Abstract

Introduction:

Cigarette smoking alters a variety of endocrine systems including thyroid hormones. Altered thyroid hormone signaling may lead to a subclinical or overt hypothyroid condition that could contribute to nicotine withdrawal-related symptoms, such as cognitive deficits. Thus, normalizing thyroid hormone levels may represent a novel therapeutic target for ameliorating nicotine withdrawal-associated cognitive deficits.

Methods:

The current studies conducted an analysis of serum thyroid hormone levels after chronic and withdrawal from chronic nicotine treatment in C57BL/6J mice using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The present studies also evaluated the effect of synthetic thyroid hormone (levothyroxine) on contextual and cued memory.

Results:

The current studies found that nicotine withdrawal reduces secreted thyroid hormone levels by 9% in C57BL/6J mice. Further, supplemental thyroid hormone not only enhanced memory in naïve animals, but also ameliorated deficits in hippocampus-dependent learning associated with nicotine withdrawal.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that smokers attempting to quit should be monitored closely for changes in thyroid function. If successfully treated, normalization of thyroid hormone levels may ameliorate some deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal and this may lead to higher rates of successful abstinence.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking alters a variety of endocrine systems including thyroid, insulin, and sex hormones (for review see Kapoor and Jones1; Tweed, Hsia, Lutfy, and Friedman2). Both active (first-hand) cigarette smoking and passive (second-hand) exposure to cigarette smoke have been shown to significantly lower steroid3,4 and thyroid hormones.5 Chronic heavy smoking (i.e., 30 or more cigarettes per day) significantly decreases thyroxine (T4), the secreted form of thyroid hormone.6 Further, chronic heavy smoking increases the prevalence of thyroid hormone deficiencies such as hypothyroxinemia (T4 levels in the lowest 5th percentile) in women of reproductive age.7 Further, chronic smoking may increase the risk of developing hypothyroidism in subjects predisposed to thyroid dysfunction (i.e., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) and smoking cessation does not abolish this risk.8 Additionally, there is recent evidence that smoking cessation confers a dramatic increase in the risk of developing autoimmune hypothyroidism.9

Adequate levels of thyroid hormones are critical for adult neural function. For example, adult-onset hypothyroidism is associated with deficits in cognitive processes including general intelligence, attention, concentration, memory, perception, visuospatial function, language, and executive functions.10–15 If smoking cigarettes negatively affects thyroid function in some individuals (i.e., those with a predisposition to thyroid dysfunction), this may contribute to negative effects on cognitive function associated with smoking and withdrawal.

The effect of cigarette smoking on thyroid function is not entirely straightforward. In contrast to the effects reported in the above paragraph, many lines of research have found that smokers have higher circulating thyroid hormone levels, which indicates that smoking may stimulate thyroid hormone secretion.16–19 Further, some studies indicate that both current and former smokers show alterations in thyroid hormones and thyroid’s regulatory hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH).20–22 Also, in stark contrast to the study by Soldin and colleagues5 described earlier, passive-smoke exposure has also been shown to increase triiodothyronine (T3), the active form of thyroid hormone and free T4.23,24 Similar to hypothyroidism-induced deficits in cognition described above, hyperthyroidism that develops in adulthood also leads to impairments in memory, attention, and executive functioning.25–28 Therefore, thyroid function likely needs to be narrowly titrated, with cognitive disturbances arising when too little or too much hormone is present. Further, thyroid disorders can result in psychological disorder diagnoses, including major depressive disorder and dementia (for review see Davis and Tremont29). Due to disparate findings in current and former smokers as well as those exposed to second-hand cigarette smoke, it is critical to understand the direction and extent of the effects of nicotine on the endocrine function of individuals.

Nicotine is the main addictive component of cigarette smoke (for review see De Biasi and Dani30; Le Foll and Goldberg31) but it is unknown if nicotine contributes to the effects of smoking on thyroid function. Cigarette smoke contains many toxic compounds that may differentially affect endocrine function,32 and the overall effects of smoking are likely complex and not necessarily unidirectional. Other components of cigarette smoke, such as thiocyanate and 2,3-hydroxypyridine, may disrupt thyroid function.1 Thiocyanate decreases iodide absorption and causes goiter in the absence of sufficient iodine.33 Decreased iodide absorption directly reduces the capacity of the thyroid to synthesize T4, which may contribute to the development of a hypothyroid state. Additionally, 2,3-hydroxypyridine prevents de-iodization (activation) of T4, indicating that there may be a reduced supply of T3, the active thyroid hormone, which could also have anti-thyroid effects. It is important to experimentally test which effects of cigarette smoking may be due to nicotine, the direction of any effects, and if nicotine withdrawal has any effect on thyroid hormone levels.

Nicotine is known to alter cognitive processes,34–36 but the effects of nicotine differ depending on treatment duration (i.e., acute, chronic, or withdrawal from chronic administration). Specifically, acute nicotine is able to enhance certain forms of learning, memory, and cognitive processes.37–41 Further, chronic nicotine can produce certain cognitive deficits42 but often tolerance to the effects of nicotine on learning is seen with chronic nicotine.43,44 More prevalent, however, are cognitive deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal40,43,44 and it is these cognitive deficits that likely drive many cases of relapse in smokers attempting to quit.45,46 The cognitive symptoms of withdrawal can be reversed by nicotine treatment in animal models.43 In addition, animal and human studies suggest that amelioration of these cognitive deficits may contribute to the efficacy of smoking cessation pharmacotherapies, such as varenicline, bupropion, and atomoxetine.47–51,76 If nicotine withdrawal affects thyroid hormone levels, then normalization of this hormone may represent a novel therapeutic strategy to boost the efficacy of smoking cessation treatments.

The current studies aimed to determine if there is a direct effect of nicotine on thyroid hormone levels. The present studies also examined the effect of supplemental thyroid hormone on hippocampus-dependent and hippocampus-independent learning and memory and on learning deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal. Thus, this study examined if a pharmacological strategy aimed at normalizing thyroid hormone levels may be efficacious in treating the cognitive deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal. It is possible that certain individuals who smoke and are predisposed to thyroid dysfunction could benefit from carefully monitored thyroid hormone status prior to and during smoking cessation attempts to alleviate cognitive dysfunction and reduce relapse rates.

Methods

Subjects

C57BL/6 mice were used for all biochemical and behavioral studies. Mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and arrived at seven weeks of age. Mice were shipped to Temple University and were acclimated to the facilities for >1 week prior to the initiation of acute or chronic nicotine treatment and/or behavioral training. All mice were maintained in a temperature and humidity controlled vivarium with ad libitum access to standard lab chow and water. All procedures were approved by the Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug Preparation and Administration

Chronic nicotine (0 or 24mg/kg/day, subcutaneous [SC]) administration occurred via osmotic minipump (model #1002 Alzet, Inc.) that delivered 0.25 µl/hr and held a total of 100 µl of liquid. One group of mice was implanted with osmotic minipumps for 13 days and was biochemically assessed for chronic nicotine exposure-induced alterations in thyroid hormone levels. Three separate cohorts of mice were implanted with osmotic minipumps for 12 days; pumps were then removed to produce spontaneous withdrawal 24hr later that could be biochemically and behaviorally assessed for changes in hormone levels and learning in a fear conditioning paradigm. Doses tested were based on previous research52–54 and subsequent dose response analyses. Levothyroxine (L-Thyroxine, L-T4, Sigma) (0, 0.3125, 0.625, and 1.25mg/kg, IP) was dissolved in 10% hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) and NaOH then normalized to a physiological pH of ~7.0. Levothyroxine was administered with an 80min pretreatment time, once a day for four days, ending on testing day for dose response curve analysis and evaluation of the efficacy of levothyroxine to ameliorate nicotine withdrawal-induced changes in hormone levels and fear conditioning based on previous research.55,56 All doses tested in behavioral tasks were lower than what was shown to be efficacious in other cognitively impaired rodent models.55,56 Our initial biochemical proof-of-principal study confirming that systemic levothyroxine administration alters serum T3 and T4 levels showed that 5mg/kg was likely far too high and doses were adjusted downward for subsequent behavioral and biochemical analyses. This may be due to differential pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of levothyroxine based on vehicle differences. Specifically, the present studies used HPβCD as a vehicle, which has been shown to increase levothyroxine bioavailability over other formulations.57 Synthetic thyroid hormone is identical to endogenous hormone58 and the lower doses used in the present studies limit the concern of off-target side-effects of levothyroxine treatment.

Osmotic Minipump Surgeries

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 2.5% maintenance) and placed on a stereotaxic instrument for pump implantation and removal surgeries. Nicotine (0 or 24mg/kg/day) filled osmotic minipumps pumps were inserted or removed from under the skin through a small instrascapular incision using sterile surgical techniques. Mice were observed to identify any adverse reactions to surgeries (none were observed).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Analyses

To evaluate the effect of chronic nicotine on thyroid hormone levels, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses were conducted on serum from mice treated with chronic nicotine (0 or 24mg/kg/day, SC) for 13 days. Next, to evaluate the effect of nicotine withdrawal, ELISA analyses were conducted on serum from mice exposed to chronic nicotine (0 or 24mg/kg/day, SC) for 12 days followed by 24hr of spontaneous withdrawal (induced by removing the osmotic minipump). Twenty-four hour time point was chosen based on previous results documenting that this is the first time point when nicotine withdrawal has been shown to disrupt hippocampus-dependent learning59 and corresponds to human nicotine withdrawal-induced cognitive symptom onset.60 Further, a group of mice (n = 4) treated for four days with 5mg/kg of L-T4 were included as a positive control and proof of concept that supplemental thyroid hormone increases circulating hormone levels. Finally, a group of mice (n = 6–7/group) treated for four days with 0.625mg/kg of L-T4 or vehicle were included to determine if supplemental thyroid hormone ameliorates nicotine withdrawal-induced reduction in circulating hormone levels. Blood (~500 μl) was collected immediately after sacrificing the mice. ELISA (Alpha Diagnostics) kits were used to evaluate total levels of thyroxine (T4, Kit #1100) and triiodothyronine (T3, Kit #1700). Briefly, approximately 500 µl blood was collected from the descending vena cava into microtainer serum collection tubes (BD) with clot activator and gel separator and tubes were immediately inverted five times to activate clotting. Blood was allowed to clot for at least 30min before being centrifuged for 5min at 10,000rpm. Resulting supernatant was collected and stored at -80 °C until analysis. ELISAs were run using manufacturer’s recommended protocols. Briefly, 25 or 50 µl (for T4 and T3 assays, respectively) serum were added to 96 well plates previously coated with anti-thyroid hormone antibodies. Due to a change in manufacturer recommendations, the ELISA kit used to determine the effect of levothyroxine on T4 levels during nicotine withdrawal used 50 µl of serum. Then, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated thyroid hormone solution was added to the wells to competitively bind to their respective antibodies for 60min at room temperature. Wells were then aspirated and washed three times prior to the addition of an HRP substrate solution. Plates were then incubated with HRP substrate solution for 15min at room temperature and a blue color developed. Finally, 50 µl stop solution was added and the blue color turned to yellow. Plates were then read on a 96 well plate reader (Bio-Rad) at 450nM. Absorbance values were inversely proportional to thyroid hormone levels. Using a standard curve, thyroid hormone levels were calculated (interpolated) and graphed. The detection limit was 0.5 μg/dl for T4 and 0.16ng/ml for T3. Also, as a more sensitive measure of thyroid hormone status,61 a T3/T4 ratio was calculated for each animal.

Contextual and Cued Fear Conditioning

Apparatus

Fear conditioning training and contextual fear conditioning testing occurred in conditioning chambers made of Plexiglas (26.5×20.4×20.8cm) with stainless steel rod grid floors (2mm diameter) spaced 1.0cm apart described previously.62 Scrambled foot-shock (0.57 mA) was administered via a shock generator (Med-Associates) controlled by LabView software. Fear conditioning chambers were housed in individual sound attenuating cubicles (Med-Associates). Each sound attenuating cubicle contained a light (4 watt) and fan that provided air circulation and a constant white noise (65 dB). Cued fear conditioning testing occurred in altered context conditioning chambers located in a different testing room. Altered context, in addition to occurring in a different testing room, also consisted of different size chambers (20×23×19cm) that differed in construction (i.e., aluminum sides and a plastic floor). Vanilla extract was added to make the context as distinct as possible. All chambers were cleaned with 70% ethanol before and after each animal.

Behavioral Assessment

Male C57BL/6J mice were trained and tested in a fear conditioning paradigm that assessed hippocampus-dependent (contextual fear conditioning) and hippocampus-independent (cued fear conditioning) learning and memory.63,64 Mice were introduced to fear conditioning chambers for 2min prior to the introduction of a 30 s conditioned stimulus (CS, white noise, 85 dB) that co-terminated with a 2 s unconditioned stimulus (US, footshock). After the initial CS-US pairing, an inter-trial-interval (2min) preceded a second CS-US pairing. The session ended after a 30 s period without stimuli and mice were returned to their homecages. Twenty-four hours later, mice were placed in the fear conditioning chambers for 5min, during which time they were assessed for freezing behavior. One hour after contextual fear conditioning testing, mice were assessed for freezing in the altered context for 6min. Mice were tested for 3min in the altered context in the absence of stimulus presentations (pre-CS), which was used as a measure of generalized freezing.65 Immediately after the pre-CS testing, the mice were assessed for freezing during a 3min presentation of the CS.

Statistical Analyses

For ELISA analyses, t-tests on calculated hormone levels were used to compare saline to nicotine treatment (chronic or withdrawal) for serum T3 levels, serum T4 levels, and serum T3/T4 ratios. An additional t-test was used to determine if levothyroxine ameliorated the nicotine withdrawal-induced changes in T4 levels. For fear conditioning studies that evaluated the effect of levothyroxine on contextual and cued fear conditioning, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was run with Dunnett’s post-hoc tests to compare treatment groups to vehicle control. For fear conditioning studies that evaluated the effect of levothyroxine on nicotine-withdrawal deficits, a one-way ANOVA was run with Dunnett’s post-hoc tests to compare all levothyroxine treatment groups to nicotine-withdrawal.

Results

Effect of Chronic and Withdrawal From Chronic Nicotine on Serum Thyroid Hormone Levels

Chronic nicotine caused no significant change in serum levels of either T3 or T4: t(16) = 0.5196, p = .6105 and t(16) = 0.7958, p = .4378, respectively (Table 1). Withdrawal from chronic nicotine produced no significant change in serum levels of T3: t(16) = 0.5831, p = .5679, but it significantly decreased serum T4 levels: t(16) = 2.237, p < .05 (Table 1). Interestingly, chronic nicotine did produce a significant increase in the serum T3/T4 ratio: t(16) = 2.612, p < .05 (Table 1), as did withdrawal from chronic nicotine: t(16) = 2.985, p < .05 (Table 1), which may indicate subtle alterations in thyroid hormone homeostasis.

Table 1.

The Effect of Chronic and Withdrawal From Chronic Nicotine Administration on Serum Thyroid Hormone Levels. Chronic Nicotine had no Effect on Either Secreted (T4) or Active (T3) Thyroid Hormone but did Increase the T3/T4 ratio. Withdrawal From Chronic Nicotine Significantly Decreased T4 Levels Without Affecting T3 Levels and Also Increased the T3/T4 Ratio. Positive Control of L-T4 Treatment is Also Included to Show Proof of Principle That L-T4 Increases Serum Thyroid Hormone Levels

| Treatment group | T3 (ng/ml) | T4 (ug/dl) | T3/T4 ratio | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic saline | 2.185±0.1420, N = 8 | 4.127±0.2608, N = 8 | 0.5303±0.01508, N = 8 | |

| Chronic nicotine (24mg/kg/day) | 2.273±0.1005, N = 10 | 3.840±0.2465, N = 10 | 0.6013±0.02105*, N = 10 | |

| Withdrawal saline | 2.244±0.07291, N = 8 | 3.910±0.09072, N = 8 | 0.5493±0.01487, N = 8 | |

| Withdrawal nicotine (24mg/kg/day) | 2.330±0.1166, N = 10 | 3.557±0.1206*, N = 10 | 0.6154±0.01581*, N = 10 | |

| Acute levothyroxine (5mg/kg) | >10, N = 4 | >25, N = 4 | n/a | |

| Acute saline + withdrawal nicotine (24mg/kg/day) | n/a | 17.9±3.0, N = 7 | n/a | Manufacturer’s ELISA protocol changed requiring higher serum volume |

| Acute levothyroxine (0.625mg/kg) + withdrawal nicotine (24mg/kg/day) | n/a | 35.5±0.29, N = 6 | n/a | Manufacturer’s ELISA protocol changed requiring higher serum volume |

ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

*p < .05.

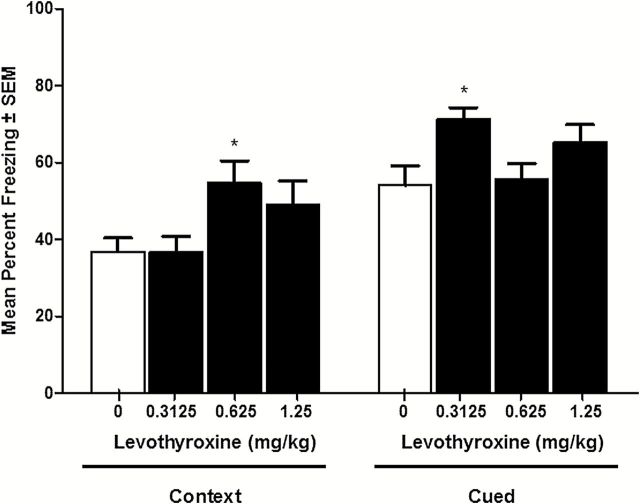

Effect of Thyroid Hormone on Contextual Fear Conditioning

To evaluate the effect of supplemental thyroid hormone, four days of levothyroxine (0, 0.3125, 0.625, and 1.25, daily [QD], intraperitoneal [IP]) was administered starting two days prior to contextual and cued fear conditioning and continuing through testing day. All drug doses occurred 80min prior to training or testing (and the same time of day on two days prior to behavioral training/testing). One-way ANOVA analysis evaluating the effect levothyroxine on contextual fear conditioning revealed a significant effect of drug treatment: F(3,47) = 3.418, p < .05 (Figure 1). Dunnett’s post-hoc tests comparing all drug treatment groups to vehicle control revealed a significant effect of levothyroxine at 0.625mg/kg, but not at lower or higher doses (p < .05). Therefore, the present results identified a subthreshold dose of levothyroxine, an effective dose of levothyroxine, and a dose of levothyroxine that likely overstimulates the thyroid hormone signaling system and does not produce significant cognitive enhancement. One-way ANOVA comparing the effect of levothyroxine on cued fear conditioning revealed a significant effect of levothyroxine: F(3,47) = 3.403, p < .05 (Figure 1). Dunnett’s post-hoc tests revealed a significant effect of levothyroxine at 0.3125mg/kg (p < .05), but not at either of the higher doses. This finding shows that a dose found to be subthreshold for enhancement of contextual fear conditioning may subtly enhance cued fear conditioning, but the dose that enhances contextual fear conditioning has no effect on cued fear conditioning.

Figure 1.

The effect of levothyroxine on contextual and cued fear conditioning. Levothyroxine significantly enhances contextual fear conditioning at a selective dose of 0.625mg/kg. Levothyroxine significantly enhances cued fear conditioning at a selective dose of 0.3125mg/kg. * indicates p < .05.

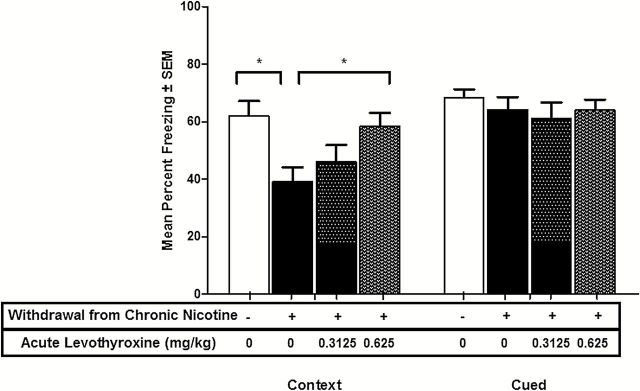

Efficacy of Levothyroxine to Ameliorate Nicotine Withdrawal-Induced Deficits in Contextual Fear Conditioning

To assess the efficacy of supplemental thyroid hormone on cognitive deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal, the present studies tested two doses of levothyroxine. The low dose of levothyroxine tested was subthreshold for affecting contextual fear conditioning alone and the higher dose of levothyroxine tested was efficacious in enhancing contextual fear conditioning alone. Cued fear conditioning was also assessed for all studies to determine if there were other cognitive effects of levothyroxine treatment during nicotine withdrawal. One-way ANOVA comparing the effects of levothyroxine on nicotine withdrawal in contextual fear conditioning revealed a significant effect: F(3,59) = 4.327, p < .05 (Figure 2). Dunnett’s post-hoc tests revealed nicotine withdrawal produced a significant disruption of hippocampus-dependent learning (p < .05), that levothyroxine (0.625mg/kg) significantly ameliorated nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits (p < .05). Further, there was no effect of subthreshold levothyroxine treatment on nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits in hippocampus-dependent learning (0.3125mg/kg). ANOVA and post-hoc tests revealed no effect of nicotine withdrawal or levothyroxine on cued fear conditioning during nicotine withdrawal: F(3,59) = 0.4022, p = .7520 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of levothyroxine on nicotine withdrawal-associated deficits in contextual fear conditioning. Levothyroxine significantly enhances contextual fear conditioning in mice experiencing nicotine withdrawal, indicating complete amelioration/reversal of nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits. Levothyroxine does not affect cued fear conditioning in mice experiencing nicotine withdrawal. * indicates p < .05.

Effect of Supplemental Levothyroxine on Withdrawal From Chronic Nicotine-Induced Alterations in T4 Levels

To determine if the behaviorally active dose of levothyroxine increased T4 levels in mice experiencing nicotine withdrawal, levothyroxine (0.625mg/kg, IP) or HPβCD was administered (as in behavioral experiments) to mice experiencing nicotine withdrawal. Levothyroxine administration significantly increased serum T4 levels in mice experiencing nicotine withdrawal (means of 17.9±3.0 µg/dl for nicotine withdrawal and 35.5±0.29 µg/dl for levothyroxine treatment during nicotine withdrawal): t(11) = 5.384, p < .05 (Table 1).

Discussion

Nicotine withdrawal leads to cognitive deficits in animals and humans.40,43,45,46,66 It is possible that decreased thyroid hormone availability may account for some of these cognitive deficits, but this had not previously been tested. The results described here show for the first time that withdrawal from chronic nicotine administration can directly reduce thyroid hormone function by decreasing levels of the secreted thyroid hormone, T4. Recent studies have revealed a profound effect of smoking cessation on the development of autoimmune hypothyroidism9 and the present results suggest that withdrawal from chronic nicotine administration may directly contribute to these observed effects. Remarkably, the current results also demonstrate that supplemental thyroid hormone treatment (i.e., levothyroxine administration) was able to completely ameliorate/reverse the hippocampus-dependent cognitive deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal. This supports a potential role of deficient thyroid hormone signaling in nicotine withdrawal-induced cognitive deficits and suggests that normalization of hormone levels may benefit subjects attempting to quit smoking.

T4 levels have been found to positively correlate with cognitive function, while T3 does not.14,67 It has been suggested that central nervous system (CNS) thyroid hormones are derived from peripheral T4, and that serum T4 levels may be important for CNS function.14 Experimental manipulations that reduce T4 levels are detrimental to learning and memory.68,69 Further, hypothyroxinemia (low T4 with normal T3 levels) during development leads to long lasting changes in cognition during adulthood.70

Additional analysis of thyroid hormone levels and the relationship between active and secreted thyroid hormone (i.e., T3/T4 ratio) revealed that both chronic and withdrawal from chronic nicotine administration significantly increased the T3/T4 ratio, which is indicative of a variety of thyroid disease states including (untreated) hypo- and hyperthyroidism.61 Even subtle deficiencies in thyroid hormone signaling, such as those observed in subclinical hypothyroidism (defined as normal T3 and T4 and elevated TSH levels), are associated with poor memory performance71–74 and benefit from thyroid hormone supplementation.72,74,75 Therefore, it may be prudent to more closely monitor thyroid hormone status in both current and former smokers to accurately detect potentially subtle changes in thyroid function.

Conclusions

The current results suggest that nicotine withdrawal significantly reduces serum thyroxine levels, and these changes may be responsible for some the cognitive deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal. Thyroid disorders are common, and their treatment is relatively straightforward. The present results demonstrate that supplemental thyroid hormone (i.e., levothyroxine) can not only enhance hippocampus-dependent and hippocampus-independent learning and memory, but they also demonstrate efficacy in ameliorating the cognitive deficits associated with nicotine withdrawal. Our behavioral data suggest that supplemental thyroid hormone may normalize thyroid hormone levels during initial abstinence from nicotine, and our biochemical analysis confirmed that levothyroxine, at behaviorally active doses, significantly increases T4 levels in mice experiencing nicotine withdrawal. However, because of a change in the manufacturer’s thyroid ELISA kit, we could not directly compare the initial data demonstrating a nicotine withdrawal deficit in T4 levels with the data from a follow-up study examining if levothyroxine increased T4 levels in mice withdrawn from chronic nicotine and therefore it is unclear if levothyroxine led to a partial or full reversal of the nicotine withdrawal-induced decrease in T4. Nonetheless, nicotine withdrawal decreased T4 levels and levothyroxine increased T4 levels in mice withdrawn from chronic nicotine treatment. This indicates that changes in thyroid function should be monitored in smokers attempting to quit. Short-term thyroid hormone supplementation is a possible therapeutic option, previously unexplored, that may boost the efficacy of smoking cessation pharmacotherapies.

Funding

The authors received grant support from NIH-NIDA (TJG, DA024747, DA014949) and NIH-NIDA training fellowship through the Department of Pharmacology at Temple University (PTL, DA007237).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank G. Savulionyte for her technical support in the completion of these studies.

References

- 1. Kapoor D, Jones TH. Smoking and hormones in health and endocrine disorders. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tweed JO, Hsia SH, Lutfy K, Friedman TC. The endocrine effects of nicotine and cigarette smoke. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blanco-Muñoz J, Lacasaña M, Aguilar-Garduño C. Effect of current tobacco consumption on the male reproductive hormone profile. Sci Total Environ. 2012;426:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soldin OP, Makambi KH, Soldin SJ, O’Mara DM. Steroid hormone levels associated with passive and active smoking. Steroids. 2011;76:653–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Soldin OP, Goughenour BE, Gilbert SZ, Landy HJ, Soldin SJ. Thyroid hormone levels associated with active and passive cigarette smoking. Thyroid. 2009;19:817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sepkovic DW, Haley NJ, Wynder EL. Thyroid activity in cigarette smokers. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:501–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanderver GB, Engel A, Lamm S. Cigarette smoking and iodine as hypothyroxinemic stressors in U.S. women of childbearing age: a NHANES III analysis. Thyroid. 2007;17:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fukata S, Kuma K, Sugawara M. Relationship between cigarette smoking and hypothyroidism in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest. 1996;19:607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlé A, Bülow Pedersen I, Knudsen N, et al. Smoking cessation is followed by a sharp but transient rise in the incidence of overt autoimmune hypothyroidism - a population-based, case-control study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77:764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crown S. Notes on an experimental study of intellectual deterioration. Br Med J. 1949;2:684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dugbartey AT. Neurocognitive aspects of hypothyroidism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haggerty JJ, Jr, Evans DL, Prange AJ., Jr Organic brain syndrome associated with marginal hypothyroidism. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mennemeier M, Garner RD, Heilman KM. Memory, mood and measurement in hypothyroidism. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1993;15:822–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Osterweil D, Syndulko K, Cohen SN, et al. Cognitive function in non-demented older adults with hypothyroidism. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whybrow PC, Prange AJ, Jr, Treadway CR. Mental changes accompanying thyroid gland dysfunction. A reappraisal using objective psychological measurement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1969;20:48–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christensen SB, Ericsson UB, Janzon L, Tibblin S, Melander A. Influence of cigarette smoking on goiter formation, thyroglobulin, and thyroid hormone levels in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;58:615–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ericsson UB, Lindgärde F. Effects of cigarette smoking on thyroid function and the prevalence of goitre, thyrotoxicosis and autoimmune thyroiditis. J Intern Med. 1991;229:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fisher CL, Mannino DM, Herman WH, Frumkin H. Cigarette smoking and thyroid hormone levels in males. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:972–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jorde R, Sundsfjord J. Serum TSH levels in smokers and non-smokers. The 5th Tromsø study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114:343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bertelsen JB, Hegedüs L. Cigarette smoking and the thyroid. Thyroid. 1994;4:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schlienger JL, Grunenberger F, Vinzio S, Goichot B. [Smoking and the thyroid]. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2003;64:309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wiersinga WM. Smoking and thyroid. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;79:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flouris AD, Metsios GS, Jamurtas AZ, Koutedakis Y. Sexual dimorphism in the acute effects of secondhand smoke on thyroid hormone secretion, inflammatory markers and vascular function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E456–E462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Metsios GS, Flouris AD, Jamurtas AZ, et al. A brief exposure to moderate passive smoke increases metabolism and thyroid hormone secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alvarez MA, Gómez A, Alavez E, Navarro D. Attention disturbance in Graves’ disease. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1983;8:451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stern RA, Robinson B, Thorner AR, Arruda JE, Prohaska ML, Prange AJ., Jr A survey study of neuropsychiatric complaints in patients with Graves’ disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trzepacz PT, McCue M, Klein I, Greenhouse J, Levey GS. Psychiatric and neuropsychological response to propranolol in Graves’ disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:678–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yudiarto FL, Muliadi L, Moeljanto D, Hartono B. Neuropsychological findings in hyperthyroid patients. Acta Med Indones. 2006;38:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davis JD, Tremont G. Neuropsychiatric aspects of hypothyroidism and treatment reversibility. Minerva Endocrinol. 2007;32:49–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Biasi M, Dani JA. Reward, addiction, withdrawal to nicotine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:105–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Effects of nicotine in experimental animals and humans: an update on addictive properties. Handb Exp Pharmacol.2009;192:335–367. 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pieraccini G, Furlanetto S, Orlandini S, et al. Identification and determination of mainstream and sidestream smoke components in different brands and types of cigarettes by means of solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1180:138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Erdogan MF. Thiocyanate overload and thyroid disease. Biofactors. 2003;19:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gould TJ, Leach PT. Cellular, molecular, and genetic substrates underlying the impact of nicotine on learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;107108–132. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Modulation of hippocampus-dependent learning and synaptic plasticity by nicotine. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38:101–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184:523–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gould TJ, Collins AC, Wehner JM. Nicotine enhances latent inhibition and ameliorates ethanol-induced deficits in latent inhibition. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gould TJ, Feiro O, Moore D. Nicotine enhances trace cued fear conditioning but not delay cued fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice. Behav Brain Res. 2004;155:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gould TJ, Wehner JM. Nicotine enhancement of contextual fear conditioning. Behav Brain Res. 1999;102:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kenney JW, Adoff MD, Wilkinson DS, Gould TJ. The effects of acute, chronic, and withdrawal from chronic nicotine on novel and spatial object recognition in male C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;217:353–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leach PT, Cordero KA, Gould TJ. The effects of acute nicotine, chronic nicotine, and withdrawal from chronic nicotine on performance of a cued appetitive response. Behav Neurosci. 2013;127:303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wagner M, Schulze-Rauschenbach S, Petrovsky N, et al. Neurocognitive impairments in non-deprived smokers–results from a population-based multi-center study on smoking-related behavior. Addict Biol. 2013;18:752–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Davis JA, James JR, Siegel SJ, Gould TJ. Withdrawal from chronic nicotine administration impairs contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8708–8713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gould TJ, Wilkinson DS, Yildirim E, Blendy JA, Adoff MD. Dissociation of tolerance and nicotine withdrawal-associated deficits in contextual fear. Brain Res. 2014;1559:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patterson F, Jepson C, Loughead J, et al. Working memory deficits predict short-term smoking resumption following brief abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:61–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rukstalis M, Jepson C, Patterson F, Lerman C. Increases in hyperactive-impulsive symptoms predict relapse among smokers in nicotine replacement therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davis JA, Gould TJ. Atomoxetine reverses nicotine withdrawal-associated deficits in contextual fear conditioning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2011–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davis JA, Gould TJ. Hippocampal nAChRs mediate nicotine withdrawal-related learning deficits. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:551–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Portugal GS, Gould TJ. Bupropion dose-dependently reverses nicotine withdrawal deficits in contextual fear conditioning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;88:179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ray R, Rukstalis M, Jepson C, et al. Effects of atomoxetine on subjective and neurocognitive symptoms of nicotine abstinence. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Raybuck JD, Portugal GS, Lerman C, Gould TJ. Varenicline ameliorates nicotine withdrawal-induced learning deficits in C57BL/6 mice. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:1166–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Turner JR, Castellano LM, Blendy JA. Parallel anxiolytic-like effects and upregulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors following chronic nicotine and varenicline. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turner JR, Wilkinson DS, Poole RL, Gould TJ, Carlson GC, Blendy JA. Divergent functional effects of sazetidine-a and varenicline during nicotine withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2035–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wilkinson DS, Turner JR, Blendy JA, Gould TJ. Genetic background influences the effects of withdrawal from chronic nicotine on learning and high-affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptor binding in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;225:201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fu AL, Zhou CY, Chen X. Thyroid hormone prevents cognitive deficit in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smith JW, Evans AT, Costall B, Smythe JW. Thyroid hormones, brain function and cognition: a brief review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Le Traon G, Burgaud S, Horspool LJ. Pharmacokinetics of total thyroxine in dogs after administration of an oral solution of levothyroxine sodium. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. AbbVie. SYNTHROID® (levothyroxine sodium tablets, USP) product insert 2012. https://www.synthroid.com/. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 59. Gould TJ, Portugal GS, André JM, et al. The duration of nicotine withdrawal-associated deficits in contextual fear conditioning parallels changes in hippocampal high affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptor upregulation. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:2118–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hatsukami D, Fletcher L, Morgan S, Keenan R, Amble P. The effects of varying cigarette deprivation duration on cognitive and performance tasks. J Subst Abuse. 1989;1:407–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mortoglou A, Candiloros H. The serum triiodothyronine to thyroxine (T3/T4) ratio in various thyroid disorders and after Levothyroxine replacement therapy. Hormones (Athens). 2004;3:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kenney JW, Florian C, Portugal GS, Abel T, Gould TJ. Involvement of hippocampal jun-N terminal kinase pathway in the enhancement of learning and memory by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Logue SF, Paylor R, Wehner JM. Hippocampal lesions cause learning deficits in inbred mice in the Morris water maze and conditioned-fear task. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Portugal GS, Wilkinson DS, Kenney JW, Sullivan C, Gould TJ. Strain-dependent effects of acute, chronic, and withdrawal from chronic nicotine on fear conditioning. Behav Genet. 2012;42:133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baldi E, Lorenzini CA, Bucherelli C. Footshock intensity and generalization in contextual and auditory-cued fear conditioning in the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;81:162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Raybuck JD, Gould TJ. Nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits in trace fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice–a role for high-affinity beta2 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Prinz PN, Scanlan JM, Vitaliano PP, et al. Thyroid hormones: positive relationships with cognition in healthy, euthyroid older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M111–M116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Alzoubi KH, Aleisa AM, Gerges NZ, Alkadhi KA. Nicotine reverses adult-onset hypothyroidism-induced impairment of learning and memory: behavioral and electrophysiological studies. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:944–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Alzoubi KH, Gerges NZ, Aleisa AM, Alkadhi KA. Levothyroxin restores hypothyroidism-induced impairment of hippocampus-dependent learning and memory: behavioral, electrophysiological, and molecular studies. Hippocampus. 2009;19:66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Axelstad M, Hansen PR, Boberg J, et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of propylthiouracil (PTU) in rats: relationship between transient hypothyroxinemia during development and long-lasting behavioural and functional changes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ge JF, Peng L, Hu CM, Wu TN. Impaired learning and memory performance in a subclinical hypothyroidism rat model induced by hemi-thyroid electrocauterisation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Samuels MH, Schuff KG, Carlson NE, Carello P, Janowsky JS. Health status, mood, and cognition in experimentally induced subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2545–2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yin JJ, Liao LM, Luo DX, et al. Spatial working memory impairment in subclinical hypothyroidism: an FMRI study. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;97:260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhu DF, Wang ZX, Zhang DR, et al. fMRI revealed neural substrate for reversible working memory dysfunction in subclinical hypothyroidism. Brain. 2006;129:2923–2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Correia N, Mullally S, Cooke G, et al. Evidence for a specific defect in hippocampal memory in overt and subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3789–3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Patterson F, Jepson C, Strasser AA, et al. Varenicline improves mood and cognition during smoking abstinence. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:144–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]