Abstract

Background

Globally, prolonged and obstructed labor contributed to 8% of maternal deaths which can be reduced by proper utilization of partograph during labor.

Methods

An Institution based cross-sectional study was conducted in June, 2013 on 403 obstetric care providers. A pre-tested and structured questionnaire was used to collect data. Data was entered to EpiInfo version 3.5.1 statistical package and exported to SPSS version 20.0 for further analysis. Logistic regression analyses were used to see the association of different variables.

Results

Out of 403 obstetric care providers, 40.2% utilized partograph during labor.Those who were midwives by profession were about 8 times more likely to have a consistent utilization of the partograph than general practitioners (AOR=8. 13, 95% CI: 2.67, 24.78). Similarly, getting on job training (AOR=2. 86, 95% CI: 1.69, 4.86), being knowledgeable on partograph (AOR=3. 79, 95% CI: 2.05, 7.03) and having favorable attitude towards partograph (AOR=2. 35, 95% CI: 1.14, 4.87) were positively associated with partograph utilization.

Conclusion

Partograph utilization in labor monitoring was found to be low. Being a midwife by profession, on job training, knowledge and attitude of obstetric care providers were factors affecting partograph utilization. Providing on job training for providers would improve partograph utilization.

Keywords: Ethiopia, obstetric care providers, partograph

Introduction

Partograph is a graphic record of progress of labor, maternal and fetal condition plotted against time for intrapartum monitoring1,2. Its aim is to provide a pictorial overview of labor, to alert obstetric care providers about deviations in maternal, fetal condition and progress of labor3,4.

World Health Organization recommends the universal utilization of the partograph during labor5. Routine use of partograph is helpful to make better decisions for the diagnosis and management of prolonged and obstructed labor2,4.

Globally, there were an estimated number of 289,000 maternal deaths in 2013. The sub-Saharan Africa region alone accounted for 62%(179,000) of maternal deaths followed by Southern Asia (69,000)6. In spite of, government commitment in reduction of maternal death by three-quarters over the period of 1990 to 2015, maternal mortality ratio is remained high, estimated at 676 per 100,000 live births in Ethiopia7. Obstructed labor accounted for 8% of maternal deaths8. The reported incidence of obstructed labor expected to reach 20% in developing countries9. In Ethiopia obstructed or prolonged labor accounted for 13% of maternal deaths10. The women who experience obstructed labor usually suffer from postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, puerperal sepsis and obstetric fistula11–13. Furthermore, it is highly associated with birth trauma, birth asphyxia, stillbirths, neonatal sepsis, and neonatal deaths. Besides, partograph is the best available tool but it is not widely used as it should be11. Thus; prevention of prolonged and obstructed labor by using partograph during labor is a key intervention in the reduction of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality14–16.

Data across African countries has shown that the utilization of partograph is poor despite preparing the tool that is simple and inexpensive for intra partum monitoring of labor2,14,17–23. Similarly, different studies in Ethiopia revealed low utilization of the partograph13,19,24,25. The lack of preprinted partograph in the health institutions, being a general practitioner, poor knowledge and attitude towards partograph were reason for not using partograph during labor13,19,25; However, these all challenges to the use of the partograph can be resolved by provisions of pre-service and on job training on partograph13. Little is known about the partograph utilization and its associated factors; understanding this will help police makers, stakeholders, program planners and obstetric care providers to improve the quality of intrapartum care. Hence, this study provides information on the level of partograph utilization and its associated factors among obstetric care providers in North Shoa Zone, central Ethiopia.

Methods

Study Setting

The study was conducted from June 5 to 20, 2013 in North Shoa zone, central Ethiopia. North Shoa zone is one of the eleven zones in the Amhara national, regional state which contains 24 districts. Debre brehan, the city of the Zone is located at a distance of 130km from Addis Ababa and at 795km from the capital city of the region (Bahir Dar). With regard to health facilities there are 3 primary government hospital and 1 general hospital, 86 health centers, 387 health posts, one private hospital, 3 higher clinics, 7 medium clinics and 93 lower clinics in the zone. Among private institution only one hospital and one private clinic are providing delivery services. Regarding health professionals, there are about 354 clinical nurses, 121 midwives, 98 health officers, 45 BSc nurses, 29 general practitioners and 1 obstetrician working in the zone.

Study design

An institutional based cross-sectional study design was conducted to assess the level of partograph utilization and its associated factors among obstetric care providers in North Shoa zone, central Ethiopia.

Population

The source population included all obstetric care providers working in North Shoa zone. These included midwives, nurses, doctors and health officers working in both governmental and nongovernmental health institutions. The study participants were certified health personnel who provide care for the woman during labor and delivery and who consented to participate in the study. Obstetric care providers who took different leave (annual, sick and maternity leave) for more than five days during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

Sampling methods

The total number of health institutions in North Shoa zone is 581 (4 governmental hospitals, 1 private hospital, 86 health centers, 387 health posts and 103 private owned clinics). From these institutions, 4 hospitals, 86 health centers and 2 clinics (i.e., a total of 92 health institutions) are providing obstetric care services. The total numbers of health personnel who have been providing obstetric care in these 92 institutions are 457 (Data obtained from each instution by principal investigator via preliminary survey). All institutions providing delivery services in the zone were included in the study since the total number of obstetric care providers working in the study area was small.

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula, by considering the following assumptions. The proportion (p) of partograph utilization = 57.3% (13), 95% confidence level of Z Zα/2=1.96, 5% of absolute precision, and 5 % non-response rate. Hence, the total sample size was 395. Thirty one respondents were not available during the data collection period. Since the determined sample size and study population was almost equal, we included all (403) eligible obstetric care providers.

Data collection instrument

A pre-tested and structured self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. Different relevant literature was reviewed to develop the tool and to include all the possible variables that address the objective of the study10–14,26. The instrument was pretested on 30 similar study participants who were working in other health facilities. Findings from the pretest were used to modify the instrument. The questionnaire was designed to obtain information on the professional characteristics of obstetric care providers, knowledge about partograph and their attitude towards partograph. Knowledge about partograph was measured by using eight knowledge questions. In order to produce a more objective assessment of knowledge about partograph a scoring method was devised and a knowledge score for each participant was obtained by adding up the score for correct response given to selected questions in the questionnaire. A score of mean value and above4–8 to knowledge related questions was considered as a good level of knowledge, while a score of less than mean value(0–3) indicated poor level of knowledge14. Providers' attitude towards partograph utilization was assessed by using a 5-point Likert scale as individuals responding strongly agree for positive attitude was given scores of 5 and 1 for those who responded as strongly disagree, while the above scores was reversed for negative attitude questions.

Finally the total score was dichotomized into favorable and an unfavorable attitude taking the mean score as a cutoff point (Mean score or more = favorable attitude and less than the mean score unfavorable attitude). Certified health personnel who provide care for the woman during labor and delivery were considered as an obstetric care provider. To measure the level of partograph utilization two steps had been under taken: The first step was, requesting the participants whether they have been using partograph or not (with Yes or No questions). Second step, the respondents who responded as “Yes” in the first step were required to answer” how often” they have been using partograph (occasionally, sometimes and routinely). Finally, obstetric care providers who have been using partographs routinely to monitor all laboring mothers were considered as partograph utilisers 2,4,5 and while; those who were not using partographs, those who have been using sometimes and occasionally to monitor labor were considered as non utilized. Two BSc nurses facilitated the data collection process. Both facilitators were given one days training before the actual work about the aim of the study, procedures, and data collection techniques going through the questionnaires and clarification was given on ways of collecting the data.

Data analysis

The collected questionnaire was checked manually for its completeness, coded and entered into EpiInfo version 3.5.1 statistical package, then exported to SPSS version 20.0 for further analysis. Descriptive and summary statistics were done. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association of each independent variable with the dependent variable. Variables significant in bi-variate analysis (P< 0.2) were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model to adjust the effects of cofounders on the outcome variable. Odds ratio with their 95% confidence intervals were computed to identify the presence and strength of association, and statistical significance was declared if p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of gondar and submitted to Zonal health department. Permission letter was granted from Zonal health department to respective health institutions. Written consent was obtained from each study subject prior to data collection process. Those respondents who were not willing to participate in the study were not forced to be involved. They were also informed that all data obtained from them would be kept confidential by using codes instead of any personal identifiers and is meant only for the purpose of the study.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 403 obstetric care providers were included in the study (response rate=94.5%). About half (50.4%) of obstetric care providers were males. The mean age of the respondents were 26.2 years (Standard deviation (SD) =4. 26). Most (80.4%) of them were working at the health center. Regarding their profession (45.4%) were Nurses. Two hundred thirty five (58.3%) had a diploma. The duration of practice ranged between 1 and 37 years (SD =4. 44) (Table1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of obstetric care providers in North Shoa Zone, central Ethiopia, 2013(n=403).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 203 | 50.4 |

| Female | 200 | 49.6 |

| Age in years | ||

| 20–24 | 184 | 45.7 |

| 25–29 | 180 | 44.7 |

| 30 or more | 39 | 9.6 |

| Health facilities | ||

| Health center | 324 | 80.4 |

| Hospital | 75 | 18.6 |

| Private facilities | 4 | 1 |

| Profession | ||

| Nurse | 183 | 45.4 |

| Midwifery | 111 | 27.6 |

| Health officer | 88 | 21.8 |

| General practitioner (MD) |

21 | 5.2 |

| Qualification level | ||

| Diploma | 235 | 58.3 |

| Bsc | 140 | 34.8 |

| General practitioner | 21 | 5.2 |

| MSc | 7 | 1.7 |

|

Year of experience (in years) | ||

| 1–5 | 237 | 58.8 |

| 6–10 | 140 | 34.8 |

| 11 or more | 26 | 6.4 |

Partograph utilization

The majority 327 (81.1%) of obstetric care providers reportedly utilizes partograph to monitor labor. Of those who were utilising partograph 162 (40.2%) used, routinely for all laboring mothers.

Reasons for not utilizing partograph

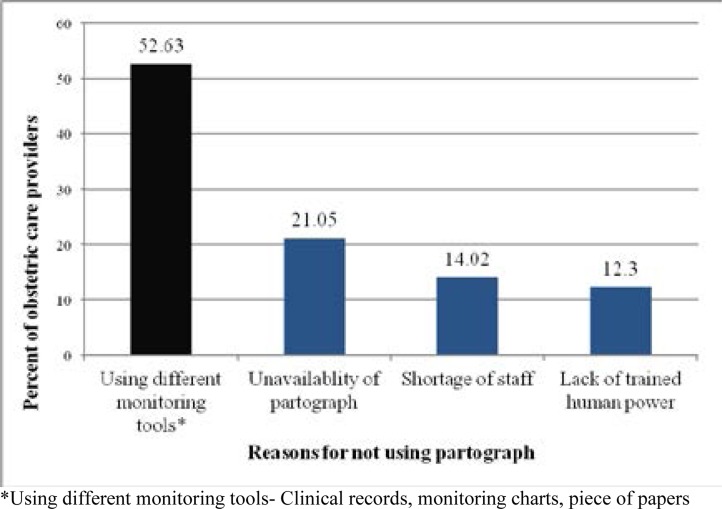

Among reasons cited by respondents for not utilising partograph to monitor labor; using different monitoring tools accounted for (52.6%). Similarly, among those who were using the partograph sometimes or occasionally; 97 (58.79%) of them were using different monitoring tools like clinical records, monitoring charts, piece of papers to monitor labor other than partograph, while 68 (41.21%) of them were citing shortage of staff as barrier for not utilizing partograph routinely during labor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons of obstetric care providers for not practicing partograph, North Shoa, Northern Ethiopia, 2013(n=76).

Knowledge and attitude of obstetric care providers towards partograph utilization

Regarding the knowledge about partograph, more than two thirds (70.5%) of the care providers were knowledgeable. Almost all (99.8%) of the participants were learned about partograph while at college or university. More than half (59.3%) of them received on the job training on partograph. The majority (83.6%) of obstetric care providers had a favorable attitude towards partograph.

Factors associated with partograph utilization

In bivariate analysis the factors found to be significantly associated with partograph utilization were: health facility they were working, profession, qualification level, on-job training, knowledge and attitude of obstetric care providers towards partograph. However, in multiple logistic regression analysis: profession, on job training, knowledge and attitude of obstetric care providers towards partograph were significantly associated with partograph utilization. Those who were midwives by profession were about 8 times more likely to have a consistent utilization of the partograph than general practitioners (AOR=8. 13, 95% CI: 2.67, 24.78). Those obstetric care providers who received on the job training on partograph were about 3 times more likely to utilize partograph than who haven't received on- job training (AOR=2. 86, 95% CI:1.69, 4.86). In addition, those who were knowledgeable on partograph were about 4 times more likely to utilize partograph than the non knowledgeable (AOR=3. 79, 95% CI: 2.05, 7.03). Furthermore, those who had a favorable attitude towards partograph utilization were about 2 times more likely to utilize partograph than those with non favorable attitude (AOR=2. 35, 95% CI: 1.14, 4.87) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate and Multivariate analyses of factors associated with partograph utilization among obstetric care providers, central Ethiopia, July, 2013(n=403).

| Variables | Partograph Utilization | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Utilized | Not utilized | COR (95% CI) | AOR(95% CI) | |

| Health facilities | ||||

| Hospitals | 37(47.4%) | 41(52.6%) | 1.44(0.88,2.37) | |

| Health centers | 125(38.5%) | 200(61.5%) | 1 | |

| Profession | ||||

| Midwifery | 81(73.0%) | 30(27.0%) | 6.75(2.39,19.01) | 8.13(2.67, 24.78)* |

| Nurse | 58(31.7%) | 125(68.3%) | 1.16(0.43, 3.14) | 1.1(0.37, 3.11) |

| Health officer | 17(19.3%) | 71(80.7%) | 0.59(0.20, 1.77) | 0.41(0.13, 1.28) |

| General practitioner | 6(28.6%) | 15(71.4%) | 1 | |

| Qualifications | ||||

| Diploma | 112(47.7%) | 123(52.3%) | 1 | |

| BSc and above | 50(29.8%) | 118(70.2%) | 0.46 (0.31, 0.71) | |

| On-job training | ||||

| Yes | 122(51.0%) | 117(49.0%) | 3.23(2.09, 5.01) | 2.86(1.69, 4.86)* |

| No | 40(24.4%) | 124(75.6) | 1 | 1 |

| Knowledge | ||||

| Knowledgeable | 138(48.6%) | 146(51.4%) | 3.74(2.26, 6.19) | 3.79(2.05, 7.03)* |

| Not Knowledgeable | 24(20.2%) | 95(79.8%) | 1 | 1 |

| Attitude | ||||

| Favorable | 145(43.0%) | 192(57.0%) | 2.18(1.20, 3.94) | 2.35(1.14, 4.87)* |

| Unfavorable | 17(25.8%) | 49(74.2%) | 1 | 1 |

= P-Value <0.05

Discussion

This study attempted to identify level of partograph utilization and associated factors among obstetric care providers in North Shoa Zone, Central Ethiopia. The level of partograph utilization was found to be 40.2% (95% CI: 35.2, 45.2). This finding is lower than the studies of Addis Ababa (57%)13, Benin (98%)27, the Niger delta of Nigeria (98.8%) and (50.6%)2, Gambia (78%)29 and South Africa (64%)28. However, it was higher than the findings of Ethiopian hospitals (13%)25, the Amhara region(29%)19, Uganda (30%)22, Nigeria (8.4%), (32.3%) and (9.8%)14,17,18. These differences might be due to differences in the place of the study that may be explained with different strategies in partograph implementation, different levels of knowledge and attitudes of care providers towards partograph utilization.

The other possible explanation could be the difference in the data collection procedure, sample size and time gap since, as time goes on, there is a change in policy, strategy and improvement in implementation of the partograph. Involvement of community health extension workers in the study of Nigeria may also another reason for this gap, as such, they may not have had adequate knowledge about partograph as compared to other professions17. In the studies of the Niger Delta (Nigeria), Gambia and South Africa; the participants were only midwives by profession with a great chance to be trained on partograph than other professions which might in turn improves their knowledge and skill of its utilization. In contrast to this, relatively large numbers of study participants from different professions participated in our study.

In the present study, the reasons for not using partograph during labor were using monitoring tools other than partograph, lack of trained human power, shortage of staff, and un-availability of the partograph. This finding is consistent with the studies in Nigeria and South Africa2,18,28.

The profession of the obstetric care provider is one of the factors for partograph utilization. Partograph utilization was higher when the providers were midwives than general practitioners. This agrees with a study conducted in nineteen Ethiopian hospitals25. This might be due to the fact that midwife obstetric care providers had more of chance of being assigned in delivery wards and consequently received training on partograph utilization which might in turn have improved their knowledge and skills to utilize partograph than others. This concept is in agreement with the study done in Amhara region19 in which midwives had better knowledge about partograph. Secondly, as obstetric care is their major duty; they might have a better understanding about partograph utilization than others.

On-job training on partograph had a significant association with partograph utilization. Obstetric care providers who received on the job training on partograph were about 3 times more likely to utilize partograph than those who had not received on- job training. This might be due to the fact that, obstetric care providers who received on-job training had better knowledge about partograph than others13,14,19; that in turn improves their partograph utilization.

Those providers who were knowledgeable about partograph were about 4 times more likely to utilize partograph than the non knowledgeable. This is in line with the study done in the Niger delta region of Nigeria2. This implies that, having knowledge about partograph is important to implement partograph during labor.

Furthermore, the study found that attitude as another factor influencing partograph utilization. Partograph utilization was significantly higher among obstetric care providers who had a favorable attitude as compared to those who had the unfavorable attitude. This could be due to the fact that, having a good attitude towards partograph utilization might come after having knowledge about partograph that may influence the utilization of partograph.

Limitations

Since information about partograph utilization was obtained from respondents through self administered questionnaires, rather than observation; response bias and social desirability bias are the potential limitations of this study. However, numerous scientific procedures were employed to minimize the possible effects. To reduce the response bias, for instance, the aim of the study was discussed with respondents in order to obtain genuine response. In addition, procedures such as supervision, pretest of data collection tool, and adequate training of data collectors and supervisors were utilized.

Conclusion

Partograph utilization in this study was found to be low. Being a midwife by profession, the presence of on job training, being knowledgeable, and having a favorable attitude by obstetric care providers were significantly associated with partograph utilization. Provision of on-job training on partograph is recommended to stakeholders and zonal health departments to improve knowledge and attitude of obstetric care providers towards partograph utilization. The obstetric care providers should monitor all laboring mothers with partographs, rather than other monitoring tools that lack the parameters of partograph.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the University of Gondar for technical and financial support. We would also like to thank the staff at North Shoa Zonal health department for their guidance and support during data collection process. Our most sincere thanks go to Dr. AO Fawole, senior lecturer at the department of obstetrics and gynecology, college of medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria for his contribution in developing the questionnaire and technical advice.

References

- 1.Mathai M. The partograph for the prevention of obstructed Labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(2):256–269. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181a4f163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opiah MM, Ofi AB, Essien EJ, Monjo E. Knowledge and utilization of partograph among Midwives in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16(1):125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavender T, Hart A, Smyth RMD. Effect of partograph use on outcomes for woman in spontaneous labor at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:1–24. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinde KK, Bangal BV, Singh KR. Study of course,of labor by using modified WHO partograph. IJBAR. 2012;3(5):391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO, author. World Health Organization partograph in management of labor. Lancet. 1994;343:1399–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN, World Bank, author. Trends in Maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013: Estimates Developed by WHO,UNICEF,UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Divisions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International, author. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nour MN. Women's health in the developing world: An Introduction to Maternal Mortality. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(2):77–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, author. The World Health Report 2005: Make every mother and Child count. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, author. Maternal Death Surveillance and Response (MDSR) Technical Guideline. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magon N. Partograph Revisited. Int J Clin Cases Investig. 2011;3(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalembo FW, Zgambo M. Public Obstetric Fistula: A hidden public health problem Sub -Saharan Africa. ASSJ. 2012;41:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yisma E, Dessalegn B, Astatkie A, Fesseha N. Knowledge and utilization of partograph among obstetric care givers in public health institutions of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2013;13(17):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fawole AO, Hunyinbo KI, Adekanle DA. Knowledge and utilization of the partograph among obstetric care givers in South West Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;12(1):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qureshi ZP, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Mutiso SM. Rapid assessment of partograph utilisation in selected maternity units in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2010;87(6):235–241. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v87i6.63081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesh D. Preventing prolonged labor by using partograph. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;8(2):1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oladapo OT, Daniel OJ, Olatunji AO. Knowledge and use of the partograph among healthcare personnel at the peripheral maternity centres in Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(6):538–541. doi: 10.1080/01443610600811243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fawole AO, Adekanle DA, Hunyinbo KI. Utilization of the partograph in primary health care facilities in Southwestern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13(2):200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abebe F, Birhanu D, Awoke W, Ejigu T. Assessment of knowledge and utilization of the partograph among health professionals in Amhara region, Ethiopia. SJCM. 2013;2(2):26–42. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyamtema AS, Urassa DP, Massawe S, Massawe A, Lindmark G, Van Roosmalen J. Partogram use in the Dar es Salaam perinatal care study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;100:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawole AO, Fadare O. Audit of use of the partograph at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. Afr J Med Sci. 2007;36(3):273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogwang S, Karyabakabo Z, Rutebemberwa E. Assessement of partograph use during labour in Rujumbura Health Sub District, Rukungiri District, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(1):27–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghebrehiwet M, Morrow Richard H. Availablity,utilization and Quality of normal delivery and emergency obstetric care in Eritrea. Jema: pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yisma E, Dessalegn B, Astatkie A, Fesseha N. Completion of the modified World Health Organization (WHO) partograph during labour in public health institutions of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 2013;10(23):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Getachew A, Ricca J, Cantor D, Rawlins B, Rosen H, Tekleberhan A, et al. Quality of care for prevention and management of common maternal and newborn complications:A study of Ethiopia's Hospitals. MCHIP. 2011 21231-3492. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maternal Health Task Force, author. The Partograph: A simple tool that is quite complicated. [Dec. 5, 2013]. http://maternalhealthtaskforce.org/2011.

- 27.Azandegbe N, Testa J, Makoutode M. Assessment of partogram utilization in Benin. Sante. 2004;14:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathibe-Neke JM, Lebeko FL, Motupa B. The partograph: A labor management tool or a Midwifery record? Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2013;5(8):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burama B, Kao HC, Gua LM, Lin CK. Partograph use among Midwives in the Gambia. AJM. 2013:7. [Google Scholar]