Hypertension | 338 (41.78) | 12 (38.70) | 0.743 | |

| History of smoking | Non smoking | 682 (84.30) | 25 (80.65) | 0.296 |

| Current smoker | 71 (8.78) | 5 (16.13) | ||

| Ex smoker | 56 (6.92) | 1 (3.23) | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 36 (4.45) | 2 (6.45) | 0.599 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 6 (0.74) | 0 | 0.630 | |

| Cerebral vascular accident | 30 (3.71) | 2 (6.45) | 0.434 | |

| Chronic renal failure | 10 (1.24) | 0 | 0.533 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 14 (1.73) | 1 (3.23) | 0.537 | |

| Immobilization | 21 (2.60) | 2 (6.45) | 0.197 | |

| History of previous other malignancy | 52 (6.43) | 2 (6.45) | 0.996 | |

| History of VTE | 4 (0.49) | 1 (3.23) | 0.052 | |

| History of fracture in lower extremities or hip | 33 (4.08) | 1 (3.23) | 0.813 | |

| Postoperative anastomotic leakage | 19 (2.35) | 1 (3.23) | 0.753 | |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 23 (2.84) | 1 (3.23) | 0.900 | |

| Postoperative ileus | 57 (7.05) | 1 (3.23) | 0.410 | |

| Postoperative bleeding | 3 (0.37) | 0 | 0.734 | |

Values are presented as number (%).

VTE, venous thromboembolism; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysisa for incidence of VTE after colorectal cancer surgery

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of CRC | |||

| Stage I | 1.000 | ||

| Stage II | 1.023 | 0.251–4.170 | 0.975 |

| Stage III | 0.636 | 0.136–2.977 | 0.566 |

| Stage IV | 3.179 | 0.778–12.981 | 0.107 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 1.541 | 0.595–3.991 | 0.373 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 3.087 | 0.924–10.310 | 0.067 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.480 | 0.138–1.665 | 0.247 |

| Location | |||

| Cecum and ascending colon | 1.000 | - | |

| Transverse colon | 0.569 | 0.108–2.988 | 0.505 |

| Descending colon | 0.271 | 0.034–2.187 | 0.220 |

| Rectosigmoid colon | 0.423 | 0.183–0.977 | 0.044 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.000 | - | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 4.712 | 1.030–21.553 | 0.046 |

| History of major surgery | 0.522 | 0.102–2.679 | 0.436 |

| History of bed rest | 1.983 | 0.422–9.317 | 0.386 |

| History of previous other malignancy | 2.954 | 0.569–15.334 | 0.197 |

| History of VTE | 14.529 | 1.588–132.957 | 0.018 |

| Postoperative anastomotic leakage | 2.297 | 0.247–21.327 | 0.464 |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 3.490 | 0.400–30.456 | 0.258 |

| Postoperative ileus | 0.228 | 0.027–1.918 | 0.174 |

VTE, venous thromboembolism; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Cox proportional hazards model.

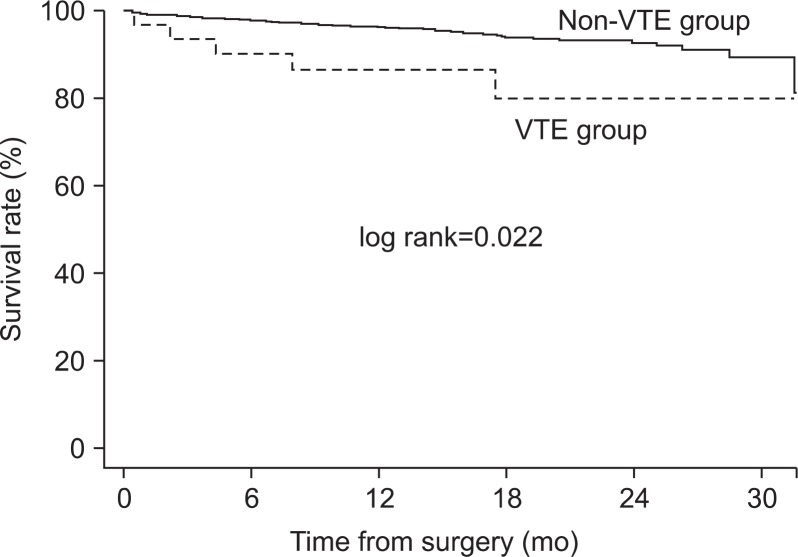

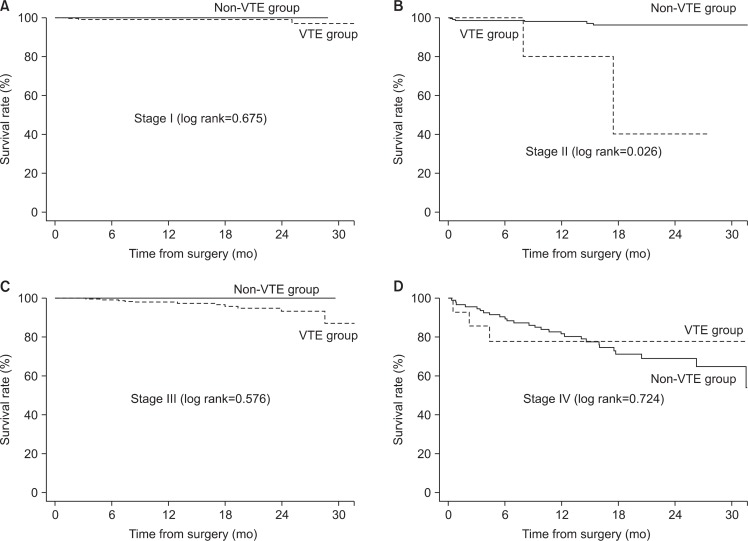

There was a statistically significant difference in survival rate between the two groups (log rank=0.022; Fig. 2). However, VTE wasn’t the factor affecting survival rate on multivariate analysis. Stage of CRC, histologic subtype, history of major operation, postoperative ileus and postoperative pneumonia affected the survival rate (Table 3). When comparing mortality according to stage of CRC, there was no difference in survival rate between the VTE and non-VTE group for stage III (log rank=0.576) and stage IV (log lank=0.724), but the difference in stage II (log rank=0.026) was significant (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of survival rate between venous thromboembolism (VTE) group and non-VTE group.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysisa for survival rate after colorectal cancer surgery

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of CRC | |||

| Stage I | 1.000 | - | |

| Stage II | 6.346 | 1.449–27.788 | 0.014 |

| Stage III | 9.009 | 2.060–39.401 | 0.004 |

| Stage IV | 45.451 | 11.006–187.695 | <0.001 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 0.991 | 0.465–2.111 | 0.981 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 0.436 | 0.208–0.914 | 0.028 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.524 | 0.185–1.484 | 0.224 |

| Location | |||

| Cecum and ascending colon | 1.000 | - | |

| Transverse colon | 1.370 | 0.462–4.060 | 0.570 |

| Descending colon | 1.514 | 0.540–4.242 | 0.430 |

| Rectosigmoid colon | 0.740 | 0.371–1.475 | 0.392 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.000 | - | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 3.459 | 1.027–11.648 | 0.045 |

| History of major surgery | 2.270 | 1.001–5.148 | 0.050 |

| History of bed rest | 2.231 | 0.727–6.847 | 0.161 |

| History of previous other malignancy | 0.593 | 0.147–2.388 | 0.462 |

| History of VTE | 2.009 | 0.219–18.445 | 0.388 |

| Postoperative anastomotic leakage | 0.402 | 0.051–3.180 | 0.388 |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 3.520 | 1.182–10.481 | 0.024 |

| Postoperative ileus | 3.497 | 1.584–7.721 | 0.002 |

| VTE after colorectal cancer surgery | 2.290 | 0.810–6.475 | 0.118 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Cox proportional hazards model.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of survival rate between venous thromboembolism (VTE) group and non-VTE group according to the stage. (A) Stage I, (B) stage II, (C) stage III, (D) stage IV.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that VTE is the most common cause of 30-day mortality among patients with cancer who undergo surgery [11]. Cancer patients requiring curative abdominal surgery are considered to be at a particularly high risk for VTE, and thromboprophylaxis is strongly recommended [12]. Occurrence of VTE in CRC has a significant adverse effect on survival, which is a result that has previously been reported [5,13]. The 2-year cumulative incidence of death among patients who never developed VTE was 35% versus 52% for patients who developed VTE [13]. Some reports assumed that the development of VTE in a portion of these patients reflects the presence of a biologically more aggressive cancer that, in turn, leads to reduced survival and this effect is much more likely to be measurable among patients with better prognosis. However this analysis did not adjust for comorbidities, tumor histology, location, or operations [13,14].

Despite a long-recognized association between cancer and thrombosis, few studies have reported the actual incidence of VTE among patients with CRC in Asia, and it appears that no study to date has investigated the rates and risk factors regarding VTE in patients undergoing surgery for CRC in particular. There was one randomized controlled clinical trial in Asia that focused specifically on colorectal patients. In this study, the incidences of DVT and PE in patients undergoing surgery for CRC and receiving LMWH were 3% and 1.7%, respectively [7]. In other Asian studies, the incidence of symptomatic DVT and PE after CRC surgery were from 0.85% to 2% [8]. The incidence of our study was similar to these studies. However, Chandra et al. [15] published in 2013 the results of a study of 254 patients who were given LMWH for 28 days in which the reported incidence of VTE was 1.18% at 30 days. Holwell et al. [16] reported a study of 150 patients with heparinization for 8 days (median duration), and the reported incidence of VTE was 4% after 90 days. Overall, our incidences were lower than those reported in Western countries, even though the incidence of VTE in Asian patients seems to be increasing.

In our study, the factors which affected the incidence of VTE were histologic subtype (mucinous adenocarcinoma) and previous VTE history. Other study showed that cancer stage and VTE history were factors affecting the occurrence of DVT and PE in CRC patients after surgery [17]. However, the number of patients with VTE in our study was small, limiting the analysis of factors affecting the occurrence of DVT and PE. Also, many factors were neglected due to under-diagnosis. In some cancers, the histologic subtype was strongly associated with VTE. Many investigators have associated mucinous adenocarcinomas with a greatest risk of DVT and PE [18,19] which are in accordance with the analysis of CRC in our study [13].

Our study showed a statistically significant difference in survival rate for VTE patients, but VTE was not associated with survival rate on multivariate analysis. Yet, many reports about cancer and VTE showed differences in survival rate between VTE and non-VTE groups [4,9]. In our study, there were differences between the two groups for stage II patients only.

The present study has several limitations including the retrospective study design and the small number of patients in each treatment group. The retrospective nature may have resulted in an underestimation of the incidence of VTE because we could only identify patients with symptomatic and objectively verifiable VTE. We did not observe a statistically significant difference in overall survival comparing the subset of patients who developed VTE and those who did not, but this finding is not conclusive due to our small sample size.

CONCLUSION

Among patients with CRC after surgery, approximately 3% developed VTE within 1 year. Significant risk factors associated with the development of VTE included previous VTE history and histologic subtype (mucinous adenocarcinoma). Development of VTE was not a significant risk factor for death in our study but this finding is not conclusive due to our small sample size.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fennerty A. Venous thromboembolic disease and cancer. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:642–648. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.046987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heit JA. Cancer and venous thromboembolism: scope of the problem. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 1):5–10. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012003S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prandoni P, Falanga A, Piccioli A. Cancer and venous thromboembolism. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:401–410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rickles FR, Levine MN. Epidemiology of thrombosis in cancer. Acta Haematol. 2001;106:6–12. doi: 10.1159/000046583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sørensen HT, Mellemkjaer L, Olsen JH, Baron JA. Prognosis of cancers associated with venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1846–1850. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kum CK, Sim EK, Ngoi SS. Deep vein thrombosis complicating colorectal surgery in the Chinese in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:895–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho YH, Seow-Choen F, Leong A, Eu KW, Nyam D, Teoh MK. Randomized, controlled trial of low molecular weight heparin vs. no deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis for major colon and rectal surgery in Asian patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:196–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02237127. discussion 202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SS, Yu CS, Yoon YS, Yoon SN, Lim SB, Kim JC. Symptomatic venous thromboembolism in Asian colorectal cancer surgery patients. World J Surg. 2011;35:881–887. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0957-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borly L, Wille-Jørgensen P, Rasmussen MS. Systematic review of thromboprophylaxis in colorectal surgery -- an update. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caprini JA. Risk assessment as a guide for the prevention of the many faces of venous thromboembolism. Am J Surg. 2010;199(1 Suppl):S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agnelli G, Bolis G, Capussotti L, Scarpa RM, Tonelli F, Bonizzoni E, et al. A clinical outcome-based prospective study on venous thromboembolism after cancer surgery: the @RISTOS project. Ann Surg. 2006;243:89–95. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000193959.44677.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AY, Levine MN. Venous thromboembolism and cancer: risks and outcomes. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I17–I21. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078466.72504.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcalay A, Wun T, Khatri V, Chew HK, Harvey D, Zhou H, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with colorectal cancer: incidence and effect on survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1112–1118. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, Zhou H, White RH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:458–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra R, Melino G, Thomas M, Lawrence MJ, Hunter RA, Moore J. Is extended thromboprophylaxis necessary in elective colorectal cancer surgery? ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:968–972. doi: 10.1111/ans.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holwell A, McKenzie JL, Holmes M, Woods R, Nandurkar H, Tam CS, et al. Venous thromboembolism prevention in patients undergoing colorectal surgery for cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:284–288. doi: 10.1111/ans.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna N, Bikov KA, McNally D, Onwudiwe NC, Dalal M, Mullins CD. Impact of venous thromboembolism on mortality of elderly Medicare patients with stage III colon cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17:1191–1197. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buller HR, van Doormaal FF, van Sluis GL, Kamphuisen PW. Cancer and thrombosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical presentations. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):246–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falanga A, Rickles FR. Pathophysiology of the thrombophilic state in the cancer patient. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1999;25:173–182. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]