Abstract

Feasibility and inter-session repeatability of cold and mechanical quantitative sensory testing (QST) were assessed in 24 normal dogs. Cold thermal latencies were evaluated using a thermal probe (0 °C) applied to three pelvic limb sites. Mechanical thresholds were measured using an electronic von Frey anesthesiometer (EVF) and a blunt-probed pressure algometer (PA) applied to the dorsal aspect of the metatarsus. All QST trials were performed with dogs in lateral recumbency. Collection of cold QST data was easy (feasible) in 19/24 (79%) dogs. However, only 18.4%, 18.9% and 13.2% of cold QST trials elicited a response at the medial tibia, third digital pad and plantar metatarsal regions, respectively. Collection of mechanical QST data was easy (feasible) in 20/24 (83%) dogs for both EVF and PA.

At consecutive sampling times, approximately 2 weeks apart, the average EVF sensory thresholds were 414 ± 186 g and 379 ± 166 g, respectively, and the average PA sensory thresholds were 1089 ± 414 g and 1028 ± 331 g, respectively. There was no significant difference in inter-session or inter-limb threshold values for either mechanical QST device. The cold QST protocol in this study was achievable, but did not provide consistently quantifiable results. Both mechanical QST devices tested provided repeatable, reliable sensory threshold measurements in normal, client-owned dogs. These findings contribute to the validation of the EVF and PA as tools to obtain repeated QST data over time in dogs to assess somatosensory processing changes.

Keywords: Canine, Quantitative sensory testing, Pressure algometer, Electronic von Frey anesthesiometer

Introduction

Pain is a highly complex sensation, which is ineradicably linked to quality of life in human beings and veterinary species. As such, assessment of acute and chronic pain is vital, yet challenging. In veterinary medicine, our ability to accurately and reliably assess pain is limited by the lack of quantitative and thoroughly validated tools for its measurement (Sharkey, 2013). Furthermore, chronic pain, such as that associated with osteoarthritis (OA), can be complicated by long-term changes in dorsal horn neurons, resulting in central sensitization (CS) and ‘pathologic pain’ (Woolf, 2007; Gwilym et al., 2009; Graven-Nielsen and Arendt-Nielsen, 2010).

Studies using psychophysical testing, known as quantitative sensory testing (QST), indicate that OA is associated with CS, manifested as allodynia and hyperalgesia both at local and distant sites (Kosek and Ordeberg, 2000; Bajaj et al., 2001; Arendt-Nielsen et al., 2010). Perhaps most importantly, the presence of hyperalgesia in human beings with OA correlates with higher pain intensity, higher disability scores and poorer quality of life (Imamura et al., 2008). Human clinical data show that pain-induced neuroplasticity can result in both facilitated and decreased sensory processing (hyperalgesia and hypoalgesia, respectively), depending on the type of stimulus being investigated, where it is applied and the pain condition (Wylde et al., 2011a).

Due to growing support for QST as a valid, semi-objective component of comprehensive pain evaluation in human beings, the development of similar approaches is warranted in veterinary medicine. Cold or mechanical QST has been used in dogs by Brydges et al. (2012) and Moore et al. (2013), but these studies did not evaluate the feasibility or repeatability of these modalities in normal dogs. The aim of the present study was to assess the feasibility and inter-session repeatability of (1) mechanical sensory thresholds using an electronic von Frey anesthesiometer (EVF) and a blunt-probed pressure algometer (PA); and (2) cold thermal sensory thresholds using a thermal probe, with all devices applied to the pelvic limb of dogs in lateral recumbency.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

Dogs were evaluated at two appointments, approximately 2 weeks apart. At appointment 1, dogs were tested using three instruments (cold probe, EVF and PA). At appointment 2, dogs were tested using the two mechanical devices only, due to a lack of response to the cold thermal stimulus at appointment 1. Prior to testing, dogs were acclimated to a quiet room (gait laboratory), with minimal distractions, for 10 min. Dogs were allowed to explore the environment without restraint during that time. After acclimating, dogs were placed in lateral recumbency with gentle, minimum restraint, on a 1.5 cm thick, 2.4 m by 3.0 m house rug, to begin data collection.

To measure thresholds on the left pelvic limb, dogs were placed in right lateral recumbency, and vice versa for the right pelvic limb. The order of device and limb to be tested were randomized prior to testing using the coin toss method. All QST trials were applied and timed by the same operators.

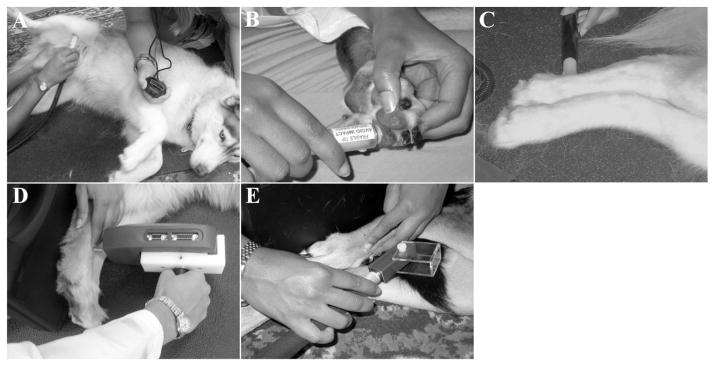

Cold stimuli were applied to three unclipped pelvic limb sites for testing, namely, the medial tibia, third digital pad and plantar metatarsal region (Fig. 2A–C). The cold thermal probe was applied at 0 °C until a behavioral response was elicited or the cut-off time of 60 s was reached. The latency to respond was measured in seconds for each site using a digital stopwatch measuring to 0.01 s, with five trials per limb and 1 min of rest allowed between measurements.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative sensory testing sites used in this study. Cold stimuli were applied to three pelvic limb sites for testing: medial tibia (A), third digital pad (B) and plantar metatarsal region (C). Mechanical stimuli were applied to the dorsal surface of the metatarsus, between metatarsal bones III and IV, using a blunt-probed pressure algometer (D) and an electronic von Frey anesthesiometer (E).

The EVF and PA were applied with steadily increasing force, perpendicular to the dorsal surface of the metatarsus, between metatarsal bones III and IV, approximately halfway between the tarsometatarsal and metatarsophalangeal joints, as described previously (Moore et al., 2013) (Fig. 2D and E). For support, a flat, inflexible surface was placed behind the paw while mechanical stimuli were applied. The operator applying the device was not permitted to view the force value until a behavioral response was elicited. The force at retraction for both devices was measured in grams (g), with five trials per limb and 1 min rest allowed between measurements.

For both cold thermal and mechanical stimuli, the end-point was defined as a deliberate movement of the limb away from the probe, turning to look at the site, vocalization or when the maximum force of the instrument was reached. Each dog was assigned a feasibility score that described the ease with which data could be collected for each device. Feasibility was based on a scale from 0 to 5 (Table 1), with scores ranging from 0 to 2 considered to be ‘easy data collection’ and those from 3 to 5 considered to be ‘difficult data collection’. For all QST devices, dogs scoring >2 were not allowed to return for the second evaluation and were excluded from analysis due to the lack of a full data set.

Table 1.

Feasibility scoring rubric for evaluation of the ease with which quantitative sensory testing data could be collected from dogs.

| Feasibility score | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 – No problem | Minimum restraint needed; excellent cooperation; clear reaction to stimuli |

| 1 – Mild difficulty | Mild restraint needed; good cooperation; clear reaction to stimuli |

| 2 – Moderate difficulty | Moderate restraint needed; good cooperation >50% of the time; mild sensitivity of feet being touched; mild variation in reaction to stimuli |

| 3 – Significant difficulty | Significant restraint needed and resisted lateral recumbency; good cooperation <25% of the time; moderate sensitivity to feet being touched; moderate variation in reaction to stimuli |

| 4 – Extreme difficulty | Constant restraint required; not cooperative; unclear reaction to stimuli, not confident in data collected |

| 5 – Impossible | Could not collect data due to the dog’s disposition and/or lack of confidence in the reactions seen being due to the stimulus |

Animals

Twenty-four normal, client-owned dogs were recruited via e-mail and flyers within the veterinary college community. To be included in the study, dogs had to be older than approximately 2 years of age and weigh between 10 and 40 kg. Owners completed a clinical metrology instrument, the Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI), to assess pain and quality of life (Brown et al., 2007). The CBPI was completed at both appointments to ensure that no significant changes occurred over time. Inclusion criteria were mean CBPI scores <0.75 per question for pain intensity and pain interference, with quality of life scores ≥4 (very good) (Brown et al., 2007).

Dogs were further screened by medical history review, physical examination, full orthopedic examination, complete blood count and biochemistry profiles. Orthopedic examination evaluated gait (lameness, stiffness and posture), joint manipulation (range of motion, pain, crepitus, joint effusion and thickening of the joint capsule) and muscle atrophy. To be included, dogs had to be judged by the examiner to be free of clinically detectable orthopedic, neurologic or other systemic disease, to have no evidence of pain or mobility impairment for any reason and not be receiving anti-inflammatory or other analgesic drugs. The physical and orthopedic examinations were repeated at the second appointment to ensure that no changes had occurred between appointments.

The study was approved by the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 11-073-0, date of approval 23 May 2012). Owners were required to sign a consent agreement for enrollment.

Devices

Cold stimuli were applied using a handheld thermal probe (NTE-2A, Physitemp Instruments) with a 13 mm diameter surface set at 0 ± 0.1 °C (Fig. 1A). The probe used a Peltier semiconductor heat pump and digital temperature control unit to maintain accurate temperature application during trials.

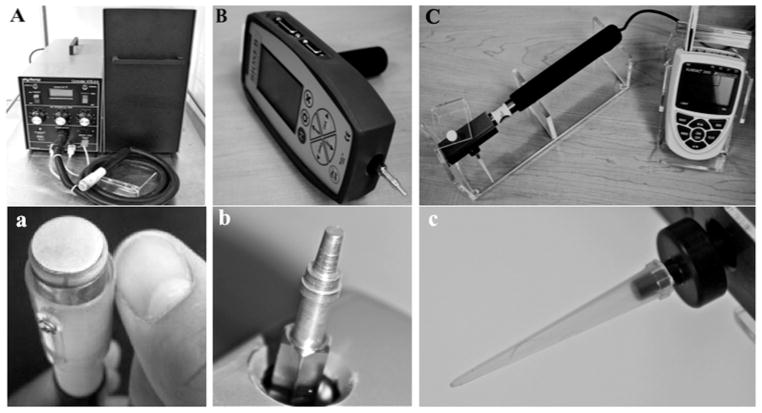

Fig. 1.

(A) Handheld thermal probe device with cable, temperature control unit with recirculating pump and water reservoir. (a) Close-up of thermal probe tip. (B) Blunt-probed pressure algometer (PA) with flat tip attached to recording unit. (b) Close-up of PA tip. (C) Electronic von Frey (EVF) anesthesiometer with load cell, attached rigid tip and recording device. (c) Close-up of EVF tip.

Two devices were used to apply distinct mechanical stimuli. The blunt-probed pressure algometer (SMALGO, Bioseb) was equipped with a flat, 3mm diameter tip attached to a recording unit (Fig. 1B). The unit sampled at 1000 Hz, with an accuracy of 0.2%, a resolution of 0.1 g and a capacity of 1500 g. The integrated software recorded the maximum force applied to the test site. The electronic von Frey device (IITC Life Science) was equipped with a 1000 g internal load cell and an attached, modified pipette tip for application of the stimulus. The diameter of the pipette tip was 0.5 mm. The load cell was connected to an electronic recording device that measured and displayed the maximum force applied to the test site, with a resolution of 0.1 g (Fig. 1C).

Statistical analysis

Mechanical threshold results are reported as means ± standards deviations (SDs), excluding all first trial values for each limb at each appointment, since on initial data analysis they accounted for approximately 40% of all points deviating more than 1.5 times the inter-quartile range and were considered to be outliers. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to assess the effects of the independent variables dog, bodyweight, age, sex, appointment, limb and trial. Repeatability of mechanical QST thresholds across appointment and limb was assessed using Wilcoxon tests. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to assess correlation between mechanical thresholds and clinical parameters. A standard least squares leverage effect analysis was used to evaluate inter-individual variance. For all data analysis, P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Twenty-four normal, client-owned dogs, representing eight breeds, were recruited. The group consisted of 11 spayed females, one intact female, 11 castrated males and one intact male. The mean age of the group was 5.5 ± 3.5 years (range 1.8–13.1 years) and the mean bodyweight was 23.0 ± 8.0 kg (range: 13.9–40.3 kg). The median CBPI scores, across both appointments, were 0 (pain intensity), 0 (pain interference) and 5 (quality of life).

Feasibility

Distribution of feasibility scores at appointment 1 (n = 24), for both the EVF and PA mechanical QST were 20/24 (83%) scoring 0–2 (easy data collection) and 4/24 (17%) scoring 3–5 (difficult data collection) (Table 2). At appointment 2, all dogs evaluated (n = 20) had feasibility scores of 0–2 for both mechanical devices. The cold probe feasibility was only tested at appointment 1 (n = 24) and the distribution of feasibility scores was 19/24 (79%) scoring 0–2 and 5/24 (21%) scoring 3–5. For all QST, dogs scoring >2 did not return for the second evaluation and thus were excluded from the analysis; such dogs needed significant restraint to remain in lateral recumbency, were sensitive to having their feet touched by the operator or did not exhibit clear reactions to QST stimuli. Dogs that were excluded due to feasibility scores did not differ significantly in age (mean 4.6 ± 1.6 years; range 1.8–5.9 years) or weight (mean 24.4 ± 10.3 kg; range 16.1–40.3 kg).

Table 2.

Feasibility scores for cold and mechanical quantitative sensory testing (QST).

| Easy

|

Difficult

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | Total | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | |

| Electric von Frey anesthesiometer | ||||||||

| Appointment 1 (n = 24) | 11 (46%) | 7 (29%) | 2 (8%) | 20 (83%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) | 4 (17%) |

| Appointment 2 (n = 20)a | 15 (75%) | 2 (10%) | 3 (15%) | 20 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pressure algometer | ||||||||

| Appointment 1 (n = 24) | 12 (50%) | 6 (25%) | 2 (8%) | 20 (83%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) | 4 (17%) |

| Appointment 2 (n = 20)a | 15 (75%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (10%) | 20 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cold probe | ||||||||

| Appointment 1 (n = 24) | 12 (50%) | 5 (21%) | 2 (8%) | 19 (79%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (21%) | 5 (21%) |

For all QST, dogs scoring >2 were excluded from analysis due to the difficulty in collecting data and not being able to collect a full data set. These dogs did not return for the second evaluation.

Electronic von Frey anesthesiometer

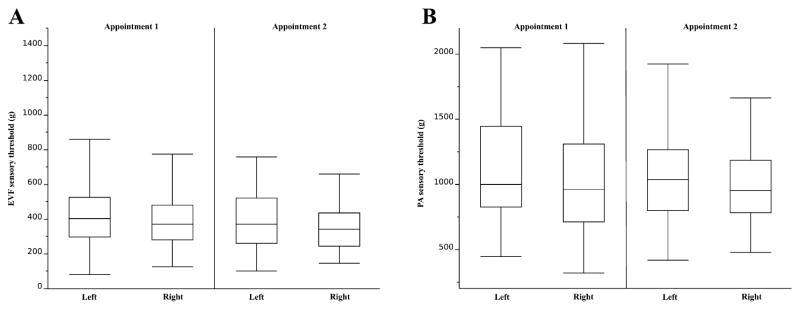

The average EVF sensory thresholds for the right and left limbs at appointment 1 were 390 ± 162 g (19,136 ± 7958 kPa) and 438 ± 206 g (21,492 ± 10,050 kPa), respectively; averages at appointment 2 were 359 ± 140 g (17,617 ± 6845 kPa) and 399 ± 187 g (19,569 ± 9182 kPa), respectively (Table 3; Fig. 3A). There was no difference between the measurements taken from the right or left limb at either appointment (appointment 1: P = 0.13; appointment 2: P = 0.18). Furthermore, there was no inter-session difference in thresholds (right: P = 0.36; left: P = 0.33).

Table 3.

Mean sensory threshold values (±standard deviations) measured in grams (g) in normal dogs for each pelvic limb.

| Device | Pelvic limb | Appointment 1 | Appointment 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic von Frey anesthesiometer | Right | 390 ± 162 | 359 ± 140 |

| Left | 438 ± 206 | 399 ± 187 | |

| Pressure algometer | Right | 1048 ± 425 | 959 ± 282 |

| Left | 1131 ± 401 | 1070 ± 371 |

Fig. 3.

(A) Electronic von Frey (EVF) and (B) pressure algometer (PA) mean sensory thresholds (±standard deviations) in normal dogs for each pelvic limb at appointments 1 and 1 (n = 20).

The coefficient of variation for EVF measurements was 45%, with inter-individual differences accounting for 33% of variance. The MANOVA showed effects on EVF thresholds by dog (P < 0.0001), but no effect by limb (P = 0.15), appointment (P = 0.24), trial (P = 0.91), age (P = 0.68), sex (P = 0.37) or weight (P = 0.052). Measured thresholds had a significant, weak correlation with bodyweight (ρ = 0.21, P = 0.0001).

Blunt-probed pressure algometer

The average PA sensory thresholds for the right and left limbs at appointment 1 were 1048 ± 425 g (1454 ± 589 kPa) and 1131 ± 401 g (1568 ± 556 kPa), respectively; averages at appointment 2 were 959 ± 282 g (1367 ± 391 kPa) and 1070 ± 371 g (1484 ± 514 kPa), respectively (Table 3; Fig. 3B). There was no difference between the measurements taken from the right or left limb at either appointment (appointment 1: P = 0.12; appointment 2: P = 0.11). Furthermore, there was no inter-session difference in thresholds (right: P = 0.45; left: P = 0.36).

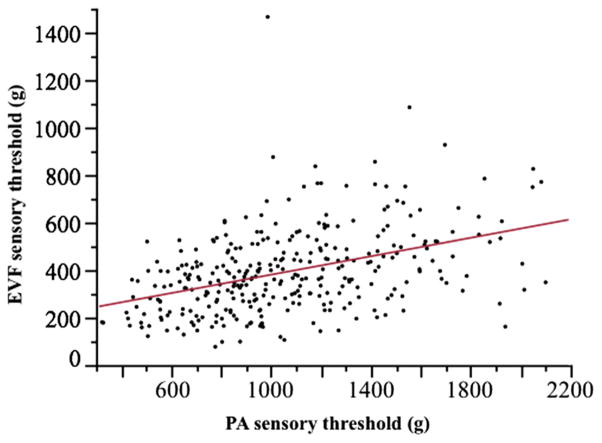

The coefficient of variation for PA measurements was 35%, with inter-individual differences accounting for 44% of variance. MANOVA for PA thresholds showed an effect by dog (P < 0.0001) and weight (P < 0.0001), but not by limb (P = 0.18), appointment (P = 0.32), trial (P = 0.067), age (P = 0.094) or sex (P = 0.15) (Table 4). Measured thresholds had a significant, weak correlation with bodyweight (ρ = 0.42, P < 0.0001) and age (ρ = −0.14, P = 0.0145). In addition, thresholds were significantly different across the mechanical devices (P < 0.0001) and were significantly correlated (ρ = 0.42, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4).

Table 4.

MANOVA analysis evaluating factors that influenced electronic von Frey (EVF) anesthesiometer and pressure algometer (PA) quantitative sensory testing values in normal dogs.

| Factor | Electronic von Frey (EVF) anesthesiometer | Pressure algometer (PA) |

|---|---|---|

| Dog | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.052 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 0.68 | 0.094 |

| Sex | 0.37 | 0.15 |

| Appointment | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| Limb | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Trial | 0.91 | 0.067 |

Fig. 4.

Linear fit of electronic von Frey (EVF) sensory threshold against pressure algometer (PA) sensory threshold. R2 = 0.17; ρ = 0.42, P < 0.0001.

Cold quantitative sensory testing

Five tests per limb were performed at each cold QST site (n = 19), for a total of 190 tests per site. The number of tests eliciting a response prior to the 60 s cut-off for the medial tibia, third digital pad and plantar metatarsal region were 35/190 (18.4%), 36/190 (18.9%) and 25/190 (13.2%), respectively; for tests that elicited a response, the average latency was 17.81, 16.72 and 25.25 s, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cold quantitative sensory testing response and latency results in normal dogs.

| Site | Limb | % Tests eliciting response | Average latency (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial tibia (n = 19) | Right | 23/95 (24.2%) | 16.91 |

| Left | 12/95 (12.6%) | 18.70 | |

| Both | 35/190 (18.4%) | 17.81 | |

| Third digital pad (n = 19) | Right | 18/95 (18.9%) | 14.14 |

| Left | 18/95 (18.9%) | 19.29 | |

| Both | 36/190 (18.9%) | 16.72 | |

| Plantar metatarsal (n = 19) | Right | 11/95 (11.6%) | 26.20 |

| Left | 14/95 (14.7%) | 24.30 | |

| Both | 25/190 (13.2%) | 25.25 |

Discussion

The cold and mechanical QST protocol described here was easy to execute and well tolerated by the majority of dogs recruited. Repeatability in this cohort of normal dogs appeared to be good, suggesting that evaluation of these methods in diseased dogs should be investigated. The feasibility and repeatability of mechanical QST mirrors the feasibility of thermal hot QST recently found in a separate cohort of dogs (Williams et al., 2014). The clinical metrology instrument (CBPI) used in the present study allowed for subjective owner assessment of pain to ensure inclusion of normal dogs. Criteria for mean CBPI scores per question were derived from previously determined score ranges in normal dogs (Brown et al., 2007). CBPI criteria were further supported by thorough physical, orthopedic and neurological evaluations to ensure that the dogs were normal.

The subjective feasibility scores in this study suggest that the QST protocol described here represents a feasible tool for somatosensory assessment in at least 79% of dogs that are untrained in these procedures. Since data analysis only included dogs in which data collection was ‘easy’, evaluation of repeatability may be biased. However, we believe that this is justified by the need for full data sets if this tool is to be used as an outcome measure in a clinical trial or as an assessment tool in case management. Other investigators (Moore et al., 2013) have used dog appeasement pheromone (DAP) for similar studies, which may have affected data collection. Future studies should evaluate the effect of DAP on testing sensory thresholds.

Moore et al. (2013) tested sensory thresholds of the distal pelvic limb in dogs in lateral recumbency. We have found that dogs with OA, or other orthopedic or neurologic dysfunction, may shift their weight frequently, have trouble standing for long periods of time or have trouble sitting and rising repeatedly (unpublished observations), making lateral recumbency a more suitable position for QST across disciplines. However, Brydges et al. (2012) successfully performed mechanical QST in standing dogs suffering from unilateral cruciate ligament rupture.

Cold thermal QST did not provide quantifiable results in most tests in our study. The most successful testing site was the third digital pad, with 19% of tests eliciting a response. Similar findings were reported in a human study, where cold pain thresholds using a gradually decreasing probe temperature were not obtained before the safety cut-off temperature of 5 °C (Wylde et al., 2011b). It is possible that better results may be obtained by applying a negatively ramped temperature, paralleling ramped hot thermal stimuli (Wegner et al., 2008). Cold thermal testing was successfully employed by Brydges et al. (2012) in dogs standing on a cold plate and measuring the time they remained on the cold plate vs. a plate at ambient temperature.

Mechanical sensory thresholds for both devices had significant positive correlations with weight, as previously described in a smaller population of healthy dogs by Moore et al. (2013). However, given the relatively low correlation coefficients (EVF, ρ = 0.21; PA, ρ = 0.42), we feel that the data from the present study do not support scaling raw thresholds to bodyweight within a relatively confined weight range. It may be necessary to further explore this relationship in larger QST studies. In addition, a correlation was found between age and PA sensory thresholds, with older dogs exhibiting increased sensitivity to stimuli, despite being deemed free of pain. This relationship should be borne in mind as a confounding variable in future QST studies, since age-related changes in the somatosensory system have yet to be fully elucidated (Yezierski, 2012).

In the cohort evaluated in this study, there was a moderate coefficient of variation for mechanical thresholds, with the PA measurements exhibiting lower variance. Given that a large proportion of the variance was due to differences among dogs, this finding makes it challenging to establish normative data ranges of sensory thresholds without a much larger sample size, as has been done in human medicine (Rolke et al., 2006). However, similar to studies in human beings, mechanical QST repeatability was good when comparing data within individual dogs (Moss et al., 2007; Wylde et al., 2011b). These results are supportive for the use of intra-individual reference data in patients for clinical evaluation of sensory function over time.

However, clinical QST results should be taken into consideration as a part of a complete, multimodal somatosensory and musculoskeletal evaluation (Hansson et al., 2007). We believe that there will be utility in assessing mechanical QST over time within individual dogs for the evaluation of therapies. However, the fundamental question of whether or not QST values differ between normal dogs and dogs in chronic pain will need to be fully explored.

The relationships between probe surface area and the force required to obtain a response has not been investigated in veterinary medicine. In the present study, mean sensory thresholds expressed as pressure were significantly different across devices, but exhibited significant positive correlations. Mean EVF pressure thresholds were higher than those measured with the PA; the EVF providing a pointed stimulus, whereas the PA probe is blunt. Future studies should evaluate the ability of devices to detect CS. For example, EVF may provide better detection of CS due to its hypothesized preferential testing of Aβ axons (Walk et al., 2009).

Conclusions

The cold QST protocol in this study was feasible, but did not provide consistently quantifiable results. Both mechanical QST devices tested were highly feasible and provided repeatable, reliable sensory threshold measurements in normal, client-owned dogs. These findings contribute to the validation of the EVF and PA as tools to obtain repeated QST data over time in dogs.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Comparative Pain Research Laboratory at the North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine (instruments) and Boeringher Ingelheim Vetmedica (screening of dogs). J.D. Briley received stipend support through the Merial Veterinary Scholars program and Ms. Deborah Resnick. M.D. Williams received stipend support from the NIH/T35 Interdisciplinary Biomedical Research Program. M. Freire received Fellowship salary support from the Morris Animal Foundation. Preliminary results were presented as a poster at the Merial-NIH National Veterinary Scholars Symposium, Colorado State University, Colorado, USA, 2–5 August 2012, and as an oral presentation at the North Carolina State University Research Forum, Raleigh, North Carolina, 20 February 2013.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

B.D.X. Lascelles has acted as a paid consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica and has received payment for continuing education lectures. None of the other authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organisations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

References

- Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2010;149:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj P, Bajaj P, Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Osteoarthritis and its association with muscle hyperalgesia: An experimental controlled study. Pain. 2001;93:107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DC, Boston RC, Coyne JC, Farrar JT. Development and psychometric testing of an instrument designed to measure chronic pain in dogs with osteoarthritis. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 2007;68:631–637. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.68.6.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydges NM, Argyle DJ, Mosley JR, Duncan JC, Fleetwood-Walker S, Clements DN. Clinical assessments of increased sensory sensitivity in dogs with cranial cruciate ligament rupture. The Veterinary Journal. 2012;193:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2010;6:599–606. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwilym SE, Keltner JR, Warnaby CE, Carr AJ, Chizh B, Chessell I, Tracey I. Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;61:1226–1234. doi: 10.1002/art.24837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson P, Backonja M, Bouhassira D. Usefulness and limitations of quantitative sensory testing: Clinical and research application in neuropathic pain states. Pain. 2007;129:256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura M, Imamura ST, Kaziyama HHS, Targino RA, Hsing WT, de Souza LPM, Cutait MM, Fregni F, Camanho GL. Impact of nervous system hyperalgesia on pain, disability, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A controlled analysis. Arthritis and Rheumatism – Arthritis Care and Research. 2008;59:1424–1431. doi: 10.1002/art.24120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek E, Ordeberg G. Abnormalities of somatosensory perception in patients with painful osteoarthritis normalize following successful treatment. European Journal of Pain. 2000;4:229–238. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Hettlich BF, Waln A. The use of an electronic von Frey device for evaluation of sensory threshold in neurologically normal dogs and those with acute spinal cord injury. The Veterinary Journal. 2013;197:216–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss P, Sluka K, Wright A. The initial effects of knee joint mobilization on osteoarthritic hyperalgesia. Manual Therapy. 2007;12:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolke R, Baron R, Maier C, Tolle TR, Treede RD, Beyer A, Binder A, Birbaumer N, Birklein F, Botefur IC, et al. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): Standardized protocol and reference values. Pain. 2006;123:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey M. The challenges of assessing osteoarthritis and postoperative pain in dogs. AAPS Journal. 2013;15:598–607. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9467-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walk D, Sehgal N, Moeller-Bertram T, Edwards RR, Wasan A, Wallace M, Irving G, Argoff C, Backonja MM. Quantitative sensory testing and mapping: A review of nonautomated quantitative methods for examination of the patient with neuropathic pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2009;25:632–640. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181a68c64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner K, Horais KA, Tozier NA, Rathbun ML, Shtaerman Y, Yaksh TL. Development of a canine nociceptive thermal escape model. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2008;168:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MD, Kirkpatrick AE, Griffith E, Benito J, Hash J, Lascelles BDX. Feasibility and repeatability of thermal quantitative sensory testing in normal dogs and dogs with hind limb osteoarthritis-associated pain. The Veterinary Journal. 2014;199:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Uncovering the relation between pain and plasticity. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:864–867. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264769.87038.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Palmer S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Somatosensory abnormalities in knee OA. Rheumatology. 2011a;51:535–543. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Palmer S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Test–retest reliability of quantitative sensory testing in knee osteoarthritis and healthy participants. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2011b;19:655–658. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yezierski RP. The effects of age on pain sensitivity: Preclinical studies. Pain Medicine. 2012;13:S27–S36. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]