Abstract

Background

29 autoimmune diseases, including Rheumatoid Arthritis, gout, Crohn’s Disease, and Systematic Lupus Erythematosus affect 7.6-9.4% of the population. While effective therapy is available, many patients do not follow treatment or use medications as directed. Digital health and Web 2.0 interventions have demonstrated much promise in increasing medication and treatment adherence, but to date many Internet tools have proven disappointing. In fact, most digital interventions continue to suffer from high attrition in patient populations, are burdensome for healthcare professionals, and have relatively short life spans.

Objective

Digital health tools have traditionally centered on the transformation of existing interventions (such as diaries, trackers, stage-based or cognitive behavioral therapy programs, coupons, or symptom checklists) to electronic format. Advanced digital interventions have also incorporated attributes of Web 2.0 such as social networking, text messaging, and the use of video. Despite these efforts, there has not been little measurable impact in non-adherence for illnesses that require medical interventions, and research must look to other strategies or development methodologies. As a first step in investigating the feasibility of developing such a tool, the objective of the current study is to systematically rate factors of non-adherence that have been reported in past research studies.

Methods

Grounded Theory, recognized as a rigorous method that facilitates the emergence of new themes through systematic analysis, data collection and coding, was used to analyze quantitative, qualitative and mixed method studies addressing the following autoimmune diseases: Rheumatoid Arthritis, gout, Crohn’s Disease, Systematic Lupus Erythematosus, and inflammatory bowel disease. Studies were only included if they contained primary data addressing the relationship with non-adherence.

Results

Out of the 27 studies, four non-modifiable and 11 modifiable risk factors were discovered. Over one third of articles identified the following risk factors as common contributors to medication non-adherence (percent of studies reporting): patients not understanding treatment (44%), side effects (41%), age (37%), dose regimen (33%), and perceived medication ineffectiveness (33%). An unanticipated finding that emerged was the need for risk stratification tools (81%) with patient-centric approaches (67%).

Conclusions

This study systematically identifies and categorizes medication non-adherence risk factors in select autoimmune diseases. Findings indicate that patients understanding of their disease and the role of medication are paramount. An unexpected finding was that the majority of research articles called for the creation of tailored, patient-centric interventions that dispel personal misconceptions about disease, pharmacotherapy, and how the body responds to treatment. To our knowledge, these interventions do not yet exist in digital format. Rather than adopting a systems level approach, digital health programs should focus on cohorts with heterogeneous needs, and develop tailored interventions based on individual non-adherence patterns.

Background

Digital Health Interventions

In the mid-1980’s research began to examine how digital technology could be facilitate improved patient health [1,2]. Since then, evidence has indicated that many patients would prefer to communicate with their physician via email [3], that patient-led Internet support systems can safely help with complex behavioral issues [4], and that physicians, payers and hospital systems could benefit by leveraging the Internet to improve communication amongst stakeholders [5]. Several Cochrane reviews have indicated that digital health programs can be a benefit to patients [6–10], however to our knowledge, the literature has not identified effective digital programs for autoimmune disorders.

Digital health tools have traditionally centered on the transformation of existing paper-based interventions (such as diaries, trackers, stage-based or cognitive behavioral therapy programs, web-based coupon downloads, or symptom checklists) to electronic format. Advanced digital interventions have also incorporated attributes of Web 2.0 such as social networking, text messaging, and the use of video. However, Internet interventions typically have high attrition and have so far failed to produce population effects [11–13].

To further complicate matters, failures to deliver effective systems, tools and interventions have been reported in countries traditionally associated with high Internet adoption rates. Countries such as Australia [14,15], Canada [16,17], the United Kingdom [18,19] and the United States [20–22] have all reported massive eHealth failures, and the potential of digital health remains unrecognized.

The Adherence Problem

A well-known, systemic problem in healthcare is medication non-adherence. The World Health Organization estimates that the average non-adherence rate in developed countries is 50% among patients with chronic conditions [23]. Other studies estimate that non-adherence in North American accounts for $300 billion dollars in avoidable costs, annually [24–26].

Non-adherence is a complex problem. At the patient level, medication non-adherence is generally defined as intentional or non-intentional [27]. Strongly associated with personal beliefs and perceptions, patients actively choose to ignore treatment in intentional non-adherence, whereas unintentional non-adherence involves a passive process [28,29]. Risk factors in treatment are well reported in the literature [30–32] and are generally labeled as modifiable (behavior-based) or non-modifiable (eg. age, gender).

Identifying a patient’s unique non-adherence patterns is time consuming, and existing paper-based processes that require scoring, are complex and often expensive to administer.

Digital Health Interventions and Non-Adherence

One of the most attractive aspects of digital health is the ability to use algorithms to tailor interventions to individual preferences [33–35]. However, and as mentioned previously, most interventions are based on traditional approaches designed for large homogenous populations.

Rather than adopting a systems-level approach, digital health might focus on cohorts with heterogeneous needs, and develop tailored interventions based to individual non-adherence patterns.

To our knowledge, publicly-available digital health tools designed to target specific non-adherence behaviors in autoimmune diseases do not exist. As a first step in investigating the feasibility of developing such a tool, the objective of the current study is to systematically rate factors of non-adherence that have been reported in past research studies.

Although several risk factors are well known (cost, forgetfulness, co-morbidities), they have yet to be grouped, ranked or systematically categorized. To uncover common risk factors observed by researchers, we systematically reviewed qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods literature that reported factors noted in their respective cohorts.

Recognized as a rigorous method to facilitate the emergence of common themes in previously published literature, we used Grounded Theory (GT) as process to uncover these factors [36]. Before describing the specific GT methodology used in our research, an outline of the magnitude of non-adherence among autoimmunology stakeholders will be first presented.

The Adherence Problem

Approximately 8–9% of the population is affected by 29 autoimmune diseases, including Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), gout, Crohn’s Disease (CD), and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) [37]. As is typical with chronic conditions, many patients do not adhere to long-term therapies. In autoimmunology, reported estimates of non-adherence in research studies range from 7–84% [38–40]. This wide range can be attributed to difficulties in both recording individual rates of non-adherence, and a lack of measurement standards.

Traditional research methods used to measure medication adherence include patient self-report, Electronic Monitoring (EM), and direct observation. Although EM is most accurate, patient self-report and EM may be unreliable as they are potentially subject to the Hawthorne effect [41] (i.e., adherence behavior changes as a result of being monitored, and some researchers choose to not inform patients of monitoring to avoid the observation effect).

In retrospective database studies, adherence is most commonly reported in terms of Medication Possession Ratios (MPR) and/or Proportion of Days Covered (PDC). Deriving MPR and PDC requires access to patient-level treatment utilization data, which is typically retrospective. MPR and PDC are not necessarily accurate, as it cannot be guaranteed that patients are following treatment simply because they are fulfilling prescriptions or collecting medication at expected intervals [42].

The only current means to ensure adherence is by direct observation without patient knowledge [43,44]. Unfortunately, this method is difficult to replicate and perform on a large scare, so true non-adherence rates may be impossible to estimate.

Costs Related to Non-Adherence

As in other chronic conditions, non-adherence rates in autoimmunology lead to increased costs throughout healthcare systems. Costs resulting from the progression of disease and the subsequent need for more aggressive treatment also result in significant economic burden [45], and when immunological diseases are comorbid with other conditions, non-adherence to proven treatment increased health risks and costs for both disorders [46].

Likewise, adherent patients contribute to positive health benefits and economic outcomes. For example, a cohort study of 834 SLE patients found that decreased adherence led to increased visits to rheumatologists, primary care physicians, other care provides, emergency departments, and hospitalizations [47]. While adherence resulted in shorter hospital length of stay and lower inpatient costs in CD patients in one study [48], another discovered that when compared to adherent ulcerative colitis patients, those who were non-adherent incurred twice the inpatient costs and significantly greater overall health care costs [49].

Methods

Rigorously reviewing literature with Grounded Theory

Founded by Glaser and Strauss in 1967, GT is an objectivist methodology used to develop theoretical interpretations without defining phenomenon a priori [50]. In conducting GT, researchers first familiarize themselves with prior research to determine a general research question, followed by a mechanistic review and classification of data [51]. As it is a research method involving discovery through systematic analysis, data collection and coding [52], past studies have recognized GT as a method to study social psychological themes across diverse chronic illnesses [53].

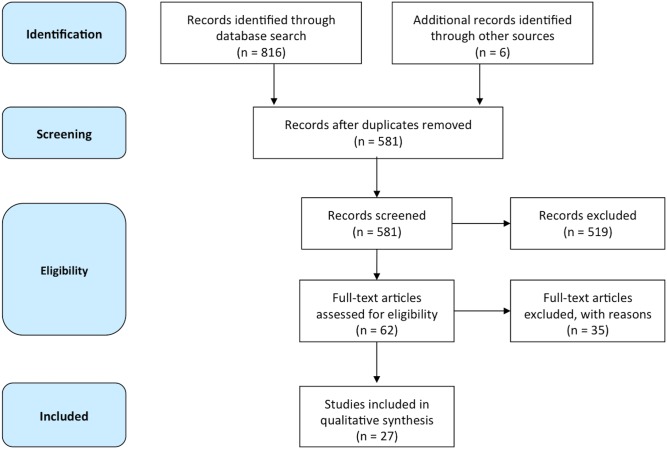

To uncover themes in previously published research, this study utilized the five-stage process outlined by Wolfswinkel et al. to conduct a rigorous literature review (Define, Search, Select, Analyze, Present) [36]. When followed correctly, this process assures an in-depth analysis of empirical facts, interrelationships and dependencies beyond a particular area, and the emergence of themes. In addition, this review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist for systematic reviews [54]. The PRISMA flow diagram is provided in Fig 1. The PRISMA checklist is provided in S1 PRISMA Checklist.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Database and search methodology (Define, Search)

In the Define stage, we conducted a general literature review of various issues related to medication non-adherence over a number of chronic disease conditions. Initial findings primarily centered on recurring problems related to lack of defined terminologies (adherence, compliance, persistence, concordance) [55,56], delivery mechanisms (oral, subcutaneous, infusion), dose measurement [42], the doctor-patient relationship [57], and the ineffective nature of existing interventions [58,59].

During the Search stage, the databases PubMed and Google Scholar were searched in May 2013. PubMed was selected as it is a standardized database frequently referenced by physicians to seek information, and Google Scholar was utilized as it has recently been identified as an accurate reference for quick clinical searches [60].

As mentioned previously, there are 29 autoimmune diseases, and the literature on all of these disorders is vast. Likewise, the research on non-adherence and related terminology (e.g. compliance, concordance, discordance, persistence, shared decision-making, the therapeutic alliance), delivery mechanisms and does regimen is also voluminous. In order to gain insight on the research question and to simplify the search process, we limited MeSH keywords to a subset of autoimmune disorders.

The keywords rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatology, gout, crohn’s disease, systematic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease and medication adherence were used in the search process. The initial database search returned 816 records. Following the removal of duplicates, 581 abstracts were included for further analysis.

Study selection (Select)

For the purpose of knowledge generation, meta-analyses, Cochrane reviews, case studies, reports, letters to the editor and opinion articles were reviewed in the initial screening process, but to synthesize results and remove the possibility of replication, were excluded in the coding process.

Fig 1 presents the PRISMA flow chart for the selection of included studies. Articles were included for eligibility coding if they met the following criteria:

Peer-reviewed studies reporting primary data only.

Quantitative (e.g. as measured by MPR or PDC), qualitative (e.g. through the use of surveys or interviews), and mixed-methods studies that measured adherence within autoimmunology indications.

Articles in English language only

Any jurisdiction or geographical location.

Study selection was conducted in two stages—initial screening (TvM) and subsequent validation by a second researcher (RF). The first researcher screened the 581 abstracts, confirming 519 did not meet study criteria, resulting in 62 potentially relevant studies. The Select process then required a full examination of the 62 articles. Following full examination, a further 34 articles were discarded, leaving 28 studies that met all inclusion criteria. Double-checking this process with the second researcher resulted in the further exclusion of one additional study, leaving 27 studies.

Coding of studies (Analyze)

As recommended by Wolfswinkel et al, open, axial and selective coding was applied systematically to all included studies. In open coding, researchers reviewed the 27 studies to develop and categorize meta-insights and concepts. Following this, all studies were re-reviewed and re-coded to investigate the consistency of meta-insights and themes (axial coding), resulting in the establishment of main themes and patterns. Finally, researchers performed selective coding where theoretical saturation of themes and patterns was established. As outlined in GT study protocol, a reliability check was conducted to confirm risk factor identification, coding procedure, scoring, and results [61]. Each study was coded with NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 10.

Risk factors were only coded if they were explicitly noted in the Results, Discussion or the Conclusion section of each study. If a risk factor was identified in a study it received a score of one. Even if the risk factor was noted numerous times in each study, the maximum score a risk factor could receive in a single study was one (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Studies Reporting Factors of Non-Adherence (n = 27).

| Citation | Research Method/Sample | Country of Origin | Disease | Non-Adherence Factor(s) Listed / Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bermejo et al., 2010 | Survey (N = 107) | Spain | Inflammatory bowel disease | Patient does not understand treatment, Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Dose regimen Lack of motivation or social support, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Cannon et al., 2011 | Retrospective database (N = 1412) | USA | Rheumatoid arthritis | Ethnicity, Gender (females less adherent), Disease severity, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| Dalbeth et al., 2012 | Cross sectional assessment (N = 273) | New Zealand | Gout | Ethnicity, Gender (males less adherent), Patient does not understand treatment, Lack of motivation or social support, Disease severity, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| de Turrah et al., 2010 | Longitudinal study (N = 941) | Denmark | Rheumatoid arthritis | Disease duration, Perceived medication ineffectiveness, Disease severity, Comorbid conditions, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| de Turrah et al., 2010 | Retrospective database, questionnaire (N = 126) | Denmark | Rheumatoid arthritis | Disease duration, Patient does not understand treatment, Perceived medication ineffectiveness, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| Daleboudt et al., 2011 | Questionnaire (N = 106) | New Zealand | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Age, Ethnicity, Patient does not understand treatment, Side effects Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Mood disorder, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Garcia-Gonzalez et al., 2008 | Cross-sectional survey (N = 102) | USA | Rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus | Ethnicity, Side-effects, Perceived medication ineffectiveness, Patient-centric approach |

| Harrold et al., 2010 | Interview (N = 26) | USA | Gout | Side-effects, Perceived medication ineffectiveness, Lack of motivation or social support, Cost, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Harrold et al., 2009 | Retrospective database (N = 4166) | USA | Gout | Age (older more adherent), Comorbid conditions, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Hetland et al., 2012 | Retrospective database, questionnaire (N = 2326) | Denmark | Rheumatoid arthritis | Age (younger more adherent), Side effects, Perceived medication ineffectiveness |

| Horne et al., 2009 | Cross sectional survey (N = 1871) | USA | Inflammatory bowel disease | Age (older more adherent), Disease duration, Patient does not understand treatment, Side-effects, Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Dose regimen, Perceived mediation ineffectiveness Disease severity, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Hughes et al., 2011 | Feasibility survey (N = 112) | United Kingdom | Rheumatoid arthritis | Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| Julian et al., 2009 | Retrospective database, Telephone survey (N = 834) | USA | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Disease duration, Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Dose regimen, Mood disorder, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Koneru et al., 2008 | Retrospective database, questionnaire (N = 63) | USA | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Ethnicity, Patient does not understand treatment, Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Dose regimen, Forgetting instructions, Mood disorder, Lack of motivation or social support, Comorbid conditions, Cost, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Kamperidis et al., 2012 | Retrospective database (N = 238) | United Kingdom | Inflammatory bowel disease | Age (younger less adherent), Comorbid conditions, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| Lakotos et al., 2010 | Questionnaire (N = 655) | Hungary | Inflammatory bowel disease | Side effects, Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Dose regimen, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Li et al., 2010 | Retrospective database | USA | Rheumatoid arthritis | Ethnicity, Side effects, Dose regimen |

| Lorish et al., 1990 | Interview (N = 140) | United Kingdom | Rheumatoid arthritis | Patient does not understand treatment, Side effects, Forgetfulness or inconvenience, Dose regimen, Perceived mediation ineffectiveness, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Marengo et al., 2012 | Questionnaire, laboratory testing, electronic monitoring (N = 78) | USA | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Patient does not understand treatment, Dose regimen, Mood disorder, Comorbid conditions, Risk stratification tool or intervention, recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Muller et al., 2012 | Questionnaire (N = 1199) | Estonia | Rheumatoid arthritis | Age (younger less adherent), Patient does not understand treatment, Side effects, Forgetting instructions, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Moshkovska et al., 2009 | Questionnaire, laboratory testing (N = 169) | United Kingdom | Ulcerative colitis | Age (younger less adherent), Ethnicity Side effects, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Nahon et al., 2012 | Questionnaire (N = 1663) | France | Inflammatory bowel disease | Mood disorder, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| Nguyen et al., 2009 | Retrospective database, Cross sectional (N = 235) | USA | Inflammatory bowel disease | Age (younger less adherent), Ethnicity, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Pascual-Ramos et al., 2009 | Retrospective database, interview (N = 75) | Mexico | Rheumatoid arthritis | Age (older less adherent), Forgetting instructions, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Richards et al., 2012 | Retrospective database (N = 1372) | USA | Rheumatoid arthritis | Ethnicity, Dose regimen, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended |

| Tuncay et al., 2007 | Questionnaire (N = 100) | Turkey | Rheumatoid arthritis | Age (younger less adherent), Disease severity, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

| Zwikker et al., 2012 | A multidisciplinary tasks group | The Netherlands | Rheumatoid arthritis | Patient does not understand treatment, Side effects, Lack of motivation or social support, Risk stratification tool or intervention recommended, Patient-centric approach recommended |

Analysis strategy (Present)

Following the reliability check, coding was synthesized to formulate a holistic set of findings and insights that are specific to understanding why, despite proven efficacy of treatment, autoimmunology patients are typically non-adherent.

Results

The characteristics of studies varied and included retrospective database analyses, patient surveys, cross-sectional assessments, longitudinal studies, questionnaires, patient interviews, feasibility surveys, telephone surveys, laboratory tests, multidisciplinary task groups and electronic monitoring. Type of study also varied, with six quantitative, 12 qualitative and nine mixed-method studies (Tables 2 and 3). This variation contributed to the aim of this study as strong common themes emerged across vastly different study designs.

Table 2. Non-modifiable Risk Factors.

| Total Number of Studies | Age | Ethnicity | Disease Duration | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies (n) % | 6 | (2) 33% | (2) 33% | (2) 33% | (0) 0% |

| Qualitative Studies (n) % | 12 | (4) 33% | (3) 23% | (1) 8% | (1) 8% |

| Mixed Studies (n) % | 9 | (4) 44% | (4) 44% | (2) 22% | (1) 11% |

| Total (n) % | 27 | (10) 37% | (9) 33% | (5) 19% | (2) 7% |

Table 3. Modifiable Risk Factors.

| Total Studies | Patient does not understand treatment | Side effects | Dose regimen | Perceived medication ineffectiveness | Forgetfulness or inconvenience | Disease severity | Comorbid condition | Presence of mood disorder | Lack of motivation or social support | Forgetting instructions | Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies (n) % | 6 | (2) 33% | (1) 17% | (3) 50% | (1) 17% | (0) 0% | (1) 17% | (4) 67% | (1) 17% | (0) 0% | (0) 0% | (0) 0% |

| Qualitative Studies (n) % | 12 | (6) 50% | (8) 67% | (3) 25% | (4) 33% | (6) 50% | (3) 25% | (0) 0% | (2) 17% | (3) 25% | (1) 8% | (1) 8% |

| Mixed Method Studies (n) % | 9 | (4) 44% | (2) 22% | (3) 33% | (4) 44% | (2) 22% | (2) 22% | (2) 22% | (3) 33% | (1) 11% | (2) 22% | (1) 11% |

| Total (n) % | 27 | (12) 44% | (11) 41% | (9) 33% | (9) 33% | (8) 30% | (6) 22% | (6) 22% | (6) 22% | (4) 15% | (3) 11% | (2) 7% |

Studies were published between 1990 and 2012. Twelve studies were based on study populations within North America (11 USA, one Mexico), 13 studies were based on Western/Eastern Europe and Middle East populations (10 Western Europe, two Eastern Europe and one Middle East), and two studies were based on AustralAsia populations (two New Zealand). Twelve studies focused on RA patients, six in IBD, five in SLE, three in Gout, and one in UC.

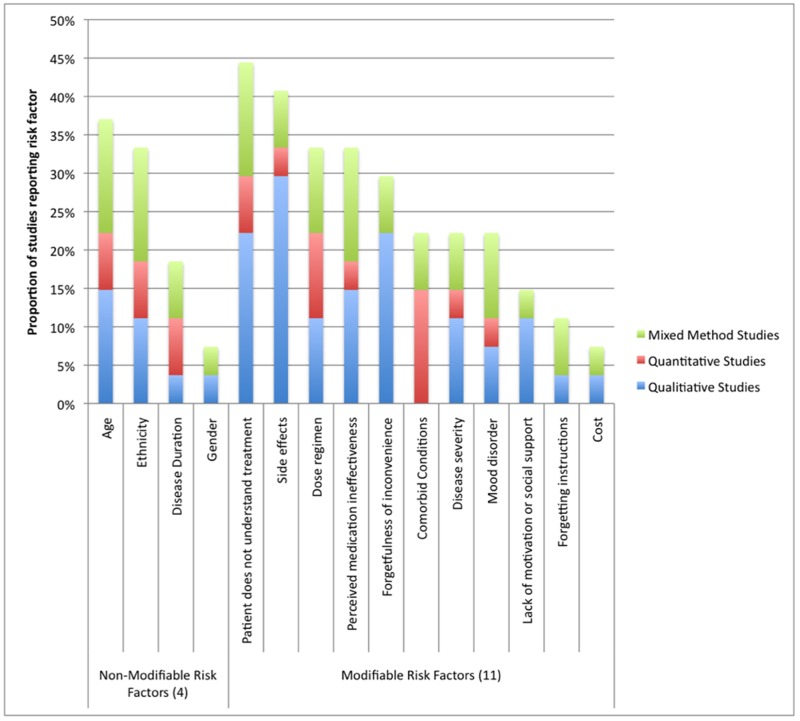

Out of the 27 studies, four non-modifiable and 11 modifiable risk factors were uncovered (Fig 2. and Tables 2 and 3). The four non-modifiable risk factors were age, race/ethnicity, gender, and disease duration. The 11 modifiable risk factors included patients not understanding treatment, side effects / adverse events, forgetfulness / inconvenience, dose regimen, forgetting instructions, medication ineffectiveness, presence of a mood disorder, lack of motivation or social support, disease severity, cost, and presence of a comorbid condition.

Fig 2. Proportion of studies reporting modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.

Across all study types and indications, the most commonly described determinants of medication non-adherence, confirmed in ≥33% of studies, were patients not understanding treatment (44%), side effects (41%), age (37%), dose regimen (33%), forgetfulness/inconvenience (33%), perceived medication ineffectiveness (33%) and ethnicity (33%).

Specifically looking at the 37% of studies reporting age as a non-modifiable factor, 30% indicated that adherence increased as age progressed, while 7% indicated that younger people were more adherent (Table 4).

Table 4. Sub-set of age.

| Total Number of Studies (N) | Age | Younger age more adherent | Older age more adherent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Quantitative Studies (n) % | 6 | (2) 33% | (0) 0% | 2 (33%) |

| Number of Qualitative Studies (n) % | 12 | (4) 33% | (0) 0% | 4 (31%) |

| Number of Mixed Studies (n) % | 9 | (4) 44% | 2 (22%) | 2 (22%) |

| Total (n) % | 27 | (10) 37% | 2 (7%) | 8 (30%) |

Limiting studies to US-based populations only (n = 11), the most common modifiable factors (reported in ≥33% of studies) were dose regimen (55%), and patients not understanding treatment (45%), with side effects and perceived medication ineffectiveness at 36%. Ethnicity (55%) was the most common non-modifiable factor.

The most common factors (reported in ≥50% of studies) in RA specific studies conducted in the USA (n = 4) were dose regimen (75%), ethnicity (50%), patients not understanding treatment (50%) and co-morbid conditions (50%).

An unexpected finding was that the vast majority of study authors overwhelmingly advocated for the development of risk stratification tools (81% of reported studies) with a patient-centric approach (67% of reported studies) (Table 5).

Table 5. Recommended Treatment Approaches.

| Total Number of Studies (N) | Articles advocating for the need for a risk stratification tool or intervention | Articles advocating for a patient-centric approach to treatment for non-adherence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies (n) % | 6 | (5) 83% | (2) 33% |

| Qualitative Studies (n) % | 12 | (10) 83% | (10) 83% |

| Mixed Studies (n) % | 9 | (7) 78% | (6) 67% |

| Total (n) % | 27 | (22) 81% | (18) 67% |

Despite variations in study characteristics, year, location and differing target groups, recommendations for risk-stratification tools and a patient-centric approach appeared in the majority of studies.

Discussion

As we uncover the factors leading to non-adherence, we can begin to build profiles and digitally tailor content. Past research has shown that clinical characteristics can be used to maximize website utilization, and that short, tailored exercises may attract a wider audience [62]. However, this has not been attempted in autoimmunology.

Three of the five modifiable risk factors (not understanding treatment, perceived medication ineffectiveness and forgetfulness/inconvenience) could be addressed through targeted patient communications, shared decision making tools, or more regular patient interaction [63]. The relationship between side effects and non-adherence is longstanding across many therapeutic areas [64–70], and might be a central focus of program content (e.g. support group discussions or text messages).

Forgetfulness and inconvenience were frequently cited in the literature (33% of studies). While text messaging and email reminders could manage general forgetfulness, auto-immune diseases are serious and often painful, so it is most likely important to consider behavioral motivations behind non-adherence. Immunological disorders and medicine are understandably inconvenient, however as noted by the WHO [23], the long-term consequences of non-adherence compromise patient safety and quality of life. Digital tools should be not be paternalistic, and allow patients to make cost-benefit decisions in collaboration with their physicians.

Five studies found that non-adherence increased as the frequency of dosing increased [44,71–74], two studies indicated that non-adherence increased as regimens became more complex [47,75], and one found a negative relationship between adherence and duration of therapy [76]. In 2010, Li et al found that infusion patients were more adherent than those on injection schedules, and also attributed increased adherence to decreased frequency of administration and clinical assistance from physicians or nurses [45]. From these results it is clear that digital interventions need to be tailored to medication dose frequency.

In the past, significant effort to address non-adherence has been placed on reducing costs to patients and providing patients with detailed instructions on drug application. However, our findings indicate that cost (7%) and forgetting instructions (11%) were less impactful than other modifiable factors. The impact of cost on an individual or families’ decision to pursue treatment is difficult to measure, especially in the complex US market where there is a paucity of empirical evidence explaining how demand and supply prices influence utilization [77]. Interventions that focus on how and when to administer medication have also proven to be ineffective [78]. Based on our results, the impact of efforts spent at circumventing cost (downloadable coupons, assistance programs) and providing instructions (printouts, detail aids) should be reassessed, or be considered as part of a holistic framework of activities designed to address the issue of non-adherence.

Given the tremendous health and economic costs attributed to medication non-adherence in autoimmune diseases, the vast majority of publications (81%) identified the need for risk stratification tools or interventions that are patient–centric (67%). Risk stratification tools exist today, but they are largely physician-focused and have yet to be digitized. Some examples typically used in autoimmunology are the Compliance Questionnaire Rheumatology [79], the Medication Adherence Rating Scale [80], the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale [81] and the Rheumatoid Arthritis Severity Scale [82]. As in other condition areas, these standardized tools and assessments can be modified to provide targeted feedback for both patients and providers [59,78,83–85].

However, careful consideration of process and design must be considered when developing patient-centric interventions. Past attempts in autoimmunology showed that physician awareness alone was necessary but not sufficient to improve adherence [86], and interventions may have no impact on patient adherence or quality of life [58].

Limitations and Future Considerations

Limitations are similar to other research employing a GT approach. Only non-adherence risk factors reported in the literature were included and categorized; risk factors not listed within the works may very well exist and outweigh the factors outlined in this study. Regardless, these study results summarize the risk factors supported by the current evidence base and can be easily articulated to experts in non-medical occupations such as website designers, project managers marketers.

Another possible limitation is the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative studies; modifiable risk factors such as forgetfulness or lack of motivation or social support cannot be measured quantitatively. However, despite this limitation it is important to note that forgetfulness or inconvenience was a top modifiable risk factor, and its overall impact is most likely underrepresented.

A significant strength of this study can be found in the GT approach. The study began with no pre-conceived biases, and findings are reflective of determinants of non-adherence deemed important by experts in the field and are evidence based. The relative consistency of top non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors is noteworthy. This study is replicable, and future studies could be undertaken to measure consistency of findings.

Finally, the intention of this research was not to provide conclusive evidence that identifies all determinants of non-adherence for autoimmune diseases. Rather, it is a first step in recognizing common risk factors that can be applied to digital tool development.

Conclusions

According to these findings, adherence outcomes and digital attrition in autoimmunology patients could be improved if patients were given tailored tools to help them gain greater understanding of their disease, the role of medications, and information on side effects, and the role of dose regimen.

Results also indicate that rather than adopting a traditional systems level approach, digital health might focus on cohorts with heterogeneous needs, and develop tailored interventions based on individual non-adherence patterns.

Digital health programs focusing on daily diaries, stage-based modules, standardized reminders and emails have only proven to be moderately successful. A patient’s relationship to treatment is highly personal, and digital interventions should take advantage of technologies that enable tailoring for the unique needs of individuals. Digital health programs addressing other conditions have shown promise, and our evidence indicates that autoimmune patient cohorts may benefit from tailored and accessible electronic resources.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Doug Hyatt, Dr. Fred Ashbury, Dr. Rafael Gomez, and students in the doctoral stream at Henley Business School, University of Reading for comments on the study design. Authors would also like to thank Dr. John Bridges, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health for his comments on the draft manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information Files.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs. Author Michael Ingham is employed by Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC. Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC provided support in the form of salary for author MI, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific role of this author is articulated in the author contributions section. Authors Trevor van Mierlo and Rachel Fournier are employed by Evolution Health Systems Inc. Evolution Health Systems Inc. provided support in the form of salaries for authors TvM and RF, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the author contributions section.

References

- 1. Robinson TN, Walters PA Jr (1986) Health-net: an interactive computer network for campus health promotion. J Am Coll Health 34: 284–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schneider S, Walter R, O'Donnell R (1990) Computerized Communication as a Medium for Behavioral Smoking Cessation Treatment: Controlled Evaluation. Computers in Human Behavior 6: 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Connor A, Edwards A (2001) The role of decision aids in promoting evidence-based patient choice. New York: Oxford Univeristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Selby P, van Mierlo T, Voci SC, Parent D, Cunningham JA (2010) Online social and professional support for smokers trying to quit: an exploration of first time posts from 2562 members. J Med Internet Res 12: e34 10.2196/jmir.1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stone J (2007) Communication between physicians and patients in the era of E-medicine. N Engl J Med 356: 2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Civljak M, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Sheikh A, Car J (2013) Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD007078 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher E, Law E, Palermo TM, Eccleston C (2015) Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD011118 10.1002/14651858.CD011118.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McLean S, Chandler D, Nurmatov U, Liu J, Pagliari C, et al. (2010) Telehealthcare for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD007717 10.1002/14651858.CD007717.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Bailey K, Hayden JA, Stewart SH (2015) Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD011565 10.1002/14651858.CD011565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pal K, Eastwood SV, Michie S, Farmer AJ, Barnard ML, et al. (2013) Computer-based diabetes self-management interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD008776 10.1002/14651858.CD008776.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gill S, Contreras O, Munoz RF, Leykin Y (2014) Participant retention in an automated online monthly depression rescreening program: patterns and predictors. Internet Interv 1: 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eysenbach G (2005) The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res 7: e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fox S (2010) Mobile Health 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. [Google Scholar]

- 14.news.com.au (2013) $1 billion e-health system rejected by doctors as 'shambolic'. newscomau.

- 15. Dutton P (2013) Federal Government to review electronic health records. In: Sport MoHa, editor: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skinner BJ (2009) eHealth Ontario: a case study in the "fatal conceit" of central planning. The Fraser Institute.

- 17.News C (2009) Ehealth scaldal a $1B waste: auditor. CBC News.

- 18.Triggle N (2013) The NHS's troubled relationship with technology. BBC Health News.

- 19.Syal R (2013) Abandoned NHS IT systems has cost $10bn so far. The Guardian.

- 20.Dorfman J (2014) The Failed Oregon Obamacare Website Is Just The Tip Of A $6 Billion Iceberg. Forbes.

- 21.Nicks D (2014) Obamacare Website Was Hacked in July. Time.

- 22.Smith M, Cohen D (2013) Obama: No 'sugarcoating' problems with health website. CNN.

- 23. World Health Organization (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS (2005) Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 43: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, Ashok M, Blalock SJ, Wines RC, et al. (2012) Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 157(11): 785–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DiMatteo MR (2004P) Variations in Patients' Adherence to Medical Recommendations. Medical Care, 42, 200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lorish CD, Richards B, Brown S (1989) Missed medication doses in rheumatic arthritis patients: intentional and unintentional reasons. Arthritis Care Res 2: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Daleboudt GM, Broadbent E, McQueen F, Kaptein AA (2011) Intentional and unintentional treatment nonadherence in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van den Bemt BJ, Zwikker HE, van den Ende CH (2012) Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 8: 337–351. 10.1586/eci.12.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, et al. (2004) Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. The Lancet 364: 937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Lew RA, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, et al. (1997) The relationship of socioeconomic status, race, and modifiable risk factors to outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40: 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zivin K, Kales HC (2008) Adherence to depression treatment in older adults: a narrative review. Drugs Aging 25: 559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cunningham JA, Murphy M, Hendershot CS (2014) Treatment dismantling pilot study to identify the active ingredients in personalized feedback interventions for hazardous alcohol use: randomized controlled trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract 10: 1 10.1186/s13722-014-0022-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Binks M, van Mierlo T (2010) Utilization patterns and user characteristics of an ad libitum Internet weight loss program. J Med Internet Res 12: e9 10.2196/jmir.1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Mierlo T, Fournier R, Jean-Charles A, Hovington J, Ethier I, et al. (2014) I'll Txt U if I Have a Problem: How the Societe Canadienne du Cancer in Quebec Applied Behavior-Change Theory, Data Mining and Agile Software Development to Help Young Adults Quit Smoking. PLoS One 9: e91832 10.1371/journal.pone.0091832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolfswinkel JF, Furtmueller E, Wilderom CPM (2011) Using grounded theory as a method for rigorously reviewing literature. European Journal of Information Systems 22: 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC (2009) Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun 33: 197–207. 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R (2010) Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 105: 525–539. 10.1038/ajg.2009.685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bernal I, Domenech E, Garcia-Planella E, Marin L, Manosa M, et al. (2006) Medication-taking behavior in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 51: 2165–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Belcon MC, Haynes RB, Tugwell P (1984) A critical review of compliance studies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 27: 1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cramer JA (2004) A Systematic Review of Adherence With Medications for Diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 1218–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C (2001) A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clinical Therapeutics 23: 1296–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hill J (2005) Adherence with drug therapy in the rheumatic diseases Part two: measuring and improving adherence. Musculoskeletal Care 3: 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koneru S, Kocharla L, Higgins GC, Ware A, Passo MH, et al. (2008) Adherence to medications in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol 14: 195–201. 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31817a242a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li P, Blum MA, Von Feldt J, Hennessy S, Doshi JA (2010) Adherence, discontinuation, and switching of biologic therapies in medicaid enrollees with rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health 13: 805–812. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Goycochea-Robles MV, et al. (2011) Statin discontinuation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 1020–1024. 10.1136/ard.2010.142455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Julian LJ, Yelin E, Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Trupin L, et al. (2009) Depression, medication adherence, and service utilization in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 61: 240–246. 10.1002/art.24236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carter CT, Waters HC, Smith DB (2011) Impact of infliximab adherence on Crohn's disease-related healthcare utilization and inpatient costs. Adv Ther 28: 671–683. 10.1007/s12325-011-0048-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kane S, Shaya F (2008) Medication non-adherence is associated with increased medical health care costs. Dig Dis Sci 53: 1020–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitiative reserach. New York: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Strauss AL, Corbin J (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Strauss AL, Corbin J (1998) Basics of Qualitative Resaerch: Techniques and Procedures for Developing GRounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Charmaz K (1990) ‘Discovering’ chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science and Medicine 30: 1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339: b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Blum MA, Koo D, Doshi JA (2011) Measurement and rates of persistence with and adherence to biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Ther 33: 901–913. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, Hale ED, Douglas KM, Kitas GD (2006) 'Compliance' is futile but is 'concordance' between rheumatology patients and health professionals attainable? Rheumatology (Oxford) 45: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Garcia-Gonzalez A, Richardson M, Garcia Popa-Lisseanu M, Cox V, Kallen MA, et al. (2008) Treatment adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 27: 883–889. 10.1007/s10067-007-0816-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Moss AC, Chaudhary N, Tukey M, Junior J, Cury D, et al. (2010) Impact of a patient-support program on mesalamine adherence in patients with ulcerative colitis--a prospective study. J Crohns Colitis 4: 171–175. 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ting TV, Kudalkar D, Nelson S, Cortina S, Pendl J, et al. (2012) Usefulness of cellular text messaging for improving adherence among adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 39: 174–179. 10.3899/jrheum.110771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shariff SZ, Bejaimal SAD, Sontrop JM, Iansavichus AV, Haynes RB, et al. (2013) Retrieving Clinical Evidence: A Comparison of PubMed and Google Scholar for Quick Clinical Searches. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15: e164 10.2196/jmir.2624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Corbin JM, Strauss A (1990) Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 13: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Binks M, van Mierlo T, Edwards CL (2012) Relationships of the psychological influence of food and barriers to lifestyle change to weight and utilization of online weight loss tools. Open Med Inform J 6: 9–14. 10.2174/1874431101206010009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ruiz P, Ruiz PP (1983) Treatment compliance among Hispanics. Journal of Operational Psychiatry 14: 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Garcia Popa-Lisseanu MG, Greisinger A, Richardson M, O'Malley KJ, Janssen NM, et al. (2005) Determinants of treatment adherence in ethnically diverse, economically disadvantaged patients with rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol 32: 913–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ediger JP, Walker JR, Graff L, Lix L, Clara I, et al. (2007) Predictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 102: 1417–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B (2005) Medication adherence and persistence: A comprehensive review. Advances in Therapy 22: 313–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lambert M, Conus P, Eide P, Mass R, Karow A, et al. (2004) Impact of present and past antipsychotic side effects on attitude toward typical antipsychotic treatment and adherence. Eur Psychiatry 19: 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McHorney CA, Schousboe JT, Cline RR, Weiss TW (2007) The impact of osteoporosis medication beliefs and side-effect experiences on non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Curr Med Res Opin 23: 3137–3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Horne R (2006) Compliance, adherence, and concordance: implications for asthma treatment. Chest 130: 65S–72S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Trotta MP, Ammassari A, Melzi S, Zaccarelli M, Ladisa N, et al. (2002) Treatment-related factors and highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 31 Suppl 3: S128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bermejo F, Lopez-San Roman A, Algaba A, Guerra I, Valer P, et al. (2010) Factors that modify therapy adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 4: 422–426. 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lakatos PL, Czegledi Z, David G, Kispal Z, Kiss LS, et al. (2010) Association of adherence to therapy and complementary and alternative medicine use with demographic factors and disease phenotype in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 4: 283–290. 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lorish CD, Richards B, Brown S Jr. (1990) Perspective of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis on issues related to missed medication. Arthritis Care Res 3: 78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Marengo MF, Waimann CA, de Achaval S, Zhang H, Garcia-Gonzalez A, et al. (2012) Measuring therapeutic adherence in systemic lupus erythematosus with electronic monitoring. Lupus 21: 1158–1165. 10.1177/0961203312447868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Horne R, Parham R, Driscoll R, Robinson A (2009) Patients' attitudes to medicines and adherence to maintenance treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 15: 837–844. 10.1002/ibd.20846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Richards JS, Cannon GW, Hayden CL, Amdur RL, Lazaro D, et al. (2012) Adherence with bisphosphonate therapy in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64: 1864–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Manchanda P, Wittink DR, Ching A, Cleanthous P, Ding M, et al. (2005) Understanding Firm, Physician and Consumer Choice Behavior in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Marketing Letters 16: 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- 78. McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB (2002) Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA 288: 2868–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, van der Temple H, van der Linden S (1999) Development of a Questionnaire to Investigate Patient Compliance with Antrirheumatic Drug Therapy. J Rheumatol 26: 2635–2641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA (2000) Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res 42: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ (2008) Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 10: 348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 82. Bardwell WA (2002) Rheumatoid Arthritis Severity Scale: a brief, physician-completed scale not confounded by patient self-report of psychological functioning. Rheumatology 41: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cunningham JA, Wild TC, Cordingley J, van Mierlo T, Humphreys K (2009) A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for alcohol abusers. Addiction 104: 2023–2032. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02726.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Farvolden P, McBride C, Bagby RM, Ravitz P (2003) A Web-based screening instrument for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care. J Med Internet Res 5: e23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X (2008) Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD000011 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. van den Bemt BJ, den Broeder AA, van den Hoogen FH, Benraad B, Hekster YA, et al. (2011) Making the rheumatologist aware of patients' non-adherence does not improve medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 40: 192–196. 10.3109/03009742.2010.517214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information Files.