Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B and C viruses cause death due to liver disease worldwide among Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) positive individuals. Hepatitis B (HBV) and HIV have similar routes of transmission primarily; sexual, intravenous injections and prenatal while hepatitis C (HCV) is transmitted mainly through blood transfusion. Human immunodeficiency virus increases the pathological effect of hepatitis viruses and potentiates re-activation of latent hepatitis infections as a result of reduced immunity. The increase in use of antiretroviral (ARVs) drugs has led to longer period for patient survival and apparent increase in liver disease among HIV positive individuals.

Objective

This study aimed at determining the prevalence of HBV, HCV, their co-infection with HIV and their effect on liver cell function

Method

This was a cross sectional study conducted at the Joint Clinical Research Centre (JCRC) among HIV positive individuals attending the clinic. Patients were enrolled after obtaining a signed informed consent or assent for children below 17 years. Serum samples were collected for detection of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HCV specific antibodies and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) liver enzyme.

Results

Of the 89 patients enrolled, 20 (22.5%) had at least one hepatitis virus, 15 tested positive for HBsAg (16.9%) and 5 for HCV (5.6%), one had both viruses. Hepatitis B was more prevalent among women (13 out of 57, 22.8%) than men, (2 out of 32, 6.2%), while HCV was higher among men (4 out of 32, 12.5%) than women (1 out of 57, 1.8%). Seven of 89 patients (7.9%) had elevated ALT, indicative of liver cell injury. Of these with liver cell injury, one individual tested positive for HBsAg and another one individual tested positive for HCV specific antibodies.

Conclusion

The prevalence of HBV is high in HIV positive individuals with more women commonly infected. The Prevalence of HCV is lower than that of HBV with more men commonly infected. Co-infection of Hepatitis B and C viruses was uncommon. This study reveals a high prevalence of liver cell injury among HIV positive individuals although the injury due to HBV or HCV infection was lower than that which has been documented. From this study, the high prevalence of HBV and HCV among HIV positive individuals point to a need for screening of HIV positive individuals for the hepatitis viruses.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, HBV surface antigen, Hepatitis C virus, Hepatitis C virus antibodies, HIV, Liver damage

Introduction

Hepatitis B and C viruses are common causes of acute and chronic hepatitis. Two billion people worldwide have been infected by HBV; 400 million are chronically infected while 520,000 people die due to HBV related conditions1. Approximately 170 million people are affected with HCV worldwide, comprising 3% of the global population2.

The prevalence of HBV in general population of Uganda is 10% according to Uganda sero-survey 2004–20053 while the prevalence of HCV in the general population was not documented but different subpopulation studies indicate that it is significant. In a study done on the prevalence of HCV among hospitalized patients at JCRC indicated that it was 2.9%4 while that done on blood donor was found to be 4.1%5. Hepatitis B or C virus acute infection can lead to recovery, acute liver failure or chronic infection. Chronicity of HBV and HCV infection depends on the age, sex and immune-competence at the time of infection. In most immuno-competent adults, 5% to 10% develop chronic HBV infection, while 75% to 85% develop chronic HCV infection. Chronic infection may result in a ‘healthy carrier’ state, liver cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma. Of individuals who develop acute liver failure, 80% die with in days or weeks after infection. There is 100% transmission to newborn from highly infectious mother and 90%–95% of the children below 15years develop chronic HBV and 30 % of children below 20 years develop chronic HCV infection12,7. About 10% of HIV positive individuals are HBV antigen and HCV antibody carriers1,7. In HBV infections, 10% show co-infections with HCV and HIV1,7.

The prevalence of HIV in Uganda is 6 % among adults 15–49 years and 10% in children below five3. Human immunodeficiency virus and Hepatitis B have similar modes of transmission and hence co-infections are common and potentiate each other8,9. Also HIV increases risk of re-activation of previously existing asymptomatic and chronic HBV and HCV infections. Hepatitis B and C/HIV-co-infected individuals have a threefold risk of getting hepatotoxicity10. Therefore proper diagnosis of HBV and HCV among HIV positive individuals is important and facilitates better management of patients8.

The success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has led to HIV individuals to live longer than previously, as a result, complications of co- infections often occur8. HIV drugs like, Tenofovir and emtricitabine are effective against HBV too. It is therefore important to know the status of HBV and HCV infections before treatment with ARV. HBV and HCV therapy may cause liver toxicity in HIV co-infected patients and hence should be used with caution8.

Objective of the study

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of co-infection of HBV, HCV or both viruses among HIV positive individuals and their effect on liver cell function.

Methods

Study site and subjects

This was a cross sectional study conducted in 2007 at the Joint Clinical Research Centre (JCRC), Kampala, Uganda; a large urban HIV care and research unit. This Centre receives over 100 patients with HIV infection per day, on ART and ART naive. All HIV positive patients irrespective of duration on ART were eligible for the study. Eligible patients, who provided a signed informed consent, (and assent, for children below 17 years), were recruited in the study. A total of 89 individuals were enrolled over a period of 10 clinic days, where 9 to 10 patients were recruited by systematic random sampling each day. The sampling interval was obtained from the formula: N/n=K Where: N is the total number of patients received in the clinic in a day, n are the samples needed each day and K sampling interval. 100/9=11.1. The first patient was randomly selected and then every 11th patient was selected for the study. The patient information was obtained from the patient's case report forms from the JCRC Clinic. Patient information collected included patient identification number, age, sex, clinical data and date the blood sample was drawn.

Sample collection and processing

Three to five milliliters (mls) of blood were drawn from adults and 2 to 3 mls from children below 5 years by venipuncture under aseptic techniques into a sterile vacutainer. In the laboratory, the patient identification number on the specimen container was cross checked with that on the patients requisition form to ensure that the correct specimen was received. The quality of the sample was also checked. Samples were left on the bench for 2 hours to clot and retract. Blood was then centrifuged at 2000 rpm (440g) for 10 minutes and two aliquots of 1.0 ml serum were harvested into Eppendorff tubes labeled with patient identification number. One aliquot was immediately taken to the biochemistry lab for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) liver enzyme measurement and other stored at −80°C until time of assay for HBsAg and HCV antibody.

Measurement of Hepatitis B Surface antigen and C antibody

Hepatitis B surface antigen was detected using the hepatitis B surface antigen ELISA kits (HBsAg, Human GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Hepatitis C virus specific antibody strips (Bioline, USA) were used to determine hepatitis C infection according to manufacturer's instructions.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) estimation

Alanine aminotransaminases was analyzed on the Cobas machine (Roche Integra 400 plus, Germany), according to the manufaturer's instructions.

Data management

The patient information was entered in an excel spread sheet, and. the results appended. The data was analyzed using SPSS and Prism statistical programs.

Results

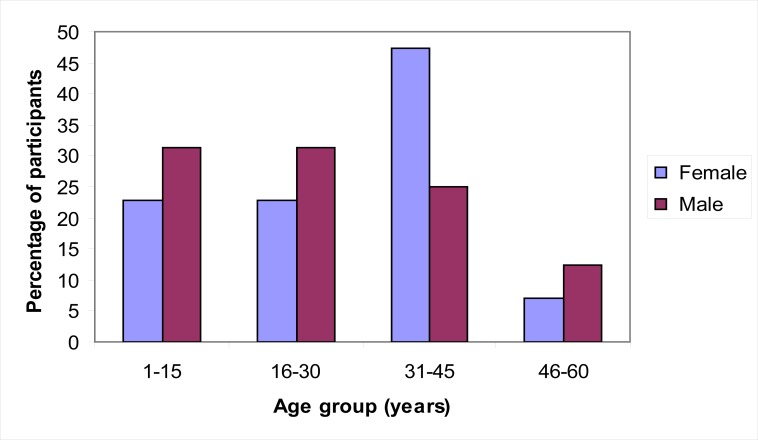

Of the 89 participants recruited, 57 (64.4 %) were female. The mean age was 27.1 years, while standard deviation was 13.9 years. Most participants were 31–45 years of age. (Figure I).

Figure I.

Distribution of participants by age and sex

Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses

Of the 89 patients studied, 15 (16.9%) tested positive for HBsAg and 5 (5.6%) tested positive for HCV antibodies. Three specimens (3.4%) had indeterminate results for HBsAg and were eliminated from further analyses (Table I).

Table I.

Hepatitis B and C Co-infection

| HCV Antibodies | ||||

| Pos (%) | Neg (%) | Total | ||

| HBs Ag | Pos | 1 (1.1) | 14 (15.7) | 15 |

| Neg | 4 (4.5) | 67 (75.3) | 71 | |

| Ind | 0 (0) | 3 (3.4) | 3 | |

| Total | 5 | 84 | 89 | |

n=89

The rate of HBV and HCV co-infection was low; one individual (1.1%) had both HBsAg and HCV specific antibodies (Table I). The prevalence of co-infection was not statistically significant (P >0.005 ANOVA). Females had the highest prevalence of HBV (13 of 57, 22.8%) which was statistically significant (P = 0.03, ANOVA). Males had the highest prevalence of HCV (4 of 32, 6.2%) which was statistically significant (P= 0.0267 ANOVA) Table II

Table II.

Prevalence of HBV and HCV by sex and age group

| Females | Males | |||||

| Number of participants (n) |

Positive HBsAg (%) |

Positive HCV antibodies |

Number of participants (n) |

Positive HBsAg (%) |

HCV antibodies (%) | |

| p | n | n (%) | n | n (%) | n (%) | |

| 13 | 3 (23.1) | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | 3 (23.1) | 0 | 10 | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | |

| 27 | 6 (22.2) | 1 (3.7) | 8 | 0 | 2 (25) | |

| 4 | 1 (25) | 0 | 4 | 1 (25) | 0 | |

| 57 | 13 (22.8) | 1 (1.7) | 32 | 2 (6.3) | 4 (12.4) | |

Liver cell injury

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was measured to determine liver cell injury since it is more specific than other liver enzyme tests. Alanine amino transferase values above 40 U/L was indicative of liver cell injury. (Table III).

Table III.

Results of alanine amino transferase liver enzyme (n=89).

| ALT | HBsAg (%) |

HCV | Neither |

| Normal | 14 (93.3) | 4 (80) | 64 (92.7) |

| Liver cell injury | 1 (6.6) | 1 (20) | 5 (7.2%) |

| Total | 15 (100) | 5 (100) | 69 (100) |

Generally seven patients had elevated ALT liver enzyme signifying liver cell injury. Of these, two patients tested positive for the hepatitis viruses: one HBsAg and one HCV specific antibodies:

Discussion

The prevalence of HBV among HIV positive individuals was found to be relatively high (16.9%) compared to the general population of Uganda (10%) according to the 2004–2005 Uganda sero-survey and Bwogi et al3,11. Hepatitis B virus and HIV share modes of transmission and hence co-infection is common. Reduced ability of the body to eliminate hepatitis B envelope (HBe) antigen and reduced immunity in HIV infected individuals lead to reactivation of the latent virus7. Also HIV infected individuals live longer due to the success of ARVs and therefore are prone to developing chronic opportunistic infection12. The prevalence of HBV was similar among all age groups. This is similar to the findings by Bwogi et al, 2009. The stable prevalence in children below 15 years suggests congenital transmission. Most children in this age bracket are not yet sexually active, and hence new infections are uncommon. Those above 15 years, although most are sexually active by this age, they are able to clear the infection11. There was a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of HBV between male and female (P = 0.03). The high prevalence of HBV among women was possibly due to high exposure to risk factors. The high prevalence of HBV among women is similar to that seen among HIV positive individuals3.

The prevalence of HCV (5.6%) was lower than HBV. This prevalence is higher than that obtained in 2002 among hospitalized patients at JCRC which was 2.9%4. This figure is also much lower than that reported among pregnant women attending Lacor hospital antenatal clinics (15%)13, which was a different study population. The increase in prevalence may be because in most developing countries like Uganda, blood for transfusion was not screened for HCV, which is the main route of transmission5,12. Very little of HCV is transmitted sexually, however HIV increases HCV RNA and hence increases chance of sexual transmission in highly sexually active groups7. In this study HCV was un- common in children below 12 years. Most children are able to clear HCV RNA from their bodies and hence less likely to develop chronic infections and antibodies2. The prevalence of HCV among male and female is statistically different (P= 0.0267). Previous studies indicate that menstruating women tend to clear HCV from their bodies due to the presence of estrogen and reduction of iron levels in children bearing women due to menstruation2,14. A similar prevalence of HCV was reported in Bangkok which showed that there were fewer women infected than men14.

This study indicates that Co-infections of HBV and HCV were un-common with 1 (1.1%) person infected with both viruses. This was not statistically significant (P> 0.05). Similar findings have been reported in Bangkok where the prevalence of HBV/HCV co-infection was 0.4%15.

Of 7 patients with elevated ALT, one tested positive for HBsAg and one for HCV antibodies. The incidence of liver cell injury among individual with hepatitis B or C viruses was not statistically significant (P =0.4, >0.05). Occurrence of liver cell injury among HBV or HCV infected individuals is lower than that documented that 10% develop liver disease. These individuals were on antiretroviral therapy (ART), which is similar to what is documented that some antiretroviral drugs help clear hepatitis B and C viruses and hence reduce effect of developing liver disease6,7. These findings are similar to those obtained by Ocama eta al, 2010 where few HIV/HBV individuals on ART had evidence of liver cell injury16. The high number of individuals with abnormal liver functions among those who tested positive for HBsAg or HCV antibodies could be due to the toxic effects of the ARVs.

Limitations and constraints

Testing of HCV antibodies does not differentiate between active and previous infections since the antibody remains in the body for a long time although the virus would have been cleared. This would necessitate doing HCV RNA which was not done in this study. . The measurement of liver enzymes as surrogate marker for liver damage in HBV and HCV infections is non-specific. More specific diagnostic tests like liver biopsy and molecular assays were required but these were not done due financial limitations

Conclusions

In this study: The prevalence of HBV and HCV among HIV positive individuals at JCRC was high although there was low evidence of liver cell injury in this population. The rate of co-infection of HBV and HCV was uncommon.

Recommendations

It is necessary to screen HIV positive individuals for HBV and HCV and treat individuals who test positive for hepatitis B and C viruses to avoid re-activation of the latent viruses. It is necessary to carry out preventive measures like vaccination of HBV among the high risk groups and have blood for transfusion screened for HCV. A similar study with a bigger sample size is recommended.

Acknowledgements

Prof. Mugyenyi Peter, Dr. Ssali Francis, Dr. Ann Nanteza, Dr. Nantiba, Dr. Kizito Hilda, Mr. Pierre Peters, Dr. Kagimba, Ms Nalukwago Sophie, Ms Koyokoyo Hellen, Mr. Nghania Frehd, Mr. Aneco James, Mr. Mulima, Ms. Nanyungi Hellena, Ms. Nanungi Maria, Mr. Tamale Bassudde, Sr. Pauline, Mr. Mugisha Kenneth, patients and guardians.

References

- 1.Massroor AM, Zahoor SZ, Akbar SM, Shaukat S, Butt AJ, Naeem A, Sharif s, Angez M. Molecular epidemiology of Hepatitis B virus genotypes in Pakistan. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2007;7:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Stephen L, Morgan Timothy R. The Natural History of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2006;3(2):47–52. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC 2006, author. Uganda HIV/AID sero- behavioural survey. 2004–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamale-Basudde TB, Mugyenyi PN. Prevalence of hepatitis c virus in patients infected with human immune deficiency virus at joint clinical research centre in Uganda. Int Conf AIDS. 2002;14(C10968):7–12. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hladik W, Kataaha P, Mermin J, Purdy M, Otekat G, Lackritz E, Alter J M, Downing R. Prevalence and screening costs of HCV virus among Ugandan blood donors. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(6):951–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun-Fan L, Tung H. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection acquired in childhood, Taiwan. Journal of viral hepatitis. 2006;14(3):147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter Miriam J. Epidemiology of viral Hepatitis and HIV Co-infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;44(1):S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soriano V, Barreiro P, Nuñez M. Management of chronic hepatitis B and C in HIV coinfected patients. Journal of antimicrobial therapy. 2006;57(5):815–818. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benhamou Yves. Antiretroviral therapy and HIV/Hepatitis B virus co infection. Journal of clinical infectious diseases. 2004;38(2):S98–S103. doi: 10.1086/381451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulkowski M S. Therapeutic issues in HIV/HCV co-infected patients. 600 North Wolfe Street, 1830 Building, Room 448, Baltimore, MD 21287-0003, USA: Viral Hepatitis center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bwogi Josephine, Braka Fiona, Makumbi Issa, Mishra Vinod, Bakamutumaho Barnabas, Nanyunja Miriam, Opio Alex, Downing Robert, Biryahwaho Benon, Lewis Rosamund F. Hepatitis B Infection is Highly endemic in Uganda: Findings From a National Serosurvey. African Health Sciences. 2009;9(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sungkanuparph S, Vibhagool A, Manosuthi W, Kiertiburanakul S, Atamasirikul K, Aumkhyan A, Thakkinstian A. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus Co-infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Thai Patients, Int Conf AIDS. Journal of Medical association, Thailand. 2004;87(11):1349–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzardini G, Ferrante P, Fabiani M, Lukwiya M, Mancuso R, Declich S, Clerici M. HCV/HIV prevalence in women attending the Ante Natal Clinic of Lacor Hospital in northern Uganda. Int Conf AIDS. 2000;13(C2407):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Highleyman L. Women and HCV, chronic Hepatitis C Is Mild in menstruating women. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2005;15(12):1411–1417. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tankhiwale SS, Khadase RK, Jalgoankar SV. Seroprevalence of anti- HCV and hepatitis B surface antigen in HIV infected patients. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2003;21(4):268–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ocama P, Castelnuovo B, Kamya MR, Kirk GD, Reynolds SJ, Kiragga A, Colebunders R, Thomas DL. Low frequency of liver enzyme elevation in HIV-infected patients attending a large urban treatment centre in Uganda. Int J STD AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]