Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to improve patient understanding of surgical outcomes while they make a preference-sensitive decision regarding electing endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Study Design

Prospective observational cohort study

Methods

Patients with CRS who elected ESS were prospectively enrolled into a multi-institutional, observational cohort study. Patients’ were categorized into 10 preoperative SNOT-22 groupings based on 10-point increments beginning at a score of 10 and ending at 110. The proportion of patients achieving a SNOT-22 MCID (9 points) and the percentage of relative improvement (%) for each preoperative SNOT-22 group were calculated. A subgroup analysis based on polyp status was performed.

Results

A total of 327 patients were included in this study. Patients with a SNOT-22 score between 10-19 had the lowest chance of achieving an MCID (37.5%) and received a relative mean worsening of their QoL after ESS (+18.8%). Patients with a SNOT-22 score greater than 30 obtained a greater than 75% chance of achieving an MCID and there was a relative improvement of 45% in QoL (all < −44.9%) after ESS. Outcomes from the polyp status subgroup analysis were similar to the findings from the overall cohort.

Conclusion

Outcomes from this study suggest that patients with a preoperative SNOT-22 score higher than 30 points receive a greater than 75% chance of achieving an MCID and on average obtain a 45% relative improvement in their QoL after ESS. Patients with SNOT-22 score of less than 20 did not experience improved QoL from ESS.

Keywords: Endoscopic sinus surgery, chronic rhinosinusitis, sinusitis, SNOT-22, shared decision making, quality of life

Introduction

Preference-sensitive care involves trade-offs between the patients potential benefit, risk, and cost when making treatment decisions1. Ideally, both the patient and physician would possess all information for a specific intervention’s outcome, thus decisions would be made based on a complete understanding of the benefits, risks, and cost. Unfortunately, the reality is that patients function in health systems with incomplete understanding of outcomes, thus practice patterns may be potentially driven by physician opinion rather than informed patient choice and preference. This can lead to undesired practice variation and reduce the overall performance of a health care system. Therefore, it is important to improve the patient’s understanding of potential outcomes from an intervention in order to provide them with essential information necessary to make an informed and rationale decision.

Management of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) involves preference-sensitive care since patients are commonly faced with treatment decisions which involve multiple domains of benefit, risk, and cost, such as quality of life (QoL), productivity, monetary expenses, and adverse events. Specifically, patients with refractory CRS often encounter the decision to either continue with medical therapy or elect to undergo endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). Without adequate information on patient-specific outcomes, the decision to pursue surgery can be challenging for patients which is then often deferred to the physician’s opinion rather than reflecting the patient’s true preference. In order to continue improving the quality of care for patients with CRS, it is important to improve the information on intervention-specific outcomes in order to help patients make informed preference-based decisions.

Given that symptom severity and patient QoL are major drivers in the decision for ESS2,3, the objective of this study was to evaluate the proportion of patients receiving a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) after ESS based on their preoperative QoL level4. The purpose of this study is to improve the shared-decision making process by improving patient understanding of their QoL outcomes after ESS. Our primary outcomes were: 1) the chance of receiving an MCID improvement of a 9-points in the 22-item Sinonasal Outcomes Test (SNOT-22) after ESS for different preoperative QoL levels, and 2) the percentage of relative improvement in SNOT-22 after ESS for different preoperative QoL levels.

Methods

i. General

Data for this study was obtained from a prospectively collected database developed for a National Institute of Health-funded trial comparing the surgical and medical management in patients with CRS (Clinicaltrials# NCT01332136). As of Sept 2014, there were 551 patients who received ESS. Inclusion criteria includes adults (age > 18 years old), diagnosis of CRS based on American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Adult Sinusitis guidelines5, and refractory status as defined by persistent sinonasal symptoms despite a minimum of 3 months topical corticosteroid therapy, minimum 7 day course of system corticosteroid, and 2 weeks of a broad-spectrum systemic antibiotic. Exclusion criteria included patients without a minimum of 6 months follow-up after ESS, patients who elected to continue with medical therapy as opposed to receiving sinus surgery, systemic granulomatous disease, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis, cystic fibrosis, and ciliary dyskinesia. Due to preoperative survey floor effects, patients with a preoperative SNOT-22 score between 0 and 9 were also excluded since they were unable to achieve a MCID of 9 points.

ii. Defined Preoperative SNOT-22 Levels

The first analysis considered the entire CRS cohort as one single entity. Next, to increase the homogeneity of the patient cohorts, patients were categorized into two groups based on polyp status (CRSsNP, CRS without nasal polyposis; and CRSwNP, CRS with nasal polyposis). A concurrent septoplasty during ESS has not been shown to be a confounding variable on CRS-related Qol outcomes, therefore we have not performed a subgroup analysis based on receiving a concurrent septoplasty6.

Every patient included in this study received a preoperative (i.e. baseline) and postoperative SNOT-22 score. Postoperative SNOT-22 scores were measured at 6 and 12 months after ESS. The longest available follow-up SNOT-22 score per patient after ESS was used for calculating the mean postoperative scores for each group. The SNOT-22 is a validated 22-item CRS-specific QoL instrument which is scored using a Likert scale where 0=”No problem”, 1=”Very mild problem”, 2=”Mild or slight problem”, 3=”Moderate problem”, 4=”Severe problem”, and 5=”Problem as bad as it can be”4. Higher scores on the SNOT-22 survey items suggest worse patient functioning or symptom severity (total score range: 0-110).

The proportion of patients achieving an MCID after ESS were evaluated by categorizing patients into 10 preoperative SNOT-22 groupings based on 10-point increments beginning at 10 and ending at 110. Patient demographics and comorbidities were compared across preoperative levels of SNOT-22 using Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) testing with 2×10 contingency tables and the ANOVA/Kruskall-Wallis test for continuous variables. The reported significant p-value is from each ‘global’ test and indicates a significant difference in demographic or comorbidity between at least 2 of the SNOT-22 groupings.

iii. Patient Outcomes Categorized Using Preoperative SNOT-22 Scores

The proportion of patients achieving an MCID of at least a 9-point improvement on the SNOT-22 is reported for each preoperative SNOT-22 group4. The percentage of relative improvement for each preoperative SNOT-22 group was also calculated using the formula: [(mean postoperative score) − (mean preoperative score) / mean preoperative score] × 1007. Larger negative percentages of relative improvement indicate larger postoperative improvements compared to the patient’s preoperative SNOT-22 score.

Results

i. Cohort Demographics

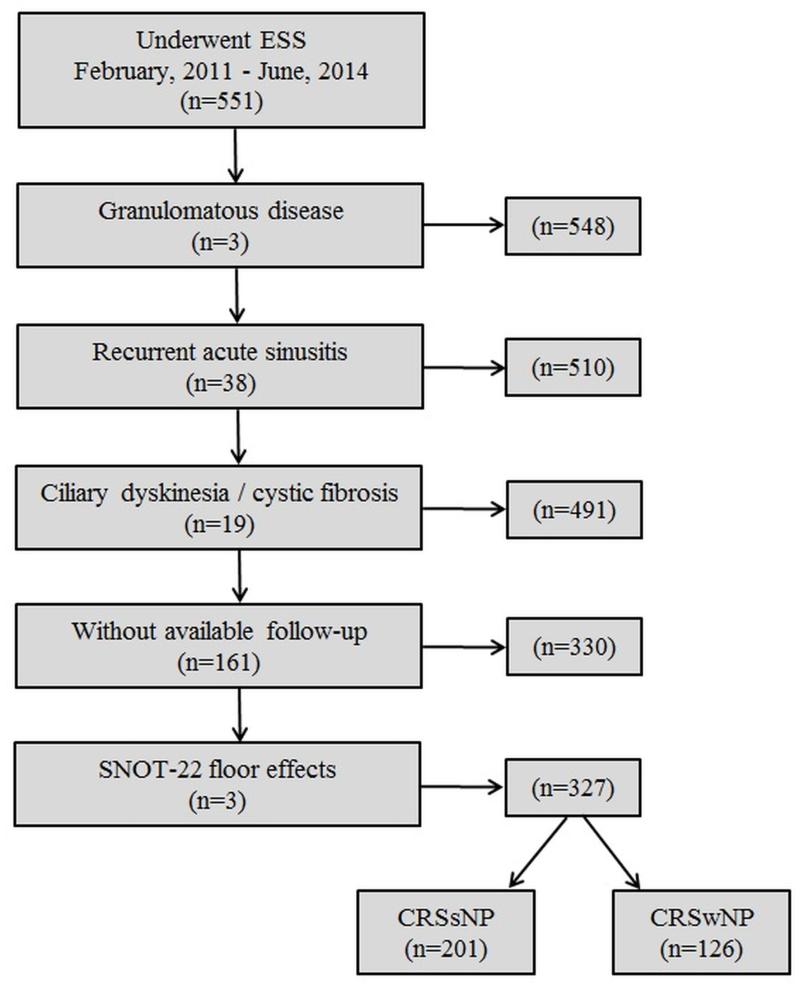

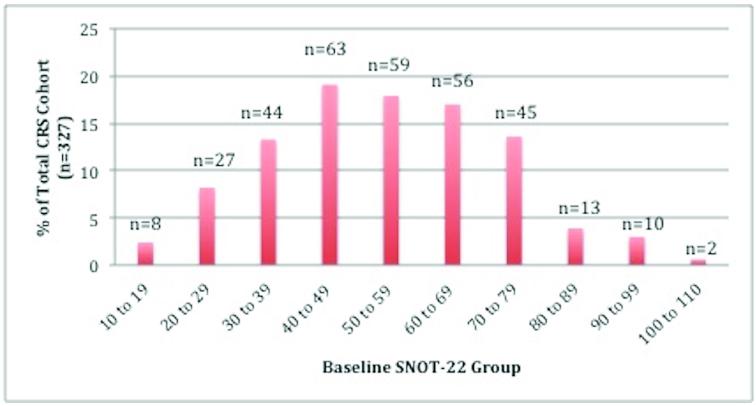

A total of 327 patients with refractory CRS who elected ESS were included in this study; CRSsNP=201 and CRSwNP=126 (Figure 1). Mean follow-up for the overall cohort was 14.0 months (SD 5.1; range 6-23 months). The sample sizes for each preoperative SNOT-22 group appeared to follow a normal distribution, with the largest groups composed of patients with SNOT-22 scores between 40 and 70 (Figure 2). The overall CRS patient demographics as well as CRS-specific comorbidities were compared for each preoperative SNOT-22 group and a p-value < 0.05 indicates that there was a statistically significant difference between two preoperative SNOT-22 groups (Table 1). There was higher proportion of females and depression present in the SNOT-22 groups with scores between 40 to 80, p=0.035 and 0.028, respectively. Endoscopy scores increased as SNOT-22 score grouping increased (p=0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of overall CRS cohort

Figure 2.

Distribution of overall sample sizes for each preoperative SNOT-22 group

Table 1.

Demographics for the overall CRS cohort based on their preoperative SNOT-22 grouping

| Preoperative SNOT-22 Grouping | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall CRS cohort (n=327) |

10-19 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | 80-89 | 90-99 | 100- 110 |

p-value |

| Number of Patients in Group (%) |

8 (2.4) | 27 (8.3) |

44 (13.5) |

63 (19.3) |

59 (18.0) |

56 (17.1) |

45 (13.8) |

13 (4.0) | 10 (3.1) | 2 (0.6) | ---- |

| Mean follow-up months [SD] |

13.4 [7.3] |

15.2 [5.8] |

13.1 [5.6] |

14.4 [5.7] |

14.7 [4.6] |

13.8 [5.5] |

15.3 [5.6] |

15.0 [5.3] |

14.1 [6.3] |

11.5 [7.8] |

0.731 |

| Mean Age [SD] | 59.4 [13.0] |

54.2 [17.45] |

54.6 [16.6] |

51.8 [15.1] |

51.1 [14.6] |

53.9 [13.7] |

46.8 [15.2] |

55.0 [14.3] |

54.1 [15.4] |

44.0 [22.6] |

0.261 |

| Number of Females (%) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (29.6) | 22 (50.0) |

28 (44.4) |

33 (55.9) |

32 (57.1) |

31 (68.9) |

6 (46.2) | 8 (80.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0.035 |

| Number with Asthma (%) |

3 (37.5) | 7 (25.9) | 10 (22.7) |

18 (28.6) |

26 (44.1) |

25 (44.6) |

19 (42.2) |

7 (53.8) | 5 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0.066 |

| Number with Allergy (%) |

3 (37.5) | 8 (29.6) | 17 (38.6) |

19 (30.2) |

27 (45.8) |

29 (51.8) |

21 (46.7) |

3 (23.1) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0.157 |

| Number with Depression (%) |

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 12 (19.0) |

13 (22.0) |

12 (21.4) |

12 (26.7) |

1 (7.7) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.028 |

| Mean CT Score [SD] | 8.6 [4.6] |

12.1 [6.8] |

12.6 [5.4] |

11.3 [6.2] |

12.1 [6.3] |

13.4 [6.5] |

12.6 [5.8] |

16.2 [5.8] |

14.5 [5.6] |

18.5 [2.1] |

0.068 |

| Mean Endoscopy Score [SD] |

3.8 [3.1] |

5.2 [3.4] |

6.2 [3.7] |

4.9 [3.9] |

6.9 [3.7] |

7.0 [4.1] |

6.9 [3.7] |

7.6 [4.4] |

8.7 [3.5] |

10.0 [1.4] |

0.001 |

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; SD, standard deviation; CT, computed tomography

ii. Overall CRS Cohort Outcomes per Preoperative SNOT-22 Group

When considering the CRS cohort as one single entity, 80% achieved an MCID improvement of 9 points after ESS and patients received an average of 46.4% improvement in their preoperative SNOT-22 scores. When evaluating the overall cohort based on their preoperative SNOT-22 score grouping, patients with preoperative SNOT-22 scores between 10-19 and 20-29 had the lowest chance of achieving an MCID improvement after ESS, 37.5% and 55.6%, respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, patients with a preoperative SNOT-22 score between 10-19 received an average increase of their score by +18.8% (indicating worsening QoL) as compared to all other groups which received average reductions in their SNOT-22 scores (all relative improvements of more than −36.1%; indicating improvements). Using the total cohort, there is a significant difference in the frequency of achieving at least one MCID across preoperative SNOT-22 groupings (χ2=26.54; p=0.002).

Table 2.

Probability of a patient with CRS (with or without polyps) achieving an MCID after ESS based on their preoperative SNOT-22 score grouping

| Preoperative SNOT-22 Grouping |

Probability of achieving an MCID after ESS |

Relative improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (n=8) | 3 (37.5%) | +18.8% |

| 20-29 (n=27) | 15 (55.6%) | −36.1% |

| 30-39 (n=44) | 33 (75.0%) | −47.2% |

| 40-49 (n=63) | 52 (82.5%) | −45.0% |

| 50-59 (n=59) | 49 (83.1%) | −48.6% |

| 60-69 (n=56) | 49 (87.5%) | −49.5% |

| 70-79 (n=45) | 41 (91.1%) | −48.3% |

| 80-89 (n=13) | 10 (76.9%) | −44.9% |

| 90-99 (n=10) | 8 (80.0%) | −34.6% |

| 100-109 (n=2) | 2 (100.0%) | −69.1% |

| OVERALL | 262 (80.1%) | −46.4% |

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; MCID, minimal clinically important difference

iii. CRSsNP and CRSwNP Subgroup Analysis

For the CRSsNP cohort, patients with scores between 10-19 and 20-29 had the lowest chance of achieving an MCID of 9 points after ESS, 50% and 56.3%, respectively (Table 3). Similarly, for the CRSwNP cohort, patients with SNOT-22 scores between 10-19 and 20-29 had the lowest chance of achieving an MCID of 9 points after ESS, 0% and 54%, respectively (Table 4). When evaluating the relative improvement of SNOT-22 score after ESS, on average patients with a SNOT-22 score between 10-19, in both the CRSsNP and CRSwNP cohorts, received a worse SNOT-22 outcome with a relative increase of preoperative SNOT-22 score of +14.8% and +34.6%, respectively (Table 3 and 4). Based on the SNOT-22 groupings for CRSsNP and CRSwNP, patients with SNOT-22 scores greater than 30 demonstrate a greater than 80% chance of achieving an MCID improvement of 9 points. The only exception was a 71.4% and 66.7% chance of achieving an MCID improvement in CRSsNP patients with SNOT-22 scores between 80-89 and 90-99 (Table 3). For CRSsNP, there was no significant difference in the frequency of MCID improvement across preoperative SNOT-22 score groupings (χ2=12.88; p=0.168). For CRSwNP, there is a significant difference in the frequency of achieving at least one MCID across preoperative SNOT-22 groupings (χ2=18.63; p=0.029).

Table 3.

Probability of CRSsNP patients achieving an MCID after ESS based on their preoperative SNOT-22 score grouping

| Preoperative SNOT-22 Grouping |

Probability of CRSsNP patients achieving an MCID after ESS |

Relative improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (n=6) | 3 (50.0%) | +14.8% |

| 20-29 (n=16) | 9 (56.3%) | −45.6% |

| 30-39 (n=28) | 20 (71.4%) | −48.4% |

| 40-49 (n=42) | 35 (83.3%) | −40.1% |

| 50-59 (n=35) | 28 (80.0%) | −46.6% |

| 60-69 (n=34) | 29 (85.3%) | −49.6% |

| 70-79 (n=29) | 26 (89.7%) | −46.9% |

| 80-89 (n=7) | 5 (71.4%) | −45.8% |

| 90-99 (n=3) | 2 (66.7%) | −34.6% |

| 100-109 (n=1) | 1 (100.0%) | −49.5% |

CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; MCID, minimal clinically important difference

Table 4.

Probability of CRSwNP patients achieving an MCID after ESS based on their preoperative SNOT-22 score grouping

| Preoperative SNOT-22 Grouping |

Probability of CRSwNP patients achieving an MCID after ESS |

Relative improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10-19 (n=2) | 0 (0.0%) | +34.6% |

| 20-29 (n=11) | 6 (54.5%) | −22.0% |

| 30-39 (n=16) | 13 (81.3%) | −45.3% |

| 40-49 (n=21) | 17 (81.0%) | −53.6% |

| 50-59 (n=24) | 21 (87.5%) | −51.4% |

| 60-69 (n=22) | 20 (90.9%) | −49.5% |

| 70-79 (n=16) | 15 (93.8%) | −50.7% |

| 80-89 (n=6) | 5 (83.3%) | −44.0% |

| 90-99 (n=7) | 6 (85.7%) | −34.6% |

| 100-109 (n=1) | 1 (100.0%) | −87.7% |

CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; MCID, minimal clinically important difference

Discussion

Based on prior research, a patients’ decision to elect ESS for medically refractory CRS is primarily driven by the degree of their preoperative QoL impairment2. Furthermore, preoperative QoL is an important metric to predict outcomes following either continued medical therapy or ESS8-10. Prior work using other patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) have demonstrated that after ESS patients improve an average of 15.8% on the rhinosinusitis disability index (RSDI) and 21% on the chronic sinusitis survey (CSS), while 71% and 76% of patients experienced an MCID using these metrics11. The results from the RSDI and CSS-based study were analyzed after eliminating the least symptomatic quintile. The only clinical factor which predicted likelihood of improvement was primary revision surgery status. Using the SNOT-22 instrument, our results demonstrate that overall, patients improve by an average of 46%, and similar to prior studies, 70%-80% achieve an MCID improvement.

This study has further refined the findings from prior studies by now being able to predict the magnitude of relative improvement and likelihood of achieving an MCID based upon the patients individual preoperative SNOT-22 score level. Thus, during the provision of ESS for CRS, it would be important to measure preoperative QoL to help optimize the patient’s understanding of potential clinical outcomes in order to improve preference-sensitive care for CRS.

The purpose of this study was to generate data to help inform patient decision-making for ESS by providing the chance of achieving an MCID improvement after ESS based on their preoperative SNOT-22 score. Outcomes from this study suggest that when the SNOT-22 score is less than 30 for patients with CRSsNP and CRSwNP, there was less than a 55% chance of obtaining an MCID improvement. Furthermore, on average patients with SNOT-22 scores less than 20 received a worse outcome after ESS. This finding suggests that the patient-provider decision should carefully consider ESS when the patients preoperative SNOT-22 score is less than 20 points since surgery may not provide a desired clinical outcome. Conversely, patients with a preoperative SNOT-22 score higher than 30 points typically have a greater than 80% chance of obtaining an MCID and receive an estimated 50% improvement in their SNOT-22 score.

Although outcomes from this study will help to inform patients regarding the chances of receiving an MCID and the degree (%) of improvement to expect after ESS, there are several factors that must be considered when interpreting these results. First, the MCID is the lowest degree of change in a particular metric that a patient will notice and may not necessarily reflect the patients’ expectation for improvement after ESS. Furthermore, the definition of a ‘clinically significant’ improvement in QoL is vague and poorly defined after ESS. For example, a patient who receives an MCID improvement of exactly 9 points in the SNOT-22 after ESS may not be satisfied with this outcome due to a persistent measureable burden of disease, even though they achieved a noticeable improvement. In order to address the inherent challenge of using the MCID as a surrogate for a clinically significant change to a patient, this study also provided the relative percentage of improvement after ESS which can best reflect the true magnitude of postoperative improvements relative to preoperative symptom severity7. To optimize patient understanding, it would likely be helpful to provide information on both the probability of achieving an MCID and degree of relative improvement after ESS.

Second, it is very important to understand that there are clinical scenarios which involve sinus pathology with minimally affected SNOT-22 scores but yet still require ESS. For example, uncomplicated mucoceles, silent sinus syndrome, or mycetoma’s typically have normal to minimally affected SNOT-22 scores but these patients still require ESS to correct the underlying disease process. Therefore, the data from this study should not be used as a pre-requisite for ESS or third party reimbursement decision. The purpose of this study is to improve the patient-physician shared decision-making process and optimize preference-sensitive care for CRS.

Third, while it is not clear that numeric reductions in Likert scales truly represent proportional burdens of disease, the percentage’s provided will still assist in counseling patients prior to ESS since physicians can inform patients that on average what percentage change they can expect. For example, patients with CRSsNP who have a SNOT-22 score between 60-69 receive an estimated 50% reduction (-49.6%; Table 4) in their reported symptom severity as measured by the SNOT-22 after ESS as compared to patients with a SNOT-22 score between 10-19 who received a 15% increase (+14.8%) in score after ESS. Therefore, it would be helpful to discuss both the relative percentage of improvement along with the probability of receiving an MCID of 9 points with patients prior to ESS.

In addition to defining success as achieving an MCID or a percentage improvement in baseline symptoms, another method to examine successful outcomes would be achieving a defined “normal” or “near normal” threshold for postoperative SNOT-22 scores. Prior studies using SNOT-22 in patients with no sinus disease resulted in scores ranging from 0-50 with means of 8.1 and 9.3, respectively4,12. Unfortunately, these populations were not controlled for age, gender, race or other factors, thus a “normal” SNOT-22 score is still uncertain. Our results demonstrate that even though 80% of patients with SNOT-22 scores over 30 improve by an average of 48% it is very likely that they are still left with a significant burden of disease and remain more symptomatic than healthy controls. Future research should work to improve the definitions for a clinically significant improvement after ESS.

Fourth, readers should consider the categorization of patients based on polyp status. With emerging research elucidating specific CRS endotypes13, dichotomizing patients into cohorts based on polyp status likely produces inherent heterogeneity within the patients groups thus influencing the accuracy of patient-specific outcomes. However, at the present time, using polyp status to counsel patients is a simple clinical categorization that all physicians can use in the office setting and future research should begin to refine patient outcomes after ESS using more specific endotype markers of disease.

Lastly, SNOT-22 groups on either extreme of the scoring scale contained small sample sizes, which makes it difficult to provide accurate statistical results and will introduce larger degrees of uncertainty around the means for these groupings. However, despite this study using a large prospective study of 551 CRS patients, it demonstrates the inherent challenge of studying patients with SNOT-22 scores at the extreme high and low ranges and emphasizes the need to develop larger collaborative CRS databases. Despite the factors outlined above, this study is strengthened by the accurate longitudinal data collection and large overall sample size.

Using a PROM, such as the SNOT-22, can be a valuable tool for the physician to use during the assessment of a patient with CRS. Determining the overall SNOT-22 score, and identifying the specific sub-domains most affected, can provide valuable information capable of being used during the decision making process. Furthermore, the physician could use the SNOT-22 responses to specifically address the symptoms that are most bothersome to the patient which would not only improve patient-physician relationship but also focus the consultation into a more efficient use of a time. We would encourage physicians to not only routinely measure SNOT-22 (or another QoL PROM) but utilize the SNOT-22 during the active management process of a patient with CRS.

Conclusions

Current evidence suggests that patients with CRS who are candidates for ESS make decisions based on the degree of their preoperative QoL impairment. The purpose of this study was to improve patient understanding of their surgical outcomes while they make preference-sensitive decisions regarding electing ESS. Outcomes from this study suggest that patients with a preoperative SNOT-22 score higher than 30 points receive a greater than 75% chance of achieving an MCID and on average obtain a 46% relative improvement in their QoL after ESS. Patients with SNOT-22 score of less than 20 typically fail to receive QoL improvement after ESS. Information from this study can be used to improve patient understanding of the potential outcomes after ESS and may improve preference-sensitive care for CRS.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. T. L. Smith, Dr. Z. M. Soler, and J. Mace are supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH: R01 DC005805).

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institutes of Health had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript or decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict(s) of Interest:

LR: None

ZMS: Grant support from the NIH/NIDCD

JCM: Grant support from the NIH/NIDCD

ASC: None

RJS: Consultant for BrainLAB, Olympus, United Allergy; Grant support from Medtronic, Arthrocare, Intersect ENT, Optinose, NeilMed.

TLS: Consultant for Intersect ENT Inc. (Menlo Park, CA). Grant support from NIH/NIDCD

References

- 1.Wennberg JE. Practice variation: implications for our health care system. Manag Care. 2004;13:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soler ZM, Rudmik L, Hwang PH, Mace JC, Schlosser RJ, Smith TL. Patient-centered decision making in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2341–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.24027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Bodner T, et al. SNOT-22 quality of life domains differentially predict treatment modality selection in chronic rhinosinusitis. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/alr.21408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clinical otolaryngology: official journal of ENT-UK; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2009;34:447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007;137:S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudmik L, Mace J, Ferguson BJ, Smith TL. Concurrent septoplasty during endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: does it confound outcomes assessment? The Laryngoscope. 2011;121:2679–83. doi: 10.1002/lary.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart MG, Donovan DT, Parke RB, Jr., Bautista MH. Does the severity of sinus computed tomography findings predict outcome in chronic sinusitis? Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2000;123:81–4. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.105922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KA, Rudmik L. Impact of continued medical therapy in patients with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2014;4:34–8. doi: 10.1002/alr.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith KA, Smith TL, Mace JC, Rudmik L. Endoscopic sinus surgery compared to continued medical therapy for patients with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/alr.21366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TL, Kern R, Palmer JN, et al. Medical therapy vs surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, multi-institutional study with 1-year follow-up. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2013;3:4–9. doi: 10.1002/alr.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TL, Litvack JR, Hwang PH, et al. Determinants of outcomes of sinus surgery: a multi-institutional prospective cohort study. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;142:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeolekar AM, Dasgupta KS, Khode S, Joshi D, Gosrani N. A Study of SNOT 22 Scores in Adults with no Sinonasal Disease. J Rhinolaryngo-Oto. 2013;1:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, et al. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: a PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;131:1479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]