Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

We have previously developed a multigene expression model of tumor radiosensitivity (RSI) with clinical validation in multiple independent cohorts (breast, rectal, esophageal, and head and neck). The purpose of this study was to assess differences in RSI scores between primary colon cancer and metastases.

Methods and Materials

Patients were identified from our institutional IRB approved prospective observational protocol. A total of 704 metastatic and 1,362 primary lesions were obtained from a de-identified meta-data pool. RSI was calculated using the previously published ranked based algorithm. An independent cohort of 29 lung or liver colon metastases treated with 60 Gy in 5 fractions stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) was used for validation.

Results

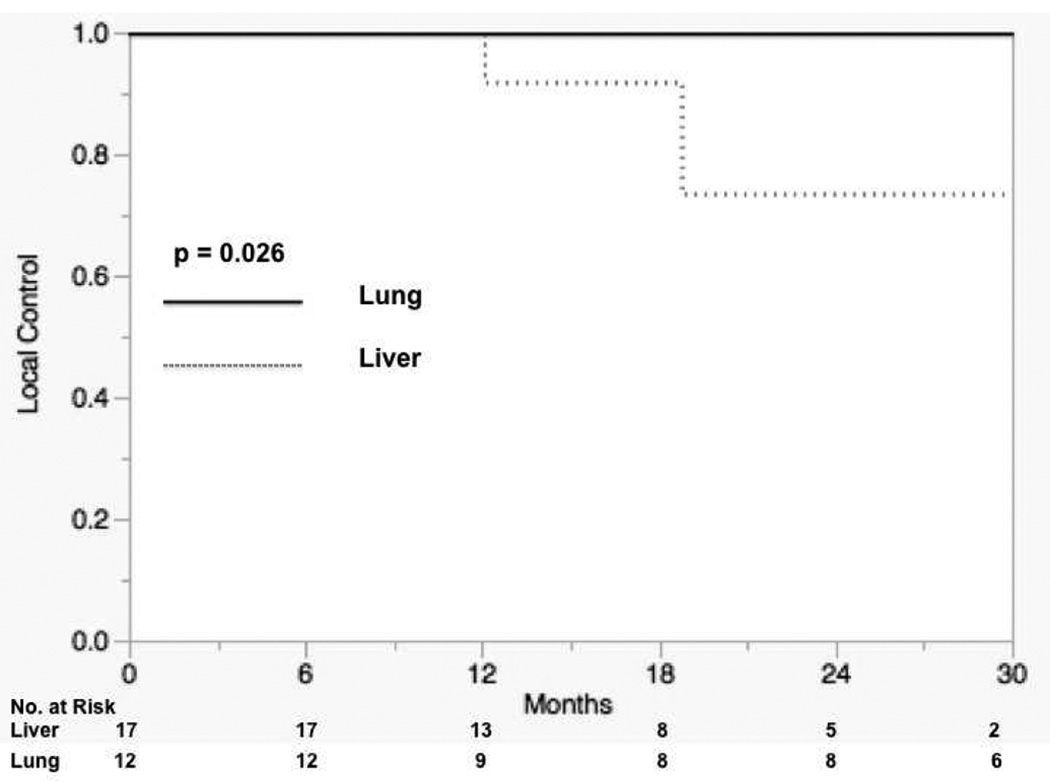

The most common sites of metastases included liver (n=374; 53%), lung (n=116; 17%), and lymph nodes (n=40; 6%). Sixty percent of metastatic tumors compared with 54% of primaries were in the RSI-radioresistant (RSI-RR) peak, suggesting that, metastatic tumors may be slightly more radioresistant than primaries (p=0.01). In contrast, when we analyzed metastases based on anatomical site, we uncovered large differences in RSI. The median RSIs for metastases in descending order of radioresistance were ovary (0.48), abdomen (0.47), liver (0.43), brain (0.42), lung (0.32), and lymph nodes (0.31), p<0.0001. These findings were confirmed when the analysis was restricted to lesions from the same patient (n=139). In our independent cohort of treated lung and liver metastases, lung metastases had an improved local control (LC) rate over patients with liver metastases (2 yr LC 100% vs. 73.0%, p=0.026).

Conclusions

Assessment of radiosensitivity between primary and metastatic tissues of colon cancer histology, reveals significant differences based on anatomical location of metastases. These initial results warrant validation in a larger clinical cohort.

Introduction

Studies have shown long-term survival in patients treated for resection of limited metastatic disease [1–3]. Similarly, aggressive treatment to a single site of metastatic disease in the brain has shown improved overall survival (OS) [4,5]. Treatment of oligometastatic disease has become more common among radiation oncologists in recent years [6–8]. Salama et al. reported on the treatment of 1 to 5 metastatic sites with SBRT to all known cancer sites with long term OS reported [9]. There are known biologic differences between primary and metastatic lesions [10]. Institutional reports have suggested a dose response relationship with the treatment of SBRT in patients with lung and liver metastases [11–13].

Significant differences in the radiosensitivity of tumor types are believed to exist based on the α/β ratio of the cell survival curve. A tool to help in the selection of a dose and fractionation schedule for metastatic disease based on anatomical location may have large implications in the management of patients with oligometastatic disease. We have previously developed a multigene expression model of tumor radiosensitivity [14]. This model has been validated in multiple independent clinical cohorts including breast, rectal, esophageal, and head and neck cancers [14,15]. This model predicts a radiosensitivity index (RSI) that is directly proportional to tumor radioresistance, (RSI, high index = radioresistance). The purpose of this study was to assess differences in RSI between primary colon cancer and metastases as well as differences in RSI between primary and metastatic colon cancer from the same patient. In addition, we validated these results with confirmation in an independent clinical cohort of patients treated to sites of oligometastatic disease of colon primary.

Materials and Methods

Patients were identified from the IRB-approved XXX prospective observational protocol at our institution. Deidentified data from a total of 704 metastatic and 1,362 primary colon cancer lesions were obtained from the XXX meta-data pool.

RNA preparation and gene expression profiling

These methods have been described previously [16,17]. The expression values for the samples in this study and corresponding genes were extracted from the XXX database. These expression values have been normalized against a median sample using IRON [18]. An RNA-quality related batch-effect was identified in the resulting normalized data, which was removed by training a partial least squares (PLS) model[19] to the BioAnalyzer BA_RIN RNA quality metric, then subtracting the first PLS component.

Radiosensitivity Signature

The previously tested 10 gene assay was run on tissue samples and RSI was calculated using the previously published ranked based algorithm [14,20]. Briefly, each of the 10 genes in the assay was ranked according to gene expression [from the highest (10) to the lowest expressed gene (1)]. RSI was determined using the previously published ranked based linear algorithm:

RSI = −0.0098009*AR + 0.0128283*cJun +

0.0254552*STAT1 − 0.0017589*PKC −

0.0038171*RelA + 0.1070213*cABL −

0.0002509*SUMO1 − 0.0092431*CDK1 −

0.0204469*HDAC1 − 0.0441683* IRF1

SBRT Patient Cohorts

Using our institutional database of patients treated for colon cancer metastases, a retrospective analysis was conducted on all consecutive lung and liver lesions treated with SBRT with a 6 month minimum follow-up using a similar dose and fractionation schedule of 60 Gy in 5 fractions. Each patient was immobilized using the Body-Fix whole-body or thoracic-T double vacuum immobilization system (Medical Intelligence, Schwabmünchen, Germany). Axial CT images were obtained on a Light Speed RT 16-slice CT simulator (GE HealthCare, Milwaukee, WI) with image acquisition set at 3 mm slice thickness. Four-dimensional CT imaging was performed using Varian RPM (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). In some cases, respiratory gating was employed, using an infrared reflector placed on the patient’s chest. Prior to each treatment an initial cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan was acquired, a match was performed, and the shift was applied. Any shift greater than 0.3 cm required a second CBCT acquisition to verify position. For lung lesions, the planning target volume (PTV) equaled the gross tumor volume (GTV) plus 7 mm superiorly and inferiorly and 5 mm radially. Dose constraints included the spinal cord 0.03 cc <17 Gy, lung V20 <10%, heart V32 <15 cc, esophagus V27.5 < 5 cc, chestwall V30 <30 cc, and brachial plexus V30 <3 cc. In liver lesions, the PTV=GTV +5 mm. Max doses to the bowel, cord, esophagus, and stomach were 30 Gy, 20 Gy, 20 Gy, and 30 Gy, respectively. In addition, mean dose to the kidneys was <10 Gy, liver-GTV V15<700 cc, lung V10 <1500 cc, and heart mean <10 Gy. In all lung and liver lesions the PTV was covered by 90% of the prescribed dose.

Following treatment, patients were followed by the treating radiation oncologist or medical oncologist with imaging at 2–3 month intervals. Radiologic imaging was reviewed to determine local control. Local failure was defined by an increase in the size of the previously irradiated area according to the RECIST criteria version 1.1 [21].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 11 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the cohort including median and range for continuous variables or counts and percentages for categorical variables. When comparing RSI-RR to RSI-RS lesions, a Fisher’s exact test was used. When conducting a paired analysis of RSI values from primary and metastatic lesions across the same patient an Exact Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used and an Exact Kruskal-Wallis Test with Monte Carlo Estimation when conducting the analysis based on anatomical location. The OS and local control (LC) rates were calculated from the date of treatment to the date of death or progression using the Kaplan–Meier method. A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Distribution plots were generated using MATLAB (version R2013a Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc., 2010).

Results

Differences in the RSI Index of Colon Metastases

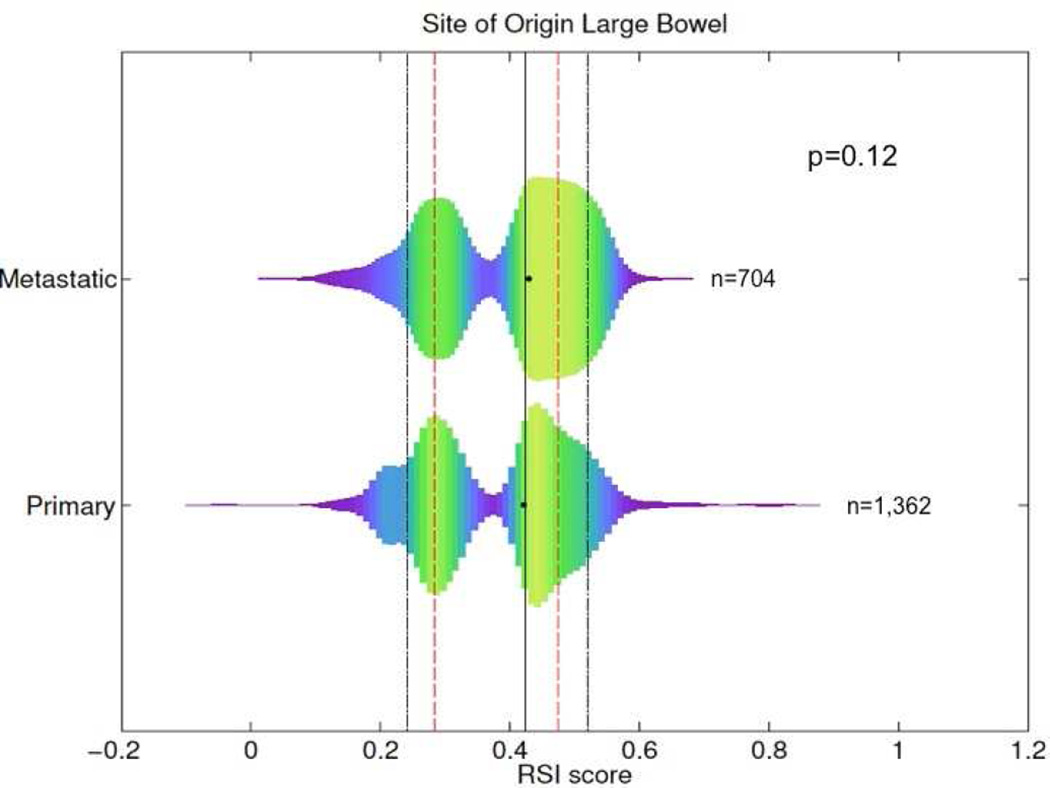

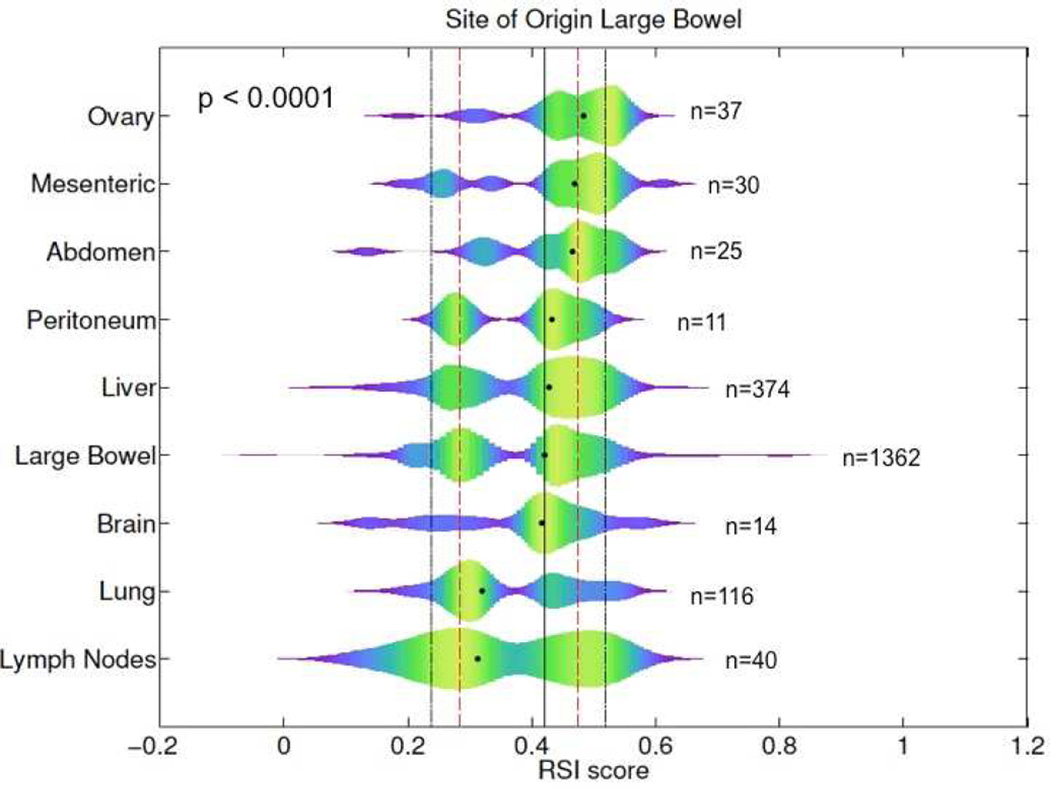

The most common sites of metastases included the liver (n=374; 53%), lung (n=116; 17%), and lymph nodes (n=40; 6%). We found that RSI exhibits a bi-modal distribution with a minimum density between the two peaks at RSI=0.3745, which was used to define radiosensitivity peaks (<0.3745 = radiosensitive; ≥0.3745 = radioresistant). The median RSI between metastatic and primary tissues was 0.43 and 0.42 (p=0.12), respectively, Figure 1. Sixty percent of metastatic tumors compared with 54% of primaries were in the RSI-radioresistant (RSI-RR) peak, suggesting that, metastatic tumors may be slightly more radioresistant than primaries (p=0.01). Large differences were noted when assessing RSI values based on anatomical site of metastases. The median RSIs for metastases in descending order of radioresistance were ovary (0.48), abdomen (0.47), liver (0.43), brain (0.42), lung (0.32), and lymph nodes (0.31), p<0.0001. The median RSI based on anatomical location is displayed graphically in Figure 2. Metastases to ovary, abdomen, and mesentery were predominantly RSI-radioresistant (RSI-RR) (ovary-RSI-RR=86%, p=0.0001, abdomen-RSI-RR=76%, p=0.04, and mesentery-RSI-RR=73%, p=0.06). In contrast, metastases to lung were more commonly RSI-radiosensitive (RSI-RS) (lung-RSI-RS=58%, p=0.003) while metastases to liver and brain had similar distribution as primaries.

Figure 1.

Differences in RSI between primary and colon cancer metastases, black and red lines represent the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile of RSI values across all samples.

Figure 2.

Differences in RSI of colon cancer metastases based on anatomical location, black and red lines represent the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile of RSI values across all samples.

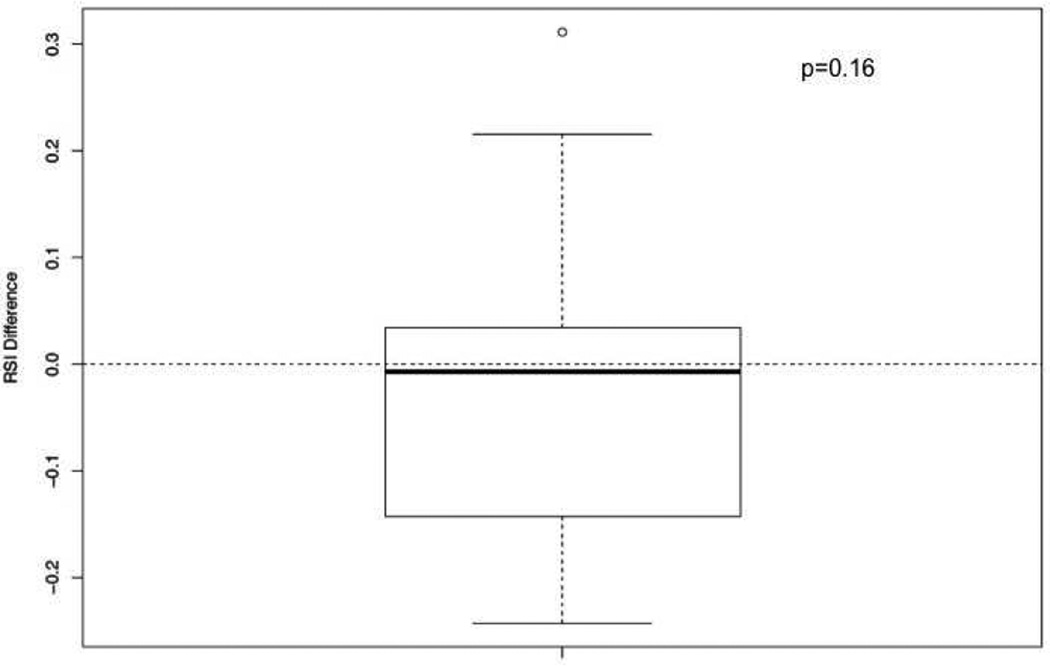

Differences in the RSI Index of Colon Primaries and Metastases in the Same Patient

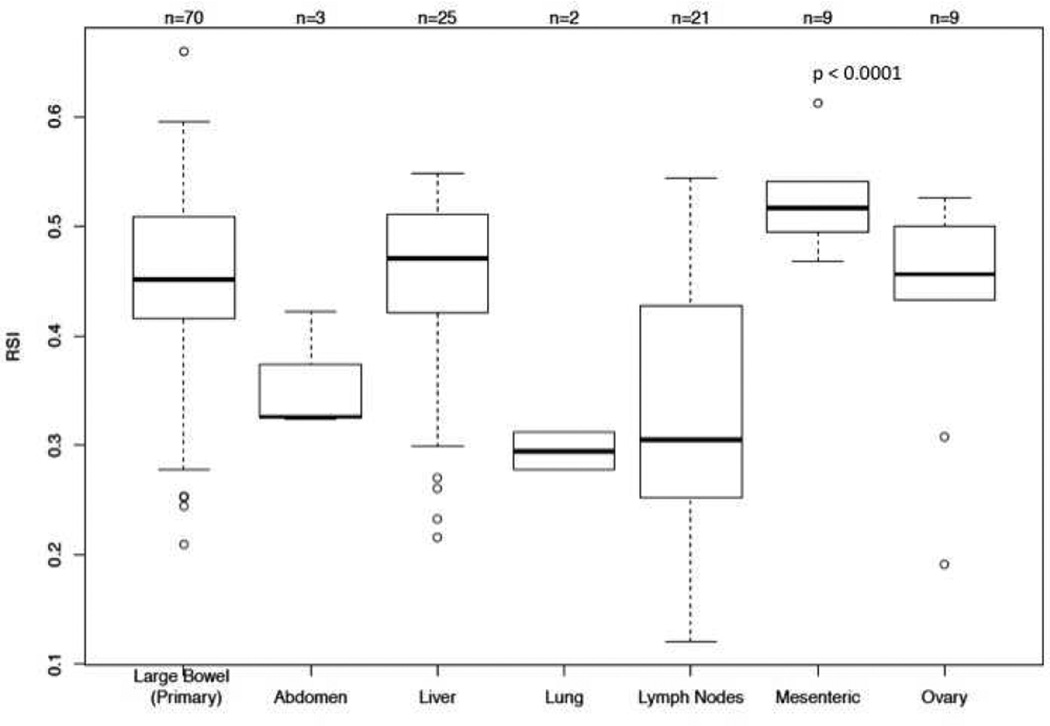

A total of 70 primary and 69 metastatic lesions were identified when the analysis was restricted to lesions from the same patient. The most common location for metastatic lesions in this subset were liver (n=25; 18.0%), lymph nodes (n=21; 15.1%), mesentery (n=9; 6.5%), ovary (n=9; 6.5%), abdomen (n=3; 2.2%), and lung (n=2; 1.4%). The median RSI for primary lesions was 0.45 and 0.45 for metastatic lesions (p=0.33) from the same patient. A matched pair analysis between primary and metastases from the same patient showed no difference, Figure 3. However, significant differences were noted based on the anatomical location of metastases. The median RSIs for metastases in descending order of radioresistance were mesenteric (0.52), liver (0.47), ovary (0.46), abdomen (0.33), lymph nodes (0.31), and lung (0.29) (p<0.0001), Figure 4

Figure 3.

Differences in RSI between primary and metastases from the same patient.

Figure 4.

Differences in RSI between primary and metastatic lesions based on anatomical location from the same patient.

Clinical Outcomes in Lung and Liver Metastases Treated with SBRT

An independent cohort of 23 patients with 29 lesions were treated for oligometastatic disease from the colon. A total of 12 lung and 17 liver lesions were treated with a dose fractionation schedule of 60 Gy in 5 fractions. Characteristics of lesions treated are shown in Table 1. Median follow-up for liver lesions was 14.3 months (range: 6.8–13.7 months) and 27.8 months (range: 6.1–46.3 months) for lung lesions. There were no differences noted between lung and liver lesions with respect to maximum diameter of the lesion (p=0.52). There was a significant difference in local control between lung and liver lesions. Three patients treated for liver lesions exhibited local failure in the previously irradiated tumor bed on follow-up imaging while no patients treated for lung metastases exhibited local failure. The 12 and 24 month Kaplan-Meier rate of LC for lung lesions was 100% compared to 100% and 73.0% for liver lesions (p=0.026), Figure 5. There was no significant difference in OS between patients treated for lung and liver lesions with 12 and 24 month rates of 100% and 78.1% for patients treated for liver metastases and 100% and 89% for patients treated for lung metastases (p=0.98).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients treated for lung and liver metastases

| Lung | Liver | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 9 | 14 | |

| Age (years) | 66 (49–74) | 69 (52–89) | 0.48 |

| Male/Female | 3/6 | 9/5 | 0.1 |

| Lesions (n) | 12 | 17 | |

| Diameter of Lesion (cm) | 1.5 (0.7–3.5) | 1.8 (0.6–4.6) | 0.52 |

| Follow-Up (months) | 27.8 (6.1–46.3) | 14.3 (6.8–37) |

Figure 5.

Local control rates between lung and liver colon cancer metastases.

Discussion

In this first of its kind analysis on the radiosensitivity of colon metastases based on anatomical site, we present several intriguing findings. First, we find that significant differences were noted in our RSI index based on the anatomical location of the metastatic lesion. These results were confirmed when restricting our analysis to primary and metastatic lesions from the same patient. Finally, using an independent cohort of metastatic colon cancer patients treated for oligometastatic disease with a similar SBRT dose and fractionation schedule, we find significant differences in local control between the treatment of liver and lung metastases.

The treatment of oligometastatic disease has become increasingly more common in recent years. Typically defined as extension of primary disease into 5 or less sites, the management of oligometastatic patients represents an active area of oncologic debate and research. Local treatments include surgery, radiation treatment, and radiofrequency ablation. Salama et al. published a prospective dose escalation trial of patients with 1 to 5 metastases treated with SBRT [9]. The starting dose for all sites was 24 Gy (three 8 Gy fractions). A 3 × 3 dose escalation schema was used with a maximum dose of 48 Gy but the maximal tolerated dose was not reached. The majority of lesions were located in the lung (36.3%), lymph nodes (19.4%), and liver (19.4%). The study reported 1 and 2 year progression-free survival rates of 33% and 22% with OS rates of 81% and 57%, respectively. Results from the University of Rochester also indicate potential in treating patients with oligometastatic disease with 2-year OS, freedom from distant metastasis (FFDM), and LC rates of 74%, 52%, and 87%, respectively for breast cancer patients and rates of 39%, 28%, and 74%, respectively for non-breast cancer patients [22].

The optimal dosing schedule in the treatment of oligometastatic lesions remains a topic of debate. At our institution, a similar dosing schedule is used for patients who present with oligometastatic lung and liver metastases. Various fractionation schedules have been reported for patients treated for lung [23–25] and liver metastases [13,26,27]. Dose escalation was reported to improve local control rates in a phase I dose-escalation trial of hepatic metastases from Rule et al. The study randomized 27 patients to 30 Gy in 3 fractions, 50 Gy in 5 fractions, and 60 Gy in 5 fractions [12]. Actuarial 24-month LC rates for the 30, 50, and 60 Gy cohorts were 56%, 89%, and 100%, respectively. A significant difference was noted in local control between the 60 and 30 Gy cohorts (p = 0.009), with the authors recommending 60 Gy in 5 fractions as safe and tolerable in their patient cohort [12]. Data from the University of Colorado suggests a dose response relationship in the treatment of liver and lung metastases [11]. McCammon et al. reported on 246 lesions treated with 3 fraction SBRT. Lesions treated to a dose of 54 Gy or greater had a 3-year LC of 89.3% compared with 59.0% and 8.1% for those treated to 36–53.9 Gy and less than 36 Gy, respectively. The study noted a trend on univariate analysis towards a difference in outcomes between treatment site, lung vs. liver (p=0.12) but not on multivariate analysis (p=0.24). However, unlike our analysis the study was not restricted to lesions of colon primary. Fumagalli et al. suggested a difference in outcome based on anatomical location[26]. The study assessed outcomes in hepatic or pulmonary oligometastases of which 70% were of digestive primary. An improved disease free survival was noted in patients treated to pulmonary metastases on univariate analysis (p=0.02). Taken together, these results at least suggest that there may be a difference in SBRT outcomes based on treatment location and dose selection.

An assessment of the RSI score in colon cancer metastases suggests that anatomical location plays a role in dictating radiosensitivity, which may have implications for dose selection. Significant differences were found in the RSI index based on tumor location as seen in figure 2. These differences were also noted when the analysis was limited to lesions from the same patient. There are obvious histologic differences in the parenchyma and vasculature of these organ systems, which we hypothesize might explain the differences in radiosensitivity‥

With this information, we hypothesize that metastases with higher RSI scores may benefit from higher doses of RT whereas lesions with lower RSI scores may do comparably better with equivalent doses of RT. A dose of 60 Gy in 5 fractions was used to treat all patients in this study and resulted in failures of small lesions in the liver. Our study suggests that dose escalation may be considered for radioresistant metastatic tumor locations such as the liver; however, this must be balanced with critical organ constraints [28,29]. Further clinical study is needed to determine how to optimize dose and fractionation schedules based on RSI. However, one possible approach is to develop patient-specific α/β ratios based on RSI. Studies integrating RSI into the linear quadratic model are currently underway in our group.

Although these initial findings are quite intriguing and novel to the biology and treatment of oligometastatic disease, they are not without limitations. First, genomic data was obtained from our institutional de-identified meta-data pool and thus clinical and baseline demographic characteristics of the 704 metastatic and 1,362 primary lesions were not available. Second, RSI values for the 29 liver and lung metastases were not collected and follow-up time following treatment was limited. Another question is how our index, which has been developed in cell lines based on the surviving fraction of cells at 2 Gy (SF2) and validated with conventional fractionation schedules relates to the hypofractionation cohort used for validation in this study. Finally, since RSI was not determined in the SBRT cohort, this only represents indirect evidence for the clinical validity of RSI in this clinical setting and no direct inferences on RSI are possible. However, we think the data here provides an interesting hypothesis that may prove the foundation of further basic and clinical research into the intrinsic radiosensitivity of metastases. Ultimately, these initial results will need to be validated in a larger clinical cohort with direct assessment of RSI. However, our initial validation cohort is unique in that all patients were treated with a similar dose and fractionation schedule without differences in factors influencing local control such as lesion size.

In this analysis assessing radiosensitivity between primary and metastatic tissues of colon cancer histology, significant differences were noted based on the anatomical location of metastases. Radiosensitivity was affected by the anatomical site of the metastases as noted by significant differences in RSI scores. Initial validation with retrospective clinical data appears to verify our findings. Future directions will include validation in a large clinical cohort with potential correlation in other primary histologies and research into the molecular basis for these radiosensitivity differences.

The radiosensitivity signature (RSI) has been previously validated. We applied the RSI signature to primary and metastatic colon cancer tissue samples and noted large differences in RSI based on the anatomical site of metastases p<0.0001, which persisted when the analysis was restricted to lesions from the same patient p<0.0001. Initial clinical validation in a cohort of 29 liver and lung metastases treated with SBRT confirmed our results.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institutes of Health (R21CA101355/R21CA135620), US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, National Functional Genomics Center (170220051) and Bankhead-Coley Foundation (09BB-22) and the Debartolo Family Personalized Medicine Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: Steven A. Eschrich PhD and Javier F. Torres-Roca MD report stock and leadership in Cvergenx, Inc. and royalty and patents on RSI

Presented in Oral Form at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology, September 13th–17th, 2014, San Francisco, CA

REFERENCES

- 1.Fong Y, Cohen AM, Fortner JG, Enker WE, Turnbull AD, Coit DG, Marrero AM, Prasad M, Blumgart LH, Brennan MF. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:938–946. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long-term results of lung metastasectomy: Prognostic analyses based on 5206 cases. The international registry of lung metastases. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1997;113:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aloia TA, Vauthey JN, Loyer EM, Ribero D, Pawlik TM, Wei SH, Curley SA, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK. Solitary colorectal liver metastasis: Resection determines outcome. Archives of surgery. 2006;141:460–466. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.5.460. discussion 466-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Dempsey RJ, Mohiuddin M, Kryscio RJ, Markesbery WR, Foon KA, Young B. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: A randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1485–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW, Flanders AE, Gaspar LE, Schell MC, Werner-Wasik M, Demas W, Ryu J, Bahary JP, Souhami L, Rotman M, Mehta MP, Curran WJ., Jr Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: Phase iii results of the rtog 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed KA, Stauder MC, Miller RC, Bauer HJ, Rose PS, Olivier KR, Brown PD, Brinkmann DH, Laack NN. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in spinal metastases. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012;82:e803–e809. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okunieff P, Petersen AL, Philip A, Milano MT, Katz AW, Boros L, Schell MC. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (sbrt) for lung metastases. Acta oncologica. 2006;45:808–817. doi: 10.1080/02841860600908954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salama JK, Chmura SJ, Mehta N, Yenice KM, Stadler WM, Vokes EE, Haraf DJ, Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. An initial report of a radiation dose-escalation trial in patients with one to five sites of metastatic disease. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14:5255–5259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salama JK, Hasselle MD, Chmura SJ, Malik R, Mehta N, Yenice KM, Villaflor VM, Stadler WM, Hoffman PC, Cohen EE, Connell PP, Haraf DJ, Vokes EE, Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for multisite extracranial oligometastases: Final report of a dose escalation trial in patients with 1 to 5 sites of metastatic disease. Cancer. 2012;118:2962–2970. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rofstad EK. Radiation sensitivity in vitro of primary tumors and metastatic lesions of malignant melanoma. Cancer research. 1992;52:4453–4457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCammon R, Schefter TE, Gaspar LE, Zaemisch R, Gravdahl D, Kavanagh B. Observation of a dose-control relationship for lung and liver tumors after stereotactic body radiation therapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;73:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rule W, Timmerman R, Tong L, Abdulrahman R, Meyer J, Boike T, Schwarz RE, Weatherall P, Chinsoo Cho L. Phase i dose-escalation study of stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with hepatic metastases. Annals of surgical oncology. 2011;18:1081–1087. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herfarth KK, Debus J, Lohr F, Bahner ML, Rhein B, Fritz P, Hoss A, Schlegel W, Wannenmacher MF. Stereotactic single-dose radiation therapy of liver tumors: Results of a phase i/ii trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:164–170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eschrich SA, Pramana J, Zhang H, Zhao H, Boulware D, Lee JH, Bloom G, Rocha-Lima C, Kelley S, Calvin DP, Yeatman TJ, Begg AC, Torres-Roca JF. A gene expression model of intrinsic tumor radiosensitivity: Prediction of response and prognosis after chemoradiation. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;75:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eschrich SA, Fulp WJ, Pawitan Y, Foekens JA, Smid M, Martens JW, Echevarria M, Kamath V, Lee JH, Harris EE, Bergh J, Torres-Roca JF. Validation of a radiosensitivity molecular signature in breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:5134–5143. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smid M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Yu J, Klijn JG, Foekens JA, Martens JW. Subtypes of breast cancer show preferential site of relapse. Cancer research. 2008;68:3108–3114. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawitan Y, Bjohle J, Amler L, Borg AL, Egyhazi S, Hall P, Han X, Holmberg L, Huang F, Klaar S, Liu ET, Miller L, Nordgren H, Ploner A, Sandelin K, Shaw PM, Smeds J, Skoog L, Wedren S, Bergh J. Gene expression profiling spares early breast cancer patients from adjuvant therapy: Derived and validated in two population-based cohorts. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2005;7:R953–R964. doi: 10.1186/bcr1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsh EA, Eschrich SA, Berglund AE, Fenstermacher DA. Iterative rank-order normalization of gene expression microarray data. BMC bioinformatics. 2013;14:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wold SRA, Wold H, Dunn I, WJ The collinearity problem in linear regression. The partial least squares (pls) approach to generalized inverses. SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing. 1984;5:735–743. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eschrich S, Zhang H, Zhao H, Boulware D, Lee JH, Bloom G, Torres-Roca JF. Systems biology modeling of the radiation sensitivity network: A biomarker discovery platform. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;75:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised recist guideline (version 1.1) European journal of cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milano MT, Katz AW, Zhang H, Okunieff P. Oligometastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: Long-term follow-up of prospective study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012;83:878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wulf J, Haedinger U, Oppitz U, Thiele W, Mueller G, Flentje M. Stereotactic radiotherapy for primary lung cancer and pulmonary metastases: A noninvasive treatment approach in medically inoperable patients. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2004;60:186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rusthoven KE, Kavanagh BD, Burri SH, Chen C, Cardenes H, Chidel MA, Pugh TJ, Kane M, Gaspar LE, Schefter TE. Multi-institutional phase i/ii trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung metastases. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:1579–1584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricardi U, Filippi AR, Guarneri A, Ragona R, Mantovani C, Giglioli F, Botticella A, Ciammella P, Iftode C, Buffoni L, Ruffini E, Scagliotti GV. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung metastases. Lung cancer. 2012;75:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fumagalli I, Bibault JE, Dewas S, Kramar A, Mirabel X, Prevost B, Lacornerie T, Jerraya H, Lartigau E. A single-institution study of stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with unresectable visceral pulmonary or hepatic oligometastases. Radiation oncology. 2012;7:164. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rusthoven KE, Kavanagh BD, Cardenes H, Stieber VW, Burri SH, Feigenberg SJ, Chidel MA, Pugh TJ, Franklin W, Kane M, Gaspar LE, Schefter TE. Multi-institutional phase i/ii trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:1572–1578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tse RV, Hawkins M, Lockwood G, Kim JJ, Cummings B, Knox J, Sherman M, Dawson LA. Phase i study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:657–664. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kavanagh BD, Schefter TE, Cardenes HR, Stieber VW, Raben D, Timmerman RD, McCarter MD, Burri S, Nedzi LA, Sawyer TE, Gaspar LE. Interim analysis of a prospective phase i/ii trial of sbrt for liver metastases. Acta oncologica. 2006;45:848–855. doi: 10.1080/02841860600904870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]