Abstract

Background

The Routine Universal Screening for HIV (RUSH) program provides opt-out HIV testing and linkage to care for emergency department (ED) patients in Harris Health System, Houston, TX. Seventy-five percent of patients testing positive in this program have been previously diagnosed. Whether linkage to care is increased among these patients is unknown.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of persons tested for HIV in the ED between 2008–2012 but had a previously documented positive HIV test ≥1 year prior. Outcomes were engagement in care (≥1 HIV outpatient visits in 6 months), retention in care (≥2 HIV outpatient visits in 12 months, at least 3 months apart) and virologic suppression (<200 c/ml in 12 months) compared before and after the ED visit. Analysis was conducted using McNemar’s test and multivariate conditional logistic regression.

Results

A total of 202,767 HIV tests identified 2068 previously diagnosed patients. The mean age was 43 years with 65% male and 87% racial and ethnic minorities. Engagement in care increased from 41.3% pre-visit to 58.8% post-visit (P<0.001). Retention in care increased from 32.6% pre-visit to 47.1% post-visit (P<0.001). Virologic suppression increased from 22.8% pre-visit to 34.0% post-visit (P<0.001). Analyses revealed that engagement in care after visit improved most among younger participants (ages 16 to 24), retention improved across all groups, and virologic suppression improved most among participants 25 to 34 years old.

Conclusions

Routine opt-out HIV testing in an ED paired with standardized service linkage improves engagement, retention, and virologic suppression in previously diagnosed patients.

Keywords: HIV testing, HIV linkage to care, retention in care, engagement in care, viral suppression, previously diagnosed

Introduction

Routine opt-out HIV testing programs in emergency departments (EDs) efficiently and acceptably increase the number of patients undergoing HIV testing.1–3 Although rapid HIV testing platforms have been used in most EDs4–10 that have implemented routine testing, non-rapid technology provides an effective and low-cost strategy for testing large volumes of patients.11 Large volume HIV testing in EDs helps identify a portion of the 14%12 of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States who are as yet unaware of their diagnosis.13 Awareness of their HIV infection subsequently limits the spread of HIV infection, as most people reduce risky behaviors once aware of their status.14 More importantly, earlier diagnosis and treatment generally yields improved clinical outcomes for the infected person and viral load suppression reduces the risk of transmission to sexual partners.15–18 When conducted in health care settings, HIV testing may also facilitate linkage to care among patients already aware of their diagnosis.

In the United States, 20% of people who are aware that they are HIV-infected have not been linked to care. Even among those successfully linked to care, only about half are retained in care.12 Identifying HIV-infected persons who are not linked to care or are poorly retained in care is not easy.19–21 The Routine Universal Screening for HIV program (RUSH) provides opt-out HIV testing and linkage to care for emergency department (ED) patients in Harris Health System, the largest publically funded health system in the state of Texas.11 We hypothesize that previously diagnosed patients could benefit from repeated screening by our HIV screening program to facilitate linkage or re-linkage to HIV care. We aimed to determine if, when accompanied by robust linkage to care efforts, large scale HIV testing benefit these previously diagnosed patients.

Methods

The RUSH Program

Harris Health System provides publically funded healthcare for uninsured and underinsured patients in Harris County. Most patients served (64%) have no other source of health care coverage. Following the 2006 CDC recommendations for routine opt-out HIV testing in healthcare settings,22 Harris Health System established the Routine Universal Screening for HIV (RUSH) program. The program was designed to automatically add an HIV screening test for any patient 16 years of age or older, having an IV inserted or having blood drawn for other reasons, unless the patient opted-out. Initially launched in the Ben Taub General Hospital (BTGH) ED in 2008, the program was later expanded to include the Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) General Hospital ED in 2009. These EDs are two of the busiest EDs in the region, with more than 170,000 patient visits each year between them.23 The majority of patients are racial and ethnic minorities (57% Hispanic and 26% Black), populations which historically have had less access to care, and poorer rates of care engagement, retention and viral suppression.12 The RUSH testing program now also includes 13 community health centers, Quentin Mease Community Hospital, 10 homeless shelter clinics, and one mobile unit, performing more than 100,000 HIV tests annually with an overall positivity rate of 1.8%. In 2013, more than 55,000 tests were conducted in the two EDs, with a 1.5% positivity rate.

Within Harris Health System, outpatient HIV care is primarily provided at the Thomas Street Health Center, the oldest free-standing HIV clinic in the United States. Two satellite sites, Northwest Clinic and Settegast Clinic, provide evening hours and also provide HIV specialty care intercalated with general medical care. Together, these three Ryan White funded clinics are the largest collective provider of outpatient HIV care in the Houston area, providing care for more than 5500 of the approximately 22,000 HIV-infected people in the region in 2011.24 However, not all patients who receive services in the BTGH and LBJ EDs receive ambulatory HIV care within Harris Health, since other HIV primary care clinics not affiliated with Harris Health System also receive Ryan White funding and patients with insurance may elect to receive outpatient care elsewhere. These factors limit access to data for some patients for both clinical and research purposes.

Service Linkage Workers (SLW) are an integral component of the RUSH program. They provide non-medical case management services, HIV counseling and facilitation of linkage to HIV care for patients newly diagnosed with HIV as well as previously diagnosed patients who may be out of care. With offices in both hospital EDs, SLWs work closely with physicians to deliver HIV test results to patients and to provide linkage to medical and social services. SLWs attempt contact with all patients who test positive for HIV. If the test is performed on evenings or weekends contact is attempted on the next business day. Linkage services are tailored to the patient’s needs but most often includes post-test counseling, assistance with transportation, completion of Harris Health and Ryan White eligibility determination processes, AIDS Drug Assistance Program applications, and scheduling of appointments.

SLWs retain a patient in their caseload until the patient is linked or re-linked to care. After completion of an outpatient visit with a provider with antiretroviral prescribing privileges, a patient is considered (re)-linked to care and the patient is transferred to a SLW based at the Thomas Street Health Center or the satellite HIV clinic. If a patient does not attend HIV medical appointments after completing the first appointment, the health care provider’s nursing staff contacts the patient to reschedule follow-up. SLWs based at Thomas Street Health Center or the satellite clinics assist with patient retention efforts and address any new needs that emerge.

Data Sources and Analysis

HIV test results and medical records from the RUSH testing program at BTGH and LBJ between 2009 and 2012 were evaluated. Test records and results were extracted from electronic laboratory databases. As a routine part of the RUSH program, all positive HIV test results from Harris Health facilities are sent to the City of Houston Department of Health and Human Services where they are compared against local and state surveillance databases to identify previously diagnosed cases. Patient demographics and clinical visit data at Harris Health were extracted from the electronic medical records (EMR). Data from other Ryan White providers in the Houston Eligible Metropolitan Area were extracted from the Centralized Patient Care Data Management System (CPCDMS), which contains data on visits provided by all Ryan White funded clinics in the area. The CPCDMS database only provides limited information about the date and location of visits and does not include data on patient visits not funded by Ryan White. In contrast, Harris Health databases include all patients regardless of payor status and provide detailed information about the visits and laboratory test results.

Our study cohort included persons previously diagnosed with HIV infection who had an ED visit at BTGH or LBJ between 2009 and 2012 and a positive HIV test result at the visit. We restricted the cohort to persons with an original date of diagnosis that was at least one year prior to the ED visit date in order to limit confounding from more recently diagnosed patients who are less likely to have been on medication long enough to achieve virologic suppression and who may have not yet had opportunity to achieve engagement or retention in care. If the patient had more than one qualifying visit, analysis included only the first visit. Thus the “index visit” was the first ED visit between 2009 and 2012 with an HIV positive test result that occurred at least one year after the person’s date of HIV diagnosis.

We then compared outcomes of interest in the time period just before the visit to outcomes just after the index visit. Outcomes of interest included engagement in care, retention in care, and viral suppression. Engagement in care reflected short-term retention, which we defined as having completed an HIV primary care visit in a 6-month period. Because we are not studying the time period after diagnosis, we did not term our short-term retention outcome ‘linkage’ and instead use the phrase “engagement.” We selected a 6-month interval for engagement because we considered a 3-month interval too restrictive for the pre-visit interval. For retention in care, we used the HRSA definition of having completed two HIV primary care visits in a 12-month period, with the two visits being at least 3 months apart.25 Viral suppression was defined as having an HIV viral load (VL) below 200 copies/ml at any point in a 12-month period. For engagement and retention in care, the 6- and 12-month intervals immediately pre-visit were compared to those intervals immediately post-visit. In order to correctly attribute VL outcomes to the appropriate timeframe, the pre-visit period for VL was extended until 10 days after the index visit, because a viral load drawn within a few days of the ED visit likely reflects care provided before the ED visit. The post-visit period for VL was similarly extended, and therefore went from 11 days after the index visit until 12 months and 10 days after. HIV viral load results were only available for patients who underwent viral load testing within Harris Health System. Our primary analyses considered persons with no viral load results during the time period of interest as failures.

In order to develop a comparison group, we identified patients in the RUSH cohort who had had an ED visit during a four year period prior to the RUSH era, and whose follow-up after that visit would not extend into the RUSH era (e.g., visits from 2004 to 2007). We also required that they had been initially diagnosed with HIV greater than one year prior to that pre-RUSH era visit. If multiple qualifying ED visits existed for a patient, the ED visit most proximate to the RUSH-era index visit was used for analysis. During the pre-RUSH period, there was no policy on HIV testing, and tests were ordered for an individual patient at the discretion of the treating provider. There also were no SLWs embedded in the ED, and all linkage to outpatient HIV care was via passive referral, including providing phone numbers and recommending that patients seek outpatient HIV care. We then measured our outcomes of interest before and after the pre-RUSH era ED visit. We compared pre/post changes in these outcomes during this control period to pre/post changes during the RUSH time period using conditional logistic regression with a main effect of ED visit, a main effect of period (RUSH era vs pre-RUSH era), and an interaction term to test whether the effect of the ED visit on outcomes differed between the two periods.

Paired observations (pre-visit and post-visit) were constructed for each patient in the cohort. Proportions of patients engaged in care, retained in care, and virally suppressed before and after the index visit were compared using McNemar’s test. For purposes of analyses, racial and ethnic groups were categorized as White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic and other. To test for significance of the change within demographic subgroups of the cohorts, defined by sex, race, age, year of visit, and years since original diagnosis, we used conditional logistic regression with an interaction term containing the demographic characteristic and time (pre- or post-visit).26

All data analysis was conducted using SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and STATA 12 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Between 2009 and 2012, there were 202,767 HIV tests performed at BTGH and LBJ emergency departments. Of those tests, 3613 (1.8%) were confirmed positive, with 655 being new diagnoses and 2958 positive test results among 2188 previously diagnosed individuals. Among the 2,188 previously diagnosed patients, 2687 (90.8%) positive test results were obtained from patients who were diagnosed at least one year prior to the index visit. Restricting these results to the first positive test from an ED visit that occurred at least a year after first diagnosis yielded 2068 unique patients in our study cohort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of a cohort of 2068 patients previously diagnosed with HIV infection who had a RUSH-era ED visit (study period cohort) and the subset who also had a pre-RUSH-era ED visit (control period cohort subset)

| Study Period Cohort (N=2068) | Control Period Cohort Subset (N=672) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Sex | Female | 729 | 35% | 276 | 41% |

| Male | 1339 | 65% | 396 | 59% | |

|

| |||||

| Race/ethnicity | Black non-Hispanic | 1403 | 68% | 522 | 78% |

| Hispanic | 354 | 17% | 85 | 13% | |

| White non-Hispanic | 276 | 13% | 63 | 9% | |

| Other | 35 | 2% | 2 | 0% | |

|

| |||||

| Year of visit | 2009 (2004 for Control) | 600 | 29% | 58 | 9% |

| 2010 (2005 for Control) | 602 | 29% | 107 | 16% | |

| 2011 (2006 for Control) | 440 | 21% | 140 | 21% | |

| 2012 (2007 for Control) | 426 | 21% | 367 | 54% | |

|

| |||||

| Age group | 16–24 | 86 | 4% | 31 | 5% |

| 25–34 | 401 | 19% | 137 | 20% | |

| 35–44 | 661 | 32% | 261 | 39% | |

| 45–54 | 656 | 32% | 190 | 28% | |

| 55+ | 264 | 13% | 53 | 8% | |

|

| |||||

| Years since diagnosis | 1–5 | 627 | 30% | 186 | 28% |

| 6–10 | 516 | 25% | 221 | 33% | |

| 11–15 | 484 | 23% | 165 | 25% | |

| 16–20 | 274 | 13% | 76 | 11% | |

| 21+ | 167 | 13% | 24 | 4% | |

|

| |||||

| Total | 2068 | 100% | 672 | 100% | |

Of the 2068 previously diagnosed patients, 65% were male and the majority were racial and ethnic minorities with 68% Black, 17% Hispanic, and only 13% White non-Hispanic. Mean age was 43 ± 10 years (Table 1). The median number of years since diagnosis was 9, with the majority of patients (63%) having been diagnosed between 1 and 10 years prior. The comparison group included 672 of the 2068 patients in the study cohort that had a qualifying ED visit in the 2004 to 2007 control era. The demographics of the comparison cohort, which is a subset of the study cohort, are similar to that of the study cohort (Table 1).

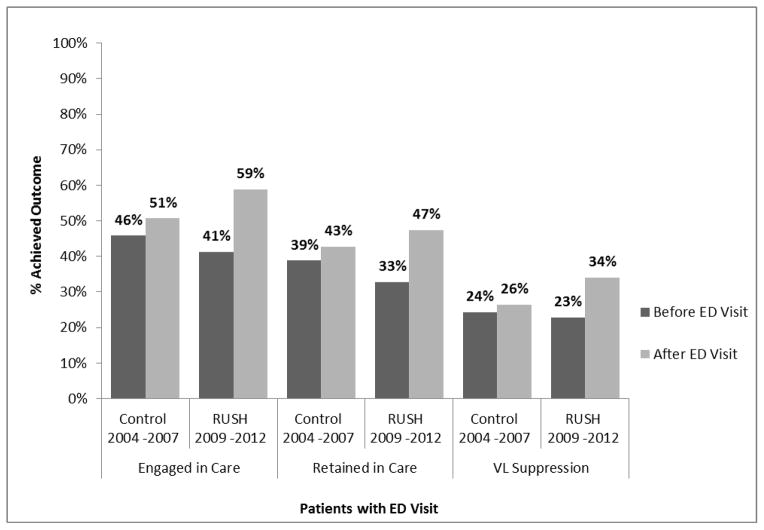

The percentage of patients engaged in care (at least one HIV primary care visit in 6 months) increased from 41.3% pre-visit to 58.8% post-visit (P<0.001; Table 2). The increase was most pronounced among younger participants (ages 16 to 24 years), with a change in the percentage of patients engaged in care from 27% pre-visit to 56% post-visit (p<0.001). There was no substantial difference in the increase in engagement in care by sex, race/ethnicity, year of the visit, or years since diagnosis with all groups experiencing an improvement except for the small group of patients who were of “other” race/ethnicity (not Black, Hispanic, or White). Interaction analyses confirmed these results (Table 2). During the four-year time period before the RUSH era, there was a statistically significant improvement in the proportion of patients engaged in care before and after a given ED visit (p=0.017; Figure 1). However, conditional regression reveals the magnitude of the improvement in care engagement during the RUSH era was greater (p<0.001) than in the pre-RUSH era.

Table 2.

Engagement in care before and after a RUSH-era ED visit among a cohort of 2068 patients previously diagnosed with HIV infection

| n | Engagement in Care | McNemar OR Effectiveness of intervention (95% CI) | P-value | χ2 test Difference of effectiveness across groups | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |||||||||

| # | % | # | % | |||||||

| Sex | Female | 729 | 304 | 42% | 438 | 60% | 4.72 (3.30–6.77) | <0.001 | 2.40 | 0.122 |

| Male | 1339 | 550 | 41% | 778 | 58% | 3.38 (2.69–4.24) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Race | Black | 1403 | 521 | 37% | 804 | 57% | 4.41 (3.47–5.60) | <0.001 | 7.56 | 0.0561 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 354 | 208 | 59% | 257 | 73% | 2.88 (1.85–4.51) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| White | 276 | 115 | 42% | 141 | 51% | 2.18 (1.32–3.61) | 0.002 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Other | 35 | 10 | 29% | 14 | 40% | 5.00 (0.58–42.8) | 0.142 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age group | 16–24 | 86 | 23 | 27% | 48 | 56% | 9.33 (2.84–30.7) | <0.001 | 13.24 | 0.0102 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 25–34 | 401 | 137 | 34% | 236 | 59% | 5.95 (3.70–9.55) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 35–44 | 661 | 268 | 41% | 377 | 57% | 3.53 (2.52–4.96) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 45–54 | 656 | 300 | 46% | 409 | 62% | 3.53 (2.52–4.96) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 55+ | 264 | 126 | 48% | 146 | 55% | 1.87 (1.13–3.10) | 0.015 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Year of visit | 2009 | 600 | 273 | 46% | 353 | 59% | 2.86 (2.02–4.05) | <0.001 | 5.03 | 0.1693 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 2010 | 602 | 246 | 41% | 340 | 56% | 3.41 (2.39–4.87) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2011 | 440 | 174 | 40% | 269 | 61% | 4.52 (2.98–6.86) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2012 | 426 | 161 | 38% | 254 | 60% | 5.04 (3.22–7.89) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | 1–5 | 627 | 232 | 37% | 366 | 58% | 5.19 (3.55–7.57) | <0.001 | 5.44 | 0.2448 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 6–10 | 516 | 221 | 43% | 318 | 62% | 3.77 (2.60–5.47) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 11–15 | 484 | 196 | 41% | 275 | 57% | 3.19 (2.20–4.64) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 16–20 | 274 | 139 | 51% | 167 | 61% | 2.65 (1.52–4.62) | 0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 21+ | 167 | 66 | 40% | 90 | 54% | 3.00 (1.56–5.77) | 0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Total | 2068 | 854 | 41% | 1216 | 59% | 3.74 (3.09–4.53) | <0.001 | ||

Figure 1.

Outcomes among a cohort of patients previously diagnosed with HIV infection, before and after a RUSH-era ED visit (2009–2012; N= 2068), and before and after a pre-RUSH era ED visit (2004–2007; N= 672)

Retention in care (two visits separated by at least 90 days in a 12-month period) increased from 32.6% pre-visit to 47.1% post-visit (P<0.001; Table 3). There were marked changes among younger patients, with increases from 15% to 37% for patients 16 to 24 years old, and from 24% to 45% among patients between 25 and 34 years old. The only age group that did not demonstrate a significant change in the proportion retained in care was comprised of participants over the age of 55 years. There was also no change among the 29 people who were neither White, Black, nor Hispanic; however the small sample size limits our ability to assess the importance of these data. Comparing improvements within demographic subsets, we found significant differences in age, with greater improvement in retention in care among younger subjects compared with older subjects, and with years since diagnosis, with greater improvements in retention with persons diagnosed <16 years before the visit. Comparing the pre-RUSH era with the RUSH era, we found that the ED visit was significantly more likely to improve retention in care in the RUSH era (p<0.001; Figure 1).

Table 3.

Retention in care before and after a RUSH-era ED visit among a cohort of 2068 patients previously diagnosed with HIV infection

| n | Retention in Care | McNemar OR Effectiveness of intervention (95% CI) | P-value | χ2 test Difference of effectiveness across groups | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |||||||||

| # | % | # | % | |||||||

| Sex | Female | 729 | 245 | 34% | 356 | 49% | 3.52 (2.52–4.92) | <0.001 | 2.99 | 0.083 |

| Male | 1339 | 434 | 32% | 623 | 47% | 2.49 (2.03–3.06) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Race | Black | 1403 | 413 | 29% | 644 | 46% | 3.18 (2.55–3.95) | <0.001 | 6.39 | 0.0940 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 354 | 167 | 47% | 212 | 60% | 2.36 (1.57–3.55) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| White | 276 | 89 | 33% | 112 | 41% | 1.74 (1.12–2.70) | 0.014 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Other | 35 | 10 | 29% | 11 | 31% | 2.00 (0.18–22.1) | 0.571 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age group | 16–24 | 86 | 13 | 15% | 32 | 37% | 4.80 (1.83–12.6) | 0.001 | 20.17 | 0.0005 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 25–34 | 401 | 97 | 24% | 180 | 45% | 4.19 (2.73–6.43) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 35–44 | 661 | 207 | 31% | 318 | 48% | 3.41 (2.46–4.74) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 45–54 | 656 | 253 | 38% | 334 | 51% | 2.31 (1.71–3.11) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 55+ | 264 | 109 | 41% | 115 | 44% | 1.19 (0.74–1.90) | 0.474 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Year of visit | 2009 | 600 | 209 | 35% | 297 | 50% | 2.62 (1.92–3.60) | <0.001 | 0.36 | 0.9485 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 2010 | 602 | 200 | 33% | 281 | 47% | 2.76 (1.97–3.87) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2011 | 440 | 138 | 31% | 211 | 48% | 3.03 (2.08–4.41) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2012 | 426 | 132 | 31% | 190 | 45% | 2.66 (1.80–3.92) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | 1–5 | 627 | 185 | 30% | 301 | 48% | 3.90 (2.76–5.52) | <0.001 | 14.58 | 0.0057 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 6–10 | 516 | 172 | 33% | 257 | 50% | 2.81 (2.01–3.92) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 11–15 | 484 | 153 | 32% | 225 | 46% | 3.12 (2.12–4.59) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 16–20 | 274 | 114 | 42% | 130 | 47% | 1.47 (0.95–2.27) | 0.083 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 21+ | 167 | 55 | 33% | 66 | 40% | 1.69 (0.91–3.13) | 0.097 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Total | 2068 | 679 | 33% | 979 | 47% | 2.75 (2.31–3.28) | <0.001 | ||

Viral load results were available for 1220 patients (59%) in the year pre-index visit and 1166 patients (56%) in the year post-index visit. Virologic suppression to less than 200 copies/ml increased from 22.8% pre-visit to 34.0% post-visit when considering missing data as failure (P<0.001; Table 4). There was no difference in relative effectiveness by sex: rates of virologic suppression in men improved from 21% to 33% (p< 0.001) and rates in women improved from 26% to 36% (p< 0.001), with no significant difference in those improvements by sex (P=0.685). Likewise there was no significant difference in effectiveness between racial and ethnic groups (P=0.46). Rates improved in Black people from 22% to 34% (p< 0.001), in Hispanic people from 28% to 41% (p< 0.001), and in White people from 21% to 29% (p=0.015). Improvements in virologic suppression were most significant among participants 25 to 34 years old. Only 9% of previously diagnosed patients in this age group demonstrated virologic suppression in the pre-visit timeframe and 28% demonstrated virologic suppression by 12 months post-visit (p<0.001). Calendar year of visit was also an important factor in virologic suppression. Each ensuing year both the pre-visit rates and post-visit rates of VS improved, but the magnitude of the change in virologic suppression due to the ER visit did not vary by year (Table 4). The RUSH-era ED visit had little effect on virologic suppression in persons diagnosed at least 16 years before the visit, but it did improve suppression in persons more recently diagnosed. Improvements in VL suppression were significantly higher in the RUSH era compared to the pre-RUSH era (P<0.001; Figure 1).

Table 4.

Virologic suppression before and after a RUSH-era ED visit among a cohort of 2068 patients previously diagnosed with HIV infection

| n | Virologic Suppression | McNemar OR Effectiveness of intervention (95% CI) | P-value | χ2 test Difference of effectiveness across groups | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |||||||||

| # | % | # | % | |||||||

| Sex | Female | 729 | 187 | 26% | 265 | 36% | 2.47 (1.80–3.40) | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.685 |

| Male | 1339 | 285 | 21% | 439 | 33% | 2.68 (2.11–3.41) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Race | Black | 1403 | 310 | 22% | 475 | 34% | 2.76 (2.18–3.49) | <0.001 | 2.59 | 0.4600 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 354 | 98 | 28% | 144 | 41% | 2.84 (1.80–4.48) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| White | 276 | 59 | 21% | 80 | 29% | 1.81 (1.12–2.92) | 0.015 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Other | 35 | 4 | 11% | 5 | 14% | ∞* | - | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age group | 16–24 | 86 | 7 | 8% | 13 | 15% | 2.20 (0.76–6.33) | 0.144 | 23.73 | 0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 25–34 | 401 | 37 | 9% | 113 | 28% | 6.84 (3.83–12.3) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 35–44 | 661 | 134 | 20% | 204 | 31% | 2.49 (1.77–3.49) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 45–54 | 656 | 189 | 29% | 268 | 41% | 2.65 (1.90–3.69) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 55+ | 264 | 104 | 39% | 106 | 40% | 1.06 (0.66–1.72) | 0.806 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Year of visit | 2009 | 600 | 123 | 21% | 187 | 31% | 2.73 (1.87–3.98) | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.9730 |

| 2010 | 602 | 131 | 22% | 194 | 32% | 2.47 (1.73–3.51) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2011 | 440 | 105 | 24% | 167 | 38% | 2.72 (1.86–3.99) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2012 | 426 | 112 | 26% | 156 | 37% | 2.52 (1.64–3.87) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | 1–5 | 627 | 106 | 17% | 200 | 32% | 4.24 (2.83–6.36) | <0.001 | 28.12 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 6–10 | 516 | 117 | 23% | 189 | 37% | 3.00 (2.06–4.37) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 11–15 | 484 | 101 | 21% | 164 | 34% | 3.25 (2.13–4.96) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 16–20 | 274 | 97 | 35% | 98 | 36% | 1.03 (0.63–1.68) | 0.901 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 21+ | 167 | 50 | 30% | 53 | 32% | 1.15 (0.63–2.09) | 0.648 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Total | 2068 | 471 | 23% | 704 | 34% | 2.61 (2.15–3.16) | <0.001 | ||

This value is undefined since the number of individuals with race “other” who were virologically suppressed before the ED visit who were not suppressed afterward was 0, and this 0 is the denominator of this odds ratio.

Discussion

Routine opt-out HIV testing programs paired with service linkage address two major challenges of the US HIV epidemic: identifying undiagnosed individuals and facilitating engagement and retention in care.26 While these benefits are obvious for newly diagnosed patients, we found benefit from these strategies for previously diagnosed patients not engaged in care but tested in the context of an ED visit. It is worth noting that our results likely represent a lower bound estimate since we only had access to visit and laboratory data from our own healthcare system and visit data from patients receiving care at Ryan White funded organizations in the Houston area. Approximately 10% of patients who test HIV-positive in the RUSH program are linked to care outside of Harris Health System.27 Among 1739 HIV-positive patients admitted to BTGH over a 3-year period, approximately 20% reported using outpatient services outside of Harris Health System (T. P. Giordano, MD, unpublished data, November 2014). This study demonstrates improvements in engagement, retention, and virologic suppression after patients previously diagnosed with HIV had an HIV test in an ED with a routine testing program and embedded service linkage workers tasked with linking and relinking all positive patients to HIV primary care.

We designed the RUSH program to streamline the HIV testing process in the ED. As a result, some patients who may have been previously diagnosed with HIV infection are tested again. Some patients diagnosed outside our system do not disclose their status to the ED providers. In the RUSH program, routine testing generally occurs at triage, before the ED physician has an opportunity to manually check for prior HIV tests results. One could program the electronic medical record to automatically review testing history and cancel testing on persons known positive or very recently tested. However, our data show that the portion of tests performed on patients who had previously tested positive in our EDs is negligible (0.39% of all tests). Furthermore as we have demonstrated here, benefits exist for many previously diagnosed patients who undergo repeat testing.

The demographics of the patients testing HIV-positive in the RUSH program differ from the general epidemic in Houston. In the Houston area, men predominate in the HIV epidemic, comprising 73.7% of cases,24 whereas 65% of the previously diagnosed patients in the RUSH program were men. This may reflect increased utilization of health care services by women. National data sources reveal that more ED visits are made by women (between 53.9% and 55.8%) than men (between 44.2% and 46.1%).28

In the Houston area, 78.1% of those newly diagnosed with HIV infection are linked to care within three months of diagnosis. Adult risk groups with the highest rates of HIV such as Black people, MSM and young adults also have the poorest linkage rates, 74.5%, 75.4% and 68% respectively.24 Despite the existing disparities, these linkage rates are better than those in the general US epidemic. Our engagement in care outcome delineates more proximate care involvement, within the 6 months surrounding the re-test date. Engagement also includes people who were previously diagnosed, yet were unengaged, an arguably more challenging group to influence. It is notable that regardless of number of years since diagnosis, there was an improvement in engagement in care. There are no comparable data on re-linkage from ED-based testing programs. In the ARTAS study, conducted primarily among newly diagnosed patients, a case management intervention improved the percent of patients with an HIV primary care visit within 6 months of diagnosis from 49% to 64%.29 The RUSH program yielded marked improvement in engagement in care, from 41% to 59%, a significantly higher rate of improvement than during the pre-RUSH era, where the improvement in engagement was from 46% to 51%. The substantial improvement in care engagement among the youngest age groups is notable.

Post-program implementation, 47.1% of HIV infected patients were retained in care, significantly higher than the 39 to 43% retained in care during the pre-RUSH era and comparable to the 50.9% national retention in care rate.30 Likewise the 33.4% rate of virologic suppression was also comparable to the national rate of 37.3%.30 The patients in this study, though not necessarily engaged in regular HIV primary care, demonstrated health care access in that they were presenting to an emergency department.

Virologic suppression, the only documented outcome with differences by program year, may have been influenced by changes in treatment guidelines and practice patterns that lowered the CD4 threshold for treatment initiation and the availability of new antiretroviral options.31,32 Persons who were diagnosed with HIV infection for >15 years did not show improvements in retention in care and virologic suppression after their ED visit, partly because they tended to go into the visit with higher rates of success than more recently diagnosed patients. An individual patient’s success or failure in dealing with HIV infection is probably very well established by that point, such that an ED visit has little impact on subsequent HIV outcomes.

Each ED in the RUSH program was staffed by a single service linkage worker who was available during business hours on weekdays for immediate care engagement facilitation. A list of positive HIV tests performed off-hours was provided to the SLWs for follow-up by phone during the following business day; however, contact was not always successfully made. Expansion of staff coverage for off-hours could extend the benefit of this program by enabling contact with patients while they are still in the ED.

EDs in which the administrative leadership has concerns about HIV screening costs are less likely to adopt routine HIV screening programs.33 Expanding HIV testing is highly cost effective and may be cost saving, given that early diagnosis can reduce forward transmission, and the estimated lifetime cost of caring for a person with HIV infection is over $350,000.34 Future research could explore the cost impact of such a program taking into consideration benefits to both newly and previously diagnosed patients as well as the costs of repeat testing. A preliminary analysis of our data shows a clear benefit for repeat testing, as 10% of our newly diagnosed patients had tested negative within our program and later sero-converted (unpublished data).

Study limitations include the absence of data on engagement or retention for patients receiving care in non-Ryan White funded agencies outside of Harris Health System. Between 10 and 20% of HIV infected patients who use these EDs receive care outside of Harris Health System.27 Similarly, only viral load data from Harris Health was accessible for this study. It is difficult to estimate the magnitude of the effect of this limitation, but it will bias our estimates of all the outcomes downward because missing outcome data were counted as failures. However, missing data in the pre-visit timeframe could have possibly inflated the extent of changes observed if an ED visit coincided with a change in provider to any Ryan White provider (engagement and/or retention impact) or Harris Health (viral load suppression impact). Further, the observational nature of this data and the use of historical controls preclude strong statements about causation. While there were no wait lists or major changes to the Texas AIDS Drug Assistance Program or the major providers receiving Ryan White funding during the years of this study, there are temporal biases which might affect our data, such as changes in treatment guidelines and a growing awareness of the importance of retention in care. The control group contained patients who had at least one ED visit in the designated 4 year time frame prior to the RUSH era. The observational nature of the data limits our ability to make more than general comments on how outcomes in the control group differed from outcomes during the RUSH period.

Offering routine opt-out non-rapid HIV testing in busy emergency departments can identify a high-risk group of people who were previously diagnosed but are out of care. Our findings demonstrate significant improvements in care engagement, retention in care and virologic suppression among previously diagnosed patients who were retested though our program. Providing routine HIV testing in a setting where staff are available to link patients to outpatient HIV primary care services can successfully facilitate linkage or re-linkage for patients who are currently not in care.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a supplement to the National Institutes of Health-funded Baylor College of Medicine-University of Texas Houston Center for AIDS Research (Grant Number P30AI036211), supplemental funds to the District of Columbia Developmental Center for AIDS Research (Grant Number 5P30AI087714), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant Number 5U62PS000775-03), the facilities and resources of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the facilities and resources of Harris Health System. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, Harris Health System nor the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors would also like to acknowledge: Ken Malone, HIV Project Analyst and Coordinator of Routine Testing who played a major role in launching the RUSH program; Nicholas Sloop, the CDC Public Health Advisor at the Houston Department of Health and Human Services whose database support was crucial to the success of the RUSH program, and research coordinators Sophie Minick and Carmen Avalos, MD, for their assistance in preparing the manuscript for publication.

Sources of Funding: This study was supported by a supplement to the National Institutes of Health-funded Baylor College of Medicine-University of Texas Houston Center for AIDS Research (Grant Number P30AI036211), supplemental funds to the District of Columbia Developmental Center for AIDS Research (Grant Number 5P30AI087714), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant Number 5U62PS000775-03), the facilities and resources of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the facilities and resources of Harris Health System.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No relevant conflicts of interest were declared by any of the authors.

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented: none

Contributor Information

Charlene A. Flash, Email: charlene.flash@bcm.edu, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Siavash Pasalar, Email: siavash.pasalar@harrishealth.org, Harris Health System, Houston, TX.

Vagish Hemmige, Email: vagish.hemmige@bcm.edu, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Jessica A. Davila, Email: jdavila@bcm.edu, Baylor College of Medicine and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Houston, TX.

Camden J. Hallmark, Email: Camden.Hallmark@houstontx.gov, Houston Department of Health and Human Services, Houston, TX.

Marlene McNeese, Email: marlene.mcneese@houstontx.gov, Houston Department of Health and Human Services, Houston, TX.

Nancy Miertschin, Email: nancy.miertschin@harrishealth.org, MPH Harris Health System, Houston, TX.

Michael C. Ruggerio, Email: michael.ruggerio@harrishealth.org, Harris Health System, Houston, TX.

Thomas P. Giordano, Email: tpg@bcm.edu, Baylor College of Medicine and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Houston, TX.

References

- 1.Rayment M, Rae C, Ghooloo F, et al. Routine HIV testing in the emergency department: tough lessons in sustainability. HIV Med. 2013 Oct;14 (Suppl 3):6–9. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, et al. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines: results from a high-prevalence area. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Dec 1;46(4):395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan DJ, Cowan E, Fitzpatrick L, et al. Legislated human immunodeficiency virus testing in New York State Emergency Departments: reported experience from Emergency Department providers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014 Feb;28(2):91–97. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knapp H, Hagedorn H, Anaya HD. HIV rapid testing in a Veterans Affairs hospital ED setting: a 5-year sustainability evaluation. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Aug;32(8):878–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain S, Lowman ES, Kessler A, et al. Seroprevalence study using oral rapid HIV testing in a large urban emergency department. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2012 Nov;43(5):e269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coeller N, Kuo I, Brown J. Nontargeted rapid human immunodeficiency virus screening provided by dedicated personnel does not adversely affect emergency department length of stay. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011 Jul;18(7):708–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Byyny RL, et al. Design and implementation of a controlled clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of routine opt-out rapid human immunodeficiency virus screening in the emergency department. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009 Aug;16(8):800–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman AE, Sattin RW, Miller KM, Dias JK, Wilde JA. Acceptance of rapid HIV screening in a southeastern emergency department. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009 Nov;16(11):1156–1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderon Y, Leider J, Hailpern S, et al. High-volume rapid HIV testing in an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009 Sep;23(9):749–755. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid HIV testing in emergency departments--three U.S. sites, January 2005-March 2006. MMWR. 2007;56(24):597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoxhaj S, Davila JA, Modi P, et al. Using nonrapid HIV technology for routine, opt-out HIV screening in a high-volume urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Jul;58(1 Suppl 1):S79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital Signs: HIV Diagnosis, Care, and Treatment Among Persons Living with HIV - United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Nov 28;63(47):1113–1117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. Jama. 2010 Jul 21;304(3):284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Aug 1;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogg RS, Yip B, Chan KJ, et al. Rates of disease progression by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load after initiating triple-drug therapy. JAMA. 2001 Nov 28;286(20):2568–2577. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zolopa A, Andersen J, Powderly W, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lodwick RK, Sabin CA, Porter K, et al. Death rates in HIV-positive antiretroviral-naive patients with CD4 count greater than 350 cells per microL in Europe and North America: a pooled cohort observational study. Lancet. 2010 Jul 31;376(9738):340–345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60932-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Udeagu CC, Webster TR, Bocour A, Michel P, Shepard CW. Lost or just not following up: public health effort to re-engage HIV-infected persons lost to follow-up into HIV medical care. Aids. 2013 Sep 10;27(14):2271–2279. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328362fdde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabral HJ, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, et al. Outreach program contacts: do they increase the likelihood of engagement and retention in HIV primary care for hard-to-reach patients? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21 (Suppl 1):S59–67. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rumptz MH, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, et al. Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21 (Suppl 1):S30–39. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. 2006;55(RR-14) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris Health System. [Accessed November 9, 2014];Harris Health Sytem: About US-Facts and Figures, 2014. 2014 https://www.harrishealth.org/en/about-us/who-we-are/pages/statistics.aspx.

- 24.The 2013 Joint Epidemiologic Profile Workgroup of the Ryan White Planning Council and HIV Prevention Community Planning Group. [Accessed October 20, 2014];HIV/AIDS in the Houston Area: The 2013 Houston Area Integrated Epidemiologic Profile for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Services Planning. 2014 http://www.houstontx.gov/health/HIV-STD/2013_Epi_Profile%20--APPROVED--05-09-13.pdf.

- 25.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Metlay JP, et al. Comparing different measures of retention in outpatient HIV care. Aids. 2012 Jun 1;26(9):1131–1139. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283528afa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, Thompson MA. The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: from cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Oct;57(8):1164–1171. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giordano TP, Hallmark C. Partnerships to increase success in the continuum of HIV care in Houston, TX. CFAR/APC Continuum of Care Meeting; Washington, DC. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owens PL, Barrett ML, Gibson TB, Andrews RM, Weinick RM, Mutter RL. Emergency department care in the United States: a profile of national data sources. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Aug;56(2):150–165. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. Aids. 2005 Mar 4;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2011. [Accessed November 10, 2014];HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013 (5) http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/2011_Monitoring_HIV_Indicators_HSSR_FINAL.pdf.

- 31.Hammer SM, Eron JJ, Jr, Reiss P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. Jama. 2008 Aug 6;300(5):555–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. [Accessed October 30, 2014];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2009 http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 33.Berg LJ, Delgado MK, Ginde AA, Montoy JC, Bendavid E, Camargo CA., Jr Characteristics of U.S. emergency departments that offer routine human immunodeficiency virus screening. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012 Aug;19(8):894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutchinson AB, Farnham PG, Duffy N, et al. Return on public health investment: CDC's Expanded HIV Testing Initiative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Mar 1;59(3):281–286. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823e5bee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]