Abstract

AIM: Although most patients with achalasia respond to pneumatic dilation, one-third experienced recurrence, and prolonged follow-up studies on parameters associated with various outcomes are scanty. In this retrospective study, we reported a 15-years’ experience with pneumatic dilation treatment in patients with primary achalasia, and determined whether previously described predictors of outcome remain significant after endoscopic dilation.

METHODS: Between September 1989 and September 2004, 39 consecutive patients with primary symptomatic achalasia (diagnosed by clinical presentation, esophagoscopy, barium esophagogram, and manometry) who received balloon dilation were followed up at regular intervals in person or by phone interview. Remission was assessed by a structured interview and a previous symptoms score. The median dysphagia-free duration was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

RESULTS: Symptoms were dysphagia (n = 39, 100%), regurgitation (n = 23, 58.7%), chest pain (n = 4, 10.2%), and weight loss (n = 26, 66.6%). A total of 74 dilations were performed in 39 patients; 13 patients (28%) underwent a single dilation, 17 patients (48.7%) required a second procedure within a median of 26.7 mo (range 5-97 mo), and 9 patients (23.3%) underwent a third procedure within a median of 47.8 mo (range 37-120 mo). Post-dilation lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, assessed in 35 patients, has decreased from a baseline of 35.8 ± 10.4-10.0 ± 7.1 mmHg after the procedure. The median follow-up period was 9.3 years (range 0.5-15 years). The dysphagia-free duration by Kaplan-Meier analysis was 78%, 61% and 58.3% after 5, 10 and 15 years respectively.

CONCLUSION: Balloon dilation is a safe and effective treatment for primary achalasia. Post-dilation LES pressure estimation may be useful in assessing response.

Keywords: Pneumatic dilation, Primary achalasia, Esophagoscopy, Barium esophagogram, Manometry

INTRODUCTION

Achalasia is a disorder of the esophagus characterized by increased lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone, lack of LES relaxation with swallowing and aperistalsis of the body of the esophagus. The etiology and pathogenesis of idiopathic achalasia are still unclear, although a viral cause, genetic influences (associations with HLA loci) and autoimmune processes have been postulated. Degeneration and significant loss of nerve fibers, associated with an inflammatory infiltration of the myenteric plexus in idiopathic achalasia, provide evidence of an immune-mediated destruction of the myenteric plexus, possibly through apoptotic process[1,2].

Current therapy is aimed at reducing the pressure gradient across the LES to allow passage of food. Therapeutic options for achalasia include pharmacologic therapy, surgical myotomy, mechanical rupture of LES smooth muscle by endoscopic balloon dilation, metal or plastic autoexpandable stent placement, and relaxation of the hypertonic muscles by injection of botulinum toxin, an inhibitor of acetylcholine release from nerve endings[3-6]. Drugs, including calcium-channel blockers, may be tried in mild cases, but their efficacy is modest and their side effects can be bothersome[3]. Besides, surgery has proved to be effective, although invasive[7]. In most cases therefore, gastroenterologists prefer pneumatic dilation as the first therapeutic step, due to its low cost[8] and high success rates, ranging from 70% to 90%. However, there is little information with regard to the patients’ long-term course following a single pneumatic dilation or after repeated therapies[3].

In 1993, we reported our experience of 31 patients with achalasia, treated with pneumatic dilation[9]. Since then, the same patient cohort was regularly reassessed at 2-year intervals and eight patients were added until September 2004, thereby obtaining a median follow-up time of 9.3 years (range 0.5-15 years).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the long-term results of endoscopic balloon dilation treatment for achalasia, over a prolonged observation period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Using records from a therapeutic endoscopy registry that has been kept in our department for a 15-year period, consecutive patients, who had undergone pneumatic dilation for achalasia from September 1989 to September 2004, were reviewed retrospectively. The diagnosis was based on clinical presentation, barium swallow contrast studies, endoscopic criteria and manometry studies. Exclusion criteria included pseudoachalasia, prior endoscopic or surgical therapy, and those with inadequate records. Patients under 14 years were also not included and they were referred to the pediatric gastrointestinal unit.

Evaluation of symptoms

Symptoms of dysphagia, retrosternal (chest) pain, regurgitation, and weight loss were evaluated at the first visit and during subsequent follow-up in the outpatient clinic of our department or by phone interview. The frequency of the symptoms was graded as following: grade 0, none; grade 1, less than once weekly; grade 2, two to three times weekly; grade 3, once daily; grade 4, more than once daily. Moreover, relative data on the effectiveness of treatment were classified as follows: (a)excellent, restoration to complete health (free of symptoms); (b)good, dysphagia or pain of short duration, defined as retrosternal hesitation of food lasting about 3 min and disappearing after drinking fluids, less than once weekly; (c) moderate, dysphagia lasting about 3 min without weight loss, more than once weekly; (d) poor, dysphagia lasting more than 3 min, accompanied by regurgitation or weight loss, more than once weekly. Clinical remission was considered as symptomatic scores of (a) and (b). Clinical recurrence in less than 3 mo following the second or subsequent dilations was considered as an indication for surgical myotomy.

Esophageal manometry

Esophageal manometry was performed in all patients after overnight fasting using a low compliance, pneumohydraulic, water infusion system (Arndofer, Medical Specialties, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and an eight lumen, manometric catheter. The catheter had four ports radially oriented (90°) near the tip and four more centrally positioned, 5 cm apart (5, 10, 15, and 20 cm from the tip). The recording sites were connected to an eight-channel polygraph (Synetics Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden). The manometric catheter assembly was passed transnasally without any sedation into the stomach. The LES pressure was determined using the station pull through technique and recorded as the mean of four measurements at mid-respiration. Completeness of LES relaxation (normal >85%) was assessed as percent decrease from resting LES pressure to gastric baseline following wet swallows. Esophageal body motility was recorded at 3, 8, 13, and 18 cm above the LES in response to 5 mL swallows of water at 30-s intervals. LES pressures and peristalsis were determined at the time of diagnosis, and 1 mo after the dilation.

The diagnostic criteria for primary achalasia were incomplete LES relaxation and aperistalsis of the esophageal body. Once the diagnosis was confirmed, the patients were asked to choose between pneumatic dilation or Heller myotomy as treatment options and gave informed consent for the procedures; they were informed that pneumatic dilation carries a 5% perforation rate with an 80% success rate, whereas Heller myotomy generally requires 1 wk of hospitalization with 3-4 wk needed for recovery and has a 90% success rate and a 10% chance of postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. All patients chose balloon distension as an initial therapeutic procedure.

Pneumatic dilation

All dilations were performed with a Rigiflex (Microvasive, Boston Scientific Corporation, Boston, MA, USA) achalasia balloon dilator by two experienced gastroenterologists. After a liquid diet for 48 h and an overnight fast, sedation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was administered using intravenous pethidine (25-50 mg), diazepam (5-10 mg) and recently midazolam (2-5 mg), as required. Following complete upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to exclude malignancy or peptic strictures, a stiff guidewire was placed into the stomach through the endoscope. The balloon dilator was passed over the guidewire under endoscopic guidance and positioned at the esophagogastric junction under fluoroscopic control and partly inflated with dilute water-soluble contrast medium. The position of the catheter was adjusted so that the waist of the partly inflated balloon caused by the LES lay at the midpoint of the balloon. Maintaining the balloon catheter into position by fixation against the bite guard, the balloon was fully inflated with dilute water-soluble contrast. Full inflation was confirmed visually by the loss of the waist at the midpoint of the balloon and inflation was maintained for 1-3 min.

Because there is currently no consensus regarding the size of balloon that should be used for the dilation, the choice was solely based on the individual endoscopist’s preference. A water-soluble contrast examination immediately after the dilation to look for perforation was ordered only if there was clinical suspicion of perforation.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean±SD, and the paired t-test was used for statistical comparisons before and after dilation. The median dysphagia-free duration following balloon dilation was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 39 patients (17 men, 22 women) who underwent pneumatic balloon dilation for achalasia during the 15-year study period were included in the analysis. Age ranged from 27 to 87 years, with a mean age of 56 ± 11 years. Symptoms at presentation were dysphagia (n = 39, 100%), regurgitation (n = 23, 58.7%), weight loss (n = 26, 66.6%), and chest pain (n = 4, 10.2%). The mean duration of symptoms prior to treatment was 32.1 ± 56.2 mo (Table 1). Three patients with retrosternal pain were diagnosed as a vigorous achalasia by esophageal manometry. Thirteen patients underwent a single dilation, and 17 and 9 patients underwent 2 and 3 procedures respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data, presenting symptoms, number of proce-dures and follow-up of the patients

| Age (yr) [median (range)] | 56 (27 - 87) |

| Gender (M/F) | 17/22 |

| Dysphagia | 39 (100%) |

| Regurgitation | 23 (58.70%) |

| Chest pain | 4 (10.2%) |

| Weight loss | 26 (66.60%) |

| Mean duration of symptoms (mo) | 32.1 ± 56.2 |

| No of procedures | 74 |

| No of patients undergoing | |

| 1 procedure | 13 |

| 2 procedures | 17 |

| 3 procedures | 9 |

| Median follow-up (yr) (range) | 9.3 (0.5 - 15) |

The choice of the balloon size was at the discretion of individual endoscopist; a 30-mm balloon-dilator was utilized in 26 of 74 procedures (35.1%), a 35-mm balloon in 39 procedures (52.8%), and a 40-mm balloon in 9 procedures (12.1%). The balloon was inflated once per procedure in 21 of 74 (28.3%) dilations and twice per procedure in 53 of 74 (72.7%). The duration of the inflation ranged from 30 s to 2 min (median 93 s) and in each procedure obliteration of the balloon “waist” was fluoroscopically noted. Upon withdrawal, traces of blood were noted on the balloon in 21 of 74 procedures (81.1%), by using 30- and 35-mm balloon dilators in 11 and 10 procedures, respectively. Four patients (5.4%) presented post-dilation esophageal perforation (Table 2), which occurred during the initial dilation with a 30-mm balloon dilator. The esophageal perforations were successfully managed with surgical intervention. In one (1.3%) patient tachycardia (120/min) and hypotension (70/40 mmHg) were developed 5 h after the procedure by using a 35 -mm balloon dilator, followed by hematemesis and a drop of the Ht from 44% to 30%. After administration of crystalloids solutions and 4 units of blood, an emergency endoscopy disclosed a mucosal tear (Mallory-Weiss) 0.7 cm in length, with an overlying clot on the anterior wall of the esophagogastric junction. Bleeding stopped spontaneously and the patient’s course was uneventful. The median hospital stay was 1.9 d (range 1-21 d); all four patients who underwent operation for post-dilation esophageal perforation required parenteral nutrition for 7-11 d and no mortality was recorded.

Table 2.

Post-dilation complications

| Perforation | 4 (5.4%) |

| Bleeding | 1 (1.3%) |

A significant improvement in symptom score and LES pressure was noted 1 mo post-treatment (Table 3). The median follow-up period was 9.3 years (range 0.5-15 years) (Table 1).

Table 3.

Symptom score and LES pressure at baseline and 1 mo after dilation

| Baseline | After 1 mo | P | |

| Dysphagia | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | < 0.01 |

| Regurgitation | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | < 0.01 |

| Chest pain | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | < 0.05 |

| Weight loss | 8.3 ± 2.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | < 0.01 |

| LES pressure | 35.8 ± 10.4 (15-63) | 10.0 ± 7.1 (0-13) | < 0.01 |

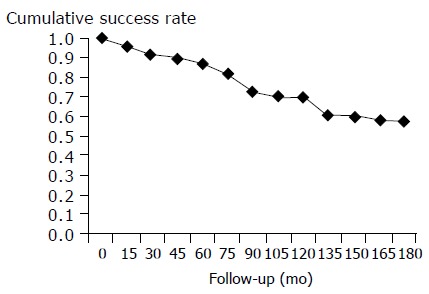

The overall cumulative success rates at 5, 10, and 15 years after balloon dilation for achalasia were 78%, 61%, and 58.3% respectively (Figure 1) . At their last attendance for follow-up, 20 of 29 patients (68%) complained for mild intermittent dysphagia, and 9 of 29 (32%) for moderate intermittent dysphagia.

Figure 1.

Cumulative success rate with pneumatic balloon dilation during the 15-yr study period.

Within the 15-year follow-up period, balloon dilation was considered to have failed in one patient, three patients died from unrelated causes and six young patients (2 men, 4 women) with a median age of 32 years (range 19-46 years) decided to undergo Heller myotomy after a median follow-up period of 34 mo (range 14-93), and could not be further contacted.

DISCUSSION

Physiologic studies have established the occurrence of denervation of the smooth muscle segment of the esophagus in patients with achalasia. A loss of ganglion cells (possibly through an apoptotic attack of T lymphocytes against nerve fibers and ganglia) in the region of the LES, particularly if the loss is predominantly of inhibitory neurons, would lead to an increased basal pressure and poor relaxation[2]. In particular, electron microscopic examination of the esophageal vagal branches reveals degeneration of myelin sheaths and disruption of axonal membranes, the valerian degenerative changes characteristic of experimental nerve transaction. Degenerative changes, including fragmentation and dissolution of nuclear material, have also been reported in ganglia of the vagal dorsal motor nucleus during the apoptotic process[10-12]. Ganglion cells degeneration in the esophageal body itself would ultimately result in permanent aperistalsis and allow for dilation of the esophagus. The damage in the LES might be the earliest event, and the aperistalsis of some early nondilated cases might be related to the obstruction of the esophagus at the level of the sphincter. After reduction in LES pressure by pneumatic dilation or myotomy in these patients, occasional peristalsis may be observed[13].

In this regard, pneumatic dilation has been the first -line therapeutic option for achalasia. The reported success rate varies widely, with figures ranging from 59% to 93% in a review by Vaezi and Richter[14]; the differences may result from variations in the definition of success used, and in the techniques applied. The Rigiflex balloon dilator has been used in our department for the last 15 years, and data from the group of patients studied in this report compare favorably with data of previous studies, with an initial success rate of more than 80% in the 1st year and a overall cumulative success rates at 5, 10, and 15 years of 78%, 61%, and 58.3% respectively. A standardized protocol for the size of the Rigiflex dilator was not used.

The most extensive experience with objective evaluations of treatment responses after pneumatic dilation relates to determination of LES pressures[15-24]. In nine of these invest-igations, improvement in symptoms correlated significantly with decrease in LES pressure, and optimal response was found in patients exhibiting a post-dilation sphincter pressure of less than 10 mmHg, or of >50% reduction from baseline. With a post-dilation LES pressure of 10 ± 7.1 mmHg achieved in our patients, the current study extends these observations by showing that post-dilation LES pressure appears to be helpful in assessing the long-term clinical response.

Apart from a significant fall in LES pressure, several authors have tried to determine other factors that predict clinical outcome following pneumatic dilation. In these studies, advanced age, a moderately dilated esophagus and a long history of symptoms prior to diagnosis were all found to predict a favorable treatment result[14,25-27], whereas male gender was found to predict a poor outcome[15]. However, the most significant factor predicting response to treatment appears to be the age at diagnosis. The results of our study with patients’ advanced age (70% of cases), confirm and strengthen this observation. Although the reason for these differences in treatment remains unknown, it has been speculated that a general difference in muscle strength across the age groups may account for this observation[28].

The perforation rate with the Rigiflex balloon dilator ranges from 0% to 6.6%[29], and graded balloon dilation starting with a 30 -mm balloon dilator and progressing to 35 and 40 mm if necessary appears to be the safest approach[30]. In the present series, 5.4% of dilations were complicated by perforation. Despite the common belief that dilation with a larger balloon (35 or 40 mm) increases the chance of perforation, all perforations observed in the present series occurred during the initial dilation with a 30-mm balloon dilator. In our study, gastrograffin swallowing was performed following dilation only when there was clinical suspicion of perforation, despite the fact that the use of immediate contrast studies to exclude perforation had become routine in the late 1970s and that this approach is recommended in several studies and textbooks. It must be emphasized that an immediate contrast study may not always exclude a perforation that may become clinically evident several hours later[30].

Less common complications including intramural hematoma, diverticula of the gastric cardia, mucosal tears, reflux esophagitis, prolonged post -procedure chest pain, fever, hematemesis with or without changes in hematocrit, and angina may occur after pneumatic dilation[30]. In our series, a patient developed hematemesis due to a Mallory-Weiss lesion, which is an uncommon complication.

Eckardt et al[16] reported that the size of the balloon dilator can predict a favorable outcome after a single dilation. In contrast, the present study suggests that the use of both 30- and 35-mm balloons exerts a similar good outcome.

Finally, there is no consensus as to whether repeated pneumatic dilations are associated with longer remission or not[31,32]. A number of studies have shown that the additional sessions of pneumatic dilations are followed by a longer duration of remission, while others believe that subsequent pneumatic dilations after the second or third dilation are less likely to result in a sustained remission, and surgical intervention should be considered for patients who have had two or three unsuccessful sessions of pneumatic dilations[15,16,24,33]. According to our clinical experience, better long -term results of pneumatic dilation can be achieved with repeated procedures, because additional procedures improve the initial success and are followed by progressively longer duration of remission.

In conclusion, this study shows that pneumatic dilation is a safe and effective treatment for achalasia, with a long duration of efficacy; once, twice and rarely thrice pneumatic dilation appears to provide good results in the majority of patients.

Footnotes

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

References

- 1.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Esophageal motor disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1999;15:339–346. doi: 10.1097/00001574-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kountouras J, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D. Apoptosis and autoimmunity as proposed pathogenetic links between Helicobacter pylori infection and idiopathic achalasia. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunaway PM, Wong RK. Achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s11938-001-0051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng YS, Li MH, Chen WX, Chen NW, Zhuang QX, Shang KZ. Selection and evaluation of three interventional procedures for achalasia based on long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2370–2373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao X, Pasricha PJ. Botulinum toxin for spastic GI disorders: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:219–235. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong RK. Pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:578–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patti MG, Fisichella PM, Perretta S, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Robinson T, Way LW. Impact of minimally invasive surgery on the treatment of esophageal achalasia: a decade of change. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:698–703; discussion 703-5. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor JB, Singer ME, Imperiale TF, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. The cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1516–1525. doi: 10.1023/a:1015811001267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eugenidis N, Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Contizas G, Kajagidou E, Triantopoulos J. Pneumatic dilatation in the management of achalasia: experience in 31 cases. Hellenic J Gastroenterol. 1993;6:343–347. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassella RR, Brown AL, Sayre GP, Ellis FH. Achalasia of the esophagus: pathologic and etiologic considerations. Ann Surg. 1964;160:474–487. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196409000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kountouras J, Kouklakis G, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D, Moschos J, Molyvas E, Zavos N. Apoptosis, inflammatory bowel disease and carcinogenesis: overview of international and Greek experiences. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:249–258. doi: 10.1155/2003/527060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kountouras J, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D. Apoptosis in hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:335–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clouse RE, Diamant NE. Esophageal motor and sensory function and motor disorders of the esophagus. In Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MD, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal & Liver Disease. 7th edn, W B Saunders Company. 2002. pp. 561–598. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21–35. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghoshal UC, Kumar S, Saraswat VA, Aggarwal R, Misra A, Choudhuri G. Long-term follow-up after pneumatic dilation for achalasia cardia: factors associated with treatment failure and recurrence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2304–2310. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732–1738. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso P, González-Conde B, Macenlle R, Pita S, Vázquez-Iglesias JL. Achalasia: the usefulness of manometry for evaluation of treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:536–541. doi: 10.1023/a:1026601322665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahi HM, Aggarwal R, Misra A, Agarwal DK, Naik SR. Relationship of manometric findings to symptomatic response after pneumatic dilation in achalasia cardia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998;17:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CH, Cameron AJ, Hsu JJ, Talley NJ, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, O'Connor MK, Colwell LJ, Zinsmeister AR. Achalasia: prospective evaluation of relationship between lower esoph-ageal sphincter pressure, esophageal transit, and esophageal diameter and symptoms in response to pneumatic dilation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponce J, Garrigues V, Pertejo V, Sala T, Berenguer J. Individual prediction of response to pneumatic dilation in patients with achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2135–2141. doi: 10.1007/BF02071392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelfand MD, Kozarek RA. An experience with polyethylene balloons for pneumatic dilation in achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:924–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Graded pneumatic dilation using Rigiflex achalasia dilators in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloway RH, Krosin G, Lange RC, Baue AE, McCallum RW. Radionuclide esophageal emptying of a solid meal to quantitate results of therapy in achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:771–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eckardt VF, Gockel I, Bernhard G. Pneumatic dilation for achalasia: late results of a prospective follow up investigation. Gut. 2004;53:629–633. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett JL, Eisenman R, Nostrant TT, Elta GH. Witzel pneumatic dilation for achalasia: safety and long-term efficacy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:482–485. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz PO, Gilbert J, Castell DO. Pneumatic dilatation is effective long-term treatment for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1973–1977. doi: 10.1023/a:1018886626144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fellows IW, Ogilvie AL, Atkinson M. Pneumatic dilatation in achalasia. Gut. 1983;24:1020–1023. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.11.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richter JE. Comparison and cost analysis of different treatment strategies in achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:359–70, viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seelig MH, DeVault KR, Seelig SK, Klingler PJ, Branton SA, Floch NR, Bammer T, Hinder RA. Treatment of achalasia: recent advances in surgery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:202–207. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Pneumatic balloon dilation for esophageal achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:325–46, vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanderson DR, Ellis FH, Olsen AM. Achalasia of the esophagus: results of therapy by dilation, 1950-1967. Chest. 1970;58:116–121. doi: 10.1378/chest.58.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkman HP, Reynolds JC, Ouyang A, Rosato EF, Eisenberg JM, Cohen S. Pneumatic dilatation or esophagomyotomy treatment for idiopathic achalasia: clinical outcomes and cost analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01296777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikaeli J, Bishehsari F, Montazeri G, Yaghoobi M, Malekzadeh R. Pneumatic balloon dilatation in achalasia: a prospective comparison of safety and efficacy with different balloon diameters. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]