Abstract

Fibrocytes are fibroblast-like cells, which appear to participate in wound healing and are present in pathological lesions associated with asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, and scleroderma. Fibrocytes differentiate from CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes, and the presence of serum delays this process dramatically. We previously purified the factor in serum, which inhibits fibrocyte differentiation, and identified it as serum amyloid P (SAP). As SAP binds to Fc receptors for immunoglobulin G (IgG; FcγRs), FcγR activation may be an inhibitory signal for fibrocyte differentiation. FcγR are activated by aggregated IgG, and we find aggregated but not monomeric, human IgG inhibits human fibrocyte differentiation. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to FcγRI (CD64) or FcγRII (CD32) also inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. Aggregated IgG lacking Fc domains or aggregated IgA, IgE, or IgM do not inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. Incubation of monocytes with SAP or aggregated IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation. Using inhibitors of protein kinase enzymes, we show that Syk- and Src-related tyrosine kinases participate in the inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation. These observations suggest that fibrocyte differentiation can occur in situations where SAP and aggregated IgG levels are low, such as the resolution phase of inflammation.

Keywords: monocytes, inflammation, cellular differentiation, serum amyloid P, FcγR

INTRODUCTION

Tissue damage or the presence of pathogens leads to the recruitment and activation of peripheral blood monocytes [1, 2]. These cells differentiate into tissue macrophages and are a key component of the innate immune response essential for the control of many infections. After the removal of pathogenic organisms, macrophages remove apoptotic cells and promote tissue regeneration by stimulating fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM) production [3, 4].

The source of the fibroblasts responsible for the repair of wound lesions or the hyperplasia characteristic of chronic inflammation is still controversial. The conventional hypothesis is that local quiescent fibroblasts migrate into the affected area, produce ECM proteins, and promote wound contraction [5]. An alternative hypothesis is that circulating fibroblast-like cell precursors (fibrocyte precursors), present within the blood, migrate to sites of injury, where they differentiate into fibroblast-like cells—fibrocytes—and mediate tissue repair [6–9]. Fibrocytes express markers of hematopoietic (CD45, major histocompatibility complex class II, CD34) and stromal cells (collagen I and III and fibronectin) [10, 11]. Fibrocytes, at sites of tissue injury, secrete inflammatory cytokines and ECM proteins and promote angiogenesis and wound contraction [6, 12]. Fibrocytes are also associated with the formation of fibrotic lesions after infection or inflammation and are implicated in fibrosis associated with autoimmune diseases [11, 13–17].

Fibrocyte precursors originate from ~10% of circulating CD14-positive/CD16-negative peripheral blood monocytes [6, 18, 19] (data not shown). At least two factors promote the differentiation of monocytes into fibrocytes. First, direct contact between CD14+ monocytes and T cells increases the number of fibrocytes [6]. Second, transforming growth factor-β acts as a maturation factor for fibrocytes once differentiation has occurred [6, 19].

We have found that the differentiation of fibrocytes from monocytes is inhibited by serum amyloid P (SAP), which overrides the positive effect of T cells [18]. In the absence of serum or purified SAP, monocytes differentiate into fibrocytes within 3 days. SAP, a member of the pentraxin family of proteins, which includes C-reactive protein (CRP), is produced by the liver, secreted into the blood, and circulates in the blood as stable pentamers [20–23]. SAP appears to play a role in the initiation and resolution phases of the immune response [24–26]. SAP binds to sugar residues on the surface of bacteria, leading to their opsonization and engulfment [23, 24]. SAP also binds to free DNA and chromatin generated by apoptotic cells at the resolution of an immune response, thus preventing a secondary inflammatory response [25–27].

Receptors for the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (IgG; FcγRs) are found on the surface of a variety of hematopoietic cells. There are four distinct classes of FcγR. FcγRI (CD64) is the high-affinity receptor for IgG expressed by peripheral blood monocytes and binds monomeric IgG with a high affinity [28, 29]. FcγRII (CD32) and FcγRIII (CD16) are low-affinity receptors for IgG and only bind aggregated IgG efficiently. FcγRII is expressed by peripheral blood B cells and monocytes, whereas FcγRIII is expressed by natural killer cells and a subpopulation of monocytes [30–32]. Recently, a new FcγR has been identified in mice [33]. FcγRIV is present on murine peripheral blood monocytes and neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells and binds murine IgG2a and IgG2b antibodies efficiently. There is a putative, human FcγRIV gene, but the biological functions of the protein, such as ligand specificity and cellular expression, are as yet unknown [34].

Bacteria and proteins bound by SAP are removed by phagocytic cells, such as macrophages, as a result of the ability of SAP to bind to all three classical FcγRs, with a preference for FcγRI and FcγRII [35, 36]. CRP appears to bind with a high affinity to FcγRII and a lower affinity to FcγRI but does not bind FcγRIII [37– 41]. SAP and CRP initiate intracellular signaling events consistent with FcγR ligation [35, 38, 41, 42].

FcγR activation and induction of intracellular signaling pathways are dependent on the cross-linking of multiple receptors by aggregated IgG [29, 43]. The intracellular regions of FcγRI and FcγRIII lack activation motifs and signal through the associated FcRγ chain, which contains tyrosine residues in immunoreceptor tyrosine activation motifs (ITAMs), phosphorylated following cross-linking and leading to the downstream signaling cascade. FcγRII has an ITAM domain within the cytoplasmic tail and can initiate the signaling cascade independently of the FcRγ [43, 44].

As SAP inhibits fibrocyte differentiation and binds to FcγR and as IgG binds to FcγR, we determined whether IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation [18, 35]. We find that aggregated but not monomeric IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation and that FcγRI and FcγRII are involved. These observations suggest that monocytes will differentiate into fibrocytes in situations where SAP and aggregated IgG levels are low.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies, proteins, and inhibitors

Human IgA, IgG, IgM, and IgG F(ab′)2 fragments were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgG, goat F(ab′)2 anti-murine IgG, goat F(ab′)2 anti-rabbit IgG, and whole mouse IgG1, whole mouse IgG2a, and mouse F(ab′)2 IgG1 isotype control antibodies were from Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc. (Birmingham, AL). Sheep red blood cells (SRBC) and rabbit anti-SRBC were from ICN (Irvine, CA). Purified human SAP and human IgE were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). F(ab′)2 fragments of the blocking monoclonal antibodies (mAb) to FcγRI (Clone 10.1, IgG1 isotype) and FcγRII (Clone 7.3, IgG1 isotype) were from Ancell (Bayport, MN) [29, 45–47]. The following primary mAb were used for immunohistochemistry: anti-CD14 [Clone M5E2, IgG2a, BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA)], anti-CD34 [Clone QBend10, IgG1, GeneTex (San Antonio, TX)], CD43 (Clone 1G10, IgG1, BD Biosciences), pan-CD45 (clone H130, IgG1, BD Biosciences), anti-prolyl 4-hydrolase [Clone 5B5, IgG1, Dako (Carpinteria, CA)], and anti-α smooth muscle actin [α-SMA; Clone 1A4, IgG2a, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO)]. Collagen-I was detected using an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). 4-Amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl) pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP2; AG 1879), 4-amino-7-phenylpyrazol[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP3), and the Syk inhibitor 3-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-ylmethylene)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indole-5-sulfonamide were from Calbiochem.

Cell culture and fibrocyte differentiation assay

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from buffy coats (Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center, Houston, TX) by Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) as described previously [18]. Cells were incubated in serum-free medium (SFM), which consists of RPMI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 1× ITS-3 [500 µg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10 µg/ml insulin, 5 µg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml sodium selenite, 5 µg/ml linoleic acid, and 5 µg/ml oleic acid; Sigma-Aldrich]. Normal human serum (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at the stated concentrations. PBMC were cultured in flat-bottomed, 96-well, tissue-culture plates (Type 353072, BD Biosciences Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA) in 200 µl vol at 2.5 × 105 cells per ml in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for the indicated times. Fibrocytes were identified by morphology in viable cultures as adherent cells with an elongated, spindle-shaped morphology as distinct from lymphocytes or adherent monocytes. Enumeration of fibrocytes was performed on cells cultured for 5 days. Cells were air-dried, fixed in methanol, and stained with eosin and methylene blue (Hema 3 stain, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Fibrocytes from duplicate wells were counted in five different 900 µm-diameter fields per well, using the above criteria of an elongated spindle shape and the presence of an oval nucleus. All cultures were counted by at least two independent observers. We observed 1.2 ± 0.6 × 104 (mean±sd, n=12 healthy individuals) fibrocytes per ml peripheral blood, with a range of 3.7 × 103–2.9 × 104 fibrocytes per ml. These results are similar to previous data and indicate that fibrocyte precursors account for ~1% of the total PBMC [6, 17–19].

Immunohistochemistry

PMBC were cultured on eight-well glass microscope slides (Lab-Tek, Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) in serum-free medium for 5 days. Cells were air-dried for at least 60 min before fixation in acetone for 15 min. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched for 15 min with 0.3% H2O2 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation in 4% BSA in PBS for 60 min. Slides were incubated with 5 µg/ml primary antibodies in PBS containing 4% BSA for 60 min. Isotype-matched, irrelevant antibodies were used as controls. Slides were then washed in three changes of PBS over 15 min and incubated for 30 min with 2.5 µg/ml biotinylated goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG or biotinylated goat F(ab′)2 anti-rabbit IgG (cross-adsorbed against human Ig, Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc.). After washing, the biotinylated antibodies were detected by ExtrAvidin peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining was developed with diaminobenzadine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 min and counterstained for 10 s with Gill’s hematoxylin #3 (Sigma-Aldrich). All procedures were at room temperature.

FcγR ligation

Heat-aggregated Igs were prepared by diluting whole IgA, IgE, IgG, IgM, or IgG F(ab′)2 fragments to 2 mg/ml in 0.9% saline and then heating to 65°C for 60 min. Large protein precipitates were then removed by centrifugation at 1000 g for 2 min. Isolation of monomeric IgG and clarification of SAP preparations were performed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Monomeric IgG was cross-linked by the addition of 500 ng/ml goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgG for 30 min at 4°C. Opsonized SRBC were prepared by incubating a 1% suspension of SRBC in RPMI 1640 with the highest concentration of nonagglutinating polyclonal rabbit anti-SRBC (generally 1/2000). SRBC were then washed three times in RPMI and added to PBMC at a range of ratios from 1:1 to 50:1, SRBC:monocyte. Monocytes were enumerated by morphology using a hemocytometer. To cross-link individual FcγR, PBMC were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with 1 µg/ml F(ab′)2 anti-FcγR (10.1) or F(ab′)2 anti-FcγRII (7.3), and receptors were then cross-linked by the addition of 500 ng/ml F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG for 30 min at 4°C. PBMC were then warmed to 37°C and cultured for 5 days. To block individual FcγR, PBMC were cultured for 60 min at 4°C with 1 µg/ml F(ab′)2 anti-FcγRI (10.1) or F(ab′)2 anti-FcγRII (7.3) mAb. SAP at 0.5 µg/ml was then added, and the PBMC were cultured for 5 days. Inhibition of Src-related tyrosine kinases (SRTK) and Syk was achieved by incubating PBMC at 4°C with 10 nM PP2, PP3, or the Syk inhibitor for the indicated times. PBMC were then washed twice in ice-cold, serum-free medium and then cultured with anti-FcγRI or anti-FcγRII mAb, SAP, or aggregated IgG as indicated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences between two groups were assessed by Student’s t-test. Differences among multiple groups were assessed by ANOVA using Bonferroni’s post-test. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Monomeric IgG has little effect on fibrocyte differentiation

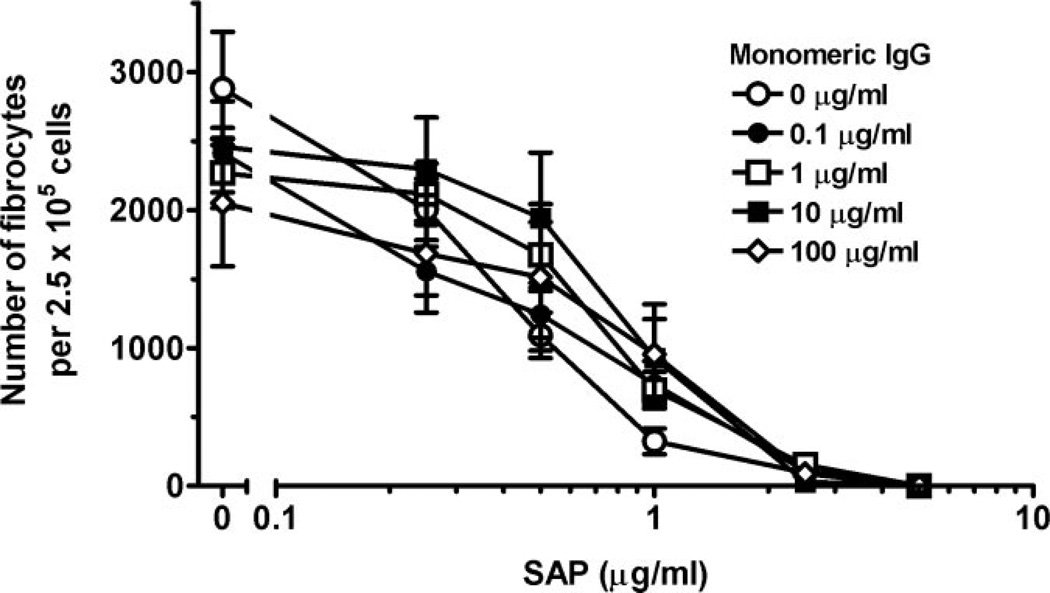

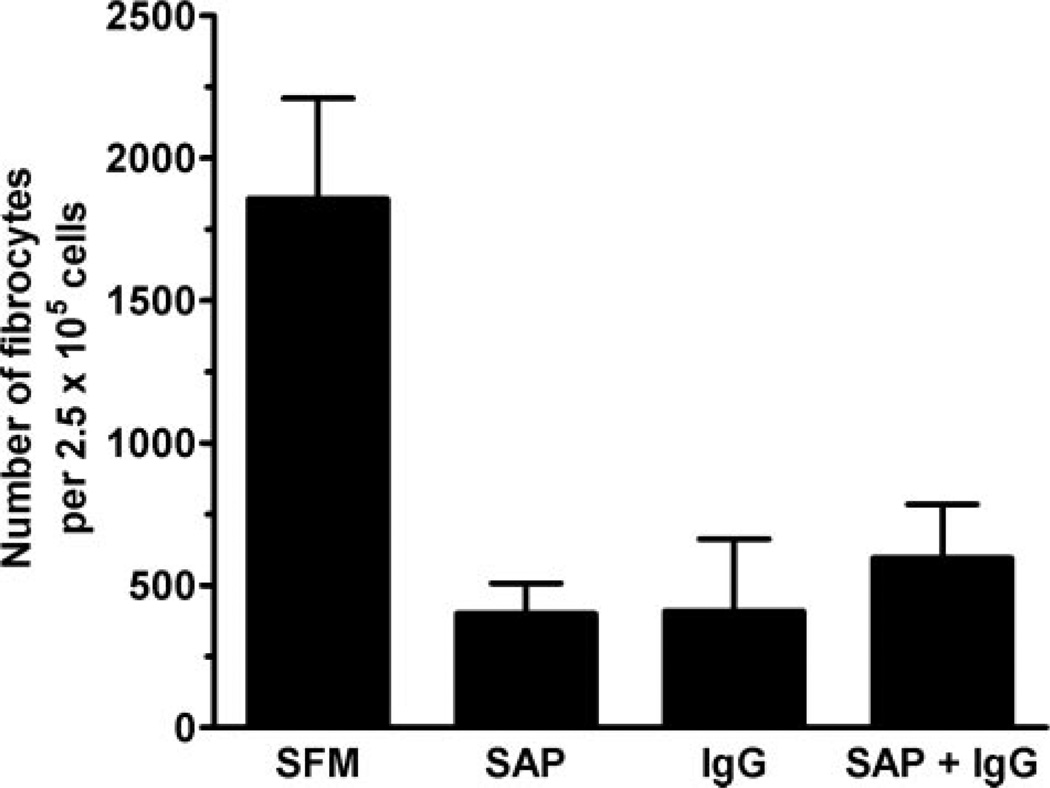

SAP binds to cells via FcγR, with a higher affinity for FcγRI compared with FcγRII and FcγRIII [35, 36]. Monocytes constitutively express FcγRI, and as this receptor binds monomeric IgG, it is saturated in vivo [28, 31]. To determine whether the presence of monomeric, human IgG could affect fibrocyte differentiation or prevent SAP from inhibiting fibrocyte differentiation, human PBMC were cultured in serum-free medium in the presence of different concentrations of monomeric, human IgG for 30 min. We cultured PBMC in a serum-free medium system to reduce any unwanted interactions between the FcγR and possible ligands present in serum, such as IgG, CRP, or SAP, which at the concentrations indicated, was then added, and the cells were cultured for 5 days. As we reported previously, 1 µg/ml SAP in the absence of IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.001; Fig. 1) [18]. The addition of monomeric, human IgG in a dose range from 0.25 to 100 µg/ml, which corresponds to 0.0025–1% serum, respectively, had no significant effect on the inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP (P=0.44). In the absence of SAP, monomeric IgG had no statistically significant effect on the differentiation of monocytes to fibrocytes (P=0.54). To ensure that the commercial preparations of SAP were not aggregated and thus providing a multimeric rather than a pentameric FcγR-binding protein, SAP was clarified by centrifugation at 100,000 g. PBMC were then incubated in serum-free medium with clarified or the standard preparation of SAP at 1 µg/ml. There was no difference in the ability of the two preparations to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation, suggesting that the SAP was not aggregated (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Monomeric human IgG does not prevent the inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP. PBMC at 2.5 × 105 per ml were cultured in serum-free medium for 5 days with the indicated concentrations of SAP and human, monomeric IgG. Cells were then air-dried, fixed, and stained, and fibrocytes were enumerated by morphology. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=4 separate donors). When this assay was repeated using PBMC from other donors, similar results were obtained with the exception that the number of fibrocytes in serum-free medium varied from 1500 to 4000 per 2.5 × 105 cells, depending on the donors.

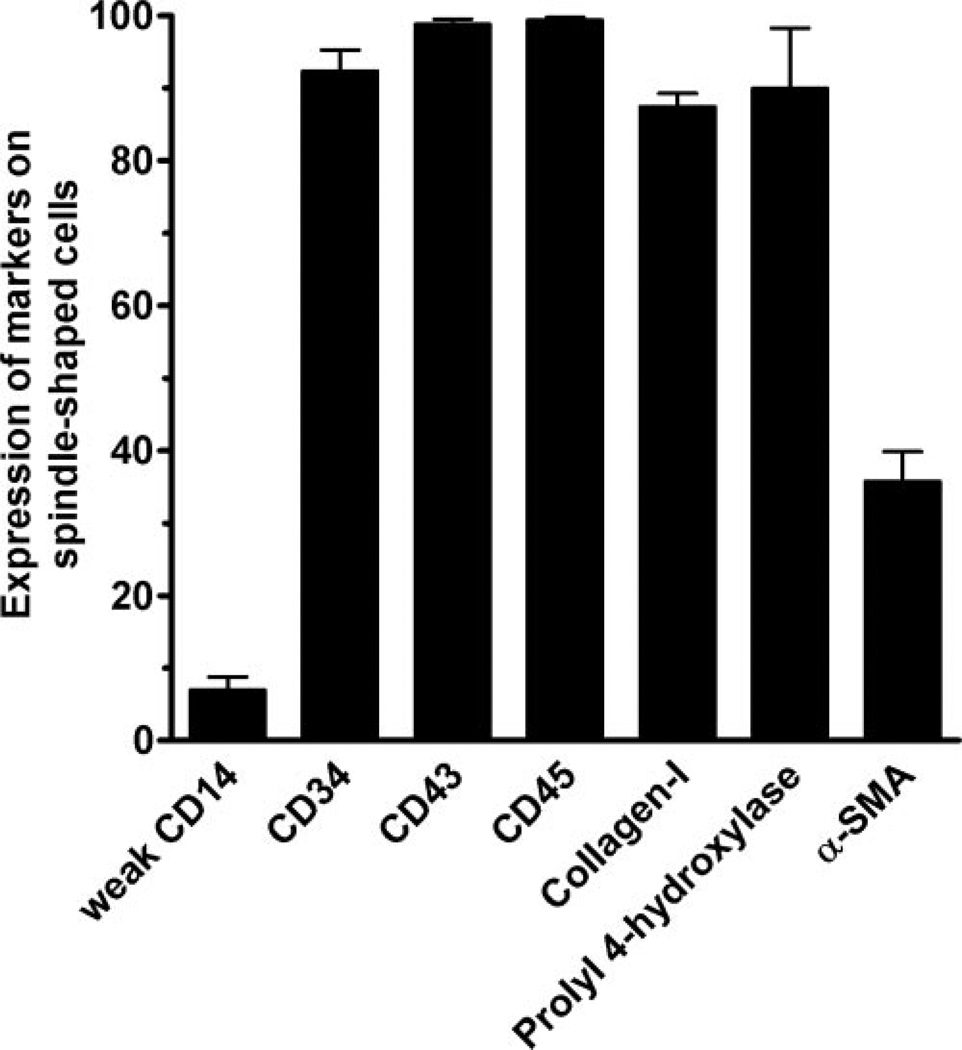

To confirm that the spindle-shaped cells we identified as fibrocytes are indeed fibrocytes, we stained the cells for known fibrocyte markers including CD14, CD34, CD43, CD45, collagen-I, and prolyl 4-hydrolylase (a key enzyme in the production of collagen), as well as α-SMA, a marker of activated fibrocytes [6, 10, 18]. Greater than 90% of the fibrocytes expressed CD34, CD43, CD45, collagen-I, and prolyl 4-hydroxylase, and approximately one-third of them expressed α-SMA (Fig. 2). A small number of the fibrocytes expressed low levels of CD14, which probably reflects their recent differentiation from CD14-positive monocytes (Fig. 2) [6, 18].

Fig. 2.

Expression of molecules by fibrocytes. PBMC at 2.5 × 105 cells per ml were cultured in eight-well glass slides in serum-free medium for 5 days. Cells were then air-dried, fixed in acetone, and stained with antibodies. Positive staining was identified by brown staining with a blue hematoxylin counterstain. At least 100 elongated cells with oval nuclei were examined from at least 10 randomly selected fields, and the percentage of positive cells is expressed as the mean ± sem (n=3–5 separate donors).

Cross-linked IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation

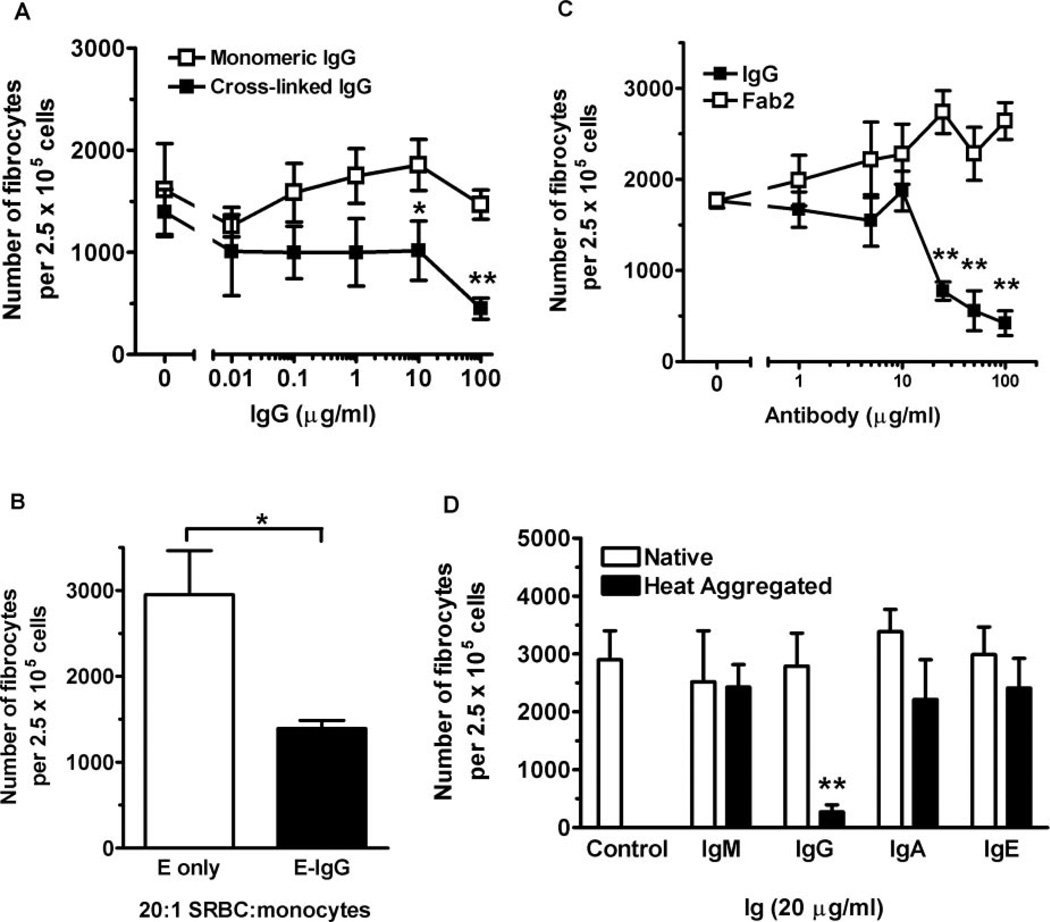

SAP is a pentameric protein with five potential FcγR-binding sites per molecule, which may cross-link FcγR effectively without additional proteins [18, 35]. To test whether IgG, when cross-linked, could also inhibit fibrocyte differentiation, we incubated PBMC for 60 min at 4°C in serum-free medium with increasing concentrations of monomeric, human IgG. The cells were then washed to remove unbound IgG. Goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgG was then added as the cross-linking agent, and PBMC were cultured for 5 days. In the absence of human IgG, the goat F(ab′)2 had no significant effect on fibrocyte differentiation. The addition of 500 ng/ml goat anti-human IgG to concentrations of monomeric IgG at 10 µg/ml and above caused a significant inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 3A). In the absence of a cross-linking agent, monomeric IgG had no effect on fibrocyte differentiation (Figs. 1 and 3A). As the initial reagent in these experiments was monomeric, human IgG, which will only bind efficiently to FcγRI, these data suggest that cross-linking FcγRI on monocytes may be a mechanism that inhibits the differentiation of fibrocytes [28].

Fig. 3.

Cross-linked but not monomeric IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation. (A) PBMC were incubated with the indicated concentrations of monomeric, human IgG for 60 min. PBMC were then washed and incubated in the presence or absence of 500 ng/ml goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgG. PBMC were then cultured at 2.5 × 105 per ml in serum-free medium for 5 days. PBMC were then air-dried, fixed, and stained, and fibrocytes were enumerated by morphology. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of a number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=4 separate donors). Compared with monomeric IgG, cross-linked, human IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly at 10 and 100 µg/ml (P=0.03 and P=0.003, respectively), as determined by a Student’s t-test. (B) PBMC at 2.5 × 105 per ml were cultured in serum-free medium for 5 days with SRBC or SRBC labeled with a 1/2000 dilution of rabbit IgG anti-SRBC at a ratio of 20:1, SRBC:monocytes. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=3 separate donors). Compared with SRBC (E only), SRBC opsonized with rabbit anti-SRBC (E-IgG) inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P=0.018), as determined by a Student’s t-test. (C) PBMC were cultured as above in the presence of the indicated concentrations of heat-aggregated, human IgG or heat-aggregated, human F(ab′)2. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=3 separate donors). Compared with heat-aggregated F(ab′)2, heat-aggregated, whole IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly at concentrations of 25 µg/ml and higher, as determined by a Student’s t-test. (D) PBMC were cultured as above in the presence of 20 µg/ml native or heat-aggregated, human IgA, IgE, IgG, or IgM. Only PBMC cultured in heat-aggregated IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.01), as determined by ANOVA (n=3 separate donors). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To determine whether other IgG immune complexes could influence monocyte-to-fibrocyte differentiation, we examined the effect of particulate, opsonized SRBC complexes. PBMC were cultured for 5 days in serum-free medium with rabbit IgG bound (opsonized) to SRBC at a ratio of 20:1, SRBC:monocytes. The presence of SRBC, opsonized with rabbit anti-SRBC antibody (E-IgG), inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly, compared with PBMC cultured with nonopsonized SRBC (E only; Fig. 3B). Aggregated rabbit IgG binds efficiently to human FcγRI and FcγRII, so these data suggest that ligation of FcγRI and FcγRII is an inhibitory signal for fibrocyte differentiation [28, 48]. Together, these data suggest that cross-linked IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation.

Cross-linked IgG requires its Fc region to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation

IgG binds to FcγR via the Fc portion of IgG. To test the hypothesis that cross-linked IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation by ligating FcγR, we determined whether cross-linked F(ab′)2 IgG, which has no Fc region, could inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. We found that heat-aggregated, whole, human IgG but not heat-aggregated F(ab′)2 was a potent inhibitor of fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that heat-aggregated IgG also inhibits fibrocyte differentiation and that the Fc region of IgG is necessary for this effect.

Only IgG immune complexes inhibit fibrocyte differentiation

Monocytes express IgA receptors, low numbers of IgE receptors, and the recently characterized IgM receptor [49–51]. To determine if other Igs inhibit fibrocyte differentiation, we added native or heat-aggregated IgA, IgE, IgG, or IgM to PBMC. Only heat-aggregated IgG but not monomeric IgG or monomeric or heat-aggregated IgA, IgE, or IgM could inhibit fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 3D). These data together suggest that ligation and cross-linking of FcγRs are inhibitory signals for monocyte-to-fibrocyte differentiation but that ligation of the other Ig receptors has no effect of fibrocyte differentiation.

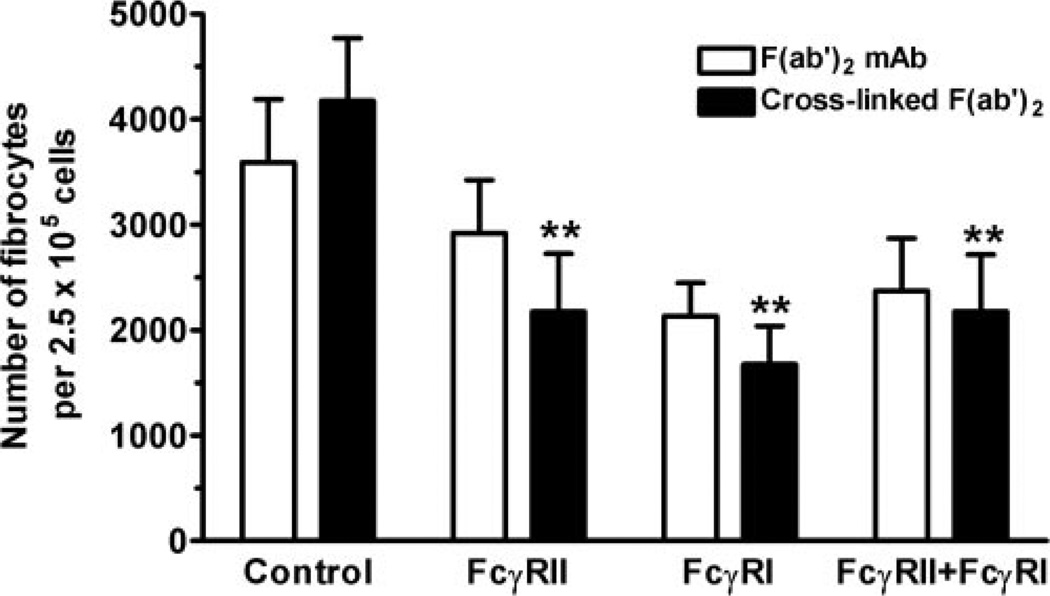

Ligation of FcγRI (CD64) or FcγRII (CD32) inhibits fibrocyte differentiation

To determine if cross-linked IgG activates FcγR to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation, PBMC were cultured for 5 days in serum-free medium in the presence or absence of free or cross-linked F(ab′)2 antibodies to FcγRI or FcγRII. Cross-linking FcγRI or FcγRII alone inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (Fig. 4). However, there was no additional inhibition when both receptors were cross-linked together, suggesting that no synergistic interaction occurs. These experiments show that we could inhibit fibrocyte differentiation to ~50% by the addition of 1 µg/ml mAb. Greater inhibition could be achieved by incubating PBMC with higher concentrations of mAb (5 and 10 µg/ml); however, these concentrations of mAb also led to significant cell death (data not shown). Although not statistically significant, as determined by ANOVA, there was also a trend that bivalent F(ab′)2 mAb, especially anti-FcγRI, were able to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 4). If these data are analyzed by Student’s t-test comparing PBMC cultured with F(ab′)2 FcγRI mAb with PBMC cultured with control mAb, then the data are significantly different (P=0.043). These results suggest that ligation and cross-linking of FcγRI or FcγRII can inhibit fibrocyte differentiation.

Fig. 4.

FcγRI and FcγRII cross-linking inhibits fibrocyte differentiation. PBMC at 2.5 × 105 per ml were cultured in serum-free medium for 5 days in the presence or absence of 1 µg/ml of the indicated murine F(ab′)2 anti-FcγR or control IgG1 antibodies, in the presence or absence of 500 ng/ml goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG. Cells were then air-dried, fixed, and stained, and fibrocytes were enumerated by morphology. Compared with PBMC cultured in the presence of 500 ng/ml goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgG, cells cultured in the presence of the FcγRI or FcγRII mAb inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.01), as determined by ANOVA (n=3 separate donors). *, P < 0.01.

In an attempt to determine if SAP inhibits fibrocyte differentiation preferentially through FcγRI or FcγRII pathways, we preincubated PBMC with F(ab′)2-blocking mAb to FcγRI or FcγRII before the addition of an intermediate concentration of SAP (0.5 µg/ml). As expected, the addition of SAP inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly by ~60% (P<0.001, comparing control to SAP-treated PBMC; data not shown). Preincubation of PBMC with blocking mAb to FcγRI, FcγRII, or FcγRI combined with FcγRII had no effect (data not shown). As discussed above, even the presence of bivalent F(ab′)2 mAb to FcγRI or FcγRII inhibits fibrocyte differentiation when compared with an IgG1 F(ab′)2 control mAb (Fig. 4). Therefore, using this technique, we were unable to determine which FcγR is ligated preferentially by SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation.

To determine if SAP and aggregated IgG have an additive effect with respect to inhibiting fibrocyte differentiation, we cultured PBMC in the presence or absence of 1 µg/ml SAP and 20 µg/ml aggregated IgG. As expected, SAP and IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly when added individually to PBMC as determined by ANOVA (P<0.001), but there was no additive or synergistic interaction when these molecules were used together (P>0.05; Fig. 5). This apparent lack of synergy may be because SAP binds aggregated IgG, and this may have partially reduced the ability of the SAP or IgG to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation [52].

Fig. 5.

SAP and aggregated IgG have no additive or synergistic effects on fibrocyte differentiation. PBMC at 2.5 × 105 cells per ml were cultured in serum-free medium for 5 days in the presence or absence of 1 µg/ml SAP, 20 µg/ml heat-aggregated IgG, or SAP and heat-aggregated IgG together. Cells were then air-dried, fixed, and stained, and fibrocytes were enumerated by morphology. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of a number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells. Compared with PBMC, cultured in the presence of SAP or IgG individually, cells cultured in the presence of SAP and IgG had no significant difference in fibrocyte differentiation, as determined by ANOVA (n=3 separate donors).

Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation is Syk- and Src kinase-dependent

FcγR activation leads to a cascade of signaling events initiated by two main kinases. The initial events following FcγR aggregation involve the phosphorylation of intracellular ITAMs present on the cytoplasmic tail of FcγRII or the FcRγ chain associated with FcγRI by SRTK [43]. In monocytes, the main Src kinases associated with FcγRI and FcγRII are hck and lyn [53–56]. The phosphorylated ITAMs then recruit cytoplasmic Src homology 2-containing kinases, especially Syk, to the ITAMs, and Syk then activates a series of downstream signaling molecules [43, 57].

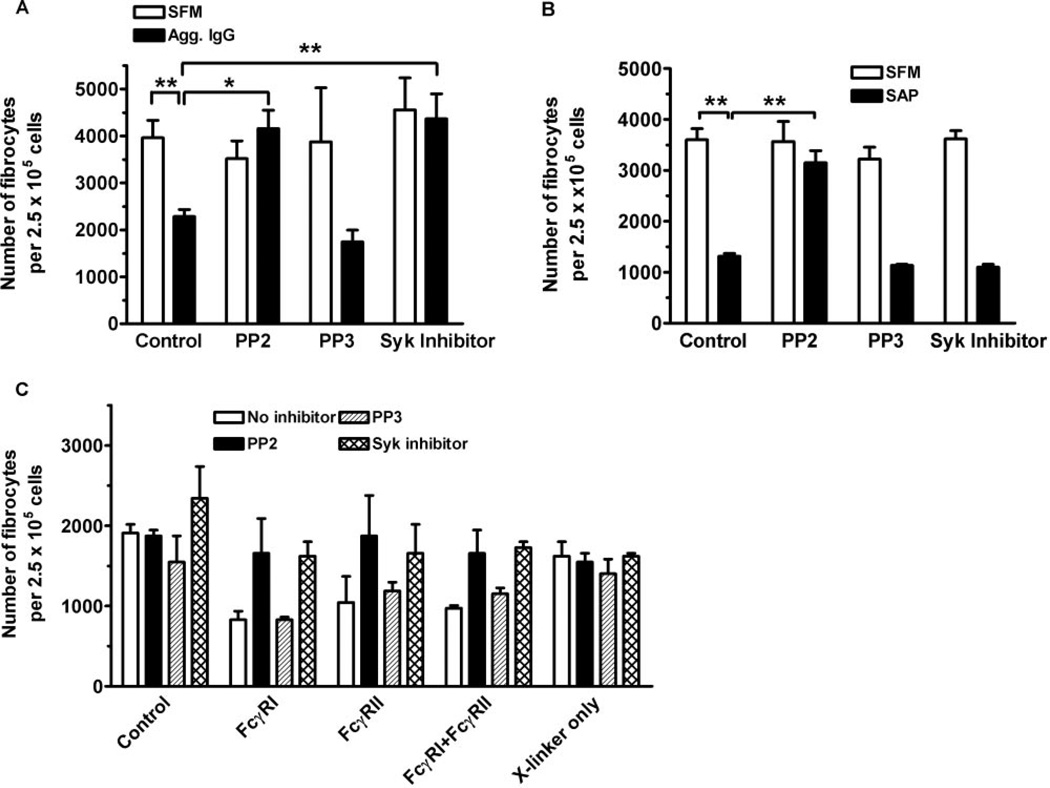

To determine the roles of SRTK and Syk in the regulation of fibrocyte differentiation, we preincubated PBMC with the specific SRTK inhibitor PP2 or the specific Syk inhibitor 3-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl-methylene)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indole-5-sulfonamide before the addition of SAP or aggregated IgG [58, 59]. We used this Syk inhibitor instead of the standard Syk inhibitor piceatannol, as piceatannol, at concentrations used to inhibit Syk in whole cells (10 µM), also inhibits a variety of other enzymes and transcription factors. These proteins include the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKA), PKC, myosin light-chain kinase, tumor necrosis factor-induced nuclear factor-B activation, and interferon α-mediated signaling via signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins [60–63]. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by aggregated IgG was abolished by PP2 and the Syk inhibitor (Fig. 6A). Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP was SRTK-dependent, as PP2 but not the control compound PP3 abolished the ability of SAP to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. However, the Syk inhibitor was unable to inhibit the effect of SAP (Fig. 6B). Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by activating FcγRI or FcγRII alone or both receptors together was dependent on SRTK and Syk, as the inhibition was lost when PBMC were preincubated with PP2 or the Syk inhibitor (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that aggregated IgG inhibits fibrocyte differentiation through a pathway involving Syk and SRTK and that SAP appears to signal through a SRTK-dependent but Syk-independent pathway.

Fig. 6.

Effect of SRTK and Syk inhibitors on fibrocyte differentiation. (A) PBMC were incubated for 60 min at 4°C with 10 nM PP2, PP3, or Syk inhibitor. PBMC were then washed twice and cultured in the presence or absence of heat-aggregated, human IgG for 60 min at 4°C. PBMC were then washed twice and cultured at 2.5 × 105 per ml for 5 days in serum-free medium. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=3 separate donors). Compared with PBMC cultured in SFM, aggregated IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.01). Compared with PBMC cultured with 10 µg/ml aggregated IgG, PBMC preincubated with PP2 (P<0.05) or the Syk inhibitor (P<0.01) significantly inhibited the ability of IgG to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation as determined by ANOVA. (B) PBMC at 2.5 × 105 per ml were incubated for 60 min at 4°C with 10 nM PP2, PP3, or Syk inhibitor. PBMC were then washed twice and cultured for 5 days in the presence or absence of 0.5 µg/ml SAP. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=3 separate donors). Compared with PBMC cultured in SFM, SAP inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.01), as determined by ANOVA. Compared with PBMC cultured in 0.5 µg/ml SAP, preincubation with PP2 significantly inhibited the ability of SAP to prevent fibrocyte differentiation (P<0.01), as determined by ANOVA. (C) PBMC were incubated for 60 min at 4°C with 10 nM PP2, PP3, or Syk inhibitor. PBMC at 2.5 × 105 per ml were then cultured in serum-free medium for 5 days in the presence or absence of 1 µg/ml of the indicated murine F(ab′)2 anti-FcγR antibodies in the presence or absence of 500 ng/ml goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG. Compared with control cultures, PBMC cultured with anti-FcγRI, anti-FcγRII, or both antibodies inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.05), as determined by ANOVA. Results are expressed as the mean ± sd of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (one of two separate donors). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

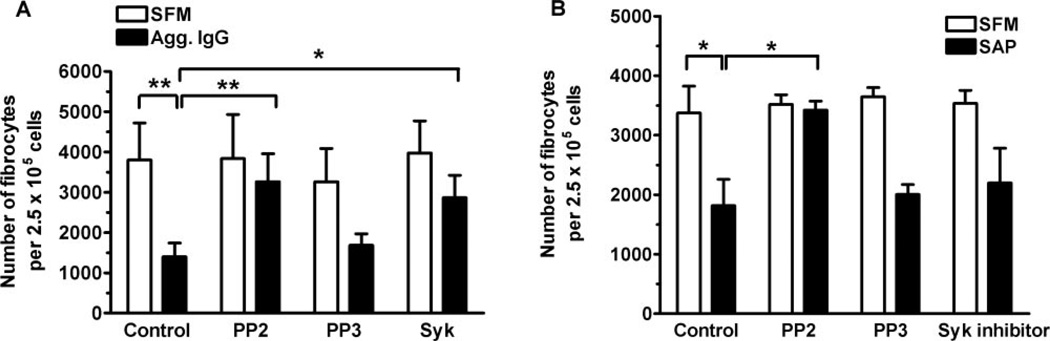

Ligation of FcγR on monocytes inhibits fibrocyte differentiation

To determine whether the inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by FcγR ligation is specific to monocytes, we stimulated monocytes in the absence of other cell types. PBMC were allowed to adhere to the tissue-culture plates for 60 min, and the nonadherent cells were then removed. This routinely produces a population of cells, which is more than 98% monocytes [64–66]. The monocytes were then incubated on ice for 60 min in the presence or absence of the SRTK inhibitor PP2, the control compound PP3, or the Syk inhibitor. Cells were then washed twice before the addition of aggregated IgG or SAP for 60 min at 4°C. Monocytes were then washed twice, and the nonadherent lymphocytes were added back, as fibrocyte differentiation is a T cell-dependent process [6]. As observed with whole PBMC, aggregated IgG was able to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation when added to monocytes specifically (Fig. 7A). The SRTK inhibitor PP2 and the Syk inhibitor abolished the ability of aggregated IgG to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 7A). Monocytes incubated with SAP for 1 h also led to the inhibition of differentiation into fibrocytes (Fig. 7B). As observed with whole PBMC cultures, inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP was SRTK-dependent but Syk-independent (Figs. 6B and 7B). These data suggest that a 1-h exposure to agents, which activate FcγR in a SRTK- and Syk-dependent manner, will inhibit monocyte-to-fibrocyte differentiation.

Fig. 7.

Direct ligation of FcγR on monocytes leads to the inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation. PBMC at 2.5 × 105 per ml were incubated for 60 min at 37°C, and nonadherent cells were then removed by pipetting. (A) The adherent monocytes were incubated for 60 min at 4°C in the presence or absence of 10 nM PP2, PP3, or Syk inhibitor. Monocytes were then washed twice and cultured in the presence or absence of heat-aggregated, human IgG for 60 min at 4°C. Monocytes were then washed twice, and the nonadherent cells were replaced to a final concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml and then cultured for 5 days at 37°C in serum-free medium. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=3 separate donors). Compared with monocytes cultured in SFM, aggregated IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.01), as determined by ANOVA. Compared with monocytes incubated with 10 µg/ml aggregated IgG, preincubation with PP2 (P<0.01) or the Syk inhibitor (P<0.05) significantly inhibited the ability of IgG to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation as determined by ANOVA. (B) Adherent monocytes were incubated for 60 min at 4°C in the presence or absence of 10 nM PP2, PP3, or Syk inhibitor. Monocytes were then washed and incubated for 60 min at 4°C in the presence or absence of 0.5 µg/ml SAP. Cells were then washed, the nonadherent cells were replaced, and the cells were cultured for 5 days. Compared with monocytes cultured in SFM, SAP inhibited fibrocyte differentiation significantly (P<0.05), as determined by ANOVA. Compared with monocytes cultured in 0.5 µg/ml SAP, preincubation with PP2 significantly inhibited the ability of SAP to prevent fibrocyte differentiation (P<0.05), as determined by ANOVA. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem of the number of fibrocytes per 2.5 × 105 cells (n=3 separate donors). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

We found that cross-linked or heat-aggregated IgG inhibits the initial differentiation of fibrocytes. This inhibition is dependent on the Fc portion of IgG, as F(ab′)2 fragments of IgG could not inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. Monomeric IgG and monomeric or cross-linked IgA, IgE, or IgM were also incapable of inhibiting fibrocyte differentiation.

The mechanisms by which SAP and aggregated IgG inhibit fibrocyte differentiation appear to be distinct but related. The inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP was dependent on SRTK, as this inhibition was PP2-sensitive. By comparison, aggregated IgG inhibited fibrocyte differentiation by a SRTK-and Syk-dependent process. These data suggest that SAP and IgG activate one or more SRTK, but the subsequent events are divergent. Alternatively, the differences observed could be explained if SAP preferentially binds FcγRII, as FcγRII signaling is more resistant to Syk antagonists [55, 67, 68].

Recently, it has been shown that binding of CRP, the protein highly related to SAP, to FcγRI cannot inhibit IgG binding [41]. This suggests that pentraxins may bind to FcγR and especially FcγRI outside the IgG-binding site. The binding of pentraxins outside the IgG-binding sites could explain our observation that monomeric IgG does not prevent SAP from inhibiting fibrocyte differentiation. Therefore, reagents that block IgG binding to FcγR may not be useful for assessing the effects of SAP on FcγR and may also explain some of the controversy regarding the specificity of SAP and CRP for FcγR [39–41, 69, 70]. Manolov et al. [70] showed that although CRP does bind directly to FcγRII, the use of anti-CRP antibodies enhanced CRP binding to FcγRII and led to false positives. Therefore, antipentraxin antibodies or anti-FcγR antibodies may not be suitable reagents for investigating the interaction of pentraxins with FcγR.

The observations that bivalent F(ab′)2 mAb to FcγRI and FcγRII have some ability to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation suggest that cross-linking pairs of FcγR is sufficient to inhibit fibrocyte differentiation. It would have been preferable to add monovalent Fab anti-FcγRI or anti-FcγRII mAb as reagents, as they would not bind more than one FcγR, but these reagents were unavailable to us. Also, it would have been helpful to compare the effect of F(ab′)2 mAb to the activating FcγRIIa or inhibitory FcγRIIb receptors found on monocytes, but these antibodies were not available to us.

During an initial immune response, IgG molecules bound to pathogens form an immune complex that activates FcγR [28, 44]. Our data suggest that these complexes would inhibit the differentiation of monocytes into fibrocytes. However, during the resolution phase, IgG and many other serum proteins such as SAP are cleared from the site of infection by four main mechanisms: restoration of hemostasis following repair of blood vessels, drainage of the wound fluid through the lymphatic system, engulfment by phagocytic cells, and degradation by proteases [71–74]. Assuming that SAP and immune complexes are cleared from the tissue during the resolution phase, the resulting low levels of SAP and immune complexes would create an environment favorable for the differentiation of fibrocytes and thus aid tissue regeneration and wound healing [4, 75].

Immune complexes are also found in chronic inflammatory conditions. In rheumatoid arthritis, immune complexes are present mainly in the synovial fluid and on the superficial layers of the joint [76, 77]. Immune complexes are absent frequently from the interior of the tissue (pannus) invading the cartilage [78, 79]. The leading edge of the invading pannus is populated mainly by macrophages, whereas the cells in the main body are more fibroblast-like [79]. Given our observation that immune complexes inhibit fibrocyte differentiation, a possible explanation for this distribution of cells in the pannus is that the presence of immune complexes at the leading edge of the pannus would block fibrocyte differentiation. As these cells at the leading edge internalize and clear the immune complexes, the deeper layers of cells would have lower levels of these complexes. These lower levels may facilitate monocyte-to-fibrocyte differentiation. In vitro, we were unable to detect IgG or SAP after culturing PBMC for 3 days in serum-free medium, suggesting that any residual IgG or SAP present on the surface of the cells ex vivo was catabolized, removing ligands that might inhibit fibrocyte differentiation (data not shown).

Fibrocytes have a major role in burns, wound healing, and infection, and fibrocytes have been associated with fibrosis in asthma, scleroderma, infection, and malignancy [6, 8, 9, 11, 15, 17–19, 80, 81]. In addition, the survival and retention of leukocytes at sites of chronic inflammation are regulated by fibroblast-like cells, and an interesting possibility is that some of these fibroblast-like cells are fibrocytes [75, 82–86]. Previously, we have shown that SAP can regulate fibrocyte differentiation and that circulating levels of SAP may be a factor in fibrotic disease such as scleroderma [18]. We have now shown that aggregated IgG (which is present at sites of inflammation) and SAP inhibit the differentiation of fibrocyte precursors, possibly by cross-linking FcγRI and FcγRII. Mechanisms, which could regulate FcγR ligation, might allow useful therapies for the treatment of inflammation and wounds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Grant Number C-1555 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation and Grant 005/04 from the Scleroderma Foundation. We thank Dr. John Kanellis for helpful comments; Hillary Patuwo, Diane Shao, and Sanna Ronkainen for enumeration of fibrocytes; and Jeff Crawford for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon S. Development and distribution of mononuclear phagocytes: relevance to inflammation. In: Gallin JI, Synderman R, editors. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins; 1999. pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orteu CH, Poulter LW, Rustin MHA, Sabin CA, Salmon M, Akbar AN. The role of apoptosis in the resolution of T cell-mediated cutaneous inflammation. J. Immunol. 1998;161:1619–1629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenhalgh DG. The role of apoptosis in wound healing. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998;30:1019–1030. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark RA. Fibrin and wound healing. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;936:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J. Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majno G. Chronic inflammation: links with angiogenesis and wound healing. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;153:1035–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65648-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metz CN. Fibrocytes: a unique cell population implicated in wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60:1342–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori L, Bellini A, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. Fibrocytes contribute to the myofibroblast population in wounded skin and originate from the bone marrow. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;304:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol. Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesney J, Metz C, Stavitsky AB, Bacher M, Bucala R. Regulated production of type I collagen and inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood fibrocytes. J. Immunol. 1998;160:419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartlapp I, Abe R, Saeed RW, Peng T, Voelter W, Bucala R, Metz CN. Fibrocytes induce an angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 2001;15:2215–2224. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0049com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesney J, Bacher M, Bender A, Bucala R. The peripheral blood fibrocyte is a potent antigen-presenting cell capable of priming naive T cells in situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6307–6312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowper SE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: the first 6 years. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2003;15:785–790. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200311000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesney J, Bucala R. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: mesenchymal precursor cells and the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2000;2:501–505. doi: 10.1007/s11926-000-0027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:438–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, Mori L, Mattoli S. Identification of circulating fibrocytes as precursors of bronchial myofibroblasts in asthma. J. Immunol. 2003;171:380–389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Gomer RH. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5537–5546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, Scott PG, Giuffre J, Shankowsky HA, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. Peripheral blood fibrocytes from burn patients: identification and quantification of fibrocytes in adherent cells cultured from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Lab. Invest. 2002;82:1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000027841.50269.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steel DM, Whitehead AS. The major acute phase reactants: C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P component and serum amyloid A protein. Immunol. Today. 1994;15:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gewurz H, Zhang XH, Lint TF. Structure and function of the pentraxins. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1995;7:54–64. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchinson WL, Hohenester E, Pepys MB. Human serum amyloid P component is a single uncomplexed pentamer in whole serum. Mol. Med. 2000;6:482–493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepys MB, Booth DR, Hutchinson WL, Gallimore JR, Collins PM, Hohenester E. Amyloid P component. A critical review. Amyloid. 1997;4:274–295. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noursadeghi M, Bickerstaff MC, Gallimore JR, Herbert J, Cohen J, Pepys MB. Role of serum amyloid P component in bacterial infection: protection of the host or protection of the pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:14584–14589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bickerstaff MC, Botto M, Hutchinson WL, Herbert J, Tennent GA, Bybee A, Mitchell DA, Cook HT, Butler PJ, Walport MJ, Pepys MB. Serum amyloid P component controls chromatin degradation and prevents antinuclear autoimmunity. Nat. Med. 1999;5:694–697. doi: 10.1038/9544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bijl M, Horst G, Bijzet J, Bootsma H, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Serum amyloid P component binds to late apoptotic cells and mediates their uptake by monocyte-derived macrophages. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:248–254. doi: 10.1002/art.10737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du Clos TW. C-reactive protein reacts with the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein. J. Immunol. 1989;143:2553–2559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravetch JV, Kinet JP. Fc receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1991;9:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hulett MD, Hogarth PM. Molecular basis of Fc receptor function. Adv. Immunol. 1994;57:1–127. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60671-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daeron M. Structural bases of Fc γ R functions. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1997;16:1–27. doi: 10.3109/08830189709045701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grage-Griebenow E, Flad HD, Ernst M. Heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001;69:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Heterogeneity of human blood monocytes: the CD14+CD16+ subpopulation. Immunol. Today. 1996;17:424–428. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. FcγRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity. 2005;23:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis RS, Dennis G, Jr, Odom MR, Gibson AW, Kimberly RP, Burrows PD, Cooper MD. Fc receptor homologs: newest members of a remarkably diverse Fc receptor gene family. Immunol. Rev. 2002;190:123–136. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.19009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bharadwaj D, Mold C, Markham E, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component binds to Fc γ receptors and opsonizes particles for phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 2001;166:6735–6741. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mold C, Gresham HD, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein mediate phagocytosis through murine Fc γ Rs. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1200–1205. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marnell LL, Mold C, Volzer MA, Burlingame RW, Du Clos TW. C-reactive protein binds to Fc γ RI in transfected COS cells. J. Immunol. 1995;155:2185–2193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bharadwaj D, Stein MP, Volzer M, Mold C, Du Clos TW. The major receptor for C-reactive protein on leukocytes is Fcγ receptor II. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:585–590. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Clos TW, Mold C, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Response: human C-reactive protein does not bind to FcγRIIa on phagocytic cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:642. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodman-Smith KB, Gregory RE, Harrison PT, Raynes JG. FcγRIIa expression with FcγRI results in C-reactive protein- and IgG-mediated phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;75:1029–1035. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodman-Smith KB, Melendez AJ, Campbell I, Harrison PT, Allen JM, Raynes JG. C-reactive protein-mediated phagocytosis and phospholipase D signaling through the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin G (FcγRI) Immunology. 2002;107:252–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi M, Tridandapani S, Zhong W, Coggeshall KM, Mortensen RF. C-reactive protein induces signaling through Fc γ RIIa on HL-60 granulocytes. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1413–1418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daeron M. Fc receptor biology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:203–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dougherty GJ, Selvendran Y, Murdoch S, Palmer DG, Hogg N. The human mononuclear phagocyte high-affinity Fc receptor, FcRI, defined by a monoclonal antibody, 10.1. Eur. J. Immunol. 1987;17:1453–1459. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlossman SF, Boumsell L, Gilks W, Harlan JM, Kishimoto T, Ritz J, Shaw S, Silverstein RL, Springer TA, Tedder TF, Todd RF. Leukocyte Typing V: White Cell Differentiation Antigens. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison PT, Allen JM. High affinity IgG binding by FcγRI (CD64) is modulated by two distinct IgSF domains and the transmembrane domain of the receptor. Protein Eng. 1998;11:225–232. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfefferkorn LC, van de Winkel JG, Swink SL. A novel role for IgG-Fc. Transductional potentiation for human high-affinity Fc γ receptor (Fc γ RI) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:8164–8171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.8164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monteiro RC, van de Winkel JGJ. IgA Fc receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:177–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gould HJ, Sutton BJ, Beavil AJ, Beavil RL, McCloskey N, Coker HA, Fear D, Smurthwaite L. The biology of IgE and the basis of allergic disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:579–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shibuya A, Sakamoto N, Shimizu Y, Shibuya K, Osawa M, Hiroyama T, Eyre HJ, Sutherland GR, Endo Y, Fujita T, Miyabayashi T, Sakano S, Tsuji T, Nakayama E, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Nakauchi H. Fc α/μ receptor mediates endocytosis of IgM-coated microbes. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:441–446. doi: 10.1038/80886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown MR, Anderson BE. Receptor-ligand interactions between serum amyloid P component and model soluble immune complexes. J. Immunol. 1993;151:2087–2095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duchemin AM, Anderson CL. Association of non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases with the Fc γ RI/γ-chain complex in monocytic cells. J. Immunol. 1997;158:865–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghazizadeh S, Bolen JB, Fleit HB. Physical and functional association of Src-related protein tyrosine kinases with Fc γ RII in monocytic THP-1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:8878–8884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang ZY, Hunter S, Kim MK, Chien P, Worth RG, Indik ZK, Schreiber AD. The monocyte Fcγ receptors FcgγRI/γ and FcγRIIA differ in their interaction with Syk and with Src-related tyrosine kinases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:491–499. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korade-Mirnics Z, Corey SJ. Src kinase-mediated signaling in leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000;68:603–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turner M, Schweighoffer E, Colucci F, Di Santo JP, Tybulewicz VL. Tyrosine kinase SYK: essential functions for immunoreceptor signaling. Immunol. Today. 2000;21:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01574-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bain J, McLauchlan H, Elliott M, Cohen P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem. J. 2003;371:199–204. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lai JYQ, Cox PJ, Patel R, Sadiq S, Aldous DJ, Thurairatnam S, Smith K, Wheeler D, Jagpal S, Parveen S. Potent small molecule inhibitors of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:3111–3114. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sada K, Takano T, Yanagi S, Yamamura H. Structure and function of Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2001;130:177–186. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ashikawa K, Majumdar S, Banerjee S, Bharti AC, Shishodia S, Aggarwal BB. Piceatannol inhibits TNF-induced NF-B activation and NF-B-mediated gene expression through suppression of IBγ kinase and p65 phosphorylation. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6490–6497. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Su L, David M. Distinct mechanisms of STAT phosphorylation via the interferon-α/β receptor. Selective inhibition of STAT3 and STAT5 by piceatannol. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12661–12666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng J, Ramirez VD. Piceatannol, a stilbene phytochemical, inhibits mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase activity by targeting the F1 complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;261:499–503. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akbar AN, Salmon M, Ivory K, Taki S, Pilling D, Janossy G. Human CD4+ CD45RO+ and CD4+ CD45RA+ T cells synergize in response to alloantigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991;21:2517–2522. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salmon M, Pilling D, Borthwick NJ, Viner N, Janossy G, Bacon PA, Akbar AN. The progressive differentiation of primed T cells is associated with an increasing susceptibility to apoptosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:892–899. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pilling D, Akbar AN, Bacon PA, Salmon M. CD4+ CD45RA+ T cells from adults respond to recall antigens after CD28 ligation. Int. Immunol. 1996;8:1737–1742. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim MK, Pan XQ, Huang ZY, Hunter S, Hwang PH, Indik ZK, Schreiber AD. Fc γ receptors differ in their structural requirements for interaction with the tyrosine kinase Syk in the initial steps of signaling for phagocytosis. Clin. Immunol. 2001;98:125–132. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hunter S, Sato N, Kim MK, Huang ZY, Chu DH, Park JG, Schreiber AD. Structural requirements of Syk kinase for Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Exp. Hematol. 1999;27:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saeland E, van Royen A, Hendriksen K, Vile-Weekhout H, Rijkers GT, Sanders LAM, van de Winkel JGJ. Human C-reactive protein does not bind to FcγRIIa on phagocytic cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:641–642. doi: 10.1172/JCI12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Manolov DE, Rocker C, Hombach V, Nienhaus GU, Torzewski J. Ultrasensitive confocal fluorescence microscopy of C-reactive protein interacting with FcγRIIa. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:2372–2377. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147407.17137.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cochrane CG, Weigle WO, Dixon FJ. The role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the initiation and cessation of the Arthus vasculitis. J. Exp. Med. 1959;110:481–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.110.3.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waller M. IgG hydrolysis in abscesses. I. A study of the IgG in human abscess fluid. Immunology. 1974;26:725–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haslett C, Henson PM. Resolution of inflammation. In: Clark RAF, Henson PM, editors. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. New York, NY: Plenum; 1988. pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shearer JD, Coulter CF, Engeland WC, Roth RA, Caldwell MD. Insulin is degraded extracellularly in wounds by insulin-degrading enzyme (EC 3.4.24.56) Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:E657–E664. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.4.E657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buckley CD, Pilling D, Lord JM, Akbar AN, Scheel-Toellner D, Salmon M. Fibroblasts regulate the switch from acute resolving to chronic persistent inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01863-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. 1996;85:307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cooke TD, Hurd ER, Jasin HE, Bienenstock J, Ziff M. Identification of immunoglobulins and complement in rheumatoid articular collagenous tissues. Arthritis Rheum. 1975;18:541–551. doi: 10.1002/art.1780180603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shiozawa S, Jasin HE, Ziff M. Absence of immunoglobulins in rheumatoid cartilage-pannus junctions. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:816–821. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grab DJ, Lanners HN, Williams WL, Bucala R. Peripheral blood fibrocytes with foamy virus infection-like morphology. Hum. Pathol. 1999;30:1395–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang L, Scott PG, Dodd C, Medina A, Jiao H, Shankowsky HA, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. Identification of fibrocytes in postburn hypertrophic scar. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pilling D, Akbar AN, Girdlestone J, Orteu CH, Borthwick NJ, Amft N, Scheel-Toellner D, Buckley CD, Salmon M. Interferon-β mediates stromal cell rescue of T cells from apoptosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:1041–1050. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<1041::AID-IMMU1041>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scheel-Toellner D, Pilling D, Akbar AN, Hardie D, Lombardi G, Salmon M, Lord JM. Inhibition of T cell apoptosis by IFN-β rapidly reverses nuclear translocation of protein kinase C-δ. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2603–2612. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2603::AID-IMMU2603>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Buckley CD, Amft N, Bradfield PF, Pilling D, Ross E, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Amara A, Curnow SJ, Lord JM, Scheel-Toellner D, Salmon M. Persistent induction of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by TGF-β1 on synovial T cells contributes to their accumulation within the rheumatoid synovium. J. Immunol. 2000;165:3423–3429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buckley CD. Why do leucocytes accumulate within chronically inflamed joints? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1433–1444. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]