Abstract

Participation in home-delivered meals programs may contribute to the health and independence of older adults living in the community, especially those who are food insecure or those who are making transitions from acute, subacute, and chronic care settings to the home. The purpose of this study was to conduct a comprehensive and systematic review of ALL studies related to home-delivered meals in order to shed light on the state of the science. A complete review of articles appearing in PubMed using the Keyword “Meal” was conducted; and titles, abstracts, and full-texts were screened for relevance. Included in this review are 80 articles. Most studies are descriptive and do not report on outcomes. Frequently reported outcomes included nutritional status based upon self-reported dietary intake. Additionally, most studies included in this review are cross-sectional, have a small sample size, and/or are limited to a particular setting or participant population. More rigorous research is needed to: 1) gain insight into why so few eligible older adults access home-delivered meals programs, 2) support expansion of home-delivered meals to all eligible older adults, 3) better identify what home-delivered meals models alone and in combination with other services works best and for whom, and 4) better target home-delivered meals programs where and when resources are scarce.

INTRODUCTION

Participation in home-delivered meals programs may contribute to the health and independence of older adults living in the community, especially those who are food insecure or those who are making transitions from acute, subacute, and chronic care settings to the home (1). The anticipated growth in the number of older adults, including many of whom are frail, homebound, and living alone, will likely increase the demand for nutritional and social services that enable seniors to remain residing in their own homes. Unfortunately, home-delivered meals programs are fragmented and poorly integrated with other services, are not available for many persons with the greatest needs, and are most often not reimbursed by either Medicare or Medicaid (2). Additionally, such programs are not without costs. The extent to which nutritional services, and specifically home-delivered meals programs, achieve their varied goals in a cost-effective manner is uncertain. The purpose of this paper is to comprehensively and systematically review the evidence on whether participation in a home-delivered meals program improves outcomes for older adults and whether these programs provide value proportionate to costs.

History and Definition of Home-delivered Meals in the United States of America

The earliest reported formal home-delivered meals programs originated in Great Britain during World War II when The Women’s Volunteer Service for Civil Defense delivered home-cooked meals to service personnel and civilians whose homes had been destroyed by bombs (3). Because the meals were often delivered in baby carriages, the moniker “meals-on-wheels” was applied and still refers generically to home-delivered meals programs throughout the world. The earliest reported home-delivered meals program originating in the United States began in 1954 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by Margaret Toy (a community activist and the first Director of the Meals on Wheels Program) and a group she organized, the “Platter Angels”, who delivered warm suppers to “homebound” people in need during a particularly harsh winter. Some British students, who were coincidentally studying social work at the community center where Mrs. Toy volunteered, recognized the similarities between the British and American efforts and the label “Meals on Wheels” was formally and indelibly attached to the US program. Over the next two decades, additional neighborhood Meals on Wheels programs sprang up across the country (4). These were largely organized by volunteers and supported by charitable institutions (with modest fees charged to those who could afford the cost of the food and preparation). Such programs, mostly not-for-profit, still exist today and many programs with broader missions provide varying home-delivered foodstuffs and/or meals to those determined by various criteria to be in need.

Home-delivered Nutrition Services Established by the Older Americans Act

The Older Americans Act (OAA) of 1965 provided the impetus for a wide variety of programs and services specifically developed for older adults and supported by federal tax dollars (See Lloyd and Wellman, 2015 and the US DHHS Administration for Community Living website for a comprehensive overview of these programs.) (5, 6). Nutrition services represent a major component of the OAA, especially with the establishment of congregate meals in the initial legislation and the addition of home-delivered meals in the late seventies. Home-delivered meals are intended for older adults who are considered homebound due to illness or disability and who are food insecure due to limitations in their abilities to procure and prepare food on a daily basis. Many recipients of home-delivered meals have multiple chronic health conditions and are often at nutritional risk. Meals may be delivered in a variety of forms including hot, cold, frozen, dried, canned, or shelf-stable. In rural parts of the country or areas that are difficult to access, there is an option for delivering a week’s supply of frozen meals. The home-delivered meals program is dependent upon volunteers to deliver meals and waiting lists can be long; consequently, not all persons (some of whom may be most vulnerable and living in urban areas perceived to have high crime rates) may not have access to services (7). It is estimated that less than five percent of eligible older Americans receive meals; and, on average, they receive less than three meals per week (8).

Recent Health Policy Initiatives Involving Home-delivered Meals

Changes in health care policies related to Medicare and Medicaid over the past couple of decades have major implications for older adults and home-delivered meals programs that may benefit them. Three are most notable. First, a steady shift upward in enrollment from the Original Medicare plan to Medicare Advantage plans has taken place since 2005 with 30% of enrollees now opting for private insurance instead of the traditional fee-for-service option (Medicare Advantage Fact Sheet, 2014) (9). One premium service provided by some insurers that is attractive to potential consumers is home-delivered meals following a hospitalization. Second, and more significant, a major shift involves the increasing rebalancing in long-term care taking place across the nation that enables older adults to remain in their homes and communities rather than enter a nursing home (10). Medicaid programs that provide home and community-based services as part of an array of long-term care services within the community may provide meals as part of those services. Last, and most significant, involves passage of Section 3025 of the Affordable Care Act, establishing the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program effective October 1, 2012 (11). This act reduces payments to hospitals that have excess readmissions. In response, hospitals throughout the nation are implementing many and varied hospital-to-home transition programs, some of which include home-delivered meals, in efforts to reduce “avoidable” readmissions. Not unexpectedly and concomitant with these policy changes, private for-profit companies such as Mom’s Meals (http://www.momsmeals.com/), which provides frozen nutritious and medical meals to patients, have emerged to meet anticipated demand for home-delivered meals.

What Outcomes Might We Expect From Participation in Home-Delivered Meals Programs?

An obvious outcome to consider is food and nutrient intake. Zhu and An recently conducted a systematic review focused on the impact of home-delivered meal programs on diet and nutrition among older adults (8). Based upon the inclusion criteria of their review, they were able to identify only eight studies that were of sufficient quality to include in their analysis. Zhu and An reported that six of eight studies found that home-delivered meals significantly improved diet quality, nutrient intake, and reduced food insecurity and nutritional risk among participants. All studies included in their review relied upon self-reported dietary intake. Self-report measures of dietary intake are increasingly considered an inadequate basis for making scientific conclusions because of their questionable validity and reliability (12). Fortunately, there are other outcomes that are useful to consider.

While not all home-delivered meal programs are targeted to explicitly address medical or clinical needs, it is reasonable to conceive of home-delivered meals as a “health service” where it is also reasonable to anticipate that health benefits might be conferred to recipients of those services. Donabedian presents a conceptual model to evaluate health services and quality of care by focusing on structures, processes, and outcomes (13). This review is driven by the research that has been conducted thus far and focuses largely on evaluating the “outcomes” of home-delivered meals from the clients’ perspective. Potential patient-centered outcomes of this evaluation include what are often called the 6 Ds of generic outcomes measures: death, disease, disability, discomfort, dissatisfaction, and destitution or dollars expended for health services (14). Home-delivered meals may be beneficial in many ways including improvements in nutrition and quality of life as well as reducing mortality, symptoms of a variety of illnesses, need for home health services, nursing home placement, and hospital admissions and readmissions. Additionally, from the perspective of the providers or payers of services, what is most frequently evaluated is cost. This review will cover this aspect of outcomes, also.

Why Is It Important to Study This Topic Now?

This review is necessary and timely given a number of recent trends. First, the rising proportion of older adults in the U.S., or the ‘Silver Tsunami,’ is a trend that is simultaneously changing the face of Americans and the programs designed to serve them. In 2010, there were an estimated 40 million adults over the age of 65 representing 13% of the population. By 2030, older adults are expected to comprise 20 percent of the population, with those 85 and older (the group more likely to require services) expected to grow more than any other age demographic (15). Second, the demand, as well as the costs, for home-delivered meals has increased. It is important to determine whether the benefits justify the costs and whether programs can be better targeted or improved upon to serve those most in need. While less than one-third of the cost is covered by federal programs, the remainder of the costs must be obtained from private and public funding sources. Reimbursement and payment sources are increasingly dependent upon evidence-based research that demonstrates improvements in patient centered outcomes. Health care policy is also adopting the trend of financial accountability of funded programs and requiring proof of effectiveness (See Thomas, 2015 in this issue for a discussion of these matters.) (16). Third, although home-delivered meals appear to be an appropriate solution for older adults who are often frail and nutritionally at risk, there are only scattered and limited studies testing efficacy and effectiveness. It is important to review existing evidence to determine how and to what extent home-delivered meals benefit their recipients.

The review conducted by Zhu and An had the following inclusion criteria: study design (randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, pre-post studies, or cross sectional studies); main outcome (food and nutrient intakes); population (home-delivered meal program participants); country (US); language (articles written in English); and article type (peer reviewed publications or theses) (8). As mentioned previously, only eight studies met their inclusion criteria and six of the eight found that home-delivered meals did improve diet quality, increase nutrient intake, reduce food insecurity, or reduce nutritional risk among participants. No restrictions were placed upon year of study. Eight studies meeting the inclusion criteria since 1965 when the OAA was passed represents a bleak state of the evidence regarding outcomes research of home-delivered meals programs. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to conduct a comprehensive review of ALL studies related to home-delivered meals that will shed light on the state of the science.

METHODOLOGY

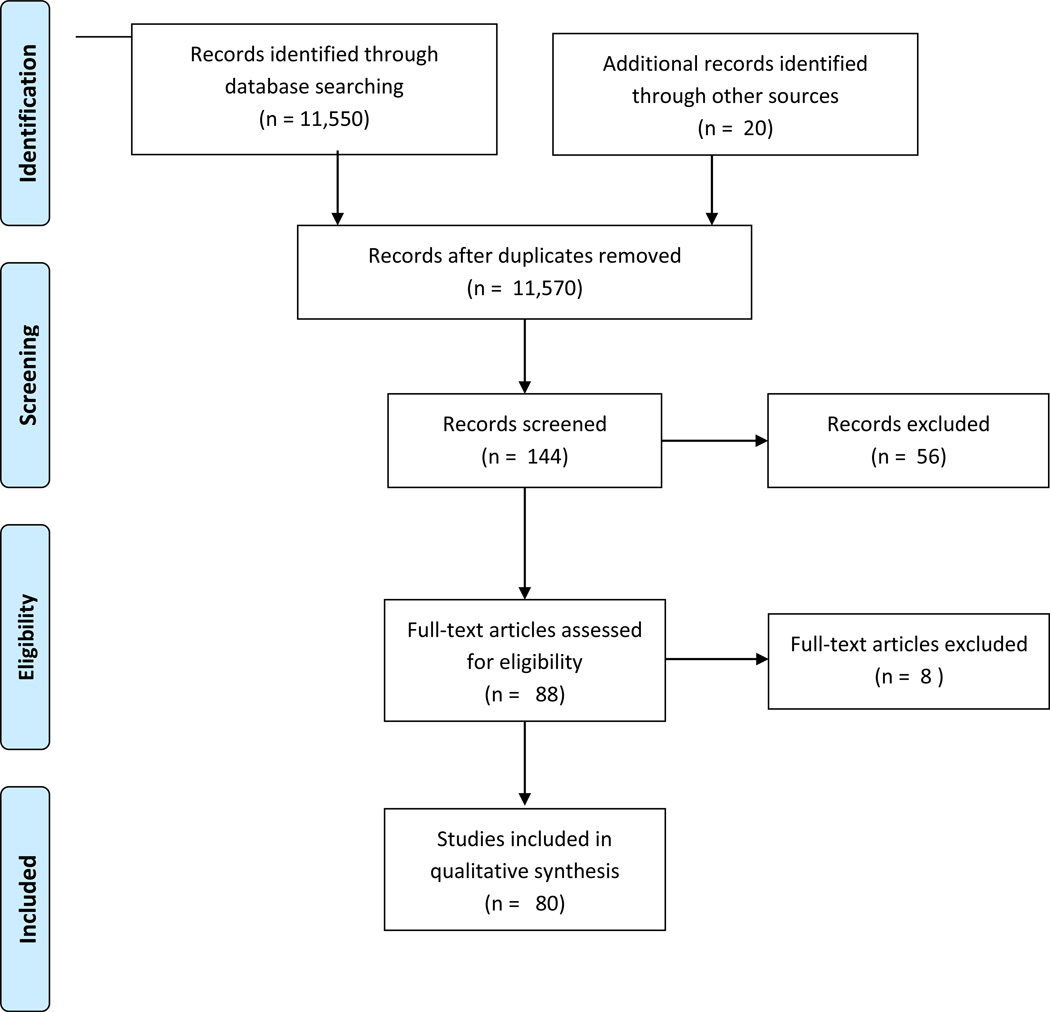

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement has been followed where applicable, including a flowchart of the study selection process (Figure 1) (17).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Articles Identified and Included.

In the winter of 2014–2015, a computer-based search of PubMed was conducted. Because there were so few articles identified using more restrictive terms (i.e., home-delivered meal, Meals on Wheels, etc.), one search term, “meal” was used to identify articles relating to home-delivered meals. The review was restricted to the age groups Middle Aged: 45–64 and Aged: 65+. Middle Aged was included because the OAA serves persons 60 years and older and other home-delivered meals programs also serve adult populations younger than age 65.

This systematic and comprehensive search included original empirical studies published at any time. Studies must have met the following criteria: (1) peer-reviewed or dissertation thesis, (2) written in or translated to English, (3) examine some aspect of home-delivered meals and any outcome (defined broadly). Studies were also included if home-delivered meals was used as an outcome. Both national and international studies were included in the search.

The relevance of titles and abstracts were independently assessed for review by the last author (JL). Next, relevant abstracts were independently assessed by the first (AC) and second author (AG); the third author (DB) was consulted when ambiguity arose. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus or by case review with all authors. The primary reasons for studies being excluded in the review were that there was no mention of “home-delivered” meals. The first (AC) and second (AG) authors retrieved all articles and reviewed the full text for data that was extracted and synthesized in this review, including author, year, design, sample and setting, outcome measures, and findings. The last author (JL) reviewed articles where methods were not clear. We did not exclude any papers because of poor quality because we wanted readers to gain a full appreciation of the totality of the research that has been conducted to date.

FINDINGS

Figure 1 details the literature search and selection process. After applying the inclusion restrictions to the title and abstract search for meal, 11,550 studies remained for abstract review. Upon title/abstract review, 144 full-text articles were screened further (including seven data-based articles appearing in this special issue and 13 articles identified through other sources). Sixty-four articles were excluded based upon more complete text assessment. The total number of papers included in this qualitative descriptive synthesis is 80.

Table 1 provides a summary of the 80 articles listed first by study type (Cross-sectional descriptive studies of older adults receiving home-delivered meals; Cross-sectional descriptive studies of older adults comparing those receiving home-delivered meals with those who are not [receipt of home-delivered meals is the primary comparator]; Cross-sectional descriptive studies of older adults comparing those receiving home-delivered meals with some other group; Pre- post-assessment of home-delivered meals; Longitudinal studies examining patterns, predictors, and outcomes related to home-delivered meal service utilization; Non-randomized interventions involving home-delivered meals; Randomized controlled trials involving home-delivered meals; Quasi-experimental design studies using receipt of home-delivered meals as the intervention; and Evaluation of impact of home-delivered meals using administrative claims data, state program reports, or surveys of providers).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies evaluating some aspect of home-delivered meals.

| Source | Study Design | Setting and Sample | Outcome Measure | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional Descriptive Studies of Older Adults Receiving Home-delivered Meals | ||||

| Frongillo et al. 2010 (18) | Random telephone survey | 1,505 MOW recipients in New York City | Food preparation methods and eating behavior | 13.6% of participants relied solely on MOW meals. Of those who consumed non-MOW foods, 66.2% prepared it themselves; 35.8% shop for non-MOW foods themselves. The rest are assisted by relatives or home attendants. |

| Frongillo et al. 2010 (19) | Random telephone survey | 1505 HDM recipients in New York City participated in the first survey. A second survey was conducted with 500 recipients. | Adequacy and satisfaction with delivery of services and use of meal services | About 75% of recipients reported satisfaction with meals and delivery. Most satisfaction came from those who were food secure, emotionally stable, religious, and had social support. |

| Timonen and O’Dwyer 2010 (20) | Face-to face interviews | 63 participants in Irish MOW service interviewed in their homes | Social contact, regularizing of mealtimes, and acceptance of service | Meals recipients derived limited social contact from the service; regularising mealtimes was not important to most recipients; and many were reluctant to accept the service. |

| Choi et al (2010) (21) | Face-to-face or telephone surveys | 736 MOW clients in central Texas | Depressive symptoms assessed with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | 17.5% of MOW clients had clinically significant depressive symptoms. 8.8% had probable major depressive disorder. The multivariate regression results show that age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, cognitive impairment, number of chronic medical conditions, and the nutritional risk score were significant predictors of the severity of depression symptoms. |

| O’Dwyer et al. 2009 (22) | Face-to face interviews | 63 participants in Irish MOW service interviewed in their homes | Nutritional status as measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) Typical daily intake per 24-hour dietary recall | 38.5 % of recipients were malnourished or at nutritional risk and 52.3% were overweight or obese. Mean kcalories was only 35–40% of the RDA for men and 42–45% of the RDA for women. Vitamin C, D, folate and calcium were below 1/3 of RDA. |

| Lirette et al. 2008 (23) | Self-administered survey | 271 clients from a MOW program in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada | Satisfaction and preferences | 72–88% of hot meal clients were satisfied with meal components. 99% would refer a friend to the program. |

| Duerr 2006 (24) | National Current Population Survey-Food Security Survey Module Telephone Survey | 143 West Central Indiana community-dwelling older adults (ages 60+) participating in home-delivered meals programs | Food security status | 74.8% were food secure (lower than the 94% national rate). Gender and age were significant predictors of food security. |

| Parsons and Rolls (2004) (25) | In-home assessment and interview | 60 Clients of Maimonides Geriatric Centre Meals on Wheels program in Montreal, Quebec | Food and eating behaviors related to receipt of home-delivered meals | Upon receiving the meal, 89% did not eat it immediately. Those who ate the meal later stored it in the refrigerator. All had some appliance available to heat the delivered meal; 55% used a microwave. Approximately 75% did not object to receiving meals chilled. Most delayed consuming the meal until later in the day. |

| Sharkey 2004 (26) | Chart review of data obtained by meals program staff | 908 homebound Mexican American and non-Mexican American elders (ages 60+) in the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley who receive OAANP home-delivered meals | Nutritional risk | Mexican Americans were more likely to report poverty, nutritional risk factors, and indicators of poor nutritional health than non-Mexican Americans. |

| Sharkey 2003 (27) | Face-to-face interviews from the Nutrition and Function Study | 279 homebound older women (ages 60+) who received regular home delivered meal service in four North Carolina counties | Three categories of food sufficiency status (food sufficient, risk of food insufficiency, and food insufficient) | Food insufficient women were more likely to report multiple morbidity burden. Women at risk reported lower intakes of multiple nutrients. |

| Krondl et al. 2003 (28) | Telephone interviews and seven-day food records | 137 elderly home delivered meal recipients (90 F/47 M) ages 75+ in Ontario, Canada | Nutritional risk factors of living situation, functionality, morbidity, and medication use | Probability of nutritional risk was highest for calcium, Mg, zinc, and folate. Risk was more pronounced for women. |

| Sharkey et al. 2002 (29) | In-home interview and assessment and three 24-hr dietary recalls | 354 cognitively eligible recipients of home delivered meals in North Carolina | Nutritional risk (measured by the DETERMINE checklist) and increased severity of disability (measured by a modified version of the Activities of Daily Living Scale) | Lower intakes of specific nutrients were associated with being a woman, black, and reporting a low income and lower education, and reporting not usually eating breakfast. Key inadequate nutrients were calcium and vitamin D. |

| Sharkey and Schoenberg 2002 (30) | Chart review of meals program participants | 729 black and white older women (ages 60 to 74) receiving home delivered meals in Wake County, North Carolina | Nutritional Health Index, Functional disability | Moderately high and very high levels of nutritional risk were associated with being black, having an income less than or equal to 125% of the poverty level, living alone, and being in the age range of 60–74 years. |

| Sharkey 2002 (31) | Chart review of meals program participants | 1,010 home-delivered meals program participants in Wake County, North Carolina | Relationship between individual components of nutritional risk and increased severity of disability | Association of nutritional risk and increased disability was associated with unintended weight change and medication use. |

| Millen et al. 2002 (32) | Face-to-face interviews | Nationally representative sample of ENP participants who received congregate (1,040) and home delivered meals (818) | Nutrient intake (estimated from the Nutrient Data System based on dietary recall interviews) and socialization patterns (measured by average monthly social contacts) | ENP is provided to about 7% of the overall older population. ENP participants are better nourished (4 to 31% higher mean daily nutrient intake) than non-participants. Participants achieve higher levels of socialization (17% higher) than non-participants. |

| Choi 1999 (33) | Record review from participants in a county MOW program | 509 MOW recipients ages 60+ in Western New York State | Reasons for elders termination from a MOW program | Reasons for termination of participation was largely associated with deteriorating health. More African American elders discontinued participating due to lack of satisfaction with meals or poor appetite. |

| Vailas et al. 1998 (34) | Self-administered survey | 155 participants ages 60+ enrolled in the Title III-C meal program in Pepin County, Wisconsin (108 received meals at congregate sites and 47 received HDM) | Nutrition Screening Checklist (DETERMINE)Quality of life | Quality of life and quality of health were positively correlated. Nutritional risk, food insecurity, decreased enjoyment of food, depression, and impaired function were negatively associated with quality of life. |

| MacLellan 1997 (35) | In-home questionnaire, dietary assessment, and anthropometric measurement | 28 recipients of home-delivered meals in a small Canadian city | % contribution of the consumed portion of delivered meal to daily energy/nutrient intakes | Meals generally met recommended nutrient intake with the exception of energy, zinc, and vitamin A for men and zinc for women. |

| Coulston et al. 1996 (36) | Anthropometric assessment, dietary intake, and blood samples, and self-administered questionnaire | 230 MOW applicants (60–90 years old) free from terminal illness over a 2-year period | Poor nutritional status using anthropometric, dietary, lab data, and with a Nutrition Screening Initiative (NSI) self-assessment tool | 74% of MOW applicants were found to be at risk for poor nutritional status and 98% were at risk according to the NSI self- assessment tool. |

| Fogler-Levitt et al. 1996 (37) | Face-to-face interview | 137 white, independent living recipients of MOW 75+ years old (90F/47M) in southern Ontario, Canada representing both rural and urban settings | Meal utilization | Meal utilization ranged from 67%–83%. Levels for energy, 8 nutrients, and specific foods were higher for men than women. Women living alone showed higher utilization values for energy and 11 nutrients compared to those living with others. Age had no effect on utilization. |

| Herndon 1995 (38) | In-home survey, nutrition screening, and collection of anthropometric data | 130 clients receiving HDM in Lake County, Indiana | Nutritional health | 28% of participants found to be at no nutritional risk, 39% at moderate nutritional risk, and 33% at high risk from NSI. 68% of these clients could not function in their homes without delivered meals. |

| Long and Miller 1994 (39) | Mail survey | 592 elders (60+) receiving home delivered meals in a large, New York urban area and 50 elders in sub sample given oral examination | Oral status (oral function, dental problems, oral hygiene practices) and well-being | Oral status is positively correlated to well-being status. |

| Ellis and Roe 1993 (40) | Client records compared and 1980 U.S. census statistics | 2,238 clients across 6 countywide home-delivered meal programs in upstate New York ages 65+ | Poverty rates and population densities for community-residing individuals ages 65+ | Client participation levels were positively correlated with population densities but not with poverty rates. Impoverished and sparsely populated regions received minimal services. |

| Frongillo et al. 1992 (41) | In home interviews and a self-administered surveys | Interview of 4,017 HDM clients (ages 60+) in 1984–1986 before receiving meals, Self-administered survey in 1985–1986 of 2,648 congregate meals clients already receiving meals in 31 NY State counties | Not eating for 1+ days | Ethnicity, location, living situation, mobility, health status, loss of appetite, diarrhea, nausea, difficulty swallowing were positively related to not eating. 17.5% of HDM clients were not eating for 1 or more days. |

| Stevens et al. 1992 (42) | Face-to-face interviews and 3-day food records | Elderly clients receiving Title III-C HDM (ages 60–94) in Northern California, urban group – 48, Rural group – 47 | Nutrient intake | No significant nutrient intake differences were observed between groups, but both groups needed assistance with cooking and shopping for food and had intakes below 66% RDA for 3+ nutrients. |

| De Graaf et al. 1990 (43) | Face-to-face interview | Random sample of 124 older adult (65+) recipients of MOW living in a Dutch urban community | Perceived quality of meals, perceived quality of service, ADLs, subjective health, food habits, frequency of visits with social network | MOW recipients are not mobile, have low subjective health, and are not socially connected. Reliability was the primary factor associated with perceived quality. |

| Walden et al. 1988 (44) | Face-to-face interviews | 16 older adult HDM recipients (ages 65+) randomly selected from a local HDM provider | Dietary intakes of HDM recipients on a day they receive a meal and on a weekend day when they do not receive meals | Elderly HDM recipients more likely to have insufficient intake of protein, thiamine, riboflavin, calcium, iron, and phosphorus on weekends than weekdays when receiving 5 meals a week. |

| Cairns and Caggiula 1974 (45) | Mailed surveys | 174 MOW recipients across 5 programs in Pittsburgh, PA | Recipient satisfaction and attitude towards MOW | The majority of recipients were appreciative. In two programs, 20% got no socialization with deliverers. 3% said food was not eaten in one program, and 33% said food was not eaten in another program. |

| Williams and Smith 1959 (46) | Face-to-face interviews | 21 MOW recipients ages 65+ in Columbus, Ohio | Attitude and change in health or activity, need for changes in food serviced, needs for other types of services | Appreciation was expressed by recipients; some suggested larger portions. 15 reported having substantially better diets with MOW. |

| Cross-sectional Descriptive Studies of Older Adults Comparing Those Receiving Home-delivered Meals with Those Who Are Not (Receipt of Home-delivered Meals Is the Primary Comparator) | ||||

| Lee et al. 2015 (47) | Client records | Older Georgians receiving Older Americans Act Nutrition Program Services and other Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) using state aging administrative data (N=31,341) | Food insecurity, sociodemographic, economic, and functional characteristics | Those receiving HDM and other in-home and caregiving services were more likely to show poorer sociodemographic, economic, and functional characteristics, and food insecurity. Those receiving multiple HCBS were most vulnerable, but showed lower level of food insecurity than those receiving single HCBS suggesting potential combined benefits of receiving multiple programs. |

| Luscombe-Marsh et al. 2013 (48) | Face-to-face interviews | 250 older adults (ages 69+) in South Australia, three groups: poorly nourished receiving MOW, poorly nourished not receiving MOW, and well-nourished | Weight loss Hospital admissions | No significant differences were observed in weight loss between groups. Receiving MOW for those who were poorly nourished reduced the likelihood of having a hospital admission within 12 months. |

| Steele and Bryan 1985 (49) | Face-to-face interviews | 54 community-dwelling adults (60+) in North Carolina grouped by recipients and non-recipients of HDMs | Energy, carbohydrate, protein, lipids, vitamins, and minerals intake, Diet rating | Recipients had significantly lower intakes of carbohydrate, thiamin and iron. Only 22% of all participants had diets rated ‘good’ and 27% rated ‘poor’. Both recipients and non-recipients had fat intake higher than recommendations. |

| Williams 1980 (50) | Face-to-face interviews | Two groups: (1) 145 patients ages 65+ who had been receiving home help, meal services, or day care in the previous 2 months and (2) 149 patients ages 65+ not receiving services in Oxford, Great Britain | Severity of need for meal service | Severe need for services fell on those who were disabled, poor, widowed or single, and with few local relatives. |

| Cross-sectional Descriptive Studies of Older Adults Comparing Those Receiving Home-delivered Meals with Some Other Group | ||||

| DiMaria-Ghalili et al. 2015 (51) | Self-administered surveys of MANNA clients and OAA clients | 171 MANNA meal recipients from Philadelphia area who completed an Annual Satisfaction Survey in 2013 compared with 191,272 OAA recipients from the Northeast who completed National Survey of Older Americans Act Program in 2013 | Satisfaction and food security | MANNA recipients were more satisfied with the taste and variety of food, and rated program as excellent. MANNA recipients were more likely to report not having enough money to buy food, skipping meals because of money, needing to choose between food and medications or food and utilities. |

| Hong 2010 (52) | Face-to-face and telephone interviews from the 2004 National Long-Term Care Survey | 1,908 informal caregivers (ages 15–97) caring for disabled older adults ages 65+ in the U.S | Patterns of caregiver service utilization among informal caregivers of frail older adults | 11% of caregivers interviewed used HDM and those who used multiple services were more likely to use HDM. |

| Wallace et al. 2000 (53) | Analysis of existing client data | 1,816 low income and rural elderly women (ages 65+) in South Carolina receiving Area Agency on Aging services/ 1,138 white; 678 black | Utilization of community based services | The most often used services were: case management outreach, congregate meal, and home delivered meals. Age, payment source, income, sensory impairment, and function were associated with the number and type of services used, but these differed by race. Also white female elderly were more likely than black female elderly to use HDM (14% vs. 6%). |

| Chumbler et al. 1998 (54) | Face-to-face in-home interviews | 553 older adults (65+) living in rural Arkansas counties who were enrolled in a Medicaid waiver program (randomly selected) | Likelihood of receiving one of four types of in-home health and support services, including home-delivered meals | Living alone and needing assistance with ADLs significantly increased the likelihood of receiving HDM. Higher age was negatively associated with receiving meals. |

| Wallace and Hirst, 1996 (55) | Client records | 2,474 elders being served by a Regional Area Agency on Aging in South Carolina categorized into three age groups: 937 Young Old (ages 65–74), 1,070 Middle Old (ages 75–84), and 467 Old Old (ages 85+) | Differences in number, type, and predictors of community based service use | The services most frequently used were case management, congregate meal, HDM, outreach, and recreation. The young old group used the highest number of services; the old old group had lowest use of activity related services. |

| Webber et al. 1994 (56) | Medical records and face-to-face interviews with proxies using MUDS (minimum uniform data set) instrument at 9 California ADDTCs (Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers) | 2,505 patients from 9 Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers (479 living alone and 2,026 living with others) in California / all ages | Reliance on formal services | Living arrangement is a predictor of service utilization among persons with dementia. Those living alone are less likely to use HDM than those living with others (16.7% vs. 6.2%). |

| Pre- Post Assessment of Home-delivered Meals Program | ||||

| Vaudin and Sahyoun 2015 (57) | Face-to-face in-home surveys conducted at baseline (within 2 weeks post-hospital discharge) and 2-months post from the Community Connections Demonstration Project | Participants enrolled in home-delivered meals program in six states following a hospitalization (n=566 at hospitalization and n=377 at post) | Food anxiety | Food anxiety was greater among Hispanics, smokers, diabetics, and those who ate alone or had difficulty cooking. Food anxiety was lower at follow-up. |

| Wright et al. 2015 (58) | Telephone interview pre- and post MOW program participation | 62 Meals on Wheels clients from Central Florida aged 55+ | Nutritional status, dietary intake, well-being, loneliness, and food security | Improvements were observed for nutritional status, dietary intake, food security, loneliness, and well-being. |

| Marceaux 2012 (59) | Face-to-face in-home interviews upon MOW enrollment and 3-month follow-up | 47 newly enrolled MOW participants over 65 in Texas and 40 completed and 40 follow-up. | Nutrition status measured by the Nutrition Screening Initative checklist and the MNA-SF Nutritional intake measured by the Food Frequency Questionnaire | Significant improvements in nutrition status between baseline and 3 months were observed. Significant decreases in intakes of vitamin D, fats, and % calories from sweets were observed. Increases in beta-carotene and % calories from protein were observed. |

| Frongillo and Wolfe 2010 (60) | Face-to-face interviews and in-home assessments collected prior to receiving services, at 6 months, and 12 months | 212 participants from three NY counties who were referred for aging services (community-based long-term care services) / 171 received HDM and 41 received other services | Dietary patterns, Nutrition intake, Nutrient density, Level of food insecurity, Measured weight | Improvement in most dietary intake variables were observed in the HDM groups compared with the comparison group. The HDM group was less likely to be food insecure. HDM were more likely to impact those living alone with poorer initial status. |

| Sharkey 2005 (61) | In-person assessments and interview completed at baseline and 1-year follow-up | Random sample of 268 homebound older adults in NAFS (nutrition and function study) who regularly received home-delivered meals in North Carolina | Level of food sufficiency and risk | Food sufficiency status diminished over time; however it remained or became worse for those with diabetes. |

| Sharkey and Schoenberg 2005 (62) | In-person assessments and interview completed at baseline and 1-year follow-up | Random sample of 268 homebound older adults in NAFS (nutrition and function study) who regularly received home-delivered meals in North Carolina | Level of food sufficiency and risk | Lack of money for food was associated with increased risk and presence of food insufficiency. Increased odds of food insufficiency was observed among whites. |

| McAuley et al. 2005 (63) | Cohort design comparing baseline and intervention using telephone interviews | 180 homebound seniors at nutritional risk enrolled in the SENSE project (System to Enhance Nutrition Services for the Elderly – demonstration project to provide food, nutrition education, and social service case management through HDM) | Early withdraw from home-delivered meals program | Early withdrawal is related to participants who were more mobile, ate less often, and responded that food tastes good less often. |

| Edelman and Hughes 1990 (64) | Secondary analysis conducted on data obtained directly from clients using the self-administered MFAQ (multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire) | Homebound elderly persons at baseline, 9 months (225), and 48 months (76) after acceptance to community care and HDM programs in Chicago (ages 65+) | Informal care from family – use of services | Significant increase in amount of formal services provided to both groups was associated with a large proportion of new or supplementary services provided by agencies, but no significant decrease in amount of informal service provided were observed. There was a weak impact of formal service on informal care. |

| Frongillo et al. 1987 (65) | Telephone surveys at baseline to newly enrolled clients of HDMs from SNAP and at 6 months by local agency nutritionists | 2,002 elderly receiving HDMs in 23 counties of New York State (ages 60+) | Continuance of elderly on HDM programs | 37.4% of clients left program by follow up. Whites left programs at a rate of 2.6 times more than minorities. Many with cancer died and those who had not experienced fractures were more likely to leave programs. |

| Longitudinal Studies Examining Patterns, Predictors, and Outcomes Related to Home-delivered Meal Service Utilization | ||||

| An 2015 (66) | In-person and telephone interview from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2012 waves, within-individual variations in diet and service use status between 2 nonconsecutive 24-hour dietary recalls | 145 home-delivered meal service users identified in the NHANES data | Nutrient intake | HDM service use was associated with increases in daily intake of fiber, protein, calcium, copper, magnesium, potassium, selenium and sodium; but not total energy, fat and vitamin D. |

| Cho et al. 2015 (67) | Telephone interviews at 3 and 6 months | 121 patients recently discharged from an inpatient hospitalization or emergency department | Hospital readmission | Clients received 6.25 meals per week with meal delivery starting on average, 8.95 days post-discharge. Ninety-three of the 121 clients also elected to receive the HomeMeds program. Client self-report of hospital readmission at three months and six months was lower than expected given client characteristics |

| Sattler et al. 2015 (68) | Secondary data analysis using data from the Georgia Advanced Performance Outcomes Measures Project 6 (self-administered surveys of clients) merged with Medicare beneficiary and claims data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | 315 older Georgians participating in some OAA program who had at least 1 inpatient hospital admission in 2008 | Hospital readmission | (Re)admissions were significantly more likely in individuals who requested OAANP Home Delivered Meals. |

| Chen and Berkowitz 2012 (69) | Longitudinal study with baseline face-to-face interviews and two follow up telephone interviews as part of the Second Longitudinal Study of Aging | 3,085 US older adults (nationally representative) (70+) grouped according to 4 residential transition groups: (1) community-community-community, (2) community-institution-community, (3) community-community-institution, and (4) community-institution-institution | Use of home- and community-based services | Use and patterns of services differed slightly among the 4 groups. Different combinations of services were associated with different transitional directions. Older adults in the community-institution-institution group were more likely than other groups to use MOW. |

| Kim and Frongillo 2009 (70) | Data from two longitudinal studies were used: face-to-face in-home interviews plus telephone follow ups every other year from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS, 1996–2002) and the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD, 1995–2002) | 7,623 participants for HRS and 3,378 for AHEAD in USA ages 51+ | Participation in food assistance programs (FAP) | Older adults appeared to have persistent patterns between food insecurity and participation in FAP, especially in the Food Stamp Program. More persistently food-insecure older adults had higher participation in FAP. Food-insecure older adults at one time were more likely to shift from non-participation to participation in FAP the next time than food-secure older adults. Regardless of previous food insecurity status, previous participants in FAP were more likely to participate subsequently. |

| Keller 2006 (71) | In person interview at baseline and 18-month follow up phone interview | Cognitively well, vulnerable seniors in southwestern Ontario, Canada. 367 participated in baseline interviews and 263 completed follow up interview | Risk evaluation for Eating and Nutrition (SCREEN) questionnaire | MOW use and higher income was associated with higher SCREEN questionnaire scores (lower nutritional risk) at follow up. |

| Davies et al. 1981 (72) | Longitudinal study with a face-to-face dietary reassessment and 3-day food recall to compare with same assessments collected 10 years before | 100 elderly patients from the Gerontology Nutrition Unit in London considered to be at nutritional and/or social risk originally participated in a 1970 MOW survey; there were 7 traced survivors in 1980 (ages 75–90). | Dietary intake, socioeconomic situations | Traced subjects were maintaining their original energy and nutrient intakes, in spite of deteriorating health. Participants kept similar style and patterns of eating (no long gaps without food). |

| Non-Randomized Interventions Involving Home-delivered Meals | ||||

| Charlton et al. 2013 (73) | Single group, pre-post intervention testing addition of snacks 5×week in addition to regular MOW for 4 weeks | Convenience sample of 12 MOW clients in Australia | Nutritional status measured by MNA | Increased energy and protein intake, significant MNA score improvements, and decreased proportion of participants identified as malnourished or at risk of malnutrition was observed. |

| Galea et al. 2013 (74) | Case study of MOW ordering, food choices, and usage patterns through in-home interviews/dietary assessments | 12 MOW clients in Camden, New South Wales, Australia / (10 women, 2 men) | Nutritional status measured by MNA-SF / Dietary Diet history interview, 24-hr recall and food frequency questionnaire | Meal packages ordered by participants, on average, contributed 23.3% of daily energy and 34.1% of daily protein requirements. Meals meet daily dietary recommendations only if all meal components are ordered (main meal, soup, & dessert) |

| Wunderlich and Piemonte 2012 (75) | Two year intervention (CGM participants received classroom nutrition education and counseling / HDM participants received only handouts and phone counseling) | 355 participants (96 HDM and 259 CGM) in a northern New Jersey county (ages 60+) | Nutrition Survey Risk Screening questionnaire | Nutrition education and counseling improved nutrition risk scores (0.44 improvement in CGM and 2.0 improvement in HDM.) Slight improvements were observed in nutrition behaviors. |

| Watkins et al. 2012 (76) | Single group non-experimental study evaluating the effectiveness of a Hospital to Home program | 292 Medicare or Medicaid recipients 65 years and older in the Southeast U.S. who meet at least 2 out of 11 predictors for hospital readmission | Hospital readmission Quality-of-life scores (SF-36) | Hospital readmissions decreased by 61% for high risk population. 30% of participants received MOW. Significant improvements in quality-of-life scores were observed, and 99% respondents were satisfied with the Hospital to Home program. |

| Goeminne et al. 2012 (77) | Prospective cohort trial / data collected by subtracting weight at the end of the meal from the weight at serving time and face-to-face interviews | 106 Belgian hospitalized patients receiving MOW bedside versus 83 patients in control group | Average daily food intake Consumption of oral nutritional supplements Average daily food waste Food access and appreciation | MOW patients had significantly higher daily food intake, higher consumption of oral supplements, less waste, and reported greater food access and appreciation versus patients in control group. |

| Sahyoun et al. 2010 (78) | Face-to-face in-home surveys conducted at baseline (within 2 weeks post-hospital discharge) from the Community Connections Demonstration Project | 566 hospital-discharged participants (ages 60–96) in 6 US communities with HDM programs – participants put into 1 of 4 groups (2 groups enrolled in HDM within 48 hours of discharge, 2 enrolled in demonstration project 2 weeks post discharge) | Health and nutrition status, functional limitations, and depressive symptoms | More than 80% reported at least one limitation in daily living, 20% had impaired cognition, 40% had depressive symptoms, 40% reported fair or poor appetite. A larger percentage of demonstration project participants reported fair/poor health status and depressive symptoms. Early enrollees reported higher self-reported health and higher social support. |

| Gollub and Weddle 2004 (79) | Two group Comparison: (1) Breakfast group who received breakfast and lunch 5 days/week and (2) comparison group who received only lunch 5 days/week | Breakfast group: 167 and comparison group: 214 / participants recruited from 5 Elderly Nutrition Programs (south Texas, south Florida, western Montana, southwestern Virginia, and eastern Maine); most were low income and lived alone (ages 60–100) | Nutritional status, food security, depressive symptoms | Breakfast group participants had greater energy/nutrient intakes, greater levels of food security, and fewer depressive symptoms than comparison group. |

| Kretser et al. 2003 (80) | Comparative study of traditional MOW model (5 hot meals/week) and new model (3 meals and 2 snacks/7 days a week). Data collected at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months through in-home assessments and self-report | 203 adult (60+) MOW applicants in Mecklenberg County, NC | Nutritional status measured by the MNAADL and IADL | The new MOW group gained significantly more weight between each time point. MNA scores improved more rapidly in the new model. Functional change was associated with BMI and age than intervention. |

| Gleason et al. 2002 (81) | Single group intervention combining heart-healthy HDM and diet education with baseline, 4-wk, and 8-week measurements and interviews obtained | 35 community-dwelling adults aged 40–79 in the greater Boston area | Nutrient intake, weight, BMI, fasting serum lipid profiles, quality of life, and quality of diet questionnaires | Significant reductions were observed in weight, BMI, and cholesterol and improvements in quality of life and quality of diet at week 8. |

| Richard et al. 2000 (82) | Single group intervention where clients were invited to participate in at least four restaurant outings, Data collected on-site | 185 MOW clients who were invited to participate in at least four restaurant outings from two Montreal area districts | Participation in outings | ~Half of clients tried at least one outing, more than 25% participated in at least one third of outings. Clients were diverse. |

| Corson et al. 1989 (83) | Formal evaluation of basic case management model versus financial control model at 6, 12, and 18 months | Sample Sizes: basic model 1,630, 1,362, and 518 at 6, 12, and 18 months, respectively; financial model 1,785, 1,466, and 545/Location: Not determined | Effect of channeling (expanding available services) on access to formal community services, including receipt of HDM | Channeling achieved increases in-home care with the largest effects observed for personal care and homemaker services. Those in the financial control model were significantly more likely to receive HDM at all three time points. |

| Lipschitz et al. 1985 (84) | Intervention testing dietary supplement in addition to MOW with measurements obtained at baseline, 4, 8, and 16 weeks | 12 MOW recipients identified as being protein-calorie malnourished in Pulaski County, AR | Caloric intake and BMI | Substantial increases in protein intake and weight gain occurred following 16 weeks of supplementation. |

| Osteraas et al. 1983 (85) | Formal evaluation of alternative frozen meals system. Participants had an initial face-to-face interview followed by a phone interview (after 4–6 days) and a final face-to-face interview (after 20–35 days) | 31 participants (ages 65+) using the experimental meals system (which delivered frozen meals) in two Massachusetts cities | Client approval, effect of client’s social contacts, and cost efficiency | The alternative frozen meals system met clients’ acceptance, maintained usual social patterns, and produced a cost savings of 16%. |

| Randomized Controlled Trials Involving Home-delivered Meals | ||||

| Racine et al. 2012 (86) | Randomized control trial of home-delivered DASH meals and medical nutrition therapy Data collected at baseline, 6 months, 12 months | 298 adults aged >60 years with hypertension and/or hyperlipidemia in a southeastern North Carolina county | Change in BMI Energy Consumed Percent of energy needs consumed | Meals did not have a significant effect on any of the outcomes. Meals were significantly associated with a decrease in energy consumed for participants at or above the poverty threshold. |

| Noda et al. 2012 (87) | Randomized single-blind control trial of two groups with and without dietary counseling and consumption of an ordinary diet for 4 weeks then subdivitied ito two groups with and without dietary counseling and receiving calorie-controlled lunch and dinner boxes for four weeks/Self-adminstered questionnaires completed at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks | 200 adult patients (ages 22–72) with hypertension and/or diabetes in Fukuoka, Japan | Body weight Waist circumference Blood pressure Glycoalbumin | Significant reductions in outcome measures were observed in patients receiving both dietary counseling and home-delivered meals, but not in those receiving meals alone. |

| Troyer et al. 2010 (88) | Randomized controlled trial/Study participants were randomly assigned to 4 groups: 1) diagnosis-related diet/lifestyle literature, 2) therapeutic meals, 3) medical nutrition therapy (MNT), and 4) MNT-plus-therapeutic meals/Face-to-face in-home interviews and dietary recall collected at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months | 298 individuals diagnosed with hyperlipidemia or hypertension / ages 60+ in metropolitan county of North Carolina, the study sample included only those who were not intermediate DASH accordant at baseline (n = 210) | DASH accordance | Participants who received meals were 20% more likely to reach intermediate DASH accordance by 6 months and 18% more likely to meet saturated fat accordance at 12 months. |

| Troyer et al. 2010 (89) | Randomized controlled trial/Study participants were randomly assigned to 4 groups: 1) diagnosis-related diet/lifestyle literature, 2) therapeutic meals, 3) medical nutrition therapy (MNT), and 4) MNT-plus-therapeutic meals/Face-to-face in-home interviews and dietary recall collected at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months | Analytical sample of 298 adults >60 with hyperlipidemia and/or hypertension in large metropolitan county of North Carolina | Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) | Combination of MNT (medical nutrition therapy) and therapeutic meals did not have an independent significant effect on QALYs. A 95% probability that therapeutic meal delivery is cost effective and 90% probability that MNT is cost effective was reported. |

| Silver et al. 2008 (90) | Randomized crossover counterbalance design where participants received regular and enhanced (higher calorie) version of preweighted HDM on alternate weeks/Face-toface in-home interviews and 24-hour dietary recalls conducted by phone | 45 older adults from the Kramer Senior Services Agency in West Palm Beach, FL (31 F, 14 M) | Meal and 24-hr nutrient intakes | Enhanced meal day resulted in significant increase in mean lunch energy intake, but no significant difference in energy intake for breakfast and dinner. |

| Haynes et al. 1999 (91) | Randomized Controlled Trial/Participants randomized to either a control group or a prepared meal plan group Campbell’s Center for Nutrition and Wellness (CCNW), which included prepackaged, nutrient dense meals and snacks for 10 weeks after baseline assessment/In-home interviews and assessments, telephone interviews and 3-day food records | 251 outpatients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes from 6 medical centers in the U.S and Canada | Blood pressure, carbohydrate metabolism, lipoproteins, homocysteine, weight, nutrient intake, and compliance with a complete prepared meal plan compared to a usual-care dietary therapy | Blood pressure, carbohydrate metabolism, and weight improved on both plans. The nutritionally complete CCNW plan offers greater improvement in lipids, blood sugar, homocysteine, and weight loss. |

| Quasi-experimental Design Using Receipt of Home-delivered Meals as the Intervention | ||||

| Lee et al. 2011 (92) | Quasi-experimental design comparing recipients versus waitlisted applicants of OAANP Three waves of self-administered mail surveys at 4-month intervals | Final sample of 4,731 individuals either receiving or waitlisted for OAANP services in Georgia in 2008 | Food insecurity measured using a modified version of the 6-item USDA Household Food Security Survey Module | At baseline, 54% of sample was food insecure. Higher food insecurity was reported in the waitlisted group (45.9%) compared to participants (29.3%). Odds of becoming food secure over 4 month period were 1.65 times greater for participants. |

| Roy and Payette 2006 (93) | Quasi-experimental design with pre-test and post-test of users and non-users of MOW | 20 users and 31 non-users of MOW (ages 65+) in frail, free-living elderly population in Sherbrooke, Quebec in Canada | Dietary intakes of frail elderly | At baseline, dietary intakes were below estimated average requirements in both groups. At post, intake of most nutrients increased in MOW group only. |

| Edwards et al. 1993 (94) | Randomly selected patients with diabetes who either were or were not receiving HDM were interviewed in their homes at one time point | 79 diabetic persons receiving HDM (program group) and 75 diabetic persons on HDM waiting list (comparison group) in NY State | Health status, dietary practices, hospitalization, various blood levels | The HDM group was less likely to report food insecurity and more likely to report a diverse diet. The Wait-list group exhibited more uncontrolled diabetes and hospitalization than the HDM group. |

| Evaluation of Impact of Home-delivered Meals Using Administrative Claims Data, State Program Reports, or Surveys of Providers of Service | ||||

| Thomas and Mor 2013 (95) | Ecological observational of aggregate-level data | Aging Integrated Database for the number of clients for home delivered meals and Title III-C2 expenditures from State Program Reports for the period 2005–09 matched with LTCFocUS.org data set (at Brown University) which combines variables from the Online Survey Certification and Reporting databases, the national Minimum Data Set (resident level data) | Medicaid spending | It is estimated that if all states increased by one percent the number of adults aged 65 and older who received home-delivered meals in 2009 under Title III of the OAA, total annual savings to states’ Medicaid programs could have exceeded $109 million. This savings is a reflection of expected older adults who could remain at home rather than enter a nursing home for long term care. |

| Buys et al. 2012 (96) | Ecological observational of aggregate-level data | Aging Integrated Database, including data from 2007, 2008 American Community Survey and State Program Reports; Minimum Data Set for rates of nursing home institutionalization; Home and Community Base Services and Long Term Care Expenditures from Thomson Reuters’ annual report, from AGID on AoA expenditures, and state spending from AARP annual report | Nursing home admission | No effect was observed for OAA Nutrition Services on changes in rates of nursing home residency. However, states that directed a greater proportion of their long-term care expenditures to home and community-based services appear to have more reductions in their rates of nursing home residency. |

| Xu et al. 2010 (97) | Administrative claims data | 1,354 Indiana Medicaid recipients enrolled in the Aged and Disabled waiver program ages 65+ | Time to hospital admission, Volume of home-and community-based services | More attendant care, homemaking services, and HDM was associated with a lower risk of hospitalization |

Nearly half of the studies (n=39) represent a cross-sectional single point in time (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56). Thirty-two of these cross-sectional studies report on a single sample (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46), and with the exception of one national sample (32), the samples were drawn from areas smaller than or equivalent to individual US states. Study designs varied and included face-to-face interviews, telephone surveys, mail surveys, and chart reviews. Most studies collected markers of nutritional status including: 1) self-reported food diaries or dietary recalls, 2) anthropometric measurements of weight and height to derive body mass index, 3) blood draws, and 4) assessment of nutritional risk (typically the DETERMINE nutrition risk checklist used routinely by the OAA programs and in more recent studies the Mini Nutrition Assessment). All of these studies were descriptive, reporting on percent of participants with certain characteristics, such as basic demographic characteristics of those being served and their nutritional risk, food security, and satisfaction with meals program. Not surprisingly, these studies find that program participants are at high nutritional risk, experience food insecurity, and are satisfied with the meals program. One early study by Vailas et al. included measures of quality of life of participants (34). Some studies made efforts to evaluate differences between groups within their sample. For example, Sharkey compared Mexican Americans and non-Mexican Americans who were both receiving home-delivered meals; he found that Mexican Americans experienced greater nutritional risk (26).

Four cross-sectional descriptive studies compared older adults who were receiving home-delivered meals with those who were not; in these studies receipt of meals was the primary comparator (47, 48,49, 50). These studies varied tremendously in sources of data and sample sizes ranging from administrative data (n=31,341) to groups of patients (n=294) to a convenience sample (n=54). Two studies conducted within the last two years are notable. Lee and her colleagues compared older Georgians receiving Older Americans Act Nutrition Program Services with those receiving other Home and Community-Based services (n=31,341) (47). This is the first report of this recently obtained data; preliminary findings indicate that those who receive home-delivered meals represent a more vulnerable group with respect to sociodemographic, economic, and functional characteristics. Another paper by Luscombe-Marsh et al. reporting on a sample from South Australia found that those who were poorly nourished and receiving MOW compared with those who were poorly nourished and not receiving MOW were less likely to be admitted to a hospital within a 12 month period (48).

Six additional cross-sectional descriptive studies were identified (51, 52,53, 54, 55, 56). DiMaria-Ghalili compared client satisfaction surveys from MANNA meal recipients in Philadelphia to OAA recipients from the Northeast and nationally; she and her colleagues found that the MANNA recipients were more satisfied, but less food secure (51). The additional five studies were similar in that they started with a sample (client records, patient records, or respondents in the National Long-Term Care Survey) and were interested in identifying characteristics associated with utilization of community-based services, including home-delivered meals. Home-delivered meals were often used, but factors associated with use of those services were not consistent across studies. For example, one study found that living alone was associated with receipt of home-delivered meals (54), while another study found that living alone was associated with non-receipt of home-delivered meals (56).

Nine studies involved a pre- post-assessment of home-delivered meals on some outcome (57, 58,59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65). These studies attempted to determine: 1) whether receipt of home-delivered meals improved participants’ status along some dimension (e.g., nutritional status, nutrition risk) (57, 58,59, 60, 61, 62); 2) whether changes were observed in participants’ use of formal or informal care (64); or 3) what accounted for withdrawal or continuance in home-delivered meals programs (63, 65). More recent studies included outcome measures of anxiety, well-being, and loneliness in addition to the standard nutritional status outcomes (57, 58). All studies examining changes in participants’ status identified improvements.

Seven longitudinal observational studies were identified that examined some pattern, predictor, or outcome related to home-delivered meal service utilization (66, 67,68, 69, 70, 71, 72). Several of these studies relied upon large surveys (i.e., National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Georgia Advanced Performance Outcomes Measurement Project 6, the Second Longitudinal Study of Aging, the Health and Retirement Study, and the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old). Outcomes varied and included: nutrient intake and risk, hospital readmission, and use of home and community-based services, including home-delivered meals. Generally, these studies found that use of home-delivered meals was associated with poorer status along multiple domains and increased likelihood of being hospitalized or institutionalized.

Thirteen studies included in this review reported on a non-randomized intervention involving home-delivered meals (73, 74,75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85). Most of these involved tweaking or adding something different to existing home-delivered meals programs; these included: adding snacks (73), allowing food choices (74), receiving nutrition education (75), receiving meals post-hospital discharge (76, 78), adding breakfast (79), providing “heart healthy” meals and education (81), adding more meals and snacks (80), taking homebound older adults out to eat (82), adding dietary supplements (84), and providing frozen meals (85). Some studies were single group designs, while others had a comparison group. Nutritional and functional status were the primary outcomes for all studies except for one measuring hospital readmission and quality of life (76); one measuring increased access to service (83); and one measuring client approval, effect on client’s social contacts, and cost efficiency (85). In all of these studies, improvements were observed.

Six papers were identified that reported on findings from a randomized controlled design (86, 87,88, 89, 90, 91). All of these studies, except one (90), focused on participants with hypertension or hyperlipidemia and the home-delivered meal intervention was based on a DASH or similar therapeutic meal. Studies aimed at improving cardiometabolic outcomes reported mixed findings with some studies reporting improved outcomes and others reporting none. It is difficult to make comparisons because the interventions themselves contained different components (e.g., nutrition education and medical nutrition therapy) and different outcomes (e.g., body composition, laboratory values, DASH accordance, quality of life, nutritional intake). In the one study that evaluated whether increasing nutrient density of foods in older adult recipients of home-delivered meals, the investigators did find an increased energy intake in the intervention group (90). This study relied upon self-reported intake.

Three studies relied upon a quasi-experimental design using receipt of home-delivered meals as the intervention (92, 93, 94). All studies compared clients receiving home-delivered meals with those who were on a waiting list. Lee et al. (92) and Roy and Payette (93) employed a pre- post-design comparing changes observed from baseline to follow-up. In all three studies, the groups receiving home-delivered meals had better outcomes as measured mostly in terms of food security and dietary intake. The study by Edwards et al. restricted their randomly selected sample to persons with diabetes (94). These researchers found that persons not receiving meals were more likely to exhibit uncontrolled diabetes and hospitalizations.

Three studies evaluated the impact of home-delivered meals using administrative claims data and state program reports on outcomes related to service utilization and healthcare spending (95, 96, 97). Thomas and Mor (95) and Buys et al. (96) both took an ecological approach and analyzed data aggregated at the state level to examine outcomes for Medicaid spending and nursing home admission, respectively. While Thomas and Mor estimate that cost savings could be realized if states expanded their home-delivered meal programs (presumably because older adults could remain in the community instead of entering a nursing home [which is more costly]), Buys et al. found no association between expenditures on home-delivered meals and nursing home admissions. Both groups of authors pointed to the need to evaluate individual-level data. Toward that end, Xu et al. used administrative claims data from Medicaid Aged and Disabled waiver participants from Indiana and found that use of home-delivered meals was associated with lower risk of hospitalization (97).

DISCUSSION

A recent editorial appearing in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition observed: “[T]he sparseness of outcomes research on the OAA Nutrition program is one of the reasons why federal funding has grown only 6-fold since its inception in the 1970s, whereas the plethora of research on the Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) has helped WIC grow its federal funding 332-fold in the same time period” (98). The title of that article was “More research on nutrition and independence, please.” We would add to that title: “More rigorous research on nutrition and independence, please.”

Our comprehensive review contains 80 articles. In contrast, Zhu and An in their more restrictive review identified only eight studies that met their more stringent criteria for inclusion necessary to identify the impact of home-delivered meals programs (8). Zhu and An additionally conducted a quality assessment of the studies included in their review along the following dimensions: 1) a control group was included, 2) baseline characteristics between control and intervention groups were similar, 3) the intervention period lasted for at least four weeks, 4) the measures were reliable and valid,) participants were randomly recruited from a well-defined population, 6) attrition was analyzed and determined not to differ between control and intervention groups, 7) potential confounders were controlled in the analyses, and 8) study procedures were documented. The eight studies included received a total mean study quality score of 5 (with a possible range of 1 [worst] to 8 [best]). We did not conduct such a quality assessment in our review, but are confident that the average score would not be higher for articles included in our review.

Most studies included in our review were, in fact, descriptive and did not report on outcomes. The most commonly reported outcomes were nutritional status based upon self-reported dietary intakes. While Zhu and An consider that a reliable and valid measure, we are increasingly skeptical of its use given the preponderance of evidence that it ought not be used in scientific investigations (12). There are other measures that can be evaluated, including death, disease, disability, discomfort, dissatisfaction, and destitution or dollars expended for health services. To our knowledge, no study has investigated either death or destitution. Studies by Sharkey are notable for their focus on disease and disability/functional status (27, 31, 61). An increased focus on quality of life, satisfaction, and health service utilization are also important and increasingly being used by investigators to evaluate program impact (e.g., 57, 58).

While quite a few papers investigated some aspect of poverty status and/or food security, none dealt explicitly with costs from the participants’ perspective. Two papers dealt with costs from the perspective of payers of services. Thomas and Mor (95) and Buys et al. (96) considered costs to Medicaid and states. While Thomas and Mor found that increased spending on home-delivered meals could be cost-saving to Medicaid through reduced likelihood of at-risk older adults entering nursing home, Buys et al. research did not support this finding. Both studies relied upon data aggregated at the state level, rather than individual-level data. These studies are on the vanguard of where some future research ought to be directed—though, using individual-level data.

Most studies included in this review are cross-sectional, have a small sample size, and are limited to a particular setting or participant population. Only six studies involved a randomized controlled design, and, in five, the focus was not on home-delivered meals, per se; but on anti-hypertensive meals that happened to be home-delivered for a hypertensive sample (86, 87,88, 89, 90, 91). Three studies did employ a quasi-experimental design that used a waiting list control group to compare with the group receiving home-delivered meals (92, 93, 94). Several studies used administrative claims data in various ways. Moving forward, it is necessary to conduct complementary studies including randomized controlled trials that can evaluate program efficacy and large observational studies (employing state-of-the-art analytical methods) that can evaluate program effectiveness. In this issue, Thomas clearly identifies the issues related to improvements needed with respect to data quality and management at the national level (16). The same is true, as well, at the state and local levels. The report by Lee et al. and Satterfield et al. from Georgia are exemplars of approaches other researchers in partnership with their state agencies might take (47, 68).

Of note, with the exception of the Millen et al. (32) and Corson et al. (83) articles which appeared in peer-reviewed journals, we did not include any reports that were commissioned by either the Administration on Aging or, more recently, the Administration for Community Living to conduct a program evaluation of the OAA Nutrition Services. Since the start of the nutrition program, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. has conducted two such evaluations and is currently conducting a third related to costs (99, 100,101, 102, 103, 104). These reports are largely descriptive, reporting on characteristics of program participants, and do not report on outcomes. It is time to move beyond reporting descriptive statistics of program participants.

We are encouraged by recent initiatives at the national level that may be opportunities to conduct more rigorous research evaluating outcomes. These include:

Meals On Wheels Association of America (MOWAA) was awarded a cooperative agreement from the Administration on Aging through a competitive process for the award period (2011–2014) and subsequent award period (2014–2017) to host the National Resource Center on Nutrition and Aging. In their second renewal period, increased efforts have been devoted to supporting research evaluating outcomes. Indeed, one study included in this special issue was supported by one of a set of grants given to select MOWAA member agencies to help “Expand the Vision” of MOWAA, which is to end senior hunger by 2020. Additionally, in partnership with AARP Foundation (a strong partner who has a commitment to ending senior hunger [See: http://endseniorhunger.aarp.org/]), who provided $350,000.00 for funding, MOWAA awarded Kali Thomas a grant to conduct a randomized controlled trial evaluating different delivery models for home-delivered meals.

“On August 1, the NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) will establish the Office of Nutrition Research within the NIDDK Office of the Director. The new office will assist in leading a trans-NIH group that will strategically plan new initiatives for NIH nutrition research” (http://www.niddk.nih.gov/news/research-updates/pages/niddk-establishes-office-nutrition-research.aspx). While not a focus of this review, it was observed that few studies relied upon extramural funding that would have undergone peer-reviewed scrutiny. Opportunities exist to support high impact and high quality research, especially related to home-delivered meals for older adults with cardiometabolic disease who are transitioning from hospitals to home.

The Institute of Medicine will be hosting a Workshop on “Meeting the Dietary Needs of Lower Income Older Adults” in Washington, DC in the Fall of 2015. This workshop will bring together thought leaders who will present and discuss ongoing research and research needs. The outcomes of this Workshop may be a starting point to establish research priorities.

Home-delivered meals are a popular program that may help older adults maintain their independence within their own homes and communities. Greater and improved evidence is needed to: 1) gain insight into why so few eligible older adults access home-delivered meals programs, 2) support expansion of home-delivered meals to all eligible older adults, 3) better identify what home-delivered meals models alone and in combination with other services works best and for whom, and 4) better target home-delivered meals programs where and when resources are scarce.

Take Away Points.

Studies focused on home-delivered meals to older adults are mostly descriptive and do not report on outcomes.

The most frequently reported outcomes in studies focused on home-delivered meals for older adults are measures of nutritional status based upon self-reported dietary intake.

Studies focused on home-delivered meals to older adults are mostly cross-sectional, have a small sample size, and/or are limited to a particular setting or participant population.

More rigorous research, including complementary randomized controlled trials and large observational studies, is needed to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of home-delivered meals for older adults on multiple outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K07AG043588).

Contributor Information

Anthony D. Campbell, Department of Sociology, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Alice Godfryd, Department of Health Care Organization and Policy, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

David R. Buys, Department of Food Science, Nutrition, and Health Promotion, Mississippi State University, (MSU), Starkville, Mississippi USA; MSU Extension Service; Starkville, Mississippi, USA; Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station, MSU, Starkville, Mississippi, USA.

Julie L. Locher, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Comprehensive Center for Healthy Aging, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Nutrition Obesity Research Center, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Department of Health Care Organization and Policy, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

References

- 1.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Nutrition and Healthy Aging in the Community: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locher JL, Wellman NS. “Never the twain shall meet:” Dual systems exacerbate malnutrition in older adults recently discharged from hospitals. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2011 Jan;30(1):24–28. doi: 10.1080/01639366.2011.545039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tina Marie. Platter Angels. [posted December 5, 2013, accessed April 2, 2014]; http://www.cctvcambridge.org/Meals%20on%20Wheels. [Google Scholar]