Abstract

Objective

Examine the relationship between 1- and 2-month weight loss (WL) and 8-year WL among participants enrolled in a lifestyle intervention.

Design & Methods

2290 Look AHEAD participants (BMI: 35.65±5.93kg/m2) with type 2 diabetes received an intensive behavioral WL intervention.

Results

1 and 2-month WL were associated with yearly WL through Year 8 (p’s<0.0001). At Month 1, participants losing 2-4% and >4% had 1.62 (95% CI:1.32,1.98) and 2.79 (95% CI:2.21,3.52) times higher odds of achieving a ≥5% WL at Year 4 and 1.28 (95% CI:1.05,1.58) and 1.77 (95% CI:1.40,2.24) times higher odds of achieving a ≥5% at Year 8, compared to those losing <2% initially. At Month 2, a 3-6% WL resulted in greater odds of achieving a ≥5% WL at Year 4 (OR=1.85; CI:1.48,2.32) and a >6% WL resulted in the greatest odds of achieving a ≥5% WL at Year 4 (OR=3.85; CI:3.05,4.88) and Year 8 (OR=2.28; CI:1.81,2.89), compared to those losing <3%. Differences in adherence between WL categories were observed as early as Month 2.

Conclusions

1 and 2-month WL was associated with 8-year WL. Future studies should examine whether alternative treatment strategies can be employed to improve treatment outcomes among those with low initial WL.

Keywords: weight loss, behavioral treatment, lifestyle intervention, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

There is great variability in both short-term and long-term weight loss (WL) in response to lifestyle interventions (1, 2, 3). For example, among individuals randomized to the lifestyle intervention of the Look AHEAD trial 68% achieved ≥5% WL (a common threshold for clinically meaningful WL) at Year 1 (2) and 50% at Year 8 (4). Thus, although many have success with lifestyle interventions, others do not achieve a clinically meaningful WL. Early identification of non-responders to lifestyle treatment may help improve long-term outcomes.

Weight loss achieved during the first two months of treatment is associated with 12 and 18-month WL (5, 6, 7). For example, Look AHEAD participants with a WL ≥2% at Month 1, or ≥3% at Month 2 had 4.8 and 8.4 times higher odds of achieving a ≥5% WL at Year 1, compared to those losing <2% or <3%, respectively (5). However, whether initial weight change also predicts weight change beyond 18 months is currently unknown. If early WL predicts long-term WL, this could lead to more effective long-term WL programs.

This paper expands upon our previous 1-year findings (5) and examines whether initial WL is also associated with 8-year WL among participants enrolled in a lifestyle intervention. Specifically, we examine the odds of achieving a clinically meaningful (≥5%) WL at Years 4 and 8 based on initial WL at Months 1 and 2. Further, we examine whether adherence differs between those with the greatest and least amount of WL at Month 2.

Methods

Participants

Individuals randomized to the intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI; n=2570) of the Look AHEAD trial were considered in these analyses. Participants had type 2 diabetes, were 45-76 years old, and had a BMI ≥25kg/m2 (or ≥27kg/m2 if taking insulin). Further inclusion/exclusion criteria have been previously reported (8). Study procedures were approved by each study site’s institutional review board, and participants provided written informed consent.

Intervention

The lifestyle intervention has been extensively described elsewhere (4). In short, ILI participants attended weekly treatment meetings during Months 1-6 and 3 meetings per month during Months 7-12. During Years 2-8, the intensity of the intervention was significantly reduced.

Participants in ILI were prescribed a calorie goal of 1200-1800 kcal/day and were instructed to consume <30% of total calories from dietary fat. Meal replacements were provided and participants were instructed to replace two meals and one snack/day with a meal replacement product for Months 1-6, one meal and one snack per day during Months 7-12, and one meal or snack/day in Years 2-8. A home-based physical activity regimen was designed to gradually increase structured activity to ≥175 min/week by Month 6. The intervention had a strong behavioral emphasis.

Outcome measures

Weight was measured weekly at intervention visits and annually at assessment visits. Percent weight change at Months 1 and 2 was calculated using Session 5 and Session 9 weights, respectively. Procedures for dealing with missing weight measurements have been reported previously (5).

Program adherence was measured by: 1) number of intervention meetings attended during weeks 1-9; 2) number of self-reported meal replacements consumed during weeks 2-9; and 3) average self-reported minutes/week of moderate-intensity exercise during weeks 2-9.

Statistical analyses

Participants without Month 1 or 2 weights, at least one follow-up weight, and who underwent bariatric surgery were excluded from all analyses (Figure S1). Logistic regression modeling assessed the relationship between early WL and long-term WL (e.g., Years 4 and 8), defining long-term success as achievement of a ≥5% WL. Bivariate tests of association between 2-month weight category and demographic, diabetes-related, and adherence measures were assessed with two-way ANOVA F-tests for continuous and chi-square for categorical measures (Table S1). Pair-wise differences in adherence measures were examined using the differences of LSMEANS from the aforementioned unadjusted two-way ANOVA. Adjusted logistic regression covariates included clinical site, gender, race, age, and baseline BMI (Table 1). All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Odds of achieving a >5% weight loss at Year 4 or Year 8 based upon change in body weight at Months 1 and 2

| Achieve a ≥5% weight loss at Year 4 |

Achieve a ≥5% weight loss at Year 8 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | |||

| <2% WL | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| 2-4% WL | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.62 (1.32, 1.98) | 1.28 (1.05, 1.58) | |

| Adjusted | 1.68 (1.36, 2.08) | 1.29 (1.04, 1.60) | |

| > 4% WL | |||

| Unadjusted | 2.79 (2.21, 3.52) | 1.77 (1.40, 2.24) | |

| Adjusted | 2.99 (3.34, 3.83) | 1.99 (1.54, 2.55) | |

|

| |||

| 2 months | |||

| < 3% WL | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| 3-6% WL | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.85 (1.48, 2.32) | 1.16 (0.93, 1.45) | |

| Adjusted | 1.96 (1.55, 2.47) | 1.23 (0.97, 1.55) | |

| > 6% WL | |||

| Unadjusted | 3.85 (3.05, 4.88) | 2.28 (1.81, 2.89) | |

| Adjusted | 4.33 (3.36, 5.58) | 2.78 (2.15, 3.57) | |

Odds (95% confidence interval); Adjusted models include age, race/ethnicity, gender, clinic site, and baseline BMI. Note: Secondary analyses testing for differential effects of covariates on longer-term weight loss revealed no significant interactions between gender, race, age, or baseline BMI and early weight loss category (data not shown).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the entire Look AHEAD cohort have been previously reported (8). Participants included in the analyses (n=2290) had a mean±SD baseline BMI of 35.65±5.93kg/m2, 59.17% were female, 63.13% were Caucasian, and the mean age was 58.69±6.82 years. Participants were grouped into 1 of 3 categories designed to be roughly equivalent in size based upon 1-month weight change: WL <2% (mean WL= −0.32±2.75%; n=758); 2-4% (−2.96±0.56%; n=961); or >4% (−5.36±1.80%; n=562), and 2-month weight change: WL <3% (mean WL: −0.93±2.61; n=634); 3-6% (−4.51±0.84; n=916); and >6% (−8.02±1.79; n=714).

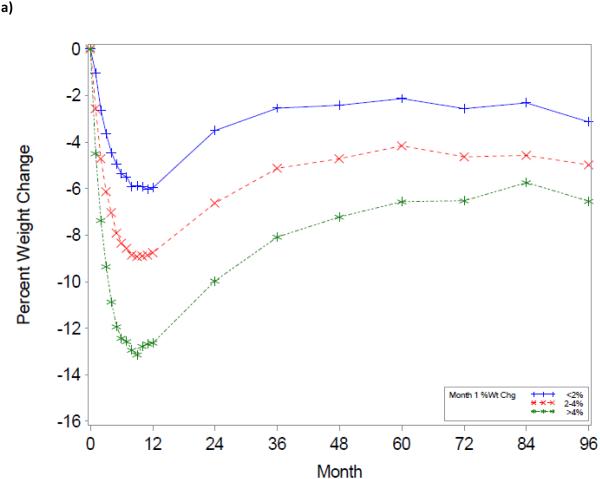

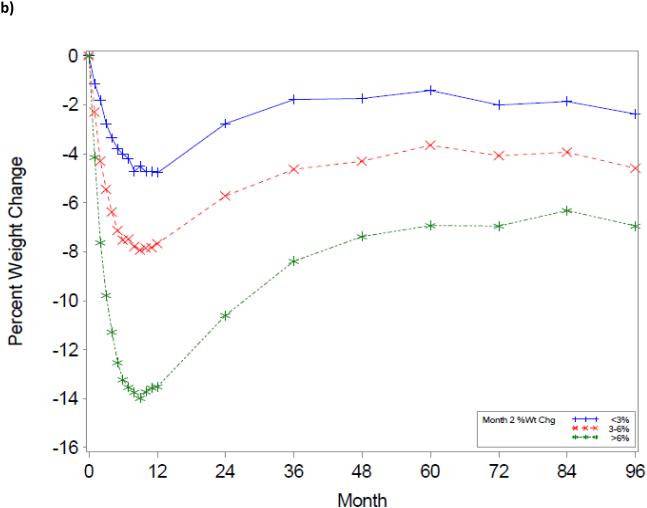

The trajectory of weight change over the 8-year period using the initial WL groupings is shown in Figure 1. As illustrated, a greater WL at Month 1 or 2 was associated with greater WL at any given year over the 8-year period (p’s<0.001).

Figure 1.

Title: Weight change trajectories over an 8-year period, based upon 1-month (a) and 2-month (b) weight change

The odds of achieving a ≥5% WL at Years 4 and 8 were significantly greater among individuals losing the most weight at Months 1 or 2 compared to those losing the least (Table 1). For example, compared to individuals losing <3% at Month 2, those achieving the greatest WL at Month 2 (>6%) had 3.85 (95% CI: 3.05,4.88) and 2.28 (95% CI: 1.81,2.89) higher odds of achieving a ≥5% WL at Years 4 and 8, respectively. Further, individuals losing 3-6% at Month 2 also had higher odds (OR=1.85; 95% CI: 1.48,2.32) of achieving a ≥5% WL at Year 4 but not Year 8 (OR=1.16; 95% CI: 0.93,1.45). Of those who achieved the goal of ≥5% WL at Year 8, 23% had a weight loss <3% at month 2, whereas 36.7% and 40.3% of participants had weight losses of 3-6% or >6% at 2 months, respectively.

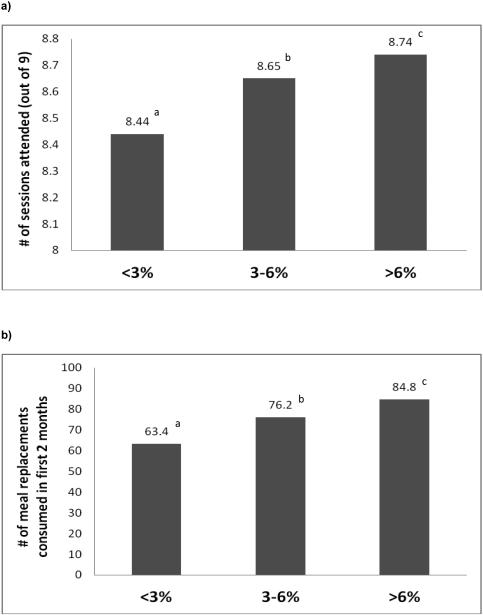

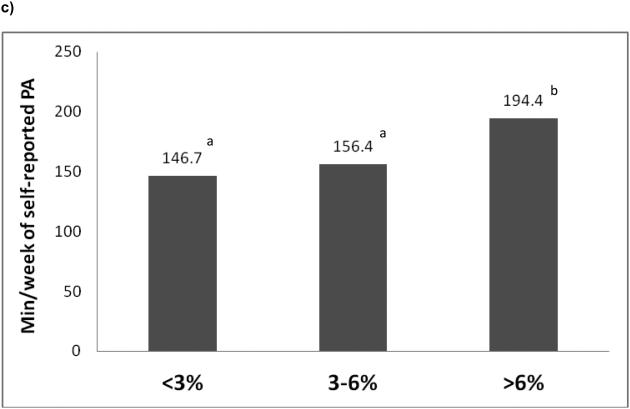

Program adherence was good in all groups, but those losing <3% at Month 2 attended fewer meetings and consumed fewer meal replacements compared to the two groups with higher initial WL (all p<0.0001), and they participated in less physical activity than the highest WL group (p<0.0001; Figure 2). However, adherence at 2 months did not predict 8-year weight change, after controlling for baseline weight and 2-month weight change (p's>0.05). Further, the 2-month initial WL groups differed by gender, ethnicity, education, and insulin usage (p<0.05), but not in diabetes duration, age, initial BMI or waist circumference (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Title: Number of sessions attended (a), meal replacements consumed (b), and weekly minutes of physical activity (c) stratified by initial weight loss category at Month 2.

Legend: PA = physical activity; Values with similar superscripts indicates that groups are similar to one another (p>0.05). Note: Findings presented are from unadjusted models. However the results were unaltered after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, gender, clinical site, and baseline BMI.

Discussion

Weight loss achieved within the first 2 months of a lifestyle intervention was positively associated with WL 8 years later among individuals who were overweight and obese and had type 2 diabetes. This suggests that early WL may be a useful indicator of long-term success. Achievement of a ≥2% WL at Month 1 or ≥6% WL at Month 2 increased the likelihood of achieving a clinically significant WL at Year 8, compared to those losing <2% at Month 1 and <3% at Month 2, respectively. Given that the goal of obesity treatment programs is long-term WL maintenance, the current findings demonstrate the importance participants getting off to a good start in a lifestyle intervention.

Although in general, adherence was excellent during the initial weeks of this study, individuals with poorer WL at Month 2 were already demonstrating poorer adherence at this time compared to those with larger initial WL. While previous reports clearly demonstrate that adherence is strongly associated with WL success(9, 10, 11), the current findings suggest that even at Month 2, lower levels of program adherence could be of concern. Lower levels of adherence and initial WL (i.e., <2% at Month 1 or <3% at Month 2) should be considered red flags for clinicians treating patients with obesity. Future studies should investigate whether providing additional support to these individuals early within a program can improve long-term WL.

With a recent emphasis on cost-effective interventions, an alternative approach would be to discontinue lifestyle treatment in those with low initial WL, as is recommended with newer pharmacotherapy regimens. While there are fewer safety concerns with lifestyle treatment than pharmacotherapy, continued participation in a lifestyle program that is not working may lead to frustration and decreased interest in future weight control efforts. Using initial WL as a criterion for deciding whether to continue a specific treatment may thus be a rational approach in lifestyle, as well as in drug treatments for obesity. If lifestyle treatment is discontinued, alternative treatment approaches could be considered (e.g., different diets, pharmacotherapy, etc.), or these individuals could consider re-attempting lifestyle treatment at a future time point when they are more ready to make the necessary lifestyle changes necessary for successful WL. However, these study findings may only be generalizable to participants with diabetes who receive an intensive lifestyle intervention which utilizes meal replacement products.

This study is the first to demonstrate that WL within the first 2 months of a lifestyle intervention is predictive of long-term WL success (i.e., 8 years later), offering new insight into the potential importance of the initial stages of a lifestyle intervention. Future studies should consider identifying individuals with low initial WL (i.e., <2% at Month 1, or <3% at Month 2) and examine whether it would be beneficial or cost effective to modify (e.g., offer additional support to or recommend alternative treatment options) or discontinue treatment for these individuals.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject?

Post-treatment weight loss predicts long-term weight loss among individuals enrolled in behavioral weight loss programs.

Recent evidence suggests that early weight loss, at 1-2 months, is predictive of 1-year weight loss success.

However, it is unclear whether weight loss within the first few months of treatment also predicts long-term weight loss outcomes, beyond 1 year.

What this study adds

This is the first study to examine the association between initial weight loss (i.e., weight loss within the first 2 months of treatment) and long-term weight loss (through 8 years of follow-up), among individuals enrolled in an intensive lifestyle intervention.

This study demonstrates that initial weight loss is associated with 8-year weight loss, and that poor initial weight loss increases the likelihood of failing to achieve a clinically significant long-term weight loss.

Individuals with poorer weight at Month 2 were already demonstrating poorer adherence at this time point compared to those with larger initial weight loss, demonstrating that early reductions in adherence and low initial weight loss should be considered red flags for clinicians treating patients with obesity.

Acknowledgements

FUNDING AND SUPPORT

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (M01RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346).

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: Federal Express; Health Management Resources; Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan Inc.; Optifast-Novartis Nutrition; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Ross Product Division of Abbott Laboratories; Slim-Fast Foods Company; and Unilever.

ROLE OF SPONSORS: The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases participated in the design and conduct of the study but did not participate in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The decision to publish was made by the Look AHEAD Steering Committee, with no restrictions imposed by the sponsor.

TRIAL PERSONNEL

Look AHEAD research group at Year 8:

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS1; Lee Swartz2; Lawrence Cheskin, MD3; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH3; Kerry Stewart, EdD3; Richard Rubin, PhD3; Jean Arceci, RN; Suzanne Ball; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Danielle Diggins; Mia Johnson; Joyce Lambert; Kathy Michalski, RD; Dawn Jiggetts; Chanchai Sapun

Pennington Biomedical Research Center George A. Bray, MD1; Allison Strate, RN2; Frank L. Greenway, MD3; Donna H. Ryan, MD3; Donald Williamson, PhD3; Timothy Church, MD3 ; Catherine Champagne, PhD, RD; Valerie Myers, PhD; Jennifer Arceneaux, RN; Kristi Rau; Michelle Begnaud, LDN, RD, CDE; Barbara Cerniauskas, LDN, RD, CDE; Crystal Duncan, LPN; Helen Guay, LDN, LPC, RD; Carolyn Johnson, LPN, Lisa Jones; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Cindy Puckett; Marisa Smith; Lauren Cox; Monica Lockett, LPN

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH1; Sheikilya Thomas MPH2; Monika Safford, MD3; Stephen Glasser, MD3; Vicki DiLillo, PhD3; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jane King, MLT; DeLavallade Lee; Andre Morgan; L. Christie Oden; Janet Raines, MS; Cathy Roche, RN, BSN; Jackie Roche; Janet Turman

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital. David M. Nathan, MD1; Enrico Cagliero, MD3; Kathryn Hayward, MD3; Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE2; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD3; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD3; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc, CCS; Mary Larkin, RN; Christine Stevens, RN; Kylee Miller, BA; Jimmy Chen, BA; Karen Blumenthal, BA; Gail Winning, BA; Rita Tsay, RD; Helen Cyr, RD; Maria Pinto

Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD1; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE2; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD3; A. Enrique Caballero, MD3; Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Barbara Fargnoli, MS,RD; Jeanne Spellman, BS, RD; Kari Galuski, RN; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD1; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc3; Ann McNamara, RN; Kristina Spellman, RD

University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus James O. Hill, PhD1; Holly Wyatt, MD3; Marsha Miller, MS RD2; Brent Van Dorsten, PhD3; Judith Regensteiner, PhD3; Debbie Bochert; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS; Loretta Rome, TRS; Terra Thompson, BA; Kirstie Craul, RD, CDE; Sheila Smith, BS; Cecilia Wang, MD

Baylor College of Medicine John P. Foreyt, PhD1; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD2; Molly Gee, MEd, RD2; Henry Pownall, PhD3; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS3; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD3; Peter Jones, MD3; Michele Burrington, RD, RN; Allyson Clark Gardner,MS, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Sarah Lee; Sarah Lane Liscum, RN, MPH; Susan Cantu-Lumbreras; Julieta Palencia, RN; Jennifer Schmidt; Jayne Thomas, RD; Carolyn White

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee East. Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH1; Carolyn Gresham, RN2; Mace Coday, PhD; Lisa Jones, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN; J. Lee Taylor, MEd, MBA

University of Tennessee Downtown. Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD1; Ebenezer Nyenwe, MD3; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN2; Moana Mosby, RN; Amy Brewer, MS, RD,LDN; Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Donna Green, RN; Robert Kores, PhD; Renate Rosenthal, Ph.D.

University of Minnesota Robert W. Jeffery, PhD1; Tricia Skarphol, MA2; John P. Bantle, MD3; J. Bruce Redmon, MD3; Richard S. Crow, MD3; Cindy Bjerk, MS, RD; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Melanie Jaeb, MPH, RD; Philip Lacher, BBA; Patti Laqua, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center, Columbia University Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD1; Jennifer Patricio, MS2; Carmen Pal, MD3; Lynn Allen, MD;Janet Crane, MA, RD, CDN; Lolline Chong, BS, RD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Michelle Horowitz, MS, RD.

University of Pennsylvania Thomas A. Wadden, PhD1; Barbara J Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE 2; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD 3; Gary Foster, PhD 3; Henry Glick, PhD 3; Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH 3; Brooke Bailer, PhD; Yuliis Bell; Chanelle Bishop-Gilyard, Psy.D; Raymond Carvajal, Psy.D; Helen Chomentowski; Renee Davenport; Lucy Faulconbridge, PhD; Louise Hesson, MSN, CRNP; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Sharon Leonard, RD; Caroline Moran, BA; Monica Mullen, RD, MPH; Victoria Webb, BA.; Marion Vetter, MD,RD

University of Pittsburgh John M. Jakicic, PhD1, David E. Kelley, MD1; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE2; Lewis H. Kuller, MD, DrPH3; Andrea Kriska, PhD3; Amy D. Rickman, PhD, RD, LDN3, Lin Ewing, PhD, RN3, Mary Korytkowski, MD3, Daniel Edmundowicz, MD3; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Tammy DeBruce; Barbara Elnyczky; David O. Garcia, MS; Patricia H. Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Susan Harrier, BS; Dianne Heidingsfelder, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Diane Ives, MPH; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Lisa Martich, MS, RD; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Karen Quirin; Joan R. Ritchea; Susan Copelli, BS, CTR

The Miriam Hospital/Alpert Medical School of Brown University Providence, RI Rena R. Wing, PhD1; Caitlin Egan, MS2; Vincent Pera, MD3; Jeanne McCaffery, PhD3; Jessica Unick, PhD3; Ana Almeida; Kirsten Annis, BA; Barbara Bancroft, RN; April Bernier, BS; Sara Cournoyer, BA; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Jose DaCruz; Michelle Fisher, RN, CDOE; Linda Gay, MS, RD, CDE; Stephen Godbout, BS, BSN; Jacki Hecht, RN, MSN; Marie Kearns, MA; Deborah Maier-Fredey, MS, RD; Heather Niemeier, PhD; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Angela Marinilli-Pinto, PhD; Deborah Ranslow-Robles; Hollie Raynor, PhD; Erica Robichaud, MSW, RD; Jane Tavares, BA; Kristen Whitehead

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Steven M. Haffner, MD1; Helen P. Hazuda, PhD1; Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE2; Carlos Lorenzo, MD3; Charles F. Coleman, MS, RD; Domingo Granado, RN; Kathy Hathaway, MS, RD; Juan Carlos Isaac, RC, BSN; Nora Ramirez, RN, BSN; Ronda Saenz, MS, RD

VA Puget Sound Health Care System / University of Washington Steven E. Kahn MB, ChB1; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE2; Robert Knopp, MD3; Edward Lipkin, MD, PhD3; Dace Trence, MD3; Elaine Tsai, MD3; Valerie Baldisserotto, RD; Linda Castine, RN, BSN, CDE; Basma Fattaleh, BA; Kathy Fitzpatrick, RN; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Sukwan Nhan Jolley, RD; Hailey Mack, RD, MS, CDE; Ivy Morgan-Taggart; Anne Murillo, BS; Gretchen Otto, BS; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; Jolanta Socha, BS; April Thomas, MPH, RD; Alan Wesley, BA; Diane Wheeler, RD, CDE

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH1; Paula Bolin, RN, MC2; Tina Killean, BS2; Cathy Manus, LPN3; Jonathan Krakoff, MD3; Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH3; Sara Michaels, MD3; Paul Bloomquist, MD3; Bernadita Fallis RN, RHIT, CCS; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Christina Morris, BA; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Miranda Smart; Janelia Smiley; Teddy Thomas, BS; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC

University of Southern California Anne Peters, MD1; Siran Ghazarian, MD2

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University Mark A. Espeland, PhD1; Judy L. Bahnson, BA, CCRP3; Lynne E. Wagenknecht, DrPH3; David Reboussin, PhD3; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD3; Alain G. Bertoni, MD, MPH3; Wei Lang, PhD3; Michael S. Lawlor, PhD3; David Lefkowitz, MD3; Gary D. Miller, PhD3; Patrick S. Reynolds, MD3; Paul M. Ribisl, PhD3; Mara Vitolins, DrPH3; Daniel Beavers, PhD3; Haiying Chen, PhD, MM3; Delia S. West, PhD3; Lawrence M. Friedman, MD3; Ron Prineas, MD3; Tandaw Samdarshi, MD3; Kathy M. Dotson, BA2; Amelia Hodges, BS, CCRP2; Dominique Limprevil-Divers, MA, MEd2; Karen Wall2; Carrie C. Williams, MA, CCRP2; Andrea Anderson, MS; Jerry M. Barnes, MA; Mary Barr; Tara D. Beckner; Cralen Davis, MS; Thania Del Valle-Fagan, MD; Melanie Franks, BBA; Candace Goode; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; Mary A. Hontz, BA; Sarah A. Gaussoin, MS; Don G. Hire, BS; Patricia Hogan, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca H. Neiberg, MS; Julia T. Rushing, MS; Valery Effoe Sammah; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Terri Windham

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco Michael Nevitt, PhD1; Ann Schwartz, PhD2; John Shepherd, PhD3; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA; Susan Ewing, MS; Cynthia Hayashi; Jason Maeda, MPH

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD1; Jessica Chmielewski2; Vinod Gaur, PhD4

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Elsayed Z. Soliman MD, MSc, MS1; Charles Campbell 2; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD3; Mary Barr; Susan Hensley; Julie Hu; Lisa Keasler; Yabing Li, MD

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities Elizabeth J Mayer-Davis, PhD1; Robert Moran, PhD1

Hall-Foushee Communications, Inc.

Richard Foushee, PhD; Nancy J. Hall, MA

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Mary Evans, PhD; Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD, PhD; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Peter Kaufman, PhD, FABMR

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Edward W. Gregg, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00017953

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Cheskin is the Chair of the Scientific Advisory Board for Medifast, Inc. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Wadden TA, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Clark JM, Delahanty LM, Hill JO, et al. Four-Year Weight Losses in the Look AHEAD Study: Factors Associated With Long-Term Success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Ryan DH, Johnson KC, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1550–1559. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. discussion 1559-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: the look AHEAD study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:5–13. doi: 10.1002/oby.20662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unick JL, Hogan PE, Neiberg RH, Cheskin LJ, Dutton GR, Evans-Hudnall G, et al. Evaluation of early weight loss thresholds for identifying nonresponders to an intensive lifestyle intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:1608–1616. doi: 10.1002/oby.20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elfhag K, Rossner S. Initial weight loss is the best predictor for success in obesity treatment and sociodemographic liabilities increase risk for drop-out. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nackers LM, Ross KM, Perri MG. The association between rate of initial weight loss and long-term success in obesity treatment: does slow and steady win the race? Int J Behav Med. 2010;17:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Bright R, Clark JM, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elfhag K, Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Edelstein SL, Hill JO, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12:1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unick JL, Jakicic JM, Marcus BH. Contribution of Behavior Intervention Components to 24-Month Weight Loss. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181bd1a57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.