Abstract

Importance

Despite antirestenotic efficacy of coronary drug-eluting stents (DES) compared with bare metal stents (BMS), the relative risk of stent thrombosis and adverse cardiovascular events is unclear. Although dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond one year provides ischemic event protection following DES, ischemic event risk is perceived to be less following BMS and the appropriate duration of DAPT following BMS is unknown.

Objective

To compare: (1) rates of stent thrombosis and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE; composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) after 30 vs. 12 months of thienopyridine in patients treated with BMS taking aspirin; and (2) treatment duration effect within the combined cohorts of randomized DES or BMS-treated patients as prespecified, secondary analyses of the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study.

Design, Setting, Participants

International, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, comparing extended (30 months) thienopyridine versus placebo in aspirin-treated patients who completed 12 months of DAPT without bleeding or ischemic events post-stenting. Study initiation August 2009 with last follow-up visit May 2014.

Exposure/Intervention

Continued thienopyridine or placebo at months 12-30 after stenting, in 11648 randomized patients treated with aspirin, of whom 1687 received BMS and 9961 DES.

Main Outcome and Measures

Stent thrombosis, MACCE, moderate/severe bleeding.

Results

Among 1687 BMS-treated patients randomized to continued thienopyridine vs. placebo, rates of stent thrombosis were 0.5% vs. 1.11%, (N=4 vs. 9, hazard ratio 0.49, 95% CI 0.15-1.64, P=0.24), MACCE 4.04% vs. 4.69%, (N=33 vs. 38, hazard ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.57-1.47, P=0.72) and moderate/severe bleeding 2.03% vs. 0.90% (N=16 vs. 7, P=0.07), respectively. Among all 11,648 randomized patients (both BMS- and DES-treated), stent thrombosis rates were 0.41% vs. 1.32%, (N=23 vs. 74, hazard ratio 0.31, 95% CI 0.19-0.50, P<0.001), MACCE 4.29% vs. 5.74% (N=244 vs. 323, hazard ratio 0.73, 95% CI 0.62-0.87, P<0.001), and moderate/severe bleeding 2.45% vs. 1.47% (N=135 vs. 80, P<0.001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients undergoing coronary stenting with BMS and who tolerated 12 months of thienopyridine, continuing thienopyridine for an additional 18 months compared with placebo did not result in statistically significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis, MACCE, or moderate/severe bleeding. However, the BMS subset may have been underpowered to identify such differences and further trials are suggested. (DAPT ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00977938).

Introduction

While current clinical practice guidelines recommend a minimum of only 1 month of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after bare metal stent (BMS) placement following elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; compared with 6-12 months for drug-eluting stents [DES]),1,2 patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) benefit from 12 months of therapy whether or not PCI with stenting is performed.3 Although randomized trial results (the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study)4 showed a reduction in stent thrombosis and non-stent related myocardial infarction (MI) with thienopyridine therapy beyond 12 months following DES (among patients tolerating DAPT to 12 months), few trials have assessed optimal duration of DAPT following BMS.5 Because BMS remain a commonly used alternative treatment strategy to DES, particularly for patients who present with ACS or in whom DAPT has perceived increased bleeding risk,6,7 we aimed to compare (1) rates of stent thrombosis or major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in randomized BMS-treated patients and (2) treatment duration effect among all randomized patients in the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study.

Methods

Study Objectives and Hypotheses

We compared the randomized treatment effect of continued thienopyridine vs. placebo beyond 12 months with regard to stent thrombosis, MACCE, and bleeding after randomization until the completion of study drug treatment at 30 months among BMS-treated patients as well as the combined BMS- and DES-treated cohort. As a post hoc analysis, we assessed the consistency of treatment duration effect between patients treated with BMS or DES.

Study Design

The DAPT Study design has previously been described.8 This double-blind, international, randomized clinical trial compared the risks and benefits of continued thienopyridine (clopidogrel or prasugrel) versus placebo, when given in addition to aspirin for the prevention of stent thrombosis or MACCE following coronary stenting with either DES or BMS in patients who tolerated DAPT to 12 months (ClinicalTrials.gov # NCT00977938). The results comparing randomized treatments in the DES-treated cohort have been reported separately.4

All institutions received approval from their Institutional Review Boards and each patient provided written informed consent for study participation.

Study Population and Procedures

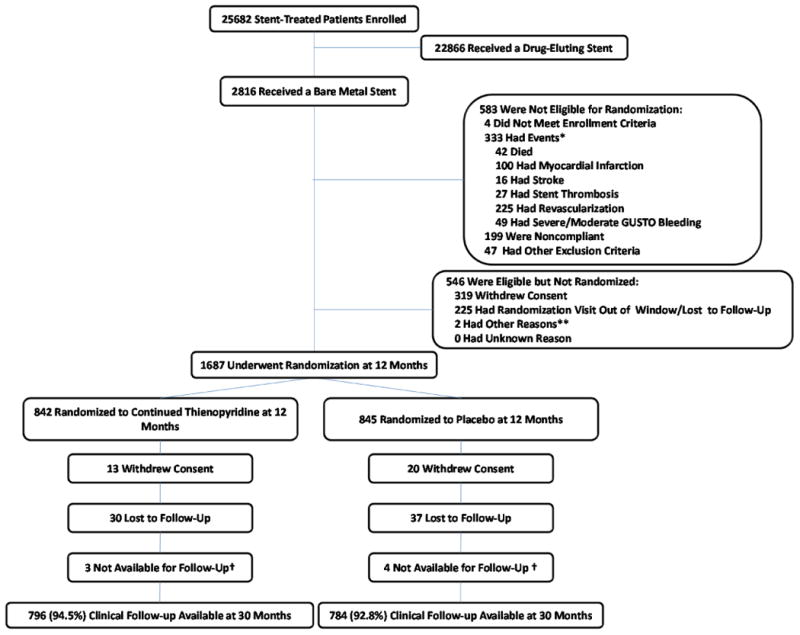

In brief, patients who were candidates for DAPT and who received treatment with either DES or BMS were recruited. Stent treatment was performed according to site standards of care using only Food and Drug Administration-approved DES and BMS devices. DES types included Cypher sirolimus-eluting stent (Cordis, Warren, NJ), Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent (Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA), TAXUS paclitaxel-eluting stent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA), and Xience/Promus everolimus-eluting stents (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA or Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). All patients >18 years of age who met all enrollment inclusion and none of the exclusion criteria (Appendix Table 2), and signed the consent and were enrolled into the trial within 3 days of the index procedure and all received open-label aspirin plus thienopyridine for the first 12 months. As required by regulatory authorities, race and ethnicity data were collected via patient self-report. Race categories for this study were pre-specified as America Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White and Other, specify. Ethnicity was collected as Hispanic or Latino and Not Hispanic or Latino. At 12 months, patients who were alive and free from MI, stroke, repeat coronary revascularization, stent thrombosis, and moderate or severe bleeding and who demonstrated compliance with thienopyridine treatment were then eligible for randomization (Figure 1) to continued thienopyridine or placebo, and all continued aspirin. A computer-generated randomization schedule stratified patients according to the type of stent they had received (drug eluting vs. bare metal), hospital site, thienopyridine type, and presence or absence of at least one prespecified clinical- or lesion-related risk factor for stent thrombosis (see Appendix Table 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up Among Randomized Bare Metal Stent-Treated Patients.

Post-randomization study procedures and follow-up were the same for BMS- and DES-treated patients.

Study Endpoints

The co-primary effectiveness end points were cumulative incidence of definite/probable stent thrombosis according to the Academic Research Consortium classification9 and incidence of MACCE at 12-30 months. For randomized comparison of DAPT duration among BMS-treated patients, the primary safety endpoint was moderate or severe bleeding (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries [GUSTO] classification)10 at 12-30 months. Finally, clinically actionable non-coronary artery bypass graft related bleeding was also evaluated according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium definitions (BARC 2, 3 or 5 classes).11 These events were adjudicated by an independent Clinical Events Committee blinded to treatment assignment and administered by HCRI. An unblinded independent central data monitoring committee oversaw the safety of all patients.

Statistical Analysis

Among patients treated with BMS and randomized to continued thienopyridine vs. placebo, the cumulative incidence of stent thrombosis and of MACCE are presented according to intention-to-treat. Treatments were compared using a log-rank test stratified by geographic region (North America, Europe, and Australia/New Zealand), thienopyridine type, and presence/absence of stent thrombosis risk factors (listed in Table 1).8 For each endpoint, the stratified hazard ratio (HR) and its 2-sided 95% CI comparing continued thienopyridine vs. placebo are presented. Patients not experiencing the co-primary endpoints 12-30 months post-index procedure were censored at the time of last known contact or 30 months, whichever was earlier.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Bare Metal Stent-Treated Patients.*

| Characteristics | Continued Thienopyridine N=842 |

Placebo N=845 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| % (N) reported for non-continuous variable | ||

| Patients | ||

| Age (years), mean ±SD | 58.9 ±10.5 | 59.2 ±11.1 |

| Female | 25.5% (215) | 21.8% (184) |

| Race- non-White** | 7.5% (62) | 7.3% (61) |

| Weight (kg), mean ±SD | 88.0 ±18.4 | 88.5 ±18.8 |

| BMI(Kg/m2), mean ±SD | 29.5 ±5.2 | 29.6 ±5.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21.7% (181) | 20.7% (173) |

| Hypertension | 64.0% (534) | 64.6% (543) |

| Cigarette smoker | 43.3% (360) | 43.3% (350) |

| Stroke/TIA | 5.1% (43) | 4.0% (34) |

| Congestive heart failure | 4.2% (35) | 3.3% (28) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4.2% (35) | 5.5% (46) |

| Prior PCI | 17.9% (150) | 20.3% (171) |

| Prior CABG | 6.0% (50) | 5.9% (50) |

| Prior MI | 19.4% (160) | 21.5% (178) |

| Indication for PCI | 58.8% | 58.3% |

| ACS | 58.8% (495) | 58.3% (493) |

| STEMI | 36.9% (311) | 38.3% (324) |

| NSTEMI | 21.9% (184) | 20.0% (169) |

| Unstable Angina*** | 9.1% (77) | 9.6% (81) |

| Stable Angina | 23.6% (199) | 23.4% (198) |

| Other | 8.4% (71) | 8.6% (73) |

| Any risk factor for stent thrombosis | 69.2% (568) | 69.0% (569) |

| Any Clinical | 64.0% (525) | 63.2% (521) |

| Enzyme positive ACS (STEMI or NSTEMI) | 58.8% (495) | 58.3% (493) |

| Renal insufficiency/failure | 3.4% (28) | 2.4% (20) |

| LVEF < 30% | 4.0% (32) | 3.6% (29) |

| Any Lesion-Related | 38.7% (325) | 37.5% (316) |

| > 2 vessels stented | 0.0% (0) | 0.1% (1) |

| > 2 lesions per vessel | 1.1% (9) | 1.0% (8) |

| Lesion length ≥ 30 mm | 6.5% (55) | 6.6% (56) |

| Bifurcation lesion sidebranch ≥ 2.5 mm | 4.5% (38) | 4.0% (34) |

| In-stent restenosis of a DES | 0.4% (3) | 0.7% (6) |

| Vein bypass graft stented | 2.6% (22) | 2.4% (20) |

| Unprotected left main stented | 0.0% (0) | 0.1% (1) |

| Thrombus-containing lesion | 28.9% (243) | 25.9% (219) |

| Prior Brachytherapy | 0.1% (1) | 0.1% (1) |

| Region | ||

| North America | 60.5% (509) | 61.4% (519) |

| Europe | 36.1% (304) | 35.5% (300) |

| Australia or New Zealand | 3.4% (29) | 3.1% (26) |

| Thienopyridine drug at randomization | ||

| Clopidogrel | 86.7% (730) | 86.6% (732) |

| Prasugrel | 13.3% (112) | 13.4% (113) |

| Number of treated lesions, mean ±SD | 1.2 ±0.4 | 1.12 ±0.4 |

| Number of treated vessels, mean ±SD | 1.0 ±0.2 | 1.1 ±0.2 |

| Number of stents, mean ±SD | 1.3 ±0.6 | 1.3 ±0.6 |

| Minimum stent diameter (per subject) | ||

| <3 | 23.9% (201) | 24.4% (206) |

| ≥3 | 76.1% (641) | 75.6% (639) |

| Total stent length (mm), mean ±SD | 24.0 ±13.0 | 23.9 ±13.1 |

| Lesions† | ||

| Treated Vessel | ||

| Left main | 0.0% (0) | 0.1% (1) |

| LAD | 31.6% (308) | 30.9% (306) |

| Right | 44.8% (437) | 45.6% (452) |

| Circumflex | 21.1% (206) | 20.9% (207) |

| Venous graft | 2.5% (24) | 2.5% (25) |

| Arterial graft | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) |

| Modified ACC/AHA lesion class B2 or C | 47.6% (440) | 47.8% (450) |

Abbreviations: ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AHA, American Heart Association; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DES, drug-eluting stent; LAD, left anterior descending; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation MI; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation MI; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

For all variables, 0-4% of subjects had missing values.

Race was self-reported.

This category included unstable angina without reported elevation of cardiac enzymes.

A total of 975 lesions were treated in the continued thienopyridine group and 991 in the placebo group.

The definitions of class B2 and class C lesions according to the modified American College of Cardiology (ACC)–American Heart Association (AHA) criteria.23

The analysis of the BMS cohort comparing randomized treatment arms was a prespecified secondary analysis of the DAPT Study that was not powered to compare treatment arms within this cohort (the powered DES-treated cohort has been previously presented4) but was performed to assess consistency of the randomized treatment effect in BMS- vs. DES-treated patients from the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study. Stent-type-by-randomized treatment interaction was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression as a post hoc analysis, and the stratified HR, 95% CI, and P values for interaction are presented. All other analyses presented were prespecified.

All statistical analyses were conducted at HCRI with SAS software, version 9.2. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All p-values are two-sided and considered significant at the 0.05 level.

Results

Study Population

Enrollment in the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study was conducted between August 2009 and July 2011, with the last follow-up visit conducted in May 2014. Of 2816 enrolled BMS-treated patients, 583 (20.7%) were not eligible for randomization after 12 months of follow-up, 546 (19.4%) were eligible but not randomized, and 1687 (59.9%) were randomized (Figure 1). Of 25682 total enrolled patients, 5844 (22.8%) were not eligible for randomization after 12 months of follow-up, 8190 (31.9%) were eligible but not randomized, and 11648 (45.4%) were randomized, with median follow up of 990 days (25% Q1: 981 days; 75% Q2: 990 days) (Appendix Figure 1). The most common reason for non-randomization was withdrawal of patient consent.

Baseline characteristics of BMS-treated randomized patients were similar between the groups (Table 1). While the same inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to all enrolled patients, DES- and BMS-treated patients differed according to clinical and procedural characteristics (Appendix Table 1). DES-treated patients were more likely to have a history of diabetes mellitus (30.6% vs. 21.2%, P<0.001), hypertension, previous PCI, and to have longer lesions, with smaller reference vessel diameter, while BMS-treated patients were more likely to present with ST-elevation MI (STEMI, 37.6% vs. 10.5%, P<0.001), or non-STEMI (20.9% vs. 15.5%, P<0.001), and were more likely to have thrombus noted in the treated lesion. The baseline characteristics of the randomized, DES-treated patients have been previously published.4 Baseline characteristics of all randomized patients were similar between the randomly assigned treatment groups (Appendix Table 1). Predefined risk factors for stent thrombosis were present in 54% of patients in each randomly assigned treatment group.

Effect of Continued Thienopyridine Therapy Among BMS–Treated Patients

Within randomized BMS-treated patients, the cumulative incidence of stent thrombosis and MACCE were 0.5% vs. 1.1% (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.15-1.64, log-rank P=0.24) and 4.0% vs. 4.7% (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.57-1.47, log-rank P=0.72), respectively, for continued thienopyridine vs. placebo at 12-30 months after the index procedure (Table 2). GUSTO severe/moderate bleeding events occurred in 2.03% vs. 0.90% among BMS-treated patients randomized to continued thienopyridine vs. placebo (P=0.07); and BARC 2, 3, or 5 bleeding events occurred in 4.56% vs. 1.80% respectively (P=0.002). Severe bleeding was uncommon and fatal bleeding events (BARC 5) were rare and not different between treatment groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Ischemic and Bleeding Outcomes In Randomized Bare Metal Stent-Treated Patients.

Patients were randomized to continued thienopyridine or placebo plus aspirin 12 months after receiving a bare metal stent. The effectiveness endpoints, stent thrombosis and MACCE, are shown over the primary analysis period, e.g. 12-30 months after enrollment. For the safety endpoint of GUSTO severe or moderate bleeding, patients whose last contact date was ≥ 510 days post randomization or who experienced any adjudicated bleeding outcome at or before 540 days were included.

| Continued Thienopyridine N=8421 |

Placebo N=8451 |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Log-rank P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Ischemic Outcomes | No. of patients (%) | |||

| Stent thrombosis* | 4 (0.50) | 9 (1.11) | 0.49 (0.15, 1.64) | 0.24 |

| Definite | 4 (0.50) | 9 (1.11) | 0.49 (0.15, 1.64) | 0.24 |

| Probable | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | N/A | . |

| MACCE (death, MI, stroke) | 33 (4.04) | 38 (4.69) | 0.92 (0.57, 1.47) | 0.72 |

| Death, all cause | 8 (0.99) | 10 (1.24) | 0.90 (0.35, 2.33) | 0.83 |

| MI | 22 (2.70) | 25 (3.10) | 0.91 (0.51, 1.62) | 0.74 |

| Stent thrombosis-related | 4 (0.50) | 9 (1.11) | 0.49 (0.15, 1.64) | 0.24 |

| Non stent thrombosis-related | 18 (2.21) | 16 (1.99) | 1.12 (0.57, 2.20) | 0.74 |

| Stroke (total) | 6 (0.73) | 5 (0.62) | 1.22 (0.37, 4.01) | 0.74 |

| Ischemic | 4 (0.49) | 5 (0.62) | 0.82 (0.22, 3.05) | 0.77 |

| Hemorrhagic | 1 (0.12) | 0 (0.00) | N/A | 0.32 |

| Type Uncertain | 1 (0.12) | 0 (0.00) | N/A | 0.32 |

| Bleeding Complications** | Continued Thienopyridine N=790 |

Placebo N=776 |

Risk Difference | 2-Sided P Value for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. of patients (%) | Percentage points (95% CI) | |||

| GUSTO Severe/Moderate | 16 (2.03) | 7 (0.90) | 1.12% (-0.06%,2.31%) | 0.07 |

| GUSTO Severe | 6 (0.76) | 3 (0.39) | 0.37% (-0.37%,1.12%) | 0.33 |

| GUSTO Moderate | 10 (1.27) | 4 (0.52) | 0.75%(-0.18%,1.68%) | 0.12 |

| BARC Types 2, 3, or 5 | 36 (4.56) | 14 (1.80) | 2.75% (1.02%,4.48%) | 0.002 |

| BARC Type 2 | 22 (2.78) | 7 (0.90) | 1.88% (0.56%,3.21%) | 0.01 |

| BARC Type 3 | 16 (2.03) | 6 (0.77) | 1.25% (0.09%,2.41%) | 0.04 |

| BARC Type 5 | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.13) | -0.13% (-0.38%,0.12%) | 0.31 |

Abbreviations: ARC, Academic Research Consortium; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction.

Please see Supplementary Appendix: Table 3 for GUSTO and BARC definitions.

Definite and probable stent thrombosis were determined according to the criteria of the Academic Research Consortium.

The primary safety end point was moderate or severe bleeding as assessed according to GUSTO criteria. Only patients who could be evaluated were included in this analysis (i.e., patients whose last contact date was ≥510 days after randomization or who had any adjudicated bleeding event at or before 540 days). Patients could have had more than one bleeding episode. The secondary analysis of bleeding is assessed according to the criteria of the BARC criteria.

Percentages are Kaplan-Meier estimates.

The results comparing continued thienopyridine vs. placebo in the DES-treated cohort have been reported previously and demonstrated significant reductions in study co-primary endpoints of stent thrombosis (0.4% vs. 1.4%, respectively, HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.17-0.48) and MACCE (2.0% vs. 1.5%, respectively, HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.59-0.85) (driven by a reduction in both stent and non-stent related MI, Table 3). An increase in moderate/severe bleeding events was observed (2.5% vs. 1.6%, respectively, P=0.001), and a difference in all-cause mortality rate that was not statistically significant was seen 2.0% vs. 1.5% (p=0.052), yet mortality was infrequently related to bleeding (0.1% vs. 0.1% fatal bleeding, P=0.38, and 0.22% vs. 0.06% bleeding-related mortality, p=0.57).1

Table 3. Treatment Interaction by Stent Type on Outcomes.

Analyses of treatment interaction by stent type, shown with Kaplan-Meier event rates, hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for efficacy and safety outcomes at 12-30 months among all randomized patients (9961 drug-eluting stent-treated and 1687 bare metal stent-treated).

| Continued Thienopyridine N (%) |

Placebo N (%) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value for Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. of patients (%) | ||||

| Definite or Probable Stent Thrombosis* | 0.42 | |||

| DES | 19 (0.4) | 65 (1.4) | 0.29 (0.17,0.48) | |

| BMS | 4 (0.5) | 9 (1.1) | 0.49 (0.15,1.64) | |

| MACCE | 0.32 | |||

| DES | 211 (4.3) | 285 (5.9) | 0.71 (0.59,0.85) | |

| BMS | 33 (4.0) | 38 (4.7) | 0.92 (0.57,1.47) | |

| Death | 0.41 | |||

| DES | 98 (2.0) | 74 (1.5) | 1.36 (1.00,1.85) | |

| BMS | 8 (1.0) | 10 (1.2) | 0.90 (0.35,2.33) | |

| GUSTO Severe/Moderate Bleeding | 0.30 | |||

| DES | 119 (2.5) | 73 (1.5) | 1.60 (1.19,2.17) | |

| BMS | 16 (1.9) | 7 (0.9) | 2.74 (1.05,7.00) | |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0.04 | |||

| DES | 99 (2.1) | 198 (4.1) | 0.47 (0.37,0.61) | |

| BMS | 22 (2.7) | 25 (3.1) | 0.91 (0.51,1.62) | |

Abbreviations: BMS, bare metal stents; DES, drug-eluting stents; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

Definite and probable stent thrombosis were determined according to the criteria of the Academic Research Consortium.

Consistency of Effects of Continued Thienopyridine Across BMS- and DES-Treated Patients

The post hoc analysis of the effect of continued thienopyridine found non-significant interactions between randomized BMS- and DES-treated patients for both stent thrombosis (interaction P=0.42) and MACCE (interaction P=0.32, Table 3).

Among all randomized patients, the co-primary effectiveness endpoints of stent thrombosis (0.41% vs. 1.32%; HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.19-0.50; P<0.001) and MACCE (4.29% vs. 5.74%; HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62-0.87; P<0.001) were reduced by continued thienopyridine versus placebo, respectively (Table 4). The reduction in stent thrombosis was largely explained by a reduction in definite stent thrombosis and the reduction in MACCE was largely explained by a 48% relative reduction (1.83% absolute) in MI. Significant reductions in MI related to stent thrombosis (0.38% vs. 1.28%, HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.18-0.48; P<0.001) as well as MI not related to stent thrombosis (1.84% vs. 2.75%, HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.50-0.84; P<0.001) were observed. In contrast, there is an increased incidence of severe/moderate bleeding events (2.45% vs. 1.47%, risk difference 0.98, 95% CI 0.46-1.50; P<0.001) largely explained by the relative increase in moderate bleeding (1.65% vs. 0.96%, risk difference 0.70, 95% CI 0.27-1.12; P=0.001). Similarly, although BARC Types 2, 3, or 5 bleeding events were significantly increased in the continued thienopyridine treatment group (5.44% vs. 2.78%, HR 2.65, 95% CI 1.91-3.40; P<0.001), fatal (Type 5) BARC bleeding events were rare and not different between groups (0.13% vs. 0.09%, HR 0.04, 95% CI -0.09 to 0.16; p=0.58; Table 4).

Table 4.

Ischemic and Bleeding Outcomes in All (Bare Metal and Drug-eluting Stent-Treated) Randomized Patients Comparing Continued Thienopyridine vs Placebo.

| Outcome | Continued Thienopyridine N=58621 |

Placebo N=57861 |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Log-rank P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. of patients (%) | ||||

| Stent thrombosis* | 23 (0.41) | 74 (1.32) | 0.31 (0.19, 0.50) | <.001 |

| Definite | 19 (0.34) | 67 (1.20) | 0.28 (0.17, 0.47) | <.001 |

| Probable | 5 (0.09) | 7 (0.12) | 0.71 (0.23, 2.24) | 0.56 |

| MACCE (Death, MI, Stroke) | 244 (4.29) | 323 (5.74) | 0.73 (0.62, 0.87) | <.001 |

| Death, all cause | 106 (1.87) | 84 (1.50) | 1.31 (0.97, 1.75) | 0.07 |

| MI | 121 (2.15) | 223 (3.98) | 0.52 (0.42, 0.65) | <.001 |

| Stent thrombosis-related | 21 (0.38) | 72 (1.28) | 0.29 (0.18, 0.48) | <.001 |

| Non stent thrombosis-related | 104 (1.84) | 154 (2.75) | 0.65 (0.50, 0.84) | <.001 |

| Stroke (total) | 43 (0.76) | 48 (0.86) | 0.84 (0.55, 1.28) | 0.42 |

| Ischemic | 28 (0.50) | 39 (0.70) | 0.70 (0.43, 1.15) | 0.16 |

| Hemorrhagic | 14 (0.25) | 9 (0.16) | 1.31 (0.55, 3.12) | 0.53 |

| Type uncertain | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.02) | 1.01 (0.06, 16.09) | 1.00 |

| Bleeding Complications** | Continued Thienopyridine N=5500 |

Placebo N=5425 |

Difference | Two-sided P Value for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. of patients (%) | Percentage points (95% CI) | |||

| GUSTO Severe/Moderate | 135 (2.45) | 80 (1.47) | 0.98 (0.46, 1.50) | <.001 |

| GUSTO Severe | 44 (0.80) | 29 (0.53) | 0.27 (-0.04, 0.57) | 0.09 |

| GUSTO Moderate | 91 (1.65) | 52 (0.96) | 0.70 (0.27, 1.12) | 0.001 |

| BARC Types 2, 3, or 5 | 299 (5.44) | 151 (2.78) | 2.65 (1.91, 3.40) | <.001 |

| BARC Type 2 | 167 (3.04) | 79 (1.46) | 1.58 (1.03, 2.13) | <.001 |

| BARC Type 3 | 138 (2.51) | 74 (1.36) | 1.15 (0.63, 1.66) | <.001 |

| BARC Type 5 | 7 (0.13) | 5 (0.09) | 0.04 (-0.09, 0.16) | 0.58 |

Abbreviations: BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries, MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction.

Definite and probable stent thrombosis were determined according to the criteria of the Academic Research Consortium.

Percentages are Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Results for MACCE and stent thrombosis are for all randomized patients; patients not experiencing the endpoint are censored at 30 months or at last known follow-up, whichever is earlier.

Only patients who could be evaluated were included in this analysis (i.e., patients whose last contact date was ≥510 days after randomization or who had any adjudicated bleeding event at or before 540 days). Patients could have had more than one bleeding episode.

Discussion

Among patients undergoing coronary stenting with BMS and who tolerated 12 months of thienopyridine, continuing thienopyridine for an additional 18 months compared to placebo did not result in statistically significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis, MACCE, or moderate/severe bleeding. However, limitations in sample size and power make definitive conclusions regarding DAPT treatment duration effects difficult. While fewer BMS-treated patients were enrolled and randomized because of the prevailing use of DES in clinical practice, among patients eligible for continued DAPT, in a post hoc analysis we found non-significant interactions for the effect of continued thienopyridine therapy on stent thrombosis among BMS- and DES-treated patients who were randomized in the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study.4 However, as this comparison of treatment interaction was not adequately powered for definitive interpretations, true differences in treatment effect size may not have been detected and the observation that continued thienopyridine therapy beyond one year (in patients who tolerated DAPT for one year without major bleeding) may prevent ischemic events independent of stent type (DES or BMS) should be considered hypothesis-generating.

Indeed, BMS-treated patients accrue target lesion (stent) related events in ≥2% per year12 and non-target lesion/vessel events in ≥5% per year following stent deployment.13,14 Late atherothrombotic events following BMS may be due to lack of healing/uncovered stent struts, neoatherosclerosis,15 restenosis,16 or disease progression outside the stent, in other regions or vessels. The largest portion of MI prevented by extended duration thienopyridine therapy in this study did not involve the stented coronary segments for either DES or BMS. While bleeding events were similarly increased with continued thienopyridine therapy beyond one year in both BMS and DES treated patients, these events were infrequently severe and rarely fatal (BARC 5 classification).11 The numeric increase in mortality associated with continued thienopyridine therapy (2.0 vs. 1.5%, p=0.052) that was observed in the DES-treated cohort, was not evident among BMS-treated randomized patients (1.0% vs. 1.2%, P=0.83).

The lack of apparent treatment interaction between DES and BMS supports the combined analysis of treatment effects of continued duration of therapy independent of stent type. Among the combined BMS and DES cohort, the reductions in stent thrombosis and MACCE were 69% and 27%, respectively in patients continuing thienopyridine therapy together with aspirin. 50% of the MIs prevented by continued DAPT were not stent thrombosis related. These ischemic event benefits were balanced by a 67% relative increase in moderate bleeding

Limitations

The major limitation of the BMS randomized comparison of DAPT duration is sample size and lack of power which limits the interpretability of the findings. However, an adequately powered randomized BMS cohort would require approximately 8,000 additional patients, which was practically not feasible under financial and logistic constraints of the study. An adequate number of BMS-treated patients were enrolled to allow a powered comparison of stent thrombosis and MACCE rates with patients treated with DES,17 the results of which have been presented separately.18 In this context, the design of the BMS randomized comparison was to evaluate for consistency or heterogeneity compared with the DES treatment effect in an exploratory fashion, rather than to be powered for a separate, independent analysis. Nonetheless, the BMS cohort sample size exceeds that of prior randomized BMS cohorts evaluating duration of antiplatelet therapy5 and is similar in size to many prior randomized trials of DAPT duration in DES.5,19-22 While similar inclusion criteria were required of BMS- and DES-treated patients, there were systematic differences between BMS- and DES-treated patients with a higher frequency of MI presentation prior to the index PCI procedure for BMS and a higher prevalence of restenosis risk factors for DES-treated patients. Nevertheless, each cohort was balanced across randomized treatment arms as expected according to the stratified randomization.

Conclusions

Among patients undergoing coronary stenting with BMS and who tolerate 12 months of thienopyridine and aspirin therapy without major bleeding, continuing thienopyridine therapy in addition to aspirin beyond 12 months, did not result in statistically significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis, MACCE or moderate/severe bleeding. However, the BMS subset may have been underpowered to determine such differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sponsored by Harvard Clinical Research Institute. Funded by Abbott, Boston Scientific Corporation, Cordis Corporation, Medtronic, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership, Eli Lilly and Company, and Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited and the US Department of Health and Human Services (1RO1FD003870-01).

Additional Contributions: We thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the DAPT Study for their valuable contributions. We wish to acknowledge Joanna Suomi, MSc, for assistance editing and formatting this manuscript, Wen-Hua Hsieh, PhD, for assistance with statistical analysis. Both Ms. Suomi and Ms. Hsieh are employed by Harvard Clinical Research Institute and were compensated for their contributions to this manuscript.

Funding: This research has been sponsored by Harvard Clinical Research Institute and funded by Abbott, Boston Scientific Corporation, Cordis Corporation, Medtronic, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership, Eli Lilly and Company, and Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited and the US Department of Health and Human Services (1RO1FD003870-01).

Role of the Sponsors: The funding manufacturers and FDA had input on the study design and conduct of the study. HCRI oversaw the collection, management, and analysis of the data; the study authors were responsible for interpretation of the data, preparation of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Dr. Yeh reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular, personal fees and non-financial support from Harvard Clinical Research Institute, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work. Dr. Massaro reports personal fees from Harvard Clinical Research Institute during the conduct of the study. Ms. Driscoll-Shempp has nothing to disclose. Dr. Cutlip reports other from Medtronic, other from Boston Scientific, other from Cordis Inc., other from Abbott Vascular, grants from NHLBI, during the conduct of the study Dr. Steg reports personal fees from Amarin, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol-Myers-Squibb, personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from Merck-Sharpe-Dohme, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Otsuka, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Medtronic, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, grants and personal fees from Servier, personal fees from Vivus, personal fees from The Medicines Company, personal fees from Orexigen, outside the submitted work. Dr. Gershlick reports personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Abbott, grants from Medicines Company, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Darius reports grants from Harvard Clinical Research Institute, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Meredith reports other from Boston Scientific, other from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. Dr. Ormiston has nothing to disclose. Dr. Tanguay reports personal fees and other from Abbott Vascular, personal fees and other from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees and other from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees and other from Eli Lilly, personal fees and other from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Roche, personal fees and other from Sanofi-Aventis, personal fees from Servier, other from Ikaria, other from Merck, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Windecker reports grants from St Jude Medical, grants from Biotronik, grants from Medicines Company, grants from Abbott, grants from Medtronic, grants from Edwards Lifesciences, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Abbott, personal fees from Biosensors, personal fees from Biotronik, personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Garratt reports grants from Boston Scientific Corporation, personal fees from Boston Scientific Corporation, personal fees from The Medicines Company, grants from Abbott Vascular, personal fees from Abbott Vascular, grants from CeloNova, other from Infarct Reduction Technologies, Inc, other from Guided Delivery Systems, personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo/Lilly, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kandzari reports grants from Medtronic CardioVascular, grants from Abbott Vascular, grants from Boston Scientific, grants from Biotronik, personal fees from Micell Technologies, personal fees from Medtronic CardioVascular, personal fees from Boston Scientific, outside the submitted work. Dr. Lee reports grants from Boston Scientific, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Boston Scientific, personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. Dr. Simon reports other from Cordis/Johnson & Johnson, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Cordis/Johnson & Johnson, personal fees from Medtronic Vascular, outside the submitted work. Dr. Iancu has nothing to disclose. Dr. Tr ębacz has nothing to disclose. Dr. Mauri reports grants from Abbott, grants from Boston Scientific, grants from Medtronic, grants from Cordis, grants from Eli Lilly, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants from Sanofi-Aventis, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from St Jude, grants and personal fees from Biotronik, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs. Kereiakes and Mauri had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Design and conduct of the study: Kereiakes, Yeh, Massaro, Mauri

Collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data: Kereiakes, Yeh, Massaro, Mauri, Driscoll-Shempp

Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: Kereiakes, Yeh, Massaro, Mauri

Decision to submit the manuscript for publication: Kereiakes, Yeh, Mauri

Previous Presentation: Results were presented in an abstract and in a presentation at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions; Chicago, IL, November 18, 2014.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr. Kereiakes reports no conflicts of interest. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, et al. Twelve or 30 Months of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after Drug-Eluting Stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2155–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Monti M, et al. Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2015–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badheka A, Arora S, Panaich S, et al. Impact on In-Hospital Outcomes With Drug-Eluting Stents Versus Bare-Metal Stents (from 665,804 Procedures) Am J Cardiol. 2014 Dec 1;114(11):1629–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas PS, Brennan JM, Anstrom KJ, et al. Clinical effectiveness of coronary stents in elderly persons: results from 262,700 Medicare patients in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1629–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, et al. Rationale and design of the dual antiplatelet therapy study, a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial to assess the effectiveness and safety of 12 versus 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy in subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with either drug-eluting stent or bare metal stent placement for the treatment of coronary artery lesions. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1035–41. 41 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. The GUSTO investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:673–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309023291001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaji K, Kimura T, Morimoto T, et al. Very long-term (15 to 20 years) clinical and angiographic outcome after coronary bare metal stent implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:468–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.958249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutlip DE, Chhabra AG, Baim DS, et al. Beyond restenosis: five-year clinical outcomes from second-generation coronary stent trials. Circulation. 2004;110:1226–30. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140721.27004.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chacko R, Mulhearn M, Novack V, et al. Impact of target lesion and nontarget lesion cardiac events on 5-year clinical outcomes after sirolimus-eluting or bare-metal stenting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takano M, Yamamoto M, Mizuno K. Two cases of coronary stent thrombosis very late after bare-metal stenting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1286–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen MS, John JM, Chew DP, Lee DS, Ellis SG, Bhatt DL. Bare metal stent restenosis is not a benign clinical entity. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, Ho KK, D'Agostino R, Cutlip DE. Stent thrombosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1020–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Massaro JM, et al. Comparison of ischemic events after drug-eluting stents or bare metal stents in subjects receiving dual antiplatelet therapy: results from the randomized Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2113. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilard M, Barragan P, Noryani AA, et al. Six-month versus 24-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug eluting stents in patients non-resistant to aspirin: ITALIC, a randomized multicenter trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Nov 16; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.11.008. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Park KW, et al. Six-month versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents: the Efficacy of Xience/Promus Versus Cypher to Reduce Late Loss After Stenting (EXCELLENT) randomized, multicenter study. Circulation. 2012;125:505–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.059022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feres F, Costa RA, Abizaid A, et al. Three vs twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy after zotarolimus-eluting stents: the OPTIMIZE randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2510–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colombo A, Chieffo A, Frasheri A, et al. Second Generation Drug-Eluting Stents Implantation Followed by Six Versus Twelve-Month - Dual Antiplatelet Therapy- The SECURITY Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(20):2086–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellis SG, Vandormael MG, Cowley MJ, et al. Coronary morphologic and clinical determinants of procedural outcome with angioplasty for multivessel coronary disease. Implications for patient selection. Multivessel Angioplasty Prognosis Study Group. Circulation. 1990;82:1193–202. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.