Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a complication of pregnancy that is characterized by impaired glucose tolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. The reported prevalence of GDM varies between 0.6% and 20% of pregnancies depending on screening method, gestational age and the population studied. GDM is characterized by pancreatic β-cell function that is insufficient to meet the body’s insulin needs. Available evidence suggests that β-cell defects in GDM result from the same spectrum of causes that underline hyperglycemia in general, including autoimmune disease, monogenic causes and insulin resistance. Adipokines are proteins secreted from the adipocytes and are believed to have a metabolic influence. Our review suggests that, in GDM, various adipokines, mainly leptin and adiponectin, are dysregulated. These two adipokines might have both prognostic and pathophysiological significance in this disease.

Keywords: adipokines, adiponectin, β cell, gestational diabetes, insulin resistance, leptin

Introduction

Human pregnancy is characterized by insulin resistance, which leads to abnormal glucose tolerance in some women. Several studies suggest that inflammation also contributes to pregnancy-induced insulin resistance and development of glucose intolerance [Jacobs et al. 1994]. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is one of the most frequent complications of pregnancy that may lead to considerable risk for both the fetus and the mother [Soheilykhah et al. 2011]. Furthermore, if untreated, it may progress to type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Only a small number of potential biochemical mediators of chronic insulin resistance that frequently accompany GDM and contribute to the high risk of T2DM have been examined. It is likely that there is not a single underlying biochemical etiology. Women with GDM tend to be obese, so mechanisms promoting obesity and/or linking obesity to insulin resistance are likely to play a role. Small studies have revealed increased circulating levels of leptin, inflammatory markers tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP) and decreased levels of adiponectin in women with GDM [Meller et al. 2006]. Increased content of fat in liver and muscle has also been reported in women with previous gestational diabetes [Skvarca et al. 2013]. All of these findings are consistent with the current understanding of some potential causes of obesity-related insulin resistance.

GDM occurs in 3–7% of pregnancies [Lappas et al. 2005]. Its onset typically occurs in the second trimester due to increased insulin resistance and inadequate β-cell compensation, which is similar to T2DM. Like other forms of hyperglycemia, GDM is characterized by pancreatic β-cell function that is insufficient to meet the body’s insulin needs. Available data suggest that β-cell defects in GDM result from the same spectrum of causes that underlie hyperglycemia in general, including autoimmune disease, monogenic causes and insulin resistance. Thus, it often represents diabetes in evolution and, as such, holds great potential as a condition to study the pathogenesis of diabetes, and to develop and test strategies for diabetes prevention. GDM increases the risk of T2DM later in life and increases risk for pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia and cesarean sections. It also carries high risk for complications such as macrosomia in infants. Postnatally, these infants are at risk of developing hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, polycythemia, jaundice and respiratory distress syndrome. Individuals born to mothers with GDM have higher risk of obesity and T2DM as adults [Retnakaran et al. 2004]. It has a strong genetic component, clustering in families and particular minority ethnic groups.

Methods

Relevant English language articles were reviewed through searches of PubMed and Google Scholar using the keywords ‘gestational diabetes’, ‘β-cell dysfunction’, ‘insulin resistance’, ‘adipokines’, ‘adiponectin’ and ‘leptin’. Extensive data have been published since 1994 up to the present time on the role of β-cell dysfunction, adiponectin and leptin in GDM, while the role of other adipokines is often preliminary and needs further studies.

Review of literature and discussion

Effect of GDM on beta cell dysfunction

GDM is a complication of pregnancy that is characterized by impaired glucose tolerance with first recognition during pregnancy. It develops when the β-cell reserve is insufficient to compensate for the decreased insulin sensitivity that occurs during pregnancy. Normally, the β-cell mass adapts to physiological needs and increased functional demands [Ballesteros et al. 2011]. Changes in β-cell mass can be achieved by hyperplasia (increased cell number), hypertrophy (increased cell size) and neogenesis from progenitors. It is believed that β-cell mass expands by 50% during pregnancy. The main stimuli of β-cell proliferation during pregnancy are placental lactogens (PLs), although prolactin (Prl) and growth hormone (GH) have similar effects on β cells and are also elevated during pregnancy [Doruk et al. 2014]. Pathways involved in maintaining or augmenting β-cell mass may be affected in diabetic individuals. Additionally, recent studies reinforce the concept that polymorphisms in genes that regulate proliferation, such as TCF7L2 and CDKN2, are linked with T2DM in humans [Retnakaran et al. 2005]. Although adult pancreatic ducts retain the ability to generate new endocrine cells in response to certain stimuli, most new adult β cells arise from preexisting β cells [Kautzky-Willer et al. 2001]. During pregnancy, maternal insulin demands increase due to the insulin resistance which is related to weight gain, placental hormone production, increased fetal burden and increased food intake. Maternal islets adapt to this increased demand mainly through enhanced insulin secretion per β cell and increased β-cell proliferation [Retnakaran et al. 2008].

In 1994, a study was conducted by Jacobs and colleagues where 27 pregnant women with 1 or more risk factors for gestational diabetes had an intravenous β-cell stimulation test. Glucose, connecting peptide (C-peptide) and insulin levels were measured at baseline, 5, 10 and 15 min after the administration of 1 mg glucagon. It was shown that reduced β-cell function is found in women with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes during pregnancy [Jacobs et al. 1994; Buchanan and Xiang, 2005]. Another study assessed the change in insulin resistance and β-cell function in a multiethnic population-based cohort of pregnant women [Mørkrid et al. 2012]. The increase in insulin resistance was similar across the ethnic groups. However, the increase in β-cell function was significantly lower in East and South Asians compared with Western Europeans.

Adiponectin and leptin in GDM

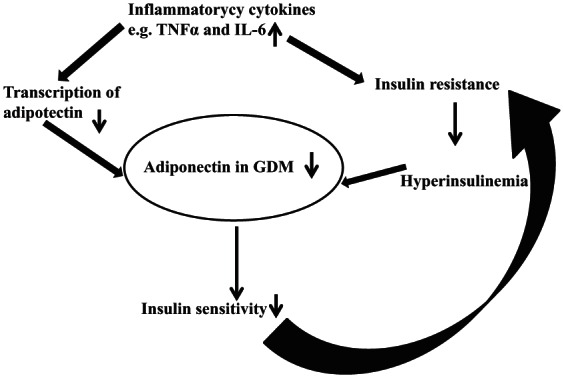

Adiponectin, a protein derived from adipose tissue, is thought to play a role in the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism [Buchanan and Xiang, 2005]. It exhibits insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory properties [Kinalski et al. 2005]. Serum adiponectin levels are decreased in obese individuals, as well as in those with insulin resistance or T2DM [Desoye and Hauguel-de Mouzon, 2007; Zaretsky et al. 2004]. Adiponectin exhibits progressive decline during pregnancy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Demonstrating the role of adiponectin in gestational diabetes.

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IL-6, interleukin 6; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor-α.

A case-control study by Meller and colleagues showed that women with GDM are more likely to have higher leptin mRNA expression in maternal-side placental tissue than normal controls. In addition, all leptin and adiponectin receptor isoforms had similar gene expression in cases and controls. These results suggest that GDM may be associated with changes in ligand expression, but not receptor expression in the placenta. Studies on adiponectin levels in GDM placental tissue are critical to determine whether this observation can also be applied to the adiponectin pathway [Meller et al. 2006].

In a cross-sectional study conducted between May 2007 and January 2009 by Skvarca and colleagues, adiponectin and leptin concentrations were measured in pregnant women. Insulin resistance was assessed using the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). The results showed that there was a significant correlation between the HOMA-IR and leptin concentration, but not between the HOMA-IR and adiponectin concentration. There was a significant inverse correlation between the HOMA-IR and adiponectin/leptin ratio [Skvarca et al. 2013].

Another case-control study of 30 women conducted by Lappas and colleagues on the release and regulation of leptin, resistin and adiponectin showed that there is a differential release of leptin from fetal and maternal tissues obtained from women with GDM and normal pregnant women. The dysregulation of leptin metabolism and/or function in the placenta may be implicated in the pathogenesis of GDM. Resistin release is greatly affected by a variety of inflammatory mediators and hormones [Lappas et al. 2005].

Ballesteros and colleagues conducted a prospective analysis involving 212 pregnant women, [132 with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) and 80 with GDM] and their offspring. The purpose was to analyze the relationship between maternal adiponectin (mAdiponectin) and cord blood adiponectin (cbAdiponectin) multimeric forms [high molecular weight (HMW), medium molecular weight (MMW) and low molecular weight (LMW)]. Maternal blood was obtained in the early third trimester and cord blood was obtained at delivery. Total adiponectin and the multimeric forms of adiponectin were determined in cord blood and maternal serum. No differences in cbAdiponectin concentration or its multimeric forms were observed in the offspring of diabetic mothers compared with NGT mothers. The HMW to total adiponectin ratio was higher in cord blood than in maternal serum, whereas the MMW and LMW to total adiponectin ratio was lower. Cord blood total and HMW adiponectin levels were positively correlated with birth weight and ponderal index (PI) (ratio of body weight to length), whereas cord blood MMW adiponectin was negatively correlated with the PI. In addition, cbAdiponectin and its multimeric forms were correlated with mAdiponectin concentrations. The investigators concluded that adiponectin multimeric distribution is not different in the offspring of GDM versus NGT mothers. Also, total adiponectin circulating levels and multimeric forms of adiponectin in cord blood are independently related to PI and multimeric forms of mAdiponectin, suggesting a crosstalk between mAdiponectin levels and fetal adiponectin production [Ballesteros et al. 2011]. Several other studies have been conducted about the role of adiponectin in GDM showing that hypoadiponectinemia is associated with both insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. As such, adiponectin emerges as an important factor potentially linking insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction in the pathogenesis of T2DM [Retnakaran et al. 2004, 2005; Ballesteros et al. 2011; Doruk et al. 2014].

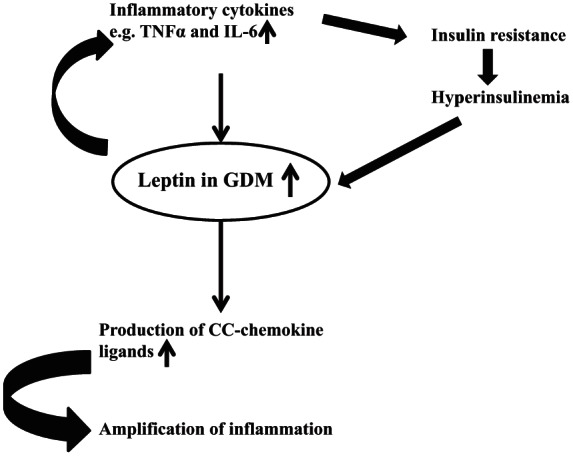

Leptin, which plays a key role in the regulation of energy intake and energy expenditure, is involved in a number of physiological processes including regulation of endocrine function, inflammation, immune response, reproduction and angiogenesis. Thus, leptin increases insulin sensitivity by influencing insulin secretion, glucose utilization, glycogen synthesis and fatty acid metabolism. Furthermore, leptin regulates gonadotrophin releasing hormone secretion from the hypothalamus and activates the sympathetic nervous system. It is transported across the blood–brain barrier where it binds to specific receptors of appetite modulating neurons, most notably in the arcuate nucleus. In normal pregnancy, leptin is 2–3 fold higher compared with the nonpregnant state with a peak at around 28 weeks of gestation. It has a potential role in implantation, induction of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) production in trophoblastic cells and regulation of placental growth. It also increases mitogenesis and stimulation of amino acid uptake. Compared with normal pregnant women, placental leptin expression in patients with GDM is increased. Conversely, leptin itself increases production of TNF-α and interleukin 6 (IL-6) by monocytes and stimulates the production of CC-chemokine ligands. Therefore, a vicious circle develops aggravating the inflammatory situation. Chronic insulin administration increases leptin secretion by adipocytes. Consequently, hyperinsulinemia in GDM might further stimulate leptin production (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Demonstrating the role of leptin in gestational diabetes.

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IL-6, interleukin 6; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor-α.

Placental versus maternal tissues role in GDM

The placenta is a source and a target for cytokines at the same time. The type and the location of the cytokine receptors present on the placental cells will determine whether signals are generated by placentally (internal), maternally (presumably adipose-derived) or fetally derived cytokines. This emphasizes the possibility of an external control of placental function that can become dysregulated when the cytokine levels are augmented, such as in GDM or obesity [Soheilykhah et al. 2011; Kinalski et al. 2005].

It would be difficult to differentiate the relative contribution of placental versus maternal tissues for regulation through TNF-α, leptin or resistin. The influence of adiponectin is exclusively of maternal origin due to absence of ligand but expression of adiponectin receptors in the placenta. There is now clear evidence that placental leptin is poorly released into the fetal circulation and that leptin synthesized by fetal adipose tissue can be taken as a marker of fetal adiposity [Desoye and Hauguel-de Mouzon, 2007]. Some of the stimuli that disturb placental metabolism may be also conveyed through the vascular endothelium (such as oxidative stress, endothelial injury, etc), hence, bringing into the picture influence from the fetus, through alterations induced by circulating fetal TNF-α, leptin, and IL-1 and IL-6.

Thus, the maternal–fetal control of the placenta is a cumulative result of cell cooperation that may propagate a vicious cycle for enhancement of cytokine production. This eventually may have an impact on insulin action in the fetoplacental unit and possibly cause obesity in utero. The discovery that the placenta produces some adipokines opens novel perspectives for understanding the specificity of pregnancy-induced insulin resistance. It also emphasizes the importance of functional interplay between the placenta and maternal white adipose tissue in GDM. Signals that regulate the secretion of these molecules are far from clear. Further studies in this area may provide a clue for understanding the inflammatory processes in GDM and obesity, and potentially in utero programming of obesity [Retnakaran et al. 2008; Zaretsky et al. 2004; Wolf et al. 2000].

Role of other adipokines

Regarding other adipokines, a review published by Miehle and colleagues in 2012 addressed the physiological role of the novel adipokines resistin, visfatin, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) and vaspin in GDM [Miehle et al. 2012]. However, the physiological significance of these adipokines in this entity is preliminary and remains far from clear [Stepan et al. 2010; Masuyama et al. 2011, Georgiou et al. 2008].

An overview of publications on the role of adipokines and β-cell dysfunction in GDM is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of publications on the role of adipokines and β-cell dysfunction in gestational diabetes.

| Authors | Number of subjects (n) | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Retnakaran et al. [2005] | 180 | • Adiponectin concentration is an independent correlate of β-cell function in late pregnancy. • Adiponectin may play a key role in insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. |

| Jacobs et al. [1994] | 27 | • Gradually decreasing insulin secretion from normal to subnormal without and with glucose intolerance, and diabetes mellitus |

| Soheilykhah et al. [2011] | 82 | • Serum leptin level is higher in GDM. • Serum leptin has a positive correlation with insulin resistance. • High leptin levels might be a risk factor for GDM and IGT. |

| Meller et al. [2006] | 47 | • Leptin mRNA expression in term placenta, but not its receptors, is associated with diagnosis of GDM. |

| Skvarca et al. [2013] | 74 | • The adiponectin/leptin ratio inversely correlates with HOMA-IR in pregnancy. |

| Lappas et al. [2005] | 30 | • Dysregulation of leptin metabolism and/or function in the placenta • Resistin release is greatly affected by a variety of inflammatory mediators and hormones. |

| Retnakaran et al. [2004] | 180 | • Decreased adiponectin levels in GDM compared with IGT or NGT in pregnancy • Adiponectin in pregnancy is strongly correlated with insulin resistance. |

| Ballesteros et al. [2011] | 212 | • Cord blood adiponectin concentrations are independently related to maternal adiponectin levels and unrelated to the diagnosis of GDM. • Maternal multimeric forms of adiponectin are independent predictors of the concentrations of cord blood adiponectin and its multimeric forms at delivery. |

| Doruk et al. [2014] | 88 | • Serum adiponectin levels are reduced which may have a role in the pathogenesis of GDM. • Alterations in the glucose metabolism may affect circulating adiponectin levels. |

| Kautzky-Willer et al. [2001] | 55 | • Higher plasma leptin concentrations in insulin-resistant GDM women during pregnancy and postpartum, compared to pregnant hyperglycemic women with type I diabetes and healthy women, despite similar pre-gestational weight. • Hyperleptinemia might be a marker of a latent metabolic syndrome. |

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NGT, normal glucose tolerance.

Conclusion

GDM develops when the pancreatic β-cell reserve is not sufficient to compensate for decreased insulin sensitivity during pregnancy. Most studies have found that hyperleptinemia in early pregnancy appears to be predictive of an increased risk to develop GDM later in pregnancy, independent of maternal adiposity. Circulating adiponectin levels are reduced in patients with GDM compared with pregnant controls independent of prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) and insulin sensitivity.

Considerable work is needed to explore the various mechanisms underlying maternal GDM and its evolution to diabetes after pregnancy. Genetic studies may help identify women whose β cells will tolerate insulin resistance poorly, as well as women who develop poor insulin secretion for reasons unrelated to insulin resistance. GDM is an especially attractive target for such studies because the disease is detected in the course of routine clinical care. This will provide an opportunity to study relatively early stages of glucose dysregulation that may be fundamental to the long-term pathobiology of diabetes. Future studies are needed to assess, in more detail, whether or not dysregulation of the newer adipokines directly contributes to the pathophysiology of GDM. Their role in predicting pregnancy complications could also be assessed. Finally, prospective long-term studies of sufficient size in patients with GDM need to be performed.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest in preparing this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Marwa R. Al-Badri, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, American University of Beirut-Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Mira S. Zantout, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, American University of Beirut-Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Sami T. Azar, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, American University of Beirut-Medical Center, 3 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, 8th floor, New York, NY 10017, USA

References

- Ballesteros M., Simón I., Vendrell J., Ceperuelo-Mallafré V., Miralles R., et al. (2011) Maternal and cord blood adiponectin multimeric forms in gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective analysis. Diabetes Care 34: 2418–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T., Xiang A. (2005) Gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 115: 485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desoye G., Hauguel-de Mouzon S. (2007) The human placenta in gestational diabetes mellitus. The insulin and cytokine network. Diabetes Care 30(Suppl. 2): S120–S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doruk M., Uğur M., Oruç A., Demirel N., Yildiz Y. (2014) Serum adiponectin in gestational diabetes and its relation to pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol 34: 471–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou H., Lappas M., Georgiou G., Marita A., Bryant V., Hiscock R., et al. (2008) Screening for biomarkers predictive of gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 45: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M., Verhoog S., van der Linden W., Huisman W., Wallenburg H., Weber R. (1994) Glucagon stimulation test: assessment of beta-cell function in gestational diabetes mellitus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 56: 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautzky-Willer A., Pacini G., Tura A., Bieglmayer C., Schneider B., Ludvik B., et al. (2001) Increased plasma leptin in gestational diabetes. Diabetologia 44: 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinalski M., Telejko B., Kuźmicki M., Kretowski A., Kinalska I. (2005) Tumor necrosis factor alpha system and plasma adiponectin concentration in women with gestational diabetes. Horm Metab Res 37: 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappas M., Yee K., Permezel M., Rice G. (2005) Release and regulation of leptin, resistin and adiponectin from human placenta, fetal membranes, and maternal adipose tissue and skeletal muscle from normal and gestational diabetes mellitus-complicated pregnancies. J Endocrinol 186: 457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama H., Inoue S., Hiramatsu Y. (2011) Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in preeclampsia. Endocrinol J 58: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller M., Qiu C., Vadachkoria S., Abetew D., Luthy D., Williams M. (2006) Changes in placental adipocytokine gene expression associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Physiol Res 55: 501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehle K., Stepan H., Fasshauer M. (2012) Leptin, adiponectin and other adipokines in gestational diabetes mellitus and pre-eclampsia. Clin Endocrinol 76: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørkrid K., Jenum A., Sletner L., Vårdal M., Waage C., Nakstad B., et al. (2012) Failure to increase insulin secretory capacity during pregnancy-induced insulin resistance is associated with ethnicity and gestational diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol 167: 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retnakaran R., Hanley A., Raif N., Connelly P., Sermer M., Zinman B. (2004) Reduced adiponectin concentration in women with gestational diabetes: a potential factor in progression to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 799–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retnakaran R., Hanley A., Raif N., Hirning C., Connelly P., Sermer M., et al. (2005) Adiponectin and beta cell dysfunction in gestational diabetes: pathophysiological implications. Diabetologia 48: 993–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retnakaran R., Shen S., Hanley A., Vuksan V., Hamilton J., Zinman B. (2008) Hyperbolic relationship between insulin secretion and sensitivity on oral glucose tolerance test. Obesity 16: 1901–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skvarca A., Tomazic M., Blagus R., Krhin B., Janez A. (2013) Adiponectin/leptin ratio and insulin resistance in pregnancy. J Int Med Res 41: 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soheilykhah S., Mojibian M., Rahimi-Saghand S., Rashidi M., Hadinedoushan H. (2011) Maternal serum leptin concentration in gestational diabetes. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 50: 149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepan H., Kralisch S., Klostermann K., Schrey S., Reisenbüchler C., Verlohren M., et al. (2010) Preliminary report: circulating levels of the adipokine vaspin in gestational diabetes mellitus and preeclampsia. Metabolism 59: 1054–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf H., Ebenbichler C., Huter O., Bodner J., Lechleitner M., Föger B., et al. (2000) Fetal leptin and insulin levels only correlate inlarge-for-gestational age infants. Eur J Endocrinol 142: 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaretsky M., Alexander J., Byrd W., Bawdon R. (2004) Transfer of inflammatory cytokines across the placenta. Obstet Gynecol 103: 546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]