Abstract

A rare 5-exo-dig SNi′ cyclization with magnesiated and lithiated nitriles affords a cis-fused hydrindane bearing an exocyclic allene. The cyclization of the dilithiated nitrile pits a stereoelectronic preference for a trans-hydrindane against a cyclization through a less strained transition structure to the corresponding cis-hydrindane. Computational modeling suggests that the dilithiated nitrile cyclizes to a cis-hydrindane because the preferred transition structure positions the lithium cation in a cone of electron density that bridges the nitrile-bearing carbon, an alkoxide, and an electron-rich alkyne functionality.

Keywords: SNi′ cyclization, Metalated nitriles, 5-exo-dig, Hydrindane

Metalated nitriles are nucleophilic chameleons that change the precise geometry of the highly nucleophilic,1 formal carbanion in response to the solvent, temperature, substitution, and the metal cation.2 The structures are partitioned into two distinct types, N-and C-metalated nitriles (Figure 1), depending on whether the metal is coordinated to the nitrile nitrogen or the nucleophilic carbon, 1 and 2, respectively.3

Figure 1.

N- and C-Metalated Nitrile Structures

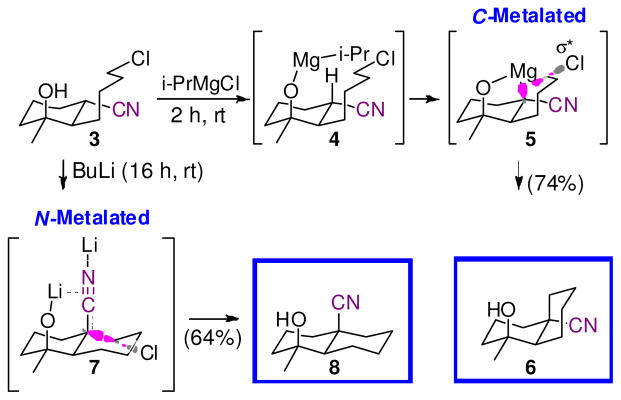

The differing geometries at the nucleophilic carbon can be harnessed to direct cyclizations selectively to cis- and trans-decalins through selective access to N-lithiated and C-magnesiated nitriles (Scheme 1).4 Deprotonating 3 with i-PrMgCl triggers an internally directed deprotonation 4 → 5 and an SNi displacement via the C-magnesiated nitrile 5 to the cis-decalin 6. Employing BuLi to deprotonate 3 affords the N-lithiated nitrile 7 in which the strong lithium-π interaction5 between the electron-rich nitrile π-electrons6 and the adjacent lithium alkoxide anchors the nitrile in an axial orientation for cyclization to the trans-decalin 8.

Scheme 1.

Cation-controlled decalin cyclizations

The tunable geometry of metalated nitriles is ideal for probing subtle stereoelectronic differences in intramolecular cyclizations. The stereodivergent cyclizations of 3 → 6 and 3 → 8 maintain the same sp3 hybridization of the electrophile while harnessing the tunable geometry of the nucleophilic carbon to control the SNi displacement. More subtle is the electrophile hybridization which can profoundly influence the course of SNi and SNi′ displacements.7 As originally formulated, the nucleophilic SNi′ attack angle on an sp hybridized carbon, Nu-C≡C, was postulated to be acute (Scheme 2, 9 → 10), maintaining a trajectory with the propargylic substituent close to the 120° angle in the forming allene (atoms highlighted in purple).

Scheme 2.

SNi′ displacement trajectories.

Calculations,8 and accumulating experimental evidence,9 suggest that SNi′ displacements on propargyllic electrophiles actually involve an obtuse attack angle (Scheme 2, 10′ → 11′). Estimates of the attack angle vary between 115–130° depending on the extent of bond formation in the TS. Simplistically, an obtuse attack avoids the electronic repulsion between the nucleophilic electron pair and the π-electrons of the alkyne that occurs in an acute attack.

SNi′ displacements with propargyllic electrophiles are rare,10 in large part because of the difficulty in generating anionic nucleophiles in the presence of reactive propargylic electrophiles. Metalated nitriles, although not used previously for SNi′ displacements, are ideal because of their facile formation through deprotonation,11 halogen-metal,12 sulfoxide-metal,13 and sulfide-metal14 exchange and because their formation is highly tolerant of delicate functionality. In addition, the tunable nucleophile geometry, through metal counter-ion selection,2 allows control over developing bond angles for stereoselective cyclization.

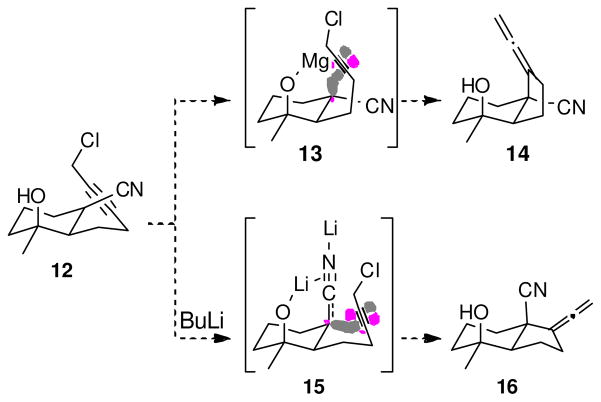

Tuning the stereochemistry of a metalated nitrile in an SNi′ displacement provides a potential solution to the long-standing difficulty in synthesizing hydrindanes.15 trans-hydrindanes are prevalent in natural products, but are more difficult to synthesize than their generally more stable cis-counterparts (Scheme 3, compare 14 and 16).15,16 Conceptually, deprotonating 12 with excess i-PrMgCl should generate the C-magnesiated nitrile 13 that would cyclize to the cis-hydrindane 14. Cyclization of the corresponding lithiated nitrile 15 having complexation between the alkoxy lithium and the nitrile π-electrons, should lead to the trans-hydrindane 16. The cyclization of 15 pits a stereoelectronic preference for an obtuse attack against torsional strain inherent in the structure of a trans-hydrindane. Described in this report is the synthesis of the cyclization precursor 12, the cyclizations of 12 with i-PrMgCl and BuLi, and a computational analysis of the dilithiated nitrile derived from 12.

Scheme 3.

Stereodivergent hydrindanes cyclizations.

Rapid access to the cyclization precursor 12 was predicated on an efficient 1,2-1,4-double addition to oxonitrile 17 (Scheme 4).17 Sequential addition of MeMgCl and 3-butenylmagnesium bromide to oxonitrile 17 18 smoothly provided the substituted cyclohexanecarbonitrile 18. Silyl protection of the tertiary hydroxyl group followed by ozonolysis19 provided aldehyde 19. Exposing 19 to dibromomethylene-triphenylphosphorane triggered dibromo-olefination20 accompanied by extensive cleavage of the silyl ether to afford 20a (50%) and the silyl ether 20b (38%). Brief exposure of 20b to Bu4NF quantitatively afforded 20a. Subsequent treatment of 20a with excess BuLi and interception of the intermediate acetylide with gaseous formaldehyde provided the acetylenic alcohol 21. Having installed the requisite carbon skeleton, alcohol 21 was chlorinated21 to provide the cyclization precursor 12.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the Cyclization Precursor

Exposing hydroxynitrile 12 to excess i-PrMgCl triggers a smooth cyclization to the cis-hydrindane 14 (Scheme 5).22 Forming the cis-hydrindane 14 is consistent with cyclization through a three-centered C-magnesiated nitrile 13 having a side-on overlap in the SE2(Ret) displacement.23

Scheme 5.

SNi′ hydrindane cyclizations.

Cyclizing 12 by deprotonating with BuLi affords the same cis-hydrindane 14 (Scheme 5). The absence of any trans-hydrindane indicates that the internal coordination between the alkoxy lithium and the electron rich nitrile5 is insufficient to achieve the orientation for cyclization through 15. Presumably, the developing torsional strain prevents cyclization through 15 which instead occurs through 15′.24

The preference of the lithiated nitrile 15 to cyclize to a cis-hydrindane stimulated a computational analysis25 to gain insight into the factors controlling the cyclization. The AM1 semi-empirical quantum chemistry method,26 incorporating the PCM continuum solvation model with THF as solvent,27 was used to analyze the structural and activation enthalpy differences between the transition structures. Frequency analysis was used to confirm all stationary points as transition structures28 in the dilithiated models.

Two different cis-transition structures were identified (Figure 2). The two transition structures TS1 and TS2 both contain a centrally located lithium cation that bridges the nitrile-bearing carbon and the alkoxide. In addition, the lithium cation interacts with the electron-rich alkyne functionality and maintains two C–H interactions that creates an ideally oriented cone of electron density for the lithium cation to reside in. TS1 and TS2 differ in the coordination of the second lithium atom; in TS1 lithium coordinates to the alkoxide whereas in TS2 lithium coordinates to the nitrile nitrogen. TS1, formally a C-lithiated nitrile, is computed to be 8.4 kcal/mol higher in energy than TS2 which is both C- and N-lithiated. Coordination of lithium to the nitrile nitrogen in TS2 removes electron density from the nucleophilic carbon which stabilizes the transition structure; the breaking/forming bond of TS2 (2.09 Å) is significantly shorter than that of TS1 (2.15 Å). The lithium cation bridging the alkoxide and the nucleophilic carbon has a shorter Li-O bond in TS2 (2.19 Å) compared with TS1 (2.26 Å) and a longer Li-C interaction with the nucleophilic α-carbon of the nitrile (3.01 Å for TS2 compared with 2.84 Å for TS1).

Figure 2.

TS for SNi′ cyclizations to cis-hydrindanes

Several transition structures analogous to TS1 and TS2 were explored for cyclization to the corresponding trans-hydrindane. Despite extensive optimization, only one transition structure was located that would afford a trans-hydrindane (TS3, Figure 3). In TS3 one lithium cation bridges the alkoxide and the nitrile nitrogen while the other associates with the alkoxide. The computed energy of TS3 is 1.9 kcal/mol and 6.4 kcal/mol higher in energy than TS1 and TS2, respectively. Of the three computationally identified transition structures, the lowest energy transition structure TS2 is stabilized by lithium encapsulation through a series of interactions with electron rich contacts that serve to guide the cyclization to the cis-hydrindane 14. The computational identification of transition structure TS2 as the low energy structure reveals a dual C- and N-lithiation not captured in the simplistic representation 15′.

Figure 3.

TS for SNi′ cyclization to a trans-hydrindane.

The cyclizations of 12 are the first SNi′ displacements of a propargylic electrophile by metalated nitriles. Formation of the C-magnesiated nitrile sets the stereochemistry of the nucleophilic C-Mg bond which directs cyclization to the cis-hydrindane 14. Cyclization via the corresponding lithiated nitrile pits internal complexation between lithium and the nitrile π-electrons in the developing trans-hydrindane against cyclization to a more flexible cis-hydrindane. Computational modeling indicates that the cis-hydrindane 14 is favored because of an unusual encapsulation of one lithium cation through coordination to a series of electron rich contact points accompanied by a favorable coordination of the second lithium to the nitrile nitrogen. Collectively, the cyclizations are the first SNi′ displacements of metalated nitriles with propargylic electrophiles, a test of lithium-nitrile π-coordination in cyclizations of small rings, and identify an unusual encapsulation of lithium in an SNi′ displacement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (2R15AI051352-03) and in part from the National Science Foundation (IRD and CHE-1126465) are gratefully acknowledged. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF or NIH.

Footnotes

Supplementary data (experimental procedures, characterization data, proton and carbon spectra of all compounds and computational information) associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Bug T, Mayr H. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12980. doi: 10.1021/ja036838e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Fleming FF, Shook BC. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Shook BC. J Org Chem. 2002;67:2885. doi: 10.1021/jo016156e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming FF, Wei Y, Liu W, Zhang Z. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7477. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.05.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Fleming FF, Gudipati S. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:5365. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200800715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Zhang Z. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:747. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Sasaki M, Shirakawa Y, Kawahata M, Yamaguchi K, Takeda K. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:3363. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Vu VA, Shook BC, Raman M, Steward OW. J Org Chem. 2007;72:1431. doi: 10.1021/jo062270r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davis FA, Mohanty PK. J Org Chem. 2002;67:1290. doi: 10.1021/jo010988v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Davis FA, Mohanty PK, Burns DM, Andemichael YW. Org Lett. 2000;2:3901. doi: 10.1021/ol006654u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Schrader T, Kirsten C, Herm M. Phosphorous, Sulfur, Silicon. 1999;144–146:161. [Google Scholar]; (f) Gmeiner P, Hummel E, Haubmann C. Liebigs Ann. 1995:1987. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19953280311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Murray AW, Murray ND, Reid RG. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1986:1230. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metalated nitriles are more electron rich than their neutral parent nitriles: Wu F, Foley SR, Burns CT, Jordan RF. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1841. doi: 10.1021/ja044122t.Groux LF, Weiss T, Reddy DN, Chase PA, Piers WE, Ziegler T, Parvez M, Benet-Buchholz J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1854. doi: 10.1021/ja044119+.

- 7.Baldwin JE. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1976:734. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Strozier RW, Caramella P, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:1340. [Google Scholar]; (b) Houk KN, Strozier RW, Rozeboom MD, Nagaze S. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:323. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Gilmore K, Alabugin IV. Chem Rev. 2011;111:6513. doi: 10.1021/cr200164y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alabugin IV, Manoharan M, Zeidan TA. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14014. doi: 10.1021/ja037304g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Alabugin IV, Zeidan TA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3175. doi: 10.1021/ja012633z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devambatla RKV, Velagaleti R, Yarravarapu N, Fleming FF. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:2925. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watt DS, Arseniyadis S, Kyler KS. Org React. 1984;31:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Pitta BR, Fleming FF. Org Lett. 2010;12:2810. doi: 10.1021/ol100897y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Zhang Z, Liu W, Knochel P. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2200. doi: 10.1021/jo047877r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fleming FF, Zhang Z, Knochel P. Org Lett. 2004;6:501. doi: 10.1021/ol036202s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nath D, Fleming FF. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:11790. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nath D, Skilbeck M, Coldham I, Fleming FF. Org Lett. 2014;16:62. doi: 10.1021/ol403020s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming FF, Vu VA, Shook BC, Raman M, Steward OW. J Org Chem. 2007;72:1431. doi: 10.1021/jo062270r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankowski P, Marczak S, Wicha J. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:12071. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Fleming FF, Wei G, Zhang Z, Steward OW. J Org Chem. 2007;72:5270. doi: 10.1021/jo070678y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Steward OW. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:1126. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Lujan-Montelongo JA, Fleming FF, Hughes D. Org Synth. 2013;90:229. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming FF, Zhang Z, Wei G. Synthesis. 2005:3179. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Temporary protection of the alcohol was required to circumvent attack on the intermediate ozonide and dehydration to the corresponding pyran.

- 20.Corey EJ, Fuchs PL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972:3769. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appel R. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1975;14:801. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The 13C chemical shift of the nitrile carbon provides a reliable, and diagnostic means of assigning stereochemistry: Fleming FF, Wei G. J Org Chem. 2009;74:3551. doi: 10.1021/jo900286f.

- 23.Gawley RE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4297. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Equilibration between C- and N-lithiated nitriles has been detected by NMR: Sott R, Granander J, Hilmersson G. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6798. doi: 10.1021/ja0388461.

- 25.The Gaussian 09 quantum chemistry packagea was used with the computational resources at the Center for Computational Sciences.bFrisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam MJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2009. (b) Center for Computational Sciences at Duquesne University Supported by National Science Foundation: CHE-0723109 and CHE-1126465 and United States Department of Education: P116Z080180 and P116Z050331.

- 26.Thiel Walter. Semiempirical quantum–chemical methods. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science. 2014 Mar-Apr;4(2):145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Morao I, McNamara JP, Hillier IH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:628. doi: 10.1021/ja027326n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Iron MA, Martin JML, van der Boom ME. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11702. doi: 10.1021/ja036723a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Freccero M, Di Valentin C, Sarzi-Amade M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3544. doi: 10.1021/ja028732+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acevedo O, Evanseck JD. Transition States and Transition Structures. In: Bultinck P, De Winter H, Langenaeker W, Tollenaere JP, Dekker M, editors. Computational Medicinal Chemistry for Drug DiscoVery. Marcel and Dekker; New York: 2004. p. 323. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.