Spermatogenesis is a complex process through which male germ-line stem cells proliferate and differentiate, eventually becoming spermatozoa. Successful spermatogenesis requires precise regulation of gene expression at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational and post-translational levels. Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification known to control protein turnover and, thus, plays a critical role in numerous biological processes, including spermatogenesis (Hou et al., 2012). The ubiquilin family consists of five ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubqln1-4 and Ubqlnl), all of which contain an N-terminal UBL domain and a C-terminal ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain (Hou et al., 2012).

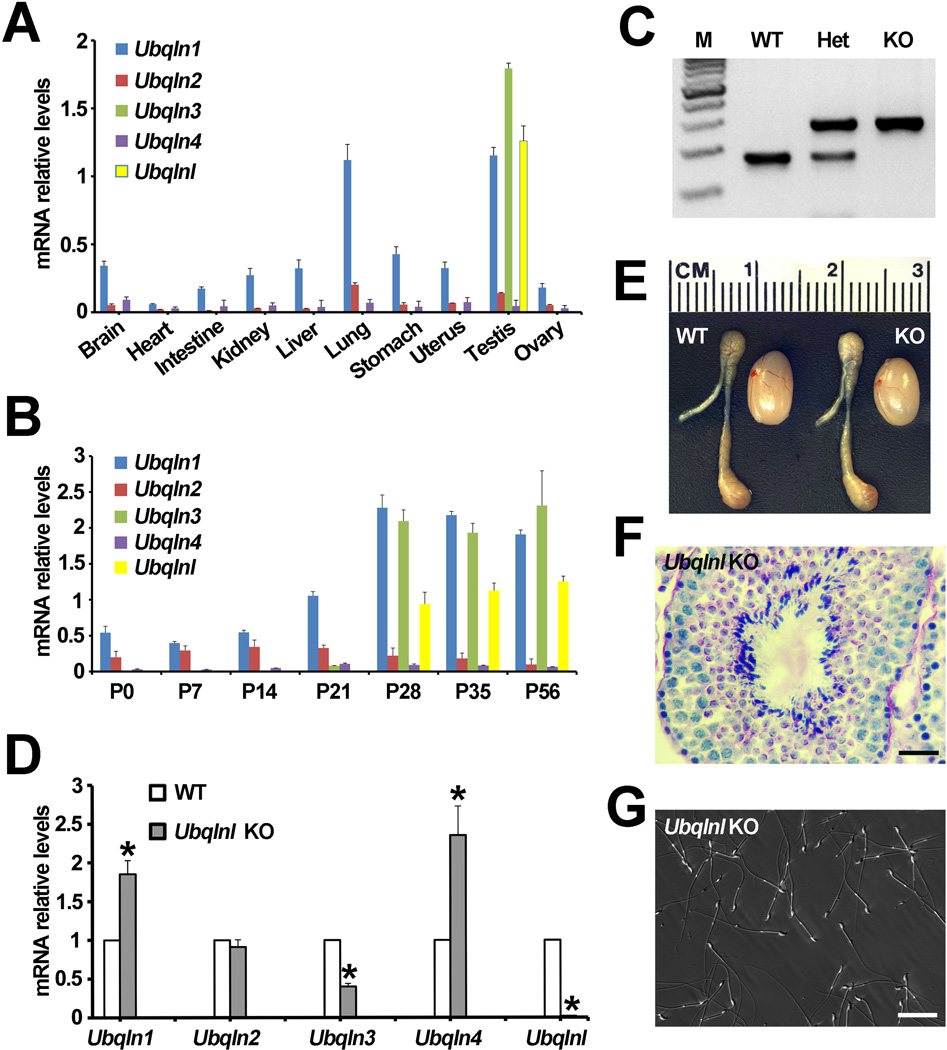

We previously demonstrated that Ubqln3 is exclusively expressed in the testis, yet ablation of Ubqln3 causes no discernable phenotype, suggesting it has a dispensable role in mouse spermatogenesis (Yuan S, 2015). We subsequently discovered that another member of the ubiquilin gene family, Ubqlnl, is only ~5 kb apart from Ubqln3 on mouse chromosome 7. Of 10 different mouse organs assessed using quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (qPCR), we found that, similar to Ubqln3, Ubqlnl was exclusively detected in the testis (Fig. 1A). Ubqlnl transcript was first detected in the testes by postnatal day 28 (P28) and plateaued in adults (P56) (Fig. 1B). The timing of Ubqlnl expression onset at ~P28 suggests that it is mainly expressed in elongating/elongated spermatids, which is a pattern similar to that of Ubqln3 (Yuan S, 2015).

Figure 1.

Ubqlnl is a testis-specific gene dispensable for spermatogenesis. A: qPCR analyses of expression levels of five ubiquilin genes (Ubqln1-4 and Ubqlnl) in 10 organs of adult mice. B: Expression levels of five ubiquilin genes in developing testes, based on qPCR analysis, from mouse testes at postnatal day 0 (P0, newborn), P7, P14, P21, P28, P35, and P56. C: A representative genotyping PCR result. M, MW marker; WT, wild-type; Het, heterozygous; KO, knockout. D: qPCR assays of mRNA levels of five ubiquilin genes in Ubqlnl-KO testes. *P < 0.05 compared to WT, n=3 (Student’s t-test). E: Similar gross morphology of WT and Ubqlnl-KO testes. One unit on the ruler is 1mm. F: A representative image of Periodic acid-Schiff-stained Ubqlnl KO testes section. Scale bar, 50 µm. G: A representative phase-contrast micrograph showing normal morphology of Ubqlnl-KO sperm. Scale bar, 50µm.

To study the physiological role of Ubqlnl, we generated Ubqlnl global knockout (KO) mice using cryopreserved sperm carrying a null Ubqlnl allele (allele information: Ubqlnl_A06, C57Bl/6N-Ubqlnltm1(KOMP)Vlcg) that is available from the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) repository. The Ubqlnl-null allele was generated using the “gene trap” strategy, in which a gene-trap cassette (ZEN-UB1) was inserted into the Ubqlnl locus (KOMP project ID: VG11289). Genotyping analyses demonstrated that Ubqlnl KO mice were homozygous for Ubqlnl-null alleles (Fig. 1C), and qPCR analyses confirmed the absence of Ubqlnl expression in the testes of KO males (Fig. 1D). Both female and male Ubqlnl-KO mice were viable, and did not exhibit discernable differences in either growth or behavior compared to their wild-type (WT) or heterozygous littermates.

A 5-month-long fecundity test using Ubqlnl-KO males bred with WT females of proven fertility revealed no significant difference in either litter size (7.7 ± 1.2 for WT and 7.3 ± 1.1 for KO, n=6, P > 0.05; t-test) or litter interval (22.8 ± 2.8 for WT and 23.3 ± 2.2 for KO, n=6, P > 0.05; t-test) compared to WT breeding pairs, suggesting that Ubqlnl KO males are fertile. Consistent with their normal fertility, testis size and weight of adult Ubqlnl KO males were similar to those of WT males (Fig. 1E), and Ubqlnl KO males displayed normal testicular histology with robust spermatogenesis (Fig. 1F) and normal sperm morphology (Fig.1G). Taken together, our data suggest that, despite its testis-exclusive expression, Ubqlnl is not required for spermatogenesis or fertility in male mice.

We also analyzed transcripts levels of the other four ubiquilin genes (Marin, 2014), in WT and Ubqlnl-KO testes using qPCR. Interestingly, levels of Ubqln1 and Ubqln4 mRNAs were significantly increased in Ubqlnl-KO compared to WT testes (Fig. 1D). This suggests that other ubiquilin family members may have compensated for the loss of Ubqlnl, thus maintaining a normal phenotype in Ubqlnl-KO males. Together, these findings demonstrate that Ubqlnl is dispensable for both embryonic and postnatal development and for spermatogenesis in mice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HD060858, HD071736, and HD074573 (to W.Y.).

REFERENCES

- Hou X, Zhang W, Xiao Z, Gan H, Lin X, Liao S, Han C. Mining and characterization of ubiquitin E3 ligases expressed in the mouse testis. BMC genomics. 2012;13:495. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin I. The ubiquilin gene family: evolutionary patterns and functional insights. BMC evolutionary biology. 2014;14:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Qin W, Riordan CR, Mcswiggin H, Zheng H, Yan W. Ubqln3, a testis-specific gene, is dispensable for embryonic development and spermatogenesis in mice. Molecular reproduction and development. 2015;82(4):266–267. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]