Abstract

In their journey to acquire the ability to fertilize the egg, numerous intracellular signaling systems are activated in spermatozoa, leading to an increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Although the JAK/STAT signaling pathway is usually associated with the activation of transcription of specific genes, our laboratory previously demonstrated the presence of the IL6 receptor (IL6R) and the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) in human spermatozoa, a cell that is mostly transcriptionally inactive. In order to determine the importance of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, our objectives were to identify and characterize the mediators of this system in human sperm. Cell fractionation and surface biotinylation assays clearly demonstrated that IL6R is expressed at the sperm membrane surface. The kinase JAK1 is enriched in membrane fractions and is activated during human sperm capacitation as suggested by its increase in phosphotyrosine content. Many signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins are expressed in human sperm, including STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5, and STAT6. Among them, only STAT1 and STAT5 were detected in the cytosolic fraction. All the detected STAT proteins were enriched in the cytoskeletal structures. STAT4 was present in the perinuclear theca, whereas JAK1, STAT1, and STAT5 were detected in the fibrous sheath. Indirect immunofluorescence studies showed that JAK1 and STAT1 colocalized in the neck region and that STAT4 is present at the equatorial segment and flagella. The presence of STAT proteins in sperm structural components suggests that their role is different from their well-known transcription factor activity in somatic cells, but further investigations are required to determine their role in sperm function.

Keywords: cytoskeleton, gamete biology, intracellular signaling, protein kinases, signal transduction, sperm, sperm capacitation, STAT proteins, tyrosine phosphorylation

Many mediators of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway are expressed in cytoskeletal structures from the head and flagellum of human spermatozoa, suggesting an involvement in functions other than their well-known transcription factor activity.

INTRODUCTION

Spermatozoa must undergo numerous biochemical and cellular modifications to become competent at fertilizing the egg [1]. Among the observed modifications, increases in membrane fluidity, intracellular pH and Ca2+ concentration, and increases in the phosphotyrosine content of specific proteins have been reported [2]. These changes, collectively called capacitation, occur naturally in the female reproductive tract during sperm transit to the fertilization site, suggesting that factors secreted by the endometrial and oviduct epithelial cells trigger sperm intracellular signaling events that make sperm competent for fertilization [3–7].

An increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation is an important event that occurs during sperm capacitation and is considered an indicator of sperm ability to interact with the egg [8, 9]. Studies from different groups have demonstrated that, in human, the increase in protein phosphotyrosine content is regulated directly or indirectly by oxygen derivatives, Ca2+, cAMP, and cholesterol efflux [10–15]. On the other hand, the kinases that are directly involved in this process remain to be clearly identified. The presence and activity of the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase SRC has been reported in sperm [16–19], and the mechanisms by which it affects sperm motility and/or capacitation remain to be clearly established [20].

TYK2 is a member of the JAK/STAT family of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that has been detected in spermatozoa [21]. As phosphorylation of STAT proteins occurred when spermatozoa were incubated in the presence of cytokines, this suggests that the JAK/STAT signaling pathway is present in sperm and that it can be activated [21, 22]. JAK1 is another kinase activated by cytokines that is present in human sperm [4]. In somatic cells, the JAK1-mediated pathway is triggered by cytokines from the IL6 family [23]. To activate cells, IL6 requires the heterodimerization of the ligand-binding IL6R and two signal transducer subunits, GP130 (official symbol IL6ST), forming together a nontyrosine kinase receptor [24]. IL6ST is constitutively associated with the tyrosine kinase JAK1 or JAK2, and specific phosphorylated tyrosine residue on IL6ST cytoplasmic tail allows the recruitment of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STATs) through their SH2 domain, which will facilitate their phosphorylation by JAK. Phosphorylated and activated STATs homo- or heterodimerize and next migrate to the nucleus, where they activate transcription of specific genes [23].

Among classical cellular components of cytokine-mediated JAK/STAT signaling pathways, many are present in sperm: IL6R and other cytokine receptors [4, 25, 26], tyrosine kinases [4, 21], and STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 [21, 22, 27, 28]. Although phosphorylation/activation of different STAT factors has been shown when sperm were treated under various conditions in different species [21, 22, 27], the kinase involved in the activation of sperm STAT proteins was not identified. Furthermore, since spermatozoa are terminally differentiated cells with very little or no gene transcription activity, the role and importance of STATs in sperm functions remain to be elucidated. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to identify which members of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway are present in human spermatozoa in order to further characterize their role during capacitation or other sperm function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experiments were conducted with the approval of the ethics committee for research on human subjects from Laval University and the Laval University Medical Center (CHUQ-CHUL). Mice were treated and housed according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the Laval University Animal Care Committees.

Biological Material

Semen samples were obtained by masturbation from healthy volunteers after 2–3 days of sexual abstinence. After liquefaction, the semen was layered on the top of a discontinuous gradient composed of 2-ml fractions each of 20%, 40%, and 65% and 0.1 ml of 95% percoll made isoosmotic in HEPES-buffered saline (HBS; 25 mM Hepes, 130 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 14 mM fructose, pH 7.6). Samples were next centrifuged (1000 × g, 30 min, room temperature) to isolate spermatozoa from the seminal plasma. Sperm cells at the 65%–95% interface and within the 95% percoll fraction, which represent the highly motile population, were pooled, and their concentration was determined by hematocytometer count. Spermatozoa were next processed as described below for the different experiments. Human testicular tissues were obtained with the collaboration of our local transplantation program (Québec Transplant) with family authorization. Donors, aging from 23 to 58 yr, had experienced accidental death and had no history of pathology that could affect reproductive functions. Tissues were obtained and processed as previously described [29]. Briefly, dissection was made while artificial circulation was maintained to preserve organs assigned for transplantation. Testes were dissected on ice, and tissue pieces were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4). Testes from adult CD1 and C57BL/6 (Charles River) mice were collected and directly injected with the fixative solution before being immersed for 24 h in the fixative solution.

Sperm Subcellular Fractionation

Spermatozoa washed from seminal plasma were fractionated to obtain enriched subcellular fractions as previously described [17]. First, plasma membranes were detached from sperm cells by nitrogen cavitation (600 psi for 10 min at 4°C; total cavit). The suspension was next centrifuged at 10 000 × g (20 min, 4°C) to remove small cellular debris, and the resulting supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100 000 × g for 1 h (4°C). The resulting pellet contained sperm membranes (plasma membranes), whereas the supernatant contained the cytosolic fraction (cytosol). Proteins from this latter fraction were concentrated by centrifugation using a microcon device (10-kDa cutoff; Millipore). The pellet from the 10 000 × g centrifugation, which contained mostly demembranated spermatozoa, was next subjected to sonication (three times, 30 sec each on ice; total sonic) to dislocate the heads from the flagellae and to detach other sperm membranes. This last suspension was layered on the top of a 75% Percoll solution made isotonic in HBS and centrifuged at 700 × g (15 min, 4°C). The heads were found in the pellet, and broken flagellae were present at the interface. The supernatant was centrifuged (10 000 × g, 15 min, 4°C), and the resulting supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 100 000 × g (1 h, 4°C) to pellet other residual sperm membranes.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Proteins from enriched sperm subcellular fractions were solubilized in electrophoresis sample buffer (2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM DTT, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) and heated at 100°C for 5 min. Protein concentration was evaluated using a micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) after precipitation with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Proteins from each fraction were resolved by SDS-PAGE [30], and gels were either silver stained or transferred onto PVDF membrane (Immobilin-P; Millipore) [31]. Nonspecific binding sites on the membrane were blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBS-T; 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4). The membrane was next incubated with an anti-IL6R polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-JAK1, anti-STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, or STAT6 (BD Biosciences-Transduction Laboratories) monoclonal antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. These commercial STAT antibodies are known to be highly specific and do not cross-react with any of the other STAT proteins. Polyclonal anti-STAT4 (Santa Cruz) was incubated with the PVDF membrane overnight at 4°C in blocking solution. Immunoblot was also performed with the STAT4 antibody pretreated for 8 h at 4°C with a 10-fold excess of the antigenic peptide to demonstrate its specificity. Following several washes, the membranes were incubated with a goat anti-mouse IgG or a donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 1 h. After five washes in TBS-T, immunoreactive bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Inc.) and x-ray films according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Biotinylation of Sperm Surface Proteins

Percoll-isolated sperm were washed twice with HBS (500 × g, 5 min) to remove any residual Percoll and were resuspended in HBS to 25 × 106 cells/ml. Freshly solubilized Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Pierce) was added at a final concentration of 1 mM, and the suspension was incubated for 10 min at room temperature with constant agitation. Sperm were centrifuged (500 × g, 5 min, room temperature) and washed twice by centrifugation with 1 ml HBS to remove unbound biotin reagents. Pelleted spermatozoa were next lysed on ice for 30 min with frequent vortex agitation in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.1% [w/v] SDS, 1% triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA containing 10 μg/ml each of aproptinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin, 250 μM phenylmethylsulfoxide [PMSF], and 200 μM sodium orthovanadate). The suspension was next centrifuged at 17 000 × g (20 min, 4°C) to isolate the soluble fraction to which neutravidin-conjugated sepharose beads (Pierce) were added and then incubated for 2 h at 4°C with constant rotation in order to recover biotinylated proteins. At the end of the incubation, the beads were washed 3 times with IP buffer and then eluted twice with electrophoresis sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min. Proteins were next electrophoresed and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Membranes were submitted to Western blotting as described above using anti-IL6R antibody (Santa Cruz). Since HSPA5 (Grp78) was detected mostly in human sperm cytosolic fraction [32], it was used as a negative (intracellular protein) control.

Immunoprecipitation of Sperm Proteins

Immunoprecipitation were performed following a 4-h sperm incubation (20 × 106 cells/ml) at 37°C (5% CO2 in air, 100% humidity) in modified Biggers-Whitten-Whittingham medium (BWW; 10 mM HEPES, 94.6 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.7 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 25.1 mM NaHCO3, 5.6 mM d-glucose, 21.6 mM Na lactate, 0.25 mM Na pyruvate, 0.1 mg/ml phenol red, pH 7.4 [33]) supplemented with 3 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin to induce capacitation. JAK1 tyrosine phosphorylation was investigated before and after sperm incubation. Sperm were washed in HBS (500 × g, 5 min) and then lysed in Tris-NaCl buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4) containing 1% SDS and 10 mM DTT for 5 min at 95°C. The sample was next sonicated to disrupt DNA and centrifuged at 17 000 × g (20 min, room temperature). The soluble fraction was transferred to a new 1.5-ml tube and diluted 10 times with IP buffer added with 2 mM NaF and 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and kept on ice. The resulting sample was precleared by the addition of 1 μg of commercial nonimmune mouse IgG, followed by a 1-h incubation at 4°C with continuous rotation, addition of Protein G-coated sepharose beads (Amersham), and another 1-h incubation with continuous rotation. The precleared fraction was obtained after removal of the beads by centrifugation (4500 × g, 3 min). Anti-phosphotyrosine antibody conjugated to agarose beads (PY20-agarose; BD Biosciences-Pharmigen) was added to the precleared fraction and incubated overnight at 4°C. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation, washed three times with IP buffer, and eluted twice with electrophoresis sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min. Proteins from the immune complex were electrophoresed and transferred onto PVDF membrane as described above. Membranes were next submitted to Western blotting using anti-JAK1 (BD Biosciences-Pharmigen) to determine whether JAK1 is present among the immunoprecipitated tyrosine phosphorylated sperm proteins.

Isolation of Sperm Perinuclear Theca

To isolate sperm perinuclear theca, these cells were processed as described in the sperm subcellular fractionation section up to the end of the sonication process. The sonicated homogenate was resuspended 1:1 with 1.6 M sucrose in PBS containing 500 μM PMSF (PBS-PMSF). The resulting suspension was layered on top of a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting in 1 ml of each 2.2 M and 1.8 M sucrose in PBS-PMSF and centrifuged at 15 000 × g (35 min, 4°C). The purity of the head fraction recovered in the pellet was evaluated by light microscopy, and the heads were washed twice by centrifugation (10 000 × g, 5 min, 4°C) with 1 ml HBS containing protease inhibitors (HBS+inh; 10 μg/ml each of aproptinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin; 250 μM PMSF; and a tablet of Complete Mini proteases inhibitors cocktail [Roche Diagnostics]). Perinuclear theca was isolated as previously reported for bull sperm [34]. Pelleted heads were resuspended with 1% Triton X-100 in HBS+inh for 1 h at 4°C with agitation. After centrifugation at 10 000 × g (5 min, 4°C), the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed by centrifugation with 1 ml HBS+inh. The pellet was next submitted to 1 M NaCl containing 250 μM PMSF for 1 h at 4°C with agitation, followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed prior to an overnight perinuclear theca extraction with 0.1 M NaOH containing 250 μM PMSF at 4°C with agitation. The sample was next centrifuged at 10 000 × g (5 min, 4°C). The supernatant contained the solubilized perinuclear theca, while the pellet consisted of nonextracted sperm head material.

Isolation of Sperm Fibrous Sheath

Percoll-isolated spermatozoa were washed with cold Tris 50 mM pH 9.5 containing 500 μM PMSF before being submitted to a first extraction with 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris pH 9.5, and 500 μM PMSF for 10 min at 4°C with constant end-over-end rotation. The suspension was centrifuged, and proteins in the supernatant were precipitated in 80% (v/v) acetone. The pellet was washed in Tris 50 mM pH 9.5 following by a second washes in Tris 50 mM pH 8.0, and EGTA 0.5 mM at 4°C. It was next extracted with 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 500 μM PMSF for 15 min at room temperature with frequent vortex. The suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant was recovered for precipitation in 80% (v/v) acetone while the pellet was submitted to a last extraction with 6 M urea, 20 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 500 μM PMSF for 30 min with frequent vortex agitation. At the end, the suspension was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with a 1.8 M sucrose solution containing 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 500 μM PMSF. One milliliter of the resulting suspension was deposited on a layer of 500 μl of the 1.8 M sucrose solution and centrifuged at 10 000 × g (15 min, room temperature). The supernatant (urea/DTT soluble fraction) was recovered, and proteins were then precipitated with 25% (v/v; final) TCA. Sperm fibrous sheathes, the insoluble material immobilized at the interface, were transferred in a new tube for two washes with Tris 50 mM pH 8.0 in order to remove sucrose and urea/DTT-soluble contaminants. Fibrous sheath proteins were solubilized in electrophoresis sample buffer for 5 min at 95°C, facilitated by sonication. Anti-ODF2, kindly donated by Dr. van Der Hoorn (University of Calgary), was used as a marker of sperm outer dense fibers, solubilized by the urea/DTT treatment.

Immumnofluorescence on Ejaculated Spermatozoa

Isolated spermatozoa were washed by centrifugation with HBS (500 × g, 5 min) to remove residual Percoll and resuspended in HBS to a final concentration of 20 × 106 cells/ml. Thirty-five microliters of this suspension were deposited on poly-l-lysine (0.01% v/v) coated coverslips and allowed to adhere for 30 min. They were then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. After four washes in PBS, formaldehyde fixed sperm were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and washed three more times with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100. This detergent was present (0.05%) in all subsequent solutions for JAK1 and STAT1 detection. Nonspecific sites were blocked with PBS containing 1% (w/v) fraction V bovine serum albumin (PBS/BSA) for 1 h. Sperm were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with JAK1 antibody or overnight at 4°C with STAT1 antibody. An equal concentration of commercial nonimmune mouse IgG was used as a negative control. For immunolocalization of STAT4, IL6R, or IL6ST, spermatozoa on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips were fixed-permeabilized with methanol at −20°C for 10 min instead of formaldehyde/Triton X-100. Cells were next allowed to dry before being rehydrated with PBS prior to blocking with PBS/BSA. They were next incubated overnight at 4°C with STAT4, IL6R, IL6ST antibodies, or commercial nonimmune rabbit IgG as negative control. Following several washes with PBS, sperm were incubated with an anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody conjugated to Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Jackson Immunoresearch) or AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes) or with an anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 1 h at 37°C. After several washes, the coverslips were mounted on slides using glycerol containing 1.5% (w/v) diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane as an antifading agent, and cells were observed by epifluorescence microscopy under ultraviolet illumination.

Immunohistochemistry on Human Testis

Human and mouse fixed testes were processed and embedded in paraffin by the hospital pathology department. Sections (6 μm thick) were then deparaffinized in toluene and rehydrated through bathing in decreasing alcohol concentration solutions. To limit nonspecific antibody interactions, sections were treated with 300 mM glycine and were next incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigens were unmasked by incubating sections for 10 min in 10 mM boiling sodium citrate solution at pH 6.0. Sections were brought back to room temperature and incubated in blocking solution (PBS/BSA) for 1 h. Testis sections were next incubated for 16–18 h at 4°C with anti-IL6ST (GP130) or anti-STAT4 (Santa Cruz) polyclonal antibodies diluted in PBS/BSA. Negative controls consisted of commercial nonimmune rabbit IgG (rIgG) used at the same concentration. As an additional control, STAT4 antibody was preadsorbed with a 100-fold excess of the blocking peptide (Santa Cruz) prior to immunolabeling. Sections were next washed five times in PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (PBS-T), 5 min each, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch). After several washes, sections were incubated 30 min with streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch), and positive signal was revealed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) as a chromagen. Sections were counterstained with Gill hematoxylin and mounted in water-based medium containing glycerol and Mowiol (Calbiochem; EMD Biosciences Inc.). Images were acquired using a digital camera and Image Pro-Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc.).

RESULTS

Localization of IL6 Receptor in Human Sperm

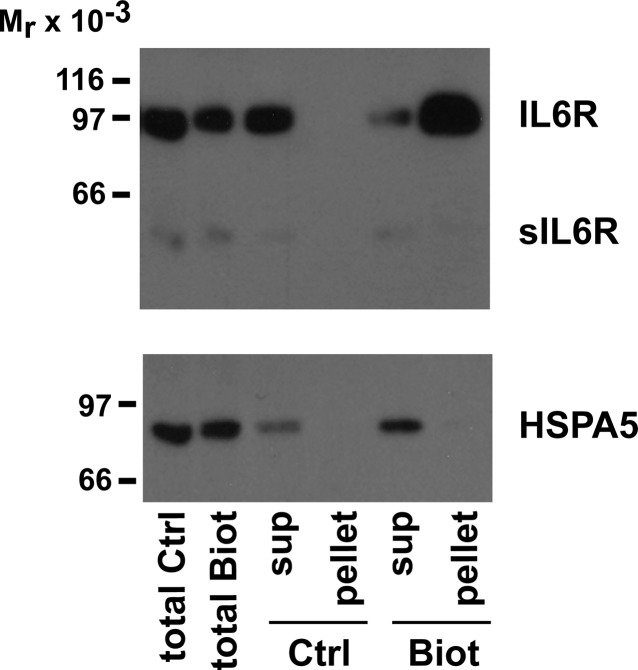

In the characterization of human sperm JAK/STAT signaling pathway, our first attempts were on the IL6 receptor. The ligand-binding subunit of this receptor, IL6R (GP80), was assessed in sperm subcellular compartments. As reported in the literature, there are two major isoforms: the membrane isoform (80 kDa), which was strongly enriched in the fraction containing the sperm plasma membranes, and the soluble isoform (sIL6R; 55 kDa), detected almost exclusively in the cytosolic fraction of spermatozoa (Fig. 1). The 80-kDa isoform was also found, although to a lower extent, in the cytosolic fraction and in the residual membranes that were further detached by sonication. The next set of experiments was designed to determine whether the membrane-associated IL6R isoform was expressed on the sperm surface. Living/moving sperm were subjected to biotinylation procedure under conditions that does not allow biotinylation of intracellular proteins. As shown in Figure 2, the 80-kDa isoform was easily detected among sperm surface biotinylated proteins, whereas the 55-kDa form (sIL6R) was not. To ensure that intracellular proteins were not biotinylated, the PVDF membrane was reprobed with an antibody against HSPA5 (Grp78), a chaperone protein previously shown to be present mostly in sperm cytosolic fraction [32]. Only a weak HSPA5 signal, if any, was detected among the biotinylated proteins. This strongly suggests that the membrane isoform of IL6R is present on the sperm surface.

FIG. 1.

IL6R in sperm subcellular fractions. Following fractionation by nitrogen cavitation, sonication, and different centrifugation, sperm proteins were electrophoresed, and gels were silver stained (A) or transferred on PVDF membrane and subjected to immunoblotting using a polyclonal anti-IL6R antibody (B). Each line contains 1.5 and 3 μg of proteins in A and B, respectively. Data shown represent one of three experiments.

FIG. 2.

Surface localization of IL6R. Living sperm were incubated in the absence (Ctrl) or presence (Biot) of biotinylation reagents and, after washes, were subjected to solubilization and precipitation with Neutravidin-coated agarose-beads. Nonprecipitated proteins (sup, supernatant) and eluted proteins from Neutravidin beads (pellet) were electrophoresed and transferred onto PDVF membrane. Western blots were performed using an anti-IL6R antibody and an anti-HSPA5 antibody as an intracellular protein control. Data shown represent one of three experiments.

The Tyrosine Kinase JAK1 in Human Sperm

Our next attempt was to identify the intracellular components of the signaling pathway related to IL6 receptor. JAK1 is the best-known tyrosine kinase associated with this receptor. As shown in Figure 3A, JAK1 was enriched in the membrane fractions obtained after cavitation (plasma membranes) or those further harvested after sonication (residual membranes). This kinase was also detected, although to a lower extent, in the fraction containing demembranated flagella (Fig. 3A). Although present in sperm membrane fractions, JAK1 was only slightly extracted by nonionic detergents (Fig. 3B). In order to determine whether this kinase is activated during sperm capacitation, its phosphotyrosine content was assessed. An increase in JAK1 phosphotyrosine content was observed when spermatozoa were incubated for 4 h under capacitating conditions (Fig. 4). These results indicate that JAK1 is present in sperm plasma membranes and is activated during capacitation.

FIG. 3.

JAK1 in sperm subcellular fractions. A) Spermatozoa were fractionated using nitrogen cavitation and sonication and different centrifugation. B) Sperm were lysed in native IP buffer, and the soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation. In both cases, proteins were submitted to electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membrane for immunoblotting with an anti-JAK1 antibody. The presence of tubulin α (TUBA) was also assessed in sperm subcellular fractions in A. Each line contains 3 μg of proteins in A and proteins extracted from 2 × 106 sperm cells in B. Data shown represent one of three experiments.

FIG. 4.

Activation of JAK1 during capacitation. Human spermatozoa were incubated for 4 h under capacitation conditions in BWW medium. They were next lysed, and phosphotyrosine containing proteins were immunoprecipitated using PY20 antibody conjugated to agarose beads (IP PY20) following a first immunoprecipitation with commercial nonimmune mouse IgG as a negative control (mIgG). JAK1 was detected among immunoprecipitated proteins by Western blot using an anti-JAK1 antibody. Data shown represent one of three experiments.

STAT Proteins in Human Sperm

The presence of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5, and STAT6 was next investigated in human sperm by Western blot procedures. In these cells, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 recognized strictly proteins with masses identical to those reported in somatic cells. For STAT4 and STAT5, other bands were detected as described below. As shown in Figure 5A, both α and β isoforms (91 and 84 kDa, respectively) of STAT1 were clearly detected in human spermatozoa. Interestingly, these two isoforms were not enriched exactly in the same subcellular fractions. The heaviest (α) form was enriched mainly in the plasma membrane and demembranated flagellar fractions, whereas the lightest (β) one was enriched in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 5A and Table 1). Although highly interesting, this difference in subcellular localization requires further investigation. STAT3 was detected in all subcellular fractions except the cytosol and the head (Fig. 5A). Although it was enriched mostly in the flagellar fraction, a slight enrichment was also noted in the membranes detached by nitrogen cavitation (Fig. 5A and Table 1). In contrast, the well-known 89 kDa STAT4 was restricted to the fractions containing the heads and the flagellae (Fig. 5A and Table1). Using this STAT4 antibody, a 70-kDa band was enriched in sperm cytosolic fraction. The nature of that protein band remains unknown, even though it disappeared when the antibody was blocked with the immunizing peptide (Fig. 5B). In the sperm head, STAT4 was present mostly in the perinuclear theca, although some of it resisted to the NaOH extraction (Fig. 6A). STAT5 was present in all subcellular fractions but the sperm heads. As for STAT1β, STAT5 was present in the cytosolic fraction. In this latter fraction, our STAT5 antibody reacted also with an unidentified ∼60-kDa protein. STAT6 was found in all sperm subcellular fractions except for the cytosolic one and was slightly enriched in flagellae. In the isolated sperm fibrous sheaths, JAK1, STAT1α and β, and STAT5 were detected, whereas STAT3 and STAT4 were extracted during the urea/DTT treatment to solubilize sperm outer dense fibers, another structural element of sperm flagella. JAK1, STAT1, and STAT5 were also present in that latter fraction (Fig. 6B). From these results, all the STAT proteins were detected in the flagellar fraction; STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 are present in the membrane fractions; STAT1 and STAT5 are present in the cytosolic fraction; and only STAT4 and STAT6 are detected in the sperm heads (Fig. 5A and Table 1).

FIG. 5.

STAT proteins in sperm subcellular fractions. A) Following fractionation by nitrogen cavitation, sonication, and different centrifugation, sperm proteins were submitted to electrophoresis and transferred on PVDF membrane for immunoblotting with anti-STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5, and STAT6 antibodies. Each line contains 3 μg of proteins. Data shown represent one of three experiments. B) The specificity of the STAT4 antibody was assessed on protein extracts from mouse and human testis and in human spermatozoa (spzs). PVDF membranes were incubated with anti-STAT4 antibody that has been preadsorbed or not with the antigenic peptide.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of STAT proteins in sperm subcellular fraction.

FIG. 6.

JAK/STAT mediators in sperm perinuclear theca and fibrous sheath. Proteins obtained during isolation of sperm perinuclear theca (A) and fibrous sheath (B) were submitted to electrophoresis and electrotransference on PVDF membrane for immunodetection with antibodies directed against JAK1, STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, or STAT5. The presence of IL6R was also assessed in these fractions; anti-ODF2 was used as a marker of outer dense fibers. Each line contains 2 μg of proteins. Data shown represent one of three experiments.

Localization of the Mediators of the JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway in Spermatozoa

The localization of the different mediators of the JAK/STAT pathway was next attempted by indirect immunofluorescence in human spermatozoa. As we previously reported [4], IL6R was localized to the entire flagellum, from the neck to the end piece (Fig. 7B). IL6ST, the signaling subunit of the receptor, was detected at the equatorial segment and at a highly localized area of the connecting piece (Fig. 7A). JAK1 and STAT1 showed very similar localization, highly restricted to a small area of the sperm neck (Fig. 7, D and E). STAT4 was detected in the equatorial segment, in the neck and midpiece regions, and at a lower level in the entire flagella (Fig. 7C). In the neck, however, its localization was not as restricted as what was observed with IL6ST, JAK1, or STAT1. Negative controls consisted of commercial nonimmune mouse or rabbit IgG instead of primary antibodies and showed no immunoreactivity (Fig. 7, H and I).

FIG. 7.

Localization of IL6R, IL6ST, JAK1, STAT1, and STAT4 on sperm. Fixed and permeabilized spermatozoa were submitted to indirect immunofluorescence using an anti-JAK1 or anti-STAT1 monoclonal antibody (D and E, respectively) or an anti-IL6R, anti-IL6ST, or anti-STAT4 polyclonal antibody (B, A, and C, respectively). Negative controls using total mouse or rabbit IgG (G or H, respectively) were shown. Corresponding phase images were shown for STAT1 (F) and rIgG (I). Equatorial segment is indicated by an arrow, flagella by an arrowhead, and neck region by an asterisk. Bar = 10 μm. Data shown represent one of three experiments.

Localization of IL6ST and STAT4 in Testis Tissues

Our next goal was to determine when, during spermatogenesis, the mediators of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway were expressed. Unfortunately, among the antibodies tested by immunohistochemical methods on human testis sections, only IL6ST and STAT4 could be consistently and significantly detected. IL6ST was detected in both peritubular space and seminiferous tubules (Fig. 8A). In the seminiferous tubules, IL6ST was found in the cytoplasm of spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids (Fig. 8C). The strongest signal, however, was observed in spermatids. In these cells, IL6ST shows association with the developing acrosome and the equatorial segment (Fig. 8C). As previously shown in mouse testis [28] (Fig. 9, B and D), STAT4 was strongly expressed in the cytoplasm and nucleus of human spermatids and associated with the developing acrosome and equatorial segment (Fig. 9, A and C). However, when the antibody was preadsorbed with the immunizing peptide, a much weaker labeling was still detected in the developing acrosome and equatorial segment in both human and mouse (Fig. 9, E and F, respectively). Nevertheless, the cytoplasmic and nuclear signal was completely lost when tissues were probed with the preadsorbed antibody. No signal was detected when human or mouse testes were probed with nonimmune commercial rabbit IgG (Fig. 9, G and H). Therefore, from these results, both IL6ST and STAT4 are strongly expressed at the spermatid stage in a very similar localization.

FIG. 8.

Localization of IL6ST in human testis. Human testis sections were submitted to immunohistochemistry using an anti-IL6ST polyclonal antibody (A and C) or total rabbit IgG as a negative control (B and D). Positive staining is shown by a brownish precipitate. Spermatogonias (Sg), spermatocytes (Sc), and spermatids (Sd) are indicated. Bar = 50 μm (A and B) and 20 μm (C and D). Data shown represent one of three experiments.

FIG. 9.

Localization of STAT4 in human testis. Human (left panels) and mouse (right panels) testis sections were submitted to immunohistochemistry using anti-STAT4 polyclonal antibody (A–D) or preadsorbed STAT4 antibody (E and F) or total rabbit IgG (G and H) as a negative control. Positive staining is shown by a brownish precipitate. Spermatogonias (Sg), spermatocytes (Sc), and spermatids (Sd) are indicated. Bar = 50 μm (A, B, and E–H) and 20 μm (C and D).

DISCUSSION

During the process of fertilization, when both male and female gametes interact, it has been shown that sperm stimulate production and secretion of cytokines by the cumulus cells surrounding the ovulated egg. In return, those secretory products would facilitate sperm capacitation [35]. However, the mechanisms by which these cytokines modulate sperm function are not characterized and require further investigations. The importance of the JAK/STAT pathway, which is a major intracellular signaling cascade triggered by numerous cytokines, is a field that remains to be investigated more deeply in sperm functions. A previous study reported that human sperm STAT1 was tyrosine phosphorylated/activated by IFNA or IFNG, while STAT4 was putatively activated by IL12 [21]. In guinea pig, capacitation-associated tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 was also demonstrated, whereas STAT4 was not affected [27]. On the other hand, the cascade of events or the enzymes involved in the activation of STAT1 remain elusive in mammalian spermatozoa. Although it would have been interesting to determine whether one or more STAT proteins and JAK1 are activated during capacitation, these functional studies are not under the scope of the present study. The goal of this investigation was to determine which players of the JAK/STAT signaling cascade are present in human sperm and in what part of the cell they are found. Here we showed that JAK1 phosphotyrosine content increases during capacitation, suggesting that its activation but its involvement in the phosphorylation/activation of spermatic STATs remains to be determined.

This study is the first to report the presence of STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 in human spermatozoa in addition to STAT1 and STAT4. In agreement with previous observation in mouse sperm [28], STAT4 was present in demembranated human sperm heads among the proteins solubilized from the perinuclear theca. In human testis sections, STAT4 was detected mainly in the cytoplasm and in the acrosomal/equatorial area of spermatids. Similar expression pattern was previously reported in mouse [28]. In ejaculated human sperm, STAT1 was detected in the neck as previously observed in guinea pig [27], while STAT4 was found at the equatorial segment. In our conditions, unlike what was previously reported in human [21] and guinea pig sperm [27], no STAT4 staining was detected on the apical region of the sperm head. When sperm subcellular localization of STAT proteins was assessed, they were all detected in the flagellar fraction, STAT1 and STAT5 being enriched in the fibrous sheath, while the other family members were present in the urea/DTT-extracted fraction, suggesting that they are associated with the sperm outer dense fibers, the axoneme, or loosely attached to the fibrous sheath. Unfortunately, in our usual conditions, we were unsuccessful at determining the localization of STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 in sperm or in testis sections by indirect immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry approaches. In mouse seminiferous tubules, STAT3 was shown to be associated with the developing acrosome of round spermatids [36].

The presence of STAT proteins in sperm structural components suggests that their role is different from their well-known transcription factor activity in somatic cells. As sperm are transcriptionally inactive or, at most, poorly active, the physiological significance of STAT proteins in sperm function remains intriguing. It has been recently demonstrated that STATs can also mediate protein-protein interactions, demonstrating that they are not exclusively restricted to DNA binding [37]. Since almost all STATs were enriched in sperm flagellum, interactions with tubulin-binding proteins, as previously demonstrated for STAT3 and stathmin [37], might occur. This hypothesis is reinforced by the association of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 with the axoneme and/or outer dense fibers as suggested by its extraction by urea/DTT treatment (Fig. 6B). Stathmin-encoding RNA is found at high levels in human testis [38], and the protein stathmin is present in meiotic and postmeiotic rat germ cells [39–41]. Therefore, these findings support ongoing studies on the role of STATs in sperm functions independently of their well-known role as transcription factors.

In this study, the presence of STAT1 in the neck region of the sperm flagellum is highly similar to the one of JAK1 which might suggest putative interactions between these two. This may be further emphasized by the same colocation of these two factors in the fibrous sheaths and the urea/DTT-extracted fractions. Since IL6ST, the signal transducing subunit of some cytokine receptor, is also detected in the neck region, a signaling cascade involving these three components may be activated according to a yet-undefined stimulus. As the IL6R is detected in the entire flagellum, including the neck area, IL6 might trigger this JAK/STAT signaling pathway, although contradictions are found in the literature concerning the effects—positive, negative, or absence of effect—of IL6 on sperm motility [26, 42, 43].

On the other hand, there are some suggestions from the literature that the tyrosine kinase JAK might also be involved in sperm motility. JAKMIP1 (Marlin-1) is a protein interacting with JAK and with microtubules [44]. It has been previously reported that JAKMIP1 is present in mature rat spermatozoa, mostly in the flagellum [45]. All together, the observations discussed above suggest a putative role for STATs in sperm motility or in molecule trafficking along microtubules. Recently, it was shown that leptin stimulates boar and human sperm motility [22, 46]. The leptin receptor, which has been shown in human and pig sperm [22, 47], usually activates the cellular JAK/STAT signaling pathway [48]. Whether leptin activates sperm motility directly or indirectly through the activation of JAK remains to be elucidated, even though it was shown to activate STAT3 in boar sperm [22].

Although the activation of sperm JAK/STAT signaling cascade was not the objective of this study, we clearly demonstrated that the members of this pathway are present in mature ejaculated sperm. From our results, it is clearly shown that the membrane form of IL6R, the ligand binding subunit of the IL6 receptor, is present on the sperm surface and that JAK1, STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 were all present in the subcellular fraction that contain sperm membranes. It is therefore likely that activation of this signaling is activated in sperm. Evidence is pointing out that many signaling pathways are implicated during sperm capacitation [49, 50], and investigations are currently undergoing to establish if the tyrosine kinase JAK1 and the different STAT proteins play a role in the process of sperm capacitation or its associated development of hyperactive motility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express special thanks to S. Goupil for his precious technical help and discussions as well as to Dr. F. Van der Hoorn (University of Calgary) for his gift of ODF2 antibody. We are also grateful to all the volunteers who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) to P.L. C.L. was supported by a Ph.D. studentship from the CIHR.

REFERENCES

- Yanagimachi R. Mammalian fertilization. : Knobil E, Neil JD. (eds.), The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1994: 189 317. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser LR. The “switching on” of mammalian spermatozoa: molecular events involved in promotion and regulation of capacitation. Mol Reprod Dev 2010; 77: 197 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington JE, Samper JC, Jones AE, Oliver SA, Burnett KM, Wright RW. In vitro interactions of cryopreserved stallion spermatozoa and oviduct (uterine tube) epithelial cells or their secretory products. Anim Reprod Sci 1999; 56: 51 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme J, Akoum A, Leclerc P. Induction of human sperm capacitation and protein tyrosine phosphorylation by endometrial cells and interleukin-6. Mol Hum Reprod 2005; 11: 141 150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero I, Ghersevich S, Caille A, Munuce MJ, Daniele SM, Morisoli L. Effects of human oviductal in vitro secretion on spermatozoa and search of sperm-oviductal proteins interactions. Int J Androl 2005; 28: 137 143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Ho P, Yeung WS. Human oviductal cells produce a factor(s) that maintains the motility of human spermatozoa in vitro. Fertil Steril 2000; 73: 479 486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung WS, Ng VK, Lau EY, Ho PC. Human oviductal cells and their conditioned medium maintain the motility and hyperactivation of human spermatozoa in vitro. Hum Reprod 1994; 9: 656 660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DY, Clarke GN, Baker HW. Tyrosine phosphorylation on capacitated human sperm tail detected by immunofluorescence correlates strongly with sperm-zona pellucida (ZP) binding but not with the ZP-induced acrosome reaction. Hum Reprod 2006; 21: 1002 1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas D, Leppens-Luisier G, Lucas H, Chardonnens D, Campana A, Franken DR, Urner F. Localization of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in human sperm and relation to capacitation and zona pellucida binding. Biol Reprod 2003; 68: 1463 1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Paterson M, Fisher H, Buckingham DW, van Duin M. Redox regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation in human spermatozoa and its role in the control of human sperm function. J Cell Sci 1995; 108 (pt 5): 2017 2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc P, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′monophosphate-dependent regulation of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in relation to human sperm capacitation and motility. Biol Reprod 1996; 55: 684 692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc P, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation and human sperm capacitation by reactive oxygen derivatives. Free Radic Biol Med 1997; 22: 643 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc P, de Lamirande E, Gagnon C. Interaction between Ca2+, cyclic 3′,5′ adenosine monophosphate, the superoxide anion, and tyrosine phosphorylation pathways in the regulation of human sperm capacitation. J Androl 1998; 19: 434 443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luconi M, Krausz C, Forti G, Baldi E. Extracellular calcium negatively modulates tyrosine phosphorylation and tyrosine kinase activity during capacitation of human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 1996; 55: 207 216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osheroff JE, Visconti PE, Valenzuela JP, Travis AJ, Alvarez J, Kopf GS. Regulation of human sperm capacitation by a cholesterol efflux-stimulated signal transduction pathway leading to protein kinase A-mediated up-regulation of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Hum Reprod 1999; 5: 1017 1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MA, Hetherington L, Aitken RJ. Identification of SRC as a key PKA-stimulated tyrosine kinase involved in the capacitation-associated hyperactivation of murine spermatozoa. J Cell Sci 2006; 119: 3182 3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson C, Goupil S, Leclerc P. Increased activity of the human sperm tyrosine kinase SRC by the cAMP-dependent pathway in the presence of calcium. Biol Reprod 2008; 79: 657 666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell LA, Nixon B, Baker MA, Aitken RJ. Investigation of the role of SRC in capacitation-associated tyrosine phosphorylation of human spermatozoa. Mol Hum Reprod 2008; 14: 235 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varano G, Lombardi A, Cantini G, Forti G, Baldi E, Luconi M. Src activation triggers capacitation and acrosome reaction but not motility in human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod 2008; 23: 2652 2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapf D, Arcelay E, Wertheimer EV, Sanjay A, Pilder SH, Salicioni AM, Visconti PE. Inhibition of Ser/Thr phosphatases induces capacitation-associated signaling in the presence of Src kinase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 7977 7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Cruz OJ, Vassilev AO, Uckun FM. Members of the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway are present and active in human sperm. Fertil Steril 2001; 76: 258 266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquila S, Rago V, Guido C, Casaburi I, Zupo S, Carpino A. Leptin and leptin receptor in pig spermatozoa: evidence of their involvement in sperm capacitation and survival. Reproduction 2008; 136: 23 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F, Graeve L. Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J 1998; 334 (pt 2): 297 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-John S, Schooltink H, Lenz D, Hipp E, Dufhues G, Schmitz H, Schiel X, Hirano T, Kishimoto T, Heinrich PC. Studies on the structure and regulation of the human hepatic interleukin-6 receptor. Eur J Biochem 1990; 190: 79 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz RK, Sellamuthu R. Receptors in spermatozoa: are they real? J Androl 2006; 27: 627 636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Harada T, Iwabe T, Taniguchi F, Mitsunari M, Yamauchi N, Deura I, Horie S, Terakawa N. A combination of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor impairs sperm motility: implications in infertility associated with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2004; 19: 1821 1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian Y, Zepeda-Bastida A, Uribe S, Mujica A. In spermatozoa, Stat1 is activated during capacitation and the acrosomal reaction. Reproduction 2007; 134: 425 433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrada G, Wolgemuth DJ. The mouse transcription factor Stat4 is expressed in haploid male germ cells and is present in the perinuclear theca of spermatozoa. J Cell Sci 1997; 110 (pt 14): 1543 1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare C, Gaudreault C, St-Jacques S, Sullivan R. P34H sperm protein is preferentially expressed by the human corpus epididymidis. Endocrinology 1999; 140: 3318 3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970; 227: 680 685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979; 76: 4350 4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance C, Fortier M, Thimon V, Sullivan R, Bailey JL, Leclerc P. Localization of Hsp60 and Grp78 in the human testis, epididymis and mature spermatozoa. Int J Androl 2010; 33: 33 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggers J, Whitten W, Whittingham D. The culture of mouse embryos in vitro. : Daniel JC., Jr (ed.), Methods in Mammalian Embryology. San Francisco: WH Freeman; 1971: 86 116. [Google Scholar]

- Oko R, Maravei D. Protein composition of the perinuclear theca of bull spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 1994; 50: 1000 1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Yanai Y, Okazaki T, Noma N, Kawashima I, Mori T, Richards JS. Hyaluronan fragments generated by sperm-secreted hyaluronidase stimulate cytokine/chemokine production via the TLR2 and TLR4 pathway in cumulus cells of ovulated COCs, which may enhance fertilization. Development 2008; 135: 2001 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Carvajal L, Medico L, Pepling M. Expression of Stat3 in germ cells of developing and adult mouse ovaries and testes. Gene Expr Patterns 2005; 5: 475 482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng DC, Lin BH, Lim CP, Huang G, Zhang T, Poli V, Cao X. Stat3 regulates microtubules by antagonizing the depolymerization activity of stathmin. J Cell Biol 2006; 172: 245 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieche I, Maucuer A, Laurendeau I, Lachkar S, Spano AJ, Frankfurter A, Levy P, Manceau V, Sobel A, Vidaud M, Curmi PA. Expression of stathmin family genes in human tissues: non-neural-restricted expression for SCLIP. Genomics 2003; 81: 400 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat JA, Fields KL, Schubart UK. Stage-specific expression of phosphoprotein p19 during spermatogenesis in the rat. Mol Reprod Dev 1990; 26: 383 390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume E, Evrard B, Com E, Moertz E, Jegou B, Pineau C. Proteome analysis of rat spermatogonia: reinvestigation of stathmin spatio-temporal expression within the testis. Mol Reprod Dev 2001; 60: 439 445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marret C, Avallet O, Perrard-Sapori MH, Localization Durand P. and quantitative expression of mRNAs encoding the testis-specific histone TH2B, the phosphoprotein p19, the transition proteins 1 and 2 during pubertal development and throughout the spermatogenic cycle of the rat. Mol Reprod Dev 1998; 51: 22 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampiao F, du Plessis SS. TNF-alpha and IL-6 affect human sperm function by elevating nitric oxide production. Reprod Biomed Online 2008; 17: 628 631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz RK, Kaplan P. Interleukin-6 enhances the fertilizing capacity of human sperm by increasing capacitation and acrosome reaction. J Androl 1994; 15: 228 233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steindler C, Li Z, Algarte M, Alcover A, Libri V, Ragimbeau J, Pellegrini S. Jamip1 (marlin-1) defines a family of proteins interacting with janus kinases and microtubules. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 43168 43177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal RL, Ramirez A, Castro M. Concha II, Couve A. Marlin-1 is expressed in testis and associates to the cytoskeleton and GABAB receptors. J Cell Biochem 2008; 103: 886 895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampiao F, du Plessis SS. Insulin and leptin enhance human sperm motility, acrosome reaction and nitric oxide production. Asian J Androl 2008; 10: 799 807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope T, Lammert A, Kratzsch J, Paasch U, Glander HJ. Leptin and leptin receptor in human seminal plasma and in human spermatozoa. Int J Androl 2003; 26: 335 341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhbeck G. Intracellular signalling pathways activated by leptin. Biochem J 2006; 393: 7 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbonetti A, Vassallo MR, Cinque B, Antonangelo C, Sciarretta F, Santucci R, D'Angeli A, Francavilla S, Francavilla F. Dynamics of the global tyrosine phosphorylation during capacitation and acquisition of the ability to fuse with oocytes in human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod 2008; 79: 649 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulsiani DR, Zeng HT, Abou-Haila A. Biology of sperm capacitation: evidence for multiple signalling pathways. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 2007; 63: 257 272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]