Abstract

Runx1 is a transcription factor essential for definitive hematopoiesis, and genetic abnormalities in Runx1 cause leukemia. Runx1 is functionally promiscuous and acts as either an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene in certain epithelial cancers. Recent evidence suggests that Runx1 is an important factor in breast cancer, however its role remains ambiguous. Here, we addressed whether Runx1 has a specific pathological role during breast cancer progression and show that Runx1 has an oncogenic function. We observed elevated Runx1 expression in a subset of human breast cancers. Furthermore, throughout the course of disease progression in a classical mouse model of breast cancer (i.e., the MMTV-PyMT transgenic model), Runx1 expression increases in the primary site (mammary gland) and is further upregulated in tumors and distal lung metastatic lesions. Ex vivo studies using tumor epithelial cells derived from these mice express significantly higher levels of Runx1 than normal mammary epithelial cells. The tumor cells exhibit increased rates of migration and invasion, indicative of an aggressive cancer phenotype. Inhibition of Runx1 expression using RNA interference significantly abrogates these cancer-relevant phenotypic characteristics. Importantly, our data establish that Runx1 contributes to murine mammary tumor development and malignancy and potentially represents a key disease-promoting and prognostic factor in human breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Keywords: Runx1, breast cancer progression/metastasis, MMTV-PyMT

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide, accounting for almost a quarter of all cancers and 14% of cancer deaths (Jemal et al., 2011). Metastasis is often a fatal step in breast cancer progression, characterized by tumor cell intravasation, survival in circulation, and extravasation to distal sites such as the lung (Langley and Fidler, 2007). Perou and colleagues established over a decade ago that breast cancer progression and metastasis are intimately coupled with specific complex molecular transcriptional programs and downstream signaling pathways (Perou et al., 2000). In order to realize effective targeting of such molecular components for therapeutic benefit, it is vital that a more extensive understanding of the dysregulated molecular pathology of breast cancer is achieved.

Transcription factors are master regulators of signaling pathways in both normal and abnormal physiological processes, and have been shown to play key roles in cancer (Vaquerizas et al., 2009). Runt-related transcription factor 1 (Runx1, also known as AML1, CBFα2 or PEBP2αB) is one of a family of three transcription factors – Runx1, Runx2 and Runx3 – each associated with specific human cancers (Ito, 2004, Cameron and Neil, 2004, Chuang et al., 2013, Blyth et al., 2005). Runx1 functions as an activator or repressor of transcription by binding DNA through the Runt domain in complex with its binding partner core binding factor β (CBFβ) (Speck and Terryl, 1995). Runx1 regulates a variety of physiological processes, including cell survival, proliferation, differentiation and cell cycle progression and is most recognized for its role in hematopoiesis and leukemia (Blyth et al., 2005, Friedman, 2009, Mikhail et al., 2006, Ichikawa et al., 2013, Lambert et al., 2012). Recent reports have associated Runx1 with breast cancer (Janes, 2011, Chimge and Frenkel, 2013, Kadota et al., 2010, van Bragt et al., 2014, Taniuchi et al., 2012, Ferrari et al., 2014), and genome-wide sequencing of cohorts of breast cancer patients revealed it is one of the most prominently mutated and/or deleted genes in breast cancer (2012, Ellis et al., 2012, Banerji et al., 2012).

This study addresses if Runx1 expression correlates with breast cancer progression and metastasis and if Runx1 is important for maintenance of a cancer-related cell phenotype. To this end, a clinically informative in vivo mouse model for mammary tumor development that permits molecular and histological analysis of tumor progression and metastasis as well as complementary cell models were investigated (Chimge and Frenkel, 2013, Taniuchi et al., 2012, Janes, 2011, Wotton et al., 2002, Cheon and Orsulic, 2011, Lin et al., 2003). In the transgenic mouse model used, mammary gland specific expression of a polyoma middle T-antigen (PyMT) transgene is achieved using the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter (Guy et al., 1992). The potent PyMT oncoprotein, which acts as a membrane scaffold protein, impacts on signal transduction pathways that are also altered in human breast cancer including the Ras/Raf/MEK and PI3K/Akt pathways (Rodriguez-Viciana et al., 2006). This results in a disease progression similar to human breast cancer, with the development of multiple mammary adenocarcinomas as well as metastatic lesions in the lung with almost 100% penetrance (Lin et al., 2003). MMTV-PyMT mice develop well-differentiated, luminal-type adenomas that progress to metastatic, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma within 15 weeks (Lin et al., 2003, Herschkowitz et al., 2007). One of the major advantages of this model is that it can be used to study both primary mammary tumor development and metastasis.

Here, we confirmed the clinical relevance of Runx1 in breast cancer. Significantly, our in vivo interrogation of the MMTV-PyMT mouse model demonstrates that Runx1 expression increases concomitant with disease progression. Moreover, complementary in vitro studies establish that Runx1 is associated with higher migration and invasion ability; the knockdown of Runx1 supports its functional role in contributing to maintenance of a more aggressive tumor cell phenotype. Thus, these studies reveal the oncogenic potential of Runx1 in the progression and metastasis of breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols and the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female FVB/NJ mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were crossed with male FVB mice that were transgenic (+/−) for PyMT antigen under the control of the MMTV promoter. Genotyping was performed by PCR as described previously for the PyMT transgene (Guy et al., 1992). Female mice from this cross that were PyMT+/− were saved for further analysis. Mice were sacrificed at 4, 8, 10, 12, 13 and 15 weeks of age and whole mammary glands, tumor (if present) and/or lungs excised. The 15 week time point was considered to be the time point shortly before tumor burdens in mice reached a humane end point. To avoid non-biological variation, mice were sacrificed (and processed) at random ages from different litters at different times. Portions of tissues were either snap frozen for RNA extraction or fixed in 10% Zinc-Formalin solution and paraffin embedded for histological analysis.

Immunohistochemistry and semi-quantitative analysis

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded mammary gland, tumor and lung tissues from MMTV-PyMT mice were sectioned at 4μm on a Leica 2030 paraffin microtome (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Before immunohistochemical procedures were carried out, routine hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on each sample (Fischer et al., 2008).

The same immunohistochemical procedure was carried out for both the human tissue microarray and mouse tissue sections, except that only the mouse tissues were baked for one hour at 60°C. Following deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen retrieval was performed using DAKO Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA), pH6.0 in 50% glycerol at 95°C for 20 minutes. Sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase using hydrogen peroxide in methanol followed by treatment with 1% bovine serum albumin, 10% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. The tissue was incubated overnight at room temperature with anti-AML1 antibody (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). The anti-AML1 antibody was validated to confirm its specificity (Supplementary Material Fig. S1A). The reaction was visualized using VectaStain ABC Elite Rabbit IgG and DAB (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured on an Olympus BX50 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) using a QImaging Retiga 2000R camera with attached CRI color filter (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). One positive and two negative controls were included with each staining procedure (Supplementary Material Fig. S1B).

Semi-quantitative analysis of Runx1 in the human breast cancer tissue microarray (Catalog # BR1503b; US Biomax, Rockville, MD, USA) was achieved in three different ways: 1) by assessment of the presence or absence of Runx1 staining; 2) by assessment of the Runx1 staining intensity, graded on a scale of None, Weak, Moderate and Strong; and 3) by estimation of the % of Runx1 positive cells present (See Table 1 and Supplementary Material Fig. S2). Staining was graded in a blind manner by two independent investigators (GB & NMB), with inter-observer agreement found to be substantial with a kappa value of 0.75 (Cohen’s kappa coefficient test).

Table 1.

Runx1 and other clinic-pathologic characteristic of normal and breast cancer tissues from a tissue microarray (n = 140 total)

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of normal cases (% of total) | No. of DCIS cases (% of total) | No. of IDC cases (% of total) | |

| User determined | |||

|

| |||

|

Runx1 status

|

|||

| Negative | 1 (17%) | 7 (50%) | 34 (28%) |

| Positive

|

5 (83%) | 7 (50%) | 86 (72%) |

|

Runx1 staining

|

|||

| None | 1 (17%) | 7 (50%) | 34 (28%) |

| Weak | 1 (17%) | 3 (21%) | 45 (37%) |

| Moderate | 2 (33%) | 4 (29%) | 27 (23%) |

| Strong

|

2 (33%) | 0 | 14 (12%) |

|

% of Runx1 positive cells

|

|||

| ≤ 10% | 5 (100%) | 3 (42%) | 23 (27%) |

| 11–40% | 0 | 2 (29%) | 32 (37%) |

| 41–79% | 0 | 2 (29%) | 16 (19%) |

| ≥ 80% | 0 | 0 | 15 (17%) |

|

| |||

| BioMax determined | |||

|

| |||

|

Age

|

|||

| ≤ 50 | 4 (67%) | 8 (57%) | 52 (43%) |

| ≥ 50

|

2 (33%) | 6 (43%) | 68 (57%) |

|

Histologic grade

|

|||

| 1 (well differentiated) | - | - | 8 (7%) |

| 2 (moderately differentiated) | - | - | 89 (74%) |

| 3 (undifferentiated)

|

- | - | 15 (13%) |

|

ER

|

|||

| Negative | 1 (17%) | 10 (71%) | 81 (68%) |

| Positive

|

5 (83%) | 4 (29%) | 39 (32%) |

|

PR

|

|||

| Negative | 2 (33%) | 8 (57%) | 90 (75%) |

| Positive

|

4 (67%) | 6 (43%) | 30 (25%) |

|

HER2

|

|||

| Negative | 6 (100%) | 14 (100%) | 95 (79%) |

| Positive

|

0 | 0 | 25 (21%) |

|

AR

|

|||

| Negative | 0 | 12 (86%) | 82 (68%) |

| Positive

|

6 (100%) | 2 (14%) | 38 (32%) |

|

Ki67

|

|||

| Negative | 6 (100%) | 14 (100%) | 65 (54%) |

| Positive

|

0 | 0 | 55 (46%) |

|

p53

|

|||

| Negative | 3 (50%) | 9 (64%) | 40 (33%) |

| Positive | 3 (50%) | 5 (36%) | 80 (67%) |

IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; cyst., cystsarcoma; ER, estrogen recepor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; AR, androgen receptor

Runx1-stained mouse sections were evaluated based on immunoreactivity and scored on a staining scale system of absent (0) to strong (+4), with each score associated with an arbitrary value for graphical representation of the data (Buesa, 2005). Following staining procedures (as described), sections were scored as follows: absence of staining received a negative (−/0) designation and positive staining received a +1/25, +2/50, +3/75, or +4/100 score. A panel with images representing the above staining classification scores was created as a reference for each tissue (Supplementary Material Fig. S1C); subsequently, all images were scored based on the aforementioned reference/classification system. Sections were randomly selected from n = 3 animals per time point per group per tissue and were evaluated blindly by two independent investigators (GB & NMB) with <5% deviation in results from the two independent investigators.

Cell culture

The mouse MMTV cell line, a tumor epithelial cell line derived from the tumor of a 13 week old PyV-MT+/− female mouse, was obtained from Dr. Leslie M. Shaw (University of Massachusetts Medical School) who developed the cell line (Nagle et al., 2004). These cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. The NMuMG normal mouse mammary epithelial cell line were purchased from and validated by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). These cells were cultured following instructions from ATCC and used within six months of purchase. Media and supplements were obtained from Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, unless otherwise stated. All cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

siRNA transfection

MMTV cells (~60–70% confluent) were transfected with control non-silencing siRNA (siNS – 500nM) or the On-Target Plus Mouse Runx1 siRNA smartpool (Thermo Scientific, Lafayette, CO, USA) (siRunx1 – 500nM) using Lipofectamine2000 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Controls in which cells were exposed to Lipofectamine2000 only (Mock) were also included where indicated. Gene and protein knockdown of Runx1 was assessed 48 hours after transfection, and growth, migration and invasion assays were initiated 24 hours after transfection (‘0 hours’ time point).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from mouse tissues and cell lines using Trizol according to manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and purified with a Zymo RNA purification kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System according to manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and gene specific primers (Runx1 3′: GGCCATGAAGAACCAGGTAG; Runx1 5′: CAACTTGTGGCGGATTTGTA; RPL19 3′: TTGCCTCTAGTGTCCTCCGC; RPL19 5′: GGGAATGGACAGTCACAGGC) in an Applied Biosystems Viia 7 system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After normalization to the reference gene (as indicated), relative expression levels of each target gene were calculated using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell protein lysates were generated using RIPA buffer; nuclear and cytoplasmic protein lysates were generated using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Thermo Scientific, Lafayette, CO, USA). Both protein isolation reagents were supplemented with 25μM MG132 and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Lysates were separated on a 10% acrylamide gel and immobilized on PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Blots were blocked using 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) before being incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-AML1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000) and anti-GAPDH (rabbit monoclonal, 1:5000) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti-Lamin A/C (goat polyclonal, 1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). GAPDH and Lamin A/C were used as loading controls. Secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) were used to detect proteins in conjunction with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit and Chemidoc XRS+ imaging system (both Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Migration assays

For the scratch assay, 3.5 × 105 MMTV and NMuMG cells were seeded in duplicate in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were serum-starved for 8hrs prior to beginning the assay as follows: At 95–100% cell confluency, a scratch was made using a pipette tip and cell migration monitored by taking pictures at indicated time points post-scratch. The area of the scratch was quantified using the MiToBo plug-in for ImageJ software and plotted as a percentage of total area for each of three independent experiments. For studies using siRNAs, the same procedure was performed with the following exceptions: 2 × 105 MMTV cells were seeded and transfected (as described) the following day; the scratch was made 24–48 hours later when cells reached 95–100% confluence.

For the trans-well migration assay, 5 × 104 MMTV and NMuMG cells were seeded in triplicate in migration chambers (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) in serum-free medium. Cells were allowed to migrate through 8μm pores toward medium containing 10% FBS for 48 hours. Non-migrating cells were removed and cells that migrated through the membrane were fixed with ice-cold 100% methanol. Fixed cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution and photographed before solubilizing the stain with 10% glacial acetic acid and measuring absorbance at 595nm in three independent experiments. For studies using siRNAs, the same procedure was followed with the following exceptions: 2 × 105 MMTV cells were seeded and transfected (as described) the following day. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were trypsinized and seeded in migration chambers as described above.

Analysis of cell invasion

For the invasion assay, 5 × 104 MMTV and NMuMG cells were seeded in triplicate in growth factor reduced Matrigel invasion chambers (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) in serum-free medium. Cells were allowed to invade through the Matrigel and 8μm pores toward medium containing 10% FBS for 48 hours. Non-invading cells were removed using a cotton swab and cells that invaded through the membrane were fixed with ice-cold 100% methanol. The procedure for trans-well migration described above was then followed to complete the experiments.

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistically significant differences were determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests where indicated. In all cases, P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Runx1 expression is increased in a subset of human breast cancers and increases with disease progression in mammary glands of MMTV-PyMT mice

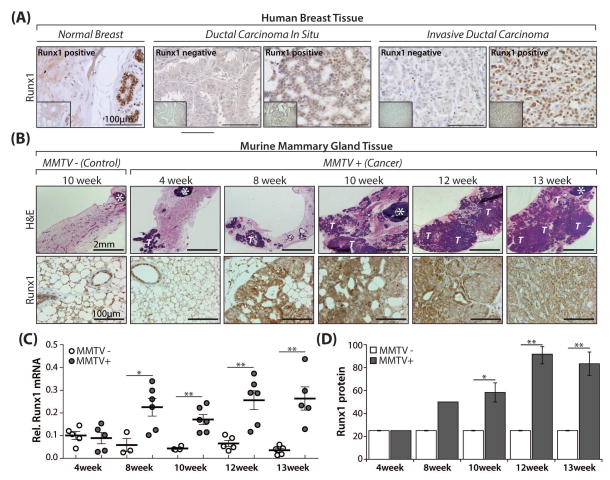

To address the clinical relevance and pathological role of Runx1 in breast cancer progression and metastasis, we initially conducted a pilot study to determine Runx1 protein expression in a human breast cancer tissue microarray (TMA) as well as Runx1 RNA expression in a relevant publicly available dataset. As shown in Fig. 1A, Runx1 is present in the epithelial cells of the normal breast. Notably, Runx1 expression was detected and elevated in a subset of breast tissue disease states including ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal carcinoma. Moreover, in cancerous tissues where Runx1 was present, the percentage of Runx1 positive cells was substantially more than in normal breast tissue suggesting a role for Runx1 in breast cancer (Fig. 1A and Table 1). To complement data obtained from analysis of Runx1 expression in the TMA, an Agilent gene expression microarray dataset generated by Gluck et al (Gluck et al., 2012) that contained 154 invasive breast carcinoma cases and 4 normal breast tissues was analyzed (available at www.oncomine.org). Probing of this dataset revealed that 75% (3/4) of normal breast and 96% (148/154) of invasive breast cancer samples expressed Runx1. Importantly, of the Runx1-expressing invasive breast carcinoma cases, 72% (107/148) expressed more Runx1 than the average reported for normal breast samples (Supplementary Material Fig. S3). Taken together, these findings prompted us to further investigate Runx1 in breast cancer using the MMTV-PyMT transgenic mouse model in order to examine Runx1 expression at multiple time points during disease progression and metastasis.

Fig. 1. Runx1 expression during breast cancer progression in a sub-set of human breast cancer patient samples and the mammary gland of MMTV-PyMT mice.

(A) Representative images from Runx1 immunohistochemical staining of a human breast cancer tissue microarray containing normal breast as well as Runx1 positive and negative breast cancer patient samples (scale bar 100μm; mag. 40x). Insets (bottom left, boxed off region) are lower magnification (20x) images of respective cores to show a more global view of individual breast cancer samples. (B) H&E (upper panels; scale bar 2mm; mag. 2x) and Runx1 (lower panels; scale bar 100μm; mag. 40x) staining of representative mammary glands from mice positive for the transgene (MMTV+) at multiple time points (4, 8, 10, 12 and 13 weeks) representing early (~4–8 weeks), mid (~8–12 weeks), and late (~12–15 weeks) stage breast cancer disease progression. A representative negative control (MMTV−) at 10 weeks is also shown. (C) Scatter plot showing qRT-PCR of Runx1 RNA expression at time points indicated in mammary glands from diseased (MMTV+) and age-matched negative control (MMTV−) mice with N = 3–5 and N = 5–6 mice per time-point per MMTV− and MMTV+ group, respectively. Expression levels are relative to the control gene RPL19. (D) Semi-quantitative analysis of Runx1 protein expression as assessed by scoring immunohistochemically processed mammary glands from n = 3 representative mice per time point per group. All quantitative/semi-quantitative data are depicted as mean ± S.E. per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (student’s t-test). White T = transformed/tumor tissue; white * = lymph node.

To determine the changes in Runx1 expression at the primary site of cancer initiation, mammary glands from mice positive for the transgene (MMTV+) and age-matched negative control mice (MMTV−) were sacrificed at 4, 8, 10, 12, and 13 weeks of age. These time points represent early through late stages of disease progression. Mammary glands from MMTV+ mice at 15 weeks were not used in this analysis because the mammary gland could not be cleanly excised separate from the tumor due to the extent of tumor involvement.

H&E staining of mammary glands (Fig. 1B, upper panels) shows the morphological changes during disease progression and is in line with previously published work (Lin et al., 2003). The morphology of mammary glands from control mice (MMTV−) did not change significantly over time (other than moderately increasing in size with age) and therefore one image from a representative mouse mid-way through the time course (10 weeks) is shown (Fig. 1B). Runx1 staining was present at consistently low levels in MMTV− mammary luminal epithelial cells only. In contrast, Runx1 expression in MMTV+ mammary glands increased concomitant with disease progression, with strong nuclear expression evident at 13 weeks (Fig. 1B, lower panels). This observation was validated when gene and protein expression were evaluated: Runx1 RNA levels remained at steady-state low levels in MMTV− mice and increased significantly over controls at almost all time points in MMTV+ mice (P<0.05, Fig. 1C). Further, semi-quantitative analysis was performed on Runx1 immunostained tissues and protein levels remained consistently low in MMTV− mice over 13 weeks (Fig. 1D). Conversely, elevated Runx1 persisted in MMTV+ mice and was significantly increased over MMTV− mice at almost all time points (P<0.05, Fig. 1D).

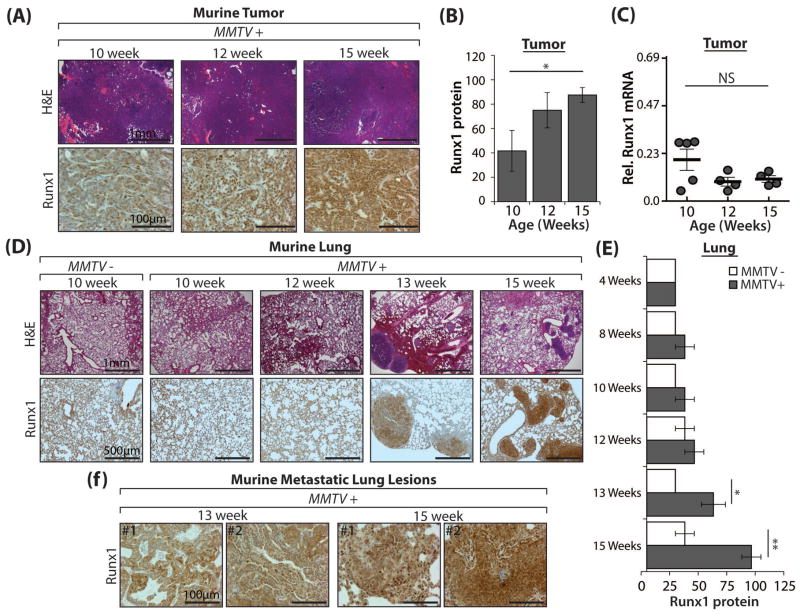

Tumors and metastatic lung lesions from MMTV-PyMT mice express high levels of Runx1

Given the finding of increased Runx1 in both a subset of human breast tumors (Fig. 1A and Table 1) and throughout disease progression in the mammary gland of MMTV+ mice (Fig. 1B–D), the expression of Runx1 in the associated tumors was further evaluated. Tumors were excised at three time points representing early (10 weeks), mid (12 weeks) and late (15 weeks) stage tumor progression. Analysis of H&E staining of tumor sections revealed sheets of transformed epithelial cells, which became more densely packed as the tumor developed over the course of 5 weeks (Fig. 2A, upper panels). Positive nuclear Runx1 staining was detected in tumor epithelium at all time points examined and increased with tumor development (Fig. 2A, lower panels; Fig. 2B). Semi-quantitative analysis of Runx1 immunostaining demonstrated a trend for increasing Runx1 protein levels over time; however, this change was only significant (P<0.05) at the latest time point when compared with the earliest (15 vs. 10 weeks) (Fig. 2B). Similar to protein levels, Runx1 RNA expression did not change significantly over time yet remained elevated (at a level comparable with that of MMTV+ mammary glands), particularly at later time points (12 and 15 weeks), suggesting Runx1 involvement throughout tumor development (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Runx1 expression in MMTV-PyMT breast tumors and metastatic lung lesions.

(A) H&E (upper panels; scale bar 1mm; mag. 4x) and Runx1 (lower panels; scale bar 100μm; mag. 40x) staining of representative tumors at early (10 weeks), mid (12 weeks), and late (15 weeks) stage tumor progression. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of Runx1 protein expression as assessed by scoring immunohistochemically processed tumors from n = 3–5 representative mice per time point per group. (C) Scatter plot showing qRT-PCR of Runx1 RNA expression at time points indicated in tumors from N = 4–5 MMTV+ mice per time point per group. Expression levels are relative to the control gene RPL19. NS = no significant difference, P>0.05. (D) H&E (upper panels; scale bar 1mm; mag. 4x) and Runx1 (lower panels; scale bar 500μm; mag. 10x) staining of representative lungs at time points indicated from MMTV+ mice and a representative 10 week negative control (MMTV−). (E) Semi-quantitative analysis of Runx1 protein expression as assessed by scoring immunohistochemically processed lungs from n = 3 representative mice per time point per group. (F) High magnification images of two representative MMTV+ mice (denoted #1 and #2) at 13 and 15 weeks (scale bar 100 μm; mag. 40x) highlighting significantly increased Runx1 expression in metastatic lesions. All quantitative data are depicted as mean ± S.E. per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (student’s t-test).

Lung and lymph nodes are the favored sites of metastasis in the MMTV-PyMT model. Previous work showed that lung metastases are readily observed both macroscopically and microscopically in MMTV-PyMT mice from about 12 weeks of age, with more lesions present at later time points (Guy et al., 1992, Franci et al., 2013). Therefore, to detect changes in Runx1 expression during the onset and progression of metastatic disease, MMTV+ and age-matched negative control lungs were examined histologically at four time points – 10, 12, 13 and 15 weeks – during which tumors were developing and growing. Similar to the mammary gland, although there was Runx1 expression in the MMTV− lung epithelium, levels of Runx1 did not change over time and so only one representative image from a 10 week old MMTV− mouse is shown (Fig. 2D). Metastasis was readily detectable by morphological assessment of H&E stained MMTV+ lung sections at 13 and 15 weeks, however no metastasis was detected at earlier time points (10 or 12 weeks) or in MMTV− mice (Fig. 2D, upper panels). Importantly, Runx1 expression increased significantly over controls at 13 and 15 weeks (P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively), with elevated Runx1 expression present in the multiple metastatic lesions in the lung, particularly at the latest stage assessed (15 weeks) (Fig. 2D–F). Higher magnification images of two different mice are shown to highlight the increased nuclear Runx1 expression in mice at 15 weeks, relative to 13 weeks in the metastatic cell deposits in the lung (Fig. 2F). The increased staining intensity at 15 weeks is consistent among all mice (n = 3) and reflects an increased number of stained cells per field of view (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Material Fig. S1). Collectively, these findings indicate a robust expression of Runx1 in the tumor cells that is retained in those cells which colonize in lung metastases.

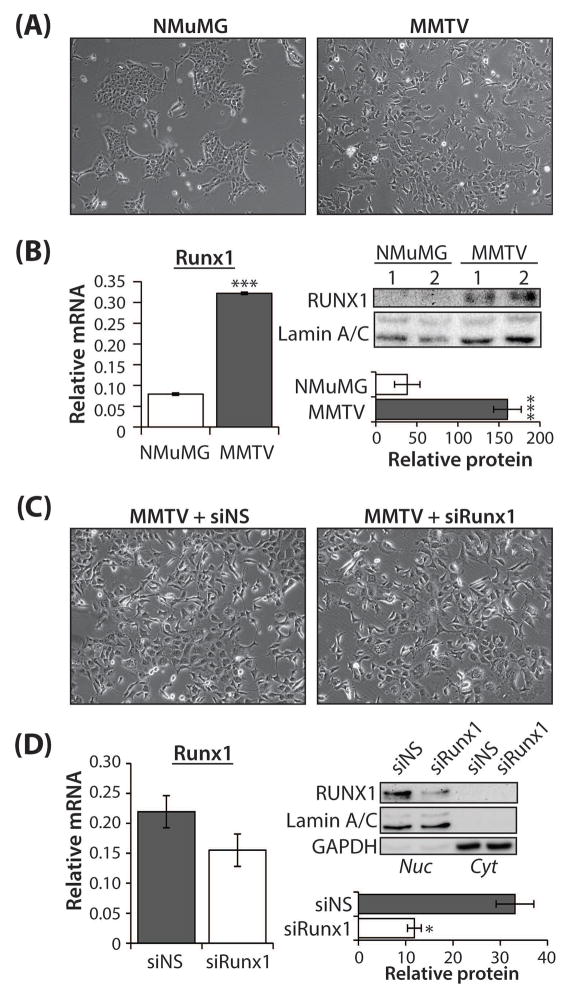

MMTV-PyMT tumor cells express markedly higher Runx1 than normal mammary gland cells

To determine if Runx1 contributed to any cancer-relevant phenotypes in breast cancer, an in vitro cell model complementary to the mouse model was used. The MMTV cells (Fig. 3A) are an epithelial tumor cell line derived from the tumor of a 13 week old MMTV-PyMT mouse (Nagle et al., 2004). The control cell line used was NMuMG (Fig. 3A), a normal mouse mammary gland epithelial cell line (Owens et al., 1974). Runx1 RNA expression was significantly higher in the MMTV cells than the NMuMG cells (P<0.001), with MMTV cells expressing 4-fold more Runx1 RNA than control cells (Fig. 3B, left). Similarly, Runx1 protein levels were 4-fold higher (P<0.001) in MMTV cells compared with NMuMG cells (Fig. 3B, right). The differences in Runx1 expression between these two cell lines were analogous with the differences seen in early versus late stage disease in the MMTV-PyMT+ mice (Fig. 1B–D and Fig. 2A–F), and thus were considered suitable for further studies.

Fig. 3. Characterization of Runx1 expression in normal breast epithelial cells (NMuMG) and tumor epithelial cells (MMTV), with and without Runx1 depletion.

(A) Phase contrast microscopy images (mag. 10x) of model cell lines to evaluate morphological differences in cells used in this study: NMuMG, normal mouse mammary gland epithelial cells and MMTV, tumor epithelial cells derived from the tumor of a 13 week old MMTV-PyMT+ mouse. (B) Left: qRT-PCR of Runx1 RNA expression in NMuMG and MMTV cells from N = 3 independent samples performed in triplicate. Values are shown relative to RPL19. Right, upper: representative western blot demonstrating endogenous Runx1 expression in two independent samples from NMuMG and MMTV cell lines. Lamin A/C was used as the loading control. Right, lower: Runx1 protein quantitation (plotted relative to Lamin A/C control) from N = 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate. (C) MMTV cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA (siNS) or Runx1-targeting siRNA smartpool (siRunx1) were subject to phase contrast microscopy. Images (mag. 10x) of transfected cells were used to evaluate any morphological changes present. (D) Left: qRT-PCR of Runx1 RNA expression in siNS- or siRunx1-transfected MMTV cells from N = 3 independent samples performed in triplicate. Values are shown relative to RPL19. Right, upper: representative western blot demonstrating nuclear (Nuc) and cytoplasmic (Cyt) Runx1 protein expression in MMTV cells transfected as above. Lamin A/C and GAPDH were used as the loading control for Nuc and Cyt Runx1 protein expression, respectively. Right, lower: Runx1 protein quantitation (plotted relative to Lamin A/C control) from N = 3 independent experiments. All quantitative data are depicted as mean ± S.E. per group. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 (student’s t-test).

To reveal the significance of high Runx1 expression in the MMTV cells, siRNAs were used to diminish Runx1 expression. Morphological changes as a result of expressing siNS or siRunx1 were not observed (Fig. 3C). RNA and protein levels were measured from MMTV cells transfected with either a non-silencing control siRNA (siNS) or a Runx1 siRNA smartpool (siRunx1) to determine knockdown efficacy (Fig. 3D). The level of Runx1 RNA expression in the siRunx1-transfected cells was reduced (Fig. 3D, left panel) and the siRunx1-transfected cells expressed almost 70% less Runx1 protein than the siNS control (P<0.05) (Fig. 3D, right panel). Moreover, Runx1 was present almost exclusively in the nuclear protein fraction (Fig. 3D, right panel).

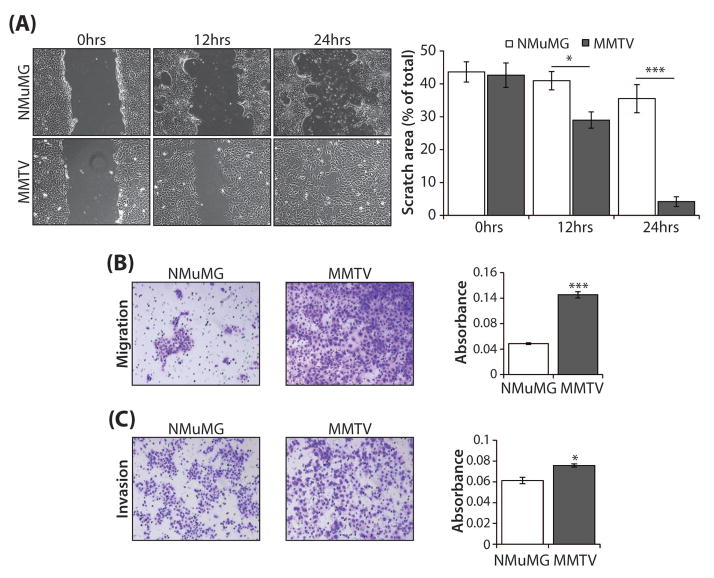

MMTV cells exhibit significantly greater ability to migrate and invade than normal mammary gland cells

As Runx1 expression was strongly associated with tumor growth and metastasis in the MMTV-PyMT model of breast cancer, we proposed that the Runx1-expressing MMTV cells may have a more aggressive cancer-related phenotype. To test this hypothesis, the ability of MMTV cells to migrate and invade was evaluated in comparison with the NMuMG control cells. In a scratch assay, MMTV cells demonstrated a significantly higher ability to migrate than controls at both 12 hours (P<0.05) and 24 hours (P<0.001) post-scratch, as determined by measuring the area of the scratch at the time points indicated (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these findings, the ability of MMTV cells to migrate in a trans-well assay was significantly greater (2.5-fold, P<0.001) than that of NMuMG cells (Fig. 4B). Moreover, using an invasion assay, the ability of MMTV cells to invade through a matrigel-coated membrane was significantly higher (P<0.05) than that of NMuMG cells (Fig. 4C). To complement the representative field of view images (Fig. 4B, C, right panel), quantitation of migration/invasion by measurement of the absorbance of solubilized crystal violet stain retained by migrated/invaded cells is shown (Fig. 4B, C, left panels) for the global representation of the wells. Together, these studies demonstrate that robust Runx1 expression is associated with a more aggressive cancer-related cell phenotype.

Fig. 4. Evaluation of migration and invasion ability in NMuMG and MMTV cells.

(A) Representative phase contrast images (magnification 100x) of NMuMG and MMTV cells subjected to a scratch assay for times indicated. The area of the scratch was plotted as a percentage of total area for N = 3 independent experiments carried out in duplicate. (B) Light microscopy images (mag. 12x) of stained cells from a representative (1 of N = 3) trans-well migration assay experiment with NMuMG and MMTV cells (left); quantitation of migrated cells assessed by measurement of the absorbance of solubilized crystal violet stain retained by migrated cells (right). (C) Light microscopy images (mag. 12x) of stained cells from a representative (1 of N = 3) trans-well matrigel invasion assay experiment with NMuMG and MMTV cells to evaluate invasion (left); quantitation of invaded cells assessed by measurement of the absorbance of solubilized crystal violet stain retained by invaded cells (right). For all assays, three independent experiments were carried out in triplicate. All quantitative data are depicted as mean ± S.E. per group. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 (student’s t-test).

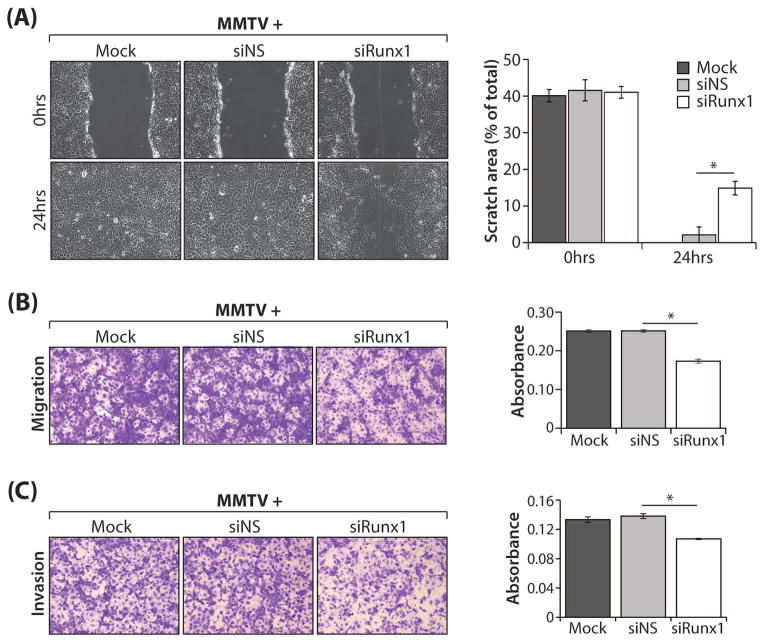

Runx1 depletion in MMTV cells significantly diminishes cancer-promoting migration and invasion phenotypes

The strongest cancer-associated phenotypes demonstrated for MMTV cells were their superior migration and invasion abilities (Fig. 4A–C). Thus, we postulated that these characteristics would be modulated upon Runx1 depletion. Consistent with this hypothesis, the ability of siRunx1-transfected MMTV cells to migrate as well as to invade was significantly reduced compared with controls (Fig. 5A–C). Fig. 5A shows representative images of the scratch assay, both at the time of the scratch and 24 hours later; clearly, siRunx1-transfected cells have a decreased ability to migrate (Fig. 5A, left). The images are corroborated by associated quantitative analysis that confirmed migration of Runx1-depleted cells was significantly reduced compared with the siNS control (P<0.05) (Fig. 5A, right). Likewise, migration of siRunx1-transfected cells in a trans-well migration assay was significantly less (P<0.05) than the control cells, as evidenced by representative images and quantitative data shown in Fig. 5B. Moreover, invasion was significantly inhibited relative to controls (P<0.05) when Runx1 expression was decreased in MMTV cells (Fig. 5C). In summary, these findings confirm the oncogenic potential of Runx1 in breast cancer cells.

Fig. 5. Effect of Runx1 depletion on migration and invasion ability of MMTV cells.

MMTV cells treated with transfection reagent only (Mock) or transfected with non-targeting siRNA (siNS) or Runx1-targeting siRNA smartpool (siRunx1) were assayed as follows: (A) Representative phase contrast images (mag. 10x) of MMTV cells treated as above were subjected to a scratch assay for times indicated. The area of the scratch was plotted as a percentage of total area for N = 3 independent experiments carried out in duplicate. (B) Light microscopy images (mag. 12x) of stained cells from a representative (1 of N = 3) trans-well migration assay experiment with MMTV cells treated as above (left); quantitation of migrated cells assessed by measurement of the absorbance of solubilized crystal violet stain retained by migrated cells (right). (C) Light microscopy images (mag. 12x) of stained cells from a representative (1 of N = 3) trans-well matrigel invasion assay experiment with MMTV cells treated as above to evaluate invasion (left); quantitation of invaded cells assessed by measurement of the absorbance of solubilized crystal violet stain retained by invaded cells (right). For all assays, three independent experiments were carried out in duplicate. All quantitative data are depicted as mean ± S.E. per group. *P<0.05 (student’s t-test).

Discussion

Runx protein function in cancer is dichotomous, because these proteins act as either tumor suppressors or oncogenes, depending on cellular context (Chimge et al., 2012, Pratap et al., 2009, Chimge and Frenkel, 2013, Wotton et al., 2002). The key findings of this study support an oncogenic function for Runx1 in breast cancer: Runx1 expression increases concomitant with disease progression in the mammary gland of MMTV-PyMT mice and is highly expressed in metastatic lesions in lung. Complementary in vitro studies demonstrate that Runx1 expression is significantly higher in tumor epithelial cells compared to normal epithelial control cells. Runx1 positive tumor cells exhibit a more aggressive phenotype, with significantly higher migration and invasion ability than control cells. Moreover, Runx1 knockdown in the MMTV cells results in a marked abrogation of the aggressive cancer-related phenotype. Thus, these data provide strong evidence indicating the oncogenic potential of Runx1 in breast cancer.

Recent genetic studies have highlighted a potential role for Runx1 in breast cancer (Scheitz et al., 2012, Banerji et al., 2012, Ellis et al., 2012), with one study reporting that Runx1 is in the top 1% of over-expressed genes in breast cancer based on a meta-analysis of microarray studies comparing Runx1 gene levels in tumor versus normal tissue (Scheitz et al., 2012). Our study examined Runx1 protein and RNA levels in normal human breast and breast cancer patient samples by immunohistochemical staining of tissue microarrays and analysis of publicly available microarray datasets, respectively. The results show that Runx1 is expressed not only in normal breast epithelium, but also highly expressed in some breast cancers. Our results are in line with a very recent study in which a comprehensive analysis of Runx1 protein in breast cancer patients was performed (Ferrari et al., 2014). It was found that high Runx1 expression significantly associated with poorer survival in a cohort of breast cancer patients.

Corroborating the immunohistochemical findings in human tissues, examination of Runx1 in the clinically informative MMTV-PyMT transgenic mouse model of breast cancer revealed that Runx1 expression in the mammary gland epithelium of diseased mice is increased over controls as early as 8 weeks, and further increases throughout breast cancer progression. This pattern of expression is consistent with studies in other cancers of epithelial origin. For example, Planaguma and colleagues demonstrated that Runx1 is overexpressed in invasive endometrial carcinoma in relation to cancer progression from normal atrophic endometrium through hyperplasia and subsequent carcinoma (Planaguma et al., 2004). We also show that Runx1 expression is consistently elevated in MMTV-PyMT breast tumors. This result agrees with data from other epithelial cancers such as epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), where Runx1 protein is overexpressed in high grade tumors in a study carried out on a cohort of 117 EOC patient samples (Keita et al., 2013). In contrast, one study reported down-regulation of the Runx1 gene in high grade vs. low grade breast tumors from a cohort of 29 breast tumor samples; however, this group did not investigate protein expression in these patients and the sample size was limited (Kadota et al., 2010). We further demonstrate that Runx1 is highly expressed in the multiple metastatic lesions found in the lungs of MMTV-PyMT mice. Consistent with this result, Runx1 has been shown to be over-expressed in EOC metastasis as well as endometrial cancer metastasis (Doll et al., 2009, Keita et al., 2013). Collectively, our in vivo data strongly suggests that Runx1 expression is intimately involved with breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Using a complementary in vitro tumor epithelial cell model derived from the MMTV-PyMT mouse (Nagle et al., 2004) (as well as a normal mouse mammary gland epithelial cell control), we evaluated cancer-related phenotypic properties of the cells including invasion and migration. The MMTV cells, which express 4-fold more Runx1 than the control cells, exhibit a significantly greater ability to migrate and invade compared with the control cells, and when Runx1 is knocked down in the MMTV cells, the phenotype is significantly diminished. This result is comparable with related studies in human ovarian cancer cells, where knockdown of Runx1 in SKOV3 cells inhibited migration and invasion (Keita et al., 2013).

Our finding that MMTV-derived tumor cells exhibit strong Runx1 expression is in line with our in vivo observations of robust Runx1 expression in tumors from MMTV-PyMT mice. We considered whether this increase in Runx1 expression was solely a consequence of differences in epithelial cell content between MMTV+ and MMTV− mice, particularly as the proportion of epithelial cells in the MMTV− mice was substantially lower. However, this is unlikely based on the similarity of Runx1 expression in our models and that of another study: Zhu et al performed expression profiling of mouse mammary tumor models including the MMTV-PyMT model, using pregnant mouse mammary glands as their control because they are highly enriched for epithelial cells (Zhu et al., 2011). Upon probing their dataset for Runx1 expression, we found the differences between tumor and control to be very much in line with our data. Indeed, we also see the same difference in Runx1 expression in our tumor vs normal epithelial cells in the in vitro model. This finding supports the idea that Runx1 is dysregulated in tumor epithelial cells and is an important player in breast cancer progression and metastasis.

Another of the Runx family members – Runx2 – has been shown in numerous studies to be involved in breast cancer metastasis, particularly to bone (Pratap et al., 2006, Pratap et al., 2005, Pratap et al., 2011). A recent study by Blyth’s group using an MMTV mouse model engineered to over-express Runx2 demonstrated that although development and differentiation in the mammary gland were perturbed, there was a lack of overt carcinoma and no effect on metastasis was reported (McDonald et al., 2014). It is interesting to postulate that this may be due to context-specific differential expression and function of Runx factors, where Runx2 may be more important in cancers that metastasize to bone and Runx1 may be more important in cancers that metastasize to lung. We propose that Runx1 exhibits pleotropic effects throughout breast cancer progression, being important in the malignant transformation of epithelial cells in the mammary gland and contributing to disease progression in breast cancer. Runx1 may play a significant role in a more aggressive disease phenotype by promoting migration and invasion of cancer cells during tumor development and metastasis.

Intriguingly, two very recent studies have associated Runx1 with hormonal status in breast cancer (Ferrari et al., 2014, van Bragt et al., 2014). This is particularly interesting in light of several genetic studies that drew attention to the clinical relevance of Runx1 and breast cancer, yet focused almost exclusively on Runx1 in human estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancers (Banerji et al., 2012, Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2012, Ellis et al., 2012). van Bragt et al reported that Runx1 is a key regulator of ER+ mammary luminal epithelial cells and their findings of Runx1 expression patterns in vivo are very much in line with our findings in normal breast and at the earliest stages of breast cancer development in the MMTV-PyMT model (van Bragt et al., 2014). Moreover, Ferrari et al reported data to suggest that Runx1 may contribute to tumor progression in ER− (and progesterone- (PR-) and HER2-) breast cancers (Ferrari et al., 2014). Of note, the MMTV-PyMT model is a luminal model of breast cancer and ER (as well as PR) status is reported to change throughout cancer progression: early stage disease is ER+ but this switches to ER− in the latest stages of disease (Kouros-Mehr et al., 2008, Lin et al., 2003). Also, the MMTV cells used in this study (derived from the tumor of a late-stage disease mouse) were found to be negative for ESR1 (encoding ERα) (G. Browne, unpublished observation). Thus, our findings that 1) Runx1 expression increases during disease progression and particularly at late stages in a mouse model that switches from ER+ to ER− and 2) the Runx1-high ER-MMTV breast cancer cells exhibit a more aggressive phenotype (abrogated upon Runx1 depletion) are clinically relevant. This conclusion is further supported by the strong correlation between Runx1 expression and poor prognosis in triple negative human breast cancer tissues (Ferrari et al., 2014).

The most striking results presented in this study establish the oncogenic potential of Runx1 in breast cancer: Runx1 is markedly associated with disease progression, tumor development and metastasis in the MMTV-PyMT model of breast cancer. Moreover, Runx1 is associated with maintenance of more aggressive cancer-associated characteristics and its depletion results in significant abrogation of this phenotype. In light of our findings and other recent reports, more in-depth investigations are warranted to fully appreciate the molecular mechanisms of Runx1 action in breast cancer. Indeed, some studies have begun to explore this potential: ablation of Runx1 in other epithelial cancers dramatically reduces tumor burden (Scheitz et al., 2012). Further, a recently discovered small-molecule inhibitor of the Runx1-CBFβ interaction is capable of reducing tumor burden in a murine leukemia model (Cunningham et al., 2012). These data, together with the results of this study, highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting the oncogenic activity of Runx1 in breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material Fig. S1. Runx1 IHC controls, antibody validation and reference image panels used for blind scoring and semi-quantitative assessment of mouse tissues. (A) The Runx1 antibody used for western blotting and IHC in both human and mouse tissue was validated to confirm is specificity in a number of ways: To confirm that the Runx1 antibody did not cross react with Runx2, another Runx protein family member, sequential sections from the mammary gland of an MMTV-PyMT mouse were stained with an antibody against Runx2 (rabbit polyclonal (M70) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) alongside the Runx1 antibody (left panel). As shown, the two antibodies stained distinctly different cells in the mammary gland: Luminal epithelial cells (denoted by a black L) were Runx1 positive and Runx2 negative, whereas myoepithelial cells (denoted by a black M) were Runx1 negative and Runx2 positive. Prostate tissue (known to express Runx2) was assessed for Runx1 and Runx2 expression (middle panel). Prostate epithelial cells expressed strong nuclear Runx2, whereas only weak staining of a small number of the same cells was seen for Runx1. Western blotting for Runx1 and Runx2 was performed in two independent whole cell lysate samples from NMuMG and MMTV mouse mammary gland cells (right panel, top). Distinctive expression patterns for both proteins were evident: NMuMG cells express high levels of Runx2 and very little Runx1 yet MMTV cells express high levels of Runx1 and very little (if any) Runx2. Human mammary adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (MCF7) either untransfected (Mock) or transfected with two different quantities of empty vector control (+Vector) or RUNX1 overexpression vector (+Runx1) were used as an independent validation (right panel, bottom). The same protocols used for IHC and western blotting using the Runx1 antibody were used for the Runx2 antibody (See Materials and Methods). Scale bar = 200μm. (B) Representative images of one positive tissue control and two negative reagent controls processed with each Runx1 IHC staining procedure demonstrating an optimized staining protocol, allowing for confidence in the accurate interpretation of results. Scale bar = 200μm. (C) Reference image panels used for blind scoring of the Runx1 IHC staining of the tissue samples from the MMTV-PyMT mouse model. Given that background staining in each tissue differed, a new panel of images representative of each score for each tissue was used to more accurately reflect changes in Runx1 expression in individual tissues. Scale bars = 500μm; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; DAB: 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine.

Supplementary Material Fig. S2. Reference image panels used for blind scoring of the Runx1 IHC staining of the human breast cancer tissue microarray (mag. 20x).

Supplementary Material Fig. S3. Runx1 RNA expression in a cohort of normal and invasive breast cancer tissue samples. RNA expression values were obtained from the Gluck et al microarray data and analyzed for Runx1 expression in the 4 normal and 154 invasive breast cancer patient tissue samples. The dotted red line indicates the average expression in the normal breast tissue samples, highlighting that 72% of invasive breast cancer samples expressed increased Runx1 as compared with controls. Graph shown is a modified version of what is available for the Gluck dataset at www.oncomine.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of our laboratories as well as our collaborators, especially Dana Frederick, Phillip Tai, Jason Dobson, Justine Landis and Jennifer Colby for technical assistance with experimentation, critical comments, advice, and/or general support. We also thank Joseph R Boyd for valuable input and expertise on statistical analysis of immunohistochemical analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Vermont Cancer Center and Lake Champlain Cancer Research Organization (GB); EMBO and Humboldt Foundation (HT); National Institutes of Health NCI P01 CA082834 (GSS, JLS, JBL) and Pfizer IIR WS2049100 (GSS, JBL).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- BANERJI S, CIBULSKIS K, RANGEL-ESCARENO C, BROWN KK, CARTER SL, FREDERICK AM, LAWRENCE MS, SIVACHENKO AY, SOUGNEZ C, ZOU L, CORTES ML, FERNANDEZ-LOPEZ JC, PENG S, ARDLIE KG, AUCLAIR D, BAUTISTA-PINA V, DUKE F, FRANCIS J, JUNG J, MAFFUZ-AZIZ A, ONOFRIO RC, PARKIN M, PHO NH, QUINTANAR-JURADO V, RAMOS AH, REBOLLAR-VEGA R, RODRIGUEZ-CUEVAS S, ROMERO-CORDOBA SL, SCHUMACHER SE, STRANSKY N, THOMPSON KM, URIBE-FIGUEROA L, BASELGA J, BEROUKHIM R, POLYAK K, SGROI DC, RICHARDSON AL, JIMENEZ-SANCHEZ G, LANDER ES, GABRIEL SB, GARRAWAY LA, GOLUB TR, MELENDEZ-ZAJGLA J, TOKER A, GETZ G, HIDALGO-MIRANDA A, MEYERSON M. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature. 2012;486:405–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLYTH K, CAMERON ER, NEIL JC. The RUNX genes: gain or loss of function in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:376–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUESA RJ. Quantifying quality: A review and scale proposal. J Histotechnol. 2005;28:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- CAMERON ER, NEIL JC. The Runx genes: lineage-specific oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Oncogene. 2004;23:4308–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANCER GENOME ATLAS NETWORK. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEON DJ, ORSULIC S. Mouse models of cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:95–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.3.121806.154244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIMGE NO, BANIWAL SK, LUO J, COETZEE S, KHALID O, BERMAN BP, TRIPATHY D, ELLIS MJ, FRENKEL B. Opposing effects of Runx2 and estradiol on breast cancer cell proliferation: in vitro identification of reciprocally regulated gene signature related to clinical letrozole responsiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:901–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIMGE NO, FRENKEL B. The RUNX family in breast cancer: relationships with estrogen signaling. Oncogene. 2013;32:2121–30. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUANG LS, ITO K, ITO Y. RUNX family: Regulation and diversification of roles through interacting proteins. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1260–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNNINGHAM L, FINCKBEINER S, HYDE RK, SOUTHALL N, MARUGAN J, YEDAVALLI VR, DEHDASHTI SJ, REINHOLD WC, ALEMU L, ZHAO L, YEH JR, SOOD R, POMMIER Y, AUSTIN CP, JEANG KT, ZHENG W, LIU P. Identification of benzodiazepine Ro5-3335 as an inhibitor of CBF leukemia through quantitative high throughput screen against RUNX1-CBFbeta interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14592–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200037109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLL A, GONZALEZ M, ABAL M, LLAURADO M, RIGAU M, COLAS E, MONGE M, XERCAVINS J, CAPELLA G, DIAZ B, GIL-MORENO A, ALAMEDA F, REVENTOS J. An orthotopic endometrial cancer mouse model demonstrates a role for RUNX1 in distant metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:257–63. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIS MJ, DING L, SHEN D, LUO J, SUMAN VJ, WALLIS JW, VAN TINE BA, HOOG J, GOIFFON RJ, GOLDSTEIN TC, NG S, LIN L, CROWDER R, SNIDER J, BALLMAN K, WEBER J, CHEN K, KOBOLDT DC, KANDOTH C, SCHIERDING WS, MCMICHAEL JF, MILLER CA, LU C, HARRIS CC, MCLELLAN MD, WENDL MC, DESCHRYVER K, ALLRED DC, ESSERMAN L, UNZEITIG G, MARGENTHALER J, BABIERA GV, MARCOM PK, GUENTHER JM, LEITCH M, HUNT K, OLSON J, TAO Y, MAHER CA, FULTON LL, FULTON RS, HARRISON M, OBERKFELL B, DU F, DEMETER R, VICKERY TL, ELHAMMALI A, PIWNICA-WORMS H, MCDONALD S, WATSON M, DOOLING DJ, OTA D, CHANG LW, BOSE R, LEY TJ, PIWNICA-WORMS D, STUART JM, WILSON RK, MARDIS ER. Whole-genome analysis informs breast cancer response to aromatase inhibition. Nature. 2012;486:353–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRARI N, MOHAMMED ZM, NIXON C, MASON SM, MALLON E, MCMILLAN DC, MORRIS JS, CAMERON ER, EDWARDS J, BLYTH K. Expression of RUNX1 Correlates with Poor Patient Prognosis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER AH, JACOBSON KA, ROSE J, ZELLER R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4986. pdb prot4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCI C, ZHOU J, JIANG Z, MODRUSAN Z, GOOD Z, JACKSON E, KOUROS-MEHR H. Biomarkers of residual disease, disseminated tumor cells, and metastases in the MMTV-PyMT breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEDMAN AD. Cell cycle and developmental control of hematopoiesis by Runx1. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:520–4. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLUCK S, ROSS JS, ROYCE M, MCKENNA EF, JR, PEROU CM, AVISAR E, WU L. TP53 genomics predict higher clinical and pathologic tumor response in operable early-stage breast cancer treated with docetaxel-capecitabine +/− trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:781–91. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUY CT, CARDIFF RD, MULLER WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:954–61. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERSCHKOWITZ JI, SIMIN K, WEIGMAN VJ, MIKAELIAN I, USARY J, HU Z, RASMUSSEN KE, JONES LP, ASSEFNIA S, CHANDRASEKHARAN S, BACKLUND MG, YIN Y, KHRAMTSOV AI, BASTEIN R, QUACKENBUSH J, GLAZER RI, BROWN PH, GREEN JE, KOPELOVICH L, FURTH PA, PALAZZO JP, OLOPADE OI, BERNARD PS, CHURCHILL GA, VAN DYKE T, PEROU CM. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICHIKAWA M, YOSHIMI A, NAKAGAWA M, NISHIMOTO N, WATANABE-OKOCHI N, KUROKAWA M. A role for RUNX1 in hematopoiesis and myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2013;97:726–34. doi: 10.1007/s12185-013-1347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO Y. Oncogenic potential of the RUNX gene family: ‘overview’. Oncogene. 2004;23:4198–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANES KA. RUNX1 and its understudied role in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3461–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.20.18029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEMAL A, BRAY F, CENTER MM, FERLAY J, WARD E, FORMAN D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KADOTA M, YANG HH, GOMEZ B, SATO M, CLIFFORD RJ, MEERZAMAN D, DUNN BK, WAKEFIELD LM, LEE MP. Delineating genetic alterations for tumor progression in the MCF10A series of breast cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEITA M, BACHVAROVA M, MORIN C, PLANTE M, GREGOIRE J, RENAUD MC, SEBASTIANELLI A, TRINH XB, BACHVAROV D. The RUNX1 transcription factor is expressed in serous epithelial ovarian carcinoma and contributes to cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:972–86. doi: 10.4161/cc.23963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOUROS-MEHR H, BECHIS SK, SLORACH EM, LITTLEPAGE LE, EGEBLAD M, EWALD AJ, PAI SY, HO IC, WERB Z. GATA-3 links tumor differentiation and dissemination in a luminal breast cancer model. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMBERT AW, OZTURK S, THIAGALINGAM S. Integrin signaling in mammary epithelial cells and breast cancer. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:493283. doi: 10.5402/2012/493283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANGLEY RR, FIDLER IJ. Tumor cell-organ microenvironment interactions in the pathogenesis of cancer metastasis. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:297–321. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN EY, JONES JG, LI P, ZHU L, WHITNEY KD, MULLER WJ, POLLARD JW. Progression to malignancy in the polyoma middle T oncoprotein mouse breast cancer model provides a reliable model for human diseases. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2113–26. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDONALD L, FERRARI N, TERRY A, BELL M, MOHAMMED ZM, ORANGE C, JENKINS A, MULLER WJ, GUSTERSON BA, NEIL JC, EDWARDS J, MORRIS JS, CAMERON ER, BLYTH K. RUNX2 correlates with subtype-specific breast cancer in a human tissue microarray, and ectopic expression of Runx2 perturbs differentiation in the mouse mammary gland. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:525–34. doi: 10.1242/dmm.015040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIKHAIL FM, SINHA KK, SAUNTHARARAJAH Y, NUCIFORA G. Normal and transforming functions of RUNX1: a perspective. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:582–93. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGLE JA, MA Z, BYRNE MA, WHITE MF, SHAW LM. Involvement of insulin receptor substrate 2 in mammary tumor metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9726–35. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9726-9735.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OWENS RB, SMITH HS, HACKETT AJ. Epithelial cell cultures from normal glandular tissue of mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;53:261–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEROU CM, SORLIE T, EISEN MB, VAN DE RIJN M, JEFFREY SS, REES CA, POLLACK JR, ROSS DT, JOHNSEN H, AKSLEN LA, FLUGE O, PERGAMENSCHIKOV A, WILLIAMS C, ZHU SX, LONNING PE, BORRESEN-DALE AL, BROWN PO, BOTSTEIN D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLANAGUMA J, DIAZ-FUERTES M, GIL-MORENO A, ABAL M, MONGE M, GARCIA A, BARO T, THOMSON TM, XERCAVINS J, ALAMEDA F, REVENTOS J. A differential gene expression profile reveals overexpression of RUNX1/AML1 in invasive endometrioid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8846–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATAP J, IMBALZANO KM, UNDERWOOD JM, COHET N, GOKUL K, AKECH J, VAN WIJNEN AJ, STEIN JL, IMBALZANO AN, NICKERSON JA, LIAN JB, STEIN GS. Ectopic runx2 expression in mammary epithelial cells disrupts formation of normal acini structure: implications for breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6807–14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATAP J, JAVED A, LANGUINO LR, VAN WIJNEN AJ, STEIN JL, STEIN GS, LIAN JB. The Runx2 osteogenic transcription factor regulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 in bone metastatic cancer cells and controls cell invasion. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8581–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8581-8591.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATAP J, LIAN JB, JAVED A, BARNES GL, VAN WIJNEN AJ, STEIN JL, STEIN GS. Regulatory roles of Runx2 in metastatic tumor and cancer cell interactions with bone. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:589–600. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATAP J, LIAN JB, STEIN GS. Metastatic bone disease: role of transcription factors and future targets. Bone. 2011;48:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODRIGUEZ-VICIANA P, COLLINS C, FRIED M. Polyoma and SV40 proteins differentially regulate PP2A to activate distinct cellular signaling pathways involved in growth control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609343103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEITZ CJ, LEE TS, MCDERMITT DJ, TUMBAR T. Defining a tissue stem cell-driven Runx1/Stat3 signalling axis in epithelial cancer. EMBO J. 2012;31:4124–39. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPECK NA, TERRYL S. A new transcription factor family associated with human leukemias. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1995;5:337–64. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v5.i3-4.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIUCHI I, OSATO M, ITO Y. Runx1: no longer just for leukemia. EMBO J. 2012;31:4098–9. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN BRAGT MP, HU X, XIE Y, LI Z. RUNX1, a transcription factor mutated in breast cancer, controls the fate of ER-positive mammary luminal cells. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAQUERIZAS JM, KUMMERFELD SK, TEICHMANN SA, LUSCOMBE NM. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:252–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOTTON S, STEWART M, BLYTH K, VAILLANT F, KILBEY A, NEIL JC, CAMERON ER. Proviral insertion indicates a dominant oncogenic role for Runx1/AML-1 in T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7181–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHU M, YI M, KIM CH, DENG C, LI Y, MEDINA D, STEPHENS RM, GREEN JE. Integrated miRNA and mRNA expression profiling of mouse mammary tumor models identifies miRNA signatures associated with mammary tumor lineage. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R77. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material Fig. S1. Runx1 IHC controls, antibody validation and reference image panels used for blind scoring and semi-quantitative assessment of mouse tissues. (A) The Runx1 antibody used for western blotting and IHC in both human and mouse tissue was validated to confirm is specificity in a number of ways: To confirm that the Runx1 antibody did not cross react with Runx2, another Runx protein family member, sequential sections from the mammary gland of an MMTV-PyMT mouse were stained with an antibody against Runx2 (rabbit polyclonal (M70) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) alongside the Runx1 antibody (left panel). As shown, the two antibodies stained distinctly different cells in the mammary gland: Luminal epithelial cells (denoted by a black L) were Runx1 positive and Runx2 negative, whereas myoepithelial cells (denoted by a black M) were Runx1 negative and Runx2 positive. Prostate tissue (known to express Runx2) was assessed for Runx1 and Runx2 expression (middle panel). Prostate epithelial cells expressed strong nuclear Runx2, whereas only weak staining of a small number of the same cells was seen for Runx1. Western blotting for Runx1 and Runx2 was performed in two independent whole cell lysate samples from NMuMG and MMTV mouse mammary gland cells (right panel, top). Distinctive expression patterns for both proteins were evident: NMuMG cells express high levels of Runx2 and very little Runx1 yet MMTV cells express high levels of Runx1 and very little (if any) Runx2. Human mammary adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (MCF7) either untransfected (Mock) or transfected with two different quantities of empty vector control (+Vector) or RUNX1 overexpression vector (+Runx1) were used as an independent validation (right panel, bottom). The same protocols used for IHC and western blotting using the Runx1 antibody were used for the Runx2 antibody (See Materials and Methods). Scale bar = 200μm. (B) Representative images of one positive tissue control and two negative reagent controls processed with each Runx1 IHC staining procedure demonstrating an optimized staining protocol, allowing for confidence in the accurate interpretation of results. Scale bar = 200μm. (C) Reference image panels used for blind scoring of the Runx1 IHC staining of the tissue samples from the MMTV-PyMT mouse model. Given that background staining in each tissue differed, a new panel of images representative of each score for each tissue was used to more accurately reflect changes in Runx1 expression in individual tissues. Scale bars = 500μm; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; DAB: 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine.

Supplementary Material Fig. S2. Reference image panels used for blind scoring of the Runx1 IHC staining of the human breast cancer tissue microarray (mag. 20x).

Supplementary Material Fig. S3. Runx1 RNA expression in a cohort of normal and invasive breast cancer tissue samples. RNA expression values were obtained from the Gluck et al microarray data and analyzed for Runx1 expression in the 4 normal and 154 invasive breast cancer patient tissue samples. The dotted red line indicates the average expression in the normal breast tissue samples, highlighting that 72% of invasive breast cancer samples expressed increased Runx1 as compared with controls. Graph shown is a modified version of what is available for the Gluck dataset at www.oncomine.org.