Abstract

Problem

Sexual violence is a public health problem in Haiti, potentially augmenting HIV transmission. Reports from L’Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haiti (HUEH) suggest severe underutilization of antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis (ARV-PEP) amongst rape survivors.

Method of Study

Cross-sectional design using mixed methods. Informational-interviews were conducted with HUEH personnel to learn about post-rape service offerings. HUEH surveillance data was used to estimate the sexual assault reporting rate/100,000; and to examine the proportion of survivors receiving ARV-PEP within 72 hours, stratified by age (<18 years, ≥18 years).

Results

Informational-interviews revealed that survivors were navigated through two hospital algorithms to receive post-rape care, however, less than 5% of victims sought mental health services. Surveillance data show that 2,193 sexual assault survivors (adult and pediatric) reported a rape to HUEH personnel between 2004 through first quarter 2010. Annual estimates suggest a 2-fold increase comparing cases in 2004 versus 2009. Between 2008–2009, uptake to ARV-PEP within 72-hours was lower for pediatric (38.4%; N=131/341) compared to adult survivors (60.1%; N=83/138) (χ2 = 18.8, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The prioritization of funding and comprehensive interventions that align sexual violence, HIV and mental health are crucial to support the timely uptake to ARV-PEP.

Introduction

Uptake to antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis (ARV-PEP) for HIV following sexual assault has been a challenge in many parts of the developing world. Barriers include, but are not limited to, delayed presentation after the abuse (beyond 72-hours)1, refusing an HIV test upon initial presentation1, limited availability of ARV-PEP2,3, challenges in pediatric dosing4, and low counseling referrals5 that might influence uptake and adherence to ARV-PEP6.

In Haiti, anecdotal reports from personnel at the largest publicly-funded hospital suggest there is severe underutilization of ARV-PEP amongst sexual assault survivors7. As background, since the 1990s sexual violence has become an increasing public health problem in Haiti due to political and economic instability8,9, which is now reaching epidemic proportions7,10,11. Data from the United Nations also shows that Haiti has the highest prevalence of HIV (1.9%) in the world outside of Sub-Saharan Africa12. Hence, within the Caribbean region Haiti has a dual epidemic similar to South Africa13.

To address these concerns, the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population (hereafter “MSPP” for the French acronym Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population) responded to the rape crisis by providing free ARV-PEP and pre/post HIV counseling at publicly-funded facilities throughout the nation. This policy is supported by Haiti’s National Plan for HIV/AIDS funded by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)14,15. Yet despite governmental initiatives uptake to ARV-PEP following sexual assault is reportedly low at l’Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haiti (HUEH), the largest publicly funded health facility in the nation. Unfortunately, little is known about the barriers that lead to low rates of health service seeking behavior post-rape, or the temporal link of service use with sexual victimization in this setting16,17. Hence, the primary author (L.G.M.) in collaboration with MSPP and HUEH conducted a mixed-methods pilot investigation to empirically examine the uptake to ARV-PEP in female victims of sexual violence seeking post-rape care at this facility. We believe that study findings may help raise awareness about the barriers to the efficient delivery of services in this resource-poor setting.

Ethics

HUEH is a tertiary care institution within MSPP, and ongoing operational surveillance is not considered research. The primary author (L.G.M.) received written authorization from MSPP and the Director General of HUEH to conduct information-gathering interviews with HUEH personnel. Approval was obtained to analyze HUEH surveillance data from the Institutional Review Board of Cambridge Health Alliance (former affiliation for L.G.M.).

Materials and Methods

Design

This investigation uses a cross-sectional design and mixed methods approach. Information-gathering interviews were conducted with HUEH personnel. HUEH surveillance data on the number of adult and pediatric survivors seeking post-rape care was used to estimate the hospital sexual assault reporting rate per 100,000 patient-encounters; and surveillance data was also used to measure the proportion uptake to ARV-PEP amongst survivors seeking care at HUEH.

Setting

HUEH Infrastructure

HUEH is the principal site for medical training and the largest health facility in the country. In 2006 an internal hospital report showed that HUEH had a total of 160,377 ambulatory patient-provider encounters18. This facility consists of primary services and 12 different sub-specialties including Maternity, Pediatrics, Laboratory Services, Community Health, Internal Medicine, Surgery and Neurosurgery, Urology, Dermatology, Ear Nose and Throat, Radiology and Epidemiology and Statistics, a Morgue and Medical-Legal Services.

HIV/STI/Pregnancy Testing at HUEH Post-Sexual Assault

At baseline and 3-months following a sexual assault, HIV testing was performed on sexual assault survivors seeking care at HUEH drawing whole blood specimens using a standardized algorithm of two rapid tests with discordant results settled by Western Blot [Determine™ HIV1/HIV2, (Abbott Pharmaceuticals)19]; Capillus™ HIV1/HIV2 [Cambridge Diagnostics Ireland Ltd]20. Syphilis tests were performed following sexual victimization using whole blood specimens for a rapid test [SD Bioline Syphilis 3.0™, (Standard Diagnostics)]. Pregnancy testing was performed on urine specimens using a rapid test [hCG Dipstrip™, (Cypress Diagnostics)]; and the forensic detection of spermatozoa was conducted if the victim presented to the hospital within 72 hours of the assault.

Study 1

Information-Gathering Interviews

Information-gathering interviews were conducted with HUEH personnel between 2008 and 2009. A total of 12 professionals (i.e., administrative, laboratory, medical, mental health and contractors) were interviewed which consisted of: 2 senior administrators, 1 data manager, 1 lab technician, 2 medical personnel (attending physician and senior nurse) and 2 psychologists, as well as rape crisis counselors that were contracted by MSPP to work at HUEH, including 2 psychologists, 1 physician and 1 manager. Questions were asked about common practices, policies and procedures for the delivery of post-rape service offerings.

Study 2

Surveillance and Sexual Assault Reporting Rate at HUEH

Surveillance data on the number of sexual assault survivors reporting a rape to HUEH personnel and seeking post-rape services at HUEH, between September 2004 to March 2010, was provided for analyses by the Department of Statistics and Preventive Medicine (author initials, P.N.). These data included adult and pediatric cases that were systematically collected from departmental logs (P.N.). An estimate of the annual HUEH sexual assault reporting rate was calculated using the 2006 HUEH patient-provider encounter load [N=160,377] as the denominator. The latter was used as a constant denominator for calculations including rape cases reported in 2004 through 2009 as no other patient-provider figures were available for the study period.

Measuring Uptake to ARV-PEP

Uptake to ARV-PEP, based on first dose given at HUEH, was examined for the period between September 2008 through August 2009 using data provided by the Department of Statistics and Preventive Medicine (P.N.). For this study, timely uptake to ARV-PEP is defined as within 72 hours following the sexual assault21–27.

To ensure that all adult and pediatric survivors who presented for care were considered in these analyses, and to account for the lag time between case presentation and documentation into departmental logs, the primary author (L.G.M.) obtained a separate spreadsheet from the attending gynecologist responsible to provide/supervise care and treatment of adult survivors (author initials, J.G.H.). Information on first dose of ARV-PEP to adults was recorded in clinical notes by the attending gynecologist (J.G.H.) and subsequently recorded into the departmental log. First dose of ARV-PEP to child rape survivors was actively collected by the attending gynecologist (J.G.H.) from clinicians in the Department of Pediatrics (where such information was routinely recorded into the pediatric log). Hence, a triangulation of data from the attending physician, pediatricians and data provided by the Department of Statistics and Preventive Medicine was compiled to determine the number of survivors seeking post-rape care at HUEH, and their uptake to ARV-PEP. No confidential patient information was provided for analyses except the age group of each survivor (<18 years or ≥18 years).

Results

Study 1

Informational-Interviews with Administrative, Laboratory and Medical Personnel at HUEH

Interviews with HUEH personnel revealed that most sexual assault survivors seeking post-rape care were commonly navigated through two algorithms, one specifically designed for sexual assault survivors, and the other designed for patients seeking the HIV Pre/Post Counseling and Testing (VCT) program18. However, it is unknown what proportion of survivors followed the medical algorithm versus the VCT algorithm, and a description of both is described below.

Medical Algorithm for Victims of Sexual Assault at HUEH

Interviews with medical and laboratory personnel revealed that all HUEH health care professionals received trainings on the national standards for the provision of post-rape care, which encompassed patient reception, clinical evaluation, laboratory testing and treatment.

Hence, when a rape victim sought care through one of three hospital entry points (i.e., emergency room, outpatient clinic or maternity clinic), HUEH personnel was trained to maintain the information as confidential, then orient the survivor towards patient care managers who would perform the first post-rape examination. The medical algorithm included a protocol for the retrieval of blood, urine and vaginal samples, and for the evaluation of HIV/STI status, pregnancy, detection of spermatozoa, evidence of rape and treatment of injuries. The protocol also included guidance for curative treatments, which included the care for severe lesions (dressings, sutures); the administration of analgesics, antibiotics and anti-anxiety drugs as needed; and post-exposure prophylactic treatments including a 4-week course of antiretrovirals, antibiotics for STIs, emergency contraception, and prophylaxis for the prevention of tetanus.

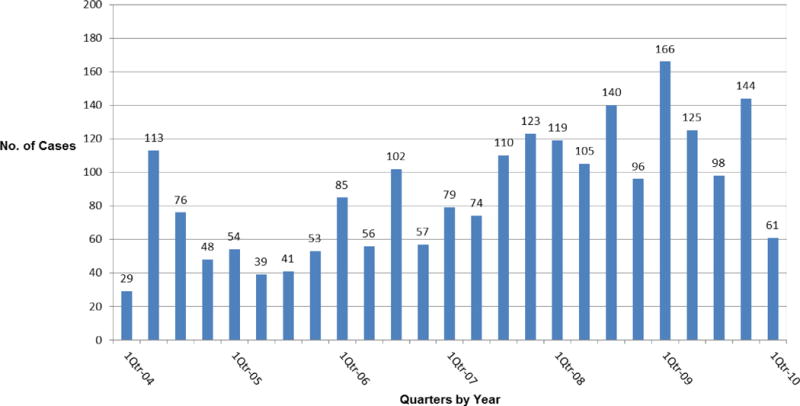

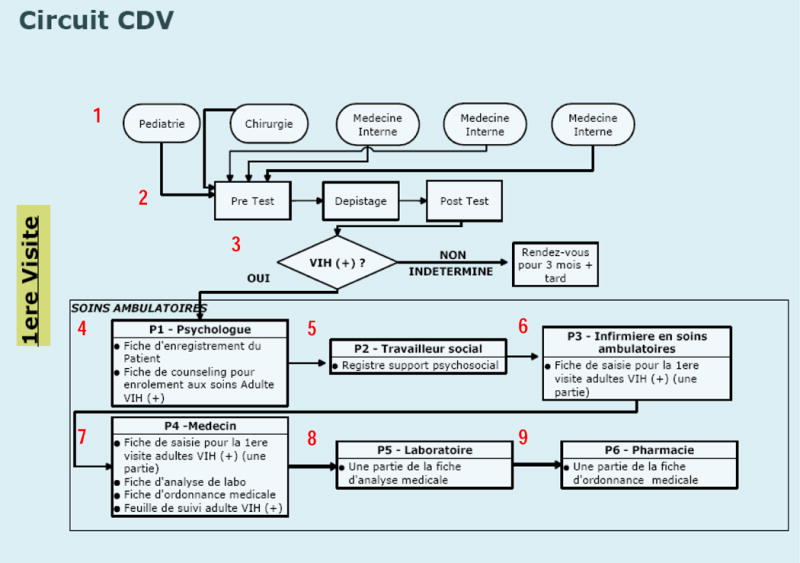

Algorithm for Volunteer HIV Pre/Post Counseling and Testing at HUEH

Interviews with administrative personnel produced a copy of the algorithm specifically designed for VCT clients [Figure 1]. The algorithm depicts 9 steps through which any hospital patient seeking an HIV test was directed through a hospital department for initial evaluation–Step 1 (Pediatrics, Internal Medicine or Surgery); Step 2 (HIV Pre/Post Counseling and Testing); Step 3 (Follow-up Appointment for 3-months if sero-negative or inconclusive). If sero-positive adult patients were referred to Step 4 (Psychology, for registration to receive HIV counseling services, adults only); Step 5 (Social Work, for registration to receive psychosocial support, adults only); Step 6 (Nursing in Ambulatory Care, to receive orders for the initial medical encounter as an HIV+ adult); Step 7 (Medicine, initial physician encounter to receive orders for medical plan, laboratory tests and follow-up appointment); Step 8 (Laboratory, to perform tests); and Step 9 (Pharmacy, for treatment according to medical plan).

Figure 1.

Cases of Sexual Assault at L’Hôpital Universitaire de l’État d’Haïti (2004–2010)

Informational-Interviews with Mental Health Personnel at HUEH

At HUEH mental health professionals consisted of in-house bachelor-level staff who were primarily VCT counselors, and graduate-level trained rape crisis counselors contracted by MSPP. In-house mental health staff had minimal expertise in post-rape psychopathology, therefore, all sexual assault survivors were referred to rape crisis counselors/contractors.

Interviews with both types of mental health staff revealed that the contracted counselors worked at several hospitals within the catchment area, and were only present at HUEH a few days per week. Thus, HUEH rape victims seeking mental health services were most often given a phone number to schedule an appointment with a rape crisis counselor; and this session would take place in a location requested by the victim. Upon further discussion the contracted counselors shared that less than 5% of HUEH survivors sought post-rape counseling; and that amongst survivors who scheduled an appointment many defaulted28.

Mental health personnel (in-house and contractors) also imparted that factors known to predict mental health service seeking29, and predict uptake and adherence to ARV-PEP30–34, were not systematically collected at HUEH during intake. These factors include, but are not limited to, background characteristics of the victim (e.g., education, socioeconomic status, marital status, history of sexual violence, history of childhood sexual abuse), characteristics of the assault (e.g., perpetrator type – partner, relative, acquaintance or stranger), severity of violence, drug/alcohol exposure during the assault, and prior traumatic events experienced by the victim.

Study 2

Surveillance and Sexual Assault Reporting Rate at HUEH

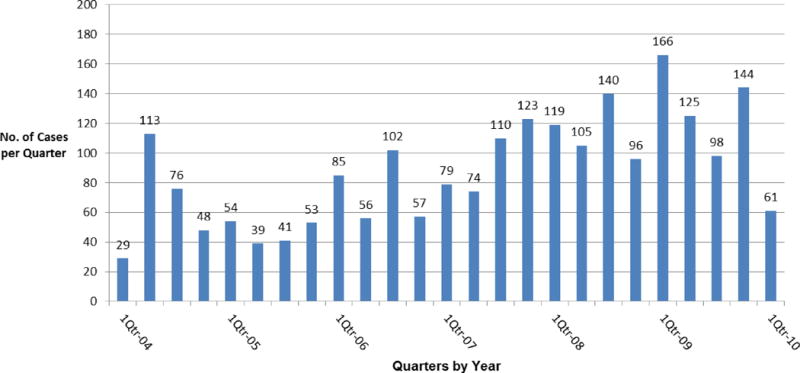

Surveillance data shows that approximately 2,193 sexual assault survivors (adult and pediatric) reported a rape to HUEH personnel, and sought post-rape services at HUEH between 1st quarter 2004 through 1st quarter 2010 [Figure 2]. Post-rape services consisted of medical, mental health and ARV-PEP, however only detailed information on uptake to ARV-PEP is available for 2008 through 2009, and described in the next section of this text.

Figure 2.

Cases of Sexual Violence Reported at L’Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haïti by Quarters (2004–2010)

The annual sexual assault reporting rate for 2004 is 165.9/100,000 persons which was calculated using the number of cases reported in 2004 (N=266) divided by the 2006 HUEH patient-provider encounter load (N=160,377) multiplied by 100,000. The sexual assault reporting rate for subsequent years (2005–2009) using the same denominator as a constant is 116.6/100,000 in 2005 (N=187); 187.1/100,000 in 2006 (N=300); 240.7/100,000 in 2007 (N=386); 286.8/100,000 in 2008 (N=460); and 332.3/100,000 in 2009 (N=533), respectively [Table 1]. Comparing rates in 2004 and 2009, these estimates suggest a 2-fold increase in survivors reporting sexual assault at HUEH between these two time periods.

Table 1.

Annual HUEH Sexual Assault Reporting Rate/100,000 Patient-Provider Encounters (2004–2009)

| Year | Number of Sexual Assaults Reported | Rate per 100,000* |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 266 | 165.9 |

| 2005 | 187 | 116.6 |

| 2006 | 300 | 187.1 |

| 2007 | 386 | 240.7 |

| 2008 | 460 | 286.8 |

| 2009 | 533 | 332.3 |

Uptake to ARV-PEP between 2008–2009

A total of 479 consecutive victims of sexual violence reported a rape at HUEH and sought care between September 2008 through August 2009, which consists of adult (N=138) and pediatric (N=341) cases. Across this 12-month study period, uptake to the first dose of ARV-PEP within 72 hours post-rape was 44.7% (N=214/479) for the combined study population. However, stratified results across age group show that only 38.4% (N=131/341) of pediatric survivors (<18 years) had uptake within 72 hours compared to 60.1% (N=83/138) of adult survivors (≥18 years); and this difference is statistically significant (χ2 = 18.8, p < 0.001).

Lessons Learned from Study 1and Study 2

Upon reviewing the findings of Study 1 with HUEH personnel and contractors, both groups shared lessons learned about the strengths/weakness of each algorithm, and also shared their perceptions about a survivors’ ability to navigate the HUEH health care system. With this information study authors were able to construct three hypothetical case scenarios which might help to explain the results of Study 2, specifically the low uptake to ARV-PEP in adult and pediatric cases.

Hypothetical Scenarios

Scenario 1

Following sexual victimization, an adult female seeks post-rape care at HUEH. She enters the outpatient clinic and requests to be seen by the attending physician for a physical exam, yet fails to disclose her recent sexual assault to hospital personnel for fear of becoming stigmatized. Due to clinic over crowdedness she leaves HUEH premises only to return a few days later, likely beyond the recommended 72-hour period to receive ARV-PEP.

Scenario 2

Following sexual victimization an adult female seeks HIV testing at HUEH for fear she has been infected by her perpetrator, and asks to be directed to the VCT. However, this survivor is most likely unaware that an HIV test immediately post-rape would not indicate her status due to the rape. HUEH personnel, unaware of the recent sexual victimization, direct this survivor through a department as outlined in the VCT algorithm (Figure 3, Step 1). This survivor is then navigated to the VCT pre/post counseling session (Step 2), yet during the session the survivor fails to disclose her recent sexual victimization to the counselor because she anticipated discussing the assault with a physician.

Figure 3.

HIV Algorithm for Volunteer Counseling & Testing at HUEH

At this juncture (Step 3), for a non-disclosing survivor who tests HIV positive, she will be navigated towards Steps 4 through 9 per guidelines in the VCT Algorithm for HIV positive adults. However, for a non-disclosing survivor who tests HIV negative (or inconclusive), the VCT Algorithm directs the counselor to instruct the VCT client to “go home” then “return for follow-up testing in 3 months”. In this latter scenario because the survivor/client failed to disclose her sexual victimization the counselor is unaware that this VCT encounter should have been a baseline HIV test post-rape. Henceforth, the counselor fails to direct this survivor through the Medical Algorithm for victims of sexual assault.

Scenario 3

Following sexual victimization a female child seeks medical care at HUEH and is accompanied by a non-relative, who is not a legal guardian. This female child is in domestic servitude and severely disenfranchised. Her accompanier does not have the capacity to understand all of the complex medical issues, nor has the authorization to make medical decisions on the child’s behalf. As such the accompanier and child refuse HIV testing and seek treatment only for injuries and lesions.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the surveillance data provided by HUEH on the number of sexual assault survivors seeking care was not sufficiently rigorous. Known socio-demographic factors, and characteristics of the assault, that influence uptake and adherence to ARV-PEP were not systematically collected. The temporal link of post-rape service seeking with sexual victimization is also unknown, making it difficult to determine what proportion of survivors arrived beyond the 72-hour uptake period, or refused prophylaxis. It is also unknown what proportion of women refused HIV testing at presentation, or tested positive. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design is a limitation as we do not know the outcomes of sexual assault survivors who accepted ARV-PEP, nor do we know the seroconversion rates amongst these rape victims.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first empirical report on the uptake to antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis amongst female victims of sexual violence in Haiti, with three main study findings.

First, results from analyses of surveillance data show that girls under 18 years of age have extremely low uptake (38.4%) to ARV-PEP, and barriers to uptake in this study population are not well understood. Findings from interviews with HUEH personnel and contractors also suggest that non-relatives frequently accompany many of these young victims, which is not surprising as other adults [employers and older domestic servants] take care of them. Under these circumstances post-rape service seeking may be delayed for young victims, and refusal to accept HIV testing upon presentation is conceivable because the accompanier may not be capable or authorized to make medical decisions for the child. The issue of concern is that susceptibility to HIV transmission may be higher in young girls because they have a thinner vaginal epithelium compared to women25, and there may be reoccurring abuse by the same person over time that is not uncommon as the exploitation of Haitian children in servitude is well documented35–38.

Second, although surveillance data shows that uptake to ARV-PEP is significantly higher amongst adult survivors (60.1%; p<0.001), interviews with HUEH personnel suggest that many women fail to disclose their victimization for fear of being stigmatized, thus only seek HIV testing. A consequence of non-disclosure is that information on the importance of ARV-PEP is not imparted to the victim, nor is information shared on the availability of rape crisis counselors.

The literature suggests that failure to disclose might be explained by a number of factors. For instance, women experiencing assaults characterized by stranger rape, use of weapons, severe injury and greater victim resistance are more likely to disclose victimization to formal support sources39,40. Whereas, some women may not feel they deserve assistance because their offenders were known acquaintances, or these women self-blame because they were intoxicated during the time of the assault41.

Lastly, results from interviews conducted with in-house and contracted counselors suggest that mental health service seeking behavior was severely low in this study population, and defaulting on follow-up counseling was common. Unfortunately these are lost opportunities for the treatment of post-rape psychopathology42,43 like depression, distress and post-traumatic stress disorder, which are known to adversely influence adherence to antiretroviral treatments30–34,44. Noteworthy is that the low proportion of survivors seeking mental health services in this study is similar to findings in other studies conducted in western and resource-poor settings45,46. Literature reports also describe that sexual assault survivors are more likely to disclose to physicians following victimization to obtain testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases47 versus contacting a mental health professional48–50, which appears to be consistent with interview findings obtained from HUEH personnel.

In Haiti, predictors of mental health service seeking following sexual assault are unknown. Plausible explanations might include avoidant behavior as a way to protect themselves from the overwhelming emotional affect51,52; many Haitians are known to have negative attitudes towards mental health professionals, many Haitians also believe that mental illness is caused by supernatural forces53. Hence, cultural beliefs about mental illness and emotional reactions following rape might help to explain the underutilization and avoidance of mental health services in this study population.

Conclusions

Despite concerted efforts at the hospital and ministerial level to put into practice the national standards for the provision of post-rape care at the largest publicly funded health facility, study findings suggest a gap in tailored programming designed for the special needs of sexual assault survivors. Haiti has been a recipient of PEPFAR funding having received over $451 million between 2004 to 200954, and PEPFAR currently supports 80% of sites providing HIV services throughout the nation15, however adequate post-rape clinical programs for adult and pediatric survivors is lacking.

At HUEH the prioritization of funding and comprehensive interventions that align sexual violence, HIV prevention and mental health are crucial to support the timely uptake to ARV-PEP. In Haiti, this is a severely understudied area that warrants further investigation. Future research directions should focus on better understanding: (a) predictors of delayed presentation (beyond 72 hours) for adult and pediatric victims; (b) victim and organizational barriers for the uptake to ARV-PEP; (c) disclosure of sexual victimization for supportive services; (d) predictors of mental health service seeking behaviors; and (e) the clinical manifestation of post-rape psychopathology in this context.

Acknowledgments

During the conduct of this study LGM was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (T32 MH067555 and L60 MD002421-01) and Behavioral Science Research Institute, Inc.

References

- 1.Collings SJ, Bugwandeen SR, Wiles WA. HIV post-exposure prophylaxis for child rape survivors in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: who qualifies and who complies? Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:477–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilonzo N. Post-Rape Services in Kenya. Liverpool VCT and Care Kenya: 2003. http://www.preventgbvafrica.org/sites/default/files/resources/postrapeserviceskenya.pdf [Accessed October 12, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christofides NJ, Muirhead D, Jewkes RK, Penn-Kekana L, Conco DN. Women’s experiences of and preferences for services after rape in South Africa: interview study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2006;332:209–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38664.482060.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speight CG, Klufio A, Kilonzo SN, Mbugua C, Kuria E, Bunn JE, Taegtmeyer M. Piloting post-exposure prophylaxis in Kenya raises specific concerns for the management of childhood rape. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christofides NJ, Jewkes RK, Webster N, Penn-Kekana L, Abrahams N, Martin LJ. “Other patients are really in need of medical attention”–the quality of health services for rape survivors in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83:495–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn JO, Martin JN, Roland ME, Bamberger JD, Chesney M, Chambers D, Franses K, Coates TJ, Katz MH. Feasibility of postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) against human immunodeficiency virus infection after sexual or injection drug use exposure: the San Francisco PEP Study. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2001;183:707–14. doi: 10.1086/318829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelly JR, Nejuste P, Honore JG. L’Hopital Generale de l’Etat D’Haiti, MSPP, Direction Generale. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.James EC. The political economy of ‘trauma’ in Haiti in the democratic era of insecurity. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2004;28:127–49. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000034407.39471.d4. discussion 211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jefferson LR, Ralph RE, Thomas DQ, Miah E. Human Rights Watch and the National Coalition for Haitian Refugees. Washington, DC and New York, NY: 1994. Rape in Haiti: A Weapon of Terror. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson S. Haitian forum addresses trauma, domestic violence. The Bay State Banner. 2010 Aug 19 19;Aug 19 19;6(42) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taking Rapists to Court in Haiti. United Nations Population Fund; 2005. Accessed at http://www.unfpa.org/news/news.cfm?ID=1051. [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf [Accessed October 12, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JC, Martin LJ, Denny L. Rape and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: addressing the dual epidemics in South Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11:101–12. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haiti. Programme National de Lutte contre le SIDA (PNLS): Plan Strategique National Multisectoriel (2008–2012) Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Gourvernement de la Republique d’Haiti; 2008. Date Accessed: September 26, 2012 http://wwwaidstar-onecom/sites/default/files/prevention/resources/national_strategic_plans/Haiti_2008-2012_Frenchpdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walldorf JA, Joseph P, Valles JS, Sabatier JF, Marston BJ, Jean-Charles K, Louissant E, Tappero JW. Recovery of HIV service provision post-earthquake. Aids. 2012;26:1431–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328352d032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullman SE. Mental health services seeking in sexual assault victims. Women & Therapy. 2007;30(1–2):61–84. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG. Service utilization and help seeking in a national sample of female rape victims. Psychiatric Services. 2008 Dec;59(12):1450–1457. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1450. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamothe NN. (Personal Communication). L’Hopital Generale de l’Etat D’Haiti, MSPP, Direction Generale. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Berk GE, Frissen PH, Regez RM, Rietra PJ. Evaluation of the rapid immunoassay determine HIV 1/2 for detection of antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2003;41:3868–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3868-3869.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramalingam S, Kannangai R, Raj AA, Jesudason MV, Sridharan G. Rapid particle agglutination test for human immunodeficiency virus: hospital-based evaluation. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2002;40:1553–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1553-1554.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gostin LO, Lazzarini Z, Alexander D, Brandt AM, Mayer KH, Silverman DC. HIV testing, counseling, and prophylaxis after sexual assault. [see comment] JAMA. 1994;271:1436–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurie P, Miller S, Hecht F, Chesney M, Lo B. Postexposure prophylaxis after nonoccupational HIV exposure: clinical, ethical, and policy considerations. JAMA. 1998;280:1769–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bamberger JD, Waldo CR, Gerberding JL, Katz MH. Postexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection following sexual assault. Am J Med. 1999;106:323–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberg GA. Postexposure prophylaxis against human immunodeficiency virus infection after sexual assault. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2002;21:959–60. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200210000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Havens PL, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric A Postexposure prophylaxis in children and adolescents for nonoccupational exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1475–89. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ, Auerbach JD, Veronese F, Struble KA, Cheever L, Johnson M, Paxton LA, Onorato IM, Greenberg AE. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roland ME. Postexposure prophylaxis after sexual exposure to HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:39–46. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328012c5e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beaussejours P, Coicou N, Henrys K. Anecdotal reports of sexual violence reported in Port-au-Prince. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: 2009. Personal Communication with Psychologists at Medecin du Monde-(France) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ullman SE. Mental Health Services Seeking in Sexual Assault Victims. Women & Therapy. 2007;30:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safren SA, Gershuny BS, Hendriksen E. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress and Death Anxiety in Persons with HIV and Medication Adherence Difficulties. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17 doi: 10.1089/108729103771928717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. The Differential Impact of PTSD and Depression on HIV Disease Markers and Adherence to HAART in People Living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2006 May;10(3):253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sledjeski EM, Delahanty DL, Bogart LM. Incidence and Impact of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Comorbid Depression on Adherence to HAART and CD4-super(+) Counts in People Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005 Nov;19(11):728–736. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.728. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, Vella S, Robbins GK. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2004;8:141–50. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marc LG, Testa MA, Walker AM, Robbins GK, Shafer RW, Anderson NB, Berkman LF. Educational attainment and response to HAART during initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dominguez KL. Management of HIV-infected children in the home and institutional settings. Care of children and infections control in schools, day care, hospital settings, home, foster care, and adoption. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2000;47:203–39. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson L, Kelly EJ, Kinnunen ZK, Minnesota Lawyers International Human Rights Committee . Restavek : child domestic labor in Haiti. Minneapolis, Minn: The Committee; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cadet J-R, Cadet Nassano C. Restavec: From Haitian Slave Child to Middle-Class American Texas. University of Texas Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martsolf DS. Childhood maltreatment and mental and physical health in Haitian adults. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:293–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filipas HH, Ullman SE. Social reactions to sexual assault victims from various support sources. Violence Vict. 2001;16:673–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell R, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Wasco SM, Barnes HE. Social reactions to rape victims: healing and hurtful effects on psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence Vict. 2001;16:287–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starzynski LL, Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Long LM, Long SM. What factors predict women’s disclosure of sexual assault to mental health professionals? Journal of Community Psychology. 2007 Jul;35(5):619–638. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Resnick H, Acierno R, Waldrop AE, King L, King D, Danielson C, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick D. Randomized controlled evaluation of an early intervention to prevent post-rape psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007 Oct;45(10):2432–2447. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.002. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Resnick H, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Holmes M. Description of an Early Intervention to Prevent Substance Abuse and Psychopathology in Recent Rape Victims. Behavior Modification. 2005 Jan;29(1):156–188. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270883. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marc LG, Wang MM, Testa MA. Psychometric evaluation of the HIV symptom distress scale. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1432–41. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.656567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frazier P, Rosenberger S, Moore N. Correlates of service utilization among sexual assault survivors; Poster presented at annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; 2000; Washington DC. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carries S, Muller F, Muller FJ, Morroni C, Wilson D. Characteristics, treatment, and antiretroviral prophylaxis adherence of South African rape survivors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:68–71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31813e62f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Resnick HS, Holmes MM, Kilpatrick DG, Clum G, Acierno R, Best CL, Saunders BE. Predictors of post-rape medical care in a national sample of women. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:214–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golding JM, Siegel JM, Sorenson SB, Burman MA, Stein JA. Social support sources following sexual assault. Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:92–107. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koss MP, Koss PG, Woodruff WJ. Deleterious Effects of Criminal Victimization on Women’s Health and Medical Utilization. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:342–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimerling R, Calhoun KS. Somatic symptoms, social support, and treatment seeking among sexaul assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:333–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frazier PA, Burnett JW. Immediate coping strategies among rape victims. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1994;72:633–9. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer CB, Taylor SE. Adjustment to rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;30:1226–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desrosiers A., St Treating Haitian patients: Key cultural aspects. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2002;56:508–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.PEPFAR. Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Haiti. 2011 http://www.pepfar.gov/countries/haiti/index.htm [Accessed October 12, 2012]