Abstract

Aim:

The differentiation between neonatal hepatitis (NH) and extrahepatic biliary atresia (EHBA) is not always possible despite all the currently available diagnostic modalities. In this study, an attempt has been made to evaluate the role of nitric oxide (NO) levels in the peripheral blood to differentiate between the two conditions, one requiring early surgical intervention (EHBA) and the other amenable to conservative medical management (NH).

Patients and Methods:

Twenty patients who presented to the pediatric surgical service, over a 2 years period, with features of neonatal cholestasis were enrolled in the study. The diagnostic workup included documentation of history and clinical examination, biochemical liver function tests, ultrasonography, hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HS), and magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreaticography (MRCP). These patients did not show excretion on HS and intrahepatic ducts on MRCP. Hence, they were subjected to mini-laparotomy and operative cholangiography (OC). The EHBA patients were treated with the Kasai's portoenterostomy procedure, and the extrahepatic ducts were flushed with normal saline in NH patients. All patients were evaluated preoperatively for levels of NO in the peripheral blood by the Greiss reaction spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. Normal values were determined from a cohort of controls. The median (range) levels of NO in patients with EHBA and NH were compared, and the statistical significance of the difference was calculated by applying the Wilcox Rank Sum test. A P = 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results:

Of the 20 patients enrolled in the study, 17 patients were treated for EHBA (Group I) and the remaining 3 patients had patent ducts on OC and were thus diagnosed as NH (Group II). The mean age of the patients in Groups I and II was comparable: 2.79 ± 0.75 and 2.67 ± 0.58 months, respectively (P = 0.866). The median NO levels were significantly elevated in each of the two groups as compared to the controls (5.6 μmol/l, range 1.26-11.34 μmol/l); when compared among themselves, the NO levels were significantly higher in Group I, 64.05 μmol/l (range 24.11-89.43 μmol/l), when compared with Group II, 41.72 μmol/l (range 23.53-45.63 μmol/l) (P = 0.022).

Conclusion:

The serum levels of NO were found to be significantly higher in patients with EHBA as compared to those with NH. Hence, this may be a useful biochemical marker for the preoperative differentiation of EHBA from NH. However, a larger study is required for establishing the validity of the statistical significance.

KEY WORDS: Biliary atresia, infantile obstructive cholangiopathy, neonatal hepatitis, nitric oxide

INTRODUCTION

Extrahepatic biliary atresia (EHBA) and idiopathic neonatal hepatitis (NH) are two important causes of cholestatic jaundice in infants. Both these conditions have an overlapping spectrum of clinical presentation. Biochemical liver function tests (LFT), including gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP), and imaging studies, e.g., ultrasonography (US), magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreaticography (MRCP), and hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HS); and liver biopsy are the major diagnostic investigations that are used for the purpose of differentiating the patients who require surgery (EHBA) from the group that can be managed conservatively (NH).[1] Despite the multi-disciplinary approach to address the issue, there is a subgroup of patients in whom the differentiation is still not possible without a peroperative cholangiography (OC). The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of nitric oxide (NO) levels in the peripheral blood as a noninvasive, reliable, and reproducible test to differentiate NH from EHBA.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This prospective study was conducted with the prior approval of the institutional ethics committee. As a part of our treatment protocol, we perform a peroperative cholangiogram in all the patients with neonatal cholestasis in whom the diagnosis of EHBA is suspected and differentiation from NH is not possible with the available diagnostic modalities. These include documentation of history and clinical examination, LFT, US, HS, and MRCP. This pilot study included 20 consecutive patients who were treated in our institute by a single surgeon (VB) during a 2 years period after obtaining informed consent from the parents or guardians. Since the imaging investigations were inconclusive, the final diagnosis was made on the basis of a mini-laparotomy via a 2.0 cm right subcostal incision. An OC was performed in the patients who had a patent (nonatretic) gallbladder; those with an atretic gallbladder were diagnosed as EHBA. The patients in whom proximal and distal ducts were not patent on OC were also diagnosed as EHBA (Group I); all EHBA patients were treated with Kasai's portoenterostomy (n = 17). Those, in whom the ducts were patent, were diagnosed as NH (Group II) and in these patients the gallbladder and ducts were flushed with 10 ml of normal saline (n = 3). Long-term postoperative management included antibiotic prophylaxis (cephalosporin 30 mg/kg/OD × 1 m), cholagogues (ursodeoxycholic acid 15 mg/kg/OD and phenobarbitone 3 mg/kg/OD × 3 m), and steroids (betnesol 2 drops BD × 3 months).

Control group

We have imported the data pertaining to the peripheral blood NO in normal population from another study by the same authors.[2] The total number of controls used for statistical analysis is 25.

Bio-chemical analysis

Preoperative levels of NO were determined in all patients; blood samples were drawn from a visible peripheral vein and collected in heparinized vacutainer tubes and immediately transported to the laboratory in a cooler with ice. Upon arrival in the laboratory, the plasma was separated by centrifugation (+40°C, 3000 rpm, 10 min) and stored in 0.5-1.0 ml aliquots, placed in cryovials and stored at −70°C until analyzed.

The plasma concentration of NO was measured as its stable metabolites nitrate and nitrite. Nitrate was first reduced to nitrite by nitrate reductase, and then the plasma level of nitrite was evaluated spectrophotometrically by the Greiss reaction. The Greiss reagent, used in this procedure, is a 1:1 mixture of 0.2% N-(1 naphthyl)-ethylene-diamine and sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid. It gives a red-violet Diazo dye with nitrite, and can be detected in the visible range at 540 nm.[2]

Statistical analysis

The median (range) values of peripheral blood NO in Groups I and II were compared. The statistical analysis was done using STATA 9.0 (College Station, Texas, USA). The data were described as median (range) rather than mean owing to the small numbers. The significance of the difference between the medians of Groups I and II was assessed using the Wilcox Rank Sum test. A P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULTS

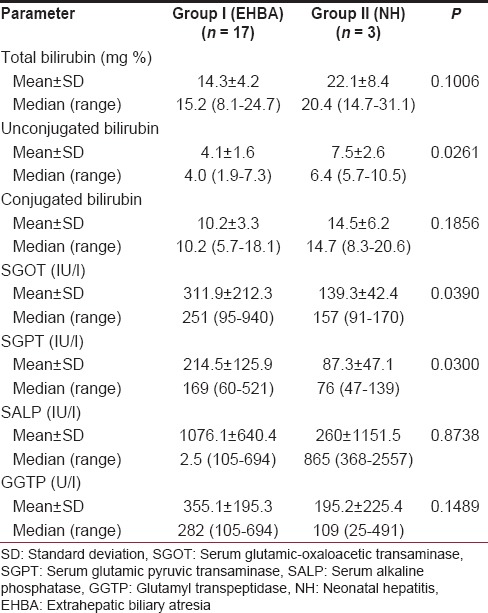

The mean age of the patients in the two groups was comparable; 2.79 ± 0.75 months for Group I and 2.67 ± 0.58 months for Group II (P = 0.866). The various parameters pertaining to the LFT have been compared between the two groups of patients in Table 1.

Table 1.

Various parameters pertaining to the liver function tests in patients with biliary atresia as compared to the patients with neonatal hepatitis

The median NO level for the control population was 5.6 μmol/l, range 1.26-11.34 μmol/l (mean 5.46 ± 1.88 μmol/l). The NO level for the patients of Groups I and II taken together as a group was median 58.80 μmol/l, range 23.53-89.43 μmol/l (mean 58.61 ± 18.06). A comparison between combined Groups I and II revealed that the NO levels were significantly higher in the patients of EHBA and NH as compared to the controls (P = 0.0000).

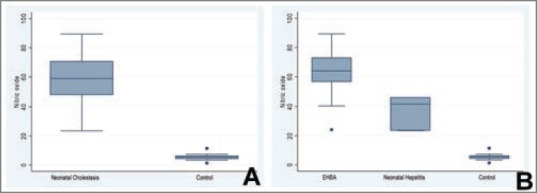

The NO levels for Group I were median 64.05 μmol/l, range 24.11-89.43 μmol/l (mean 62.43 ± 16.33 μmol/l), and for Group II were median 41.72 μmol/l, range 23.53-45.63 μmol/l (mean 36.96 ± 11.79 μmol/l). Thus, NO levels were significantly higher in EHBA patients as compared to the control population (P = 0.0000). Similarly, NO levels were significantly higher in NH patients as compared to the control population (P = 0.0053) [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) Graphical representation of the levels of nitric oxide (NO) (μmol/l) in patients with neonatal cholestasis (Groups I and II taken together) as compared to the control group. (b) Graphical representation of the levels of NO (μmol/l) in patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia (Group I), neonatal hepatitis (Group II) and in the control group

Nitric oxide levels were significantly higher in Group I (EHBA) patients as compared to Group II (NH) patients (P = 0.022) [Figure 1b].

DISCUSSION

Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is mostly physiological and self-limited. This is characterized by elevation of the unconjugated fraction of bilirubin. Cholestasis, on the other hand, is characterized by elevation of the conjugated or direct bilirubin fraction. Unlike unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, which can be physiologic, cholestasis is always pathologic, and prompt differentiation is mandatory. Idiopathic NH and EHBA are two important causes of neonatal cholestasis.[3,4]

The differentiation of idiopathic NH from EHBA becomes important from the management point of view. Typically, the infants in the EHBA group are term babies with normal birth weight and they present with clinically evident jaundice, high-colored urine, and acholic stools. The absence of stool pigment consistently favors the diagnosis of EHBA. A firm, enlarged liver is another typical finding. On the other hand, infants with NH are more likely to have been the product of an abnormal pregnancy with frequent prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, and other abnormalities. Clinically, 50% of these infants have jaundice in the 1st week of life. Hepatosplenomegaly is a common finding, and approximately one-third of these infants fail to thrive. Acholic stools may be present in these patients but are less common and intermittent.

Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreaticography has been reported to have sensitivity and a specificity of 85.29% and 57.14%, respectively, for the diagnosis of EHBA. About 71.01% accuracy of MRCP for differentiation between BA and NH was reported recently by Yang et al.[5] Sonography is more helpful in making the diagnosis of choledochal cysts. However, it can also suggest the possibility of EHBA based on the finding of an absent gallbladder and a triangular cord sign.[6,7,8] The sensitivity and specificity of a small or absent gallbladder in detecting obstruction range from 73% to 100% and from 67% to 100%, respectively, when correlated with pathologic, surgical, and subsequent clinical examinations.[3] The sensitivity and specificity of scintigraphy in detecting obstruction range from 83% to 100% and from 33% to 100%, respectively.[3] Percutaneous liver biopsy has also been employed in the differentiation of biliary atresia from NH with a reported accuracy of 96.9%.[4,9,10,11]

However, with the currently available diagnostic modalities, it is still not always possible to make the differentiation between the two because of considerable overlap in clinical features and investigative findings. There are patients with NH who need to be subjected to an OC to rule out the possibility of EHBA. It is this subgroup of patients who need a better diagnostic modality to avoid the trauma of a surgical procedure.

A variable degree of hepatic fibrosis is invariably present in almost all patients with EHBA even at the time of first presentation. This is especially true when the presentation is relatively late. As a result, these patients invariably have some degree of portal hypertension.

Portal hypertension is characterized by decreased hepatic bioavailability of NO and a relative excess in regional NO generation in the splanchnic (and systemic) circulation.[12,13] The elevated level of NO plays a critical role in the development and maintenance of the hyperdynamic circulation in acute portal hypertension and is a key factor in the maintenance of the hyperdynamic circulation in chronic portal hypertension.[14] The decreased production of NO in the hepatic microcirculation may be important in the development of parenchymal tissue damage in portal hypertension.

Based on available information, we have reported a significant elevation of NO in the peripheral circulation of children with portal hypertension caused by extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. These levels decrease after the creation of a portosystemic shunt and increase again in the event of a blocked shunt.[14] On the basis of this study, we hypothesized that patients of EHBA, who are known to have significant portal hypertension as a result of portal fibrosis and/or secondary biliary cirrhosis, should have significantly elevated levels of NO in the blood. In comparison, the patients of idiopathic NH who do not have portal fibrosis/secondary biliary cirrhosis but have inflammatory changes should have lesser degrees of portal hypertension if at all and hence, the elevation of NO should be less. This prospective study was designed to validate this hypothesis.

In this study, we have tried to differentiate between EHBA and NH on the basis of various parameters, which collectively constitute the LFTs. The two groups differed from each other with regards to the levels of unconjugated bilirubin, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase. The levels of GGTP are found to be higher in the patients with EHBA as compared to the patients with NH, however, the difference is not statistically significant. The levels of NO in the peripheral venous blood are elevated in both these groups of patients; the levels are relatively higher in patients of EHBA as compared to those of idiopathic NH and the difference between the two has been found to be statistically significant.

CONCLUSIONS

Nitric oxide may prove to be an important marker in differentiating the two conditions. Although this study is based on a small number of patients, it subtly hints toward the usefulness of NO in this direction and is an indication for further research in this direction incorporating histopathological evaluation and portal pressure measurements. The blood levels of NO in association with other biochemical parameters and imaging studies may provide us with an algorithm for the noninvasive preoperative differentiation of EHBA from NH.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta DK, Srinivas M, Bajpai M. AIIMS clinical score: A reliable aid to distinguish neonatal hepatitis from extra hepatic biliary atresia. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:605–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02752271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goel P, Srivastava K, Das N, Bhatnagar V. The role of nitric oxide in portal hypertension caused by extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2010;15:117–21. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.72433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer V, Freese DK, Whitington PF, Olson AD, Brewer F, Colletti RB, et al. Guideline for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in infants: Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:115–28. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200408000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowat AP, Psacharopoulos HT, Williams R. Extrahepatic biliary atresia versus neonatal hepatitis. Review of 137 prospectively investigated infants. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:763–70. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.10.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JG, Ma DQ, Peng Y, Song L, Li CL. Comparison of different diagnostic methods for differentiating biliary atresia from idiopathic neonatal hepatitis. Clin Imaging. 2009;33:439–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanegawa K, Akasaka Y, Kitamura E, Nishiyama S, Muraji T, Nishijima E, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of biliary atresia in pediatric patients using the “triangular cord” sign versus gallbladder length and contraction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1387–90. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.5.1811387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan Kendrick AP, Phua KB, Ooi BC, Subramaniam R, Tan CE, Goh AS. Making the diagnosis of biliary atresia using the triangular cord sign and gallbladder length. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s002470050017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrant P, Meire HB, Mieli-Vergani G. Ultrasound features of the gall bladder in infants presenting with conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:1154–8. doi: 10.1259/bjr.73.875.11144791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohnuma N, Takahashi T, Tanabe M, Yoshida H, Iwai J. The role of ERCP in biliary atresia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:365–70. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el-Youssef M, Whitington PF. Diagnostic approach to the child with hepatobiliary disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1998;18:195–202. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wongsawasdi L, Ukarapol N, Visrutaratna P, Singhavejsakul J, Kattipattanapong V. Diagnostic evaluation of infantile cholestasis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:345–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudenhoefer AA, Loureiro-Silva MR, Cadelina GW, Gupta T, Groszmann RJ. Bioactivation of nitroglycerin and vasomotor response to nitric oxide are impaired in cirrhotic rat livers. Hepatology. 2002;36:381–5. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiest R, Groszmann RJ. The paradox of nitric oxide in cirrhosis and portal hypertension: Too much, not enough. Hepatology. 2002;35:478–91. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González-Abraldes J, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J. Nitric oxide and portal hypertension. Metab Brain Dis. 2002;17:311–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1021957818240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]