Summary

Exercise performance in individuals with cystic fibrosis has been shown to be related to the degree of pulmonary dysfunction and undernutrition and genetic profile. The aim of this study was to examine these relationships in young children with cystic fibrosis. The participants were 64 children ages 8 to 11 years (M = 9.3, SD = 0.9) with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency recruited from 13 different U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Centers. Assigned to one of three groups by ΔF508 status: ΔF508/ΔF508 homozygous, ΔF508/Other heterozygous, and Other/Other, growth, nutritional and pulmonary status, and exercise performance were measured. Differences in exercise performance, pulmonary function, and nutritional status were not observed among the three groups. However, undernutrition and decreased pulmonary function were associated with measures of exercise performance. These results imply no effect of ΔF508 status on overall functional capacity during preadolescence in children with cystic fibrosis. Rather, the degree of pulmonary disease and undernutrition were associated with functional performance.

Keywords: aerobic capacity, pulmonary disease, ΔF508, nutritional status

Since the identification of the genetic defect that causes cystic fibrosis, investigators have worked to correlate genotype with the clinical consequences (Boat, Welsh, & Beaudet, 1989; Kerem, Rommens, Buchanan, Markiewicz, Cox, Chakravarti, Buchwald, & Tsui, 1989; Johansen, Nir, Hoiby, Kocj, & Schwartz, 1991; Kristidis, Bozon, Corey, Mariewicz, Rommens, Tsui, & Durie, 1992; Sheppard, Rich, Ostegaard, Gregory, Smith, & Welsh, 1993; Kerem & Kerem, 1996; Vanscoy, Blackman, Collaco, Lai, Naughton, Algire, McWilliams, Beck, Hoover-Fong, Hamosh, Cutler, & Cutting, 2007). The most common mutation, ΔF508, accounts for more than seventy percent of cystic fibrosis variants worldwide. However, more than 1000 additional mutant alleles have been reported to the Cystic Fibrosis Genetic Consortium, all of which are uncommon or rare (Zielenski, 2000). The molecular mechanism of this genetic mutation is disruption of transmembrane regulatory proteins that control chloride transport in the epithelial cells of the lungs and pancreas. Therefore, the extent to which various cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator alleles contribute to clinical variation in cystic fibrosis can be classified according to their predicted effects on cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulation (Zielenski, 2000). In a five class sytem, mutations belonging to classes I, II, and III are predicted to have severe pulmonary and pancreatic consequences due to the absence of protein at the apical membrane. Mutations belonging to classes IV and V are expected to have milder consequences because while present, transmembrane regulator function is reduced. However, the clinical consequences of specific cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator mutations cannot always be assumed or even predicted since cystic fibrosis disease phenotypes in different organs are under the influence of many secondary factors, including the genetic background of the individual and environmental factors to which each patient is exposed (Zielenski, 2000). For example, patients homozygous for the ΔF508 mutation (Class I) tend to have earlier diagnosis, are more likely to be pancreatic insufficient, and have higher sweat chloride levels (Zielenski, Rozmahel, Bozon, Kerem, Grzelczak, Riordan, Rommens, & Tsui, 1991; Tsui, 1992). However, the severity of the pulmonary component in these patients disease is highly variable, independent of genotype. (Santis, Osborne, Knight, Hodson, & Ramsay, 1990; Sheppard, et al., 1993).

Exercise performance and fitness in people with cystic fibrosis are areas being completely revisited in the broader scope of genetics, particularly as it relates to clinical outcome. While physical fitness has been shown to be a good indicator of overall functioning and an important predictor of survival in cystic fibrosis, the relevance of exercise to cystic fibrosis is complex. Exercise capacity is directly related to pulmonary function and is associated with prognosis and survival (Nixon, Orenstein, Kelsey, & Doershuk, 1992). However, cystic fibrosis is often accompanied by a state of undernutrition marked by poor absorption of fats, vitamin D, and calcium, which may affect skeletal and respiratory muscle function, as well as, bone health. Undernutrition is another significant predictor of mortality in individuals with cystic fibrosis (Moorcroft, Dodd, & Webb, 1997). Therefore, the physiologic benefits of physical activity are important in the cystic fibrosis population as exercise enhances energy, skeletal and respiratory muscle strength and endurance, bone mass, and the ability to participate with peers in sports.

The relationship between genetics and exercise in children with cystic fibrosis is less clear. Adolescents with moderate lung disease associated with cystic fibrosis, and at least one copy of the ΔF508 mutation, have been shown to have lower exercise capacity based on cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator mutation class compared to those with non-ΔF508 genotypes (Selvadurai, McKay, Blimkie, Cooper, Mellis, & Van Asperen, 2002). In another study, no significant differences were found in exercise capacity between adolescents who were homozygous or heterozygous for the ΔF508 gene mutation (Kaplan, Moccia-Loos, Rabin, & McKey, 1996). The influence of ΔF508 status on these outcome measures in the preadolescent population has not been explored. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the relationships between exercise performance, nutritional status, and pulmonary function in eight to eleven year old children, according to ΔF508 status.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were children with cystic fibrosis from 13 different cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Ninety one were identified as eligible to participate in the study. Children with severe lung disease (forced expiratory volume in one second less than 40 % of norm) and complications of cystic fibrosis (e.g., significant liver disease or uncontrolled insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) were excluded from the study. Also excluded were children with significant developmental delay (e.g., autism, cerebral palsy, or mental retardation). Aerobic exercise performance, pulmonary function, and anthropometric data were assessed during a single day of testing at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia General Clinical Research Center while in a state of good health. Genetic data were collected from a review of each subject's medical record or obtained as part of the study. Laboratory protocols for DNA extraction and mutation detection are published elsewhere (Chehab & Wall, 1992). Informed written consent was obtained from the parents or guardians, while written assent was obtained from each child prior to participation in the study. The Institutional Review Board at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia approved the study.

Materials and Procedures

Each subject was assigned to a cystic fibrosis mutation group based on the presence of ΔF508 (Table 1). The Shwachman score, which combines growth, body habitus measures, and clinical status parameters including the Brasfield chest x-ray score, was used to compare the disease severity of the subjects (Shwachman & Kulczvcki, 1958).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Subjects According to ΔF508 Status.

| Variable | All (n = 64) | Genotype Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| ΔF508/ΔF508 (n = 36) | ΔF508/Other (n = 19) | Other/Other (n = 9) | p value | ||

| Demographic | |||||

| Age, yr | 9.3 (0.9) | 9.4 (0.8) | 9.1 (1.2) | 9.2 (1.0) | .48 |

| Male:Female | 33 : 31 | 16 : 20 | 11 : 8 | 5 : 4 | .67 |

| Shwachman score | 86.4 (4.9) | 86.9 (3.8) | 85.4 (6.3) | 86.5 (6.1) | .55 |

| Nutritional | |||||

| HT-z | -0.5 (1.1) | -0.3 (1.1) | -0.6 (0.9) | -0.5 (0.4) | .61 |

| WT-z | -0.4 (1.2) | -0.3 (1.1) | -0.5 (1.1) | -0.3 (1.6) | .76 |

| BMI-z | -0.2 (1.1) | -0.1 (1.1) | -0.3 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | .72 |

| FFM, kg | 24.2 (4.3) | 24.7 (4.1) | 23.2 (4.1) | 24.2 (5.1) | .46 |

| Pulmonary | |||||

| FVC, % norm | 98 (14) | 97 (14) | 98 (13) | 103 (15) | .54 |

| FEV1, % norm | 91(15) | 90 (16) | 92 (13) | 94 (15) | .78 |

Note. Data are represented as mean (SD). HT-z: height z-score; WT-z: weight z-score; BMI-z: body mass index z-score; FFM: fat free mass; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second.

19 subjects were ΔF508/other, including 5 subjects with ΔF508/unknown, 3 subjects with ΔF508/G551D, 3 subjects with ΔF508/W1282X, 2 subjects with ΔF508/1717-1G>A, 2 subjects with ΔF508/2789+5G>A, and 1 each with ΔF508/3120+1G>A, ΔF508/621+1G>T, ΔF508/A455E, and ΔF508/R347P.

9 Subjects were Other/Other, including 2 with unknown/unknown, and 1 each with 2183delAA>G/G551D, unknown/G551D, N1303K/unknown, R334W/unknown, V520F/unknown, unknown/V520F, and W1282X/W1282X

Resting Lung Mechanics

Pulmonary function was evaluated immediately prior to exercise testing using standard methods for spirometry, lung volumes, and conductance (American Thoracic Society, 1994). Forced expiratory volume in one second and forced vital capacity were measured and compared with age and gender matched reference values (Hankinson, Odencrantz, & Fedan, 1999). Ventilatory reserve at peak exercise was estimated using the previously described method by Stein, Selvadurai, & Coates (2003).

Cycle Ergometry

All subjects were exercised to maximal volition using an electronically-braked cycle ergometer (SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA). Maximal volition was defined as a maximum respiratory exchange ratio greater than 1.00 or a rise in the respiratory exchange ratio to greater than 1.30 during the first two minutes of the recovery phase. The protocol consisted of three minutes of pedaling in an unloaded state followed by a ramp increase in work rate to maximal exercise. The steepness of the ramp protocol was determined by subject's weight in kilograms and was designed to achieve predicted peak work rate (watts) in ten to 12 minutes of cycling (Rowland, 1993).

Cardiac, metabolic, and ventilatory monitoring

Cardiac rhythm, blood pressure, and systemic arterial oxygen saturation were monitored continuously and recorded intermittently throughout each study. Metabolic and ventilatory data were obtained throughout the exercise test and for the first two minutes of recovery on a breath-by-breath basis using a metabolic cart (SensorMedics V29, Yorba Linda, CA). Parameters measured included minute oxygen consumption, minute carbon dioxide production, minute ventilation, and the respiratory exchange ratio. Ventilatory anaerobic threshold was measured by the V-slope method (Beaver, Wasserman, & Whipp, 1986). Data were compared to healthy age and sex matched children using the same exercise protocol as reported by Cooper, Weiler-Ravell, Whipp, & Wasserman (1984).

Body habitus

All anthropometric measurements were obtained in triplicate using the methods described by Lohman, Roche, & Matorell (1988). Height and weight were recorded using a digital scale accurate to 0.1 kilogram (Scaltronix, White Plains, NY) and a stadiometer accurate to 0.1 centimeter (Holtain, Crymych, UK). A skinfold caliper (Holtain) was used to measure the biceps, triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac skinfolds on the right side. Using age- and sex-specific equations, percentage of body fat, fat mass in kilograms, and fat free mass in kilograms were calculated from the four skinfolds (Brook, 1971; Durnin & Womersly, 1974; Lohman, et al., 1988). Z-scores for height, weight, and body mass index were calculated based on Centers for Disease Control growth charts (Frisancho, 1990).

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis proceeded in three discrete steps. First, descriptive statistics for all variables in the data set were computed using traditional measures of central tendency and variability. Second, a total of 19 different analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were specified and tested, specifically to test for differences across three ΔF508 status classifications: ΔF508/ΔF508, ΔF508/Other, and Other/Other. Outcomes were organized into six different areas of clinical relevance: demographics, nutritional, pulmonary, cardiac, metabolic and ventilatory, and musculosketal.

Third, two different sets of linear regression models were specified and tested, one set for each of two exercise related outcomes: peak oxygen consumption and peak physical working capacity. In each case, ten different single covariate models were specified and tested, using the nine covariates listed in Table 1 as well as ΔF508 status. Any single covariate models with a p-value less than 0.10 were considered as candidates for inclusion in one of the two multiple covariate equations. Due to the multiplicity of tests conducted, and the increased likelihood of a Type I error rate given the correlated nature of the data, hypothesis-wise error rates were adjusted to account for the 41 different models tested using Tukey, Ciminera, and Heyse's adjustment for multiple, moderately correlated endpoints (αadj = .008) (Zhang, Quan, Ng, & Stepanavage, 1997). All analyses were computed using Statistical Analysis Software 9.1.

Results

Demographics

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the entire cohort and according to ΔF508 status are listed in Table 1. Of the 91 children eligible for the study, 64 (33 male, 31 female; M age = 9.3, SD = 0.9 years) volunteered to participate in the exercise portion of the study between August 2002 and October 2004. The 27 subjects who did not participate in the exercise protocol did not differ significantly from those who did in age and sex, growth and nutritional status, or pulmonary status. There was a relatively narrow range of disease severity as measured by the Shwachman score with a mean of 86.4, SD = 4.9, range 72.2 to 95.7. All subjects were diagnosed as pancreatic insufficient.

At the time of this study, genotype analysis was able to identify approximately 100 different common alleles for cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulatory protein. Therefore, patients' data were grouped by partial genotype (homozygous and heterozygous for ΔF508) and by specific genotypes when available; there were not enough specifically genotyped participants for statistical analysis. In 13 of the subjects, one or both cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator alleles were not readily identified. Subjects with non-ΔF508 mutations were pooled as “Other” for subsequent analyses. The proportions of ΔF508 status were 0.56 (ΔF508/ΔF508), 0.30 (ΔF508/Other), and 0.14 (Other/Other).

Body Habitus

Measures of body habitus are also displayed in Table 1. Body habitus variables were suboptimal for the entire study group, as measured by height z-score (M = -0.5, SD = 1.1), weight z-score (M = -0.4, SD = 1.2), and body mass index z-score (M = -0.2, SD = 1.1), and did not differ by ΔF508 status. Lean tissue for the entire study group, as measured by FFM was 24.2 kilograms (SD = 4.3) and did not differ by ΔF508 status.

Pulmonary Function

Resting indices of pulmonary function are also displayed in Table 1. As a group, forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in one second were 98 (SD = 14) % of predicted (range 72 to 138 % of predicted) and 91 (SD = 15) % of predicted (range 67 to 128 % of predicted), respectively. Significant differences were not observed between the three groups in forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in one second.

Cardiopulmonary Performance

Raw and percent of predicted values for the entire cohort and by ΔF508 status are displayed in Table 2. All subjects were felt to have achieved maximal aerobic capacity based on an respiratory exchange ratio greater than 1.00. Chronotropy (heart rate) was not felt to be impaired in any subject. Overall, peak oxygen comsumption was 95 (SD = 20) % of predicted for normal age- and sex-matched children (Cooper, et al., 1984). The oxygen consumption at the ventilatory anaerobic threshold is reported in 50 subjects for whom it was accurately measured by the V-slope method. The ventilatory anaerobic threshold for the group was 58 (SD = 9) % of peak oxygen consumption. This ratio was within the 54 to 61 % range reported for healthy children (Cooper, et al., 1984; Wasserman, Hansen, Sue, Casaburi, & Whipp, 1999). No parameter of cardiopulmonary exercise performance was found to be significantly associated with ΔF508 status.

Table 2.

Exercise Performance of Subjects According to Genotype.

| Variable | All (n = 64) | Genotype Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| ΔF508/ΔF508 (n = 36) | ΔF508/Other (n = 19) | Other/Other (n = 9) | p value | ||

| Cardiac | |||||

| Peak HR, b·min-1 | 192.3 (10.1) | 192.4 (10.2) | 193.1 (8.6) | 190.1 (13.4) | .68 |

| Peak HR, % pred | 92 (5) | 96 (5) | 97 (4) | 95 (6) | .66 |

| Metabolic and Ventilatory | |||||

| Peak VO2, ml·kg-1·n-1 | 38.1 (8.5) | 38.1 (8.3) | 38.2 (8.8) | 38.1 (9.9) | .99 |

| Peak VO2, % pred | 95 (20) | 95 (19) | 95 (21) | 95 (25) | .99 |

| VAT, ml·kg-1·min-1 | 23.4 (4.2) | 22.8 (5.6) | 23.7 (4.8) | 24.2 (3.7) | .68 |

| VAT, % of peak VO2 | 58 (9) | 60 (4) | 58 (5) | 57 (7) | .65 |

| RER, VCO2/VO2 | 1.15 (0.07) | 1.15 (0.08) | 1.14 (0.08) | 1.14 (0.05) | .46 |

| VR, % | 21.1 (8.4) | 18.4 (10.1) | 23.2 (10.8) | 20.4 (5.2) | .21 |

| Musculoskeletal | |||||

| PWC, watts | 83.1 (19) | 85.1 (19.7) | 80.5 (16.2) | 83.2 (18.1) | .61 |

| PWC, % of pred | 97 (20) | 95 (19) | 98 (23) | 96 (17) | .70 |

Note. Data are represented as mean (SD). HR: heart rate; VO2: minute oxygen consumption; VAT: ventilatory anaerobic threshold;; RER: respiratory exchange ratio; VR: ventilatory reserve; PWC: physical working capacity.

Musculoskeletal Performance

Physical working capacity, as measured by maximal work rate in watts and percentage of predicted values are also reported in Table 2. On average the entire study cohort achieved 97% of predicted values for age and sex (Rowland, 1993). Five subjects (8%) had work rates below 80% of the predicted value. All had peak oxygen consumption within normal range suggesting a mechanical inefficiency (i.e., pedaling efficiency) as the cause of low physical working capacity rather than an impairment of aerobic capacity. Significant differences in physical working capacity were not observed between the three groups, and thus unrelated to ΔF508 status.

Determinants of Exercise Performance

Single covariate models

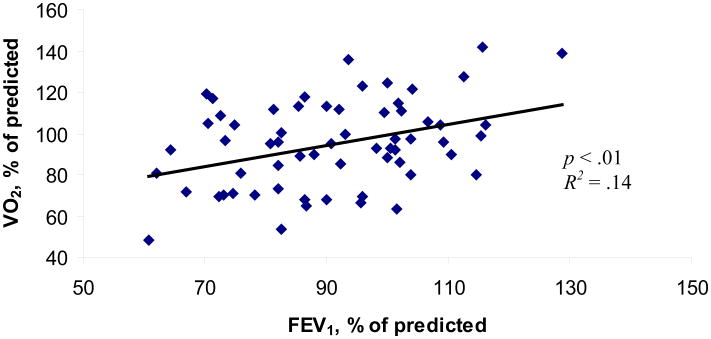

Single covariate models are presented in Table 3. Z-scores for body mass index and weight were not found to be associated with ΔF508 status; however, both were found to be significantly associated with exercise performance as measured by peak oxygen consumption (R2 = .11, p < .01 and R2 = .09, p = .02, respectively) and PWC (R2 = .08, p = .02 and R2 = .11, p < .01). Height z-score was not associated with any parameter of exercise performance. In addition, while the relationship between fat free mass was not a statistically significant predictor of peak oxygen comsumption, it was a statistically significant predictor of physical working capacity (R2 = .15, p < .01). Finally, a statistically significant associate was found between the percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in one second and exercise performance, measured by peak oxygen consumption (R2 = .14, p < .01) [see Figure 1] and physical working capacity (R2 = .06, p < .05).

Table 3. Single Covariate Models.

| Covariate | SS | F | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak VO2 Model | ||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | .88 | * |

| Gender | 0.03 | 0.14 | .71 | * |

| ΔF508 status | 0.03 | 0.06 | .93 | * |

| Shwachman score | 0.64 | 0.02 | .87 | * |

| HT-z | 2.17 | 1.67 | .20 | * |

| WT-z | 8.57 | 6.01 | .02 | 0.09 |

| BMI-z | 9.19 | 7.81 | <.01 | 0.11 |

| FFM | 22.67 | 2.82 | .11 | * |

| FVC | 0.26 | 1.45 | .23 | * |

| FEV1 | 1928.12 | 9.43 | <.01 | 0.14 |

| PWC Model | ||||

| Age | 1.41 | 1.49 | .22 | * |

| Gender | 0.25 | 0.98 | .32 | * |

| ΔF508 status | 0.09 | 0.17 | .67 | * |

| Shwachman score | 1.61 | 0.06 | .80 | * |

| HT-z | 0.53 | 0.38 | .53 | * |

| WT-z | 11.44 | 8.29 | <.01 | 0.11 |

| BMI-z | 6.94 | 5.72 | .02 | 0.08 |

| FFM | 173.63 | 11.14 | <.01 | 0.15 |

| FVC | 0.37 | 2.04 | .15 | * |

| FEV1 | 905.44 | 4.11 | .04 | 0.06 |

Note.

Value < 0.001. VO2: minute oxygen consumption; HT-z: height z-score; WT-z: weight z-score; BMI-z: body mass index z-score; FFM: fat free mass; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; PWC: physical working capacity.

Figure 1.

Relationship between % normative FEV1 and % of predicted peak VO2.

Multiple covariate models

To test for synergistic effects, covariates with p < .10 were entered into multiple covariate regression model to arrive at the best fitting model for each of the three primary outcomes of exercise performance (Table 4). Analogous models were tested for the primary exercise related outcomes, peak oxygen consumption and physical working capacity. Statistically significant covariates for the peak oxygen consumption were forced expiratory volume in one second, fat free mass, and body mass index z-score (p < .01). The strongest predictors of musculoskeletal performance, as measured by physical working capacity, were forced expiratory volume in one second and fat free mass (p = .02).

Table 4. Multiple Covariate Models.

| Covariate | β Coef | SE | t | p | Model p value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak VO2 Model | <0.01 | 0.25 | ||||

| FEV1 | 12.03 | 3.65 | 3.29 | <0.01 | ||

| FFM | -0.67 | 0.38 | 1.75 | 0.08 | ||

| BMI-z | -2.21 | 1.12 | 1.95 | 0.05 | ||

| Intercept | 21.83 | 21.72 | 1.01 | |||

| PWC Model | 0.02 | 0.27 | ||||

| FEV1 | 19.31 | 8.53 | 2.26 | 0.03 | ||

| FFM | -2.68 | 0.96 | 2.79 | 0.07 | ||

| Intercept | 64.90 | 12.88 | 5.04 |

Note. VO2: minute oxygen consumption; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FFM: fat free mass; BMI-z: body mass index z-score; PWC: physical working capacity.

Discussion

These results suggest that exercise performance in preadolescent children with mild lung disease associated with cystic fibrosis was not related to ΔF508 status. Growth, nutritional, and pulmonary status were also unrelated to ΔF508 status in these children.

Various attempts have been made to correlate genetic profile with clinical features, such as pulmonary status, nutritional status, and prognosis in cystic fibrosis (Boat et al. 1989; Kerem et al., 1989; Johansen et al., 1991; Kristidis et al., 1992; Vanscoy et al., 1992; Sheppard et al., 1993; Kerem & Kerem, 1996). However, less is known about the effects of genotype on physical performance. Kaplan and colleagues did not find differences in nutritional status and exercise performance between adolescents who were homozygous and heterozygous for the ΔF508 mutation (Kaplan et al., 1996). The results of their study were limited by the relatively small number of subjects (N = 35).

Previously, the molecular mechanisms by which genetic mutations disrupt cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator have been proposed (Zielenski,et al., 1991; Tsui, 1992; Zielenski, 2000). Categorizing these mechanisms into five separate classes (Classes I-V) may provide a better understanding of the pathophysiology of the cystic fibrosis disease process. Selvadurai and colleagues assessed the effect of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator class on exercise performance and nutritional status in adolescents with moderate lung disease and a mix of pancreatic status (Selvadurai, et al., 2002). Significant differences were noted in peak aerobic capacity between subjects with “severe” mutations (Class I and II) and those with “less severe” mutations (Class III-V). Although significant differences in nutritional status, as measured by body mass index, were observed between Class I and II subjects and Class III-V subjects, nutritional status could not completely explain the differences in exercise performance, possibly because, clinically, the nutritional status of these subjects was adequate. However, no standard measure of growth and nutritional status (i.e., z-scores) were presented although there was a wide range of age. Therefore, the effect of growth and nutritional status on parameters of exercise performance can not be completely ruled out. No association between genotype and lung function was noted. Selvadurai and colleagues concluded that exercise performance could only be explained by the molecular mechanisms conferred by the particular genetic mutation. Considering the findings of the present study, differences between ΔF508 status groups may have been obscured if undetected mutations were associated with more severe disease. Further identification of remaining cystic fibrosis mutations may lead to improved explanation of clinically evident heterogeneity in the future.

Results from this study indicate the degree by which aerobic exercise performance is limited will depend on the severity of lung disease and undernutrition. However, because these two factors often occur simultaneously in cystic fibrosis disease, it has been difficult to determine which of the two is the cause of reduced exercise performance (Godfrey & Mearns, 1971; Lands, Heigenhauser, & Jones, 1992; Rowland, 1993). In this study, pulmonary function and nutritional status were directly related to exercise performance. However, the variability (Figure 1) in peak oxygen consumption for any given value of forced expiratory volume in one second and the adequate ventilatory reserve noted at peak exercise may imply peripheral muscle function, and hence nutritional status, may be a stronger indicator of exercise performance.

De Meer and colleagues reported from their study in 15 children with moderately severe cystic fibrosis that aerobic power was associated with the percentage of fat-free mass (DeMeer, Jeneson, Gulmans, van der Laag, & Berger, 1995). They concluded that cellular abnormalities (oxidative mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate synthesis disturbances), and thus, inefficient energy production and utilization resulted in poor cycling efficiency and decreased aerobic power. Others have found similar results (Moser, Tirakitsoontorn, Nussbaum, Newcomb, & Cooper, 2000). However, in one study of adolescents with mild-to-moderate cystic fibrosis, the relationship between nutritional status and aerobic power was not found (Boas, Joswiak, Nixon, Fulton, & Orenstein, 1996).

In light of the importance of using exercise performance as a prognostic factor (Nixon, et al., 1992), lack of any appreciable effect of the ΔF508 mutation on exercise performance in the present study may be indirect evidence of a lack of effect of the specific mutation on prognosis that cannot be otherwise gained by traditional diagnostic methods. The present subjects with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency had mild growth failure and mild lung disease. The findings suggest that both deficits in nutritional status and pulmonary status may effect aerobic power in young children with cystic fibrosis, independent of ΔF508 status. These results identify the need to collectively include measures of aerobic exercise performance, nutritional status, and pulmonary status, rather than using genotype to estimate functional outcome in children with cystic fibrosis. Continued efforts to identify all genetic mutant alleles associated with cystic fibrosis disease and multicentered cooperation are necessary to obtain a large enough sample of patients to have sufficient data for each mutation and subsequent analyses on clinical outcome.

Study Limitations

Subjects enrolled into this study were recruited from 13 different United States Cystic Fibrosis Centers, which may be more representative of the general cystic fibrosis population. However, this does not rule out different cystic fibrosis treatment strategies among centers as a possible confounding variable in the health status of the subjects. Twenty-seven of the 91 eligible subjects voluntarily declined involvement in the study usually due to the extra time required for weekend studies or the distance to travel was a burden. However, these subjects were not significantly different in age, sex, pulmonary function, or nutritional status from those who did participate in exercise testing. Additionally, the relatively “normal” measures of pulmonary function found in the cohort are consistent with those reported for age and sex in the United States Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2006). Therefore, there does not appear to be any significant selection bias. Lastly, genotype analysis during the period in which this study was conducted was limited by the inability to identify more alleles for cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator. While no differences were found between ΔF508 status and exercise performance, pulmonary and nutritional status, further classification according to the molecular mechanisms conferred by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator mutation (Class I-V) may have revealed more profound results.

Conclusions

Exercise performance in young children with cystic fibrosis has not been well characterized. Genotype and its effect on functional outcome, particularly exercise performance, have had even less attention in younger individuals with cystic fibrosis. The present study showed that overall exercise performance was preserved in a large sample of preadolescent children with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency, independent of genotype. Rather, individuals with poorer nutritional status, and in particular, deficits in fat free mass, as well as decreased pulmonary function, may be at risk for lower functional capacity that might not be detected in the resting state. Adding cardiopulmonary exercise evaluations to serial evaluations of growth, nutritional, and pulmonary status in young children with cystic fibrosis may provide additional information about important functional implications of declining pulmonary function and nutritional status, and perhaps, this identifies the need for earlier intervention.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant Number UL1-RR-024134 from the National Center for Research Resources and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

References

- American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry, update. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting the anaerobic threshold during exercise and recovery in man. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1986;60:2020–2027. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boas SR, Joswiak ML, Nixon PA, Fulton JA, Orenstein DM. Factors limiting anaerobic performance in adolescent males with cystic fibrosis. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1996;28:291–298. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boat TF, Welsh MJ, Beaudet AL. Cystic Fibrosis. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. 6th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1989. pp. 2649–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Brook CGD. Determination of body composition of children from skinfold measurements. Archives of Disease in Children. 1971;46:182–84. doi: 10.1136/adc.46.246.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab FF, Wall J. Detection of multiple cystic fibrosis mutations by reverse dot blot hybridization. Human Genetics. 1992;89:163–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00217117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DM, Weiler-Ravell D, Whipp BJ, Wasserman K. Aerobic parameters of exercise as a function of body size during growth in children. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1984;56:628–34. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Patient Registry Annual Report. Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Meer K, Jeneson JA, Gulmans VA, van der Laag J, Berger R. Efficiency of oxidative work performance of skeletal muscle in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 1995;50:980–93. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.9.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durnin JVGA, Womersly J. Body fat assessment from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness measurements on 481 men and women aged 16 to 72 years. British Journal of Nutrition. 1974;32:77–97. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisancho A. Anthropometric standards for assessment of growth and nutritional status. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Godrey S, Mearns M. Pulmonary function and response to exercise in cystic fibrosis. Archives of Disease in Children. 1971;46:144–151. doi: 10.1136/adc.46.246.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen HK, Nir M, Hoiby N, Kocj C, Schwartz M. Severity of cystic fibrosis in patient homozygous and heterozygous for delta F508 mutation. Lancet. 1991;337:631–634. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92449-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan TA, Moccia-Loos G, Rabin M, McKey RM. Lack of effect of delta F508 mutation on aerobic capacity in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;6:226–231. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199610000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E, Kerem B. Genotype-phenotype correlations in cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1996;22:387–395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199612)22:6<387::AID-PPUL7>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 1989;245:1073–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristidis P, Bozon D, Corey M, Markiewicz D, Rommens J, Tsui LC, Durie P. Genetic determination of exocrine pancreatic function in cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1992;50:1178–1184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lands LC, Heigenhauser GJF, Jones NL. Analysis of factors limiting maximal exercise performance in cystic fibrosis. Clinical Scieince. 1992;83:391–97. doi: 10.1042/cs0830391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman TG, Roche AR, Matorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moorcroft AJ, Dodd ME, Webb AK. Long-term change in exercise capacity, body mass, and pulmonary function in adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1997;111:338–343. doi: 10.1016/s0012-3692(15)52531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser C, Tirakitsoontorn P, Nussbaum E, Newcomb R, Cooper DM. Muscle size and cardiorespiratory response to exercise in cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;162:1823–1827. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.2003057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF, Doershuk CF. The prognostic value of exercise testing in patients with cystic fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;327:1785–1788. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212173272504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland T. Pediatric Laboratory Exercise Testing. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Santis G, Osborne L, Knight R, Hodson ME, Ramsay M. Genetic influences on pulmonary severity in cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1990;335:294–295. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90114-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvadurai HC, McKay KO, Blimkie CJ, Cooper PJ, Mellis CM, Van Asperen PP. The relationship between genotype and exercise tolerance in children with cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002;165:762–765. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2104036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Rich DP, Ostegaard LS, Gregory RJ, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Mutations in CFTR associated with mild-disease-form Cl- channels with altered pore properties. Nature. 1993;362:160–164. doi: 10.1038/362160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shwachman E, Kulczycki M. Clinical evaluation and grading criteria for patients with cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Disease in Children. 1958;6:96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Stein R, Selvadurai H, Coates A. Determination of maximal voluntary ventilation in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2003;35:467–471. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui LC. The spectrum of cystic fibrosis mutations. Trends in Genetics. 1992;8:392–398. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90301-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanscoy LL, Blackman SM, Collaco JM, Lai T, Naughton K, Algire M, McWilliams R, Beck S, Hoover-Fong J, Hamosh A, Cutler D, Cutting GR. Heritability of lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175:1036–1043. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1164OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Casaburi R, Whipp BJ. 3rd. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. Principals of exercise testing and interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Quan J, Ng J, Stepanavage ME. Some statistical methods for multiple endpoints in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1997;18:204–221. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielenski J. Genotype and phenotype in cystic fibrosis. Respiration. 2000;67:117–133. doi: 10.1159/000029497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielenski J, Rozmahel R, Bozon D, Kerem B, Grzelczak Z, Riordan JR, Rommens J, Tsui LC. Genomic DNA sequence of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. Genomics. 1991;10:214–228. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]