Abstract

There are several choices of cells to use for cartilage repair. Cells are used as internal or external sources and sometimes in combination. In this article, an analysis of the different cell choices and their use and potential is provided. Embryonic cartilage formation is of importance when finding more about how to be able to perfect cartilage repair. Some suggestions for near future research based on up-to-date knowledge on chondrogenic cells are given to hopefully stimulate more studies on the final goal of cartilage regeneration.

Keywords: chondrogenic, chondrocytes, stem cells

Introduction

It is quite common to talk about cellular and acellular approaches for tissue repair. However, to repair damaged tissue with biological means, cells are always needed. Even if one uses artificial plastic or metal implants, cells are needed for integration to the surrounding tissue. When discussing acellular approaches, one mostly refers to the use of porous scaffolds or injections of growth factors or a combination of these to attract intrinsic cells to migrate into the injured area, while cellular approaches involve the extrinsic manipulation of cells and subsequent implantation. In this article, I will discuss and evaluate those 2 types of approaches, perhaps better described as the intrinsic or extrinsic use of cells for cartilage repair.

Cartilage and Cartilage Repair

Cartilage has a poor reparative capacity,1 and it is unclear as to what extent this may be dependent on age or maturation. Tew et al.2 looked at the cellular responses of chondrocytes to experimental wounds in vitro using 3 maturation states of cartilage:

embryonic cartilage,

immature cartilage, and

mature cartilage.

In all cases, the trauma response was consistent, showing a combination of cell death that included apoptosis and proliferation.2 The speed of reaction to the trauma varied in terms of the degree of cell death. Embryonic cartilage showed the fastest response, while mature cartilage showed the slowest response. The degree of intrinsic repair as evaluated by the ability to repair the lesion was not detected in any of the culture systems used. It was concluded that the poor repair potential of cartilage is not maturation dependent in the systems studied.2 This model was just to show the tissue-specific maturation possibilities. When looking at different cells and their chondrogenic capacity, there is an age-dependent decline in the chondrogenic ability by increasing age that is related to both chondrocytes and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) of varied origins.3

The Cell

The cell is the functional basic unit of life. The word “cell” comes from the Latin cellula, which means a small room, as described by Robert Hooke in 1665 when comparing cork cells that he saw through his microscope to the small rooms in which monks lived.4,5

All tissues consist of living cells, and damaged tissue needs cells to be restored. When cartilage lesions develop, they can be either traumatic or pathological such as due to osteoarthritis.6 They may be confined to the avascular layer of articular cartilage (partial-thickness defects) or may penetrate into subchondral bone (full-thickness defects). Partial-thickness defects show little spontaneous attempts of repair activity, whereas full-thickness defects have more or less strong repair activity. When subchondral bone is involved, 2 different types of tissue need to be repaired:

subchondral bone including the bone plate, the vascularized area; and

the cartilage part, the nonvascularized area.

Those 2 areas must be restored if joint function is to be maximally repaired. Cartilage has a very low number of cells and lacks blood vessels. Within the cartilage matrix, cell recruitment is subsequently not possible via vessel support as is seen in other tissue.7 Repair cells need to be recruited internally from a direct internal source, bone marrow derived, or externally handled or externally manipulated.

The cells of interest could be divided into 4 subgroups:

true committed autologous chondrocytes,

true committed allograft chondrocytes,

chondrogenic autologous progenitor cells, and

chondrogenic allograft progenitor cells.

Furthermore, the cells could be used as the following:

free cells in suspension as in first-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI),8

cells in scaffolds such as immature grafts as in third-generation ACI,9

fully developed mature grafts such as chondral- or osteochondral-like mosaic plugs10 and

cells on carriers such as in cell-seeded matrix-induced ACI.11

Acellular approaches aim to facilitate the repair activity of native cell populations. They may consist of an empty matrix or a matrix containing biological signaling agents that will recruit and trigger the differentiation of local stem cell populations, resulting in the formation of functional repair tissue.

Cell-Seeding Layers

When repairing a cartilage defect, one needs to look at the different layers of cartilage from the superficial layer through the intermediate and radiate layers down to the calcified layer and finally to bone. More and more researchers have found that to become successful in cartilage tissue engineering, one needs to recapitulate the 5 folding layers of native cartilage.7 A gradient of time-sequential incoming signals may get the different cells to align and behave as real native cartilage cells.

Even though cells migrate to different sites within a defect, cells have spatial awareness and have different missions within the layers. As will be discussed, also within the cartilage layers, the cells’ initial origin vary, and we do not know much about the signaling capacities, that is, cross-talking between the different cell types. Different cell types may need different 3-dimensional (3D) milieus for good positioning and function. Jeon et al.12 discussed the use of monophasic, biphasic, and triphasic scaffolds based on the biochemical and physical characteristics of the matrices used. They suggested that by designing osteochondral scaffolds with a tissue-specific architecture, it may be possible to enhance osteochondral repair within a shorter time frame.12 Shimomura et al.13 also discussed thoroughly the use of tissue-engineered biphasic scaffolds for osteochondral repair, which can mimic the native osteochondral complex. I agree that it is important to understand the process from the bone area via the calcified zone into pure cartilaginous tissue to one day be able to restore a cartilage defect by regeneration.

Chondrogenic Cell Choice

Culture-expanded chondrocytes have the potential to form cartilage in pellet mass cultures, to form adipose cells in dense monolayer cultures, and to form a calcium-rich matrix in an osteogenic assay. However, in contrast to MSCs, chondrocytes form cartilage only (and not bone) in an in vivo osteochondrogenic assay, as shown by Tallheden et al.14 Furthermore, Karlsson et al.15 looked at articular chondrocytes and iliac crest–derived MSCs from the same patients that were allowed to differentiate in pellet mass cultures. A significantly decreased expression of collagen type I was accompanied by the increased expression of collagen types IIA and IIB during the differentiation of chondrocytes, indicating differentiation towards a hyaline phenotype.15 Chondrogenesis in MSCs, on the other hand, resulted in the up-regulation of collagen types I, IIA, IIB, and X, demonstrating differentiation towards cartilage of a mixed phenotype.15 The results from this study suggest that chondrocytes and MSCs differentiate and form different subtypes of cartilage: a hyaline and a mixed cartilage phenotype, respectively.15

MSCs seem subsequently not to be able to fully become real chondrocytes, even though they produce a cartilage matrix. Such a subtype of cartilage may, however, be enough for the patient to induce functional repair tissue. In the literature, clinically, there are reports that results after bone marrow stimulation of cartilage defects decline after a certain time of >18 months,16,17 and it is seen most often between years 2 to 5 after surgery.18 Such a durability weakness needs to be further evaluated. Interestingly, when bone marrow stimulation techniques are studied in randomized trials, durability seems often equal with the other studied technique and with long-term durability.

However, Engen et al.19 found that results from published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in cartilage repair studies may not be representative for the gross cartilage population due to the heterogeneity of referred cartilage patients and the variation in inclusion criteria in the RCTs. Engen et al.19 concluded that one may question whether the available RCTs actually represent general cartilage patients.

What about the use of MSCs for cartilage repair purposes? Bone marrow stimulation techniques, being intrinsic repairs, are based on the ingrowth of MSCs from bone marrow, described to have a chondrogenic potential. However, MSCs, even after being oriented into a given chondrogenic pathway, need an additional stimulus by TGF-β2 to maintain their phenotype and metabolic activity.20 There subsequently is MSC phenotypic instability regarding the ability to remain in a chondrogenic state as described above: MSCs’ production of a final mixed type of hyaline cartilage.15

Furthermore, Pelttari and colleagues21 pointed out clearly that a persistent level of procollagen type IIA mRNA and an elevated level of COL10A1 mRNA with the continuous treatment of TGF-β2 raise concerns over the suitability of MSCs as a cell source for cartilage repair, showing the expression of type X collagen in an early period of a chondrogenic pellet culture. Some factors that promote chondrogenesis while inhibiting hypertrophic changes from MSCs should be necessary for cartilage engineering from MSCs.

Farrell et al.22 recently found that in the presence of TGF-β, chondrocytes outperformed MSCs through day 56 under both free swelling and dynamic culture conditions, with juvenile bovine MSC-laden constructs reaching a plateau in mechanical properties between days 28 and 56. Extending cultures through day 112 revealed that MSCs not only experienced a lag in chondrogenesis but also that constructs’ mechanical properties never matched those of chondrocyte-produced constructs. After 56 days, MSC-produced constructs underwent a marked reversal in their growth development, with significant declines in glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content and mechanical properties.22

Based on the above described findings, one may say that even within a controlled in vitro environment that is conducive for MSCs to go into chondrogenesis, there may be inborn instability in the MSC phenotype that is independent of scaffold composition and may ultimately limit their application in functional cartilage repair. True committed chondrocytes still seem to be the first choice when performing cartilage resurfacing.

Vinardell and collegues23 compared the in vitro functionality and in vivo phenotypic stability of cartilaginous tissue engineered using bone marrow–derived stem cells (BMSCs) and joint tissue–derived stem cells following encapsulation in agarose hydrogels. Culture-expanded BMSCs, fat pad–derived stem cells (FPSCs), and synovial membrane–derived stem cells (SDSCs) were encapsulated in agarose and maintained in a chondrogenic medium supplemented with TGF-β3.23 After 3 weeks of culture, constructs were either implanted subcutaneously into the back of nude mice for an additional 4 weeks or maintained for a similar period in vitro in chondrogenic or hypertrophic media formulations. After subcutaneous implantation in nude mice, sulfated GAG (sGAG) content significantly decreased for all stem cell–seeded constructs, while no significant change was observed in the control constructs engineered using primary chondrocytes, indicating that the in vitro chondrocyte-like phenotype generated in all stem cell–seeded agarose constructs was transient.23 FPSCs and SDSCs appeared to undergo fibrous dedifferentiation or resorption, as proven by increased collagen type I staining and a dramatic loss in sGAG content. BMSCs followed a more endochondral pathway with increased type X collagen expression and mineralization of the engineered tissue.23 Important to note is that in a vascularized environment such as subcutaneous tissue, MSCs lost their chondrogenic temporary status. It might have been different if those constructs had been placed in a partial-thickness defect with no connection to bone. However, most cartilage defects, when treated by debridement, have some connections to subchondral bone. Furthermore, when Carroll et al.24 seeded porcine BMSC and infrapatellar FPSC agarose hydrogels and cultured them in a chondrogenic medium simultaneously subjected to 10 MPa of cyclic hydrostatic pressure (HP), they found that HP enhanced the functional development of cartilaginous tissue. In addition, HP was found to suppress the calcification of tissue engineered using BMSCs cultured in chondrogenic conditions and acted to maintain a chondrogenic phenotype in cartilaginous grafts engineered using FPSCs.24

Biomechanically induced signals may then influence the phenotypic stability of MSCs. Clinically, most patients are allowed very little weightbearing after bone marrow stimulation for several weeks. Further research on the cyclic hydrostatic forces developed during weightbearing is subsequently needed to know about the early mechanical influences on the durability of at least bone marrow–based implants.

By using chondrocytes for the repair of cartilage lesions, the histology after repairs has mostly not been different compared to bone marrow stimulation repairs. At least, it has not been possible in most randomized series to discriminate between the repair tissue histology of different origins: another tissue (periosteum), a collagen scaffold, or a scaffold made from hyaluronan or something similar. Other living tissue or a dead collagen structure will influence the repair tissue composition. McCarthy and Roberts25 compared repair tissue formed by periosteum ACI with repair tissue from second-generation collagen-covered ACI. Compared with periosteum ACI, repair tissue formed in patients treated with collagen ACI demonstrated a significantly higher score for cellular morphology (International Cartilage Repair Society [ICRS] II score), significantly better surface morphology from medial femoral condyle–treated defects (ICRS II score), and a significantly higher proportion of hyaline cartilage formation.25 The collagen membrane is expected to be resolved with time, while the periosteum remains as part of the repair with a fibrous top layer, a transitional zone from cambium cells and chondrocytes, and finally as part of the repair from only chondrocytes. The cambium cells may have a trophic effect on the implanted chondrocytes, but they may also induce a subtype of cartilage compared to chondrocyte-produced cartilage.26 We need to remember that when combining different cells without the same chondrogenic capacity and with a different terminal differentiation fate related to the phenotype, the resulting repair tissue cannot be expected to become true cartilage but instead mixed tissue: fibrous-fibrocartilaginous.

Besides the use of BMSCs, stem cells from synovial tissues have attracted researchers’ interest. When using SDSCs, it is important to know that 2 subsets of SDSCs can be obtained from humans: fibrous SDSCs and adipose SDSCs.27 These 2 subsets of stem cells are differentiated by the underlying subsynovial connective tissue layer. Fibrous SDSCs can be obtained from areas with a fibrous subsynovial layer, while adipose SDSCs are found in areas with an adipose subsynovial layer.27 Mochizuki et al.27 have found that fibrous SDSCs seem to have more suitable properties for cartilage formation. Furthermore, when these 2 types of SDSCs were compared with adipose MSCs of a nonsynovial origin, both SDSC types were superior in their chondrogenic potential.27 Similar findings regarding the synovial cells were reported by Koga et al.28 when they isolated MSCs from the bone marrow, synovium, adipose tissue, and muscle of adult rabbits. MSCs from each tissue were implanted into a collagen gel and transplanted into full-thickness cartilage defects of rabbits.28 SDSCs and BMSCs had a greater in vivo chondrogenic potential than adipose and muscle MSCs, but SDSCs had the advantage of a greater proliferation potential.28 Shimomura et al.29 have shown that there is no skeletal maturity-dependent difference in the proliferation or chondrogenic differentiation capacity of porcine SDSCs.

Ultimate Clinical Chondrogenic Cells or Just In Vitro Testing Cells?

The terminal differentiation of different stem cells is a problem when using such cells for cartilage production purposes. Hellingman et al.30 showed that recently published methods for inhibiting terminal differentiation (through PTHrP, MMP13, or blocking phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8) result in cartilage formation with a reduction of hypertrophic markers. However, this manipulation is not enough for inhibition to reach a low level of stable chondrocytes. Interest has recently been focused more and more on the potential use of embryonic stem (ES) cells and induced pluripotent stem (IPS) cells, especially as clinically an increased demand for 1-stage cartilage repair products and techniques forced researchers to look for new alternatives of chondrogenic cells. Pluripotent stem cells derived from ES cells or reprogrammed cells can provide such a source. The fact that pluripotent stem cells could be derived from reprogrammed adult cells obtained from the same patient gives us a possible unlimited source of autologous pluripotent stem cells for such a patient. However, of interest to note is that Hiramatsu et al.31 performed direct reprogramming of chondrocytes from skin fibroblasts, as a potential new strategy to obtain chondrogenic cells, avoiding the need to produce IPS cells.

ES cells are derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst.32 The ability of ES cells to form cartilage is well known because they can form teratomas containing cartilage when they are transplanted into nude mice.32 However, when Gutierrez-Aranda et al.33 transplanted side by side as few as 1 × 106 of either fully characterized undifferentiated human ES cells or IPS cells in 6- to 8-week-old immune-deficient mice, they found that human IPS cells develop teratomas more efficiently and faster than human ES cells, regardless of the site of injection. Such findings raise concerns about using IPS cells for clinical cartilage repair purposes.33 Also, Uto et al.34 speculated that perhaps due to insufficient local factors reaching the transplanted IPS cells, there was a risk for an increase in the remaining undifferentiated cells to induce tumor formation. However, they were more optimistic and stated that perhaps IPS cells could be the dominant cell source in bone and cartilage regenerative medicine if cell selection and management were conducted properly and if the mechanical condition was in control after surgery.34 Their experiments were performed in mice, and a lot of research remains to find out the safe way to use human ES cells and IPS cells in the future.

Cells, Stability, and Scaffolds

Is it then possible to generate stable hyaline cartilage from adult MSCs? Hellingman et al.30 demonstrated that recently published methods for inhibiting terminal differentiation (through Prep, MMP13, or blocking phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8) result in cartilage formation with a reduction of hypertrophic markers, although this does not reach the low level of stable chondrocytes.

Inhibiting terminal differentiation may not result in stable hyaline cartilage if the right balance of signals has not been created from the start of culture onwards.30 Another way to stabilize the used cells is to use TGF-β stimulation within the first 3 days of culture, which seems to be crucial for the expression of a chondrogenic phenotype.35 Fully differentiated and encapsulated MSCs are not able to transdifferentiate into osteoblasts. These findings give rise to a better understanding of the behavior of cartilage grafts affected by local factors of osteochondral transplantation sites in vivo.35 Such a finding implicates that different scaffolds may have more or less a good ability to protect ingrowing cells from nonchondrogenic influences.

It is important for cells to be in a stable position, meaning that the 3D space and shape of the different scaffolds to be used are of high importance. However, different cells have different acquirements regarding porosities and attachment possibilities. Besides influencing the cells, the material should also allow soluble molecules to be able to enter and provide nutrition to cells. Finally, the scaffolds’ 3D structure controls the mechanical properties, going from no cells to invading cells without a matrix and finally to cells surrounded by their own matrix in a now degrading 3D temporary structure. Freed et al.36 reported that a porosity of at least 90% is needed to provide enough surface area for cell-scaffold interactions.

We quite quickly realize the difficulties in finding such an optimal scaffold for cells to develop into a chondrogenic phenotype and in the scaffold remain stable in the phenotype. Different biocompatible scaffolds assist subsequently in providing a template for cell distribution and extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation in 3D geometry.

A major challenge in choosing an appropriate scaffold for cartilage repair is the identification of a material that can simultaneously stimulate

high rates of cell division and

high rates of cell synthesis of phenotypically specific ECM macromolecules until repair tissue develops into final steady-state tissue.

The ideal scaffold/matrix is yet to be found. Different scaffolds of biological and synthetic origins have been used such as collagen I and II, fibrin gels, hyaluronic gels, decalcified bone, polyclycolic acids, ceramics, and carbon fiber meshworks. Most of them have been resorbable besides carbon fibers. Most often, chondrogenic cells are seeded onto the surface of the chosen scaffold after monolayer cell expansion in a week. However, some surgeons seed their cells just prior to introducing the cell-scaffold construct into the cartilage defect.37 Direct cell seeding might be less advisable, as there is a certain time for cells to attach to the matrix needed. Furthermore, if the scaffold after direct cell seeding is not temporarily covered with a protecting membrane, cells may be lost into the synovial joint cavity.

Kurtis et al.38 showed that following culture in a monolayer, the adhesion of chondrocytes to cartilage increased with time from 6% to 16% at 10 minutes to a maximum of 59% to 82% at 80 to 320 minutes. After 80 minutes of adhesion, the resistance of cells to flow-induced shear stress (50% detachment) was approximately 21 Pa.38 It was also shown that under the culture and seeding conditions studied, β1, α5β1, and αVβ5 integrins mediate human chondrocyte adhesion to cartilage.38 It is not known if adhesion on other surfaces such as from scaffolds involves other integrins.

Manolopoulos et al.39 found that after chondrocyte seeding to a cartilage surface, maximal adherence occurred by 24 hours after transplantation. Baseline transplant densities exceeding 1 × 106 cells/cm2 were observed on unmodified cartilage surfaces.39

In addition, no differences in chondrocyte adherence were noted in cells cultured in a monolayer or alginate beads. Of special interest was the finding that chondrocytes demonstrated significantly improved adherence to cartilage surfaces after the superficial layer was removed as compared to normal intact cartilage surfaces.

Wang and Kandel40 have shown that primary chondrocytes have a different shape, appearance of focal contacts, and actin distribution when compared to passaged cells, and these did not appear to be influenced by the type of surface to which the cells attached. Grigolo et al.41 found that when seeding chondrocytes on a hyaluronic scaffold, it takes 4 days after seeding until all of the HYAFF-11 fibers are completely covered by chondrocytes. Seven days after seeding, cells frequently exhibit bridging across different fibers of the substratum and wide overlapping of the membrane. Finally, at 14 days of growth, the 3D structure of HYAFF-11 is no longer recognizable, being entirely covered by flat and overlapped chondrocytes widely crossing the biomaterial fibers without interruption.41

Interestingly, Ionescu and Mauck42 found that the addition of expanded MSCs to scaffolds before in vitro repair improved the integration with native tissue but did not influence maturation. In contrast, preculture of these same scaffolds for 1 month before repair decreased the integration with native tissue but resulted in a more mature scaffold compared to the implantation of cellular scaffolds or acellular scaffolds.42

The Ultimate Cell-Induced Repair

Wnt-14 plays a role at the earliest step in the induction of the joint interzone, which later will be the articular joint.43 MSCs involved in joint formation are called interzonal cells.43 Those cells secrete Gdf5, which is a secreted signal necessary for joint formation produced in response to Wnt-14.44 Koyama et al.45 proposed that Gdf5-expressing joint progenitor cells are influenced to go into either a chondrogenic pathway or an antichondrogenic pathway. Via that action induced by members of the Gdf, Bmp, and Sox gene families, the cells become chondrogenic, and by further influence from factors such as Erg and TGF-β, the cells form articular cartilage.45 If instead those cells are influenced by Wnt and β-catenin, notch signaling, and Noggin, some cells would go into fibrogenic and mesodermal lineages, producing joint ligaments, synovia, and very important, the superficial cartilage layer.45 If instead chondrogenic cells are influenced from factors such as Erg and TGF-β, the cells form the rest of the articular cartilage.45 Those 2 different origins of the superficial cartilage and rest of the cartilage may be explained by the different influences as described above.

It is subsequently quite important to understand that articular chondrocytes and other joint cells derive from Gdf5-expressing interzonal cells. Contrary to this, shaft and growth plate cartilage derive from Gdf5-negative cells, likely representing the majority of the original mesenchymal condensation.45 What still remains unknown is how interzonal cells eventually escape the direct influence from Wnt-14 to undergo chondrogenesis and develop into committed articular chondrocytes.46 However, the Koyama dual pathway system45 may be used for clinical cartilage resurfacing purposes.

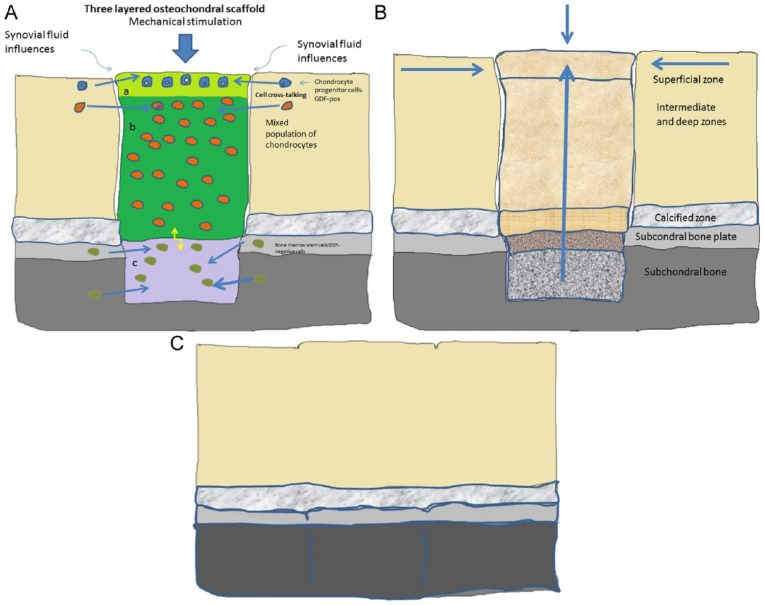

My vision on the future of cartilage tissue engineering is the use of 3-layered, seeded matrices for osteochondral repair (Fig. 1). To regenerate cartilage, the total layers of cartilage plus the bone region need to be reconstituted. One may start with isolation of the top layer of chondrocyte progenitor cells, followed by isolation of a separate deep layer of hypertrophic cells, and finally isolation of bone marrow cells for the osseous part. The different cell types are then seeded in 3 different layers in an appropriate matrix with the use of 3D printing methods. Another alternative is the use of only progenitor cells in the top layer seeded in the whole matrix but conducted in different layers with different growth factors (an example could be PTHrP) to induce the right cell gradient from bone to surface.47 It is important to develop the bone-cartilage transition zone: a unit of cartilage + subchondral bone, both depending on each other’s well-being. For the bone part of the gradient repair, MSCs are of interest to use. Shimomura et al.48 recently demonstrated restoration of the osteochondral junction by the hybrid implant of hydroxyapatite artificial bone and MSC-based tissue-engineered construct, which is a good example showing the advantage of using biphasic tissue-engineered constructs.

Figure 1.

(A) A multilayered scaffold with different cells in different layers, influenced by mechanical forces and cross-talking between the cells in the layers, the neighboring native cells, and signals from subchondral bone. (B) The cell-seeded scaffold has matured into osteochondral repair tissue, slowly being integrated into the defect area during the maturation process. (C) Total repair (almost regeneration).

Which origin for the MSCs should then be considered? Li et al.49 have shown that in a rabbit study with 6 groups treated by autogenic MSCs from bone marrow, periosteum, synovium, adipose tissue, and muscle, BMSCs produced much more cartilage matrices than other groups. In a 3-layered scaffold, one may expect cross-talking between the cells in the different layers, between the cells in the scaffold, and the native surrounding cells.50 Finally, with cross-talking between the seeded basal chondrocytes and BMSCs in the bottom layer positioned in subchondral bone, those combined cells may develop the calcified layer and the subchondral bone plate. Bian et al.51 have demonstrated that mixed cell populations (human MSCs and human chondrocytes at a ratio of 4:1), when encapsulated in hydrogels, exhibited significantly higher Young moduli, dynamic moduli, and GAG levels as well as collagen content than did constructs seeded with only MSCs or chondrocytes. Furthermore, the deposition of collagen X, a marker of MSC hypertrophy, was significantly lower in the coculture constructs than in the constructs seeded with MSCs alone.51 How to tune gradient tissue development with cells in the different layers is a major task for cartilage tissue engineering.

Conclusion

Today, external cellular technologies include laboratory isolation and in vitro expansion of cells. Cellular approaches could also involve the direct isolation of cells in the operating room, the use of crushed cartilage fragments in gels, and cells used either alone or in conjunction with smart matrices. In the near future, high demands on cell technologies regarding efficiency, as shown in randomized studies, will increase more focus on the use of acellular approaches based on the internal recruitment of cells without any external manipulation of cells.

BMSCs are of interest, as those cells can produce both the cartilaginous part as well as the bony part when repairing osteochondral defects. However, it has been shown that chondrocytes and MSCs differentiate and form different subtypes of cartilage: a hyaline and a mixed cartilage phenotype, respectively.

Subsequently, to be successful in tissue engineering of cartilage injuries, one has to pay attention to both the osseous and cartilaginous parts: the use of chondrocytes for the cartilage layers and BMSCs for the bony part. At the same time, increased knowledge is needed of which type of matrix permits the cells used to differentiate the way that the different layers of cartilage can be produced, including the important calcified layer in between the chondrocyte-repaired area and subchondral bone. The aim is to tune the cells by cell recruitment, improve cell-to-cell talk, and finally with such cellular synergy produce tissue as near to regeneration as possible. Regeneration of cartilage is one thing, but the formation of functional repair tissue may be enough, and it is a clinical reality. Clinically, there are several studies showing that different types of porous osteochondral implants induce repair tissue that can give treated patients pain relief and good-quality functional recovery. Those implants are based on the ingrowth of solely bone marrow cells with or without growth factor stimulation. Those repair methods are nice to be able to offer the injured patient. However, we need to continue our research to perfect cartilage repair to finally be able to achieve regeneration.

While mammals form fibrocartilage repair tissue in response to full-thickness cartilage lesions, it seems that amphibians are able to fully restore the articular structure and cartilage matrix components without scar formation.52 The cells responsible for full regeneration in amphibians are the same type of interzonal cells as the cells responsible for joint formation in mammals.52 In the superficial zone of the cartilage layer, there are special chondrocytes with a progenitor character to be found.53,54 As mentioned earlier, those cells have different origins compared to the rest of the cartilage cells, and further focus on their function and ability to become regenerative cells is a tempting choice for the future.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments and Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Mankin HJ. The response of articular cartilage to mechanical injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(3):460-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tew S, Redman S, Kwan A, Walker E, Khan I, Dowthwaite G, et al. Differences in repair responses between immature and mature cartilage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391 Suppl):S142-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakahara H, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. Culture-expanded human periosteal-derived cells exhibit osteochondral potential in vivo. J Orthop Res. 1991;9(4):465-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gest H. The discovery of microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, fellows of the Royal Society. Notes Rec R Soc Lond. 2004;58(2):187-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wikipedia. Cell. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cell_(biology)

- 6. Sokoloff L, Bland JH. The musculoskeletal system: structure and function in disease monograph series. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Company; 1975. p. 35-42. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall BK. Bones and cartilage: developmental and evolutionary skeletal biology. San Diego: Elsevier; 2005. p. 33-45. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(14):889-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Windt TS, Concaro S, Lindahl A, Saris DB, Brittberg M. Strategies for patient profiling in articular cartilage repair of the knee: a prospective cohort of patients treated by one experienced cartilage surgeon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(11):2225-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hangody L, Vásárhelyi G, Hangody LR, Sükösd Z, Tibay G, Bartha L, Bodó G. Autologous osteochondral grafting: technique and long-term results. Injury. 2008;39 Suppl 1:S32-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brittberg M. Cell carriers as the next generation of cell therapy for cartilage repair: a review of the matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation procedure. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(6):1259-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeon JE, Vaquette C, Klein TJ, Hutmacher DW. Perspectives in multiphasic osteochondral tissue engineering. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2014;297(1):26-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shimomura K, Moriguchi Y, Murawski CD, Yoshikawa H, Nakamura N. Osteochondral tissue engineering with biphasic scaffold: current strategies and techniques. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. Epub 2014 Feb 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tallheden T, Dennis JE, Lennon DP, Sjögren-Jansson E, Caplan AI, Lindahl A. Phenotypic plasticity of human articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A Suppl 2:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karlsson C, Brantsing C, Svensson T, Brisby H, Asp J, Tallheden T, Lindahl A. Differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and articular chondrocytes: analysis of chondrogenic potential and expression pattern of differentiation-related transcription factors. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(2):152-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kreuz PC, Steinwachs MR, Erggelet C, Krause SJ, Konrad G, Uhl M, Südkamp N. Results after microfracture of full-thickness chondral defects in different compartments in the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(11):1119-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, Kreuz PC, Mandelbaum BR. Clinical efficacy of the microfracture technique for articular cartilage repair in the knee: an evidence-based systematic analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):2053-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Kumar A. Long-term results after microfracture treatment for full-thickness knee chondral lesions in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Epub 2013 Sep 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Engen C, Engebretsen L, Aroen A. Knee cartilage defect patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials are not representative of patients in orthopedic practice. Cartilage. 2010;1:312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Im GI. Is continuous treatment with transforming growth factor-beta necessary to induce chondrogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells? Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;190(1):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pelttari K, Winter A, Steck E, Goetzke K, Hennig T, Ochs BG, et al. Premature induction of hypertrophy during in vitro chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells correlates with calcification and vascular invasion after ectopic transplantation in SCID mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3254-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Farrell MJ, Fisher MB, Huang AH, Shin JI, Farrell KM, Mauck RL. Functional properties of bone marrow-derived MSC-based engineered cartilage are unstable with very long-term in vitro culture. J Biomech. Epub 2013 Oct 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vinardell T, Sheehy EJ, Buckley CT, Kelly DJ. A comparison of the functionality and in vivo phenotypic stability of cartilaginous tissues engineered from different stem cell sources. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(11-12):1161-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carroll SF, Buckley CT, Kelly DJ. Cyclic hydrostatic pressure promotes a stable cartilage phenotype and enhances the functional development of cartilaginous grafts engineered using multipotent stromal cells isolated from bone marrow and infrapatellar fat pad. J Biomech. Epub 2013 Dec 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCarthy HS, Roberts S. A histological comparison of the repair tissue formed when using either Chondrogide(®) or periosteum during autologous chondrocyte implantation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(12):2048-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brittberg M, Sjögren-Jansson E, Thornemo M, Faber B, Tarkowski A, Peterson L, Lindahl A. Clonal growth of human articular cartilage and the functional role of the periosteum in chondrogenesis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(2):146-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mochizuki T, Muneta T, Sakaguchi Y, Nimura A, Yokoyama A, Koga H, Sekiya I. Higher chondrogenic potential of fibrous synovium- and adipose synovium-derived cells compared with subcutaneous fat-derived cells: distinguishing properties of mesenchymal stem cells in humans. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):843-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koga H, Muneta T, Nagase T, Nimura A, Ju YJ, Mochizuki T, Sekiya I. Comparison of mesenchymal tissues-derived stem cells for in vivo chondrogenesis: suitable conditions for cell therapy of cartilage defects in rabbit. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;333(2):207-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimomura K, Ando W, Tateishi K, Nansai R, Fujie H, Hart DA, et al. The influence of skeletal maturity on allogenic synovial mesenchymal stem cell-based repair of cartilage in a large animal model. Biomaterials. 2010;31(31):8004-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hellingman CA, Koevoet W, van Osch GJ. Can one generate stable hyaline cartilage from adult mesenchymal stem cells? A developmental approach. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6(10):e1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hiramatsu K, Sasagawa S, Outani H, Nakagawa K, Yoshikawa H, Tsumaki N. Generation of hyaline cartilaginous tissue from mouse adult dermal fibroblast culture by defined factors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(2):640-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jukes JM, van Blitterswijk CA, de Boer J. Skeletal tissue engineering using embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4(3):165-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gutierrez-Aranda I, Ramos-Mejia V, Bueno C, Munoz-Lopez M, Real PJ, Mácia A, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells develop teratoma more efficiently and faster than human embryonic stem cells regardless the site of injection. Stem Cells. 2010;28(9):1568-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uto S, Nishizawa S, Takasawa Y, Asawa Y, Fujihara Y, Takato T, Hoshi K. Bone and cartilage repair by transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cells in murine joint defect model. Biomed Res. 2013;34(6):281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mehlhorn AT, Schmal H, Kaiser S, Lepski G, Finkenzeller G, Stark GB, Südkamp NP. Mesenchymal stem cells maintain TGF-beta-mediated chondrogenic phenotype in alginate bead culture. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(6):1393-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freed LE, Marquis JC, Nohria A, Emmanual J, Mikos AG, Langer R. Neocartilage formation in vitro and in vivo using cells cultured on synthetic biodegradable polymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27(1):11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Steinwachs M. New technique for cell-seeded collagen-matrix-supported autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(2):208-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurtis MS, Schmidt TA, Bugbee WD, Loeser RF, Sah RL. Integrin-mediated adhesion of human articular chondrocytes to cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Manolopoulos V, Marshall KW, Zhang H, Trogadis J, Tremblay L, Doherty PJ. Factors affecting the efficacy of bovine chondrocyte transplantation in vitro. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7(5):453-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H, Kandel RA. Chondrocytes attach to hyaline or calcified cartilage and bone. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(1):56-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grigolo B, Lisignoli G, Piacentini A, Fiorini M, Gobbi P, Mazzotti G, et al. Evidence for redifferentiation of human chondrocytes grown on a hyaluronan-based biomaterial (HYAff 11): molecular, immunohistochemical and ultrastr-uctural analysis. Biomaterials. 2002;23(4):1187-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ionescu LC, Mauck RL. Porosity and cell preseeding influence electrospun scaffold maturation and meniscus integration in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19(3-4):538-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hartmann C, Tabin CJ. Wnt-14 plays a pivotal role in inducing synovial joint formation in the developing appendicular skeleton. Cell. 2001;104(3):341-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Storm EE, Kingsley DM. GDF5 coordinates bone and joint formation during digit development. Dev Biol. 1999;209(1):11-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koyama E, Shibukawa Y, Nagayama M, Sugito H, Young B, Yuasa T, et al. A distinct cohort of progenitor cells participates in synovial joint and articular cartilage formation during mouse limb skeletogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;316(1):62-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pacifici M, Koyama E, Iwamoto M, Gentili C. Development of articular cartilage: what do we know about it and how may it occur? Connect Tissue Res. 2000;41(3):175-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang W, Chen J, Tao J, Hu C, Chen L, Zhao H, et al. The promotion of osteochondral repair by combined intra-articular injection of parathyroid hormone-related protein and implantation of a bi-layer collagen-silk scaffold. Biomaterials. 2013;34(25):6046-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shimomura K, Moriguchi Y, Ando W, Nansai R, Fujie H, Hart DA, et al. Osteochondral repair using a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from synovial mesenchymal stem cells and a hydroxyapatite-based artificial bone. Tissue Eng Part A. Epub 2014 Mar 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li Q, Tang J, Wang R, Bei C, Xin L, Zeng Y, Tang X. Comparing the chondrogenic potential in vivo of autogeneic mesenchymal stem cells derived from different tissues. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2011;39(1):31-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cleary MA, van Osch GJ, Brama PA, Hellingman CA, Narcisi R. FGF, TGFβ and Wnt crosstalk: embryonic to in vitro cartilage development from mesenchymal stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. Epub 2013. April 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bian L, Zhai DY, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Coculture of human mesenchymal stem cells and articular chondrocytes reduces hypertrophy and enhances functional properties of engineered cartilage. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17(7-8):1137-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cosden RS, Lattermann C, Romine S, Gao J, Voss SR, MacLeod JN. Intrinsic repair of full-thickness articular cartilage defects in the axolotl salamander. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(2):200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dowthwaite GP, Bishop JC, Redman SN, Khan IM, Rooney P, Evans DJ, et al. The surface of articular cartilage contains a progenitor cell population. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 6):889-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Williams R, Khan IM, Richardson K, Nelson L, McCarthy HE, Analbelsi T, et al. Identification and clonal characterisation of a progenitor cell sub-population in normal human articular cartilage. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]