Abstract

Ties to parents or grown children may be the most important social relationships in an adult’s life. Research examining intergenerational relationships has focused on three broader topics: (a) the strength of emotional bonds, (b) exchanges of social support, and (c) the effects of the relationship on individual well-being. This review considers some of the major theoretical developments in the field including solidarity and intergenerational ambivalence theory as well as the newly developed multidimensional model of support. We also consider weaknesses in the research and theories to date and provide suggestions for future research.

Keywords: Intergenerational relationships, Intergenerational ambivalence, Intergenerational exchanges, Family solidarity, Late life family

During the past 30 years, romantic ties have become more tenuous due to elevated divorce rates and increasing numbers of adults who delay marriage or remain single. By contrast, over the past 30 years relationships between adults and their parents have strengthened. Behavioral indicators of the parent-child tie (e.g. coresidence, frequency of contact, exchanges of support) show increases, particularly among young adults and their parents [1]. Intergenerational ties may become even more salient in late life, when romantic partners may be deceased, and the desire for meaningful social interactions and social support intensify. A tie to a grown child may be an older adult’s most important relationship.

This review describes current research regarding relationships between adults and their parents. We present research and theory addressing emotional and supportive aspects of these ties and describe how relationships between older adults and their children may contribute to each party’s well-being.

Emotional Qualities of Intergenerational Ties

Emotional aspects of intergenerational ties are important for two reasons: (a) emotions and affection may partially explain motivation for contact and support, and (b) emotions appear to be a key pathway through which intergenerational ties influence physical and psychological well-being. Several theories address positive and negative features of parent-child bonds, but a comprehensive theoretical understanding of ties between adults and parents is absent. Two theoretical models have been applied widely to study emotional qualities of parent-child ties.

Solidarity Theory

Solidarity theory initially set the tone for research regarding bonds between adults and parents, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. Drawing from classic sociological and psychological theories on group processes, solidarity theory emphasizes positive qualities of the tie associated with structural features. Indeed, initial statements regarding the tie considered how contact, emotional bonds, and support exchanges are reciprocally related, and more recent statements elaborate further on these links [2]. Thus, there is not a strictly causal relationship of one factor to another. Subsequent elaboration of solidarity theory also highlighted the influence of value similarity and structural constraints such as proximity [3]. That is, parents and children who share structural similarities (e.g. gender, proximity) benefit from shared values and strong emotional bonds. Further, beginning in the 1990s, the conflict perspective recognized negative as well as positive qualities of this tie and suggests that background characteristics and structural factors (e.g. coresidence) also contribute to interpersonal tensions in this tie [4, 5].

Solidarity models have often focused on how positive qualities of this tie vary by generation and age. Studies consistently find that parents view the parent-child tie in a more positive light than do their children. Scholars argue that this bias reflects an ‘intergenerational stake’ the parents have in their children [6]. Older parents and children also typically report more positive and less negative relationships than younger ones report [7, 8]. One study of three generations found both age and generational differences. Older parents viewed ties with their offspring more favorably than middle-aged offspring viewed ties to their parents, but there was no generational difference between middle-aged parents and their young adult offspring [7]. The findings indicated that the intergenerational stake may increase as parents and children grow older.

Finally, throughout the 20th century, scholars noted gender differences in relationships between adults and their parents, with dyads involving women (i.e. mothers and daughters) reporting stronger positive and negative emotional qualities in their ties [8, 9]. These gender differences remain in the 21st century. That is, mothers give more support to their grown children and report stronger bonds than do fathers [10, 11]. As we discuss later, this is particularly the case when the parents are divorced or never married – bonds to the father may be almost non-existent. Sons and daughters do not look as distinct in their intergenerational bonds in recent years, however. Rather, the filial role has begun to shift in ways that are less gender-differentiated.

Ambivalence Model

During the past decade, the intergenerational ambivalence model [12] has come to the fore of research on emotional aspects of relationships between adults and their parents. The model is entrenched in two distinct disciplinary roots: psychology and sociology. Intergenerational ambivalence also has been operationally defined in two ways, as: (a) simultaneous and conflicting emotions (positive and negative feelings), or (b) a subjective sense of feeling conflicted or torn. Each approach has particular limitations.

Sociological ambivalence has limited capacity for empirical testing. Premises of sociological ambivalence suggest conflicting norms for the parent-child relationship give rise to ambivalence. This premise is theoretically appealing, but difficult to validate empirically. Research would have to establish the clarity of norms – a vague and imprecise undertaking. Because norms exist at a cultural rather than individual level, a test of unclear norms would necessitate examining the clarity of different group norms and comparing ambivalence levels of those groups.

Instead, ambivalence researchers have measured statuses characterized by conflicted norms, such as being female or a caregiver. Yet, these statuses also are associated with other factors. For example, women tend to experience stronger emotions than men do; thus, women are likely to experience both positive and negative feelings (i.e. ambivalence) in their relationships. Moreover, the contrasting group, men, do not have clear norms for parental ties. Similarly, alternate explanations are evident for caregivers’ ambivalence; caregivers typically love a care recipient who is in decline, generating mixed feelings.

As mentioned previously, assessments of ambivalence also reflect two prominent measurement approaches. Several studies have combined independent ratings of positive and negative feelings to create an index of ambivalence; more intense feelings generate higher ambivalence scores [13, 14]. Research has identified correlates of these scores including appraisals of the other party and structural characteristics of the tie. For example, parents are more likely to experience mixed feelings regarding offspring who suffer problems or who are less successful in marriage or career [15, 16].

Nonetheless, this approach has limitations. A review of the literature suggests negative feelings may account for what researchers label as ‘ambivalence’. Many parents and grown children experience affection for one another, and ceiling effects arise in positive qualities of the tie. Thus, variability in negative feelings explains much of the observed variability in ambivalence [4].

Finally, sociologists have examined individuals’ subjective appraisals of feeling torn or conflicted regarding the relationship, also called ‘direct measures’ of ambivalence [17, 18]. Studies relying on subjective assessments of ambivalence find that parents report low levels of ambivalence toward their children [18], though nearly half of participants report at least some of these subjective feelings of being torn [17]. A principal limitation of examining ambivalence as a perception of being torn or conflicted involves individuals’ ability to recognize and articulate their feelings. Thus, some of the observed differences in reports of ambivalence may reflect variability in awareness rather than variability in relationship qualities.

In summary, the intergenerational ambivalence model has accrued important findings regarding qualities of intergenerational ties. Yet, ambivalence, per se, may not accurately portray the complexities of parent-child tie. Rather, negativity may account for the variability in parents’ and children’s relationships. Additional research is necessary to better understand emotional qualities of these ties.

Future Directions in Research on Emotional Qualities of Parent-Child Ties

Changes in the structural features of families in recent decades encourage reevaluation of the solidarity frame work. Adults in the US and Western Europe are less likely to be married than in the past, and single parents (particularly mothers) may have stronger ties with children than do married parents [19]. Indeed, in some families, parents and children alike may go through several iterations of partnering and unpartnering across adulthood. A model that addresses vicissitudes in intergenerational bonds accompanying such changes is necessary to shed light on parent-child relationships in the 21st century.

At the same time, potential for contact between generations has improved dramatically with the advent of communication technologies such as inexpensive long-distance rates, cell phones, and web cameras. Research should examine the use of these technologies in intergenerational ties. Geographic proximity is no longer necessary for parents and children to have emotionally supportive or close relationships, but other types of support may still require face-to-face contact.

To extend research on emotional qualities of relationships, reconceptualization of the ambivalence model also is warranted. At the very least, the two types of assessments appear to measure distinct constructs: (a) subjective feelings of being torn, and (b) simultaneous positive and negative emotions [18]. The field needs to better differentiate these forms of ambivalence.

Further, for both forms of measurement, scholars need to consider what low ambivalence means. With regard to mixed emotions, Uchino et al. [14] have suggested that when individuals do not experience ambivalence in a relationship, they may feel: (a) primarily positive about the tie, (b) primarily negative about the tie, or (c) disengaged from the tie. With regard to feeling torn or conflicted, researchers might address complementary perspectives such as confidence about behaviors in the tie, or feeling calm and at ease in the tie. Thus, ambivalence research might yield a more comprehensive view of intergenerational ties if such comparison categories were included.

Future research also might address age differences in the nature of ambivalence. Fingerman [20] compared young women and their mothers to older women and their mothers. The younger dyads described their relationship in distinct positive and negative terms; the good interactions were wholly positive and the bad interactions were wholly negative. By contrast, the older mothers and daughters provided more nuanced responses, intermingling negative remarks in their descriptions of positive events. Age differences in relationships and these types of complex emotional experiences warrant increased attention.

Finally, researchers should consider biases in the types of people who participate in research. Studies of intergenerational ties include samples that generalize to the population with regard to demographic characteristics such as social class and gender. But some parents and children are unlikely to participate in such studies, including: (a) parents and children who have primarily negative relationships, and (b) parents and children who have no relationship. Instead, data regarding these ties may be derived from large studies addressing other topics, such as mental health, though assessments of relationship quality will be less rich. As we discuss later, additional methodological approaches to assess this tie also may yield new and important findings.

Intergenerational Ties and Support Exchanges

Thirty years ago, Troll [21] argued that older adults serve as the ‘family watchdog’, offering support if needed when crises and problems arise. However, research has typically focused on upstream support (i.e. from children to aging parents) rather than downstream support (i.e. from older adults to adult children) as Troll proposed. For example, most research on intergenerational support has focused on caregiving for older adults suffering physical or mental declines [22].

Yet, considerable support exchanges occur between adults and their parents prior to the onset of parental health declines. In Western cultures, throughout much of adulthood, support typically flows from parents to grown children, rather than the reverse [10, 23]. These patterns may only be altered at the end of life, when parents require care.

When adults are in their 20s, 30s and 40s, they may exchange mundane support with parents. Support is evident when a grown child accompanies a recent widow to the theater, or a grandmother listens to a new mother share the minutiae of her baby’s development. Parents and grown children share personal concerns, advice, provide input on decisions, and engage in companionship in addition to providing financial and practical help. Indeed, simply listening to talk about one’s day is the most frequent support that adults and parents of all ages exchange [20, 24].

The family context of support also warrants consideration. Intergenerational support has been measured as involving one child and one parent [25]. In real life, however, three or four generations are alive, with members of the middle generations exchanging support with multiple members of generations above and below [10, 23]. Recent studies in the USA and Netherlands have also shown that support often involved multiple family members across multiple generations [26, 27].

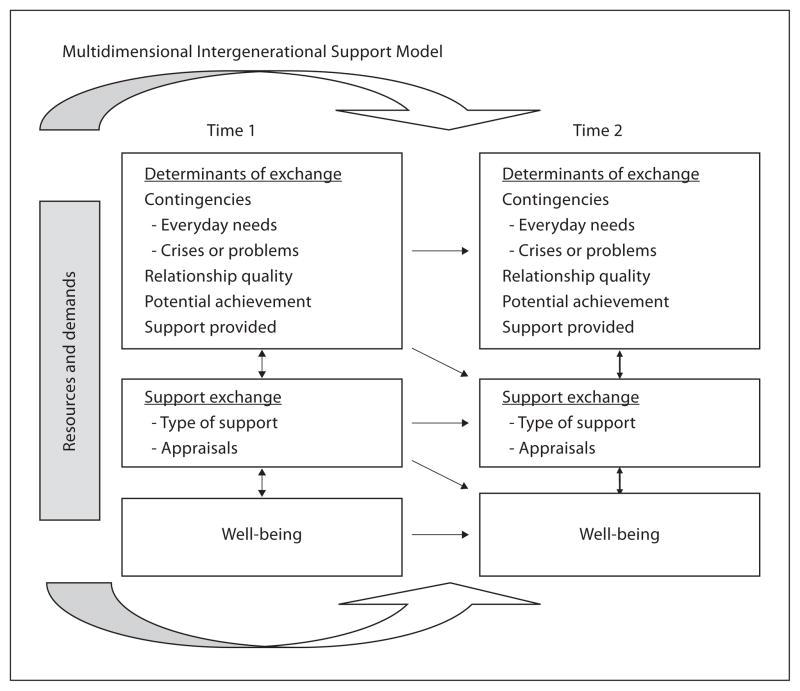

We have developed the Multidimensional Intergenerational Support Model (MISM) to provide an overview of intergenerational support in parent-child ties in adulthood. This model takes into account: (a) types of everyday support (e.g. financial, practical, emotional, advice, companionship, and technical help), (b) multiple family members (e.g. multiple grown children, middle-aged adults, aging parents), (c) varying needs, and (d) emotions involved in providing and responding to support. Further, this model allows for changes over time (fig. 1). In young adulthood, the bulk of support may flow from the parent to grown children, in midlife support exchanges may be more reciprocal, and in late life, the parent may become a net recipient of support from the grown child.

Fig. 1.

Multidimensional Intergenerational Support Model.

According to the MISM, support decisions reflect resources and demands. For example, members of different socioeconomic backgrounds provide different amounts and types of support [28]. Children in larger families receive less support from parents than grown children from smaller families. Interestingly, however, parents with a greater number of children provide more support overall [24]. Similarly, when middle-aged couples had a greater number of living parents, each parent received less support but the couple provided more support to parents in total [29]. Overall, findings examining multiple family members across multiple generations support a premise of resource depletion from the perspective of the recipient, but resource expansion [23] from the perspective of the provider. That is, individuals who provide support attempt to stretch their time and resources to give to as many family members as they can.

The MISM also addresses reasons why parents and grown children support one another. Theorists have conceptualized needs in terms of problems, particularly health problems that elicit support [25]. Parents and grown children do help one another when a crisis arises, but they also respond to a broader array of daily needs. For example, young parents often receive help with childcare from their own parents and students typically receive greater support than non-students [24, 30]. Moreover, after decades of investing time and effort in their children, parents may view their grown children as an extension of themselves [6] and continue to invest in their potential successes even after the children are grown [24]. In late life, however, when parents begin to incur crises and health declines, patterns of support may alter, with middle-aged adults increasing support to aging parents who are in need. Consistent with the premise of resource expansion, in these situations, the middle-aged adults continue to provide support to their grown children as well [10, 23].

Emotions also play a role in motivating intergenerational support, and in the implications of such support. Consistent with solidarity theory, support occurs most often in relationships characterized by affection and strong ties [10, 25]. Intergenerational support also involves complicated emotions, however. Parents experience stress from helping children who have problems [11, 31]. Yet, this stress does not deter parents from providing help. By the same token, there are situations where parents help grown children to achieve future goals and these situations may be rewarding. Similarly, grown children may either experience benefits of support from parents or feel the support was given in a manner that demands repayment [11].

Future Directions in Research on Intergenerational Suppport

In summary, the MISM extends prior models by generating a more complex and contextually based view of intergenerational ties. A downside of this model involves data limited to survey approaches (albeit from multiple family members). Future research might incorporate social psychological theories and research paradigms, including experimental designs, to identify motivations and behaviors underlying intergenerational support.

Future research might incorporate social psychological theories and research paradigms, including experimental designs, to identify motivations and behaviors underlying intergenerational support. For instance, family support occurs under a principle of resource expansion, with middle- aged adults stretching their time and efforts to provide to multiple family members in need [10]. Experimental paradigms might determine whether middle-aged adults hit a point where they are no longer able to do so.

Finally, the recent economic downturn has ramifications for family support. In many cases, economic loss extends beyond the immediate household in which it occurred. Middle-aged adults may step in to assist a grown child who has lost a job or an aging parent whose retirement savings were depleted or pensions cancelled. Similarly, grandparents may assist a college-aged grandchild with tuition. These multigenerational patterns warrant research attention.

Intergenerational Ties and Well-Being

The past decade has seen a surge in studies addressing adults’ relationships with parents or grown children and individual health and well-being both in the USA [32] and throughout Europe [3], suggesting scholars are interested in the topic globally. Indeed, given the frequency of contact between generations and the importance of the tie, it is no surprise that relationships between adults and their parents influence each party’s health and well-being. Two key mechanisms through which social ties influence well-being have already been discussed: (a) emotional responses and (b) social support.

Emotional Aspects of the Tie and Well-Being

Because many parents and grown children value their relationships, emotional aspects of this relationship appear to be associated with physical and psychological well-being for both parties. Moreover, given the long history of the relationship from early life, parents and grown children who do not value their relationships (or who are estranged) may suffer emotional and physical consequences.

Mixed emotions and ambivalence in this tie are associated with diminished well-being [3, 13]. Uchino et al. [14] have attributed the detriments of ambivalent relationships to inconsistent behaviors in this relationship, and the inability to predict whether a given encounter will be positive or negative. Moreover, unlike friendships, adults and their parents cannot replace one another, and, thus, may maintain contact characterized by negative feelings that are harmful to mental or physical health in the long run.

Research also shows that beyond the emotional aspects of the tie, children’s problems are particularly detrimental for parents’ well-being. Parents are sensitive to having a child who is suffering a problem, even when other children in the family are thriving or successful [1]. Other studies have found that parental well-being declines over time when grown children suffer distress, perhaps due to parental empathy [33]. It is also likely that parents experience disappointment and question their own abilities as parents when children suffer problems that seem avoidable (e.g. crime, drug addictions).

Similarly, when grown children have conflicted ties with their parents, they may suffer detriments. In extreme circumstances, early childhood experiences with parents may have lasting repercussions. For example, physical abuse by parents has lingering effects into adulthood [34]. More recent research suggests that continuity of the early relationship with parents is more the exception than the rule. The few longitudinal studies of children’s ties to their parents find continuities in relationships qualities are evident only from adolescence into young adulthood [35].

Support Exchanges and Well-Being

It is not clear whether support exchanges contribute to well-being for adults and their parents. Hundreds of studies document stress middle-aged offspring incur when caregiving for an aging parents [22], but there has been little attention to the impact of everyday support exchanges on parents’ and grown children’s well-being. Current models implicitly assume that support is helpful to the recipient and stressful for the provider. For example, a recent study revealed that receiving intense support from parents in young adulthood was beneficial for grown children [11]. For parents, however, providing intense support was associated with diminished well-being if the parents perceived their grown children as needing too much support. Such findings are consistent with parental reactions to offspring’s problems. Nonetheless, receiving support may be harmful if it undermines autonomy, and alternately, providing support can be beneficial. Future research should seek to disentangle when support is beneficial and when it is detrimental to both the parent and the child.

In summary, strong bonds between adults and their parents appear to be beneficial for both parties. Yet, mechanisms through which these associations occur are not well understood.

Future Directions to Integrate Research on Intergenerational Ties

New theoretical and methodological integrations could address key questions regarding the benefits of strong intergenerational ties. In the past decade, scholars have begun to study parents’ relationships with multiple children in the same family. The Within Family Differences Study [27] included a US sample of older mothers and all of their grown children, the Family Exchanges Study included a US sample of middle-aged adults, both of their parents, and all of their young adult children [10], and the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study incorporated multiple familial and nonfamilial social partners [26]. These studies have shown that parents differentiate among their children, favoring some children with greater affection or more support than other children [24, 27]. Current research is still constrained by the theories centering on individual dyads and pairs rather than small group processes, but new theoretical developments will continue to explain these variations and their implications.

A wider array of methodologies also might address gaps in this literature. Much extant research relies on self-reports of global qualities of the tie, which have no-table limitations. For example, individual differences in the sense of being loved have been difficult to identify among adults and parents, due to ceiling effects in ratings of affection. Observations made in real time might provide new insights into daily patterns in these ties. Due to modern technologies such as cell phones and e-mail, a majority of adults and parents have contact at least once a week. Daily diary or experience sampling assessments may yield data regarding emotions that arise in everyday interactions. For some grown children and parents, negative feelings may reflect communication and interaction styles, whereas for other parents and grown children ongoing relationship dilemmas set a tone for ambivalence.

Finally, the interplay between biology and psychosocial factors in the parent child tie warrant attention. For example, we know little about how genetics contribute to the emotional qualities of the tie. We also know little about the biological mechanisms that account for links between the parent child tie and health. Future research should consider biological indicators of stress (e.g. cortisol), for example, to uncover links between parent child relationship quality and well-being.

In summary, to move the field forward in understanding intergenerational ties, gerontologists should draw on theories and methodologies used to study other types of relationships and assess daily interactions in real time. The bond between adults and parents may involve biological underpinnings that evoke emotional reactions and daily positive and negative experiences that contribute to these sentiments. By investigating these aspects of intergenerational ties, we may gain a better sense of differences in these relationships.

References

- 1.Fingerman KL, Cheng YP, Tighe L, Birditt KS, Zarit S. Relationships between young adults and their parents. In: Booth A, Brown SL, Landale N, Manning W, McHale SM, editors. Early Adulthood in a Family Context. Berlin: Springer; 2012. pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengtson VL. Beyond the nuclear family: the increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. J Marriage Family. 2001;63:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowenstein A. Solidarity – conflict and ambivalence: testing two conceptual frameworks and their impact on quality of life for older family members. J Gerontol B Soc Sci. 2007;62:S100–S107. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Parent/child and intergenerational relationships across adulthood. In: Fine MA, Fincham FD, editors. Family Theories: A Content-Based Approach. New York: Routledge Academic; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fingerman KL, Birditt KS. Adult children and aging parents. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL, editors. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giarrusso R, Feng D, Bengtson VL. The intergenerational stake over 20 years. In: Silverstein M, editor. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Berlin: Springer; 2005. pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birditt KS, Zarit S, Fingerman KL. Intergenerational relationship quality across three generations. J Gerontol B Soc Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs050. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations across the Life Course. Amsterdam: Aldine de Gruyter; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fingerman KL. Aging Mothers and Their Adult Daughters: A Study in Mixed Emotions. Berlin: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fingerman KL, Pitzer LM, Chan W, Birditt KS, Franks MM, Zarit S. Who gets what and why: help middle-aged adults provide to parents and grown children. J Gerontol B Soc Sci. 2011;66B:87–98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingerman KL, Cheng YP, Wesselman ED, Zarit S, Furstenberg FF, Birditt KS. Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: intense parental support in adulthood. J Marriage Family. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00987.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luescher K, Pillemer K. Intergenerational ambivalence: a new approach to the study of parent-child relations in later-life. J Marriage Family. 1998;60:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fingerman KL, Pitzer LM, Lefkowitz ES, Birditt KS, Mroczek D. Ambivalent relationship qualities between adults and their parents: implications for both parties’ well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2008;63B:362–371. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.p362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TW, Bloor L. Heterogeneity in social networks: A comparison of different models linking relationships to psychological outcomes. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, Zarit S. Adult children’s problems and successes: Implications for intergenerational ambivalence. J Gerontol B Soc Sci. 2010;65:145–153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fingerman KL, Chen PC, Hay EL, Cichy KE, Lefkowitz ES. Ambivalent reactions in the parent and offspring relationship. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2006;61B:152–160. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.p152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Mock S, Sabir M, Sechrist J. Capturing the complexity of intergenerational relations: exploring ambivalence within later-life families. J Soc Issues. 2007;63:775–791. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suitor JJ, Gilligan M, Pillemer K. Conceptualizing and measuring ambivalence in later life. J Gerontol B Soc Sci. 2011;66:769–781. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fingerman KL, Pillemer KA, Silverstein M, Suitor JJ. The Baby Boomers’ intergenerational relationships. Gerontologist. 2012;52:199–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fingerman KL. ‘We had a nice little chat’: age and generational differences in mothers’ and daughters’ descriptions of enjoyable visits. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2000;55:95–106. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.p95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troll LE. Grandparents: the family watchdogs. In: Brubaker T, editor. Family Relationships in Later Life. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Son J, Erno A, Shea DG, Femia EE, Zarit SH, Stephens MA. The caregiver stress process and health outcomes. J Aging Health. 2007;19:871–887. doi: 10.1177/0898264307308568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundy E, Henretta JC. Between elderly parents and adult children: a new look at the intergenerational care provided by the ‘sandwich’ generation. Aging Soc. 2006;26:707– 722. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fingerman KL, Miller LM, Birditt KS, Zarit S. Giving to the good and the needy: Parental support of grown children. J Marriage Family. 2009;71:1220–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverstein M, Gans D, Yang FM. Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs. J Family Issues. 2006;27:1068–1084. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dykstra PA, Kalmijn M, Knijn TCM, Komter AE, Liefbroer AC, Mulder CH. Wave 1 (NKPS Working Paper No 4) The Hague: Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute; 2005. Codebook of the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study, a multi-actor, multi-method panel study on solidarity in family relationships. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Plikuhn M, Pardo S, Pillemer K. Within-family differences in parent-child relations across the life course. Curr Directions Psychol Sci. 2008;17:334–338. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swartz TT. Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Annu Rev Sociol. 2009;25:191–212. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Zarit S, Rovine MJ, Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Middle aged couples’ exchanges of support with aging parents: patterns and association with marital satisfaction. Gerontology. 2012;58:88–96. doi: 10.1159/000324512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attias-Donfut C, Wolff FC. The redistributive effects of generational transfers. In: Arbur S, Attias-Donfut C, editors. The Myth of Generational Conflict: The Family and State in Ageing Societies. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 22–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levitzki N. Parenting of adult children in an Israeli sample: parents are always parents. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23:226–235. doi: 10.1037/a0015218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umberson D, Pudrovska T, Reczek C. Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: a life course perspective. J Marriage Family. 2010;72:612–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knoester C. Implications of childhood externalizing problems for young adults. J Marriage Family. 2003;65:1073–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitzer LM, Fingerman KL. Psychosocial resources and associations between childhood physical abuse and adult well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2010;65B:425–433. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belsky J, Jaffee S, Hsieh KH, Silva PA. Child-rearing antecedents of intergenerational relations in young adulthood: a prospective study. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:801–808. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]