Abstract

Background

Infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) remain important in solid organ transplantation. Quantitative viral nucleic acid testing is a major advance to patient management. These assays are limited by a lack of standardization, resulting in viral load measurements that differ among clinical laboratories. The variability in viral load measurements makes interpretation of multicenter clinical trials data difficult. This study compares the current practices in CMV and EBV viral load testing at four large transplant centers participating in multicenter Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation (CTOT/CTOTC).

Methods

Viral load testing was performed on well-defined viral preparations according to standard operating procedures at each site.

Results

Among centers, CMV viral load testing was accurate compared to WHO International Standards and within acceptable variation for this testing method. EBV viral load data were more variable and less accurate despite the use of international standards.

Conclusions

These data suggest that comparison of CMV, but not EBV, viral load measurements at these sites is possible using current assays and control standards. Standardization of these assays is facilitated by using the WHO International Standards and will allow comparison of viral load results among transplant centers. Assay standardization must be performed prior to initiation of multicenter trials.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, viral load, quantitative nucleic acid testing, WHO standards, clinical trial

Introduction

In transplant recipients, viral load testing has become the primary modality for diagnosing active disease due to cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infections and monitoring responses to therapy (1–7). Using whole blood or plasma, viral nucleic acid is extracted and subjected to amplification using quantitative, real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) based assays. The number of viral copies present in the initial sample is determined by comparison to a set of standards with known copy number. Until recently, there were no standardized materials for preparing these sets of standards. Thus, laboratories developed and validated testing protocols using calibrators that may or may not have been equivalent. Further, although the methodologies used for viral load testing may be similar from one laboratory to another, reagents, extraction methods, primers, and amplification platforms can vary from one clinical laboratory to another (8–14). This further contributes to assay variability making it problematic to compare results between laboratories (10,11).

Quantitative viral load testing for CMV and EBV provides a method to assess the intensity of immunosuppression and protocol safety in the setting of clinical trials, notably for studies of new immunosuppressive regimens or antiviral therapies. Given the lack of assay standardization, the interpretation of study data in terms of development of viral load cutoffs for the clinical diagnosis and management of CMV or EBV infection or EBV-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) has been challenging. The World Heath Organization (WHO) has developed assay standards for both CMV and EBV (15,16). These viral preparations are intended for use by laboratories and manufacturers to calibrate secondary reference materials, so that the concentration of virus in a sample can be expressed and compared in international units. The Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation (CTOT) and the Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation in Children (CTOT-C) are research consortia sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) that conduct clinical trials and associated mechanistic studies to improve outcomes in adult and pediatric organ transplantation. Given that viral monitoring is a routine component in the care of transplant recipients, this study was designed to compare the accuracy and variability of CMV and EBV viral load testing using the WHO viral standards in comparison to commonly used commercially available viral panels at four of the CTOT transplantation centers.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

CMV and EBV viral load testing was performed at four independent clinical laboratories from academic medical centers that are members of the Clinical Trials in Organ Transplant (CTOT) Mechanistic Studies Working Group (Cleveland Clinic, Emory Transplant Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Washington University School of Medicine). Each laboratory performed the assays according to center-specific standard operating procedures. All samples were tested blindly. Results were reported in copies per milliliter (ml). The procedural characteristics of the assay(s) used at each site are shown in Table 1 and described below. One site used two separate protocols for testing. All studies were approved by institutional review panels for human studies at each participating clinical center.

Table 1.

Testing Protocols

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Amplification and Detection | Target and Amplicon Size | Reportable Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QiAmp Virus on Qiagen BioRobot MDX | Qiagen artus TM EBV/CMV on Aplied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System | EBV EBNA1 Amplicon size: 97 bp CMV Major IE Amplicon size: 105 bp |

EBV 500–5,000,000 cp/ml CMV 313 – 3,130,000 cp/ml |

| 2 | QiAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit on QiaCube | Qiagen artus TM EBV/CMV on Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 12K Flex | EBV EBNA1 Amplicon size: 97 bp CMV Major IE Amplicon size: 105 bp |

EBV >25 cp/ml CMV >50 cp/ml |

| 3 | Qiagen Virus/Bacteria Mini/Midi kit on QiaSymphony | Qiagen artus TM EBV/CMV on Qiagen RotorGene Q | EBV EBNA1 Amplicon size: 97 bp CMV Major IE Amplicon size: 105 bp |

EBV 300–1,500,000 cp/ml CMV 1000–5,000,000 |

| 4 | Qiagen MinElute kit on QiaCube | Primera Dx ViraQuant on ICEPlex | EBV EBNA-LP Amplicon size: 155 bp CMV US28 Amplicon size: 171 bp |

EBV 750–15,000,000 cp/ml CMV 750–15,000,000 cp/ml |

| 5 | MagNA Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit 1 on Roche MagNA Pure Compact | Lab developed assays on ABI 7500 Real-Time System (EBV) and ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (CMV) | EBNA1 Amplicon size: 68 bp CMV UL54 Amplicon size: 61 bp |

EBV 4,000–40,000,000 cp/ml CMV 2,000 – 1,250,000 cp/ml |

Quantitation Panels

For each virus and study site, one commercial panel and one panel created from the WHO International Standards were tested. These panels were chosen to represent the control materials that were already in use for verifying CMV and EBV test systems. They also allow the entire process from nucleic acid extraction to quantitation to be assessed since they consist of viral particles suspended in a plasma matrix. The CMV commercial panel consisted of a single replicate of five members from the OptiQuant CMVtc Panel from Acrometrix (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and a negative control consisting of dialyzed, defibrinated human plasma (BaseMatrix; SeraCare, Milford, MA). The OptiQuant CMVtc panel consists of human plasma containing CMV strain AD169. The manufacturer specified that the concentration of CMV DNA in each of the panel members was 500, 5000, 50,000 and 500,000 copies/ml. The CMV International Standard panel consisted of triplicate tenfold serial dilutions of the 1st WHO International Standard for Human Cytomegalovirus obtained from NIBSC (code 09/162; Hertfordshire, England). This preparation consists of lyophilized CMV Merlin strain and was assigned a potency of 5×106 IU/ml based on a worldwide collaborative evaluation in which the consensus value was 5×106 copies/ml (15). The lyophilized standard was reconstituted in 1 ml of nuclease free water and dilutions were prepared in dialyzed, defibrinated human plasma (BaseMatrix; SeraCare, Milford, MA) to achieve panel members spanning 50 to 500,000 copies/ml. A negative control consisting of BaseMatrix alone was included.

The EBV commercial panel consisted of a single replicate of all six members of the OptiQuant EBV Plasma Panel obtained from Acrometrix (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). This panel includes human plasma containing EBV ranging in concentration from 1000 to 10,000,000 copies/ml and a negative control. The EBV International Standard panel consisted of triplicate tenfold serial dilutions of the 1st WHO International Standard for EBV obtained from NIBSC (code 09/260; Hertfordshire, England). This preparation contains lyophilized EBV strain B95-8 and was assigned a potency of 5×106 IU/ml based on a worldwide collaborative evaluation in which the consensus value was 5×106 copies/ml (16). This standard was prepared in the same manner as the CMV International Standard and included panel members spanning 10 to 1,000,000 copies/ml and a negative control.

For all four panels, each panel component was assigned a code and relabeled to anonymize the source and remove any indication of the expected copy number. The quantitation panels were simultaneously frozen at −80 °C and shipped overnight on dry ice to each study site.

Viral Load Assays

Each laboratory performed CMV and EBV viral load testing on each of the panels as per institutional standard protocols for plasma as indicated in Table 1. One site performed two separate assays for both CMV and EBV testing including one standard and one multiplex assay system.

All of the extraction protocols involve sample lysis under denaturing conditions in the presence of protease. For protocols 2 and 4 the initial sample volume was 200ul. For protocol 1 initial sample volume was 263ul. For protocol 3, the initial sample volume was 500ul for CMV and 1000ul for EBV. For protocol 5, the initial sample volume was 200ul. In protocols 1, 2, and 4, nucleic acids are adsorbed onto a silica membrane, washed, and eluted into buffer. In protocols 3 and 5, magnetic beads rather than a silica membrane are used. The exact makeup of the reagent buffers is proprietary, but differs among the protocols. The elution volumes for protocols 3 and 4 were 60ul. For protocol 1, 2, and 5 the elution volume was 83ul, 50ul, and 100ul respectively.

The amplification and detection protocols are all based on real-time quantitative detection using fluorescent dyes linked to oligonucleotide probes. Protocols 1, 2, and 3 used the same amplification and detection kit, although on different thermocycling instruments (Table 1). Protocol 4 used the IcePlex system, which is a multiplex real-time PCR and capillary electrophoresis instrument. Protocol 5 used a lab-developed protocol and reagents on an ABI 7500 Real Time System. The volume of nucleic acid used in protocols 1, 2, and 3 was 20ul. Protocol 4 and 5 used an input volume of 10ul and 5ul for amplification.

Statistical Methods

Each viral load result was log10 transformed before analysis. Negative results and any result reported as positive but below the reportable range were not included in the calculation of mean and range.

Results

Testing Protocols

For CMV and EBV viral load testing, two quantitation panels for each virus were sent to each of the four transplantation sites for testing. All five protocols used automated nucleic acid extraction systems with either silica-membrane or magnetic bead based isolation of the viral DNA. However, the sample volume, elution volume, reagents, and extraction platforms differed for each protocol (Table 1). For CMV, three of the protocols targeted the Major Intermediate Early (IE) gene using the Qiagen artus CMV reagent kit, and amplification and detection was performed on three separate thermocycler platforms. The other two protocols (Primera Dx ViraQuant and a laboratory developed assay protocol) utilized primers targeting the US28 and UL54 genes. The reportable range for these protocols varied considerably among sites. For one assay, the lower limit for quantitation was 50 copies/ml while another assay had a lower limit of 2000 copies/ml. Similarly for EBV, three protocols used the same Qiagen artus TM EBV reagent kit with primers that target the EBNA1 protein. Protocol 5 also targeted the EBNA1 gene, while Protocol 4 targeted EBNA-LP. The reportable ranges for these assays also varied with a limit of detection for one assay of 25 copies/ml while another produced quantitative data above 4,000 copies/ml. This information shows the absence of standardization among these sites in terms of the protocols, reagents, and extraction, and amplification systems being used.

CMV

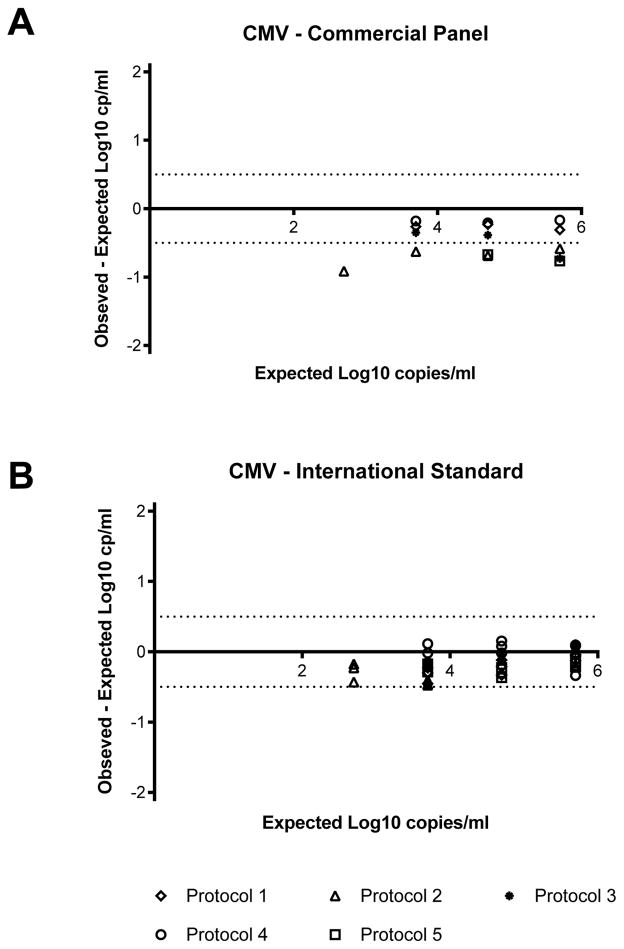

The qualitative and quantitative performance of CMV viral load testing was compared using two different sample panels covering the typical range of concentrations assessed in clinical laboratories using human plasma containing known amounts of CMV or serial dilutions of the WHO International CMV Standard. There were no false positive results reported for the negative control from either panel (Table 2). The results from the commercial panel included a single result using Protocol 5 (see Table 1), in which no viral DNA was detected in the specimen expected to contain 2.7 log10 copies/ml (500 copies/ml) which is below the expected lower limit for Protocol 5. CMV was detected using all five protocols in samples expected to contain greater than 3.7 log10 copies/ml (5000 copies/ml), although one result was not quantifiable. All five protocols provided quantitative results for the commercial panel samples expected to contain 4.7 and 5.7 log10 copies/ml (50,000 and 500,000 copies/ml). The mean viral load measured at each of these concentrations was lower than the expected value. The difference between the mean reported value and the expected value at each concentration varied from 0.44 to 0.54 log10 copies/ml. As shown in Figure 1, individual results for the commercial panel were all below the expected value. Eight of the 20 samples (40%) fell within ±0.5 log10 copies/ml of the expected value, which is considered the acceptable degree of variation for quantitative nucleic acid tests (10). Only two of the five assays gave results within 0.5 log10 of the expected value at every concentration tested. At those concentrations where quantitative results were reported, the difference between the highest viral load result and the lowest viral load result was within or close to 0.5 log10 copies/ml (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Qualitative Performance for CMV Viral Load Testing

| CMV – Commercial panel - Single replicate of each dilution at each site | |||||

| Expected copies/ml (log10 copies/ml) | Negative | Positive* | Quantifiable | Mean (log10 copies/ml) | Range (log10 copies/ml) |

| 0 | 5 | ||||

| 500 (2.7) | 1 | 4 | |||

| 5000 (3.7) | 1 | 4 | 3.34 | 3.07–3.52 | |

| 50,000 (4.7) | 5 | 4.26 | 4.01–4.49 | ||

| 500,000 (5.7) | 5 | 5.19 | 4.94–5.53 | ||

| CMV – WHO International Standard, three replicates of each dilution at each site | |||||

| Expected IU/ml (log10 IU/ml) | Negative | Positive* | Quantifiable | Mean (log10 copies/ml) | Range (log10 copies/ml) |

| 0 | 15 | ||||

| 5 (0.7) | 13 | 2 | |||

| 50 (1.7) | 10 | 5 | |||

| 500 (2.7) | 12 | 3 | 2.42 | 2.27–2.52 | |

| 5000 (3.7) | 1 | 14 | 3.46 | 3.23–3.81 | |

| 50,000 (4.7) | 15 | 4.54 | 4.33–4.85 | ||

| 500,000 (5.7) | 15 | 5.61 | 5.36–5.81 | ||

Positive but below the reportable range

Figure 1. Accuracy of CMV viral loads.

Each point represents an individual replicate from the protocol as indicated in the legend. Negative results and viral load values below the reportable range of the assay for each protocol are not included. The horizontal dotted lines correspond to the acceptable range of variation of ±0.5 log10 copies/ml from 0.

For the CMV WHO International Standard panel, virus was not detected in the majority of samples expected to contain 0.7 or 1.7 log10 copies/ml (5 or 50 copies/ml). CMV was detected in all of the samples expected to contain 2.7 log10 copies/ml (500 copies/ml). Quantitative results were obtained on all but one sample expected to contain 3.7 log10 copies/ml (5000 copies/ml). For those replicates with quantitative data, the mean viral load was lower than the expected value at all concentrations and varied from 0.09 to 0.4 log10 copies/ml. As shown in Figure 1, the majority (39 of 60, 65%) of the individual results were below the expected value and all fell within ±0.5 log10 copies/ml. When data were compared among protocols, the difference between the highest quantitative result and the lowest quantitative result was within or close to the acceptable degree of variation of 0.5 log10 copies/ml (Table 2).

EBV

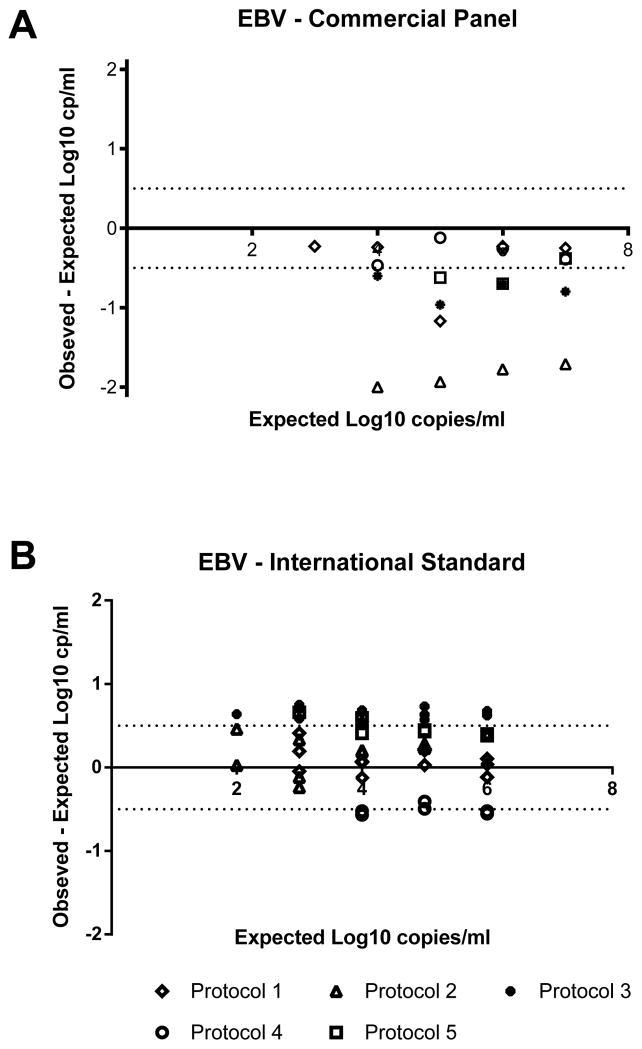

The qualitative and quantitative performance of EBV viral load testing was also performed using the two sample panels: a commercial preparation and the WHO International EBV Standard. As shown in Table 3, there were no false positive results reported on the negative control samples for either panel. There were discrepant results for the samples from the commercial panel expected to contain 3 or 4 log10 copies/ml (1000 or 10,000 copies/ml). At these concentrations, no virus was detected using Protocol 5, while the other protocols were able to detect but not necessarily quantitate virus. Quantitative results were reported from all five protocols for the commercially prepared samples expected to contain at least 5 log10 copies/ml (100,000 copies/ml). The mean EBV viral load on these samples was lower than the expected value at each of the concentrations tested (Table 3). The difference between the mean and the expected value at each concentration ranged between 0.71 and 0.96 log10 copies/ml. The individual results from each protocol were also all less than the expected value, with 8 of the 20 samples falling within 0.5 log10 copies/ml of the expected result (Figure 2). When compared, the difference between the highest result and the lowest result was more than 1.5 log10 copies/ml at every concentration.

Table 3.

Summary of Qualitative Performance for EBV Viral Load Testing

| EBV – Commercial panel - Single replicate of each dilution at each site | |||||

| Number of replicates | |||||

| Expected (log10 copies/ml) | Negative | Positive* | Quantifiable | Mean (log10 copies/ml) | Range (log10 copies/ml) |

| 0 | 5 | ||||

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2.27 | |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 3.17 | 2.00–3.76 | |

| 5 | 5 | 4.04 | 3.07–4.88 | ||

| 6 | 5 | 5.27 | 4.23–5.77 | ||

| 7 | 5 | 6.29 | 5.29–6.75 | ||

| EBV – WHO International Standard, Three replicates of each dilution at each site** | |||||

| Expected IU/ml (log10 IU/ml) | Negative | Positive* | Quantifiable | Mean (log10 copies/ml) | Range (log10 copies/ml) |

| 0 | 14 | ||||

| 10 (1) | 10 | 4 | |||

| 100 (2) | 4 | 7 | 3 | 2.44 | 2.01–3.16 |

| 1000 (3) | 4 | 10 | 3.38 | 2.37–3.75 | |

| 10,000 (4) | 14 | 4.16 | 3.45–4.69 | ||

| 100,000 (5) | 14 | 5.21 | 4.55–5.73 | ||

| 1,000,000 (6) | 14 | 6.18 | 5.46–6.67 | ||

Protocol 4 only 2 replicates;

Positive but below the reportable range

Figure 2. Accuracy of EBV viral loads.

Each point represents an individual replicate from the protocol as indicated in the legend. Negative results and viral load values below the reportable range of the assay for each protocol are not included. The horizontal dotted lines correspond to the acceptable range of variation of ±0.5 log10 copies/ml from 0.

As shown in Table 3, for the WHO International EBV Standard panel, EBV was detected in the majority of the replicates expected to contain 2 log10 copies/ml (100 copies/ml). All of the protocols were able to detect, but not necessarily quantitate, virus in the samples expected to contain 3 log10 copies/ml (1000 copies/ml). For samples expected to contain at least 4 log10 copies/ml (10,000 copies/ml), all five protocols gave quantifiable results. In these cases, the mean viral load was higher than the expected value, with the difference ranging from 0.16 to 0.44 log10 copies/ml. However, when considering data from each laboratory separately, the results were distributed above and below the expected value with the results obtained using protocols 2, 3, 5, and the majority of replicates from protocol 2 above the expected value, and the results from protocol 4 all below the expected value. Of the 42 samples containing at least 4 log10 copies/ml (10,000 copies/ml), 26 (62%) were within 0.5 log10 copies/ml of the expected result. When compared to each other, the difference between the highest result and the lowest result were more than 1.0 log10 copies/ml at each concentration.

Discussion

International guidelines recommend the use of viral load testing for the diagnosis and management of both CMV and EBV infections in organ transplant recipients (1,2,5,17,18). Additionally, these assays provide valuable data for the evaluation of new immunosuppressive regimens or antiviral therapies in clinical trials. The purpose of this study was to compare the current laboratory practices in CMV and EBV viral load testing performed at four large transplantation centers. Similar to previous studies (10,11), we found considerable differences among CMV and EBV viral load values when commercially available viral panels were tested. In all cases, the observed viral load was lower than the expected viral load, suggesting that either the expected concentration of virus in the viral panels was not accurate, or the assays were under calibrated. However, the CMV and EBV viral loads were relatively accurate (±0.5 log10 copies/ml of the expected value) when compared to the WHO Standards. At the time this study was performed, the commercial reagents were not related to any official standard, whereas the assigned value for the concentration of the WHO standards was established in a large multisite study. This may explain why the assays appeared more accurate using WHO standards as the reference material.

Each component of the testing method contributes to observed variation in viral load results, including differences in the extraction method, amplification reagents, genes targeted, and calibrators used (19). In one study comparing EBV viral load results obtained using the same amplification system, viral loads were in close agreement when the same extraction method was used, but varied 2.3 fold when different extraction methods were used (9). Others have shown that automated extraction and commercially available amplification systems tend to perform better than laboratory developed “home brew” assays (10). However, even among commercial systems, considerable differences among viral load values have been reported (8,10). The present data suggest that the assays used for CMV viral load testing provide results within the expected range of variation for this type of assay and thus may be compared from one center to the next. Variation was greater for EBV assays; the basis for this variability is unclear. It is possible that EBV results are more sensitive to differences in extraction methods or in the amplification efficiency for each assay as has been observed by others (9, 11, 12). Laboratory proficiency may also contribute to variability (11). Controversy persists as to which blood compartment should be used to measure EBV viral loads; variability in clinical assays reflects various clinical conditions with differing proportions of encapsulated and free viral DNA. Given the variability in EBV assay data and the variability in levels of EBV associated with clinical disease, for individual patient management it may be most appropriate to use a single EBV assay performed at one laboratory.

The WHO International Standards facilitate the standardization of CMV and EBV viral load testing. These standards will allow the use of multiple clinical laboratories rather than mandating the use of a central or core laboratory in the performance of clinical trials (21). This observation assumes that participating laboratories will demonstrate proficiency in assay performance across the reportable ranges in advance of the trial. In this series, the lower limits of detection or sensitivity of the assays varied between sites. Data do not exist to define a clinically “important” lower limit for reportable viral loads for CMV and EBV. The assays are used in both detection and management of infection and, in practice, viral loads vary widely. While some clinical laboratories use plasma as the clinical specimen of choice and others use whole blood; viral load values cannot be compared across different specimen types given the presence of EBV and CMV DNA in peripheral blood cells that are not present in plasma. Each laboratory will need to convert viral load values from copies to international units. Commercial suppliers will need to recalibrate their assay platforms to the international standards. Laboratories using “home brew” platforms will require experimentation to determine appropriate conversion factors. The availability of viral standards should facilitate clinical trials in the future and also enhance the performance of clinical laboratories for patient care. However, viral load assay standardization must be performed in advance of the initiation of multicenter trials.

Acknowledgments

This research was performed as part of an American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) funded project under Award Number U0163594 (Peter Heeger, PI) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The work was carried out by members of the Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation (CTOT) and Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation in Children (CTOT-C) consortia. These studies were also supported by awards from the NIH/NIAID: U01-AI077816-01 and U01AI063623-04 (JAF), 1U01AI77810-01 (GS, LDI), and U01 AI084150-01 (AM, CL).

Abbreviations

- CTOT

Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- IE

Intermediate Early

- qPCR

Real-Time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Disclosures

JAF of MGH and GS of Washington University were members of the Scientific Advisory Board of PrimeraDx, Inc. Assay systems developed by that company were not used at either site as part of this study. GS is a member of the Roche Diagnostics Advisory Board. All other authors report no potential conflict of interest.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the design and performance of this trial and in writing and in critical revision of the final manuscript. Funding for these studies was secured by JAF (PI, ID mechanistic studies) and PH (PI, mechanistic studies) with LD-I, SCS, and AKM (site PIs).

References

- 1.Andrews PA, Emery VC, Newstead C. Summary of the British Transplantation Society Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of CMV Disease After Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92:1181–7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318235c7fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de la Torre-Cisneros J, Farinas MC, Caston JJ, et al. GESITRA-SEIMC/REIPI recommendations for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in solid-organ transplant patients. Enfermedades infecciosas y microbiologia clinica. 2011;29:735–58. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadaya K, Wunderli W, Deffernez C, et al. Monitoring of cytomegalovirus infection in solid-organ transplant recipients by an ultrasensitive plasma PCR assay. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2003;41:3757–64. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3757-3764.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humar A, Gregson D, Caliendo AM, et al. Clinical utility of quantitative cytomegalovirus viral load determination for predicting cytomegalovirus disease in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1999;68:1305–11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humar A, Snydman D Practice ASTIDCo. Cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9 (Suppl 4):S78–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraft CS, Armstrong WS, Caliendo AM. Interpreting quantitative cytomegalovirus DNA testing: understanding the laboratory perspective. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;54:1793–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Page AK, Jager MM, Kotton CN, Simoons-Smit A, Rawlinson WD. International Survey of Cytomegalovirus Management in Solid Organ Transplantation After the Publication of Consensus Guidelines. Transplantation. 2013 doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31828ee12e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bravo D, Clari MA, Costa E, et al. Comparative evaluation of three automated systems for DNA extraction in conjunction with three commercially available real-time PCR assays for quantitation of plasma Cytomegalovirus DNAemia in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49:2899–904. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00785-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caliendo AM, Ingersoll J, Fox-Canale AM, et al. Evaluation of real-time PCR laboratory-developed tests using analyte-specific reagents for cytomegalovirus quantification. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2007;45:1723–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02558-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang XL, Fox JD, Fenton JM, et al. Interlaboratory comparison of cytomegalovirus viral load assays. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9:258–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preiksaitis JK, Pang XL, Fox JD, et al. Interlaboratory comparison of epstein-barr virus viral load assays. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9:269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayden RT, Hokanson KM, Pounds SB, et al. Multicenter comparison of different real-time PCR assays for quantitative detection of Epstein-Barr virus. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008;46:157–63. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01252-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito Y, Takakura S, Ichiyama S, et al. Multicenter evaluation of prototype real-time PCR assays for Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus DNA in whole blood samples from transplant recipients. Microbiology and immunology. 2010;54:516–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouarin S, Vabret A, Scieux C, et al. Multicentric evaluation of a new commercial cytomegalovirus real-time PCR quantitation assay. Journal of virological methods. 2007;146:147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fryer JF, Heath AB, Anderson R, Minor PD the Collaborative Study Group; Standardization ECoB, editor. Collaborative Study to Evaluate the Proposed 1st WHO International Standard for Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) for Nucleic Acid Amplification (NAT)-Based Assays. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fryer JFHA, Wilkinson DE, Minor PD the collaborative study group. Collaborative study to evaluate the proposed 1st WHO International Standard for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) for nucleic acid amplification (NAT)-based assays. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotton CN. Management of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplantation. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2010;6:711–21. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preiksaitis JK, Brennan DC, Fishman J, Allen U. Canadian society of transplantation consensus workshop on cytomegalovirus management in solid organ transplantation final report. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2005;5:218–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caliendo AM, Shahbazian MD, Schaper C, et al. A commutable cytomegalovirus calibrator is required to improve the agreement of viral load values between laboratories. Clinical chemistry. 2009;55:1701–10. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.124743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]